Abstract

Family-based interventions offer a promising avenue for addressing chronic negative family interactions that contribute to lasting consequences, including family violence and the onset and maintenance of mental health disorders. The purpose of this study was to conduct a mixed-methods, single group pre-post pilot trial of a family therapy intervention (N = 10) delivered by lay counselors in Kenya. Results show that both caregivers and children reported reductions in family dysfunction and improved mental health after the intervention. Point estimates represent change of more than two standard deviations from baseline for the majority of primary outcomes. Treated families also reported a decrease in harsh discipline, intimate partner violence, and alcohol-related problems. These results were corroborated by findings from an observational measure of family functioning and in-depth qualitative interviews. This study presents preliminary evidence of pre-post improvements following a family therapy intervention consisting of streamlined, evidence-informed family therapy strategies to target family dysfunction and mental health.

Keywords: Family therapy, Global mental health, Child and adolescent mental health, Kenya, Low- and middle-income countries

Chronic and negative family interactions pose major risks, leading to perpetration of family violence and the onset and maintenance of mental health disorders among children, adolescents, and adults (Repetti et al. 2002). These consequences are important global public health problems, as an estimated 10–20% of young people worldwide suffer from mental health disorders, many in low-and-middle income countries (LMICs; Kieling et al. 2011). Likewise, nearly one-quarter of people worldwide report childhood physical abuse, and one-third report childhood emotional abuse (Stoltenborgh et al. 2015). In Kenya, the site of the current study, 70% of males and 80% of females reported at least one type of maltreatment before age 18 (UNICEF 2012). Given these needs, it is essential to identify points of intervention to reduce risk factors at both the individual and family levels, particularly in places where mental health care is extremely scarce.

Family therapy interventions offer a promising avenue for achieving better outcomes for both families and their individual members simultaneously given how closely individual and family wellbeing are connected. While negative family factors—mistrust, maltreatment, parental mental health problems, and intimate partner violence—are associated with increased risk of child mental health disorders, positive communication, parental involvement, and monitoring emerge as protective for child mental health (Boudreault-Bouchard et al. 2013; Khasakhala et al. 2013; Vu et al. 2016). Therefore, treating family-level problems—replacing negative interaction patterns with positive processes—could serve to prevent, or even reverse, the severe downstream mental health consequences. To date, family-level interventions delivered in LMICs have shown promising results. Many are group-based parent training or family strengthening programs that focus on teaching behavioral skills to foster more positive interactions, especially between parents and children. Positive outcomes of these programs include improved parenting practices, family and parent–child communication, and child and adolescent psychosocial outcomes (Knerr et al. 2013; Mejia et al. 2012; Pedersen et al. 2019). However, most of these programs are focused primarily on prevention and teach standardized sets of foundational skills. This leaves a significant gap in family interventions in LMICs—the lack of more intensive, individualized interventions for families who are currently experiencing risky, negative interaction patterns across multiple parts of the family system.

Addressing complex family problems is at the core of family therapy theory and practice, which has a long history and evidence base from research in high-resource contexts (Carr 2009; Marvel et al. 2009). Family therapy approaches are likely be effective in LMICs as well, with Patterson et al. (2018) publishing a “call for increased awareness and action for family therapists” in the field of global mental health. Despite this, many barriers have led researchers and clinicians to stop short of using family therapy strategies in low-resource settings globally. First, they are traditionally dependent on cadres of professionals and functional mental healthcare systems—resources not available in many low resource contexts. In Kenya, for instance, there are 0.2 psychiatrists per 100,000 people (WHO 2019). Second, the limited number of available providers often focus on individual adult treatment and have very few opportunities for training in family-level interventions (Kieling et al. 2011; Patterson et al. 2018). Lastly, family therapy is often considered to require more clinical flexibility than other treatment modalities, making it more difficult to manualize than very structured, individual therapies targeting certain symptoms (Pote et al. 2003). Together, these characteristics have raised questions about feasibility and scalability.

While some challenges of implementing family therapy are unique, all mental health interventions carry challenges for sustainability and scalability in LMICs. Like family therapy, individual-level interventions are also developed in high-resource settings for delivery by trained professionals, but challenges have been addressed through streamlining evidence-based practices and task shifting—training non-professionals to provide treatment (Joshi et al. 2014). Task shifting has proven effective in diverse settings for a range of disorders and treatments, including child interventions (Murray et al. 2018; O’Donnell et al. 2014). It is therefore likely that task shifting can be applied to family therapy if adequate attention is given to identifying best practices for manualizing strategies that are often less standardized and to providing adequate training on the complexities of addressing relationship problems and treating multiple people at once.

The purpose of the current study was to pilot test an individualized, solution-focused, and modular family intervention in Kenya within a community-based task shifting delivery model. The intervention was designed to meet the needs of families with a diverse range of relationship problems. We implemented a delivery model in which lay counselors were recruited to deliver the intervention within their own communities to mirror the informal ways in which community members have already been reaching and advising families who are experiencing problems. Results include clinical changes across multiple target outcomes: family dysfunction, couples’ relationships and violence, harsh discipline of children, and individual child and caregiver mental health.

Method

We used a pre-post, single group design and mixed methods to examine change. The protocol was approved by ethical review boards at Duke University and Moi University (Kenya).

Setting and Participants

This study was conducted in two peri-urban communities near Eldoret, Kenya. Eldoret is the location of Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital, which provides mental healthcare services focused on inpatient treatment for serious mental illness, as well as limited outpatient services for individual treatment of common mental disorders. In Eldoret, and Kenya more broadly, training in family-based and child mental healthcare is in its infancy, and there is not yet a strong emphasis on community-based care.

In this study, lay counselors were community members with no prior mental health training, as we aimed to test a task shifting model that occurs outside of the health system and within existing community-based structures and practices. To recruit counselors, community leaders identified 23 trusted individuals from religious congregations and local civic leadership. We sought lay counselors who reported they already spent significant amounts of time serving as informal sources of support for families undergoing serious problems. Recruiting these “natural counselors” as the lay providers was central to implementation since they had already demonstrated overcoming challenges of stigma and confidentiality concerns within their current practices. We interviewed this cohort and invited a subset of 14 for training. Based on demonstration of clinical skills and knowledge of the intervention during training, as well as on continuing availability, a final group of 8 counselors delivered the treatment; this included one pair working as a husband-wife team. Counselors included 4 women and had an mean age of 45 years. The majority had attended at least part of secondary school (high school), and most were engaged in some type of part-time work. Each had a role in the community that facilitated their “natural counselor” position, such as pastor, youth group leader, or community “policymaker.” To mirror their existing, informal counseling routines as much as possible, counselors were asked to carry only 1–2 cases at a time, requiring roughly the same amount of time they were accustomed to spending. Given this, they were compensated for research activities that took additional time (e.g., surveys) but not for the counseling sessions themselves. A more detailed description of counselor characteristics, training, the delivery model, and implementation outcomes is in Puffer et al. (2019).

Counselors recruited families from their communities who they believed to exhibit persistent patterns of dysfunctional family interactions. They were asked to prioritize those with an adolescent between 12 and 17 years old with suspected behavioral or emotional concerns to allow for opportunities to pilot the parent–child and child mental health-focused modules. We asked counselors to use their typical methods of identifying families needing assistance and to invite families who they would typically counsel informally. However, they were asked not to recruit families who they had already counseled. In most cases, counselors drew from families they knew from their communities or religious congregations who had recently approached the counselor with a family concern or who had exhibited indicators that caused the counselor to be concerned (e.g., a child dropping out of school, a couple spending time living apart). Counselors approached the families to assess their interest and obtained permission to be contacted by the research team. Research staff then provided full information and completed informed consent processes. Up to two caregivers and one adolescent were included per family in assessments, though additional family members were permitted to participate in the treatment sessions. Caregivers were defined as any adult providing care for the child, and if the family had more than one eligible adolescent, families identified one with the most significant concerns likely to be targeted in treatment. During recruitment and baseline assessments, we screened for immediate danger to any individual, in particular related to violence against children or intimate partner violence (IPV). We continually monitored for these concerns throughout treatment, though no families were excluded or withdrew for these reasons.

Of the 18 referred families, 10 completed treatment. Of the remaining, 3 did not consent, 2 consented but did not begin, and 3 began but did not complete treatment. Reasons were primarily logistical, including moving from the community or realizing the child was out of the eligible age range. Among families who completed, 6 out of 10 adolescents were female, and the mean age was 14 years with a range of 12 to 17. The average caregiver age was 39 years, with a range of 26 to 61, and all except one caregiver were biological parents of the adolescents. The majority had primary-level education, with three caregivers also having completed some secondary school (high school). Eight families had two caregivers living in the home, and two were single mothers. Most caregivers had some type of work outside of the home, even if casual labor. Family characteristics are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of treated families

| ID | Members | Target child |

Female caregiver |

Male caregiver |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Gender | Age | Working | Educationa | Relation to child | Age | Working | Education | Relation to child | Marital status | ||

| 1 | 4 | 16 | Female | 40 | Yes | Standard 5 | Mother, biological | - | - | - | - | Not in a union |

| 2 | 6 | 13 | Male | 33 | Yes | Standard 3 | Mother, biological | 42 | Yes | Standard 5 | Father, biological | Married, living together |

| 3 | 7 | 13 | Female | 33 | No | Standard 5 | Mother, biological | 36 | No | None | Father, biological | Married, living together |

| 4 | 9 | 12 | Male | 61 | No | Form 3 | Mother, biological | 47 | Yes | Form 4 | Father, biological | Married, living together |

| 5 | 9 | 16 | Female | 31 | Yes | Standard 4 | Mother, biological | - | - | - | - | Married, living separate |

| 6 | 5 | 13 | Male | 35 | Yes | Standard 7 | Mother, biological | 45 | Yes | Standard 7 | Father, biological | Married, living together |

| 7 | 8 | 17 | Male | 35 | No | Standard 7 | Mother, biological | 43 | Yes | Form 4 | Father, biological | Married, living together |

| 8 | 5 | 12 | Female | 39 | Yes | Standard 8 | Mother, biological | 43 | Yes | Standard 8 | Father, biological | Married, living separate |

| 9 | 7 | 14 | Female | 30 | Yes | Standard 8 | Mother, biological | 38 | Yes | Standard 5 | Father, stepfather | Married, living together |

| 10 | 10 | 15 | Female | 26 | Yes | Standard 3 | Mother, biological | - | - | - | - | Not in a union |

In the Kenyan education system. Standard refers to grade levels in primary school and Form refers to grade levels in secondary school

Intervention

Tuko Pamoja (TP), “We are together” in Kiswahili, is a family therapy intervention that aims to create a positive family environment supportive of positive child and adult outcomes. Our team, including psychologists from Kenya and the United States, developed TP after conducting a qualitative study that guided the selection of evidence-based strategies. The qualitative data allowed us to identify salient indicators of dysfunction that were associated with child mental health and family violence, which became the core targets of the intervention: conflict about roles and responsibilities, favoritism/discrimination, harsh discipline, distance and mistrust in parent–child and marital relationships, and avoidant or negative communication. We describe the development process and content details in Puffer et al. (2019).

TP draws on evidence-based strategies from solution-focused and systems-based family therapies, as these most clearly aligned with intervention targets and were expected to be amenable to integration with the current informal counseling practices (Kerr 1981; Minuchin and Nichols 1998). Structured solution-focused strategies in particular were a natural fit with the existing informal practices of providing problem-specific advice; TP kept the focus on action plans, while shifting from advice-giving to guiding a client-led process. Systems approaches also fit given the importance of discussing roles, including gender roles, in creating relationship interaction patterns. For components on individual mental health, simplified behavioral coping and problem-solving strategies are emphasized (Dobson and Dozois 2019), as similar strategies have been used in Kenya with promising results (Dawson et al. 2015). Sessions are typically completed in homes, involving different constellations of family members as needed.

Table 2 outlines the content and structure of TP. The intervention is manualized and organized by modules, with families receiving only the modules they need. Core modules address problems in different family relationships: couples, parent–child, and overall family cohesion/organization. These modules share 10 core steps that distill clinical strategies. Initial steps focus on assessment of interaction patterns, and the middle stage emphasizes communication skills, sharing of cognitions and emotions, and reflection on past solutions. Final steps include envisioning improvement through the hallmark “miracle question” from solution-focused therapy, goal-setting, action planning, homework, and tracking progress. Steps are initially completed sequentially, with flexibility to return to earlier steps as needed. For most steps, the counselor poses overarching prompts with probes, with a major goal of facilitating communication between members to generate their own solutions. There are small didactic components but minimal direct advice-giving. In addition to the core family modules, there are two briefer ones for individual distress: one for adolescents and one for caregivers. An additional brief module is also included related to communication about sex, HIV, and related behaviors given concerns about HIV and early pregnancy in this context.

Table 2.

Tuko Pamoja Intervention Outline

| Module | Evidence-based strategies |

|---|---|

| Introduction | Family engagement Psychoeducation (counseling purpose; systems understanding of family) Systems-focused problem assessment |

| A: Building stronger parent-child relationships | 10 Core Steps* (solution-based and systems-focused family therapies) |

| A1: General relationship concerns | Parenting skills training |

| A2: Behavioral problems | Includes child-only, parent-only, and joint sessions |

| B: Building a stronger marriage | 10 Core Steps* (solution-based and systems-focused family therapies) |

| C: Building an organized and | 10 Core Steps* (solution-based and systems-focused family |

| united family | therapies) |

| D: Coping with caregiver distress | Brief cognitive behavioral coping skills training Individual caregiver sessions |

| E: Coping with child/adolescent distress | Brief cognitive behavioral coping skills training Includes individual child sessions and a parent session |

| F: Sexual risk behavior (optional session) | Parent-child communication skills practice related to risk behavior; incorporates knowledge-based questions about HIV transmission and pregnancy risk and brief discussion of positive sexuality |

| Transition sessions (after completion of each module) | Solution-focused progress tracking Systems-based assessment of remaining needs Choice of next module or graduation |

| Graduation session | Solution-focused progress acknowledgement and planning (includes identifying ongoing sources of community/family support) |

| *10 Core Steps (drawn largely from solution-based and systems-focused family therapies) | |

| 1. Get the story (understand the family system) | |

| 2. Scaling question (assess severity of the problem) | |

| 3. Positive communication skills (didactic, modeling, and practice components) | |

| 4. Build empathy (share thoughts and feelings) | |

| 5. Identify previous solutions | |

| 6. Identify exceptions (times/circumstances when problems do not occur) | |

| 7. Miracle question (envision life if problems were solved; describe associated behavioral changes) | |

| 8. Set specific relationship goal | |

| 9. Develop action plan | |

| 10. Track progress and continue change | |

The family, counselor, and supervisors decide collaboratively which modules are delivered. After each module, they make a decision about which module, if any, is needed next based on the remaining concerns. In this study, most families completed two modules, most commonly including the marriage and parent–child relationship modules. While the manual is structured, activities are not time-limited, and there are not strict session length expectations in efforts to mirror the local norm of flexible scheduling. Process data from this study showed that, on average, families received 15 sessions lasting a mean of 39 min each, totaling an average of approximately 9 treatment hours. The time period over which the intervention was delivered varied greatly (range: 15–48 weeks), reflecting that sessions often did not happen weekly.

Procedures

Training and supervision

Counselors received 60 h of training from the lead researchers, including clinical psychologists from the United States and Kenya (EP, DA), as well as a doctoral student (EF). Training focused on both general clinical skills and treatment-specific skills and content, with a focus on role plays and peer feedback. Trainers observed counselors in role plays to assess their ability to deliver the content and their general clinical competency to ensure that the counselor was prepared to begin working with a family. After 6 months, the manual was revised to improve clarity and re-order some steps based on first cases. A 40 h refresher training was then delivered. This approach shares many commonalities with lay provider training methods used across task shifting interventions in LMICs (Kakuma et al. 2011; Singla et al. 2014). While this is relatively brief training, evidence suggests this length may be sufficient when focused on limited, structured content streamlined for lay providers and coupled with ongoing supervision (Joshi et al. 2014).

We followed a tiered supervision model in which local supervisors are trained to supervise lay counselors, and local supervisors receive supervision or consultation from more extensively-trained mental health professionals (Murray et al. 2011). For this study, local supervisors were four university students in their third year of studying medical psychology—an undergraduate major that includes clinical skills training and practicum rotations. They therefore received practicum training hours for supervision, allowing us to contribute to their clinical training while providing low-cost supervision. Supervisors received an initial 40 h training and participated in counselor training. They supervised counselors one-on-one after each session, in person or via phone, and received weekly supervision and consultation from doctoral-level psychologists—one in Kenya and one in the US. Following feedback from psychologists on a given session, the student supervisor contacted the counselors to provide guidance for the following session. As these were the counselors’ first cases, supervision served as an extension of the training process.

Data collection

Family participants completed pre-post surveys and a post-intervention qualitative interview, both completed verbally with Kenyan research assistants. A subsample of five families also completed a pre-post direct observational measure of family functioning. Therapy sessions were audio-recorded and transcribed directly into English by Kenyan research assistants fluent in Kiswahili and English. During research assessments and therapy sessions, participants were compensated with small snacks or a small food item for the household (e.g., sugar).

Outcome Measurement: Survey Measures

Primary outcomes were family functioning and mental health. Secondary outcomes included harsh discipline, couples’ violence and harshness, alcohol use, and alcohol-related conflict. Table A1 (online) summarizes instrument information and internal consistency, with all alpha values above 0.7. We adapted or developed scales for this setting based on the qualitative findings that also guided intervention development, as results identified specific positive and negative indicators of both family functioning and mental health. Following this qualitative work, we reviewed existing measurement tools related to our outcomes of interest. With few measures rigorously validated in Kenya, we adapted existing measures when they matched locally-salient indicators and developed new items when existing measures were not consistent with locally-salient indicators. For all measures, we followed transcultural translation procedures to ensure understandability and relevance (van Ommeren et al. 1999). This included cognitive interviewing of each item with multiple adolescents and caregivers from the target population, as well as review by Kenyan mental health experts. Across scale measures, we averaged responses to create composites.

Family functioning was assessed among children and caregivers with nine items that asked about both positive indicators (“sitting and laughing together”) and negative indicators (“quarreling”) of family functioning. Participants responded on a 10-point scale using a visual cue of a ladder. The anchor for Step 1 was “a little,” and the anchor for Step 10 was “a lot.” Positively worded items were reverse coded and responses were averaged to create a composite score that ranged from 1 to 10, with higher scores reflecting worse functioning. Seven of the 9 items make up a longer 30-item instrument developed after this study by the authors and validated in Kenya with a clinical gold standard (Puffer et al. 2018). We extrapolated from the cut-off scores established for the 30-item instrument to suggest a rough guide to better anchor the results of the current study. Results suggest that equivalent cutoff scores for this smaller group of items would be approximately 3/10 for both caregivers and children, with scores above these likely indicative of significant family distress.

Couples’ relationship quality was assessed with 11 items, including 7 from the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Spanier 1976) and 4 locally-developed items. Participants responded on a 6-point scale from “none of the time” (0) to “all of the time” (5).

Child mental health was assessed by child- and caregiver-report using the 19-item ASEBA Brief Problem Monitor (BPM) that assesses children’s functioning and responses to intervention (Achenbach et al. 2011). Participants responded on a 3-point scale: “not true” (0); “somewhat or sometimes true” (1); “very true or often true” (2). Both children and caregivers reported on the child’s behavior, resulting in composite scores for each reporter. The corresponding longer ASEBA scales have been used quite extensively in Kenya, showing good psychometric properties (Magai et al. 2018).

Caregiver mental health was assessed with 3 items from the General Health Questionnaire (Goldberg 1972). Responses were on a 4-point scale from “never” (0) to “often” (3) (Watson et al. 2020).

Child harsh treatment was assessed through child- and caregiver-report using items from the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (UNICEF 2010) and the Discipline Interview (Lansford et al. 2005). Participants reported frequency of (a) beating with an object and (b) spanking/slapping/hitting in the past 2 months using a 4-point scale from “never” (0) to “many times” (3).

Intimate partner violence (IPV) and harsh marital interactions were assessed with single items administered to both caregivers, asking about the past 2 months. Verbal IPV was assessed with a single item from the Conflict Tactics Scale asking whether partners have “insulted, shouted, or yelled” at one another (Straus and Douglas 2004). Physical IPV was assessed with one locally-developed item about “physically hurting” one’s partner. General harsh marital interactions were also assessed with a locally-developed item about being “very harsh” towards one’s partner “when you disagree.” For all, caregivers responded on a 5-point scale from “never” (0) to “more than 8 times” (4).

Alcohol use and alcohol-related conflict were assessed with a series of single items assessing behaviors over the past 2 months on a 5-point scale from “never” (0) to “4 or more times a week” (4). Frequency of drinking was assessed with one item from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test asking how often one has “had a drink containing alcohol” (Babor et al. 2001). Frequency of “coming home drunk” was assessed with a locally-developed item. Caregivers reported about their own behavior and that of their spouse. Caregivers and adolescents then reported on a series of items assessing frequency of conflict when a caregiver was drunk; these items followed this structure: “In the past 2 months, how often have you quarreled with your [spouse, children] when [you/your spouse/your parent] was drunk?”

Observational measure

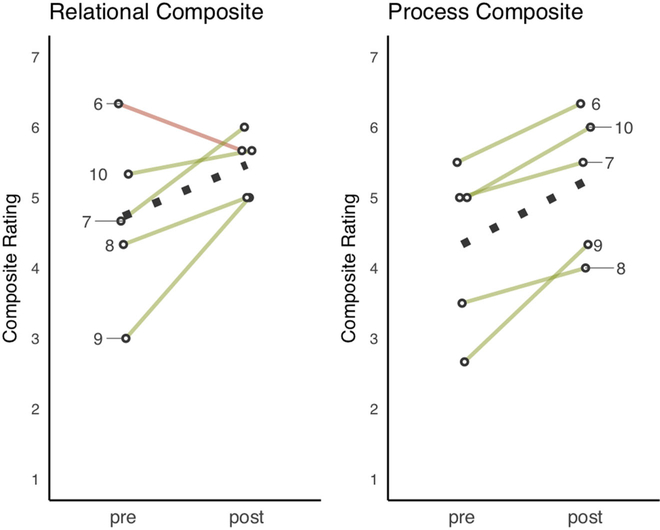

Five families participated in three, 10 min structured activities that were administered by Kenyan research assistants in family homes; videotaped; and rated using a structured coding system. We adapted this tool from the Family Problem Solving Code (Forbes et al. 2001). For a full description of our adapted measure, see Giusto et al. (2019). Activities were administered pre- and post-intervention and included: a teamwork activity, a couples’ discussion, and a family discussion. For each of the activities, a 7-point scale was used to rate multiple domains: positive behavior (0 = Virtually None; 7 = A Lot), negative behavior (same scale), relationship quality (1 = Not at All Close; 7 = Exceptionally Close), and quality of problem-solving/planning process (1 = Extremely Poor; 7 = Extremely Good). Two composite scores included: (1) Quality of Interactions-Relational: average of Positive Behavior, Negative Behavior (reverse scored), and Relationship Quality ratings across activities and (2) Quality of Interactions-Process: the average of the problem-solving and planning processes rating across activities. Raters were trained, reaching 80% inter-rater agreement before completing coding training. Two raters then rated all interactions independently and discussed discrepancies to reach full agreement on all ratings.

Post-intervention qualitative interview

Individual in-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted with each participant after treatment about experiences of therapy and perceptions of changes. Interviews were conducted in Kiswahili by a research assistant, audio-recorded, and transcribed directly into English. The interview included broad, open-ended questions followed by more specific probes. The primary open-ended question on perceived changes was: “How did your family change as a result of the counseling? Tell me what your family was like before and what it is like now.” Probes focused on family problems, including conflict, violence, and positive interactions; changes within members; possible negative changes; and expectations for sustainment of changes.

Process Measurement

Process evaluation measures included indicators of fidelity and clinical competencies, and we provide a detailed report on feasibility and acceptability elsewhere (Puffer et al. 2019). A fidelity assessment tool was developed for TP and completed by a Kenyan research assistant based on session recordings and transcripts. The tool first assessed completion (yes/no) of the steps in the manual (within a particular module) and, for completed steps, assessed the quality with which each step was completed ranging from poor (1) to excellent (5). This yields: (1) percentage of steps completed and (2) mean quality score per session. Two types of clinical competency were measured. First, counselors’ use of general clinical skills was measured using seven items adapted for family treatment from the ENhancing Common Therapeutic Factors (ENACT) scale developed for lay counselors in LMICs (Kohrt et al. 2015). Example items include verbal communication skills and rapport building. Second, competencies relevant specifically to TP were measured using a 7-item measure developed for TP using the same structure as ENACT. This included items such as “focus on the family system.” All items were rated from poor (1) to excellent (4). Both fidelity and competency measures were rated for four sessions per family representing the early, middle, and later stages of treatment. Two raters completed the ratings using transcripts, establishing 80% agreement for all items during training.

Analysis

We estimated average treatment effects based on pre-post survey data by fitting linear mixed models with a fixed effect for post-treatment observations and a random effect for person and, in the case of caregiver-reported outcomes, nested random effects for caregivers within households. For observational assessment data, we plotted family-level ratings of Overall Interaction Quality and Problem-solving. Lastly, we calculated descriptive statistics to summarize process evaluation findings.

We conducted a thematic content analysis of post-treatment interview transcripts (Braun and Clarke 2006) and included both deductive and inductive codes. Deductive codes were drawn from literature on constructs of family functioning consistent with previous qualitative data, including those presented in the General Assessment of Relational Functioning (Guttman et al. 1996). These included parent codes, such as “Couples’ Functioning,” with specific child codes, such as “Conflict Resolution.” Similar sets of codes were developed for parent–child and family-wide relationships. Inductive themes were identified through reading of interview transcripts by multiple team members, continuing until no new themes were identified as additional transcripts were reviewed. Examples of inductive codes included those related to culture and context: “Gender Influence” and “Religion.” Themes were combined into a codebook, with code definitions developed and reviewed collaboratively by four members of the research team. Two team members independently applied the codebook to three transcripts until 80% agreement was reached, with all discrepancies discussed to reach consensus and changes made to the codebook to improve reliability. Transcripts were then divided between the two and coded using NVivo version 11.0 software. Thematic summaries were developed for each code to synthesize main themes, and summaries were reviewed and discussed with the first author.

Results

Treatment Effects

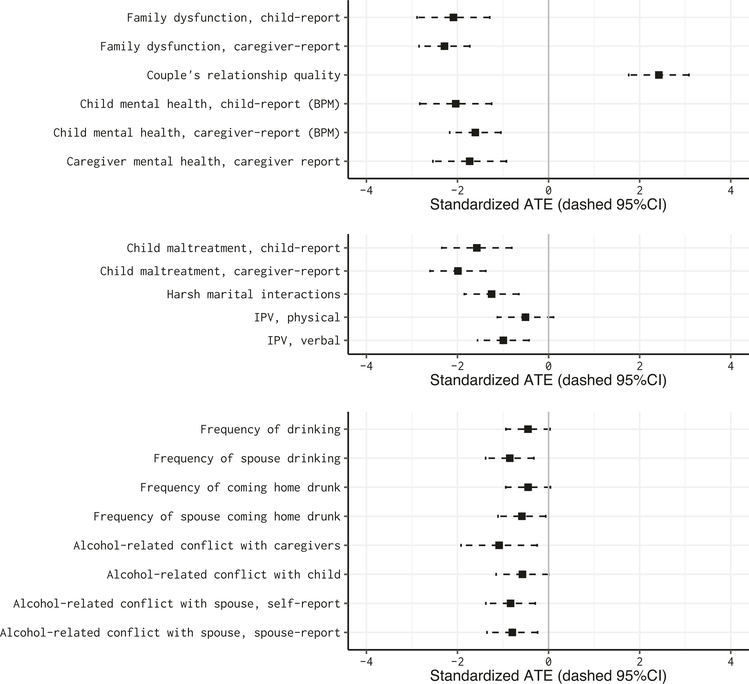

Figure 1 displays the average treatment effects (standardized) for the primary and secondary outcomes. See Table 3 for numerical summaries and test statistics. All point estimates are in the expected direction, and most 95% confidence intervals exclude zero.

Fig. 1.

Standardized average treatment effect estimates. Black squares symbolize effects in the hypothesized direction

Table 3.

Average treatment effects: primary and secondary outcomes

| Outcome | Possible | Pre | Post | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Possible Range | Higher | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | B | Glass’s Δ (95% Cl) | t(df) | P | H/N | |

| Primary outcomes | ||||||||||

| Family dysfunction, child-report | 9 | 1–10 | Neg | 5.8 (1.7) | 2.3 (0.5) | −3.51 | −2.09 (−2.9, −1.3) | 6.0 (8) | <0.001 | 9/9 |

| Family dysfunction, caregiver-report | 9 | 1–10 | Neg | 5.4 (1.5) | 2.1 (0.6) | −3.34 | −2.28 (−2.8, −1.7) | 8.8 (14) | <0.001 | 10/15 |

| Couples’ relationship quality | 11 | 0–5 | Pos | 2.1 (1.1) | 4.7 (0.4) | 2.58 | 2.42 (1.8, 3.1) | 8.1 (11) | <0.001 | 8/12 |

| Child mental health, child-report (BPM) | 19 | 0–2 | Neg | 0.6 (0.3) | 0.1 (0.1) | −0.54 | −2.04 (−2.8, −1.3) | −6.1 (7) | <0.001 | 8/8 |

| Child mental health, caregiver-report (BPM) | 18 | 0–2 | Neg | 0.7 (0.4) | 0.0 (0.0) | −0.65 | −1.61 (−2.2, −1.0) | −6.2 (12) | <0.001 | 9/13 |

| Caregiver mental, caregiver-report | 3 | 0–3 | Neg | 1.5 (0.7) | 0.3 (0.5) | −1.27 | −1.73 (−2.5, −0.9) | −4.8 (10) | <0.001 | 9/11 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||||||

| Child maltreatment, child-report | 2 | 0–3 | Neg | 1.6 (0.9) | 0.1 (0.3) | −1.44 | −1.58 (−2.3, −0.8) | −4.7 (8) | 0.001 | 9/9 |

| Child maltreatment, caregiver-report | 2 | 0–3 | Neg | 1.6 (0.7) | 0.1 (0.5) | −1.47 | −1.99 (−2.6, −1.4) | −7.0 (14) | <0.001 | 10/15 |

| Flarsh marital interactions | 1 | 0–4 | Neg | 2.0 (1.4) | 0.2 (0.6) | −1.77 | −1.25 (−1.9, −0.7) | −4.5 (12) | <0.001 | 8/13 |

| IPV, physical | 1 | 0–4 | Neg | 0.8 (1.4) | 0.1 (0.3) | −0.69 | −0.51 (−1.1, 0.1) | −1.8 (12) | 0.098 | 8/13 |

| IPV, verbal | 1 | 0–4 | Neg | 1.7 (1.5) | 0.2 (0.4) | −1.54 | −0.99 (−1.6, −0.4) | −3.8 (12) | 0.002 | 8/13 |

| Frequency of drinking | 1 | 0–4 | Neg | 0.8 (1.5) | 0.1 (0.4) | −0.67 | −0.45 (−0.9, 0.0) | −2.0 (14) | 0.065 | 10/15 |

| Frequency of spouse drinking | 1 | 0–4 | Neg | 1.6 (1.6) | 0.2 (0.5) | −1.33 | −0.85 (−1.4, −0.3) | −3.5 (11) | 0.005 | 7/12 |

| Frequency of coming home drunk | 1 | 0–4 | Neg | 0.7 (1.3) | 0.1 (0.4) | −0.60 | −0.45 (−0.9, 0.0) | −2.0 (14) | 0.070 | 10/15 |

| Frequency of spouse coming home drunk | 1 | 0–4 | Neg | 1.0 (1.3) | 0.2 (0.5) | −0.75 | −0.59 (−1.1, −0.1) | −2.5 (11) | 0.032 | 7/12 |

| Alcohol-related conflict with caregivers | 1 | 0–4 | Neg | 1.9 (1.7) | 0.0 (0.0) | −1.88 | −1.09 (−1.9, −0.2) | −3.1 (7) | 0.018 | 8/8 |

| Alcohol-related conflict with child | 1 | 0–4 | Neg | 0.8 (1.4) | 0.0 (0.0) | −0.79 | −0.57 (−1.2, 0.0) | −2.1 (13) | 0.051 | 9/14 |

| Alcohol-related conflict with spouse, self- report | 1 | 0–4 | Neg | 1.3 (1.5) | 0.1 (0.3) | −1.25 | −0.83 (−1.4, −0.3) | −3.4(11) | 0.006 | 8/12 |

| Alcohol-related conflict with spouse, spouse- report | 1 | 0–4 | Neg | 1.1 (1.3) | 0.1 (0.3) | −1.00 | −0.80 (−1.4, −0.2) | −3.1 (12) | 0.009 | 8/13 |

For child-reported outcomes, H = N, as there was only one target child per household. For caregiver-reported outcomes, FI = number of target children and N reflects multiple caregiver reporters per household

H households, N observations

Across the primary outcomes, standardized point estimates of the effect sizes ranged from 0.6 to 2.4 standard deviations, with the largest effect observed on couples’ relationship quality. The average quality increased from a score of 2.1 (out of 5) at baseline to 4.7 after the intervention. This doubling in quality scores put the post-treatment average near the top end of the scale. We also observed large absolute decreases in reported family dysfunction. According to both child- and caregiver-report, the average family entered the study above suggested numerical cutoffs indicative of family dysfunction. After the intervention, the average family reported substantially lower scores that were below the cutoffs. We observed a similar trend for child and caregiver mental health. The difference is that, on average, child mental health problems were at a sub-clinical level at baseline according to both child- and caregiver-report (M = 0.6 and M = 0.7, respectively). Still, following treatment, both child- and caregiver-reported average scores fell by slightly more than half of a standard deviation to near zero, suggesting that on average both reporters believed that children had no concerns post-treatment. For caregiver mental health, the mean baseline score was also relatively low (1.5/3), with post-treatment scores close to zero, reflecting almost no concerns.

For violence-related outcomes, all estimates were also in the expected direction. Both children and, to a larger extent, caregivers, reported reductions in child harsh treatment. IPV, both verbal and physical, as well as general harsh interactions, also decreased, though to a lesser extent. Alcohol-related outcomes also reflect change in the expected direction, including those related to actual drinking behavior and the impacts of drinking on family interactions. Across these secondary outcomes, standardized point estimates of the effect sizes ranged from 0.51 to 1.99 standard deviations.

The improvements in family relationships observed in survey results are supported by observational data. Plots of pre-post composite ratings showed positive change trajectories for all families on the process composite and for all except one on the relational composite. These reflected increases in positive interactions and decreases in negative interactions from baseline. (Notably, the family that showed a decrease on the relational composite had the highest score at baseline, and the post-test score was still among the highest). Figure 2 shows plots with results by family.

Fig. 2.

Pre-post composite ratings of family relationship quality for the subsample of families who participated in the family observation activities. Family identification labeled. Dotted lines represent pre-post averages

Qualitative Descriptions of Change: Post-intervention interview

Family functioning

During the interview, families described that they had experienced persistently negative interactions in their homes before treatment, characterized by disagreements, lack of understanding and respect, and “quarrels.” Many reported behaviors consistent with verbal and/or physical violence. Several encapsulated their turbulent emotional climate by describing that family members “go their own way” (Kiswahili: kuenda kivyao) to avoid the quarreling. This took the form of children running away, one parent leaving the home, or members avoiding one another within the home. One child described the quarreling and distance in the household, saying, “[My father] used to drink alcohol… He used to come in the evening to quarrel with mother. There were just disagreements in the house. Nobody was staying there. Everyone went on their own just to avoid the noise.”

All families reported an increase in time spent together following the intervention, which they described as resulting in improved communication. In contrast to “going their own way,” families described “sitting together” (Kiswahili: kukaa pamoja), a phrase used to reflect improved communication, understanding, and respect, in addition to more physical time spent together. Families associated sitting together with fairer task distribution, better emotional climate and closeness, improved problem-solving, decreased violence, and overall more effective and predictable organization within the home environment. Several families specifically reported this leading to fathers spending less money on alcohol and more on family needs. One father recognized the very practical implications of communication and organization, describing: “When we do some work, at least we have plans on what [to do]… I go there, and the mother also goes to look for money, and we meet in the evening, and we look at the money we have brought and plan on it. I give her the ability to plan like this for school and this for food and so on.” Here, it is also evident how roles and responsibilities became clearer within families, at times resulting in gradually increased decision-making power for women.

Couples’ relationships

All couples reported that lack of communication was the primary reason for marital problems before therapy. In most cases, financial issues were the main source of conflict, including IPV in some cases, with many attributing these to the father’s alcohol use. During the post-treatment interview, all described better communication, and about half specifically mentioned better conflict resolution. Several attributed improvements to enhanced communication skills related to “listening” and “respect”—skills explicitly taught in TP. One mother described the new system she and her husband developed to discuss earnings and use of their wages: “I am a tailor and whenever I get what I get, I bring it home, and when I arrive home, we communicate through phone…The other is saying, ‘There is no flour today; bring vegetables and flour. ‘ We started communicating this way, and I can see that there is no disagreement now. When he says that there is nothing at all, I won’t be angry at him.” One child reported noticing a difference in his parents’ interactions, recalling, “[My] parents were fighting and quarreling, but now the problem has ended. Now they talk to each other and solve their problems; it’s not like before.”

Parent–child relationships

When recalling their pre-treatment interactions, couples rarely described working together to fulfill parenting responsibilities. Rather, several mothers reported being solely responsible for children because the children feared the father or because he was often drunk or away. Additionally, several reported pre-therapy problems with father-child relationships, including fathers failing to communicate well or beating children excessively. A mother described the distance between her children and their father pre-therapy: “Most of the time he was drunk and so he rarely met with the children; he rarely talked deeply with the children; the children did not talk to him about their problems.” Following therapy, all reported improved father-child relationships, including spending more time together, being able to “talk well,” fathers recognizing children’s needs, and less frequent beating. As a result, children reported feeling more comfortable sharing problems with their father. A father gave an example to illustrate their increased comfort: “Even today as we were coming, they were borrowing [from] me 5 shillings.” He contrasted this with, “In the past, they used to see me as wild in the house; I was a lion.” The fact that the children felt comfortable enough to request money was meaningful to him, as requesting money or goods from fathers was often a trigger for harsh treatment.

Mothers and children reported having closer relationships than fathers and children before the intervention. However, they described that most mother-child communication was limited to talking about material needs. Some reported that children acted out because they could not express emotions or relay experiences to their mothers. Post-therapy, about half of mothers reported more understanding of their child’s emotions and behaviors, leading to less harsh disciplining. A mother described, “He [counselor] educated me on how to handle my daughter…that it is better I sit and talk to her [instead of caning], telling her which is right and wrong.”

Adolescent mental health

Most families reported that family conflict affected adolescents in significant ways. Adolescents reported that they previously tried to avoid quarrels, which sometimes led to risky behavior patterns, such as spending nights outside the home. One youth remembered his reactions pre-treatment: “Father and mother were fighting at home, so [I would go] at a place with my friends. We were just hanging around town.” Children also described parents being unable to pay school fees and that requesting fees led to quarrels or beating. A mother recalled the emotional distress of her daughter related to lack of fees and being sent home from school, recounting: “She would come home crying. There is a time she was stressed and wanted to commit suicide.” Post-intervention, several families reported talking with children, making conscious efforts to problem-solve to meet their needs, rather than becoming angry. Most also reported positive changes in adolescent behavior. A few reported that pre-therapy, children were not obeying them in terms of doing chores, spending money as instructed, or returning home as asked. Post-therapy, most described that improved communication led to clearer expectations, resulting in changes, such as adolescents helping parents at home and arriving home on time.

Caregiver mental health

Most caregivers recalled stress and associated thoughts and behaviors before counseling. Many fathers reported that they had experienced thoughts of leaving the family, and multiple mothers reported the desire to kill herself due to poor conditions within the family. One father described, “I had the idea of leaving but not to harm myself; but my partner [wife]…had the thoughts. She was saying that she would poison everyone and stop living this life.” One mother also reported experiencing physical symptoms, including fainting, due to “pressure.” Almost all reported lower stress after the intervention, and no one reported persistence of suicidal ideation. Some described engaging in coping skills, often related to recognizing they are equipped to handle problems and there is hope; at times, they described stress relief from improved family relations alongside finding strength in their faith. One mother said, “I can see that I have changed, even when I see something, I don’t stress myself over it. I have persevered in all that, and I call my God. I thought of an idea in my heart and told myself that ‘in everything, you persevere.’”

Process Evaluation

Across rated sessions, counselors achieved a mean of 79% fidelity and a mean of 3.2 (out of 5) for ratings on quality, corresponding to a rating of “fair.” Counselors achieved a mean of 20.7 (out of 28) for general clinical competencies and a mean of 20.6 (out of 28) for TP-specific competencies. These reflect “moderate” skills use. Overall, results suggest adequate fidelity and skills use for the delivery of TP, consistent with the definition for adequate quality used in previous studies in LMICs—whether delivery is adequate for reaching the goals of a treatment (Singla et al. 2014). More detail on fidelity and competency results are reported elsewhere (Puffer et al. 2019).

Discussion

Participants in a family therapy intervention (Tuko Pamoja: “We are together”) exhibited positive, pre-post clinical change across several domains, including family functioning, couples’ relationship quality, and mental health of both adolescents and caregivers. In addition, participants reported reductions in harsh behaviors related to treatment of children and IPV, as well as improvements in alcohol-related problems. This study builds on the evidence supporting the role of family-based interventions in global mental health (Knerr et al. 2013; Mejia et al. 2012) and fills two gaps in the literature: (a) an initial test of an approach for helping higherneed families, (b) application of a broader range of family therapy strategies that focus beyond the parent–child dyad, and (c) the integration of individual-level mental health strategies alongside the primary family components.

Taken together, findings are promising and provide a foundation for planning future evaluations of Tuko Pamoja. We are cautious in interpretation of results, however, given the pre-post design and small convenience sample of only 10 families. To maximize learning from this pilot, we included multiple reporters per family and triangulated quantitative, qualitative, and observational data. Findings showed that all primary and secondary outcomes moved in the expected direction across both child- and caregiver-report. Our results also followed an expected pattern in that effects were larger on outcomes like family functioning, which are likely more amenable to changing over the short-term than individual mental health. Third, the quantitative findings were consistent with the results of our qualitative inquiry and family observations.

A particularly informative pattern was that we observed positive pre-post changes at the individual, dyadic, and whole family levels. One of our central questions was whether TP could intervene at multiple levels while addressing varying types of problems presented by the target population. While there is a clear need to target multiple levels simultaneously—especially when addressing family risk factors for mental health and violence—there are potential challenges when combining strategies and incorporating a wide range of goals. Results suggest, however, that the approach was feasible and that streamlining clinical strategies into steps and maximizing commonalities across modules may be a useful method for developing an intervention with numerous goals for use by lay counselors. This approach is analogous in some ways to other transdiagnostic approaches used in individual treatment that emphasize the efficiency and effectiveness of using core clinical strategies matched to specific needs (Chorpita et al. 2005). These include the common elements treatment approach that has been applied successfully in other LMICs (Murray et al. 2014), and results of the current study suggest that many of these same principles are applicable for addressing problems in the overall family system.

One advantage of an intervention that incorporates a components-based approach including solution- and systems-based family therapy strategies is that families lead the process of defining goals and action plans. This allows for the natural integration of context- and culture-specific material as it arises. In this context, financial constraints and alcohol use emerged as two very common topics central to problems in family relationships and mental health. The TP steps allowed counselors to coach families through problem-solving and skills development applied to these challenges even though the intervention does not explicitly include alcohol- or finance-related content. In many cases, this seemed effective, as families recognized interaction patterns blocking their ability to problem-solve effectively to cope with these circumstances. That said, treatment was more difficult for families impacted by more severe patterns of drinking and poverty, which raised the question of when other adjunctive interventions may be valuable for some families; for instance, intensive treatment for substance use or immediate financial assistance may be beneficial alongside TP if these problems become barriers preventing families from engaging in the family therapy. Other culture- and context-influenced factors also arose during treatment, including problems in extended family relationships, concern related to HIV risk, issues of favoritism and discrimination affecting orphans, and issues related to oftenrigid gender roles. These were predicted based on formative qualitative work, and results suggest that the flexibility of TP allowed counselors to address these issues directly within the steps in ways that were tailored to specific family dynamics.

Process evaluation results were also promising, especially given that these were counselors’ first cases. It proved feasible to identify lay counselors who were already serving as informal counselors in their communities and to train them in family therapy delivery. While lay counselors have been trained successfully in a variety of therapeutic strategies in LMICs (Joshi et al. 2014; Singla et al. 2014), our results are somewhat unique in that (a) the lay counselors were not community health workers or recruited within a health system or non-governmental organization and (b) TP, while manualized, requires lay counselors to implement strategies more flexibly than many more prescriptive interventions. As an example, counselors must often facilitate challenging interactions between family members while they are attempting to complete the goal-setting and action-planning steps; they are expected to balance following the family’ s lead with accomplishing the specified goals of each step. Many counselors’ ability to develop the clinical awareness needed to carry out these strategies was encouraging.

Limitations

As described above, central design limitations of this initial pilot trial included a small convenience sample and the pre-post design, as a number of factors could contribute to the observed changes. In addition, this study has limitations related to measurement and data collection. First, while we used qualitative data to guide measurement decisions and conducted extensive item testing, we do not have standardized assessment tools that have been validated in this context for many of the outcomes. Second, we were only able to collect observational data from half of the sample, and the fact that observational raters were not blinded to time point (pre vs. post) may have led to unintentional bias. Third, the intent-to-treat analysis was not possible because the four families who did not complete treatment were not available for post-assessments; this may have biased results if these families were less likely to respond to the intervention. Lastly, the time between completion of the intervention and endline data collection was not uniform.

Future Directions

To build on these preliminary findings, future research is essential for testing efficacy using experimental research designs that can test causality. Larger studies will also allow for examining effects by family characteristics, such as specific presenting problems and family structure. To accomplish this, it may be useful to conduct studies with stricter inclusion criteria for co-occurring problems (e.g., mental health symptoms) to examine effects of TP for subpopulations of families and individuals, including those with mental health disorders. In the current study, broadly-defined family dysfunction was the one unifying characteristic bringing families into the intervention, meaning that pre-treatment problems on the other target outcomes (e.g., mental health, IPV, alcohol use) varied widely. For many outcomes, this led to relatively low average pre-treatment scores for the group overall; this was the case for child mental health despite counselors attempting to prioritize families with adolescents with suspected concerns. Alongside examining specific presenting problems, it will be important to include adequate numbers of families with varying structures, considering factors such as number of members and biological vs. non-biological relationships. Previous research is clear that there are unique challenges for stepfamilies (Papernow 2013), and we were unable to explore this with only one non-biological child in the study.

Additional directions for future research include: (1) measuring unanticipated outcomes that emerged qualitatively, including potential economic benefits, (2) including a broader range of participants in sessions, including younger children, and encouraging the involvement of more family members in sessions and assessments, and (3) examining mechanisms of change to identify strategies most strongly associated with change; sequences of and interactions between changes; and mediators and moderators of change. Lastly, if TP proves effective, future work should examine the potential of combining TP with individual-level treatments or poverty alleviation strategies for which adding a family-based component may boost effects.

Implications for Family Therapy in Low-Resource Contexts: Feasibility and Fit

Results point to at least three core implications for the delivery of family therapy to the most underserved. First, the demonstrated feasibility of training lay providers in true family therapy approaches supports the case that family therapy can be part of the movement to develop scalable task shifting interventions worldwide (Chorpita et al. 2005). Second, results suggest therapeutic strategies grounded in family systems theory and principles of solution-focused family therapy are a good fit within this context (Kerr 1981; Minuchin and Nichols 1998). This is advantageous for dissemination across contexts and cultures because these approaches call for client-driven flexibility in which they explore their own values, goals, and solutions. Cultural adaptation is a core challenge—especially in contexts with complex histories of social oppression and structural inequalities (Hernández et al. 2005; Parra-Cardona et al. 2012). These family therapies not only allow, but require, in situ adaptations, creating a natural adaptation process.

Lastly, family therapy strategies used in this study, and likely others, allow us to tackle some of the most complex and distressing concerns facing hard-to-reach, high-risk populations. Most often, interventions in low-resource contexts have focused on individuals. While most practitioners and researchers acknowledge the relational contributors to symptoms, the clinical strategies in most evidence-based treatments do not explicitly address these. Given the prevalence of family violence that can be exacerbated by poverty and structural stress, family therapy can fill an incredibly important gap as a standalone or adjunctive treatment.

With these implications in mind, next steps for practice in both LMICs and low-resource areas of high-income countries could include training lay providers, or a broader range of professionals who are not mental health specialists, in family therapy to increase access to this treatment modality. This would be an important step forward in expanding the reach of more intensive services to socially vulnerable families facing multiple concurrent stressors that can exacerbate problems in family functioning. In clinicians’ delivery of family therapy, results also suggest that a modular approach may be a way to address a wider range of family problems within one integrated treatment plan, while using time and resources efficiently to focus only on areas of need. For instance, a client with initial concerns related to parenting could transition to a module to address couples’ relationship problems that could arise during the process of parenting skills training. In a modular treatment, such as Tuko Pamoja, these modules are designed to build on one another.

Conclusions

This study provides preliminary evidence for the efficacy of a lay counselor-delivered family therapeutic intervention, Tuko Pamoja, delivered in a setting with scarce mental health resources. Results documented improvements in family relationships and decreased family violence, alongside improved mental health of both children and caregivers. This intervention is unique in its use of family therapy strategies that are less common among family-based interventions implemented in low- and middle-income countries—particularly those delivered using a task shifting approach. Findings highlight the potential of these strategies as viable and promising treatment options for families experiencing high levels of distress complicated by mental health concerns in low-resource settings.

Highlights.

Families who received a family therapy intervention from lay providers in Kenya reported improvements in family functioning and mental health.

Specific family improvements included reduced conflict, harsh discipline, intimate partner violence, and alcohol-related problems.

Both caregivers and children reported improvements, and participants described changes in family interactions during in-depth interviews.

Results are preliminary, but multiple improvements across data sources support conducting future studies on this intervention.

Table A1.

Survey measures: Primary and secondary outcomes

| Outcome | Items | Possible Range | Higher | Alphaa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcomes | ||||

| Family relationship quality, child-report | 9 | 1–10 | pos | 0.78 |

| Family relationship quality, caregiver-report | 9 | 1–10 | pos | 0.82 |

| Couple’s relationship quality | 11 | 0–5 | pos | 0.93 |

| Child mental health, child-report (BPMb) | l9 | 0–2 | neg | 0.71 |

| Child mental health, caregiver-report (BPM) | 18 | 0–2 | neg | 0.91 |

| Caregiver mental health, caregiver report | 3 | 0–3 | neg | 0.91 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| Child maltreatment, child-report | 2 | 0–3 | neg | 0.84 |

| Child maltreatment, caregiver-report | 2 | 0–3 | neg | 0.88 |

| Harsh marital interactions | 1 | 0–4 | neg | |

| IPVc, physical | 1 | 0–4 | neg | |

| IPV, verbal | 1 | 0–4 | neg | |

| Frequency of drinking | 1 | 0–4 | neg | |

| Frequency of spouse drinking | 1 | 0–4 | neg | |

| Frequency of coming home drunk | 1 | 0–4 | neg | |

| Frequency of spouse coming home drunk | 1 | 0–4 | neg | |

| Alcohol-related conflict with caregivers | 1 | 0–4 | neg | |

| Alcohol-related conflict with child | 1 | 0–4 | neg | |

| Alcohol-related conflict with spouse, self-report | 1 | 0–4 | neg | |

| Alcohol-related conflict with spouse, spouse-report | 1 | 0–4 | neg | |

Notes.

Alpha = Chronbach’s alpha

BPM = Brief Problem Monitor

IPV = Intimate

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethical Approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board at Duke University (Protocol C0058) and the Institutional Research and Ethics Committee at Moi University in Eldoret, Kenya, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01816-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Ivanova MY, & Rescorla LA (2011). Manual for the ASEBA brief problem monitor (BPM). Burlington, VT: ASEBA, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, & Monteiro MG (2001). Audit. The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): guidelines for use in primary care. http://amro.who.int/English/DD/PUB/AuditBro-3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Boudreault-Bouchard A-M, Dion J, Hains J, Vandermeerschen J, Laberge L, & Perron M (2013). Impact of parental emotional support and coercive control on adolescents’ self-esteem and psychological distress: Results of a four-year longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescence, 36(4), 695–704. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, & Clarke V (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carr A (2009). The effectiveness of family therapy and systemic interventions for child-focused problems. Journal of Family Therapy, 31(1), 3–45. 10.1111/j.1467-6427.2008.00451.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, & Weisz JR (2005). Modularity in the design and application of therapeutic interventions. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 11(3), 141–156. 10.1016/j.appsy.2005.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson KS, Bryant RA, Harper M, Tay AK, Rahman A, Schafer A, & Mvan Ommeren (2015). Problem management plus (PM+): a WHO transdiagnostic psychological intervention for common mental health problems. World Psychiatry, 14(3), 354–357. 10.1002/wps.20255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson KS & Dozois DJA (Eds.) (2019). Handbook of cognitive-behavioral therapies. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes C, Vuchinich S, & Kneedler B (2001). Assessing families with the family problem solving code. In Kerig PK & Lindahl KM (Eds.), Family observational coding systems: Resources for systemic research (pp. 59–75). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 10.4324/9781410605610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giusto A, Kaiser BN, Ayuku D, & Puffer ES (2019). A direct observational measure of family functioning for a low-resource setting: adaptation and feasibility in a Kenyan sample. Behavior therapy, 50(2), 459–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg DP (1972). The detection of psychiatric illness by questionnaire; a technique for the identification and assessment of non-psychotic psychiatric illness. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guttman HA, Beavers WR, Berman E, CombrinckGraham L, Glick ID, Gottlieb F, Grunebaum H, LandauStanton J, Price AL, Wynne LC, & others (1996). Global assessment of relational functioning scale (GARF). 1. Background and rationale. Family Process, 35(2), 155–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández P, Almeida R, & Vecchio KD-D (2005). Critical consciousness, accountability, and empowerment: key processes for helping families heal. Family Process, 44(1), 105–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi R, Alim M, Kengne AP, Jan S, Maulik PK, Peiris D, & Patel AA (2014). Task shifting for non-communicable disease management in low and middle income countries—a systematic review. PLOS ONE, 9(8), e103754. 10.1371/journal.pone.0103754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakuma R, Minas H, Van Ginneken N, Dal Poz MR, Desiraju K, Morris JE, … & Scheffler RM (2011). Human resources for mental health care: current situation and strategies for action. The Lancet, 378(9803), 1654–1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr ME (1981). Family systems theory and therapy. In Gurman AS & Kniskern DP (Eds.), Family systems theory and therapy (vol. 1). London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Khasakhala LI, Ndetei DM, Mathai M, & Harder V (2013). Major depressive disorder in a Kenyan youth sample: relationship with parenting behavior and parental psychiatric disorders. Annals of General Psychiatry, 12(1), 15 10.1186/1744-859X-12-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieling C, Baker-Henningham H, Belfer M, Conti G, Ertem I, Omigbodun O, Rohde LA, Srinath S, Ulkuer N, & Rahman A (2011). Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. The Lancet, 378(9801), 1515–1525. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60827-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knerr W, Gardner F, & Cluver L (2013). Improving positive parenting skills and reducing harsh and abusive parenting in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Prevention Science, 14(4), 352–363. 10.1007/s11121-012-0314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Jordans MJD, Rai S, Shrestha P, Luitel NP, Ramaiya MK, Singla DR, & Patel V (2015). Therapist competence in global mental health: development of the ENhancing Assessment of Common Therapeutic factors (ENACT) rating scale. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 69, 11–21. 10.1016/j.brat.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Chang L, Dodge KA, Malone PS, Oburu P, Palmérus K, Bacchini D, Pastorelli C, Bombi AS, Zelli A, Tapanya S, Chaudhary N, Deater-Deckard K, Manke B, & Quinn N (2005). Physical Discipline and children’s adjustment: cultural normativeness as a moderator. Child Development, 76(6), 1234–1246. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magai DN, Malik JA, & Koot HM (2018). Emotional and behavioral problems in children and adolescents in central Kenya. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 49(4), 659–671. 10.1007/s10578-018-0783-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvel F, Rowe CL, Colon-Perez L, DiClemente RJ, & Liddle HA (2009). Multidimensional family therapy HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention: an integrative family-based model for drug-involved juvenile offenders. Family Process, 48(1), 69–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejia A, Calam R, & Sanders MR (2012). A review of parenting programs in developing countries: Opportunities and challenges for preventing emotional and behavioral difficulties in children. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 15(2), 163–175. 10.1007/s10567-012-0116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin S, & Nichols MP (1998). Structural family therapy. In Dattilio FM (Ed.), The Guilford family therapy series. Case studies in couple and family therapy: Systemic and cognitive perspectives (p. 108–131). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Dorsey S, Bolton P, Jordans MJ, Rahman A, Bass J, & Verdeli H (2011). Building capacity in mental health interventions in low resource countries: an apprenticeship model for training local providers. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 5, 30 10.1186/1752-4458-5-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Dorsey S, Haroz E, Lee C, Alsiary MM, Haydary A, Weiss WM, & Bolton P (2014). A common elements treatment approach for adult mental health problems in low- and middle-income countries. Using Evidence-Based Cognitive and Behavioral Principles to Improve HIV-Related Psychosocial Interventions, 21(2), 111–123. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Hall BJ, Dorsey S, Ugueto AM, Puffer ES, Sim A, & Harrison J (2018). An evaluation of a common elements treatment approach for youth in Somali refugee camps. Global Mental Health, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell K, Dorsey S, Gong W, Ostermann J, Whetten R, Cohen JA, Itemba D, Manongi R, & Whetten K (2014). Treating unresolved grief and posttraumatic stress symptoms in orphaned children in tanzania: group-based trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(6), 664–671. 10.1002/jts.21970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ommeren M, Sharma B, Thapa S, Makaju R, Prasain D, Bhattarai R, & Jde Jong (1999). Preparing instruments for transcultural research: use of the translation monitoring form with Nepali-speaking Bhutanese refugees. Transcultural Psychiatry, 36(3), 285–301. 10.1177/136346159903600304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Papernow PL (2013). Surviving and thriving in stepfamily relationships: What works and what doesn’t. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Parra-Cardona JR, Domenech-Rodriguez M, Forgatch M, Sullivan C, Bybee D, Holtrop K, Escobar-Chew AR, Tams L, Dates B, & Bernal G (2012). Culturally adapting an evidence-based parenting intervention for latino immigrants: the need to integrate fidelity and cultural relevance. Family Process, 51(1), 56–72. 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson JE, Edwards TM, & Vakili S (2018). Global mental health: a call for increased awareness and action for family therapists. Family Process, 57(1), 70–82. 10.1111/famp.12281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen GA, Smallegange E, Coetzee A, Hartog K, Turner J, Jordans MJ, & Brown FL (2019). A systematic review of the evidence for family and parenting interventions in low-and middle-income countries: child and youth mental health outcomes. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 2036–2055. [Google Scholar]

- Pote H, Stratton P, Cottrell D, Shapiro D, & Boston P (2003). Systemic family therapy can be manualized: research process and findings. Journal of Family Therapy, 25(3), 236–262. 10.1111/1467-6427.00247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puffer ES, Friis-Healy EA, Giusto A, Stafford S, & Ayuku D (2019). Development and implementation of a family therapy intervention in Kenya: A community-embedded lay provider model. Global Social Welfare, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Puffer ES, Giusto A, Rieder A, Friis Healy E, Ayuku D, & Green EP (2018). Development and validation of a measure of family functioning in Kenya: a diagnostic accuracy study. https://osf.io/ak2nu/.

- Repetti RL, Taylor SE, & Seeman TE (2002). Risky families: family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin, 128(2), 330–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singla DR, Weobong B, Nadkami A, Chowdhary N, Shinde S, Anand A, Fairbum CG, Dimijdan S, Velleman R, Weiss H, & Patel V (2014). Improving the scalability of psychological treatments in developing countries: An evaluation of peer-led therapy quality assessment in Goa, India. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 60, 53–59. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 38, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Alink LRA, & van IJzendoorn MH (2015). The prevalence of child maltreatment across the globe: review of a series of meta-analyses. Child Abuse Review, 24(1), 37–50. 10.1002/car.2353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, & Douglas EM (2004). A short form of the revised conflict tactics scales, and typologies for severity and mutuality. Violence and Victims, 19(5), 507–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF (2012). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, & Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. Violence against children in Kenya: findings from a national survey, 2010 Summary report on the prevalence of sexual, physical and emotional violence, context of sexual violence, and health and behavioral consequences of violence experienced in childhood. Nairobi, Kenya: The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). http://www.unicef.org/esaro/VAC_in_Kenya.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. (2010). Child disciplinary practices at home: Evidence from a range of low- and middle-income countries. New York: UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- Vu NL, Jouriles EN, McDonald R, & Rosenfield D (2016). Children’s exposure to intimate partner violence: a meta-analysis of longitudinal associations with child adjustment problems. Clinical Psychology Review, 46, 25–33. 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson LK, Kaiser BN, Giusto AM, Ayuku D, & Puffer ES (2020). Validating mental health assessment in Kenya using an innovative gold standard. International Journal of Psychology, 55(3), 425–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2019, April 25). Global Health Observatory (GHO) data repository: Mental health. https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.MHHR?lang=en [Google Scholar]