Abstract

Problem

The surge in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases overwhelmed the health system in the Republic of Korea.

Approach

To help health-care workers prioritize treatment for patients with more severe disease and to decrease the burden on health systems caused by COVID-19, the government established a system to classify disease severity. Health-care staff in city- and provincial-level patient management teams classified the patients into the different categories according to the patients’ pulse, systolic blood pressure, respiratory rate, body temperature and level of consciousness. Patients categorized as having moderate, severe and very severe disease were promptly assigned to beds or negative-pressure isolation rooms for hospital treatment, while patients with mild symptoms were monitored in 16 designated facilities across the country.

Local setting

The case fatality rate was higher in the city of Daegu and the Gyeongsangbuk-do province (1.6%; 124/7756) than the rest of the country (0.5%; 7/1485).

Relevant changes

From 25 February to 26 March 2020, the ratio of negative-pressure isolation rooms per COVID-19 patient was below 0.15 in the city of Daegu and the Gyeongsangbuk-do province. In the rest of the country, this ratio decreased from 5.56 to 0.63 during the same period. Before the classification system was in place, eight (15.7%) out of the 51 deaths occurred at home or during transfer from home to health-care institutions.

Lessons learnt

Categorizing patients according to their disease severity should be a prioritized measure to ease the burden on health systems and reduce the case fatality rate.

Résumé

Problème

La flambée de cas de maladie à coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) a submergé le système de santé en République de Corée.

Approche

Afin d'aider le personnel soignant à mieux organiser la prise en charge des patients présentant une forme sévère de la maladie et d'alléger le fardeau que la COVID-19 fait peser sur le secteur des soins de santé, le gouvernement a établi un système de classification du degré de gravité. Des professionnels de la santé appartenant aux équipes de gestion des patients à l'échelle municipale et provinciale ont divisé les patients en différentes catégories selon leur rythme cardiaque, leur tension artérielle systolique, leur fréquence respiratoire, leur température corporelle et leur état de conscience. Les patients considérés comme souffrant d'une forme modérée, grave et extrêmement grave de la maladie ont rapidement été placés dans des lits ou des chambres d'isolement à pression négative pour recevoir un traitement hospitalier, tandis que les patients présentant de légers symptômes étaient surveillés dans 16 centres prévus à cet effet, disséminés dans le pays.

Environnement local

Le taux de létalité s'est révélé plus élevé dans la ville de Daegu et la province de Gyeongsang du Nord (1,6%; 124/7756) que dans le reste du pays (0,5%; 7/1485).

Changements significatifs

Entre le 25 février et le 26 mars 2020, la proportion de chambres d'isolement à pression négative par patient COVID-19 était inférieure à 0,15 dans la ville de Daegu et la province de Gyeongsang du Nord. Dans le reste du pays, cette proportion a diminué de 5,56 à 0,63 durant la même période. Avant l'instauration du système de classification, huit (15,7%) des 51 décès sont survenus à domicile ou lors du transfert vers les établissements de soins de santé.

Leçons tirées

Il faut privilégier la répartition des patients selon le degré de gravité de la maladie pour décharger le système de santé et réduire le taux de létalité.

Resumen

Situación

El aumento de los casos de la enfermedad por coronavirus de 2019 (COVID-19) saturó el sistema sanitario de la República de Corea.

Enfoque

Para ayudar a los profesionales sanitarios a dar prioridad al tratamiento de los pacientes con enfermedades más graves y para disminuir la carga que supone para los sistemas sanitarios debido a la COVID-19, el gobierno estableció un sistema de clasificación del grado de gravedad de las enfermedades. El personal sanitario de los equipos de gestión de los pacientes a nivel de ciudad y de provincia clasificó a los pacientes en las diferentes categorías según el pulso, la tensión arterial sistólica, la frecuencia respiratoria, la temperatura corporal y el nivel de conciencia de los pacientes. Los pacientes clasificados como con enfermedad moderada, grave y muy grave fueron asignados de inmediato a camas o salas de aislamiento con presión negativa para su tratamiento hospitalario, mientras que los pacientes con síntomas leves fueron supervisados en 16 instalaciones designadas en todo el país.

Marco regional

La tasa de letalidad fue mayor en la ciudad de Daegu y en la provincia de Gyeongsangbuk-do (1,6 %; 124/7756) que en el resto del país (0,5 %; 7/1485).

Cambios importantes

Del 25 de febrero al 26 de marzo de 2020, el cociente de las salas de aislamiento con presión negativa por cada paciente con la COVID-19 fue inferior a 0,15 en la ciudad de Daegu y en la provincia de Gyeongsangbuk-do. En el resto del país, este cociente disminuyó de 5,56 a 0,63 durante el mismo periodo. Antes de que se estableciera el sistema de clasificación, ocho (15,7 %) de las 51 muertes ocurrieron en el hogar o durante el traslado del hogar a las instituciones sanitarias.

Lecciones aprendidas

La clasificación de los pacientes según la gravedad de su enfermedad debería ser una medida prioritaria para aliviar la carga del sistema sanitario y reducir la tasa de letalidad.

ملخص

المشكلة سيطر الارتفاع في حالات الإصابة بمرض فيروس كورونا (كوفيد 19) على النظام الصحي في جمهورية كوريا.

الأسلوب في سبيل مساعدة العاملين في مجال الرعاية الصحية في منح أولوية العلاج للمرضى الذين يعانون من شدة أكثر للمرض، ولتقليل العبء على النظم الصحية الناجم عن كوفيد 19، قامت الحكومة بإنشاء نظام لتصنيف شدة المرض. قام موظفو الرعاية الصحية، في فرق إدارة المرضى على مستوى المدينة والمقاطعة، بتصنيف المرضى إلى فئات مختلفة وفقًا لنبض المرضى، وضغط الدم الانقباضي، ومعدل التنفس، ودرجة حرارة الجسم، ومستوى الوعي. المرضى الذين تم تصنيفهم على أنهم يعانون من أعراض معتدلة، وشديدة، وشديدة للغاية، تم على وجه السرعة منحهم أسرّة، أو غرف عزل الضغط السلبي للعلاج في المستشفى، بينما خضع المرضى الذين يعانون من أعراض خفيفة للمراقبة في 16 منشأة مخصصة في جميع أنحاء البلاد.

المواقع المحلية كان معدل الوفيات الحالات أعلى في مدينة دايجو، ومقاطعة جيونج سانج بوك دو (1.6%؛ 124/7756)، مقارنة ببقية البلاد (0.5%؛ 7/1485).

التغيّرات ذات الصلة في الفترة من 25 فبراير/شباط إلى 26 مارس/آذار 2020، كانت نسبة غرف عزل الضغط السلبي لكل مريض مصاب بكوفيد 19 أقل من 0.15 في مدينة دايجو ومقاطعة جيونج سانج بوك دو. وفي باقي أنحاء البلاد، انخفضت هذه النسبة من 5.56 إلى 0.63 خلال نفس الفترة. قبل وضع نظام التصنيف قيد التنفيذ، حدثت ثماني حالات وفاة (15.7%) من أصل 51 حالة وفاة في المنزل، أو أثناء النقل من المنزل إلى مؤسسات الرعاية الصحية.

الدروس المستفادة إن تصنيف المرضى وفقًا لشدة مرضهم يجب أن يكون إجراءً له الأولوية لتخفيف العبء على النظام الصحي وتقليل معدل وفيات الحالات.

摘要

问题

2019 冠状病毒病(新型冠状病毒肺炎)病例激增导致韩国卫生系统不堪重负。

方法

为帮助医护人员优先选择治疗病情更严重的患者,并减轻新型冠状病毒肺炎给卫生系统带来的负担,政府设立了疾病严重程度分级体系。省级和市级患者诊治团队的医护人员依据患者脉搏、收缩压、呼吸频率、体温和意识程度将患者分成不同的级别。中症、重症、危重症患者将被立即送至病房或负压隔离病房以接受住院治疗,轻症患者则会被送往全国 16 家指定机构进行监控。

当地状况

大邱市和庆尚北道省的病死率 (1.6%; 124/7756) 高于全国其他地区 (0.5%; 7/1485)。

相关变化

2020 年 2 月 25 日至 3 月 26 日期间, 大邱市和庆尚北道省每名新型冠状病毒肺炎患者的负压隔离病房使用率低于 0.15。同一期间,该国其他地区的该比率从 5.56 降至 0.63。实施分级体系之前, 51 例死亡病例中有 8 例 (15.7%) 发生于家中或从家转移至医疗机构的路上。

经验教训

应优先根据患者危重程度对其归类,从而减轻卫生系统的负担并降低病死率。

Резюме

Проблема

Всплеск случаев заболевания коронавирусом 2019 г. (COVID-19) поразил систему здравоохранения Республики Корея.

Подход

Правительство создало систему классификации тяжести заболевания, чтобы помочь работникам здравоохранения установить приоритетность лечения пациентов с более тяжелыми заболеваниями и снизить нагрузку на системы здравоохранения, обусловленную COVID-19. Персонал сферы здравоохранения в группах по ведению пациентов на уровне городов и провинций классифицировал пациентов по различным категориям в зависимости от пульса пациента, систолического артериального давления, частоты дыхания, температуры тела и уровня сознания. Пациенты, у которых тяжесть заболевания была классифицирована как умеренная, тяжелая и очень тяжелая, были незамедлительно распределены по койкам или изоляторам с отрицательным давлением для госпитализации, в то время как пациенты с легкими симптомами находились под наблюдением в 16 назначенных учреждениях по всей стране.

Местные условия

Показатели летальности были выше в городе Тэгу и провинции Кёнсан-Пукто (1,6%; 124/7756), чем в остальной части страны (0,5%; 7/1485).

Осуществленные перемены

С 25 февраля по 26 марта 2020 года соотношение изоляторов с отрицательным давлением на пациента с COVID-19 было ниже показателя в 0,15 в городе Тэгу и провинции Кёнсан-Пукто. В остальной части страны показатель указанного соотношения за тот же период снизился с 5,56 до 0,63. До введения в действие системы классификации 8 случаев смерти (15,7%) из 51 происходили дома или во время транспортировки пациентов из их домов в медицинские учреждения.

Выводы

Классификация пациентов по степени тяжести заболевания должна стать приоритетной мерой для облегчения нагрузки на систему здравоохранения и снижения показателей летальности.

Introduction

On 30 January 2020, the Director-General of the World Health Organization declared that the outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) constituted a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.1 By 15 August 2020, the global number of confirmed cases had increased to 21 million and the number of deaths had reached 755 566, translating into a case fatality rate of 3.6%.2

During an outbreak, the case fatality rate will depend on several factors, such as the demography of infected people, the number of infected people with a confirmed diagnosis and the health system’s capacity to cope with a rapid increase of cases.3 Thus, the case fatality rate varies among countries. For example, on 15 August the case fatality rate was far higher in France (15.2%; 30 275/198 876) than in the Republic of Korea (2.0%; 305/15 039).2 Trying to keep the number of COVID-19 cases below the health system’s capacity of coping with such cases is one important strategy to keep the case fatality rate low.

In the Republic of Korea, the rapid surge of COVID-19 cases in the Gyeongsangbuk-do province, and especially in the city of Daegu, overwhelmed the local health system, leading to some patients having no choice but to wait at home for a hospital bed, or to be transferred to another area. On 26 March, these two areas had reported 83.9% (7756/9241) of all the confirmed cases in the country. The affected areas also reported a higher case fatality rate compared with the rest of the country – 1.6% (124/7756) versus 0.5% (7/1485), respectively.4 To ease the burden on the health system, the government implemented a disease severity classification system to identify the COVID-19 patients needing care. Here, we describe this classification system and analyse the relationship between the number of negative-pressure isolation rooms and COVID-19 deaths.

Local setting

In the Republic of Korea, the health-care resources are evenly distributed across the country and almost the entire population is covered by a single-payer national health insurance.5 This single-payer setting enables the government to swiftly decide on health policies. Before the outbreak, there were 1027 negative-pressure isolation rooms in the country, covering 52 million people.6

On 20 January 2020, the first case of COVID-19 was detected in the country, when a woman from Wuhan, China, was tested positive upon her arrival at Incheon International Airport, Seoul. In the month after the first case was detected, the cumulative number of cases slightly increased in the country. However, after the Shincheonji Church event on 18 February, the number of cases suddenly increased among its members and non-members who were infected by a member of this church.7 Until 1 March, 87.3% (3260/3736) of COVID-19 cases were directly or indirectly related to the church and concentrated in the city of Daegu and the Gyeongsangbuk-do province.4 The first COVID-19 death was reported on 20 February and the number of accumulated deaths has continuously increased after the cases surged and accumulated.4

Approach

On 1 March 2020, the government adopted a test, trace, treat strategy to cope with the outbreak.8 From the initial stage of the outbreak, the government made every effort to detect as many infected people as possible, to trace suspected cases using epidemiological investigation and to treat all people with a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis.8

The health system response the government adopted can be summarized as follows.8–10 First, the government secured health-care or other resources to detect, isolate and monitor people with clinical symptoms indicative of COVID-19 or having a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis, and to treat patients with COVID-19. For instance, in cooperation with pharmaceutical companies the government promptly approved and adopted a diagnosis kit after Chinese authorities released the genetic sequences of the virus. Second, the government designated 74 hospitals dedicated to COVID-19 patients and secured 7500 beds in preparation for a surge in confirmed cases. Third, the government established a system to classify disease severity. This system was put in place to help health-care workers prioritize treatment for patients with more severe disease and to decrease the burden on health systems caused by COVID-19.8 On 1 March, the government published a guideline on how to classify confirmed cases into four categories: mild, moderate, severe, and very severe disease. After a person received a confirmed diagnosis, health-care staff in city- and provincial-level patient management teams classified the patients into the different categories according to the patient’s pulse, systolic blood pressure, respiratory rate, body temperature and level of consciousness (Table 1).11 Patients categorized as having moderate, severe and very severe disease were promptly assigned to beds or negative-pressure isolation rooms for hospital treatment, while patients with mild symptoms were monitored in 16 designated facilities across the country, most of which are residential training centres of public institutions and private companies.8

Table 1. Disease severity classification system for COVID-19, Republic of Korea, 2020.

| Criteria | Score |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Pulse, beats per min | 51–100 | 41–50 or 101–110 | ≤ 40 or 111–130 | ≥ 131 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 101–199 | 81–100 | 71–80 or ≥ 200 | ≤ 70 |

| Respiratory rate, breaths per min | 9–14 | 15–20 | ≤ 8 or 21–29 | ≥ 30 |

| Body temperature, °C | 36.1–37.4 | 35.1–36.0 or ≥ 37.5 | ≤ 35.0 | NA |

| Level of consciousness | Normal | Voice reaction | Pain reaction | Non-reaction |

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; NA: not applicable.

Notes: Patients with a total score of 0–4 were classified as mild cases, moderate cases had a total score of 5–6, and severe and very severe cases had a score ≥ 7. Very severe cases were patients needing renal replacement therapy or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

To analyse the burden of COVID-19 on the health system’s capacity and its influence on COVID-19 deaths, we retrieved data from cases by date of illness onset of COVID-19 from 20 January to 26 March 2020 from the website of the Ministry of Health and Welfare.4 We separated the patients into two groups based on their residence: those living in the city of Daegu or the Gyeongsangbuk-do province and those living elsewhere in the country. We used data on the number of negative-pressure isolation rooms per identified cases of COVID-19 to measure the burden of COVID-19 on the health system.

Relevant changes

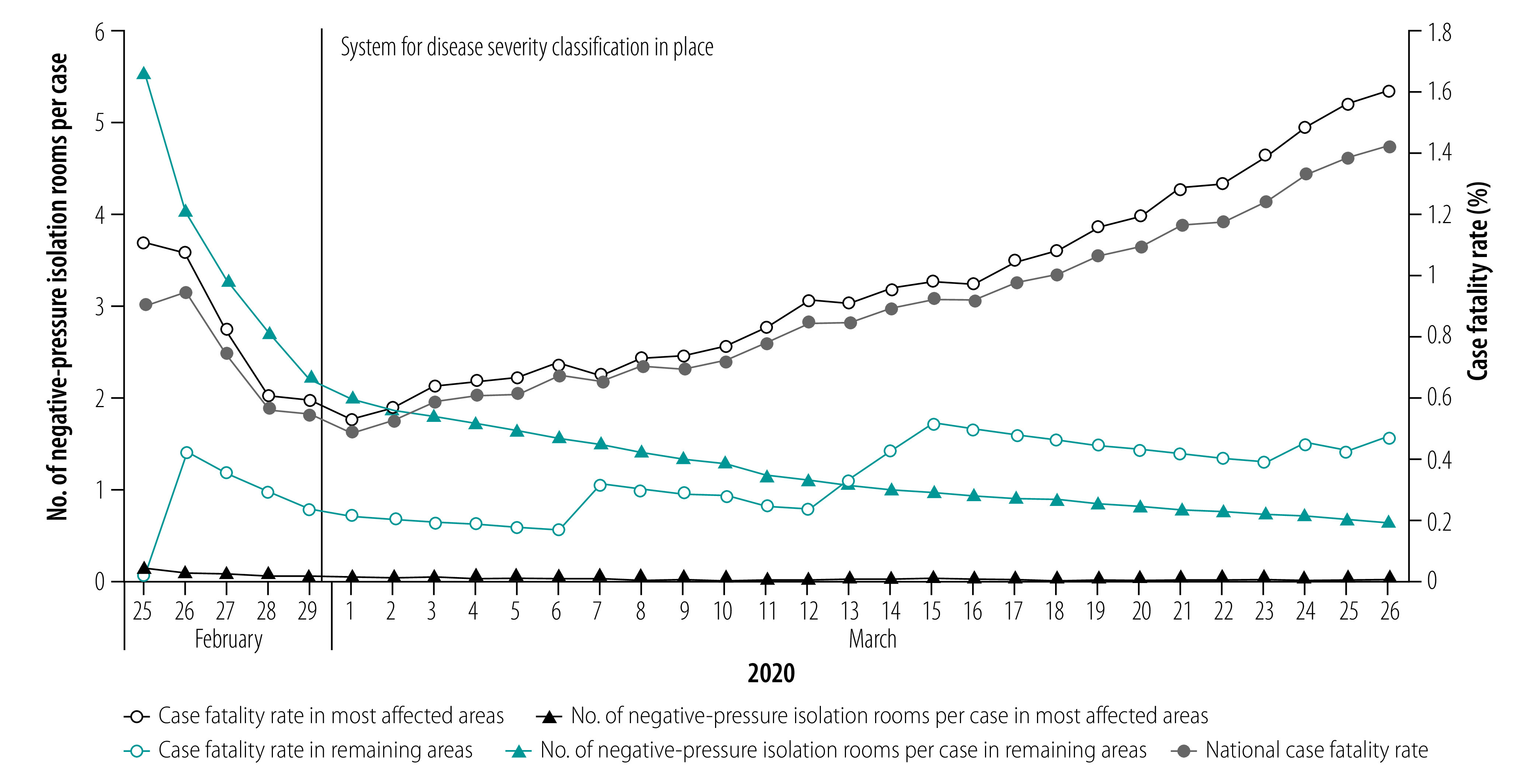

The changes in number of negative-pressure isolation rooms per COVID-19 patient and the case fatality rate is shown in Fig. 1. In areas not heavily affected by the outbreak, the number of negative-pressure isolation rooms per COVID-19 patient decreased from 5.56 on 25 February to 0.63 on 26 March. During the same period, the case fatality rate increased from 0.0% (0/169) to 0.5% (7/1485) in the areas not heavily affected by the outbreak. In the most affected areas, the health system was already overwhelmed on 25 February, with 0.12 negative-pressure isolation rooms per COVID-19 patient. The situation worsened and by 26 March there were only 0.01 rooms per patient. While the case fatality rate improved from 1.1% (8/724) on 25 February to 0.5% (17/3260) on 1 March, the rate was highest on 26 March (1.6%; 124/7756).

Fig. 1.

The capacity burden of COVID-19 and its outcomes in health systems in Republic of Korea, 25 February to 26 March 2020

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019.

Note: The most affected areas were in the city of Daegu and the Gyeongsangbuk-do province.

We also found that, from the onset of the outbreak to 8 March, out of the 51 deaths across the country, eight (15.7%) deaths occurred at home or during transfer from home to health-care institutions. However, no deaths have occurred outside a health-care facility since 8 March, which was 1 week after the government introduced the classification system.

Lessons learnt

After the classification system was in place, transferring patients with severe disease to health-care facilities in less affected areas became less common. Furthermore, isolating patients with mild symptoms in designated facilities protected the patients’ close contacts from being infected. Other efforts by the government, such as providing more resources to the affected area, also helped in controlling the outbreak.12

Based on the analysis, we learnt that a potential shortage of hospital beds, including negative-pressure isolation rooms, might lead to an increased case fatality rate. The affected area has a similar number of negative-pressure isolation rooms and beds in the intensive care unit per 1000 persons and an even higher number of hospital beds per 1000 persons compared to other areas. However, a surge in confirmed cases led to the affected area having a temporary shortage of hospital beds. Moreover, we observed that during the initial spread of the virus, deaths at home or during transfer from home to health-care institutions occurred. This finding implies that once a patient classification and referral system is established, deaths from COVID-19 can be reduced (Box 1).

Box 1. Summary of main lessons learnt.

The government’s swift response was important in preventing a surge in confirmed cases leading to a shortage of beds.

During an outbreak, the burden on a health system’s capacity is closely associated with the case fatality rate.

A treatment system based on severity of disease to place priority on more severe cases helps with decreasing the burden on health systems.

Many countries are struggling to cope with the pandemic, and this problem is being aggravated by a lack of resources. In this context, experiences from the Republic of Korea could be used to illustrate ways in which to tackle the outbreak of COVID-19. Securing diagnostic kits, beds and health-care provision, as well as facilities dedicated to patients with COVID-19 across the country, are essential to detect cases, to isolate and monitor suspected cases, and to provide adequate health-care services. Furthermore, when health-care resources are lacking, measures to decrease the burden on health systems are needed. This study indicates that the burden on a health system’s capacity is associated with the case fatality rate, and suggests that allocating patients according to their disease severity should be a prioritized measure.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov) [cited 2020 Aug 11].

- 2.WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/ [cited 2020 Aug 11].

- 3.Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020 May 12;323(18):1775–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coronavirus disease-19, Republic of Korea. Sejong City: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2020. Korean. Available from: http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/bdBoardList_Real.do?brdId=1&brdGubun=13&ncvContSeq=&contSeq=&board_id=&gubun= [cited 2020 Aug 11].

- 5.Republic of Korea health system review. Manila: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Number of negative-pressure isolation rooms in Republic of Korea. Seoul: Yonhap News; 2020. Korean. Available from: https://www.yna.co.kr/view/GYH20200220000200044 [cited 2020 Oct 27].

- 7.Introvigne M, Fautré W, Šorytė R, Amicarelli A, Respinti M. Shincheonji and the COVID-19 epidemic: sorting fact from fiction. J CESNUR. 2020;4(3):70–86. doi: 10.26338/tjoc.2020.4.3.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.All about Korea’s response to COVID-19. Seoul: Ministry of Foreign Affairs; 2020. Available from: http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/en/infoBoardView.do?brdId=14&brdGubun=141&dataGubun=&ncvContSeq=3855&contSeq=3855&board_id=&gubun= [cited 2020 Aug 11].

- 9.Ministry of Science, ICT. How we fought COVID-19: a perspective from Science & ICT. Seoul: Ministry of Foreign Affairs; 2020. Available from: http://www.mofa.go.kr/eng/brd/m_22591/view.do?seq=28&srchFr=&srchTo=&srchWord=&srchTp=&multi_itm_seq=0&itm_seq_1=0&itm_seq_2=0&company_cd=&company_nm=&page=1&titleNm [cited 2020 Aug 11].

- 10.Central Disaster and Safety Countermeasure Headquarters. Korea’s response to COVID-19 and future direction. Seoul: Ministry of Foreign Affairs; 2020. Available from: http://www.mofa.go.kr/eng/brd/m_22591/view.do?seq=11&srchFr=&srchTo=&srchWord=&srchTp=&multi_itm_seq=0&itm_seq_1=0&itm_seq_2=0&company_cd=&company_nm=&page=1&titleNm [cited 2020 Aug 11].

- 11.Central Disaster Management Headquarters. [Guidelines for the Operation of COVID-19]. Sejong City: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2020. Korean. Available from: http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/upload/viewer/skin/doc.html?fn=1597836948622_20200819203549.pdf&rs=/upload/viewer/result/202010/ [cited 2020 Aug 11].

- 12.Kim M, Lee J, Park J, Kim H, Hyun M, Suh Y, et al. Lessons from a COVID-19 hospital, Republic of Korea. Bull World Health Organ. 2020;98(12):842–48. doi: 10.2471/BLT.20.261016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]