Abstract

The purpose of this study is to develop candidate common data element (CDE) items related to clinical staff training in long-term care (LTC) homes that can be used to enable international comparative research. This paper is part of the WE-THRIVE (Worldwide Elements to Harmonize Research in Long-Term Care Living Environments) group’s initiative which aims to improve international academic collaboration. We followed best practices to develop CDEs by conducting a literature review of clinical staff (i.e., Regulated Nurses, Health Care Aides) training measures, and convening a subgroup of WE-THRIVE experts to review the literature review results to develop suitable CDEs. The international expert panel discussed and critically reflected on the current knowledge gaps from the literature review results. The panel proposed three candidate CDEs which focused on the presence of and the measurement of training. These three proposed CDEs seek to facilitate international research as well as assist in policy and decision-making regarding LTC homes worldwide. This study is a critical first step to develop candidate CDE items to measure staff training internationally. Further work is required to get feedback from other researchers about the proposed CDEs, and assess the feasibility of these CDEs in high and low resourced settings.

Keywords: common data elements, training, nursing home, long-term care, measurement

As the global population ages, the spotlight is on long-term care (LTC) homes (e.g., care homes, nursing homes) to meet the needs of older adults with multiple complex and chronic conditions (Beard et al., 2016). Staff training is a widely accepted method to build staff capacity with broad-reaching benefits for residents (Alzheimers Disease International, 2013; Fujisawa & Colombo, 2009; Hussein & Manthorpe, 2005; Spector et al., 2016). Staff training involves programs (e.g., in-services and workshops) offered by the workplace that impart a set of specific skills or knowledge to improve employee performance in certain areas and settings (Davis & Lundstrom, 2011; Saponaro & Baughman, 2009). Such training augments and enhances individuals’ knowledge, understanding, behaviors, skills, values, and beliefs (Davis & Lundstrom, 2011). Training, alongside other professional development opportunities, can also improve societal perceptions of careers in LTC homes and therefore attract and retain more people to the sector (Fujisawa & Colombo, 2009; Hussein & Manthorpe, 2005).

LTC homes are defined as facilities certified within their countries to provide continuous nursing care and personal support to residents that include assistance with their activities of daily living and complex health conditions (National Institute on Ageing, 2019). This care is often provided by informal caregivers (e.g., family members) and clinical staff. The current paper will focus on clinical staff defined as staff who are formally trained and employed part- or full-time by LTC homes (e.g., Registered Nurses, Registered Practical Nurses, Licensed Practical Nurses, and Health Care Aides/Personal Support Workers/Nursing Aides) to provide direct patient care. As clinical staff provide direct patient care, inadequate workplace training can negatively impact staff’s attitudes and skills, the quality of care provided and worsen health outcomes for older people residing in LTC (Cooper et al., 2016). While preparatory education may encourage individuals to potentially seek employment in LTC, this paper is focused on supporting the clinical staff in LTC by means of on-the-job training which may be associated with staff retention, and the ability to enhance the quality of care and quality of life for residents in LTC (Caspar et al., 2016; Fujisawa & Colombo, 2009; Kane, 2003; Spector et al., 2016).

Staff Training in LTC: Challenges for International Research in LTC Homes

The provision of staff training in LTC is met with logistical and methodological challenges; first, previous research indicates that the variability of the LTC workforce, such as their professional backgrounds, cultural and sociodemographic characteristics, and educational levels, coupled with high rates of LTC staff turnover of an aging workforce in LTC, complicates the process to provide training (Fujisawa & Colombo, 2009; Hussein & Manthorpe, 2005). Second, while staff training is often prompted by the care needs of the residents in the LTC home, current training often fails to scaffold on current knowledge and inadequately addresses the knowledge, skills and competencies required (Stone & Harahan, 2010). Third, the OECD (Fujisawa & Colombo, 2009) has reported significant within and between country differences in the availability of the content, duration and emphasis on on-the-job training versus theoretical learning in training programs for LTC staff. Lastly, from a resource perspective, individual LTC homes’ access to expertise, technology, and time will also influence the number and quality of staff training opportunities.

The lack of a minimum international standard for LTC training is prohibitive to accurately compare country experiences, curricula, and requirements (Fujisawa & Colombo, 2009). Methodologically, the resultant heterogeneity with respect to the training details like frequency, content, modality of delivery (e.g., online or in-person), and evaluation, prevents the aggregation of data to build cross-national evidence about effective training in LTC. Most training initiatives have been in experimental stages in small-scale and/or did not include an evaluation component (Aylward et al., 2003; Beeber et al., 2010; Hussein & Manthorpe, 2005; Kuske et al., 2007). These previous literature reviews referred to the evidence on staff training from a variety of settings and countries to suggest that the effectiveness of training and its long-term impact on resident care remains unclear. In sum, gaps in evidence due to methodological weaknesses, differences in training content, training duration, organizational structures in LTC, and evaluation method makes it difficult to determine what common data elements (CDEs) are important to effective staff training from a cross-national perspective (Beeber et al., 2010; Hussein & Manthorpe, 2008; Kuske et al., 2007). There is a need to create a measurement infrastructure to better understand the current landscape of clinical staff training in LTC homes located in in high and low resourced LTC settings.

International LTC research is a key lever to improve international development, policy, and practice, and more broadly enable the LTC workforce to prepare for the increasingly complex care needs of residents (Corazzini et al., 2019; World Health Organization [WHO], 2011). To this end, the “Worldwide Elements To Harmonize Research In LTC Living Environments” (WE-THRIVE) international group was formed to aggregate cross-country data to support the decision making in LTC (Corazzini et al., 2019; Lepore & Corazzini, 2019). WE-THRIVE aims to identify, develop, and evaluate the effectiveness of ecologically viable CDEs to further mutual understanding and facilitate international research in four overarching domains: LTC context; workforce and staffing; person-centered care; and care outcomes (Corazzini et al., 2019). This paper is a part of a broader body of literature examining the central concepts related to “workforce and staffing” domain (Zúñiga et al., 2019, McGilton et al., 2020). An international approach with CDEs to measure staff training in LTC will facilitate comparative research focused on the role of training in supporting staff and the workforce, and contribute to an international measurement infrastructure (Lepore & Corazzini, 2019).

The purpose of this study is to develop feasible candidate CDE items related to clinical staff training in LTC that can be used to enable international comparative research. This study is a critical first step to develop a small number of candidate CDE items that are ecologically viable to measure staff training in high to low income countries.

Methods

Following the similar approaches of recently published WE-THRIVE work (McGilton et al., 2020), we followed the Best Practices for Identifying Common Data Elements identified by Redeker et al. (2015) which involved: (1) completed a literature review of staff training outcome measures; and (2) convening a group of WE-THRIVE experts to review the literature review results to develop suitable CDEs. This is an iterative process by which the expert panel is convened, and the CDEs are developed based on the evidence over the course of multiple subgroup discussions (Redeker et al., 2015). The process of developing and proposing CDEs is ideally transparent, inclusive, and involves identifying and developing CDEs by national and international experts in the field (Redeker et al., 2015). The discussion points from the expert panel will be described in the results.

Literature Review

A WE-THRIVE subcommittee group focused on the “work staff and staffing” domain advised on the broad research questions and identified search terms to include in the search strategy. A literature review was completed to gain a broad understanding and describe the state of the literature of the “on-the-job training” provided to clinical staff in LTCs around the globe, followed by utilizing expert consensus based on the findings of the literature review. Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) scoping review framework was used: (i) identifying the research questions, (ii) identifying relevant studies, (iii) study selection, (iv) extracting and charting the data, and (v) summarizing and reporting the results. The expert panel wanted to understand what the evidence to inform the development of CDEs were and asked the following questions: what are the characteristics of training provided to clinical staff in LTC home settings? What measurement tools are used to evaluate the training? Is staff training effective in influencing staff and resident outcomes?

Search strategy

An information specialist conducted a search in July 2019 in four electronic data sources: Medline, Embase, CINAHL, and HAPI. A secondary search was conducted on Google Scholar and only the first 200 results were screened. These databases were selected to cover a broad range of disciplines from various academic sources. The search was limited to peer-reviewed publications that were full-text manuscripts and published in the last 20 years in English.

The search query consisted of terms and their synonyms suggested by the expert panel and the information specialist. Clinical staff include health care workers and professionals like nurses (“Registered Nurses; Regulated Nurses; Registered Practical Nurses; Licensed Practical Nurses), aides (“Personal Support Workers, nursing aids, nursing assistants, care aids”), training (“education”), paired with terms “nursing homes” (“LTC homes; home for the aged”), and measurement (“questionnaire; survey”). Inclusion criteria included studies that quantitatively evaluated on-the-job training on any topic for clinical staff providing direct resident care in LTC home settings. Studies focusing on pre-service education were excluded because WE-THRIVE is focused on building the capacity of the workforce in LTC settings. Citations were imported into Covidence, a web-based systematic review software to remove duplicates, and to conduct the title and abstract relevance screening.

Three research assistants (RAs) with nursing backgrounds alongside the PI (CC) conducted the screening. First, the title and abstract of citations were independently screened by two reviewers, and double checked. Studies that did not meet the eligibility criteria described above were excluded. Reviewers discussed any uncertainties to resolve conflicts related to study inclusion. Next, full-text review of the studies that were deemed relevant was completed. Articles were obtained through University institutional access. For articles that could not be accessed, the corresponding author was contacted to obtain the article. An extraction form in Excel was created based on the discussions and questions from the expert panel and included: author name, publication year, journal name, manuscript type, sample size, demographics of the sample, number of homes participating, research questions or aims, format, duration, and frequency of training, and forms of evaluation of the training, research design, attributes of staff training (training topic, summary of content, type and number of trainers, evaluation measures, follow-up duration), tools used to measure the training, how training is documented, impact of training on any nurse or resident outcomes, source of training funding, and study limitations. Outcomes related to training were included to inform a baseline understanding of the effect of training programs.

Expert panel

The formation of the expert panel has been described elsewhere (Corazzini et al., 2019; Zúñiga et al., 2019). We followed the best practices for identifying and developing CDEs (Redeker et al., 2015), and group processes were established within WE-THRIVE including forming a subgroup focused on the “workforce and staffing” domain comprised of colleague experts from Canada, USA, Switzerland, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. The subgroup held regular quarterly meetings throughout 2019 and 2020 to discuss the staff training literature review search parameters which informed the extraction form described above. Subsequently, the results of the review were discussed with the intention of determining the basic data elements related to staff training that would be applicable and inclusive of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Results

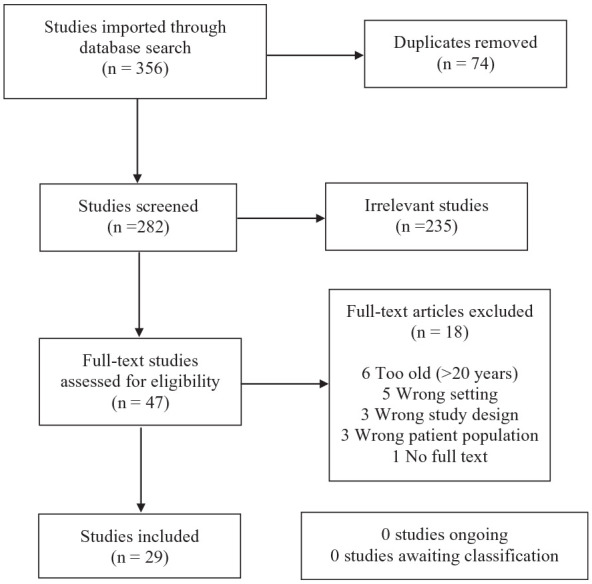

The search generated 356 manuscripts for screening, and after duplicates were removed, 282 manuscripts were left to be screened. Only 47 met the eligibility criteria for full-text screening based on the abstracts. During the full screen, articles that were not relevant were removed (Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram). Twenty-nine studies were included in the scoping review. Table 1 outlines the study characteristics such as study design, number of sites, analysis methods, and effectiveness of training on outcomes. All the included studies were from high-income countries. Most studies occurred in a single LTC home, or in multiple LTC homes in the same geographical region. The total sample size across all 29 studies included 4,933 staff participants (range = 4–1,076). Nursing Assistants (NAs) were the most common type of learners in 20 of the studies (68.97%) followed by Registered Nurses (RNs) who were involved in 13 of the studies (44.83%).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for article selection.

Table 1.

Summary of Literature Review Findings.

| Authors (country) | Type | NHs (#) | Learner | N (Female %) | Aim | Topic | Pre and post measurement | Analysis | Staff outcomes | Patient outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arco and Du Toit (2006) (Australia) | Mixed Methods; Multiple baseline | 1 | NAs | Staff: 4 (100) | To examine effects of on-the job feedback after staff training and to verify prior findings that competence was maintained after on-the-job feedback was ceased | Behavior modification | Observations Mon-Fri for 26 weeks. Baseline: observations up to 90 minutes. Over course of study: decreased to <60 minutes | Sum of resident behavior and consequences. Social validation questionnaire | Increased ability to cope with resident behaviors; increased competency | Increased positive behaviors |

| Resident: 1 (100) | ||||||||||

| Ballard et al. (2018) (U.K.) | RCT | 69 | Care staff | Residents: 553 (70.71) | To evaluate the efficacy of a PCC and psychosocial intervention on QoL, agitation, and antipsychotic use in people with dementia living in NHs and to determine its cost | Resident QoL and behavior | Baseline and at 9 months | ANCOVA | Increase in positive care interactions (p = .003) | Increase in QoL (p = .0042), improvement in agitation (p = .0076), and neuropsychiatric symptoms (p < .001) in residents with moderately severe dementia. No reduction in antipsychotic usage, global deterioration, unmet needs, pain, or mood |

| Bökberg et al. (2019) (Sweden) | Pre- and post-test experimental design | 20 | Assistant nurse, RNs, OTs, PTs, frontline managers | Staff: 365 (94.79) | To assess whether an educational intervention can effect staff perception of providing PCC for palliative persons in NHs | PCC | T = 0 and 3 months after intervention (9 months from T = 0) | Within-group comparisons, Wilcoxon signed rank test, subgroup analyses within the intervention group, Pearson χ² test or Fisher’s exact test, Mann-Whitney U-test, Kruskal-Wallis test, and a univariate logistic regression analysis | No improvement on any of the subscales and measures | – |

| Burgio et al. (2001) (U.S.A) | Mixed methods experimental design | 5 | NAs | Staff: 64 (84.38) | To examine communication skills training and use of memory books in improving communication between NAs and residents | Communication | Baseline, after intervention | ANOVA; ANCOVAs | Increased knowledge (p < .05); improved communication skills (p < .05); increased amount of positive statements to resident (p < .05); increased verbal interaction with residents (p = .02); no change in amount of time spent with resident; maintenance at 2 months f/u | Increased positive interactions (p = .01); increased independence in self-care (p = .04); no change in coherent verbal interactions |

| Residents: 67 (74.63) | ||||||||||

| Burgio et al. (2002) (U.S.A) | RCT | 2 | NAs | Staff: 85 (91.56) | To evaluate a behavior management skills training program for improving NA behavioral skill performance and any resulting effects on residents’ behaviors | Behavior management | Baseline, immediately after and 3 and 6 months after intervention | Cronbach’s α, ANOVA, ANCOVA | Increased knowledge (p < .001); decreased ineffective behavioral management techniques (p < .05), not maintained at f/u; improvement in six out of seven measured communication skills (p < .05), maintained at f/u (p < .05) | Decrease in agitation (p < .05) maintained at f/u |

| Residents: 79 (61.00) | ||||||||||

| Chang et al. (2006) (Taiwan) | Quasi-experimental | 2 | NAs | Staff: 67 (97.01) | To observe the feeding behaviors of NAs after implementation of a feeding skills training program | Feeding skills | Immediately before and after training program, and 4 weeks later | Cronbach’s α, ANOVA, ANCOVA | Increased knowledge (p < .001). No change in attitude or perceived behavior control. Increased intention frequency (p < .05) although no change in intention belief | – |

| Residents: 36 (N/A) | ||||||||||

| Crogan and Evans (2001) (U.S.A) | Pre- and post-test experimental | 1 | NAs | Staff: 20 (N/A) | To measure NAs’ knowledge of nutritional care | Nutritional care | Before and after training | Performance observation | No statistical difference between pre and posttest scores. No improvement in essential principles of care. Improvement in 10 problematic areas while problems persisted in all other areas. | – |

| Dassel et al. (2020) (U.S.A) | Pre- and post-test experimental design | 20 | RNs, NAs, OTs, informal caregivers, students, admin, faculty | Staff: 94 (81.90) | To improve the care of residents with ADRD through community-based education for interprofessional team members | Dementia | Before and after training | Paired t-tests, Cronbach’s alpha | Increased knowledge (p < .01); satisfaction with relevance and applicability of training to practice | – |

| Ghandehari et al. (2013) (Canada) | Mixed methods experimental | Two large health regions | Nurses, special care aides | Staff: 131 (N/A) | To examine a pain assessment/management PE program aimed at improving staff beliefs, attitudes, and overall knowledge | Pain assessment and management | 2 weeks before PE, after three educational sessions and 2 weeks after completion of PE | χ² tests, ANOVA, Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) tests, QSR NVivo, thematic analysis comprised the framework for examining the data | Increased knowledge (p < .001) and improved pain beliefs (p < .009) | – |

| Greene et al. (2018) (U.K) | Pre- and post-test experimental design | 2 | HCAs, RNs, catering or domestic staff, activity co-ordinators, PTs, OTs, and management | Staff: 161 (N/A) | To design, deliver and evaluate a hydration training session for care home staff that developed their knowledge and skills | Hydration | Before and after training | Wilcoxon signed-rank test of evaluation form. Qualitative data (field notes) | Increased knowledge re: dehydration (p = .000). | – |

| Huang and Wu (2008) (Taiwan) | Pre- and post-test experimental | 3 | NAs | Staff: 40 (100) | To test a hand-hygiene intervention for NAs in LTC on outcomes for NAs (knowledge, behavior) and residents (infection rate) | Hand hygiene | Before (pre-test), 1 month after (post-test I), and 3 months after (post-test II) training. Last self-report collected at 3 months post training. Behavior observed for 30 minutes during one 8 hours shift at pretest and post-test II | Descriptive statistics (means, SDs, frequencies, and percentages), paired t-test, McNemar test, χ²-test, and logistic regression test | Increased knowledge of hand hygiene (p < .001); NAs with more years of education were more likely to improve their knowledge. Increased rates of hand hygiene (p < .001). | Reduced infection rate (p < .001) |

| Huizing et al. (2006) (Netherlands) | Cluster RCT | 1 | Nurses | Residents:144 (71.53) | To investigate an educational intervention and its effect on the use of physical restraints in psycho-geriatric NH residents | Physical restraints | Baseline and 1 month post-intervention | Frequency tables, means, χ² test, t-test, Fisher’s exact test, McNemar tests, and gain scores, logistic regression analysis | No change in use, intensity, number or types of restraints used. No change in time of day when restraint used. | Decreased risk of restraint use. Increased depression. Decreased cognitive status |

| Janssens et al. (2016) (Belgium) | Cluster RCT | 12 | Nurses and NAs | Staff: 259 (95) | To explore the impact of an oral healthcare protocol, in addition to education, on nurses’ and NAs oral health-related knowledge and attitude | Oral health and hygiene | Baseline and 6 months after the start of the study | Bivariate analyzes, nonparametric tests, Mann–Whitney U-test, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test, linear mixed-model analyzes, post hoc power calculation | Increased knowledge (p < .0001), no change in attitudes; nurses demonstrated more knowledge although less favorable attitude versus NAs. Overall better attitude on psychogeriatric ward versus mixed ward | – |

| Jones et al. (2004) (U.S.A) | Mixed methods experimental | 12 | 25% RN, 26%. LPN, and 49% PSW | Staff: 628 (N/A) | To develop a culturally competent intervention to improve NH pain practices, improve staff knowledge and attitudes about pain, improve pain practices in NHs and improve NH pain policies and procedures | Pain | Staff: before and after training. Residents: quarterly (before, during and after) | ANOVAs, GLMs, GEEs, χ² tests, focus groups, interviews, observations | Subtle increase in knowledge and attitudes. Decline in perceived barriers | Decreased reports of constant pain (p < .001). Improved pain reassessments (p < .05) No difference in overall pain reporting and acute moderate/severe pain. |

| Residents: 1,899 (N/A) | ||||||||||

| Kemeny et al. (2006) (U.S.A) | Multiple baseline | 1 | NAs and nurses | Staff: 77 (92) | To describe experiential techniques used by Project RELATE in training for PCC, and NAs’ and nurses’ response | PCC | After each session and 2 months after | Likert scale; percent correct; effect size, d-scores | Favorable reactions to implement training in practice (p < .05); NAs reported more favorable reactions versus nurses. Increased knowledge (more so in nurses vs. NAs) (p < .05). Retention of knowledge 2 months later (p < .05). Increased confidence | – |

| Leone et al. (2013) (France) | Mixed methods experimental | 16 | Psychologists, physicians, nurses, practical nurses, agent of hospital service | Staff: 563 (N/A) | To evaluate the effectiveness of staff education for the management of apathy in older adults with dementia | Apathy | Baseline, at the end of the training program (week 4) and 3 months later (week 17) | Quantitative evaluation: change in AI–C scores, NPI–NH, Katz ADL Scale and on the two observation scales, mean comparisons using t-test; χ² test; multiple linear regression analysis | Improved knowledge although not significant | Improvements in emotional blunting (p < .01). More self-sufficient in “dressing” and “transferring” (p < .05) on Katz ADL Scores. Increase in affective and psychotic symptoms (p < .01). No change in number of drugs prescribed |

| Residents: 230 (79.5) | ||||||||||

| Mackenzie and Peragine (2003) (Canada) | Quasi-experimental | 1 | RNs, RPNs, HCAs, privately paid caregiver | Staff: 41 (92.68) | To describe the development and outcome of a stress and burnout relieving intervention by enhancing self-efficacy in managing challenging teams, residents, and family situations. Secondary purpose is to present a self-efficacy inventory to measure the effectiveness of the intervention | Managing stress and self-efficacy | Before, immediately after, and 3 months after | t-test and χ² analyzes; ANCOVAs | Similar knowledge between groups at post-test; at 3 months f/u INT group had increased knowledge (p < .01). Increased self-efficacy (p < .01). Increased feelings of personal accomplishment (p < .05) not maintained at f/u | – |

| Magai et al. (2002) (U.S.A) | RCT | 3 | Nursing staff | Staff: 20 (100) | To assess a nonverbal sensitivity training program on the care provided to dementia patients and on staff caregiver well-being | Nonverbal communication | Baseline and 4 × 3 week intervals | Repeated measures ANOVAs, Wilks’s lambda | Improved affective state; improved BSI scores (p < .01) | Increased positive affect (p < .05), which converged with control groups at f/u |

| Residents: 91 (93) | ||||||||||

| McAiney et al. (2007) (Canada) | Pre- and post-test experimental | 439 | RNs, RPNs, SWs, and other health disciples | Staff: 1,076 (N/A) | To describe an education program for the management of mental health problems in LTC and the evaluation of its impact and sustainability | Mental health | Before start of program, and 6 weeks after | Frequencies, percentages, ranges, means, standard deviations, paired t-tests | Increased confidence (p < .001), understanding and assessment of mental health problems (p < .01). Increased confidence and use of assessment tools (p < .01) | – |

| Peterson et al. (2002) (U.S.A) | Pre- and post-test experimental | 6 | NAs, LPNs, RNs, SW, admins, music therapist, porter | Staff: 72 (93.1) | To evaluate the effect of an educational course on dementia on staff knowledge, stress, and self-esteem | Dementia | Baseline, immediately after and 6 to 8 weeks after training | Pearson correlation, General Linear Model, Cramer’s V | Increased knowledge in all groups, although only significant in those with prior training (p = .004; no significant change in stress or self-esteem scores | – |

| Peterson et al. (2004) (U.S.A) | Pre- and post-test experimental | 1 | NAs, RNs, LPNs | Staff: 35 (N/A) | To develop an ergonomics training program for selected NAs at a state-run veterans’ home to decrease musculoskeletal disorders | Ergonomics | 3 months before training, at the end of the training program and 1 month after training | Two-paired student’s t-test; ANOVA | Increased knowledge (p < .001). No change in level of stress for risk factors, pain or discomfort, or perceived general health | – |

| Resnick et al. (2009) (U.S.A) | RCT | 12 | NAs | Staff: 523 (93) | To describe the implementation process of the educational component of the restorative care intervention, the outcomes and the effect on NA knowledge | Restorative care | Baseline and immediately after intervention | (SD = 2.7, F = 280.4, p < .05) | Increased knowledge re: restorative care (p < .05) | – |

| Rosen et al. (2002) (U.S.A) | RCT | 3 | RNs, LPNs and NAs | Staff: 279 (N/A) | To design and assess a curriculum of staff training on depression and dementia | Depression/dementia | Before each training session and after final session | χ² test; Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test; Mann-Whitney (M-W) tests; Wilcoxon rank sum test, ANOVA, posthoc pair-wise comparisons | Increased knowledge in all sites but significant in computer site (p < .005) | – |

| Scerri and Scerri (2019) (Malta) | Pre- and post-test experimental | – | Nursing offices, deputy charge nurses, staff nurses, and enrolled nurses | Staff: 214 (68.2) | To investigate a dementia training program on nursing staff working in public nursing/residential homes on their knowledge, attitudes, and confidence | Dementia | Beginning of the first session and the end of the last session | Shapiro-Wilk test, independent sample t-test, ANOVA, post-hoc Tukey’s test, Pearson correlation test, Pearson Chi-square, Cohen’s d, stepwise regression analysis | Increased knowledge (p < .001). Improved staff attitude (p = .001). Increased confidence (p = .017). Training found to have a cumulative effect | – |

| Smith et al. (2013) (U.S.A) | Mixed methods experimental | 13 | RNs and LPNs | Staff: 24 (N/A) | To describe a CD-based depression training program and its use and feasibility of nurses using it with older adults in their care, and to evaluate training-related outcomes among those residents | Depression | Baseline and at 8, 12, and 16 weeks | t-tests and χ² analyzes, linear mixed modeling, non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test | No difference between groups in method of training. Improved knowledge, care and outcomes | Improved depression scores from baseline to f/u (p < .001). Decreased pain in all groups (p = .006); f/u tests suggests that only usual care group pain improved significantly (p < .01). No improvement in QoL or anxiety scores |

| Residents:50 (76) | ||||||||||

| Soderlund et al. (2014) (Sweden) | Mixed methods experimental | 1 | RNs, LPNs, NAs | Staff: 12 (100) | To explore nurses’ experiences of attending a VM training program and to describe ratings of the work climate among the entire nursing staff | Communication style | Before and after intervention | Descriptive statistics | Difficulty changing communication style. Increased self-reflection. Increased positive interactions. Increased confidence. Improved work environment | – |

| Williams et al. (2016) (U.S.A) | Pre- and post-test experimental | 2 | CNAs, LPNs, RNs | Staff:26 (88.46) | To facilitate the implementation of oral health protocols in NHs | Oral health | 3 months before and 3 months after intervention. Retrospective chart review 1/month with the intervention for 3 months | Likert survey, Cronbach’s α test, Wilcoxon signed rank test, McNemar’s test | Increased feelings of responsibility on resident to make referral (p = .02). Increased confidence in performing oral assessments (p = .009) and identifying oral conditions that need referrals (p = .03) | Increased dental referrals (p = .0018) |

| Residents:176 (N/A) | ||||||||||

| Wils et al. (2017) (Belgium) | Mixed methods experimental | 1 | Nursing staff | Staff: 13 (84.62) | To assess the effect of an education program on the registration of care goals in a NH with dementia residents and to explore the views of staff on advance care planning | ACP | Baseline and 12 months | ANOVA, F-statistic | Increased communication regarding ACP with resident and appointed representative (p < .02). Increased care goal planning (p = .05) | Increased conversations about ACP (p = .00) |

| Residents: 124 (72.58) | ||||||||||

| Yasuda and Sakakibara (2017) (Japan) | One group repeated measures | 1 | Care staff | Staff: 40 (N/A) | To determine how educational intervention for care staff can help to improve the status of residents with dementia | Dementia | Baseline, 1 month later and after intervention | Wilcoxon signed-rank test, DCM data processing, ME value | – | Increased WIB values (p < .001). Increased social interactions in DCM (p = .041) |

| Residents: 40 (77.5) |

Note. Abbreviations used based on order of appearance: NH = nursing home; NA = nursing assistant; RCT = randomized control trial; PCC = person centered care; QoL = quality of life; RN = registered nurse; OT = occupational therapist; PT = physical therapist; ADRD = Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias; PE = pain education; HCA = healthcare aide; LTC = long term care; LPN = licensed practical nurse; PSW = personal support worker; AI-C = Apathy Inventory–Clinician version; NPI-NH = neuropsychiatric inventory-nursing home version; ADL = activities of daily living; SW = social worker; CTN = control group; INT = intervention group; ACP = advanced care planning; DCM = dementia care mapping; ME value = mood and engagement value; WIB = well-being and ill-being.

Characteristics of the Staff Training

Table 2 presents the training content, components, formats, duration, funding source, evaluation measures, and instructor. The most commonly taught topic involved dementia care (n = 16) including topics such as caring for residents with dementia through QoL and person-centered care (PCC) training (Ballard et al., 2018; Kemeny et al., 2006), managing apathy and depression in residents with dementia (Leone et al., 2013; Rosen et al., 2002), communication and behavior management with residents with dementia (Burgio et al., 2001, 2002; Magai et al., 2002), nutrition in dementia residents (Chang et al., 2006), restraint use on dementia residents (Huizing et al., 2006), self-efficacy training to prevent staff burnout related to caring for residents with dementia (Mackenzie & Peragine, 2003), pain practices and beliefs in dementia care (Ghandehari et al., 2013) and engaging in advanced care planning (ACP) related conversations with dementia residents (Wils et al., 2017). Two studies each provided training about oral care (Janssens et al., 2016; Williams et al., 2016), nutrition (Crogan & Evans, 2001; Greene et al., 2018), and depression and mental health (McAiney et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2013). Remaining training topics were: communication styles with residents (Soderlund et al., 2014), ergonomics (Peterson et al., 2004), pain management (Jones et al., 2004), staff hand hygiene (Huang & Wu, 2008), PCC (Bökberg et al., 2019), restorative care (Resnick et al., 2009), and behavioral modification (Arco & Du Toit, 2006).

Table 2.

Summary of Training.

| Author | Format of training | Components of training | Quantitative measure | Psychometric properties | Duration of training (hour) | Content | Funder | Instructor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arco and Du Toit (2006) | Workshops | Training, observation, feedback | Social validation questionnaire, observational coding | Interobserver agreement during observational coding | 2 hours/week for 3 weeks | Changes associated with aging and how institutional living and relations with staff affect behavior. Behavioral management principles were described. Behavior support plan | Australian Commonwealth Government | First author (clinical psychologist) and and second author (postgraduate student) |

| Ballard et al. (2018) | Interview, lecture, experiential learning, and application in NH | Training, medication review, cost analysis | CDR, FAST, DEMQOL-Proxy, CMAI, NPI-NH, CSDD, CANE, adapted version of the CSRI, Quality of Interactions Scale, Abbey Pain Scale | Reliable and valid as per previous studies (refer to references for each instrument) | 2 days or four half-days for 1 month. After, 6 hours/month for 4 months. Finally, 8 hours/month for 4 months | Person-centered activities and social interactions. Review of antipsychotic medications | National Institute of Health Research | Research therapist. Two lead care staff members (WHELD champions) |

| Bökberg et al. (2019) | Educational seminars | Training only | P-CAT, PCQ-S | This version of the P-CAT and PCQ-S is reported to be valid, reliable, and applicable for continued use | Five 2-hour seminars over 6 months | Key principles of palliative care and clinical practice guidelines (both based on the WHO definition of palliative care) | Swedish Research Council; the Vårdal Foundation; the Gyllenstierna Krapperup’s Foundation; Medical Faculty, Lund University; the City of Lund; Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, Linnaeus University; the Greta and Johan Kock Foundation, and the Ribbingska Memorial Foundation | Palliative and geriatric RNs and researchers |

| Burgio et al. (2001) | Didactic training, role play, case studies, group discussions | Training, chart review, environment assessment | CNA Communication Skills Checklist, CABOS, MMSE, (FIM)—REACH Version | Validated tools supported by previous research | 3 hours (additional hour for supervisors) over 1 week, followed by hands-on training for 4 weeks | Memory books and general communication skills; staff motivational system | The National Institute on Aging | Project manager (licensed clinical psychologist) |

| Burgio et al. (2002) | In-service classes, hands-on training, case studies, videos, group discussion, workbooks | Training, medical records review, family interview | MMSE, The Barthel Self-Care Rating Scale, CDR, CMAI, the Behavior Management Skills Checklist, computer-assisted behavioral observation systems | Validated tools supported by previous research | 5 hours over three consecutive days followed by hands-on training for 2 weeks | Factors in environment that can affect resident behavior, communication skills and behavior management techniques | The National Institute of Nursing Research | Geropsychologist from the research staff |

| Chang et al. (2006) | In-service classes and hands-on training | Training only | Formal Caregivers’ Knowledge of Feeding Dementia Patients Questionnaire, the Formal Caregivers’ Attitude toward Feeding Dementia Patients Questionnaire, the Perceived Behavior Control Scale, the Intention Scale, the Formal Caregivers’ Behaviors in Feeding Dementia Patients Observation Checklist | Comprehensive literature review, clinical experience, and observations were used to create the questionnaires. | 4 hours over two consecutive days | Overview of dementia, common eating behaviors and protocol for managing feeding problems associated with dementia patients. | – | The PI (RN, PhD) |

| Reviewed by a gerontological nursing expert. | ||||||||

| Internal consistency supported by Cronbach’s alpha for all instruments. | ||||||||

| Content validity verified by experts in psychology and nursing | ||||||||

| Crogan and Evans (2001) | Discussion, audiovisual presentations, experiential exercises, and role-playing | Training only | Multiple choice pre/post-test | – | 4 hours | Cues to feeding procedures and nutritional aspects of caring for resident; teaching plan, student notetaking guide, handouts, and a pocket guide | – | A skilled gerontological nurse |

| Dassel et al. (2020) | Audio-visual recorded presentations, case study, and supplemental information | Training only | Modified ADKS | Approx 3 hours online module | Overview of dementia, understanding behaviors and approach, effective communication | Health Resources and Services Administration | Faculty members and clinicians at the University of Utah | |

| Ghandehari et al. (2013) | Focus group sessions, seminars with discussion, participation and critical thinking | Training, focus groups | PKBQ, Modified Pain Beliefs Questionnaire, session content knowledge test | The PKBQ has been previously found to be valid and internally consistent (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78) | 3 hours/weeks for 3 weeks (total 9 hours) | Assessing and managing pain in LTC based on empirical evidence (pharmacological and nonpharmacological); nutrition; physical functioning/physical activity; individual-centered care | Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation; Canadian Institutes of Health Research | Experts in pain management |

| The Modified PBQ has been previously found to have criterion validity, concurrent validity, and satisfactory reliability. | ||||||||

| Greene et al. (2018) | Emotional mapping, hydration quiz, case studies, hands-on-activity | Training, observations | Self-developed questionnaires | – | 2 hours | Fluid preferences, s/s of dehydration + treatment, hydration principles | The National Institute for Health Research | Two staff from project team |

| Huang and Wu (2008) | In-service classes + hands-on training, motivating and giving feedback to NAs, engineering controls and placing reminders in the workplace | Training, infection rates | Hand-Hygiene Questionnaire, Behavior toward the Hand-Hygiene Observation Checklist | Comprehensive literature review, clinical experience and observations used to develop the instruments. | – | Purpose of intervention, overview of infection in NH residents, etiology and importance of hand hygiene, and timing and protocol for hand hygiene. | Chung Gung Medical Research Foundation | The two authors affiliated with Chang Gung University, and Zhong-Xian Hospital in Taiwan |

| Cronbach’s alpha for Hand Hygiene Questionnaire = 0.76. | ||||||||

| 92% inter-rater reliability reached for the checklist. Cronbach’s alpha for the checklist = 0.85 | ||||||||

| Huizing et al. (2006) | Small-scale meetings with an active learning environment and consultation with a nurse specialist | Training, restraint use observation | MDS CPS, MDS ADL Self-performance Hierarchy, the DRS, the Social Engagement Scale, a mobility scale, accident registration form | CPS scale corresponds with the MMSE and the Test for Severe Impairment | Five meetings of 2 hours, followed by a 1.5 hour session, over 2 months | Philosophy of restraint-free care and techniques of individualized care; decision-making process towards restraint use, effects and consequences of restraint use, strategies to analyze risk behavior of residents and alternatives for restraints; discussion of real-life cases | MeanderGroep Zuid-Limburg, the Provincial Council for the Public Health (Limburg) and Maastricht University | Nurse specialized in restraints |

| The internal consistency of the mobility scale was high (Cronbach’s α = 0.97). | ||||||||

| The reliability and validity of the scales were found to be sufficient from other studies | ||||||||

| Janssens et al. (2016) | Three educational stages; oral presentation/lecture; practical education; oral healthcare record keeping; supervised implementation; train-the-trainer concept | Training only | Oral healthcare questionnaire | Content and construct validity reviwed by experts in the field of gerotonlogy. | Initial 1.5 hour presentation, followed by 2 hours lecture + 1 hourpractical component, and finally a 1.5 hour theoretical + practical session | Theoretical and practical essentials of the guideline; summary of the guideline and all oral hygiene actions, such as tooth brushing | – | Project supervisor, at least two Ward Oral healthcare Organizers (nurses or NAs) per ward, a coordinating physician and optionally an occupational and/or speech therapist; the second author was also involved in supervised implementation; fourth author (dental hygenist) provided support |

| Jones et al. (2004) | Interactive educational sessions; case studies; videos | Training, pain assessments, medical record review | Staff pain surveys, modified Quick Pain Assessment | Internal consistency reliabilities and Cronbach’s α reliability was adequate for the surveys | 4 × 30minutes sessions over 6 months | Pain problem and assessment; pharmacologic management; communication issues; pain case studies | Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to the School of Nursing, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center | The first author |

| Kemeny et al. (2006) | Didactic sessions; coaching sessions; role play; simulations; debriefing | Training only | General reaction question scales, training evaluation | Face validity was reviewed by the researchers. Cronbach’s alphas ranged from 0.89 to 0.97 for each instrument. | – | Dementia; PCC; communication skills | Blodgett Butterworth Health Care Foundation | – |

| Leone et al. (2013) | Didactic session; interactive, hands-on teaching | Training only | Katz ADL Scale, NPI-NH, the Apathy Inventory–Clinician version, a Group Observation Scale, an Individual Observation Scale | Katz ADL Scale: valid and predictive | Initially 2 hours, followed by 4 hours/weeks for a month | AD and BPSD; apathy and depression s/s and practical advice and methods to counteract; techniques for dealing with deficits in ADLs; nonpharmacological interventions | Fondation de Coopération Scientifique and the ARMEP association | Two psychologists |

| Norwegian version of NPI-NH found to be reliable and valid | ||||||||

| Mackenzie and Peragine (2003) | Didactic information and discussion; experiential role-play | Training only | The Inventory of Geriatric Nursing Self-Efficacy, knowledge questionnaire, 22-item MBI28, the Organizational Job Satisfaction Scale | Self-efficacy scale: Cronbach’s alpha = 0.96, average item-total correlation = 0.83. | 4 × 2hours modules (one session/week for 1 month) | Teamwork module; challenging behavior module; family module; review module | Morris Slivka Fellowship | – |

| Knowledge questionnaire: Internal consistency = 0.78. | ||||||||

| Previous literature supports the reliability and validity of the MBI as the gold standard for measuring The MBI is the gold standard for measuring burnout | ||||||||

| Magai et al. (2002) | Didactic/experiential sessions, videos, hands-on training | Training, caregiver interviews, behavior and facial expression assessment | BEHAVE-AD, CMAI, CDS, BSI, the Adult Developmental Interview | Internal consistency reliabilities for all measurement scales is high (alpha > 0.69) | 10 × 1-hour sessions over 2 weeks | Issues of nonverbal communication and emotion expression; cognitive and behavioral aspects of dementia | – | Clinical psychologist |

| McAiney et al. (2007) | Peer mentoring and coaching; homework assignments; case-based; small group work; minimum lecture time | Training, long-term sustainability review | Pre/post-test questionnaires | Face and content validity of the measures ensured through reflecting material from the education program as well as receiving input from clinical experts. Cronbach’s α = 0.74 | 18 hours over 3 days followed by 12 hours over 2 days | OA physical and cognitive/mental health problems and behaviors; ADRD | MOHLTC | Clinicians and group facilitators |

| Peterson et al. (2002) | Didactic session, videos, role play, sensitization exercises, interactive discussion | Training only | Dementia Quiz, FCSI, Ownership subscale of the Reciprocal Empowerment Scale | Reliability of tools were high (alpha > 0.79) and face, concurrent, and predictive validity acceptable | 6 hours class | Physiology of dementia, coping with challenging behaviors, performing ADLs | Emmett J. and Mary Martha Doerr Center for Social Justice Education and Research in the School of Social Service at Saint Louis University | Professional educators with CNA or RN experience |

| Peterson et al. (2004) | Didactic session; floor supervision | Training, work environment review | Pre/post-test questionnaires | – | – | Top 20 perceived risk factors; correct ergonomic work practices; administrative strategies; use of engineering controls. | – | Research assistant |

| Resnick et al. (2009) | Educational sessions, group discussion, individual instruction, role play, case studies | Training only | The Theoretical Testing of Restorative Care Nursing | Evidence of test-retest reliability and validity based on prior use (Resnick et al., 2009) | 30 minutes/weeks for 6 weeks | Intro to restorative care, resident motivation, specific skills associated with restorative care, documenting restorative care activities, overcoming challenges to implementation | Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Grant | Advanced practice nurse |

| Rosen et al. (2002) | Computer-based interactive video training; lecture; individual, self-paced training | Training only | Satisfaction/relevance questionnaire, pre/post-training test | – | 12 modules of 35 to 45 minutes (CS); 30 to 45 minutes/month for 6 months (LS) | Mental health in aging, depression, and dementia; changes associated with aging; behavior + nonpharmacological interventions; AD (and other dementias); behavior management; fundamentals of agitation and aggression | National Institute on Aging and National Institute of Mental Health | Computer (CS); advanced degree nurse (LS) |

| Scerri and Scerri (2019) | Didactic session; discussions | Training only | ADKS, DAS, Confidence in Dementia Scale | ADKS: has adequate reliability and content, predictive, concurrent, and convergent validity. | 7 × 2 hours sessions (14 hours total) | Into to dementia care and services; activities for dementia OA; dementia-friendly design and assistive technologies; policy and development | European Social Fund | Local experts in dementia and old age mental health |

| DAS: adequate reliability and convergent validity compared to similar instruments | ||||||||

| Smith et al. (2013) | CD-based training; psychiatric nurse enhanced; digitized presentation; handouts; work place exercise; case-based learning | Training, feasibility review, chart review | Self-report measure, DTPE, PHQ-9, GAD-7, IPT | Established psychometric properties; tools commonly used in geriatric research | 4-part training completed in 4 to 6 weeks | Depression and comorbid conditions; standardized rating scales; interventions; communication and teamwork | Wellmark Foundation of Iowa; Iowa Geriatric Education Center; American Psychiatric Nurses Foundation; Hartford Center of Geriatric Nursing Excellence | Computer (CD); psychiatric nurse (PDE) |

| Soderlund et al. (2014) | Group of 10 to 12 nurses; didactic session; practical training; videotape; written reflections; written test | Training, feedback | Creative climate questionnaire | Previously found to have good validity, reliability and internal consistency | 1-year program of 10 days of theoretical training/month; practical training 2-3×/week | Confirmatory, empathetic approach; verbal and non-verbal VM techniques for communication | Ersta Skondal University College; Swedish Order of St. John; Alzheimer Foundation; Dementia Association | External certified supervisor |

| Williams et al. (2016) | Chart review; didactic session; decision tree | Training, chart review | Pre and post-training survey | Acceptable internal consistency for survey items (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.709) | – | Oral assessment technique; common oral conditions and abnormalities | – | PI (RDH, MSDH) |

| Wils et al. (2017) | Didactic session; role play; workplace application; debriefing; videos | Training, debriefing, chart review | Recording of ACP in the patient file | – | 6 × 2 hours | Legal and ethical issues; communication skills | – | Law expert; one of the researchers |

| Yasuda and Sakakibara (2017) | Didactic sessions; group discussions | Training only | MMSE, Barthel Index, DCM | MMSE | 3 × 60-90 minutes | Dementia basics; PCC; communication and interactions; behaviors | – | The authors |

| Barthel Index: commonly used tool | ||||||||

| DCM: reliability and content reported by Brooker and Sure (2006) |

Note. Abbreviations used based on order of appearance: CDR = clinical dementia rating; FAST = functional assessment staging tool; CMAI = Cohen-Mansfield agitation inventory; CSDD/CDS = cornell scale for depression in dementia; CANE = camberwell assessment of need for the elderly; CSRI = client service receipt inventory; QUIS = quality of interaction scale; NIHR = national institute of health research; WHELD = well-being and health for people with dementia; P-CAT = person centered care assessment tool; PCQ-S = person centered climate questionnaire; WHO = world health organization; CNA CSC = certified nursing assistant communications skills checklist; CABOS = computer-assisted behavioral observation system; MMSE = mini-mental state exam; FIM-REACH = functional independence measure-resources for enhancing Alzheimer’s caregiver health version; NIA = national institute on aging; PI = principal investigator; ADKS = Alzheimer’s disease knowledge scale; PKBQ = pain knowledge and beliefs questionnaire; PBQ = pain beliefs questionnaire; MDS = minimum data set; CPS = cognitive performance scale; DRS = depression rating scale; GOS = group observation scale; IOS = individual observation scale; BPSD = behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia; AD = Alzheimer’s disease; MBI = Maslach Burnout inventory; BEHAVE-AD = behavioral pathology in Alzheimer’s disease rating scale; BSI = brief symptom inventory; MOHLTC = ministry of health and long term care; FCSI = formal caregiver stress index; RA = research assistant; APN = advanced practice nurse; CS = computer site; LS = lecture site; DAS = dementia attitudes scale; OA = older adult; PHQ-9 = patient health questionnaire; 3MS = modified mini-mental state exam; PNE = psychiatric nurse enhanced; VM = validation method; RDH = registered dental hygienist; MSDH = masters of science in dental hygiene; NINR = national institute of nursing research; BMSC = behavior management skills checklist; SHRF= saskatchewan health research foundation; CIHR = Canadian institutes of health research; HRSA = health resources and services administration; SES = the social engagement scale; FCS = Fondation de Coopération Scientifique; RES = reciprocal empowerment scale; NIMH = national institute of mental health; NIA = national institute on aging; CODE = confidence in dementia scale; APNA = American psychiatric nurses foundation; IGEC = Iowa geriatric education center; NHCGNE = National hartford center of geriatric nursing excellence; CCQ = creative climate questionnaire; AHRQ = agency for healthcare research and quality.

Training program duration ranged from a single 2-hour session to a full year’s intervention and follow-up. The most common format was didactic in-person educational sessions in the LTC home. The most common type of trainer were the authors of the studies, with a majority holding clinical psychology titles and/or nurse researchers.

Measurement Tools Used in Staff Training Studies

Table 2 presents all the measurement tools included in the review. Overall, studies used validated, non-validated, or a combination, to measure the effectiveness of training with a lack of consistency of measurement tools between the studies. For example, each of the 16 studies that provided dementia training used a unique combination of tools to measure resident outcomes, and while the majority of studies used validated scales including dementia severity (e.g., Clinical Dementia Rating [Morris, 1997]), behaviors (e.g., Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory [Cohen-Mansfield, 1997], Neuropsychiatric Inventory–Nursing Home (Wood et al., 2000), and depression (Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia [Alexopoulos et al., 1988]), a small number of studies used self-developed tools to measure staff knowledge and attitudes related to dementia staff training (Chang et al., 2006; Kemeny et al., 2006; Rosen et al., 2002). The heterogeneity of tools is observed across the training topics listed in Table 2.

Effectiveness of Training on Staff and Resident Outcomes

Twenty-eight of the 29 included studies reported staff outcomes (see Table 1). Twenty-five had favorable staff outcomes and three showed no statistical difference (Bökberg et al., 2019; Crogan & Evans, 2001; Huizing et al., 2006). Staff knowledge was the most frequently measured staff outcome that showed statistically significant improvement after the training intervention (n = 15), other studies reported statistically significant improvements in staff confidence and competence after the training intervention (n = 5), staff attitudes after training (n = 3), and staff communication skills after training (n = 3).

Thirteen studies reported on a wide range of resident outcomes (listed in Table 1) related to training and each of these studies reported at least one positive resident outcome. In seven studies, the authors found that resident behavior was positively affected after implementing a training intervention: reduced responsive behaviors (Arco & Du Toit, 2006), increased positive affect (Magai et al., 2002), improved QoL (p = .0042), decreased agitation (p = .0076) and decreased overall neuropsychiatric symptoms (p < .001) (Ballard et al., 2018), and decreased agitation which was maintained at the 3- and 6-month follow-up (p = .01) (Burgio et al., 2002). Additionally, two studies showed that residents had increased independence in self-care activities (p = .04) (Burgio et al., 2001) and improved “dressing” and “transferring” scores on the Katz ADL instrument (Leone et al., 2013) compared to the control groups, after staff participated in a communications training intervention, and apathy training, respectively. Lastly, there were significant reductions in resident reports of constant pain (p ≤ .001) and improvements in resident pain reassessments (p < .05) after staff were provided pain management training (Jones et al., 2004). In a separate study, decreased pain levels in residents were found (p = .006) after staff completed the depression training program (Smith et al., 2013).

Expert Panel Discussion

The literature review results were examined by the expert panel and the salient findings and gaps in knowledge identified by the panel were: (1) staff training was heterogeneous in almost all aspects including content, facilitation, duration, processes for monitoring effectiveness, and measurement tools; (2) the lack of any evidence of staff training in LMICs; (3) the absence of any international collaboration in training, and the local and regional scale of the training that was often limited to one home; (4) there was no macro-level measurement of staff training or indication of how staff training was documented that would allow aggregation of data between LTC homes; and (5) training appeared to be effective and positively influenced a broad range of resident and staff outcomes. Based on these findings, it was clear that there was no extant international measurement infrastructure and that the current literature was exclusive of LMICs; therefore, there was a need to create inclusive and accessible CDEs that could capture basic data internationally.

First, the expert panel acknowledged individual privileges and the discrepancies in resources and staffing as well as differences in system priorities between high, middle, and low-income countries. From this lens, the expert panel required that the proposed CDE candidates be feasible and applicable in a multitude of sociopolitical conditions in order to include data from LMICs. Further, we recognized that due to differences in languages, a CDE with nuanced or complex theoretical concepts may be lost in translation (e.g., self-efficacy as a primarily Western notion may not be easily translated or understood in other cultures) or may not be considered relevant. The proposed CDEs needed to be single-items that were simple, clear, and have face validity in a wide variety of social contexts in order to have buy-in from understaffed or under-resourced settings.

Second, the expert panel discussed how staff training could be reflected in a small number of meaningful CDEs. For example, it was important that training be current in order to keep staff up-to-date with relevant practices. There was further expert consensus that fewer items were preferred to a higher number of CDEs to increase the probability of implementation in high and low-income countries given the complex characteristics of LTC settings. Third, the expert panel discussed the critical need to evaluate the staff training using a validated measure as the literature review suggested that training has positive staff and resident impacts, but several studies reported their own unstandardized instruments. The expert panel considered the quality of the measurement tool and included the aspect of using standardized measurement tools to ensure that the same information can be gathered, compared and aggregated about staff and residents. To this end, the expert panel determined that CDEs focused on the presence and the measurement of staff training will begin to fill a current international data gap. Lastly, the expert panel discussed that the permissible values should be binary “yes” or “no” rather than Likert scales or scales that use terms with room for interpretation (e.g., “sometimes,” “often”). The CDEs needed to be accessible, feasible, clear, and not resource-intensive to answer in order to increase their likelihood of implementation into LTC settings.

From the WE-THRIVE expert panel discussions described above, the members focused on the necessity of basic data elements, that is, the presence and measurement of staff training related to staff and resident outcomes in LTC as an initial step to conduct cross-country comparative research. Therefore, three candidate CDEs were suggested to lay the groundwork for this critical knowledge building. The suggested CDEs are: (1) “was there institutional training provided to staff in the last 12 months?” with a binary choice of “yes” or “no,” followed by (2) “was there evaluation of a staff-related outcome using a standardized measure?,” and (3) “was there evaluation of resident-related outcome using a standardized measure?” both with a “yes” or “no”. This critical knowledge will support LTC workforce needs and continue to contribute to evidence related to staff training, which may inform the development of policies for a sustainable and equitable LTC system which are needed (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division, 2019; WHO, 2017). It is important to note that these are proposed CDEs are an initial starting point, and subject to change according to the emerging literature and future ongoing consultations with the broader academic and LTC community.

Discussion

This work presents the process of developing CDEs related to staff training in LTC homes; a literature review about staff training was completed, and the results were presented and discussed by an international expert panel as part of WE-THRIVE’s “Workforce and Staffing” subgroup. Best practices and a systematic method combining evidence in expert opinion were used to develop the candidate CDEs. The literature review results illuminated significant heterogeneity in staff training and use of measurement, a paucity of any international collaboration to evaluate staff training in LTC, as well as an absence of evidence about staff training from LMICs. The expert panel determined that a greater baseline understanding about whether training is provided and measured across different jurisdictions and countries is critical to understand inequities in professional development opportunities. A macro-level measurement infrastructure that can be applied to high- and low-income countries will begin to inform the development of LTC staff training benchmarks and quality standards aimed at ensuring research integrity, public accountability, and equitable allocation training.

Considerations from the expert panel about the quality of measurement tools used is consistent with previous staff training literature. Concerns with measurement have been longstanding in previous reviews of staff training programs in LTC (Aylward et al., 2003; Beeber et al., 2010; Kuske et al., 2007), and there is a consensus for a greater need for more rigorous evaluation of training with validated and standardized tools. Proposed CDEs that are explicit about the use of standardized tools may motivate more robust measurement and emulate the aspirational values of WE-THRIVE to build capacity and support cross-country research.

Significance and Next Steps

The WE-THRIVE initiative seeks to facilitate international research in order to support high quality of care for older adults and comparative research in LTC, such that findings between different researchers in diverse countries can be seamlessly pooled to create appropriate policies and interventions for LTC staff training (Corazzini et al., 2019). The findings of the current review can aid in the creation and development of appropriate LTC strategies and documentation related to staff training (Lepore & Corazzini, 2019). Accurately capturing such foundational data can benefit policymakers to create guidelines and benchmarks about staff training, and also help inform LTC home administrators about resource allocation. For example, if the proposed CDE data about staff training was collected and shared between regions, it could promote a greater understanding about the degree of capacity building and effects of staff training for staff and residents.

The iterative process and stakeholder engagement are critical elements to the successful development and use of CDEs according to Redeker et al. (2015). The input of stakeholders in the development and use of CDEs promotes harmonization nationally and internationally (Choquet et al., 2015; Redeker et al., 2015). We plan on engaging in dialogue and discussions with the researchers and LTC stakeholders to get feedback about the proposed CDEs and the feasibility of these CDEs. Future directions include efforts to advance the development of CDEs through continued international research as part of WE-THRIVE. Further investigations are required to examine if the proposed CDEs are able to be translated across cultural, geographical and institutional barriers, as well as how the proposed CDEs will improve data quality and opportunities for comparison between international researchers.

Strengths and Weaknesses

One strength of this review is in the robust approach of expert consultation based on the diverse group of researchers from the WE-THRIVE initiative. Another strength is that we used a systematic approach when conducting the literature review that included a search generated by an information specialist spanning the last 20 years, and independent reviewers who completed the full-text screen and extractions. The search was limited to English only titles which may have excluded training programs from non-English speaking parts of the world. Additionally, publication bias could be a limitation as training that was not found to positively influence outcomes may not have been published. Lastly, although there are dozens of countries represented in the WE-THRIVE group, not all countries are presented in the panel, specifically countries in the Global South and Africa. The expert panel was composed of experts from high-income English-speaking countries. Moving forward, WE-THRIVE has active online campaigns to strongly encourage researchers in LTC from LMIC and non-English speaking countries to participate with the WE-THRIVE initiative and the workforce domain to ensure the selected LTC CDEs are relevant and applicable to these contexts.

Conclusion

In summary, this paper presented a systematic process by which an international expert panel proposed three CDEs as part of the WE-THRIVE CDE initiative to advance international research related to staff training in LTC. Proposing appropriate CDEs can bolster comparative research and create the evidence-base for policy and LTC decision-making. The three candidate CDEs proposed are accessible, feasible, and intended to be ecologically viable in LMICs in order to fill current knowledge gaps to evaluate staff training. Researchers must continue to be mindful that observed differences in training across countries are likely influenced by social policies and context specific to each jurisdiction, thus continuous assessments are required. These proposed CDEs are positioned as the starting point for staff training, and are subject to change based on new evidence, feedback from LTC stakeholders, and the cultural, political, and institutional changes that may occur.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the guidance and support of Drs Kirsten Corazzini and Michael Lepore, co-chairs of the WE-THRIVE consortium.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Charlene H. Chu  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0333-7210

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0333-7210

Katherine S. McGilton  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2470-9738

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2470-9738

Kim N. Le  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3517-9878

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3517-9878

Veronique Boscart  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7420-1978

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7420-1978

Franziska Zúñiga  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8844-4903

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8844-4903

References

- Alexopoulos G. S., Abrams R. C., Young R. C., Shamoian C. A. (1988). Cornell scale for depression in dementia. Biological Psychiatry, 23(3), 271–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimers Disease International. (2013). World Alzheimer report 2013 journey of caring: Analysis of long-term care for Dementia. Author. http://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2013.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Arco L., Du Toit E. (2006). Effects of adding on-the-job feedback to conventional analog staff training in a nursing home. Behavior Modification, 30(5), 713–735. 10.1177/0145445505281058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Aylward S., Stolee P., Keat N., Johncox V. (2003). Effectiveness of continuing education in long-term care: A literature review. The Gerontologist, 43(2), 259–271. 10.1093/geront/43.2.259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard C., Corbett A., Orrell M., Williams G., Moniz-Cook E., Romeo R., Woods B., Garrod L., Testad I., Woodward-Carlton B., Woodward-Carlton B. (2018). Impact of person-centred care training and person-centred activities on quality of life, agitation, and antipsychotic use in people with dementia living in nursing homes: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. PLoS Medicine, 15(2), e1002500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard J. R., Officer A., de Carvalho I. A., Sadana R., Pot A. M., Michel J.-P., Lloyd-Sherlock P., Epping-Jordan J. E., Peeters G. G., Mahanani W. R., Chatterji S. (2016). The World report on ageing and health: A policy framework for healthy ageing. Lancet (London, England), 387(10033), 2145–2154. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00516-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeber A. S., Zimmerman S., Fletcher S., Mitchell C. M., Gould E. (2010). Challenges and strategies for implementing and evaluating dementia care staff training in long-term care settings. Alzheimer’s Care Today, 11(1), 17–39. 10.1097/ACQ.0b013e3181cd1a52 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bökberg C., Behm L., Wallerstedt B., Ahlström G. (2019). Evaluation of person-centeredness in nursing homes after a palliative care intervention: Pre-and post-test experimental design. BMC Palliative Care, 18(1), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker D. J., Sure C. (2006). Dementia Care Mapping (DCM): Initial validation of DCM in UK field trails. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21, 1018–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgio L. D., Allen-Burge R., Roth D. L., Bourgeois M. S., Dijkstra K., Gerstle J., Bankester L. (2001). Come talk with me: Improving communication between nursing assistants and nursing home residents during care routines. The Gerontologist, 41(4), 449–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgio L. D., Stevens A., Burgio K. L., Roth D. L., Paul P., Gerstle J. (2002). Teaching and maintaining behavior management skills in the nursing home. The Gerontologist, 42(4), 487–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspar S., Cooke H. A., Phinney A., Ratner P. A. (2016, September 1). Practice change interventions in long-term care facilities: What works, and why? Canadian Journal on Aging, 35(3), 372–384. 10.1017/S0714980816000374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. C., Wykle M. L., Madigan E. A. (2006). The effect of a feeding skills training program for nursing assistants who feed dementia patients in Taiwanese nursing homes. Geriatric Nursing, 27(4), 229–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choquet R., Maaroufi M., De Carrara A., Messiaen C., Luigi E., Landais P. (2015). A methodology for a minimum data set for rare diseases to support national centers of excellence for healthcare and research. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 22(1), 76–85. 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J. (1997). Conceptualization of agitation: Results based on the Cohen-Mansfield agitation inventory and the agitation behavior mapping instrument. International Psychogeriatrics, 8(s3), 309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper E., Spilsbury K., McCaughan D., Thompson C., Butterworth T., Hanratty B. (2016). Priorities for the professional development of registered nurses in nursing homes: A Delphi study. Age and Ageing, 46(1), 39–45. 10.1093/ageing/afw160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corazzini K. N., Anderson R. A., Bowers B. J., Chu C. H., Edvardsson D., Fagertun A., Gordon A. L., Leung A. Y., McGilton K. S., Meyer J. E., Lepore M. J., & WE-THRIVE. (2019). Toward common data elements for international research in long-term care homes: Advancing person-centered care. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 20(5), 598–603. 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.01.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crogan N. L., Evans B. C. (2001). Nutrition education for nursing assistants: An important strategy to improve long-term care. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 32(5), 216–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dassel K., Butler J., Telonidis J., Edelman L. (2020). Development and evaluation of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (ADRD) best care practices in long-term care online training program. Educational Gerontology, 46(3), 150–157. [Google Scholar]

- Davis E., Lundstrom K. (2011, July). Creating effective staff development committees: A case study. New Library World, 112(7/8), 334–346. 10.1108/03074801111150468 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa R., Colombo F. (2009). The long-term care workforce: Overview and strategies to adapt supply to a growing demand, OECD health working papers. OECD. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/the-long-term-care-workforce-overview-and-strategies-to-adapt-supply-to-a-growing-demand_225350638472 [Google Scholar]

- Ghandehari O. O., Hadjistavropoulos T., Williams J., Thorpe L., Alfano D. P., Dal Bello-Haas V., Malloy D. C., Martin R. R., Rahaman O., Zwakhalen S. M. G., Carleton R. N., Hunter P. V., Lix L. M. (2013). A controlled investigation of continuing pain education for long-term care staff. Pain Research and Management, 18(1), 11–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene C., Canning D., Wilson J., Bak A., Tingle A., Tsiami A., Loveday H. (2018). I-Hydrate training intervention for staff working in a care home setting: An observational study. Nurse Education Today, 68, 61–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T-T., Wu S-C. (2008). Evaluation of a training programme on knowledge and compliance of nurse assistants’ hand hygiene in nursing homes. The Journal of Hospital Infection, 68(2), 164–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizing A. R., Hamers J. P. H., Gulpers M. J. M., Berger M. P. F. (2006). Short-term effects of an educational intervention on physical restraint use: A cluster randomized trial. BMC Geriatrics, 6, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein S., Manthorpe J. (2005). An international review of the long-term care workforce: Policies and shortages. Journal of Aging and Social Policy, 17(4), 75–94. 10.1300/J031v17n04_05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens B., De Visschere L., van der Putten G. J., de Lugt–Lustig K., Schols J. M., Vanobbergen J. (2016). Effect of an oral healthcare protocol in nursing homes on care staffs’ knowledge and attitude towards oral health care: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Gerodontology, 33(2), 275–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K. R., Fink R., Vojir C., Pepper G., Hutt E., Clark L., Scott J., Martinez R., Vincent D., Mellis B. K. (2004). Translation research in long-term care: Improving pain management in nursing homes. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 1, S13–S20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane R. A. (2003). Human resources for long-term care: Lessons from the United States. World Health Organization Collection on Long-Term Care. https://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/policy_issues_ltc.pdf#page=205

- Kemeny B., Boettcher I. F., DeShon R. P., Stevens A. B. (2006). Using experiential techniques for staff development: Liking, learning, and doing. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 32(8), 9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuske B., Hanns S., Luck T., Angermeyer M. C., Behrens J., Riedel-Heller S. G. (2007, October). Nursing home staff training in dementia care: A systematic review of evaluated programs. International Psychogeriatrics, 17(5), 818–841. 10.1017/S1041610206004352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone E., Deudon A., Bauchet M., Laye M., Bordone N., Lee J., Piano J., Friedman L., David R., Delva F., Delva F. (2013). Management of apathy in nursing homes using a teaching program for care staff: The STIM-EHPAD study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(4), 383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepore M., Corazzini K. (2019). Advancing international research on long-term care: Using adaptive leadership to build consensus on international measurement priorities and common data elements. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, 5, 233372141986472. 10.1177/2333721419864727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie C. S., Peragine G. (2003). Measuring and enhancing self-efficacy among professional caregivers of individuals with dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias®, 18(5), 291–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]