Abstract

Background

Prolonged survival period as a result of early diagnosis and treatment in breast cancer has increased the importance of postoperative morbidities. The aim of the present study was to investigate the association of pain catastrophizing with shoulder pain in patients with decreased shoulder range of motion in the postoperative period.

Patients and Methods

The present study included 53 patients who underwent surgery due to breast cancer. Patients who had bilateral mastectomy, distant metastases, cervical-cranial originated lesions, patients with problems involving one of the shoulders or upper extremities before the operation, and patients with cognitive impairment, heart failure, or low albumin levels (liver parenchyma disease or renal failure) were excluded. Shoulder range of motion was measured in the postoperative period, and two study groups were established: one with a limited shoulder range of motion level and the other with a normal level. Effects of pain catastrophizing and shoulder pain severity on shoulder range of motion limitation were compared between the two groups.

Results

The average age of 53 female patients who had breast surgery was 52.3 ± 10.5 years. In the group with limited shoulder range of motion, the median pain catastrophizing scale value was 27 (range 5–32) and the shoulder pain severity score was 4 (range 0–8), while in the group with normal shoulder range of motion these values were 11 (range 3–39) and 2 (range 0–6), respectively (p < 0.05). In addition, it was found that factors such as surgical treatment modality and postoperative radiotherapy did not significantly affect shoulder range of motion limitation.

Conclusion

Determining the pain catastrophizing scale of patients and controlling pain in the early postoperative period could have positive effects on shoulder range of motion.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Surgical treatment, Pain catastrophizing, Shoulder pain, Shoulder joint range of motion

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer type in women, and major treatment for this condition is surgery [1]. Due to the developments in screening and diagnostic methods, most patients get their diagnoses and treatment at earlier stages, such as stages I and II. While modified radical mastectomy (MRM) and breast-conserving surgery (BCS) are regular treatment modalities in breast cancer surgery, sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), or axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) could also be used upon the involvement of axillary lymph nodes. Following the treatment at an earlier phase, scar tissue formation, fibrosis, and shortening of soft tissues in the anterior thoracic and axillary regions may cause varying functional losses such as decreased range of mobility and strength [2]. However, chronic inflammatory changes and broken tissue integrity may lead to the development of tension and pain in the shoulder joint capsule and further complications [3]. Although the morbidities encountered after breast surgery could be due to anatomic and physical changes as a result of surgery as well as due to psychosocial reasons, 42–82% of the patients operated for breast cancer using ALND experience at least one of the musculoskeletal problems such as limitation of shoulder range of motion (ROM), shoulder pain (SP), loss of shoulder muscle strength, and lymphedema [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. In almost 20% of the patients with breast cancer, arm lymphedema after axillary dissection is seen [7, 8]. All these unwanted effects may cause additional difficulties in performing activities of daily life that is seen in 9–57% of the patients, consequently a reduced quality of life [8]. Development of arm problems and the likelihood of psychological distress due to impaired shoulder mobility and pain may remain a potential problem for patients undergoing breast cancer treatment.

Pain as a common complaint in the postoperative period of breast cancer patients sometimes poses a challenge to clinicians. Due to the fact that the perception of pain and its grading can be different in each individual, there are numerous studies mentioning the role of catastrophizing in the perception and grading of pain [10, 11]. Catastrophizing is defined as the affinity considering a situation much worse than it actually is, expecting the worst consequences, overestimating the possibility of negative results and exaggerating the responses. In relation to this, the pain catastrophizing scale (PCS) was developed by Sullivan et al. [12] in 1995 to evaluate the catastrophizing level of individuals. It was shown that perception and catastrophizing of the impact of pain is 7–33% higher depending upon the catastrophizing level [11, 13]. In addition, higher PCS scores were shown to be associated with deterioration of the quality of life and amount of analgesic drugs used in the postoperative period [10, 14].

Previous studies revealed that PCS was correlated with perioperative venipuncture pain and postoperative pain severity [15, 16, 17]. Therefore, it is logical to assume that shoulder movements may be associated with pain catastrophizing after breast surgery. Thus, we hypothesized that patients' catastrophizing of their pain or general appearance could limit postoperative shoulder ROM. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the association between pain catastrophizing and postoperative limitation of shoulder joint motions in patients who underwent surgical treatment due to breast cancer.

Patients and Methods

Study

A prospective cohort study on patients with breast cancer who had undergone surgical treatment was planned.

Patients

A total of 147 patients who had surgery (MRM or BCS) due to breast cancer at the Department of General Surgery, Gaziosmanpaşa University Faculty of Medicine, Research and Practice Hospital Center, Tokat, Turkey, between January 1, 2014, and August 1, 2017, were searched through a screening of the hospital database using the related ICD-10 codes. All searched patients were contacted via telephone and were informed about the study in detail. All patients with nonmetastatic breast cancer who underwent surgical treatment via MRM or BCS with SLNB or ALND ≥6 months after the surgery and were not receiving rehabilitation services in relation to breast cancer were included in the study. The patients who had bilateral mastectomy, distant metastases, any shoulder or upper-extremity problems of cervical-cranial origin before the operation, cognitive impairment, heart failure and albumin deficiency due to liver parenchyma disease and renal failure were excluded. Among the patients who matched the study criteria and were willing to participate, there were 53 patients with a response rate of 36%.

Patient Evaluations

Patients were interviewed about their age (years), BMI, education level (illiterate, primary/secondary/high school, and college/university), and side of the surgery. The type of surgical treatment (MRM/BCS, SLNB/BCS/ALND) and radiotherapy (RT) methods were recorded through inspecting the patient files. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (kg/m2).

The patients were informed before the physical examination and were asked to complete a translated and validated PCS-Turkish form [11]. Then, physical examination was performed. All measurements and evaluations were performed by an experienced physical therapist and a general surgeon.

In routine postoperative policy, arm exercises with informative pamphlets about how to protect their arm on the operated side starting from the first postoperative week were given to the patients. A comprehensive postoperative rehabilitation program for breast cancer patients was not performed during the study period.

Pain Catastrophizing

Pain catastrophizing was measured using PCS. It is a self-reporting questionnaire consisting of 13 items and is used to evaluate inappropriate coping strategies and catastrophic thinking of pain and related sense and emotions of individuals. The test whose validity and reliability for the Turkish population were verified by Süren et al. [11] (Cronbach's α = 0.90) is made of three dimensions: helplessness, magnification, and rumination. Each item is graded by points from 0 to 5, and higher scores indicate elevated levels of catastrophizing. The scale is evaluated based on the total score varying from 0 to 52 [12]. Suren et al. [15] calculated the PCS cutoff value as 17. Total scores <17 were considered normal, while those ≥17 were regarded as high.

Shoulder ROM Measurements

Active ROM was measured on both shoulders (on the operated and nonoperated sides) using a goniometer. All measurements were conducted by an experienced physical therapist who was blinded to the type of axillary surgery as either ALND or SLNB. Flexion and abduction ROMs were measured in supine position, extension ROM was measured in prone position, inner and outer rotation ROMs were measured in supine position while the shoulder was in a 90° abduction and 90° flexion position [7]. Using the measurements of the affected and unaffected sides, differences between ROM were calculated. For flexion and abduction, 180° were regarded as the normal ROM, while the normal ROM was 90° for inner and outer rotation [18]. A ROM limitation of ≥20° in the affected shoulder compared to the unaffected one in any aspect of the measurements (flexion, abduction, extension, inner and outer rotation) was regarded as shoulder limitation in the operated side [19]. All measurements were repeated by another experienced physical therapist to prevent reliability differences and minimize errors. The patients were grouped as limited and normal shoulder ROM based on the ≥20° differences between the affected and unaffected shoulders.

Pain Level

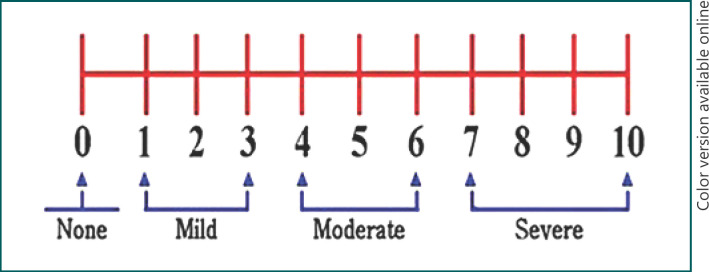

The presence of SP and its intensity were evaluated using a 10-cm numeric rating scale (NRS) as a reliable, easy-to-use method to evaluate subjective pain severity, which does not need verbal or reading skills [20]. The anchors were 0 = no pain and 10 = worst possible pain. Pain of the patients was graded into four groups based on the NRS scores during shoulder motion. The first group included the patients who had no pain (NRS = 0), the second group those with mild pain (NRS = 1, 2, or 3), the third group those with a moderate level of pain (NRS = 4, 5, or 6), and the fourth group included the patients with severe pain (NRS = >7) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Grading of pain based on the NRS.

Evaluation of Lymphedema

Girth measurements were performed through the circumferential assessment at the predetermined site on the operated and the nonoperated sides by using a tape measure. For this purpose, the circumferential length of the forearm was measured 10 cm proximal to the wrist. Differences up to 1.5 cm between the dominant and nondominant arms were considered normal. Three edema levels were determined based on the peripheral difference: minimal edema (≥1.5–<3 cm), moderate edema (3–5 cm), and severe edema (≥5 cm) [21].

Statistical Analysis

Shoulder ROM was regarded as the primary outcome. The secondary outcomes were the presence of SP and grading of lymphedema. Statistical evaluation of the data was carried out using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Normality of the data was checked using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed quantitative data (age and BMI) were expressed as arithmetic mean ± standard deviation, while those without normal distribution (PCS and SP) were expressed as median (min–max). Categorical data including SP grades, shoulder ROM groups, and lymphedema grades determined by counting, on the other hand, were expressed as number of individuals (n) and their percentage (%). PCS values, presence, and severity of pain (SP) on the operated and the nonoperated sides during resting and motion, shoulder ROM, and lymphedema (circumferential difference between the front arms) were compared between the patient groups. Significance test between the two means was used to compare shoulder ROM and lymphedema values of the operated and the nonoperated sides. χ2 test was used for comparing qualitative variables. p < 0.05 was considered significant in all statistical analyses.

Results

The study included 53 female patients with a mean age of 52.36 ± 10.51 years. Although BCS and MRM were performed in 27 (51%) and 26 patients (49.1%), respectively, ALND was performed in most of the patients (69.8%). Postoperative RT was needed in 44 patients (83.0%). Considering SP, the patients most commonly had mild pain (47.2%). Although 24.5% of the patients had minimal lymphedema, there was no moderate or severe lymphedema. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients in the study

| Age, years | 52.36±0.51 |

| BMI | 28.43±5.8 |

| Education level | |

| Illiterate | 6 (11.3) |

| Primary/secondary/high school | 41 (77.4) |

| College/university | 6 (11.3) |

| Type of surgery | |

| BCS (+SLNB) | 16 (30.2) |

| BCS (+ALND) | 11 (20.8) |

| MRM | 26 (49.1) |

| Type of lymph node dissection | |

| SLNB | 16 (30.2) |

| ALND | 37 (69.8) |

| Operation side | |

| Right | 30 (56.6) |

| Left | 23 (43.4) |

| Postoperative RT | |

| Yes | 44 (83.0) |

| No | 9 (17.0) |

| PCS score | |

| <17 | 36 (67.9) |

| .17 | 17 (32.1) |

| Shoulder ROM | |

| Limited | 11 (20.8) |

| Normal | 42 (79.2) |

| Shoulder pain | |

| No pain | 12 (22.6) |

| Mild pain | 25 (47.2) |

| Moderate pain | 15 (28.3) |

| Severe pain | 1 (1.8) |

| Grade of lymphedema (circumferential difference, cm) | |

| Normal (<1.5) | 40 (75.5) |

| Minimal (.1.5.<3) | 13 (24.5) |

| Moderate (3.5) | 0 (0) |

| Severe (.5) | 0 (0) |

Values are presents as mean ± standard deviation or n (%). BCS, breast-conserving surgery; MRM, modified radical mastectomy; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy; ALND, axillar lymph node dissection; RT, radiotherapy; PCS, pain catastrophizing scale; shoulder ROM, shoulder range of motion.

In 11 patients (20.8%), there was limited shoulder ROM. Median PCS score was significantly higher in patients with limited shoulder ROM (7 [range 5–32] vs. 11 [range 3–39], p = 0.002). In patients with limited shoulder ROM, NRS score for SP was significantly higher (4 [range 0–8] versus 2 [range 0–6], p = 0.043) (Table 2). There was no significant difference between the groups with regard to age, BMI, education level, types of surgery and ALND, operation sides, and postoperative RT (p > 0.05 for all) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of the patients with (n = 11) and without (n = 42) limited shoulder ROM

| Shoulder ROM |

p | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| normal | limited | ||

| Age, years | 52.33±11.26 | 52.45±7.33 | 0.9 |

| BMI | 28.90±6.14 | 26.64±4.01 | 0.2 |

| Education level | |||

| Illiterate | 5 (11.9) | 1 (9.1) | >0.05 |

| Primary/secondary/high school | 34 (81.0) | 7 (63.7) | |

| College/university | 3 (7.1) | 3 (27.3) | |

| Type of surgery | |||

| BCS (+SLNB) | 12 (28.6) | 4 (36.4) | >0.05 |

| BCS (+ALND) | 9 (21.4) | 2 (18.2) | |

| MRM | 21 (50) | 5 (45.5) | |

| Type of lymph node dissection | |||

| SLNB | 12 (28.6) | 4 (36.4) | >0.05 |

| ALND | 30 (71.4) | 7 (63.4) | |

| Operation side | |||

| Right | 26 (61.9) | 4 (36.4) | >0.05 |

| Left | 16 (38.1) | 7 (63.4) | |

| Postoperative RT | |||

| Yes | 36 (85.7) | 8 (73.8) | >0.05 |

| No | 6 (14.3) | 3 (37.3) | |

| PCS | 11 (3–39) | 27 (5–2) | 0.002 |

| SP | 2 (0–6) | 4 (0–8) | 0.043 |

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation, n (%), or median (min.-max.). PCS, pain catastrophizing scale; SP, shoulder pain; NRS, numeric rating scale; shoulder ROM, shoulder range of motion; BCS, breast-conserving surgery; MRM, modified radical mastectomy; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy; ALND, axillar lymph node dissection; RT, radiotherapy.

Shoulder ROM limitation was observed in 4 out of 36 patients (11.1%) with PCS <17, whereas 41.2% (7 out of 17) of the patients with PCS ≥17 had limitation (p < 0.001). In addition, the median pain level of the patients with PCS <17 was 2 (range 0–6), while the patients with PCS ≥17 had a median pain score of 5 (range 0–8) (p < 0.001).

Discussion

In the present study, we showed the significant association of shoulder ROM limitation with SP and PCS score in patients operated for breast cancer. There were more pain and higher pain catastrophizing in patients with limited shoulder ROM following treatment for breast cancer. However, we found no significant impact of the types of surgery and ALND, and postoperative RT on the development of shoulder ROM.

Advances in early diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer cause an increase in the lifespan of patients after surgery leading to quality of life considerations [3, 22, 23]. The most common upper-extremity complaints after breast surgery are limited shoulder ROM, shoulder pain, decreased shoulder and hand muscle strengths, and development of lymphedema. In their prospective study, Hidding et al. [24] reported that 62% of the patients operated for breast cancer had at least one of these complaints, while 27% of them had at least two. In follow-up studies of the patients operated for unilateral breast cancer, 22–53% of the patients suffered from SP on the operated side [23], 1–67% from shoulder ROM limitation [24], 9–28% from decreased shoulder muscle strength [24, 25], and 6–56% from lymphedema [26, 27]. Although the ranges for each complication show a variability, our rates for pain, limited shoulder ROM, and development of lymphedema could be regarded within the acceptable ranges indicating the generalizability of our results.

Limitation of shoulder ROM after surgery due to breast cancer is among the most common complaints of patients, impairing their quality of life [28]. It has been reported that limited shoulder ROM can be seen in 13–77% of the patients on operated sides [18, 29, 30, 31]. In In the study by Smoot et al. [19], 16.6% of the cases had restriction in shoulder abduction ROM at 12 months following surgery. Postoperative pain was thought to be strongly associated with shoulder ROM limitation [32]. Although previous studies did not reveal a significant effect of the type of surgical procedure as MRM, BCS, SLNB, or ALND on the severity of shoulder ROM limitation, Morimoto et al. [9] and Ernst et al. [33] showed that postoperative SP was affected by shoulder ROM limitation. In their studies on women operated for breast cancer, Box et al. [7] also found that the surgical method did not have any impact on shoulder ROM limitation. They also reported that early findings in postoperative period did not predict shoulder ROM limitation in the long term. In Ibrahim's study [2], the authors found that ROM limitations were significantly higher in patients with total mastectomy and radiation to the axilla. There have been controversial issues with regard to the impact of mastectomy on shoulder ROM. Besides the decreasing rates for mastectomy for the recent years, reductions in shoulder joint movements have been detected especially with abduction [20]. In addition, it has been also reported that restriction returns to normal as the follow up time progresses. However, in the present study, we found no relationship between the development of limited shoulder ROM and the type of surgery. In addition, there was no significant association between shoulder ROM and use of RT, side of the surgery, and demographic features of the patients. Considering the complex interactions of several factors including type of surgery as mastectomy or lumpectomy, type of surgery for axillary lymph nodes as ALND or SLNB, and extent of radiation therapy to the axilla, the outcomes in the present study may be different from other studies. Therefore, prospective studies in which such confounding variables are controlled are needed to reach more reliable results.

Pain catastrophizing is a term that has been used in the last 50 years to refer the failure of sensitive individuals to cope with the pain when they encounter painful situations [34]. Pain catastrophizing varies considerably among individuals, and this variation is influenced by social, cultural, environmental, psychological, and genetic factors [35, 36]. PCS is a test developed by Sullivan et al. [12] in 1995 to reveal how pain is experienced by individuals. There have been many clinical studies evaluating pain catastrophizing. In these studies, it was shown to be an independent risk factor for the onset and deterioration of chronic pain [34]. Van Eijsden-Besseling et al. [37] mentioned that manifestations and prognosis of pain was worse in patients with a high level of pain catastrophizing. Bergbom et al. [38], on the other hand, reported that catastrophizing predicts lack of healing and physical disability in patients with musculoskeletal diseases receiving physical therapy. Similarly, Sullivan et al. [39] studied the relationship between pain catastrophizing and actual physical intolerance in delayed-onset muscle pains caused by exercise. They observed development of physical intolerance in patients with a high level of pain catastrophizing. In another study, Crombez et al. [40] found that fear and catastrophizing due to pain in patients with chronic low back pain led to a high level of physical intolerance. Thilbault et al. [41], on the other hand, studied lifting bags filled with sand in patients with chronic muscle-skeletal system diseases and observed lower physical performance in patient groups with catastrophizing compared to a control group. Some authors tried to find a cutoff value to grade the level of pain catastrophizing as low or high. For that purpose, Suren et al. [15] determined a cutoff value of 17 for PCS for higher pain catastrophizing. In the present study, we used this cutoff value and found that shoulder ROM was limited in 41.2% of the patients with PCS ≥17. This significant difference can be regarded as a supportive evidence for the association of higher SP and pain catastrophizing in patients with limited shoulder ROM during the postoperative period for breast cancer.

The relatively small number of the patients and retrospective design of the study were the main limitations of this work. In addition, the lack of a control group or case controls to overcome the negative impact of the possibly confounding factors and different follow-up periods for the patients were other issues that should be taken into consideration for the evaluation of our results.

Conclusion

The present study revealed an association between higher pain catastrophizing and limited shoulder ROM. In addition, there was a complex interaction between pain catastrophizing, SP, and limited shoulder ROM. Future studies are needed to investigate pain catastrophizing as a predictive factor to reveal postoperative shoulder ROM limitation. Such a tool could be useful to stratify the patients with rehabilitation need, thereby alleviating their postoperative shoulder ROM limitation.

Statement of Ethics

Ethical committee approval for this study was obtained from the local research ethics committee registered under No. 18-KAEK-242. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the institution. All patients and/or their legal guardians provided written informed consent, and basic demographic information was collected.

Disclosure Statement

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding Sources

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Author Contributions

Ahmet Akbas: idea and concept, design, data collection and processing, analysis and interpretation.

Hasan Dagmura: literature review;

Emin Daldal: writing the article;

Fatih Mehmet Dasiran: references, analysis, and interpretation;

Hülya Deveci: analysis and interpretation;

Ismail Okan: control and supervision.

References

- 1.Merino T, Ip T, Domínguez F, Acevedo F, Medina L, Villaroel A, et al. Risk factors for loco-regional recurrence in breast cancer patients: a retrospective study. Oncotarget. 2018 Jul;9((54)):30355–62. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ibrahim M, Muanza T, Smirnow N, Sateren W, Fournier B, Kavan P, et al. A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial on the Effects of a Progressive Exercise Program on the Range of Motion and Upper Extremity Grip Strength in Young Adults With Breast Cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2018 Feb;18((1)):e55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lovelace DL, McDaniel LR, Golden D. Long-Term Effects of Breast Cancer Surgery, Treatment, and Survivor Care. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2019 Nov;64((6)):713–24. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.13012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee YM, Mak SS, Tse SM, Chan SJ. Lymphoedema care of breast cancer patients in a breast care clinic: a survey of knowledge and health practice. Support Care Cancer. 2001 Nov;9((8)):634–41. doi: 10.1007/s005200100270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang EJ, Park WB, Seo KS, Kim SW, Heo CY, Lim JY. Longitudinal change of treatment-related upper limb dysfunction and its impact on late dysfunction in breast cancer survivors: a prospective cohort study. J Surg Oncol. 2010 Jan;101((1)):84–91. doi: 10.1002/jso.21435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buyukakincak O, Akyol Y, Ozen N, et al. Breast cancer surgery: is it a problem for the upper extremity?/Meme kanseri cerrahisi: ust ekstremite icin bir problem midir? Turkish Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2013;59((4)):304–10. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Box RC, Reul-Hirche HM, Bullock-Saxton JE, Furnival CM. Shoulder movement after breast cancer surgery: results of a randomised controlled study of postoperative physiotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002 Sep;75((1)):35–50. doi: 10.1023/a:1016571204924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Groef A, Van Kampen M, Dieltjens E, Christiaens MR, Neven P, Geraerts I, et al. Effectiveness of postoperative physical therapy for upper-limb impairments after breast cancer treatment: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015 Jun;96((6)):1140–53. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morimoto T, Tamura A, Ichihara T, Minakawa T, Kuwamura Y, Miki Y, et al. Evaluation of a new rehabilitation program for postoperative patients with breast cancer. Nurs Health Sci. 2003 Dec;5((4)):275–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2018.2003.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pavlin DJ, Sullivan MJ, Freund PR, Roesen K. Catastrophizing: a risk factor for postsurgical pain. Clin J Pain. 2005 Jan-Feb;21((1)):83–90. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200501000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Süren M, Okan I, Gökbakan AM, Kaya Z, Erkorkmaz U, Arici S, et al. Factors associated with the pain catastrophizing scale and validation in a sample of the Turkish population. Turk J Med Sci. 2014;44((1)):104–8. doi: 10.3906/sag-1206-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7((4)):524–32. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osman A, Barrios FX, Kopper BA, Hauptmann W, Jones J, O'Neill E. Factor structure, reliability, and validity of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale. J Behav Med. 1997 Dec;20((6)):589–605. doi: 10.1023/a:1025570508954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Özalp G, Sarioglu R, Tuncel G, Aslan K, Kadiogullari N. Preoperative emotional states in patients with breast cancer and postoperative pain. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2003 Jan;47((1)):26–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2003.470105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suren M, Kaya Z, Gokbakan M, Okan I, Arici S, Karaman S, et al. The role of pain catastrophizing score in the prediction of venipuncture pain severity. Pain Pract. 2014 Mar;14((3)):245–51. doi: 10.1111/papr.12060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papaioannou M, Skapinakis P, Damigos D, Mavreas V, Broumas G, Palgimesi A. The role of catastrophizing in the prediction of postoperative pain. Pain Med. 2009 Nov;10((8)):1452–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wright D, Hoang M, Sofine A, Silva JP, Schwarzkopf R. Pain catastrophizing as a predictor for postoperative pain and opiate consumption in total joint arthroplasty patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2017 Dec;137((12)):1623–9. doi: 10.1007/s00402-017-2812-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kibar S, Dalyan Aras M, Ünsal Delialioğlu S. The risk factors and prevalence of upper extremity impairments and an analysis of effects of lymphoedema and other impairments on the quality of life of breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2017 Jul;26((4)):e12433. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smoot B, Paul SM, Aouizerat BE, Dunn L, Elboim C, Schmidt B, et al. Predictors of Altered Upper Extremity Function During the First Year After Breast Cancer Treatment. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2016 Sep;95((9)):639–55. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ribeiro IL, Camargo PR, Alburquerque-Sendín F, Ferrari AV, Arrais CL, Salvini TF. Three-dimensional scapular kinematics, shoulder outcome measures and quality of life following treatment for breast cancer - A case control study. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2019 Apr;40:72–9. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2019.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang Z, Huang S, Wang J, Xi Y, Yang X, Tang Q, et al. A retrospective study of lymphatic transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous/deep inferior epigastric perforator flaps for breast cancer treatment-induced upper-limb lymphoedema. Sci Rep. 2017 Mar;7((1)):80. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00164-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richmond H, Lait C, Srikesavan C, Williamson E, Moser J, Newman M, et al. PROSPER Study Group Development of an exercise intervention for the prevention of musculoskeletal shoulder problems after breast cancer treatment: the prevention of shoulder problems trial (UK PROSPER) BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 Jun;18((1)):463. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3280-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mejdahl MK, Andersen KG, Gärtner R, Kroman N, Kehlet H. Persistent pain and sensory disturbances after treatment for breast cancer: six year nationwide follow-up study. BMJ. 2013 Apr;346(apr11 1):f1865. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hidding JT, Beurskens CH, van der Wees PJ, van Laarhoven HW, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW. Treatment related impairments in arm and shoulder in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014 May;9((5)):e96748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee TS, Kilbreath SL, Refshauge KM, Herbert RD, Beith JM. Prognosis of the upper limb following surgery and radiation for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008 Jul;110((1)):19–37. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9710-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark B, Sitzia J, Harlow W. Incidence and risk of arm oedema following treatment for breast cancer: a three-year follow-up study. QJM. 2005 May;98((5)):343–8. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hci053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wanchai A, Armer JM, Stewart BR, Lasinski BB. Breast cancer-related lymphedema: A literature review for clinical practice. Int J Nurs Sci. 2016;3((2)):202–7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rietman JS, Dijkstra PU, Debreczeni R, Geertzen JH, Robinson DP, De Vries J. Impairments, disabilities and health related quality of life after treatment for breast cancer: a follow-up study 2.7 years after surgery. Disabil Rehabil. 2004 Jan;26((2)):78–84. doi: 10.1080/09638280310001629642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaya T, Karatepe AG, Günaydn R, Yetiş H, Uslu A. Disability and health-related quality of life after breast cancer surgery: relation to impairments. South Med J. 2010 Jan;103((1)):37–41. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181c38c41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lauridsen MC, Overgaard M, Overgaard J, Hessov IB, Cristiansen P. Shoulder disability and late symptoms following surgery for early breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2008;47((4)):569–75. doi: 10.1080/02841860801986627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tengrup I, Tennvall-Nittby L, Christiansson I, Laurin M. Arm morbidity after breast-conserving therapy for breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2000;39((3)):393–7. doi: 10.1080/028418600750013177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shamley D, Srinaganathan R, Oskrochi R, Lascurain-Aguirrebeña I, Sugden E. Three-dimensional scapulothoracic motion following treatment for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009 Nov;118((2)):315–22. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0240-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ernst MF, Voogd AC, Balder W, Klinkenbijl JH, Roukema JA. Early and late morbidity associated with axillary levels I-III dissection in breast cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2002 Mar;79((3)):151–5. doi: 10.1002/jso.10061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leung L. Pain catastrophizing: an updated review. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012 Jul;34((3)):204–17. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.106012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.George SZ, Wallace MR, Wright TW, Moser MW, Greenfield WH, 3rd, Sack BK, et al. Evidence for a biopsychosocial influence on shoulder pain: pain catastrophizing and catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) diplotype predict clinical pain ratings. Pain. 2008 May;136((1-2)):53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parr JJ, Borsa PA, Fillingim RB, Tillman MD, Manini TM, Gregory CM, et al. Pain-related fear and catastrophizing predict pain intensity and disability independently using an induced muscle injury model. J Pain. 2012 Apr;13((4)):370–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Eijsden-Besseling MD, van Attekum A, de Bie RA, Staal JB. Pain catastrophizing and lower physical fitness in a sample of computer screen workers with early non-specific upper limb disorders: a case-control study. Ind Health. 2010;48((6)):818–23. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.ms1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bergbom S, Boersma K, Overmeer T, Linton SJ. Relationship among pain catastrophizing, depressed mood, and outcomes across physical therapy treatments. Phys Ther. 2011 May;91((5)):754–64. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sullivan MJ, Rodgers WM, Wilson PM, Bell GJ, Murray TC, Fraser SN. An experimental investigation of the relation between catastrophizing and activity intolerance. Pain. 2002 Nov;100((1-2)):47–53. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crombez G, Vlaeyen JW, Heuts PH, Lysens R. Pain-related fear is more disabling than pain itself: evidence on the role of pain-related fear in chronic back pain disability. Pain. 1999 Mar;80((1-2)):329–39. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00229-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thibault P, Loisel P, Durand MJ, Catchlove R, Sullivan MJ. Psychological predictors of pain expression and activity intolerance in chronic pain patients. Pain. 2008 Sep;139((1)):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]