To the Editor:

As the developers of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Hospital Mortality and Readmission measures, we read with interest the recent paper by Neira and colleagues (1). The authors document a substantial increase in 30-day mortality for patients hospitalized for COPD between the years 2006–2010, 2010–2014, and 2014–2017, corresponding with the period before, in the run-up to, and after the implementation of Medicare’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. Over this same period, 30-day readmission rates were observed to decline, raising concerns that hospital efforts intended to prevent readmissions might have inadvertently led to harm. As part of their analysis, the authors estimate that some 1,196 deaths might be attributable to this federal program.

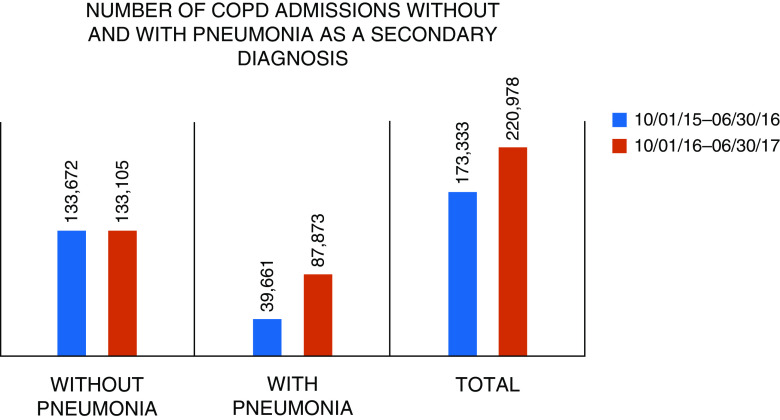

Although unintended consequences of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program are one potential explanation for the apparent increase in 30-day mortality, our own analysis of Medicare claims data for this same period suggests that the increase was an artifact of recent changes in hospital documentation and coding practices. In 2016, hospitals received updated coding instructions for cases in which a patient is admitted for a COPD exacerbation complicated by pneumonia. In such instances, hospitals were guided to use COPD—rather than pneumonia—as the principal diagnosis (2). Within the span of 1 year, we observed a large increase (both in absolute and relative terms) in patients entering the COPD Measure Cohort who carried a secondary diagnosis of pneumonia. Between 2015–2016 and 2016–2017, the COPD cohort grew by approximately 47,000 cases, a figure almost entirely accounted for by an additional 48,000 cases with pneumonia who previously would have been counted in the pneumonia measure (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Changes in the number of hospitalizations for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with and without pneumonia in 2015–2016 versus 2016–2017. COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

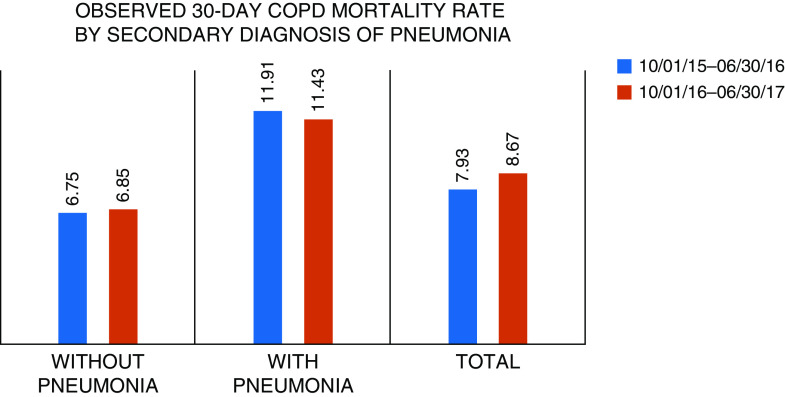

This alteration in the composition of the COPD cohort is critical to interpreting changes in COPD mortality. Patients hospitalized for COPD who carry a secondary diagnosis of pneumonia have a 30-day mortality rate nearly twice as high as patients who do not (Figure 2). To further illuminate this issue, we stratified the COPD Measure Cohort according to the presence or absence of pneumonia and compared mortality rates in the 2015–2016 and 2016–2017 time periods. We observed that the mortality rate was stable among patients with COPD without pneumonia and appeared to actually decrease modestly among those with pneumonia (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Observed 30-day mortality among cases hospitalized for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with and without pneumonia in 2015–2016 versus 2016–2017. COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Temporal changes and variations between hospitals in documentation and coding are well-established sources of bias in efforts to track mortality rates over time and to compare outcomes across hospitals (3, 4). We believe that the apparent increase in mortality demonstrated by Niera and colleagues is yet another example of the challenges inherent in measuring clinical outcomes using claims data.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors are supported by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop and maintain outcome measures for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pneumonia.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202009-3697LE on November 9, 2020

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Puebla Neira DA, Hsu ES, Kuo YF, Ottenbacher KJ, Sharma G. Readmissions reduction program, mortality and readmissions for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203:437–446. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202002-0310OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coding Clinic. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Association; 2016. Third Quarter: 15-16. Acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with pneumonia. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindenauer PK, Lagu T, Shieh M-S, Pekow PS, Rothberg MB. Association of diagnostic coding with trends in hospitalizations and mortality of patients with pneumonia, 2003-2009. JAMA. 2012;307:1405–1413. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, Priya A, Lindenauer PK. Variation in diagnostic coding of patients with pneumonia and its association with hospital risk-standardized mortality rates: a cross-sectional analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:380–388. doi: 10.7326/M13-1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.