Abstract

Objective

This study aims to investigate the occurrence of nicotine dependence following the achievement of previous smoking milestones (initiation, weekly, and daily smoking).

Method

Analyses are based on data from The National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent, a nationally representative face-to-face survey of 10,123 adolescents (age 13–17) conducted between 2001 and 2004.

Results

Among adolescents who had ever smoked (36.0%), 40.7% reached weekly smoking levels and 32.8% had reached daily smoking. Approximately one in five adolescents who had ever smoked (19.6%) met criteria for nicotine dependence. An earlier age of smoking initiation, a shorter time since the onset of smoking and faster transitions among smoking milestones were independently associated with the onset of daily smoking and nicotine dependence.

Conclusions

These findings shed new light on the course of smoking and nicotine dependence during adolescence by demonstrating a rapid transition across smoking stages for those most at risk for the development of chronic and dependent use.

Introduction

As the leading cause of preventable death worldwide [1], cigarette smoking accounts for at least 30% of all cancer deaths and remains a major cause of heart disease, emphysema, and stroke [2]. To date, smoking interventions have been overwhelmingly focused on the prevention of smoking initiation or, alternately, on the treatment for heavy dependent use. However, traditional accounts of the natural history of smoking have suggested that the onset of nicotine dependence follows a progressive series of milestones that also include intermediary stages of monthly [3], weekly [4], and daily use [4, 5]. With the exception of the link between age of smoking initiation and the likelihood of daily smoking or nicotine dependence [6], little is known about how the age of achievement of and speed of transitions between the different stages is associated with the risk of subsequent smoking milestones. Estimating these temporal dynamics as well as their association with the development of nicotine dependence may provide more malleable targets for further reductions in smoking prevalence.

Through previous work on the adult National Comorbidity Survey-Replication, we examined smoking transitions based on retrospective reports across adulthood, demonstrating that individuals reporting a faster transition between early smoking milestones were more likely to progress to both daily smoking and nicotine dependence, and that the risk for each smoking transition was highest within the year following the onset of the preceding milestone [4]. Given that adults are often asked to recall the timing of events that may have occurred decades before, reports past early adulthood are particularly subject to error [7]. Furthermore, since smoking a first cigarette takes place almost exclusively prior to age 18 and interventions targeting the adolescent population hold the greatest promise for preventing the development of dependent smoking, a more detailed understanding of the course of these stages in the adolescent population is a crucial public health need.

The National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent supplement (NCS-A) is the first nationally representative study to allow an evaluation of the association between the age of achievement of and speed of transition among major smoking milestones and onset of nicotine dependence in adolescents. In the present study, we estimate: (1) the occurrence of nicotine dependence following the achievement of previous smoking milestones (initiation, weekly, and daily smoking) and (2) the association between age of achievement of and speed of transitions between smoking milestones and risk for regular smoking and nicotine dependence.

Method

Participants and Study Procedures

The NCS-A is a nationally representative face-to-face survey of 10,123 adolescents (13–17 years, mean age=15.2; SE, 0.06) in the continental USA performed between February 2001 and January 2004 in a dual-frame sample that included a household subsample and a school subsample. The overall NCS-A adolescent response rate combining the two subsamples was 82.9%. Comparisons of sample and population distributions on census sociodemographic variables, and in the school sample on school characteristics, documented only minor differences that were corrected with poststratification weighting. Written informed consent from a parent-or-parent surrogate and written informed assent from the adolescent were obtained. The parent or caregiver completed a self-administered questionnaire that provided information on family demographic characteristics and a comprehensive set of measures regarding the target adolescent and his/her parents or caregivers [8]. The procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committees of both Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan. A more detailed description of the NCS-A measures, sample design and field procedures, and lifetime prevalence rates is presented elsewhere [8, 9].

Measures

Tobacco Module

Lifetime smoking behavior and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) nicotine dependence were based on responses to the CIDI 3.0, a fully structured lay interview modified for the NCS-A and described in detail elsewhere [8]. Administration of the smoking module was based on a gate question that inquired whether the adolescent had “ever smoked a cigarette, cigar or pipe, even a single puff”. Positive responses to this question were followed with a detailed assessment of lifetime smoking behavior including onset of ever, weekly, and daily smoking. Respondents who reported reaching weekly smoking were asked about the DSM-IV symptoms of nicotine dependence (i.e., tolerance, withdrawal, or smoking to avoid or reduce withdrawal, smoking in larger amounts or longer than intended, persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down, great deal of time spent to obtain, use or recover from smoking, activities given up or reduced, and smoking despite physical or psychological problems caused or exacerbated by smoking). Those meeting DSM-IV criteria at any point in their lifetime were considered to be nicotine dependent.

Transition Variables

The age of achievement of smoking milestones was based on reported age of onset of smoking initiation (“How old were you the very first time you smoked even a puff of a cigarette, cigar or pipe?”), weekly smoking (“How old were you the very first time you smoked tobacco at least once a week for at least two months?”), daily smoking (“How old were you the first time you smoked tobacco every day, or nearly every day for a period of at least two months?”), and nicotine dependence (“How old were you the first time you had any of these problems?”). Variables accounting for speed of transitions between smoking milestones were created by subtracting age at reaching an earlier smoking milestone (e.g., smoking initiation) from age at reaching a later milestone (e.g., weekly smoking).

Sociodemographic Correlates

Sociodemographic correlates include gender, age (defined by age at interview in categories 13–14, 15–16, and 17–18 years), sex, race–ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic black, other and non-Hispanic white), urban residence (metro, other urban, rural), poverty income ratio (calculated by dividing family income by a poverty threshold specific to family size; <1.5 lowest family income, ≤3, ≤6, ≥6 highest family income), parent or caregiver marital status (married/cohabiting, previously married (divorce/widowed), never married, unknown) and highest level of education of either parent (<high school, high school, some college, college graduate).

Data Analytic Procedure

Cumulative incidence curves of ever, weekly, and daily smoking and the transition to nicotine dependence were obtained by means of PROC LIFETEST in SAS, version 9.1.3 which appropriately censors the data to account for the fact that transition ages of the sample are only partially known given that youth have moved through different periods of risk for the onset and escalation of smoking. Multivariate logistic regression analyses estimated the associations between (1) demographic characteristics and achievement of each of the smoking milestones (ever, weekly, daily smoking and nicotine dependence) and (2) both age of achievement and speed of movement through the smoking milestones (controlling for demographic characteristics). Smoking milestones were included in the models as outcomes, while demographic characteristics and both the age of achievement and speed of transitions between smoking milestones were included as predictors. All standard errors and significance tests were estimated using the SURVEYLOGISTIC procedure to adjust for design effects. Speed of transitions were defined as the number of years since the onset of the earlier tobacco milestone up to the age of onset of later smoking milestone or age at interview (for censored cases). Covariates included gender, age, race–ethnicity, urban residence, poverty income ratio, parental marital status, and parent education.

Results

Prevalence and Sociodemographic Correlates of Smoking and Nicotine Dependence

Thirty-six percent (SE=0.7) of the US adolescent population reported smoking a puff or more of a cigarette, cigar, or pipe in their lifetime. Of those who had ever smoked, 40.7% (SE=1.2) had reached weekly smoking levels (population prevalence=14.6% SE 1.1) and 32.8% (SE=1.2) had reached daily smoking (population prevalence=11.8%, SE 0.9). Approximately one in five of those who had ever smoked (19.6%, SE 1.0) met criteria for nicotine dependence (population prevalence=7.0%, SE 0.4). The mean age of onset of each milestone was 12.2 years (SE 0.09) for smoking initiation, 13.5 (SE 0.11) for weekly smoking, 13.8 (SE 0.18) for daily smoking, and 14.5 (SE 0.26) for nicotine dependence. Although females showed a significantly later age of smoking initiation (mean=12.5, SE 0.12) compared to males (mean=12.0, SE 0.11), F=12.32, df 1, 42, p=0.0011, age of onset for the remaining smoking milestones did not differ by either gender or ethnicity. While the vast majority of adolescents reported achieving nicotine dependence in the same year or 1 or more years subsequent to the onset of both weekly and daily smoking, 7% of ever daily smokers reported that dependence preceded daily smoking.

The likelihood of ever smoking, as well as the likelihood of weekly smoking among ever smokers and daily smoking among ever and weekly smokers did not vary significantly by sex, poverty, or urbanicity (Table 1). However, strong effects were observed for race/ethnicity. Compared to White adolescents, Black youth had significantly lower rates of ever smoking, as well as progression to weekly and daily smoking among those who had ever smoked. Among youth who had ever smoked, Hispanic adolescents showed lower rates of daily smoking compared to White adolescents. Generally increasing rates were observed for each of these smoking stages with increasing age, and all stages were more prevalent among adolescents whose parents did not graduate from college, with the exception of transitions to daily smoking among weekly smokers. Parent/caregiver marital status was associated only with the prevalence of ever smoking, with significantly lower rates being observed among adolescents whose parents/caregivers were married/cohabitating compared to those whose parents’ marital status was unknown and those who were previously married. Once adolescents had reached either weekly or daily smoking levels, most individual or familial sociodemographic characteristics were unrelated to the probability of transition to nicotine dependence. Gender and age were exceptions with females more likely to transition to dependence from weekly and daily smoking than males, and 17–18 year olds more likely to transition to nicotine dependence from weekly smoking than younger adolescents.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic correlates of smoking stages among US adolescents (NCS-A)

| Correlates | Ever smoked (n = 10,123) | Weekly smoking among ever smokers (n = 3,622) | Daily smoking among ever smokers (n = 3,622) | Daily smoking among weekly smokers (n = 1,437) | Nicotine Dependence among weekly smokers (n = 1,437) | Nicotine dependence among daily smokers (n = 1,166) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | χ2 | OR | (95% CI) | χ2 | OR | (95% CI) | χ2 | OR | (95% CI) | χ2 | OR | (95% CI) | χ2 | OR | (95% CI) | χ2 | |

| Sex | – | |||||||||||||||||

| Female | 1.00 | – | 2.99 | 1.00 | – | 0.14 | 1.00 | – | 0.33 | 1.00 | – | 3.12 | 1.00 | – | 5.47a | 1.00 | _ | 3.97a |

| Male | 1.13 | (0.98–1.30) | 0.96 | (0.78–1.19) | 0.91 | (0.66–1.26) | 0.71 | (0.48–1.04) | 0.69 | (0.50–0.94) | 0.68 | (0.46–0.99) | ||||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 0.85 | (0.65–1.12) | 34.44c | 0.78 | (0.48–1.20) | 17.58b | 0.60 | (0.43–0.83) | 16.51b | 0.64 | (0.31–1.30) | 2.92 | 0.73 | (0.38–1.39) | 1.13 | 0.76 | (0.42–1.35) | 1.60 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.46 | (0.35–0.61) | 0.51 | (0.35–0.74) | 0.62 | (0.44–0.86) | 0.81 | (0.40–1.63) | 1.07 | (0.67–1.71) | 1.07 | (0.64–1.79) | ||||||

| Other | 0.74 | (0.56–0.99) | 0.72 | (0.52–1.00) | 0.63 | (0.28–1.40) | 0.42 | (0.13–1.39) | 0.97 | (0.41–2.31) | 1.40 | (0.50–3.89) | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | ||||||

| Age | ||||||||||||||||||

| 13–14 Years old | 0.21 | (0.17–0.26) | 253.38c | 0.30 | (0.21–0.42) | 50.69c | 0.00 | (0.00–0.01) | 132.19c | 0.10 | (0.06–0.18) | 61.97c | 0.25 | (0.14–0.44) | 22.53c | 1.21 | (0.60–2.43) | 0.41 |

| 15–16 Years old | 0.51 | (0.43–0.60) | 0.59 | (0.48–0.73) | 0.10 | (0.06–0.15) | 0.59 | (0.39–0.89) | 0.63 | (0.41–0.96) | 0.97 | (0.64–1.49) | ||||||

| 17–18 Years old | 1.00 | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | ||||||||

| Poverty income ratio | ||||||||||||||||||

| <1.5 | 1.21 | (0.99–1.48) | 6.35 | 1.00 | (0.74–1.35) | 2.03 | 0.70 | (0.40–1.26) | 5.60 | 0.74 | (0.36–1.55) | 5.87 | 0.49 | (0.27–0.90) | 5.54 | 0.56 | (0.31–1.00) | 4.39 |

| ≤3 | 1.14 | (0.91–1.43) | 0.85 | (0.59–1.23) | 0.88 | (0.57–1.36) | 1.39 | (0.79–2.43) | 0.79 | (0.44–1.43) | 0.66 | (0.35–1.25) | ||||||

| ≤6 | 0.94 | (0.80–1.11) | 1.10 | (0.88–1.38) | 1.15 | (0.88–1.49) | 1.47 | (0.89–2.43) | 0.90 | (0.58–1.40) | 0.80 | (0.51–1.26) | ||||||

| >6 | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | ||||||

| Urban | ||||||||||||||||||

| Metro | 1.01 | (0.88–1.15) | 0.82 | 0.90 | (0.63–1.30) | 2.85 | 0.93 | (0.65–1.32) | 7.52a | 1.13 | (0.59–2.19) | 0.19 | 1.17 | (0.80–1.71) | 0.95 | 1.22 | (0.82–1.82) | 1.12 |

| Other urban | 0.93 | (0.77–1.11) | 0.78 | (0.58–1.06) | 0.67 | (0.49–0.91) | 1.03 | (0.54–1.98) | 1.18 | (0.81–1.71) | 1.26 | (0.78–2.03) | ||||||

| Rural | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | ||||||

| Parental education | ||||||||||||||||||

| ≤High school | 1.52 | (1.18–1.95) | 42.15c | 1.82 | (1.33–2.47) | 20.02b | 2.28 | (1.52–3.42) | 18.99b | 1.84 | (1.08–3.16) | 6.21 | 0.83 | (0.42–1.66) | 3.33 | 0.74 | (0.40–1.37) | 2.16 |

| High school | 1.82 | (1.51–2.20) | 1.59 | (1.19–2.12) | 1.84 | (1.16–2.91) | 1.90 | (0.99–3.63) | 1.41 | (0.89–2.22) | 1.25 | (0.79–1.99) | ||||||

| Some college | 1.67 | (1.33–2.08) | 1.73 | (1.27–2.35) | 1.85 | (1.23–2.77) | 1.37 | (0.68–2.74) | 1.22 | (0.72–2.07) | 1.22 | (0.70–2.13) | ||||||

| College graduate | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | ||||||

| Parent/caregiver marital status | ||||||||||||||||||

| Married/cohabitating | 1.00 | – | 15.14b | 1.00 | – | 4.07 | 1.00 | – | 0.55 | 1.00 | – | 5.40 | 1.00 | – | 2.17 | 1.00 | – | 0.87 |

| Previously married | 1.36 | (1.05–1.77) | 1.51 | (1.01–2.25) | 1.20 | (0.66–2.19) | 1.67 | (0.65–4.28) | 1.65 | (0.83–3.31) | 1.30 | (0.67–2.51) | ||||||

| Never married | 1.48 | (0.97–2.27) | 1.03 | (0.45–2.32) | 1.24 | (0.53–2.88) | 0.78 | (0.25–2.46) | 1.07 | (0.34–3.32) | 1.01 | (0.30–3.42) | ||||||

| Unknown marital status | 1.20 | (1.06–1.36) | 1.17 | (0.91–1.50) | 1.04 | (0.77–1.39) | 0.84 | (0.55–1.28) | 1.13 | (0.78–1.65) | 1.14 | (0.78–1.67) | ||||||

OR significant at 0.05 level, two-tailed test

OR significant at 0.01 level, two-tailed test

OR significant at >0.001 level, two-tailed test

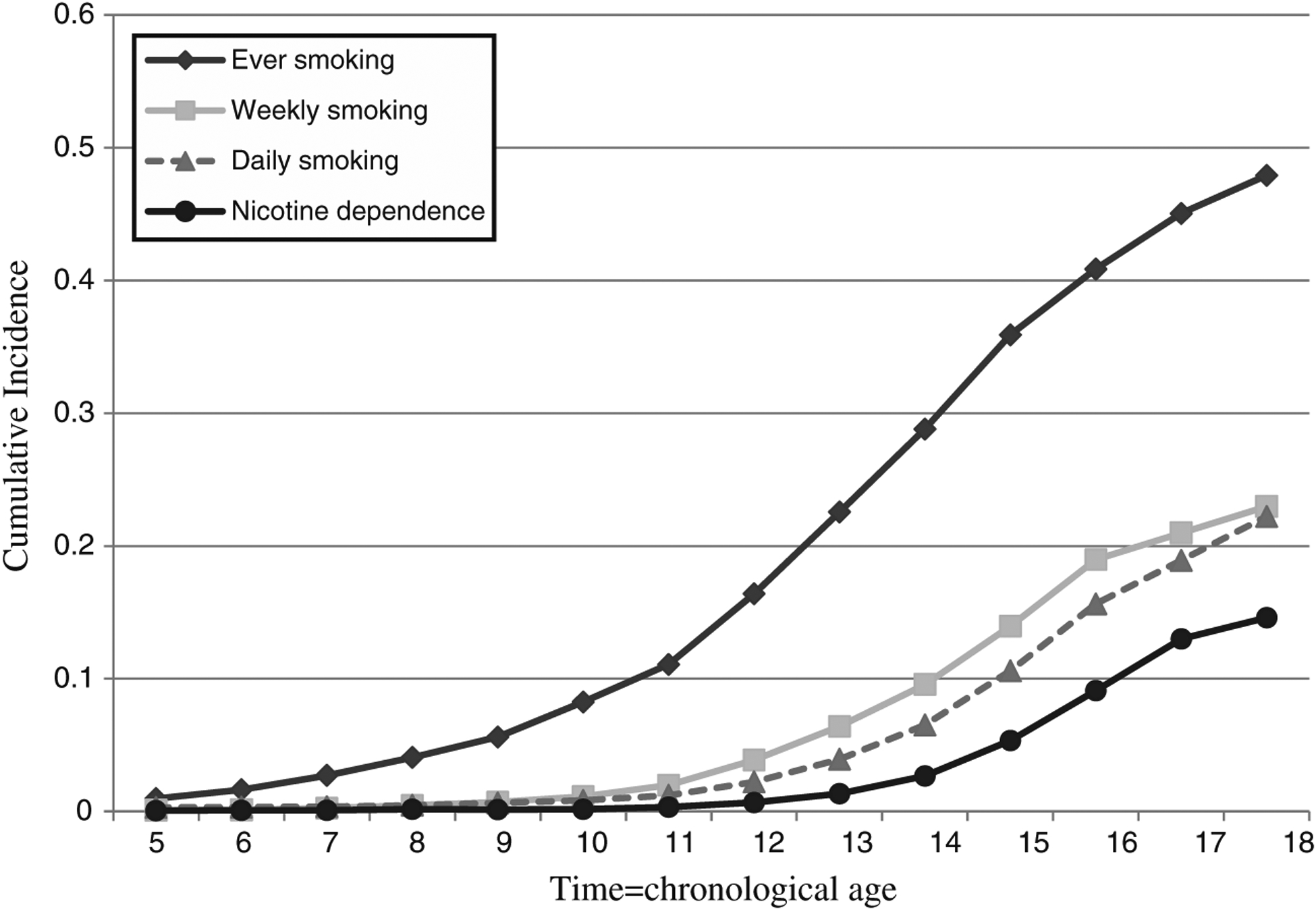

Cumulative Incidence Curves for Achievement of and Speed of Smoking Transitions

Figure 1 presents the cumulative incidence curves of each smoking milestone according to chronological age (i.e., the reported age of onset of each smoking milestone). The cumulative probability of attaining each smoking milestone shows an increase beginning at age 11. Figure 2 presents the cumulative probability of attaining each smoking milestone according to time from achievement of a previous milestone (i.e., the difference between ages of onset for the smoking milestone of interest and the age of onset for the previous milestone). Here, the cumulative probability of weekly and daily smoking increased sharply during the first 2 years following smoking initiation; the rate of increase is slower to 3 years and levels off thereafter. More than half of the transitions to daily smoking and nicotine dependence occurred in the first year following the onset of weekly smoking with increases in cumulative probability continuing to 3 years, again leveling off thereafter.

Fig. 1.

Cumulative incidence curves of ever, weekly, daily smoking and nicotine dependence in the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent (time=chronological age)

Fig. 2.

Cumulative incidence curves of ever, weekly, daily smoking and nicotine dependence in the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent (time=years since onset of previous smoking milestone)

Age of Achievement and Speed of Transitions Predicting Smoking Milestones

After controlling for gender, age cohort, race–ethnicity, urban residence, poverty, parent marital status, and parent education, multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed that an earlier age of smoking initiation, OR 0.90 (0.86–0.95) significantly predicted the transition to weekly smoking among ever smokers. When predicting daily smoking, an earlier age of smoking initiation, OR 0.28 (0.22–0.35) and a faster transition between smoking initiation and weekly smoking, OR 0.25 (0.19–0.31), were each independently associated with an increased likelihood of transitioning to daily smoking among those who had ever smoked.

When predicting nicotine dependence among adolescents who had reached weekly smoking an earlier age of smoking initiation, OR 0.71 (0.60–0.83), a shorter time between smoking initiation and weekly smoking OR 0.78 (0.65–0.93), and a faster transition between weekly and daily smoking OR 0.67 (0.56–0.78), each independently predicted an increased likelihood of nicotine dependence. When entering each of the transitions between smoking milestones into the model as discrete-time variables (i.e., age converted to individual yearly units), the transition to nicotine dependence was more likely to occur in the year following the smoking initiation, and the onset of weekly smoking, than in subsequent years following these transitions.

Each of the significant associations were consistently found within demographic subgroups when models were reestimated individually by gender, age cohort, race–ethnicity, urban residence, poverty, parent marital status, and parent education.

Discussion

This investigation documented the natural course of smoking in the first nationally representative sample of US adolescents capable of evaluating transitions between initiation, weekly smoking, daily smoking, and nicotine dependence. The key findings are that more than a third of adolescents reported smoking a puff or more in their lifetime. Of those who had ever smoked, 40.7% had reached weekly smoking levels and 32.8% had reached daily smoking. Approximately one in five of those who had ever smoked met criteria for nicotine dependence. Race/ethnicity, age, and parental education demonstrated strong associations with the risk of ever smoking, or transitions to weekly or daily smoking. However, once weekly or daily smoking milestones were achieved, these sociodemographic variables were not associated with the onset of nicotine dependence. Importantly, younger age at achievement of a milestone and faster transitions between smoking milestones were found to be associated with increased risk for weekly smoking, daily smoking, and nicotine dependence, and the risk for attaining each of these milestones was highest within the year following the onset of the preceding milestone.

Overall, rates of ever smoking and daily smoking in the NCS-A mirror those described in previous studies based on nationally representative samples of adolescents [10]. The rate of DSM-IV nicotine dependence was found to be 7% in the present NCS-A sample, to our knowledge the first survey of US adolescents to establish prevalence based on formal DSM-IV criteria. Previous epidemiological studies based on representative adult samples have found that between one third to one half of daily smokers develop nicotine dependence at some point in their lives [4, 11]. In the present sample, 19% of daily adolescent smokers had already transitioned to nicotine dependence. Given that the transition was more likely to occur in the year following the onset of daily smoking, it is likely that this rate may double as the cohort moves through adolescence and into young adulthood.

The findings confirm previous observations from nationally representative samples demonstrating that the progression across initial smoking stages is associated with race/ethnicity, age, and parental education [12]. However, the present study advances our knowledge of the natural course of smoking behavior by demonstrating the effects of speed of transitions on the onset of major smoking milestones. We confirm previous evidence that adolescents who initiate smoking at a younger age have an increased risk of developing nicotine dependence and chronic smoking [13, 14] and provide additional information indicating that the speed of transitions between smoking stages is predictive of achieving each of the milestones examined. These analyses move beyond traditional approaches that have focused largely on dependent smoking, or that have examined risk factors for individual stages of use without regard to the importance of temporal dynamics. In this way, they reveal the role of speed of transitions between smoking stages during the key age range for the onset of smoking and nicotine dependence.

The achievement of a higher smoking milestone was also consistently more frequent in the year most proximal to the onset of the preceding milestone. Such findings underscore both the rapid progression of many adolescents towards dependent smoking as well as the very limited time period in which prevention or intervention may halt progression to subsequent milestones. Further, the speed of transition between initiation and weekly use was also found to be associated with daily smoking and nicotine dependence. The fact that speed of transitions between smoking initiation, weekly, and daily smoking were independently associated with the achievement of daily smoking and nicotine dependence milestones further confirms the importance of this early course in establishing who will become a chronic smoker and confirms retrospective reports based on the NCS-R [4]. The findings regarding speed of transition also add to accumulating evidence that heavy/prolonged exposure may not be the primary influence in the development of addiction. That is, given that onset of nicotine dependence was often rapid, it is likely that other factors beyond heaviness of exposure are driving this progression, an idea that has been supported in previous research [3, 15]. This rapid transition from use to dependence seems to be most common for psychostimulants including both tobacco and cocaine [16–19]. In contrast, alcohol and marijuana use have failed to show this rapid development of dependence [18]. Certainly, further research is needed to elucidate the biological and sociocultural bases for individual variability in the progression of smoking behavior.

Strengths and Limitations

Overall, the NCS-A afforded a number of strengths in terms of examining the natural course of smoking behavior. First, the present findings characterize nationally representative estimates during the period most critical to smoking initiation and progression that are likely more representative of the total population of adolescents than previously collected school-based surveys [10, 20], since the household module of the NCS-A is designed to include school drops outs who are more likely to be heavy smokers and nicotine dependent than high school students. Second, the NCS-A gathered information on weekly smoking and the onset of nicotine dependence, both milestones that have not been assessed in comparable epidemiologic surveys. Further, our use of the survival framework accounted for the fact that not all individuals had moved through the age of risk for each of the outcomes of interest.

The present findings should also be considered within the context of study limitations. First, only those who smoked at least weekly were asked about symptoms of nicotine dependence, thus limiting our ability to evaluate dependence among adolescents who had not yet reached weekly smoking [15]. Second, the retrospective reporting of age of reaching smoking milestones, even when reported more proximally as is the case in this young sample, is subject to error. For example, a frequent criticism of cross-sectional research concerns the fact that respondents report past events as having occurred closer to the time of interview than is accurate [7]. Third, while cumulative incidence curves appropriately censored the data to account for the fact that transition ages of the sample are only partially known given that youth have moved through different periods of risk for the onset and escalation of smoking, logistic regression analyses were not able to account for censoring.

This research adds to accumulating evidence that for many adolescents, smoking initiation represents the beginning of a process that leads rapidly to established smoking and nicotine dependence. Therefore, more targeted intervention aimed at adolescents and young adults based on their previous exposure to smoking may be warranted. The findings from international twin studies of adults [21] and adolescents [22] that environmental factors have strong influence on early stages of smoking, whereas genetic factors contribute to later stages of smoking, particularly dependence, make an even more compelling case for intervention before established patterns of smoking emerge. Currently, the malleability of smoking behavior during this uptake process is unknown, but may represent an appropriate point of intervention [23, 24].

Acknowledgments

The National Comorbidity Survey Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) and the larger program of related NCS surveys are supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (U01-MH60220). Data analysis and interpretation, manuscript preparation, review and approval were supported an Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Mental Health (Z01 MH002808-08; Merikangas, He); grants R01DA022313 and R21DA024260 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Dierker), and P50DA098262 awarded to Penn State University. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or the US Government.

The Tobacco Etiology Research Network (TERN) includes Richard Clayton, David Abrams, Robert Balster, Linda Collins, Ronald Dahl, Brian Flay, Gary Giovino, Jack Henningfield, George Koob, Robert McMahon, Kathleen Merikangas, Mark Nichter, Saul Shiffman, Stephen Tiffany, Dennis Prager, Melissa Segress, Christopher Agnew, Craig Colder, Lisa Dierker, Eric Donny, Lorah Dorn, Thomas Eissenberg, Brian Flaherty, Lan Liang, Nancy Maylath, Mimi Nichter, Elizabeth Richardson, William Shadel, and Laura Stroud.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.WHO. Report on the global tobacco epidemic: Implementing smoke-free environments. Geneva; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and economic costs—United States, 1995–1999 Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report; 2002. Report No.: 51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, Ockene JK, Rigotti NA, McNeill AD, et al. Measuring the loss of autonomy over nicotine use in adolescents: The DANDY (Development and Assessment of Nicotine Dependence in Youths) study. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 2002;156(4):397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dierker L, He J, Kalaydjian A, Swendsen J, Degenhardt L, Glantz M, et al. The importance of timing of transitions for risk of regular smoking and nicotine dependence. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 2008(36):87–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.SAMHSA. Office of Applied Studies, National Survey on Drug Use and Health; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baron-Epel O, Haviv-Messika A. Factors associated with age of smoking initiation in adult populations from different ethnic backgrounds. European Journal of Public Health 2004;14(3):301–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson EO, Schultz L. Forward telescoping bias in reported age of onset: An example from cigarette smoking. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 2005;14(3):119–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merikangas K, Avenevoli S, Costello E, Koretz D, Kessler R. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A): I. Background and measures. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009;48(367–379). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kessler R, Avenevoli S, Costello E, Green J, Gruber M, Heeringa S, et al. Design and field procedures in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent (NCS-A) Supplement. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2009; 18(2):69–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.CDC. Cigarete use among high school students: United States, 1991–2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2008;57(25):689–691 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anthony JC, Warner LA, Kessler RC. Comparative epidemiology of dependence on tobacco, alcohol, controlled substances, and inhalants: Basic findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Experimental & Clinical Psychopharmacology 1994;2(3):244–268. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kandel DB, Chen K. Extent of smoking and nicotine dependence in the United States: 1991–1993. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2000;2(3):263–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Everett S, Husten C, Kann L, Warren C, Sharp D, Crosset L. Smoking initiation and smoking patterns among US college students. Journal of American College Health 1999;48:55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Everett S, Warren C, Sharp D, Kann L, Husten C, Crossett L. Initiation of cigarette smoking and subsequent smoking behavior among US high school students. Preventive Medicine 1999; 29(5):327–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gervais A, O’Loughlin J, Meshefedjian G. Milestones in the natural course of onset of cigarette use among adolescents. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2006; 175(3):255–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Brien MS, Anthony JC. Risk of becoming cocaine dependent: Epidemiological estimates for the United States, 2000–2001. Neuropsychopharmacology 2005;30(5):1006–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Storr CL, Zhou H, Liang K-Y, Anthony JC. Empirically derived latent classes of tobacco dependence syndromes observed in recent-onset tobacco smokers: Epidemiological evidence from a national probability sample survey. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2004;6(3):533–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner FA, Anthony JC. From first drug use to drug dependence: Developmental periods of risk for dependence upon marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol. . Neuropsychopharmacology 2002;26(4):479–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ridenour T, Lanza S, Donny E, Clark D. Different lengths of times for progressions in adolescent substance involvement. Addictive Behaviors 2006;31(6):962–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2010. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madden P, Heath A, Pedersen N, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M, Martin N. The genetics of smoking persistence in men and women: A multicultural study. Behavior Genetics 1999;29:423–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rhee S, Hewitt J, Young S, Corly R, Crowley T, Stallings M. Genetic and environmental influences on substance initiation, use and problem use in adolescents. . Archives of General Psychiatry 2003;60:1256–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiore MC. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: A US Public Health Service Report. Journal of the American Medical Association 2000;283:3244–3254.10866874 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okuyemi KS, Harris KJ, Scheibmeir M, Choi WS, Powell J, Ahluwalia JS. Light smokers: Issues and recommendations. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2002: S103–S112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]