Abstract

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to a public health crisis. Only limited data are available on the characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 in France.

Aims

To investigate the characteristics, cardiovascular complications and outcomes of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 in France.

Methods

The Critical COVID-19 France (CCF) study is a French nationwide study including all consecutive adults with a diagnosis of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-Cov-2) infection hospitalized in 24 centres between 26 February and 20 April 2020. Patients admitted directly to intensive care were excluded. Clinical, biological and imaging parameters were systematically collected at hospital admission. The primary outcome was in-hospital death.

Results

Of 2878 patients included (mean ± SD age 66.6 ± 17.0 years, 57.8% men), 360 (12.5%) died in the hospital setting, of which 7 (20.7%) were transferred to intensive care before death. The majority of patients had at least one (72.6%) or two (41.6%) cardiovascular risk factors, mostly hypertension (50.8%), obesity (30.3%), dyslipidaemia (28.0%) and diabetes (23.7%). In multivariable analysis, older age (hazard ratio [HR] 1.05, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.03 − 1.06; P < 0.001), male sex (HR 1.69, 95% CI 1.11 − 2.57; P = 0.01), diabetes (HR 1.72, 95% CI 1.12 − 2.63; P = 0.01), chronic kidney failure (HR 1.57, 95% CI 1.02 − 2.41; P = 0.04), elevated troponin (HR 1.66, 95% CI 1.11 − 2.49; P = 0.01), elevated B-type natriuretic peptide or N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (HR 1.69, 95% CI 1.0004 − 2.86; P = 0.049) and quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score ≥ 2 (HR 1.71, 95% CI 1.12 − 2.60; P = 0.01) were independently associated with in-hospital death.

Conclusions

In this large nationwide cohort of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 in France, cardiovascular comorbidities and risk factors were associated with a substantial morbi-mortality burden.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Characteristics, Death, Cardiovascular risk factors

Résumé

Contexte

La pandémie de coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) a engendré une crise majeure de santé publique. Seules des données limitées sont disponibles sur les caractéristiques et le pronostic des patients hospitalisés pour COVID-19 en France.

Objectifs

Étudier les caractéristiques, les complications cardiovasculaires et le pronostic des patients hospitalisés pour COVID-19 en France.

Méthodes

L’étude Critical COVID-19 France (CCF) est une étude nationale française incluant consécutivement tous les adultes hospitalisés pour avec une infection au coronavirus 2 (SARS- Cov-2) dans 24 centres entre le 26 février et le 20 avril 2020. Les patients admis directement en soins critiques étaient exclus. Les paramètres cliniques, biologiques et iconographiques ont été systématiquement recueillis à l’admission. Le critère de jugement primaire était le décès intra-hospitalier.

Résultats

Sur les 2878 patients inclus (âge moyen ± écart type : 66,6 ± 17,0 ans, 57,8% d’hommes), 360 (12,5 %) sont décédés en milieu hospitalier, dont 7 (20,7 %) ont été transférés en soins critiques avant le décès. La majorité des patients présentaient au moins un (72,6 %) ou deux (41,6 %) facteurs de risque cardiovasculaire, principalement une hypertension (50,8 %), une obésité (30,3 %), une dyslipidémie (28,0 %) ou un diabète (23,7 %). En analyse multivariée, l’âge avancé (hazard ratio [HR] 1,05, intervalle de confiance [IC] à 95 % 1,03–1,06; P < 0,001), le sexe masculin (HR 1,69, IC à 95 % 1,11–2,57; P = 0,01), le diabète (HR 1,72, IC à 95 % 1,12–2,63; P = 0,01), l’insuffisance rénale chronique (HR 1,57, IC à 95 % 1,02–2,41; P = 0,04), l’élévation de la troponine (HR 1. 66, IC 95 % 1,11–2,49; P = 0,01), ou l’élévation du peptide natriurétique de type B (BNP) ou N-terminal peptide natriurétique de type B (NT-pro-BNP, HR 1,69, IC 95% 1,0004–2,86; P = 0,049) et un score Score Séquentiel rapide de Défaillance d’Organe (qSOFA) ≥ 2 (HR 1,71, IC 95 % 1,12–2,60; P = 0,01) étaient indépendamment associés au décès intra-hospitalier.

Conclusions

Dans cette cohorte nationale de patients hospitalisés pour COVID-19 en France, les comorbidités et facteurs de risque cardiovasculaires étaient associés à une augmentation majeure de la morbi-mortalité intra-hospitalière.

Mots-clés: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Caractéristiques, Décès, Facteurs de risque cardiovasculaire

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has led to a public health crisis of unprecedented magnitude. Up to the end of October 2020, more than 43 million cases of COVID-19 have been reported worldwide, and almost 1.15 million people had died [1], [2]. France has not been spared, with more than 1 million cases [3], [4], [5].

The classic profile of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 has been described in case series from China [6], [7], [8], the United States [9], [10], [11], Italy [12], [13] and the United Kingdom [14]. Most of these patients were overweight men with cardiovascular comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes [11], [14], [15]. Although the overall picture of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 is similar worldwide, some discrepancies persist. Conflicting data exist on the mortality rate, the proportion of patients requiring transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU), and the burden of diabetes, overweight or smoking on clinical outcomes [16], [17], [18]. These data were also obtained from multiple case series from several regions around the world, with different healthcare systems [7], [11], [12], [14]. Furthermore, at the beginning of the pandemic, there were no recommendations for medical treatment, respiratory support, or continuation or discontinuation of chronic treatments, resulting in inevitable heterogeneity in both populations and medical care. To date, epidemiological data on patients with COVID-19 in France remain scarce.

The Critical COVID-19 France (CCF) study was therefore designed to collate data from patients hospitalized for COVID-19 in a network of 24 French centres. The aim was to provide an overview of the patients hospitalized for COVID-19 in France, with an emphasis on:

-

•

the burden of cardiovascular comorbidities and treatments;

-

•

the incidence and impact of cardiovascular complications associated with COVID-19;

-

•

the outcomes of patients hospitalized for severe COVID-19 (i.e. mortality rate, proportion and timing of transfer to ICU).

Here we present the methodology and baseline data for the CCF study.

Methods

Study design and population

CCF is a French nationwide observational study conducted in 24 centres (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04344327). Participation was offered to all types of institutions (academic hospitals, general hospitals, private clinics). The 24 participating centres comprised 14 academic hospitals, five general hospitals, three private not-for-profit clinics, and two private clinics (Table A.1). All consecutive adults admitted to hospital with a diagnosis of SARS-Cov-2 infection between 26 February and 20 April 2020 were included. According to World Health Organization criteria, SARS-Cov-2 infection was defined as a positive result on real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction of nasal and pharyngeal swabs or lower respiratory tract aspirates (confirmed case), or as typical imaging characteristics on chest computed tomography (CT) when laboratory testing results were inconclusive (probable case) [17]. Patients were recruited consecutively from emergency units or conventional hospital departments over a period of 8 weeks. As the aim of the study was to investigate patients hospitalized for COVID-19 in conventional hospital wards, those admitted direct to ICU were excluded.

The CCF study was declared to and authorized by the French data protection committee (Commission Nationale Informatique et Liberté, CNIL, authorization n°2207326v0), and was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The authors had full access to and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data. The study was supported and organized under the supervision of the French Society of Cardiology.

Data collection

All data were collected by local investigators and entered into an electronic case-report form via REDCap software (Research Electronic Data Capture, Vanderbilt University), hosted on a secure server from the French Institute of Health and Medical Research at the Paris Cardiovascular Research Centre. Patient baseline information included demographic characteristics, coexisting medical conditions, and chronic medications. Exhaustive data, including clinical parameters, blood test results and chest CT scan characteristics (when performed), were recorded at admission. Chest CT scan results were assessed, according to European guidelines [18], by a senior radiologist at the local workstation of each centre. The degree of scanographic lesions was based on visual assessment of parenchymal involvement and was categorized as limited (< 25%), moderate (25 − 50%), or severe (> 50%). Only CT scans performed within 24 hours of admission were considered.

Structural heart disease was defined as any abnormality or defect of the heart muscle or heart valves and was divided into ischaemic (coronary artery disease [CAD]-related) or other (non–CAD-related) structural heart disease.

Cardiovascular complications during hospitalization were reported and included any cardiac or vascular complication during in-hospital stay (acute coronary syndrome, acute heart failure, pericarditis, myocarditis, stroke, acute organ or limb ischaemia, pulmonary embolism, and deep vein thrombosis).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was in-hospital death. The secondary outcome was a composite of in-hospital death or ICU transfer. Data on pharmacological therapies, modes of respiratory support, complications or associated diagnoses during hospital stay were reported. All medical interventions, including pharmacological therapies to treat COVID-19, were left to the discretion of the referring medical team. The date of final follow-up for patients still hospitalized was 21 April 2020.

Statistical analysis

This report was prepared according to the STROBE checklist for observational studies [19]. Categorical data are reported as counts and percentages. Continuous data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data and as median (interquartile range [IQR]) for non-normally distributed data. Comparisons used the Chi2 test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and Student's t-test or the Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test, as appropriate, for continuous variables. Cox proportional hazard models were used to identify factors associated with in-hospital death in univariate and multivariable analysis. Variables with probability values < 0.20 in univariable analyses were considered in the multivariable models, with the final selection based on the most favourable goodness-of-fit measures (Bayesian information criterion). Kaplan–Meier survival curves were plotted and were compared using the log-rank test. Censoring occurred in the event of loss to follow-up. A 2-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data were analysed using R software, version 3.6.3 (R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 2878 patients were included from 26 February to 20 April 2020. The mean age was 66.6 ± 17.0 years and 57.9% were men. Baseline clinical characteristics at admission are detailed in Table 1 . Median time from the beginning of symptoms until hospital admission was 7.0 (3.0 − 10.0) days.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study population, overall and according to vital status.

| Variable | N | Overall (N = 2878) | Alive (n = 2503) | Died in hospital (n = 360) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age (years) | 2873 | 66.6 ± 17.0 | 64.6 ± 16.7 | 80.4 ± 12.0 | < 0.001 |

| Male sex | 2878 | 1666 (57.9) | 1434 (57.3) | 222 (61.7) | 0.18 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 2493 | 27.8 ± 6.0 | 27.9 ± 6.1 | 26.9 ± 5.8 | 0.003 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||||

| Hypertension | 2859 | 1453 (50.8) | 1186 (47.7) | 261 (72.9) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 2860 | 677 (23.7) | 554 (22.3) | 121 (33.9) | < 0.001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 2859 | 800 (28.0) | 654 (26.3) | 139 (38.9) | < 0.001 |

| Smoking | 2810 | 378 (13.5) | 325 (13.3) | 51 (14.7) | 0.29 |

| Heredity | 2713 | 44 (1.6) | 36 (1.52) | 7 (2.11) | 0.45 |

| Obesity | 2493 | 756 (30.3) | 677 (31.0) | 78 (26.0) | 0.09 |

| Coexisting conditions | |||||

| Peripheral artery disease | 2838 | 147 (5.2) | 117 (4.7) | 30 (8.4) | 0.001 |

| Stroke | 2837 | 253 (8.9) | 197 (8.0) | 54 (15.2) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2836 | 405 (14.3) | 282 (11.4) | 119 (33.9) | < 0.001 |

| Respiratory comorbidities | 2878 | < 0.001 | |||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 164 (5.7) | 125 (5.0) | 36 (10.0) | ||

| Asthma | 189 (6.6) | 170 (6.8) | 17 (4.7) | ||

| Chronic respiratory failure | 79 (2.7) | 62 (2.5) | 17 (4.7) | ||

| Malignancy | 2878 | < 0.001 | |||

| In remission | 226 (7.9) | 183 (7.3) | 43 (11.9) | ||

| Active | 189 (6.6) | 144 (5.8) | 42 (11.7) | ||

| Venous thromboembolism | 2878 | 212 (7.4) | 174 (7.0) | 38 (10.6) | 0.01 |

| Previous structural heart disease | 2850 | 599 (21.0) | 458 (18.5) | 136 (38.1) | < 0.001 |

| CAD | 313 (11.0) | 237 (9.6) | 75 (21.0) | ||

| Non-CAD | 286 (10.0) | 221 (8.9) | 61 (17.1) | ||

| Atrial fibrillation | 2852 | 416 (14.6) | 320 (12.9) | 91 (25.5) | < 0.001 |

| Previous heart surgery | 2878 | 105 (3.7) | 82 (3.3) | 21 (5.83) | 0.01 |

| Heart failure | 2809 | 317 (11.3) | 238 (9.7) | 79 (22.6) | < 0.001 |

| HFpEF | 161 (50.8) | 124 (5.0) | 37 (10.6) | < 0.001 | |

| HFrEF | 156 (49.2) | 114 (4.6) | 42 (12.0) | < 0.001 | |

| Chronic medications | |||||

| Beta-blocker | 2878 | 735 (25.5) | 585 (23.4) | 145 (40.3) | < 0.001 |

| Any RAAS-inhibitor | 966 (33.6) | 806 (32.2) | 156 (43.3) | < 0.001 | |

| ACE inhibitor | 2878 | 506 (17.6) | 423 (16.9) | 82 (22.8) | 0.003 |

| ARB | 2878 | 469 (16.3) | 392 (15.7) | 74 (20.6) | 0.02 |

| Diuretic | 2878 | 564 (19.6) | 446 (17.8) | 113 (31.4) | < 0.001 |

| Antialdosterone | 2878 | 79 (2.7) | 59 (2.4) | 20 (5.6) | 0.001 |

| Antiplatelet | 2878 | 627 (21.8) | 493 (19.7) | 131 (36.4) | < 0.001 |

| Oral antidiabetic | 2878 | 451 (15.7) | 374 (14.9) | 75 (20.8) | 0.004 |

| Statins | 2878 | 653 (22.7) | 540 (21.6) | 113 (31.4) | < 0.001 |

| Anticoagulant | 2878 | 418 (14.5) | 325 (13.0) | 90 (25.0) | < 0.001 |

| NOAC | 232 (8.1) | 184 (7.35) | 47 (13.1) | < 0.001 | |

| Anti-Xa | 100 (3.5) | 79 (3.2) | 21 (5.8) | ||

| Anti-IIa | 132 (4.6) | 104 (4.2) | 27 (7.5) | ||

| Vitamin K antagonist | 2878 | 150 (5.2) | 112 (4.47) | 37 (10.3) | < 0.001 |

| Heparin | 2878 | 30 (1.0) | 25 (1.00) | 4 (1.11) | 1.00 |

Data are expressed as number (%) or mean ± SD. Fifteen patients with unknown final status were excluded from the analysis. ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB: angiotensin II receptor blocker; BMI: body mass index; CAD: coronary artery disease; HFpEF: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; NOAC: non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant; RAAS: renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

Overall, 2088 (72.6%) of patients had at least one cardiovascular risk factor, 1196 (41.6%) had two, 570 (19.9%) had three and 210 (7.3%) had four. The most common risk factors were hypertension (50.8%), obesity (30.3%), dyslipidaemia (28.0%) and diabetes (23.7%). The main cardiovascular comorbidities were atrial fibrillation (14.6%), heart failure (11.3%), and CAD (11.0%). Among 317 patients with a history of heart failure, 50.8% had a preserved ejection fraction (defined as left ventricular ejection fraction > 50%) and 49.2% had a reduced ejection fraction (left ventricular ejection fraction < 50%). Chronic kidney disease (14.3%) and respiratory diseases (15.0%) were the most prevalent extra-cardiac conditions.

Paraclinical features

A positive SARS-CoV2 real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction test was documented in 2596 (91.8%) patients. Biological, electrocardiogram and imaging data are presented in Table 2 . An inflammatory profile was observed, with increased blood rates of C-reactive protein (90.3 ± 77.1 mg/L), fibrinogen (6.0 ± 1.7 g/L) and D-dimer (1644 ± 3633 μg/L). A high proportion of patients had a quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score (qSOFA) ≥ 2 (61.5%) or sepsis-induced coagulopathy score ≥ 1 (67.9%). On the CT-scan data, 80.9% of patients had mild or moderate parenchymal involvement, and 19.1% had > 50% of parenchymal involvement.

Table 2.

Paraclinical features of the study population, overall and according to vital status.

| Variable | N | Overall (N = 2878) | Alive (n = 2503) | Died in hospital (n = 360) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory values | |||||

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 2835 | 13.1 ± 2.0 | 13.2 ± 1.9 | 12.7 ± 2.2 | < 0.001 |

| Leucocytes (g/L) | 2827 | 7.3 ± 5.1 | 7.1 ± 4.6 | 9.0 ± 7.8 | < 0.001 |

| Lymphocytes (g/L) | 2785 | 1.3 ± 3.5 | 1.3 ± 2.7 | 1.6 ± 6.7 | 0.07 |

| Platelets (g/L) | 2807 | 220 ± 99 | 223 ± 99 | 203 ± 101 | 0.001 |

| GFR (mL/min/m2) | 2829 | 81.6 ± 29.5 | 84.6 ± 28.1 | 61.8 ± 31.3 | < 0.001 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L) | 2608 | 53.7 ± 69.0 | 50.9 ± 62.5 | 72.8 ± 102 | < 0.001 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/L) | 2423 | 10.9 ± 13.4 | 10.6 ± 13.4 | 12.2 ± 10.2 | 0.04 |

| Gamma glutamyl transferase (IU/L) | 2301 | 92 ± 31 | 90 ± 127 | 106 ± 156 | 0.04 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 2366 | 90 ± 119 | 88 ± 120 | 108 ± 108 | 0.003 |

| Phosphoraemia (mmol/L) | 1077 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.97 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 |

| Corrected serum calcium (mmol/L) | 1258 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.4 (0.2) | 2.5 (0.3) | 0.003 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 1642 | 31.8 ± 6.5 | 32.1 ± 6.5 | 29.8 ± 6.2 | < 0.001 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 2758 | 90.3 ± 77.1 | 85.7 ± 74.3 | 121.0 ± 85.9 | < 0.001 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 1379 | 6.0 ± 1.7 | 6.0 ± 1.7 | 6.0 ± 1.5 | 0.91 |

| Prothrombin rate (%) | 2215 | 85.0 ± 18.1 | 85.9 ± 17.6 | 78.4 ± 20.3 | < 0.001 |

| D-dimer (μg/L) | 1156 | 1644 ± 3633 | 1481 ± 2407 | 3025 ± 8624 | 0.051 |

| pH | 2006 | 7.5 ± 0.1 | 7.5 ± 0.1 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | < 0.001 |

| Lactates (mmol/L) | 1756 | 1.4 ± 1.0 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 1.6 | < 0.001 |

| Elevated BNP or NT-pro-BNPa | 1778 | 943 (53.0) | 702 (47.2) | 234 (83.6) | < 0.001 |

| Troponin elevationb | 1763 | 572 (32.4) | 442 (28.8) | 127 (58.5) | < 0.001 |

| qSOFA score ≥ 2 | 2109 | 1298 (61.5) | 1094 (59.8) | 196 (73.4) | < 0.001 |

| Sepsis-induced coagulopathy score > 1 | 1672 | 1135 (67.9) | 969 (66.2) | 162 (80.2) | < 0.001 |

| Electrocardiogram | |||||

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 2624 | 86.6 ± 17.9 | 86.5 ± 17.6 | 87.8 ± 20.2 | 0.16 |

| Complete bundle-branch block | 2121 | 164 (7.7) | 122 (6.5) | 42 (17.4) | < 0.001 |

| Non-sinus rhythm | 2312 | 260 (11.2) | 196 (9.7) | 64 (23.3) | < 0.001 |

| Corrected QT-segment (ms) | 1162 | 435 ± 51 | 433 ± 50 | 458 ± 55 | < 0.001 |

| Chest computed tomography | |||||

| Parenchymal involvement | 2247 | < 0.001 | |||

| Mild (< 30) | 953 (42.4) | 874 (43.9) | 77 (31.2) | ||

| Moderate (30 − 50) | 864 (38.5) | 764 (38.4) | 96 (38.9) | ||

| Severe (> 50) | 430 (19.1) | 353 (17.7) | 74 (30.0) |

Data are expressed as number (%) or mean ± SD. Fifteen patients with unknown final status were excluded from the analysis. BNP: B-type natriuretic peptide; GFR: glomerular filtration rate; NT − pro-BNP: N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; qSOFA: quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

BNP > 50 pg/mL or NT-pro-BNP > 300 pg/mL.

Above each centre threshold.

Cardiac biomarkers were increased (B-type natriuretic peptide [BNP] > 50 pg/mL or NT-pro-BNP > 300 pg/mL) in 53.0% of patients and troponin level was increased (above each centre threshold) in 32.4%.

Outcomes

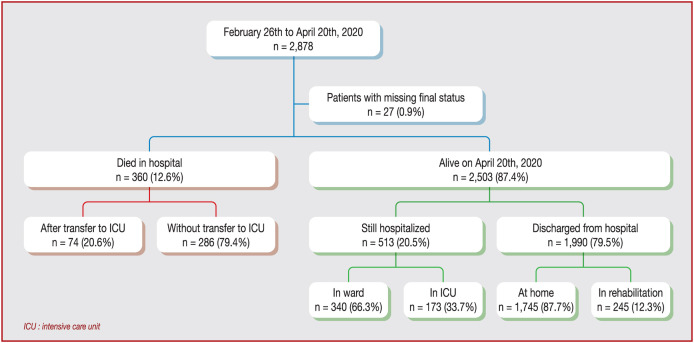

Of the 2878 patients included, 360 (12.5%) died in the hospital setting, of which 74 (20.6%) were transferred to ICU before death (Fig. 1 ). Median delay before transfer to ICU was 2 (IQR 1 − 4) days and before death without transfer to ICU was 6.5 (IQR 3 − 10) days. Mechanical ventilation was used in 370 (12.9%) patients, non-invasive ventilation support in 81 (2.8%) and high-flow oxygen therapy in 153 (5.3%). Median length of hospitalization among the 1991 patients discharged alive was 8 (IQR 5 − 12) days. As of 21 April 2020, of the 2503 patients still alive, 513 (20.5%) were still hospitalized, including 264 initially transferred to ICU and 249 patients not admitted to ICU.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart. ICU: intensive care unit.

Pharmacological treatments for COVID-19 included antibiotics in 2142 (74.4%) patients, hydroxychloroquine in 499 (17.3%), antiretrovirals in 378 (13.1%), corticosteroids in 214 (7.4%), immunomodulatory drugs in 33 (1.1%), recombinant interferon in 13 (0.5%) and immunoglobulin therapy in 2 (0.1%).

Risk factors associated with the primary outcome

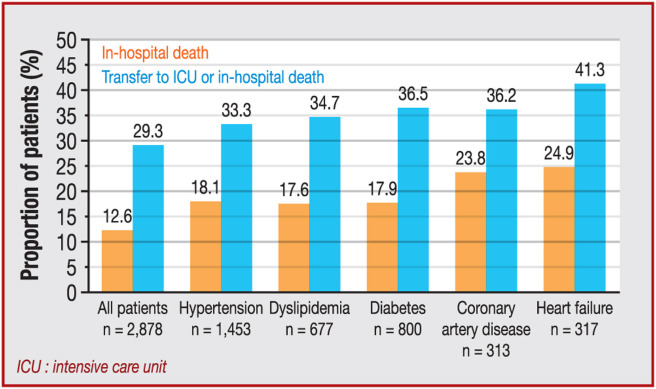

Factors associated with in-hospital death in univariable analysis are reported in Table 3 . Among cardiovascular comorbidities and risk factors, hypertension (P < 0.001), diabetes (P < 0.001), dyslipidaemia (P < 0.001), heart failure (P < 0.001), atrial fibrillation (P < 0.001) and history of structural heart disease (P < 0.001 for CAD and P < 0.001 for non-CAD) were associated with a higher likelihood of in-hospital death. The impact of main cardiovascular comorbidities is shown in Fig. 2 .

Table 3.

Cox univariate analysis.

| Variable | Alive (n = 2503) | Died in hospital (n = 360) | HR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | 64.6 ± 16.7 | 80.4 ± 12.0 | 1.07 (1.06 − 1.08) | < 0.001 |

| Male sex | 1434 (57.3) | 222 (61.7) | 1.16 (0.94 − 1.43) | 0.18 |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 27.9 (6.1) | 27.0 (5.8) | 0.97 (0.95 − 0.99) | 0.003 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||||

| Hypertension | 1186 (47.7) | 261 (72.9) | 2.84 (2.25 − 3.59) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 554 (22.3) | 121 (33.9) | 1.75 (1.41 − 2.18) | < 0.001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 654 (26.3) | 139 (38.9) | 1.73 (1.40 − 2.14) | < 0.001 |

| Smoking | 325 (13.3) | 51 (14.7) | 1.17 (0.87 − 1.58) | 0.29 |

| Obese | 677 (31.0) | 78 (26.0) | 0.80 (0.62 − 1.04) | 0.09 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 282 (11.4) | 119 (33.9) | 3.55 (2.84 − 4.43) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic respiratory failure | 62 (2.5) | 17 (4.7) | 1.90 (1.16 − 3.09) | 0.009 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 117 (4.7) | 30 (8.4) | 1.90 (1.31 − 2.77) | 0.001 |

| Stroke | 197 (8.0) | 54 (15.2) | 1.96 (1.47 − 2.62) | < 0.001 |

| Venous thromboembolism | 174 (7.0) | 38 (10.6) | 1.55 (1.11 − 2.18) | 0.01 |

| Previous structural heart disease | < 0.001 | |||

| None | 2020 (81.5) | 221 (61.9) | Referent | |

| CAD | 237 (9.6) | 75 (21.0) | 2.68 (2.06 − 3.48) | < 0.001 |

| Non-CAD | 221 (8.9) | 61 (17.1) | 2.42 (1.83 − 3.22) | < 0.001 |

| Heart failure | 238 (9.7) | 79 (22.6) | 2.53 (1.97 − 3.25) | < 0.001 |

| HFpEF | 124 (5.1) | 37 (10.6) | 2.09 (1.48 − 2.94) | < 0.001 |

| HFrEF | 114 (4.6) | 42 (12.0) | 2.60 (1.88 − 3.59) | < 0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 320 (12.9) | 91 (25.5) | 2.26 (1.78 − 2.87) | < 0.001 |

| Treatments | ||||

| Beta-blocker | 423 (16.9) | 82 (22.8) | 1.44 (1.13 − 1.84) | 0.003 |

| Any RAAS-inhibitor | 806 (32.2) | 156 (43.3) | 1.58 (1.28 − 1.94) | < 0.001 |

| ACE inhibitor | 423 (16.9) | 82 (22.8) | 1.44 (1.13 − 1.84) | 0.003 |

| ARB | 392 (15.7) | 74 (20.6) | 1.36 (1.05 − 1.76) | 0.002 |

| Biomarkers | ||||

| Elevated BNP or NT − pro-BNPa | 702 (47.2) | 234 (83.6) | 5.30 (3.86 − 7.27) | < 0.001 |

| Troponin elevationb | 442 (28.8) | 127 (58.5) | 3.23 (2.46 − 4.24) | < 0.001 |

| qSOFA score ≥ 2c | 1094 (59.8) | 196 (73.4) | 1.81 (1.38 − 2.38) | < 0.001 |

Data are expressed as number (%) unless otherwise specified. Fifteen patients with unknown final status were excluded from the analysis. ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB: angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI: body mass index; BNP: B-type natriuretic peptide; CAD: coronary artery disease; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HFpEF: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; NT − pro-BNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

BNP > 50 pg/mL or NT-pro-BNP > 300 pg/mL.

Above each centre threshold.

Initial severity score.

Figure 2.

Impact of cardiovascular comorbidities on outcomes in patients hospitalized for COVID-19 in France. ICU: intensive care unit.

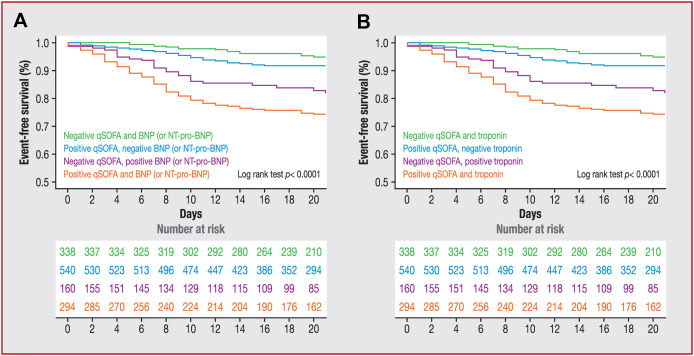

After adjustment for heart failure status, elevated BNP or NT − pro-BNP levels were independently associated with in-hospital death (HR 5.01, 95% CI 3.61 − 6.95; P < 0.001). After adjustment for heart failure and CAD, troponin elevation remained associated with in-hospital death (HR 2.86, 95% CI 2.15 − 3.81; P < 0.001). Considering the contribution of two combined markers (qSOFA and troponin or BNP/NT − pro-BNP) to refine the prognosis, the addition of two abnormal markers was significantly associated with a poor outcome (Fig. 3 ).

Figure 3.

Survival according to (A) qSOFA and BNP or NT-pro-BNP elevation; or (B) qSOFA and troponin elevation. qSOFA positive was defined as a score ≥ 2. Elevated troponin was defined as that above each centre threshold. Elevated cardiac biomarkers were BNP > 50 pg/mL or NT − pro-BNP > 300 pg/mL. BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; NT − pro-BNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; qSOFA, quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

In multivariable analysis, age (P < 0.001), male sex (P = 0.005), diabetes (P = 0.009), chronic kidney failure (P < 0.001) and heart failure (P = 0.04) were independently associated with in-hospital death (Table 4 ). After including cardiac biomarkers and clinical severity (qSOFA ≥ 2 at admission) in the model, age (P < 0.001), male sex (P = 0.01), diabetes (P = 0.01), chronic kidney failure (P = 0.04), elevated troponin (P = 0.01), elevated BNP or NT − pro-BNP (P = 0.049) and positive qSOFA score (P = 0.01) remained independently associated with in-hospital death.

Table 4.

Cox multivariable analysis.

| Variable | Model 1: baseline coexisting conditions |

Model 2: baseline coexisting conditions, cardiac biomarker elevation and clinical severity |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age per 1-year increase | 1.07 (1.06 − 1.08) | < 0.001 | 1.05 (1.03 − 1.06) | < 0.001 |

| Male sex | 1.45 (1.12 − 1.86) | 0.005 | 1.69 (1.11 − 2.57) | 0.01 |

| Obese | 1.16 (0.87 − 1.55) | 0.32 | 1.05 (0.67 − 1.65) | 0.83 |

| Hypertension | 1.00 (0.74 − 1.36) | 0.99 | 0.94 (0.58 − 1.54) | 0.82 |

| Diabetes | 1.44 (1.09 − 1.89) | 0.009 | 1.72 (1.12 − 2.63) | 0.01 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 1.12 (0.86 − 1.46) | 0.41 | 1.10 (0.73 − 1.66) | 0.65 |

| Chronic kidney failure | 1.61 (1.22 − 2.11) | < 0.001 | 1.57 (1.02 − 2.41) | 0.04 |

| Chronic respiratory failure | 1.31 (0.75 − 2.29) | 0.35 | 1.64 (0.74 − 3.62) | 0.22 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1.02 (0.74 − 1.40) | 0.90 | 0.76 (0.47 − 1.23) | 0.26 |

| Chronic heart failure | 1.37 (1.01 − 1.84) | 0.04 | 1.21 (0.76 − 1.92) | 0.43 |

| Previous stroke | 0.94 (0.67 − 1.31) | 0.70 | 0.77 (0.45 − 1.31) | 0.33 |

| Elevated troponina | − | − | 1.66 (1.11 − 2.49) | 0.01 |

| Elevated BNP or NT − pro-BNPb | − | − | 1.69 (1.00 − 2.86) | 0.049 |

| qSOFA ≥ 2 | − | − | 1.71 (1.12 − 2.60) | 0.01 |

BNP: B-type natriuretic peptide; CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; NT − pro-BNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; qSOFA: quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Above each centre threshold.

BNP > 50 pg/mL or NT − pro-BNP > 300 pg/mL.

Cardiovascular complications

The rate of cardiovascular complications was higher among the 360 patients who died in hospital compared with patients still alive (26.9% vs. 16.9%, P < 0.001) (Table 5 ). Of those who died, 15.6% (n = 56) had an acute decompensation of heart failure (at admission or during hospitalization). Myocarditis (P = 0.007) and stroke (P = 0.001) were more prevalent among patients who died.

Table 5.

Comparison of cardiovascular complications according to vital status.

| Complication | Vital status |

P | Transfer to ICU or in-hospital death |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive (n = 2503) | Died in hospital (n = 360) | No (n = 2034) | Yes (n = 835) | |||

| De novo left ventricular dysfunction | 16 (0.7) | 6 (1.8) | 0.005 | 13 (0.7) | 9 (1.4) | 0.11 |

| Any cardiovascular complication | 423 (16.9) | 97 (26.9) | < 0.001 | 310 (15.2) | 210 (25.1) | < 0.001 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 27 (1.1) | 9 (2.5) | 0.02 | 24 (1.2) | 11 (1.3) | 0.82 |

| Acute heart failure | 129 (5.2) | 56 (15.6) | < 0.001 | 98 (4.8) | 86 (10.3) | < 0.001 |

| Pericarditis | 16 (0.6) | 3 (0.8) | 0.58 | 14 (0.7) | 5 (0.6) | 0.93 |

| Myocarditis | 15 (0.6) | 7 (1.9) | 0.007 | 11 (0.5) | 11 (1.3) | 0.04 |

| Stroke | 14 (0.6) | 8 (2.2) | 0.001 | 9 (0.4) | 13 (1.6) | 0.004 |

| Acute organ or limb ischaemia | 10 (0.4) | 5 (1.4) | 0.01 | 7 (0.3) | 8 (1.0) | 0.03 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 94 (3.7) | 9 (2.5) | 0.64 | 62 (3.1) | 44 (5.3) | < 0.001 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 33 (1.3) | 3 (0.8) | 0.39 | 14 (0.7) | 23 (2.8) | < 0.001 |

| Other | 99 (4.0) | 14 (3.9) | 0.73 | 77 (3.8) | 36 (4.3) | 0.62 |

Data are expressed as number (%). Fifteen patients with unknown final status were excluded from the analysis. ICU: intensive care unit.

Discussion

This is, to our knowledge, the first cohort study to provide comprehensive insights into patients hospitalized for COVID-19 in France. More than three of four patients had at least one cardiovascular risk factor. Advancing patient age, male sex, and history of diabetes, chronic kidney failure or chronic heart failure were independently associated with risk of in-hospital death. Elevation of cardiac biomarkers was also associated with risk of death. Cardiovascular complications during hospitalization contributed significantly to in-hospital death.

Our population of 2878 hospitalized patients was predominantly male and aged over 60 years, consistent with previous studies showing a greater percentage of male versus female patients [7], [11], [14]. Reports show that the proportion of men is even higher among those hospitalized direct to the ICU for COVID-19 [12], [15]. In our study, the rate of patients with at least one cardiovascular risk factor is high, due mainly to a high prevalence of hypertension, whereas CAD and heart failure were less prevalent. This is consistent with previous studies among American or European patients hospitalized for COVID-19, which reported more than half of patients with hypertension and one-third with any cardiovascular comorbidity [7], [11], [14], [19].

Initially, it was suspected that patients taking renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors may be at increased risk of SARS-CoV2 infection. This hypothesis was based on the frequent coexistence of a cardiovascular context in patients infected with SARS-CoV2 and on the pathophysiological role of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 molecules in binding the virus to infect the cell [20]. However, there is growing evidence to show that renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors are not harmful in COVID-19 [21]. Indeed, the severity of the disease is rather related to a heavy cardiovascular load than to the drugs used to treat it [22], [23]. In addition, we found no correlation between renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors and in-hospital death after adjustment for hypertension and heart failure [21].

The death rate was estimated to be around 12.5% among patients hospitalized for COVID-19 in our study. This mortality rate is slightly lower than that reported in other studies, which ranged from 20% to 25% [11], [14], [24]. This discrepancy could be explained by the exclusion of patients admitted direct to ICU, whereas several previous studies included all consecutive patients admitted to hospital, regardless of their initial severity, leading to a high mortality rate. Another explanation might be the inclusion of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 during the same period at all centres. However, we reported that almost 20% of patients were transferred to ICU for respiratory support, which is higher than that for cohorts of patients hospitalized in a conventional ward [11]. Taken together, these findings suggest that the severity of the patients in this cohort is similar to that in another French study [25].

COVID-19 can cause cardiovascular complications such as myopericarditis, pulmonary embolism and acute coronary syndrome. Even if these complications remain infrequent, as shown in our sample, they are associated with a poor prognosis [26], [27]. In parallel, we noted that elevated BNP/NT-pro-BNP or troponin was associated with in-hospital death, even in patients free of a history of CAD or heart failure. This finding might be related to subclinical myocardial damage caused by SARS-CoV2 [28]. Indeed, myocardial injury has been described as common among patients with COVID-19 and is associated with severe or fatal forms [28]. The main hypothesis that underlies this is the binding of SARS-CoV2 virus to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor to infect the cell [20]. More than 7% of myocardial cells express angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, which could explain how the SARS-CoV2 virus enters cardiomyocytes and causes direct cardiotoxicity [20], [22], [26]. Furthermore, cardiovascular tropism of SARS-CoV2 could even be more intense in patients with heart failure or diabetes. Among these patients, upregulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 has been described, leading to an increased rate of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptors and thus a greater propensity to become infected with SARS-CoV2 [29].

We acknowledge some limitations. First, we report a small proportion of the total number of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 in France, included in several areas with, at this time, no recommendations regarding in-hospital management. This may lead to slight heterogeneity in the study population; however, this is inherent to the study of infectious diseases. Second, this study, even if multicentre, describes the characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized in France. Caution must be exercised in generalizing these results to other regions or countries. Third, we cannot exclude the possibility of changes in the characteristics of infected patients in a second wave. There may be future mutations in the SARS-CoV2 virus that will alter its infectious characteristics and thus the affected population [30]. Therefore, the information acquired in the first wave should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions

In this multicentre cohort study, we provide insights into the characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in France. Cardiovascular comorbidities and cardiovascular risk factors carry a substantial morbi-mortality burden in this population. Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 who have cardiovascular disease must be closely monitored as they are at increased risk of in-hospital death.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acvd.2021.01.003.

Online Supplement. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Dong E., Du H., Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. [S1473309920301201] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). n.d. https://www.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6.(accessed October 25, 2020).

- 3.Ali I. COVID-19: are we ready for the second wave? Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020:1–3. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2020.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu S., Li Y. Beware of the second wave of COVID-19. The Lancet. 2020;395:1321–1322. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30845-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.SPF. COVID-19: point épidémiologique du 22 octobre 2020 n.d./maladies-et-traumatismes/maladies-et-infections-respiratoires/infection-a-coronavirus/documents/bulletin-national/covid-19-point-epidemiologique-du-22-octobre-2020.(accessed October 26, 2020).

- 6.Chen R., Liang W., Jiang M., Guan W., Zhan C., Wang T., et al. Risk factors of fatal outcome in hospitalized subjects with coronavirus disease 2019 from a nationwide analysis in China. Chest. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.010. [S0012369220307108] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guan W., Ni Z., Hu Y., Liang W., Ou C., He J., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [NEJMoa2002032] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo W.-Q., Chen X.-H., Tian X.-Y., Li L. Differences in gastrointestinal safety profiles among novel oral anticoagulants: evidence from a network meta-analysis. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:911–921. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S219335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cummings M.J., Baldwin M.R., Abrams D., Jacobson S.D., Meyer B.J., Balough E.M., et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31189-2. [S0140673620311892] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goyal P., Choi J.J., Pinheiro L.C., Schenck E.J., Chen R., Jabri A., et al. Clinical characteristics of Covid-19 in New York City. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010419. [NEJMc2010419] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richardson S., Hirsch J.S., Narasimhan M., Crawford J.M., McGinn T., Davidson K.W., et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grasselli G., Zangrillo A., Zanella A., Antonelli M., Cabrini L., Castelli A., et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inciardi R.M., Adamo M., Lupi L., Cani D.S., Di Pasquale M., Tomasoni D., et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 and cardiac disease in Northern Italy. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1821–1829. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Docherty A.B., Harrison E.M., Green C.A., Hardwick H.E., Pius R., Norman L., et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO clinical characterisation protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020:m1985. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang J., Zheng Y., Gou X., Pu K., Chen Z., Guo Q., et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis IJID Off Publ Int Soc Infect Dis. 2020;94:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao Q., Meng M., Kumar R., Wu Y., Huang J., Lian N., et al. The impact of COPD and smoking history on the severity of COVID-19: A systemic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hussain A., Bhowmik B., do Vale Moreira N.C. COVID-19 and diabetes: knowledge in progress. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;162:108142. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stefan N., Birkenfeld A.L., Schulze M.B., Ludwig D.S. Obesity and impaired metabolic health in patients with COVID-19. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:341–342. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-0364-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suleyman G., Fadel R.A., Malette K.M., Hammond C., Abdulla H., Entz A., et al. Clinical characteristics and morbidity associated with Coronavirus Disease 2019 in a series of patients in Metropolitan Detroit. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2012270. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lévy B.I., Fauvel J.-P., Société Française d’Hypertension Artérielle Renin-angiotensin system blockers and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;113:572–578. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2020.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lopes R.D., Macedo A.V.S., de Barros E., Silva P.G.M., Moll-Bernardes R.J., Feldman A., et al. Continuing versus suspending angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers: Impact on adverse outcomes in hospitalized patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)--The BRACE CORONA Trial. Am Heart J. 2020;226:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng Y.-Y., Ma Y.-T., Zhang J.-Y., Xie X. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:259–260. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baral R., White M., Vassiliou V.S. Effect of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with COVID-19: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of 28,872 Patients. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2020;22:61. doi: 10.1007/s11883-020-00880-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. The Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fauvel C., Weizman O., Trimaille A., Mika D., Pommier T., Pace N., et al. Pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients: a French multicentre cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2020:ehaa500. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang Y., Chen T., Mui D., Ferrari V., Jagasia D., Scherrer-Crosbie M., et al. Cardiovascular manifestations and treatment considerations in COVID-19. Heart. 2020;106:1132–1141. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hulot J.-S. COVID-19 in patients with cardiovascular diseases. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;113:225–226. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2020.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi S., Qin M., Shen B., Cai Y., Liu T., Yang F., et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishiga M., Wang D.W., Han Y., Lewis D.B., Wu J.C. COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease: from basic mechanisms to clinical perspectives. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:543–558. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0413-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chiappelli F. CoViD-19 Susceptibility. Bioinformation. 2020;16:501–504. doi: 10.6026/97320630016501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.