Abstract

Objective

To evaluate a rare case of a postmenopausal woman with hirsutism and virilization due to Leydig cell tumors (LCTs) of both ovaries.

Methods

In this challenging case, the diagnostic studies included the detection of total/free testosterone, hemoglobin, and estradiol levels; adrenal computed tomography; and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging.

Results

A 61-year-old woman presented for the evaluation of hirsutism. Physical examination revealed normal vital signs and evidence of virilization. The baseline laboratory findings were hemoglobin level of 16.2 g/dL (reference, 12.0-15.5 g/dL), total testosterone level of 803 ng/dL (reference, 3-41 ng/dL), and free testosterone level of 20.2 pg/mL (reference, 0.0-4.2 pg/mL). Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging showed bilateral homogeneous ovarian enhancement. Based on the magnetic resonance imaging findings and clinical presentation, the patient was diagnosed with ovarian hyperthecosis and underwent laparoscopic bilateral oophorectomy. Pathology confirmed LCTs in both ovaries. Six months later, testosterone levels normalized, with significant improvement in hirsutism and virilization.

Conclusion

Clinicians should be aware of androgen-secreting tumors, including rare bilateral LCTs in postmenopausal women presenting with progressing hirsutism and virilization. Marked hyperandrogenemia with total testosterone level of >150 ng/dL (5.2 nmol/L) or serum dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate level of >700 μg/dL (21.7 mmol/L) is typically found. It should be recognized that diffuse stromal Leydig cell hyperplasia and small LCTs may be missed on imaging, and in some cases only pathology can confirm the result.

Key words: hirsutism, Leydig cell tumor, virilization

Abbreviations: FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LCT, Leydig cell tumor; LH, luteinizing hormone; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

Ovarian Leydig cell tumors (LCTs), a subtype of ovarian steroid cell tumor, accounts for <0.1% of all ovarian tumors.1 LCTs may occur in a wide range of ages, have relatively low rates of malignancy, and have an excellent prognosis, following surgical removal. The clinical manifestations of these tumors are associated with excessive secretion of androgenic hormones and tumor mass effects. These tumors generally occur in postmenopausal woman with virilizing symptoms and are almost always unilateral.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Only a limited number of patients with bilateral ovarian LCTs have been previously described. We hereby report a 61-year-old woman who presented with hirsutism and virilization and bilateral ovarian LCTs. In this challenging case, the diagnostic studies included the detection of total and free testosterone, hemoglobin, and estradiol levels; adrenal computed tomography; and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Case Report

A 61-year-old woman presented for the evaluation of increased facial hair growth, frontal balding, deepening of voice, acne, oily skin, increased muscle mass, and increased libido. Her medical history was significant for type 1 diabetes mellitus, treated papillary thyroid cancer, and breast cancer. Physical examination revealed normal vital signs and positive signs of virilization, including coarse hair along the upper lip, chin, and inner thigh (Ferriman-Galloway score 9; normal, <8), acne, and clitoromegaly. The patient also had bilateral breast atrophy and increased skeletal muscle mass. The baseline laboratory values were hemoglobin level of 16.2 g/dL (reference, 12.0-16.9 g/dL), total serum testosterone level of 803 ng/dL (reference, 3-14 ng/dL), free testosterone level of 20.2 ng/dL (reference, 0.0-4.2 ng/dL), estradiol level of 77 pg/mL (reference, 6.0-54.7 pg/mL), estrone level of 148 pg/mL (reference, 7-40 pg/mL), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level of 11.5 mIU/mL (reference, 25.8-134.8 mIU/mL), luteinizing hormone (LH) level of 6.90 mIU/mL (reference, 7.7-58.5 mIU/mL) (Table), androstenedione level of 28 ng/dL (reference, 31-701 ng/dL), dehydroepiandrosterone level of 512 ng/dL (reference, 31-701 ng/dL), dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate level of 99.9 μg/dL (reference, 19-220 μg/dL), inhibin A level of 2.3 pg/mL (reference, <5 pg/mL), inhibin B level of 76 pg/mL (reference, <51 pg/mL), 17-α-hydroxyprogesterone level of 187 ng/dL (reference, < 51 ng/dL), 11-deoxycortisol level of 0.06 ng/dL (reference, 0-37 ng/dL), and adrenocorticotropic hormone level of 7.7 pg/mL (reference, 7.2-63.3 pg/mL). A dexamethasone-suppression test was normal (serum cortisol level <0.8 μg/dL). Computerized axial scan of adrenal glands and abdominal ultrasound were normal. Transvaginal ultrasound did not show any ovarian pathology and also did not reveal any endometrial hyperplasia (endometrial thickness, 0.2 cm). An MRI of the pelvis showed homogenous ovarian enhancement bilaterally consistent with ovarian hyperthecosis (Fig. 1). With this diagnosis, the patient underwent laparoscopic bilateral oophorectomy, and histopathologic examination of the resected ovaries showed neoplasms in both ovaries. The lesions included cells with round nuclei, abundant granular cytoplasm, and lipofuscin stained brightly with inhibin scattered throughout (Fig. 2), consistent with hilar type LCT. Six weeks later, her serum testosterone, serum estradiol, estrone, LH, and FSH levels normalized to the normal range for women (Table). Six months following surgery, the patient had significant improvement in hirsutism and virilization symptoms.

Table.

Relevant Laboratory Examination Valuesa

| Test | Preoperative | Postoperative | Reference value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total testosterone | 803 | 5.1 | 3-41 ng/dL |

| Free testosterone | 20.2 | 0.2 | 0.0-4.2 pq/mL |

| Estradiol | 77 | 22 | 6.0-54.7 pq/mL |

| Estrone | 148 | 18 | <65 pg/mL |

| Luteinizing hormone | 6.90 | 42 | 13.1-86.5 mIU/mL |

| Follicle-stimulating hormone | 11.5 | 68 | 25.8-134.8 mIU/mL |

The laboratory examination values were obtained prior to bilateral oophorectomy. The postoperative values were obtained 6 weeks following surgery.

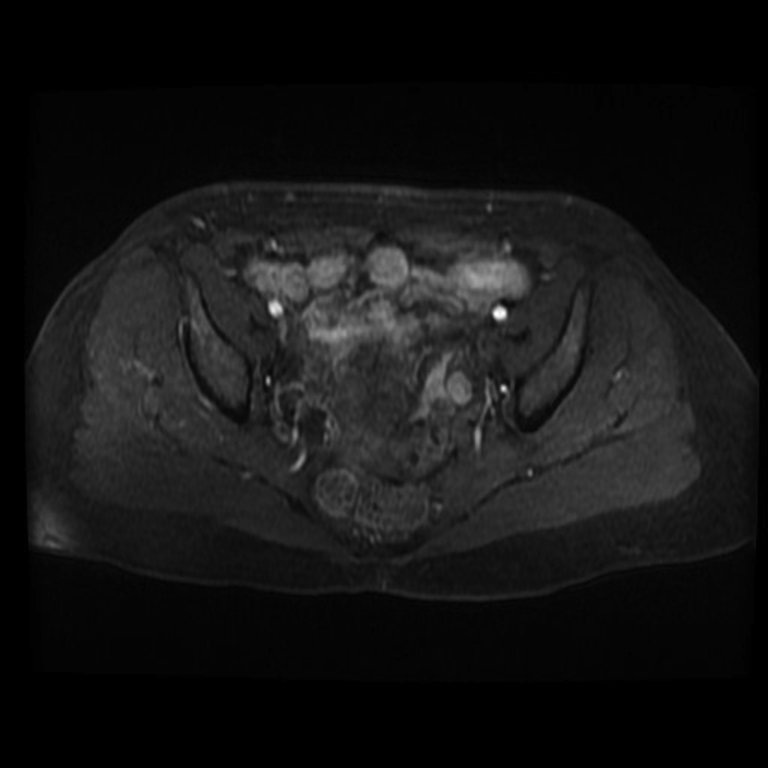

Fig. 1.

Pelvic MRI showing homogenous ovarian enhancement bilaterally consistent with ovarian hyperthecosis. MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

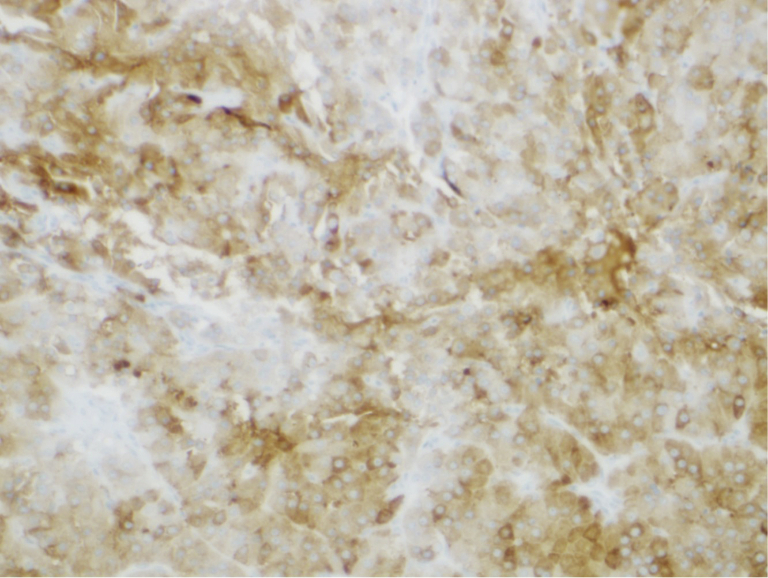

Fig. 2.

Histology showing cells with round nuclei, abundant granular cytoplasm, and lipofuscin stained brightly with inhibin scattered throughout consistent with hilar type LCT. LCT = Leydig cell tumor.

Discussion

Mild hyperandrogenism and hirsutism in young women are most commonly related to polycystic ovary syndrome.7 However, hyperandrogenism, especially with virilization, occurring in a postmenopausal woman usually indicates excessive testosterone secretion from an adrenal or ovarian source.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Our patient had no clinical features of Cushing syndrome, with a normal serum adrenocorticotropic hormone level, normal response to 1-mg overnight dexamethasone suppression, normal dehydroepiandrosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate levels, and normal-size adrenal glands on MRI. Thus, in our patient presenting with hirsutism and virilization, an ovarian source was the most likely cause of testosterone overproduction. Our patient had hirsutism and virilization, including frontal balding, deepening of voice, increased muscle mass, breast atrophy, altered body fat distribution, and clitoromegaly along with elevated serum testosterone levels in the normal range for men. These features in a postmenopausal woman clearly support the diagnosis of an ovarian tumor, hilar cell hyperplasia, or ovarian hyperthecosis.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Ovarian tumors associated with severe hyperandrogenic features are primitive tumors of the sexual cords and stroma (including granulosa cell tumors, Sertoli Leydig tumors, and thecoma) and steroid cell tumors (including luteomas and LCTs). Others include primary and secondary tumors containing functioning struma.9

Detailed imaging procedures performed in our patient included ultrasound of the abdomen and pelvis, transvaginal ultrasonography, computerized axial scan of the abdomen and pelvis, and MRI of the abdomen and pelvis. Of these imaging studies, only MRI indicated bilaterally enlarged ovaries, consistent with a diagnosis of ovarian hyperthecosis. Usually, patients with ovarian hyperthecosis present with severe hyperandrogenic features because of excessive testosterone secretion by luteinized thecal cells. Additional available imaging procedures include ovarian vein sampling for testosterone and positron emission tomography.10,11 We did not perform these imaging procedures in our patient, although a positron emission tomography scan may have been useful. Thus, with a preoperative diagnosis of ovarian hyperthecosis, the patient underwent laparoscopic bilateral oophorectomy. However, histologic examination of the resected ovaries confirmed bilateral LCTs. LCTs are rare ovarian steroid neoplasms and classified as hilar or nonhilar. Although Leydig cells can be nonsecreting, approximately 75% of patients have an increased production of testosterone, as seen in our patient. Rarely, patients in postmenopausal state may present with features of hyperestrogenism, including the resumption of menstrual periods, and rarely, endometrial carcinoma.12 Interestingly, younger women may present with amenorrhea and virilization.13 There was no history of menstrual bleeding in our patient and ultrasound imaging did not reveal the thickening of the endometrium. This may be related to early diagnosis or low tumor volume and relatively low serum levels of estradiol.14 It is also interesting to note that the relatively low serum levels of LH and FSH may have been related to the high levels of estradiol. Following the resection of the LCTs, the LH and FSH levels returned to the postmenopausal range. Our patient also had secondary erythrocytosis resulting from excessive androgens that returned to normal following the surgical resection of the LCTs. Kozan et al14 reported a 55-year-old woman with an LCT and extreme hyperandrogenism, erythrocytosis, recurrent pulmonary embolism, and sleep apnea. Following the surgical removal of the tumor, her virilization, erythrocytosis, and sleep apnea completely resolved. Although the surgical removal of LCTs is the preferred treatment, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs given prior to surgery can serve to rule out functional hyperandrogenism like stromal hyperplasia or ovarian hyperthecosis, which are more common in postmenopausal women than LCTs. In fact, Klotz et al15 administered a gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog to a woman that brought about a decrease in serum testosterone level, although she subsequently underwent surgery.

LCTs are almost always unilateral with virilization symptoms and are classically seen in perimenopausal or postmenopausal women. Bilateral LCTs are rare, with only 7 reported cases in the literature.16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 The first case of bilateral LCTs was described in 1949, and following this, 6 more cases were reported.16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 Our patient represents the eighth case in these case series. These postmenopausal patients presented with hirsutism and virilization symptoms, and interestingly, 1 patient had excess redness of the face, apparently related to polycythemia. In the reported cases of bilateral LCTs, radiological studies were not useful to localize the tumors. However dynamic contrast-enhanced and diffusion-weighted MRI, positron emission tomography scans, and bilateral ovarian vein sampling studies may be useful. Generally, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is the preferred surgical approach in these patients with bilateral LCTs.

Conclusion

In conclusion, LCTs of the ovary, although unilateral in the majority of cases, bilateral tumors can occur.16, 17, 18, 19 Our patient is the eigth case in the published literature. Diffuse stromal Leydig cell hyperplasia and small LCTs may be missed in routine imaging, and only histologic examination can confirm the diagnosis.

Disclosure

The authors have no multiplicity of interest to disclose. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of Army/Navy/Air Force, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

References

- 1.Roux-Guinot S., Gorin I., Vadrot D., Djid R., Bethoux J.P., Escande J.P. Androgenic alopecia revealing an androgen secreting ovarian tumor. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2001;128(11):1241–1244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baiocchi G., Manci N., Angeletti G., Celleno R., Fratini D., Gilardi G. Pure Leydig cell tumour (hilus cell) of the ovary: a rare cause of virilization after menopause. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1997;44(2):141–144. doi: 10.1159/000291506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yetkin D.O., Demirsoy E.T., Kadioglu P. Pure leydig cell tumour of the ovary in a post-menopausal patient with severe hyperandrogenism and erythrocytosis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2011;27(4):237–240. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2010.490611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takeuchi S., Ishihara N., Ohbayashi C., Itoh H., Maruo T. Stromal Leydig cell tumor of the ovary. Case report and literature review. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1999;18(2):178–182. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199904000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sherf S., Martinez D. Leydig cell tumor in the post-menopausal woman: case report and literature review. Acta BioMed. 2016;87(3):310–313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Souto S.B., Baptista P.V., Braga D.C., Carvalho D. Ovarian Leydig cell tumor in a post-menopausal patient with severe hyperandrogenism. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2014;58(1):68–75. doi: 10.1590/0004-2730000002461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azziz R., Sanchez L.A., Knochenhauer E.S. Androgen excess in women: experience with over 1000 consecutive patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(2):453–462. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rittmaster R.S. Hirsutism. Lancet. 1997;349(9046):191–195. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07252-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen V.W., Ruiz B., Killeen J.L., Coté T.R., Wu X.C., Correa C.N. Pathology and classification of ovarian tumors. Cancer. 2003;97(suppl 10):2631–2642. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozgun M.T., Batukan C., Turkyilmaz C., Dolanbay M., Mavili E. Selective ovarian vein sampling can be crucial to localize a Leydig cell tumor: an unusual case in a postmenopausal woman. Maturitas. 2008;61(3):278–280. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kong J., Park Y.M., Choi Y.S., Cho S., Lee B.S., Park J.H. Diagnosis of an indistinct Leydig cell tumor by positron emission tomography-computed tomography. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2019;62(3):194–198. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2019.62.3.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang T.Y., Holaday W.J. An ovarian hilus-cell tumor associated with endometrial carcinoma: report of a case. Am J Clin Pathol. 1970;54(1):147–150. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/54.1.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faria A.M., Perez R.V., Marcondes J.A. A premenopausal woman with virilization secondary to an ovarian Leydig cell tumor. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7(4):240–245. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kozan P., Chalasani S., Handelsman D.J., Pike A.H., Crawford B.A. A Leydig cell tumor of the ovary resulting in extreme hyperandrogenism, erythrocytosis, and recurrent pulmonary embolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(1):12–17. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klotz R.K., Müller-Holzner E., Fessler S. Leydig-cell-tumor of the ovary that responded to GnRH-analogue administration – case report and review of the literature. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2010;118(5):291–297. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1225351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andola U.S., Waddenkeri S., Patil P., Andola S.K. Bilateral Leydig cell tumor of ovary: a rare case report. Indian J Obstetrics Gyn. 2019;103(2):334–336. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanz O.A., Martinez P.R., Guarch R.T., Goñi M.J., Alcazar J.L. Bilateral Leydig cell tumour of the ovary: a rare cause of virilization in postmenopausal patient. Maturitas. 2007;57(2):214–216. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luton J.P., Clerc J., Paoli V., Bonnin A., Dumez Y., Vacher-Lavenu M.C. Bilateral Leydig cell tumor of the ovary in a woman with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. The first reported case. Presse Med. 1991;20(3):109–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duun S. Bilateral virilizing hilus (Leydig) cell tumors of the ovary. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1994;73(1):76–77. doi: 10.3109/00016349409013401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sternberg W.H. The morphology, androgenic function, hyperplasia, and tumors of the human ovarian hilus cells. Am J Pathol. 1949;25(3):493–521. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baramki T.A., Leddy A.L., Woodruff J.D. Bilateral hilus cell tumors of the ovary. Obstet Gynecol. 1983;62(1):128–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langley F.A. Sertoli and Leydig cell in relation to ovarian tumors. J Clin Pathol. 1954;7(1):10–17. doi: 10.1136/jcp.7.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]