Abstract

Nutraceuticals have taken on considerable significance due to their supposed safety and possible nutritional and medicinal effects. Pharmaceutical and dietary companies are conscious of monetary success, which benefits healthier consumers and the altering trends that result in these heart-oriented value-added products being proliferated. Numerous nutraceuticals are claimed to have multiple therapeutic benefits despite advantages, and unwanted effects encompass a lack of substantial evidence. Several common nutraceuticals involve glucosamine, omega-3, Echinacea, cod liver oil, folic acid, ginseng, orange juice supplemented with calcium, and green tea. This review is dedicated to improving the understanding of nutrients based on specific illness indications. It was reported that functional foods contain physiologically active components that confer various health benefits. Studies have shown that some foods and dietary patterns play a major role in the primary prevention of many ailment conditions that lead to putative functional foods being identified. Research and studies are needed to support the possible health benefits of different functional foods that have not yet been clinically validated for the relationships between diet and health. The term “functional foods” may additionally involve health/functional health foods, foods enriched with vitamins/minerals, nutritional improvements, or even conventional medicines.

1. Introduction

Functional foods and nutraceuticals play an important role in combating and mitigating diseases and disorders related to lifestyles. These foods contain dietary ingredients that help maintain a healthy lifestyle and can even cure some diseases. Food can be considered functional when it has a significant health effect that extends beyond basic traditional nutrition [1]. Nutraceutical products are derived from foods containing the essential components, like functional foods, which have therapeutic effects. Its beneficial components can be isolated and purified from plant, animal, or marine sources. Functional foods and nutraceuticals have attracted international interest and shaped a growing global market. Often referred to as “functional foods,” nutraceuticals have led to intense controversy due to the fact they blur the conventional dividing line between diet and medicine. Therefore, functional food provides the human body with the required quantity of basic needs and essential for healthy survival like proteins, fats, carbohydrates, and vitamins [2]. It is considered “nutraceutical” when functional food helps in disease/disorder prevention and/or medication other than deficiency conditions such as anemia. Therefore, functional food may be used as a nutraceutical to another consumer. Supplemented dairy foods (for example, milk has a nutrient, and its pharmaceutical product is casein) and citrus fruit (orange juice has a nutrient, and its pharmaceutical constituent is ascorbic acid) are examples of nutraceuticals. This review analyses the fundamental concepts of nutraceuticals and functional foods and discusses some of their sources, including fruits, vegetables, cereals, and legumes [2].

2. Nutraceuticals

2.1. Concept of Nutraceuticals

Dr. Stephen DeFelice coined the term (nutraceutical) in the year 1989. A hybrid of nutrients and pharmaceuticals underscores the crossroads between the food and pharmaceutical industries. Nutraceuticals contain nontoxic food components that can cure or prevent disease or an unhealthy condition [3]. The concept is by no means new. Almost 2000 years ago, the Greek physician, the father of medicine, Hippocrates said, “Let your food be your medicine and your medicine be your food.” Nutraceuticals play an important role in biological processes like cell proliferation, antioxidant defense, and gene expression. Nutraceuticals can delay the aging process and decrease the risk of situations like cancer, heart disease, hypertension, excessive weight, high cholesterol, diabetes, osteoporosis, arthritis, insomnia, cataracts, constipation, indigestion, and many other lifestyle-related disorders. Table 1 illustrates the difference between functional foods and nutraceuticals.

Table 1.

Difference between functional foods and nutrients with examples.

| Functional foods | Nutraceuticals |

| The foods with ingredients which give that food health-promoting properties over and above its usual nutritional value | The foodstuff (as a fortified food or a dietary supplement) held to provide health or medical benefits in addition to its basic nutritional value |

| Naturally contain bioactive compounds found in foods | The bioactive compounds found in fortified foods, dietary supplement, or herbal products |

| Natural | Natural or synthetic and available as pills, capsules, or liquids |

| The bioactive compounds in them are different from the traditional nutrients | Include traditional nutrients |

| Grapes, strawberries, and apple are examples | Beta-carotene, lycopene, resveratrol, and ferulic acid are examples |

Source: Mulry [4].

Further, nutraceuticals may be isolated and purified from plant, animal, or marine sources. Advantages of nutraceuticals include a longer half-life period, immediate activity upon intake, ready availability, and few side effects. The product soylife helps in the formation of healthy bones, while xangold in maintaining healthy eyes, betatene in immunity improvement, cholestaid and oatwell in blood cholesterol level reduction, and peptopro in the synthesis of muscle protein [4].

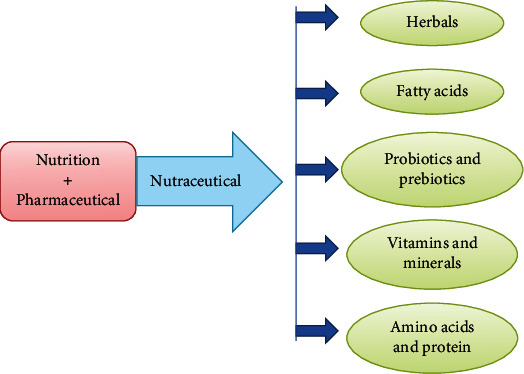

The combined and coordinated action of nutrient components and biologically active compounds is flagged as an indication of a “possible beneficial function” to health. Uses and applications of bioactive components cover a wide range of sectors, especially nutraceuticals [5–7]. In vitro [8] and in vivo [9] studies assessing the beneficial effects of nutraceutical models were presented, in particular studies on the nutritional supplements in animals [10–12]. At the same time, particular researches on botanicals have been described by [13–15] concentrating on the importance of those sources of vegetable origin (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Concept of nutraceuticals [15].

2.2. Nutraceutical History

Nutraceuticals are not new to human culture. In fact, they have evolved along with human evolution as a community. Additionally, we learned from experience the health advantages of herbal products; for example, ayurvedic medicines are in the main nutraceuticals, which again suggest their starting point around 5000 BCE and are still commonly used [16].

2.3. Nutraceutical Ingredients

Probably any natural, beneficial compounds for both therapy and health, they involved dietary fibers, polyphenols, antioxidants, spices, flavonoids, vitamins, probiotics, and polyunsaturated fatty acids [17]. Believing that functional components will assist in the prevention of diseases leads to a positive attitude towards free fatty acid [18].

2.4. Nutraceutical Categorization

Depending on different parameters, many classifications of nutraceuticals were proposed. Depending on the established stage of nutraceuticals [19], nutraceuticals are classified as the following:

Nutraceuticals consist of compounds that offer therapeutic benefit in many types of research/epidemiology studies but are lacking compliance with large-scale clinical research

Established nutraceuticals consist of compounds that exhibit health benefits well supported by clinical data

They can be divided based on the nutraceutical source from which they are extracted or isolated:

Phytochemicals: extracted from plants or herbs such as flavonoids

Microbial extracted nutrients: such as vitamin A

Nutrients of animal origin: extracted from livestock

Divided based on chemical properties, nutraceuticals are classified as

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

Prebiotics

Flavonoids

Vitamins

Additional nutraceuticals are classifiable as the following.

Nutritional Enhancements. These formulas contain nutrients, for example, salt alone or with various preservatives [16].

Functional Foods. These are defined as food enhanced by promoters who promote optimum health and assist in decreasing the disease risk, such as oatmeal containing soluble fiber that reduces cholesterol levels. They are not just nutrients; in brief, they are foods enhanced with nutrients for health benefits [16].

2.5. Nutraceutical Future

Nutraceutical is frequently referred to in the 21st century as a more attractive functional food. By using nutraceutical tools, the physician of the future would have been a better source to offer preventive medical approaches. Nutraceuticals' advances will encourage individualized nutrition personalized to the profile of a person to maximize health and comfort. The nutraceutical market shows that consumers are looking for minimal foods with additional dietary benefits and organoleptic value. In turn, this progress propels the expansion of global nutraceutical markets. In the new millennium, the evolving nutraceutical manufacturing appears destined to occupy the landscape. Its enormous growth and evolution have consequences for food, healthcare, industries of agriculture, and pharmaceutical. As research, exertions continue to unravel the connections between diet and health all over the world. Numerous reviews dealt with the future of nutraceutical markets in the USA, Japan, Europe (pharmaceutical and food opportunities), and Asia (Japan and China) [20].

3. Functional Foods

3.1. Concept of Functional Food

Functional food is described just like any food or food component that can enhance health beyond fundamental nutrition. Such foods reduce the risk of lifestyle-related disorders by achieving physiological functions beyond nutritional effects. These foods are designed either to prevent or to cure the disease [21]. Specifically, the term “functional food” was created in Japan, which was also the first country to enact legislation that brought functional food products to the market. These foods carry the label Food for Specified Health Uses (FOSHU) in Japan, which underscores the therapeutic focus of these products. Food is made functional in several ways. The functional component is added, removed, or modified during processing or via genetic engineering, resulting in new products that are then introduced into the market. Day et al. have reported that the major challenge for functional foods is to ensure that the bioactive constituents remain stable during processing and storage. Vitamins, fiber, omega-3 fatty acids, minerals, bacterial cultures, and flavonoids are components that can add functionality to any kind of food that is produced [22, 23]. The regular consumption of such foods will help efficiently manage diseases like cardiovascular disease (CVD), tumor, diabetes, and hypertension [24–26]. Table 2 illustrates the various types of common functional foods.

Table 2.

Various types of functional foods.

| Type | Description | Example |

|

| ||

| Enriched food products | Adding new nutrients or ingredients that are not usually found in food | Fruit juice enriched with calcium, foods with probiotics and prebiotics |

|

| ||

| Enhanced food commodities | Changes in raw materials that altered the nutrient composition | Carotenoid-containing potatoes, high-lysine corn |

|

| ||

| Fortified food products | Increase the content of nutrients present | Grain products fortified with folic acid, fruit juice with extra VC |

|

| ||

| Altered food products | Change existing components with beneficial components | Low-fat foods with fat replacers |

Source: Spence [27].

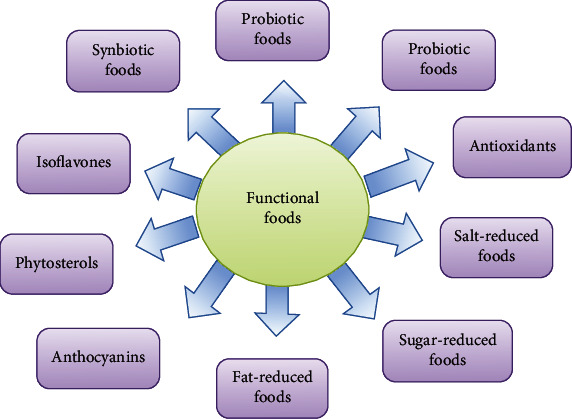

Likewise, many authors have declared about the potential functional foods or their ingredients based on in vitro and animal experiments [27–30], while others misunderstand the difference between conventional and functional foods [31, 32]. Therefore, it is necessary to be aware that functional foods are not medication products, as they do not heal, cure, or prevent diseases (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Establishing functional foods [32].

3.2. Functional Dairy Products

Functional dairy products have undergone an advance as food developed well beyond the fulfillment of the primary needs and were claimed as a treatment aid for primary deficiency syndromes to reduce the risk of disease [33]. Novel yogurt-like products were manufactured using common yogurt starter culture as single or mixed with Bifidobacterium longum (ATCC15707) without additives (control) to produce novel functional yogurt-like products [34, 35]. Functional dairy products pose a major challenge to food manufacturing, as the dairy market is already the area where functional foods are more important than incidents and commercial success. Dairy products may be included in the functional food group due to their calcium content, different proteins that improve health, sphingolipids, butyric acid, conjugated linoleic acid, and probiotic cultures [36, 37]. The dairy product industry is well positioned to develop and take advantage of the functional food market [38]. As individuals come to be more health-conscious and more aware of the role nutrition plays in their diets, this opportunity is further enhanced. Consumers want to get further control over their health.

However, the purchaser will now not compromise on taste or product first-class for health products and the rate is a necessary determining factor for repeated purchase. A principal feature of dairy products is that customers already know them, and many accept that dairy products are healthy natural products. Health professionals international inspire a client to eat at various balanced weight loss programs as an alternative than instant solutions being sought, and dairy products are prominent factors for healthy balanced diets. Milk and dairy products make up one of the four predominant groups of meals that form a balanced diet. Moreover, milk is a significant source of protein, B-group vitamins, and calcium in a varied diet and contains vitamin A, thiamine B1, niacin B3, dimethylglycine B16, folate B9, magnesium, and zinc [39]. Marketing “healthy” food has met with market success in the last two decades. Despite the increasing popularity of functional foods, scientists have identified some particular substance or combination of substances that have demonstrated a reduction in disease risk [40, 41]. Furthermore, the addition of a bioactive ingredient to food creates some functional foods. Adding an external ingredient can have an impact on total product acceptance. Many researchers have examined the acceptance by consumers of new functional ingredients of dairy products via using the scale of food neophobia [42], originally suggested by [43]. Gastrointestinal functions are among the most promising aims for functional foods, involving those that control the transit time, intestinal habits, and motility of the intestinal mucosa as well as those that modulate epithelial cell proliferation. Digestive functions are also promising goals related to balanced microflora related to controlling the bioavailability of nutrients, modulating the immune activity of the digestive system, or mediating endocrine activity of the digestive system.

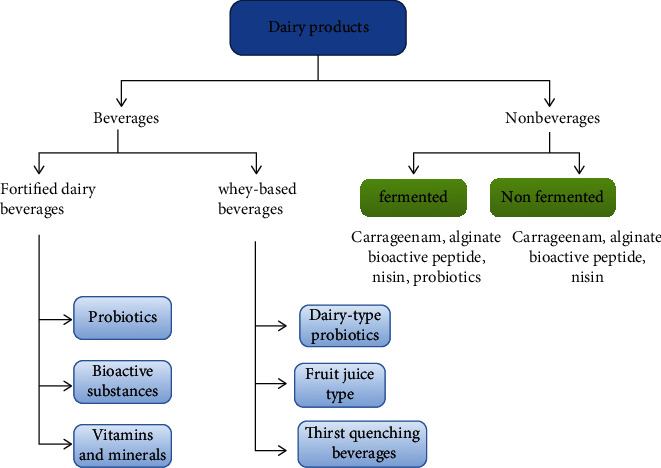

Several systemic functions like lipid homeostasis indirectly influenced by the digestion or fermentation of nutrients are important targets [44, 45]. Darwish has studied the production of functional fermented dairy products using probiotic bacteria isolated from different dairy sources [46]. High-quality empirical evidence research showed that food neophobia is adversely correlated with the willingness of consumers to buy probiotic yogurt. However, this does not affect the willingness of consumers required to purchase other nondairy functional products. Food neophobia with various combinations of functional components can likely play a different role. On the other side, the findings could be complicated by the reality that there is a cholesterol-reducing “virtual prescription” drug for customers with elevated blood cholesterol rates and that therapeutic device developed to reduce neophobia or perception of risk [47] (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Dairy products.

3.3. Probiotics in Dairy Products

In recent years, the demand for the use of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) as probiotics has been growing. In addition to acid and bile resistance, the key trait for a LAB strain to be a probiotic is the capacity to generate antimicrobial compounds in opposition to pathogenic and cariogenic bacteria and to bind to and colonize the intestinal mucosa of humans. Moreover, the development of antimicrobial compounds supports the colonization of probiotics in intestine mucosa via raising their competitive benefit over normal gastrointestinal microflora. Research has proven that capsular polysaccharides could encourage adherence of bacteria to biological surfaces and, thus, facilitate the colonization of different ecological niches [48]. Many of the health benefits of probiotics consist of stimulating immunity, playing an adjunctive role to a vaccine, adhering to cells in the human gut, and increasing aiding in the production of vitamin K and vitamin B, as well as strengthening the protective barrier of the digestive system and preventing diarrhea caused by radiation therapy as antibiotics for rotavirus and C. Furthermore, it is effective in the treatment of constipation, prevention of inflammatory intestinal disorders, and anticancer action, as well as reduces blood pressure and lowers cholesterol [49]. Research has revealed that certain lactobacilli strains have antioxidant activity and may decrease the risk of accumulation of free radicals [50]. Furthermore, probiotics modulate inflammatory and hypersensitivity responses. This may be because of cytokine function regulation. They prohibit reoccurrences of inflammatory intestinal disorder in adults as well as improved milk allergies and reduce children's eczema risk. Probiotics improve the allocation of immune function by increasing the number of plasma cells developing IgA, increasing or enhancing phagocytosis, and raising the ratio of natural killer cells and T lymphocytes [51]. Due to the production of the Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, such as peptides during fermentation, the intake of fermented milk with different LAB strains can lead to moderate blood pressure reductions [52].

In animals, lowering the serum cholesterol levels through probiotics can presumably be achieved by decomposing bile in the intestines, thereby preventing its reabsorption. This can lead to modest reductions in total cholesterol and LDL levels [53]. Most probiotics have been used for GIT-related diseases; however, some studies have probiotics assessed in allergic conditions, along with dermatitis, rhinitis, vaginosis, and allergies to foodstuffs. Atopic dermatitis, known as eczema, is the most popular of skin disorders. Studies have proven that probiotics, such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, may forestall or decrease the symptoms. In addition, eczema can be avoided if moms eat probiotics for the duration of their pregnancy and if neonates consume it during the first six months of their existence [54]. Probiotics like Lactococcus, Leuconostoc, and Pediococcus can prohibit or restrict cycotoxinogenic mildew increase [55]. Besides, LAB could bind aflatoxin B1 both in vivo and in vitro according to their bacterial strain [56]. Previous studies suggested that Lactobacillus paracasei reduces body and belly fat. Apparently, these probiotics have an antiobesity effect [57]. Most possibly, intestinal bacteria can control body weight by influencing the metabolic neuroendocrine and immune functions of the host [56].

3.4. Probiotic Yogurt as a Functional Food

Yogurt is a result of milk fermentation with lactic acid by adding a common starter culture that includes Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus. Less typical microorganisms in some countries, like Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. lactis and Lactobacillus helveticus, often mixed with a mixture of starters [58]. Currently, the market provides a wide range of yogurts suitable for all palates and meal occasions. Yogurts come in a diversity of textures (like liquid, stirred, and set), flavors (like natural, fruit, and cereal), and fat contents (like luxury, low-fat, and fat-free); can be enjoyed like a snack or as part of a meal, like sweet or savory snacks; and are available throughout the year. Together with their recognition as healthy and nutritious food, this versatility contributed to their widespread success in all subgroups of the population. Introducing probiotic strains to yogurt is a good approach to produce effective, acceptable, and affordable fermented milk. However, introducing new strains to yogurt starter culture may affect the acidity, aroma perceptions, and textural properties of the product. The texture is a critical aspect of yogurt that is acceptable to consumers. Rheological properties affect the texture that affects sensory perception and ultimately consumer acceptance of a product [59–61]. Functional properties of microorganisms in fermented foods contain probiotics [62], antioxidants [63], antimicrobials [64], peptide production [65], polyglutamic acid [66], fibrinolytic activity [67], and antinutritional compound degradation [68]. Proteolytic microorganisms through food fermentation [65], which exhibits certain functional properties like immunomodulatory properties [69], antihypertensive properties [70], and antithrombic properties [71], form bioactive peptides.

3.5. Health Benefits of Functional Foods

Marco et al. described that enhanced nutritional and functional properties of fermented foods maybe because of the transformation of substrates and formation of bioactive or bioavailable end products [72], while Sarkar confirmed the most promising targets of functional foods as [73]

intestinal function including those control transit time, bowel habits, mucosal motility, and modulation of epithelial cell proliferation

gastrointestinal (GI) function that is associated with a balanced colonic microflora, control of nutrient bioavailability, and modification of GI immune activity or that is mediated by the endocrine activity of the GI system

systemic function such as lipid homeostasis that is indirectly influenced by the nutrient dosage or fermentation

Further, he also highlighted the extension of the following health benefits to human beings due to the consumption of functional foods [73]:

Reduced risk of cardiovascular disease

Reduced risk of cancer

Improved health in general

Improved memory

Improved weight loss/management

Reduced risk of other diseases

Reduced osteoporosis

Improved mental health

Quicker reaction time

Improved fetal health

3.6. Health Benefits of Nutraceuticals

Nutraceuticals are used in an attempt to accomplish desirable therapeutic outcomes with reduced side effects, as compared with other therapeutic agents. Consumption of plant-based foods, nuts, whole grains, cereals, and marine foods plays a vital role in disease prevention and health promotion [74, 75]. Some popular nutraceuticals include lutein (for macular degeneration), folic acid, and cod liver oil capsules. The most popular functional food and beverage products include omega-3 eggs, omega-3-enriched yogurts, calcium-enriched orange juice, and green tea, to mention a few.

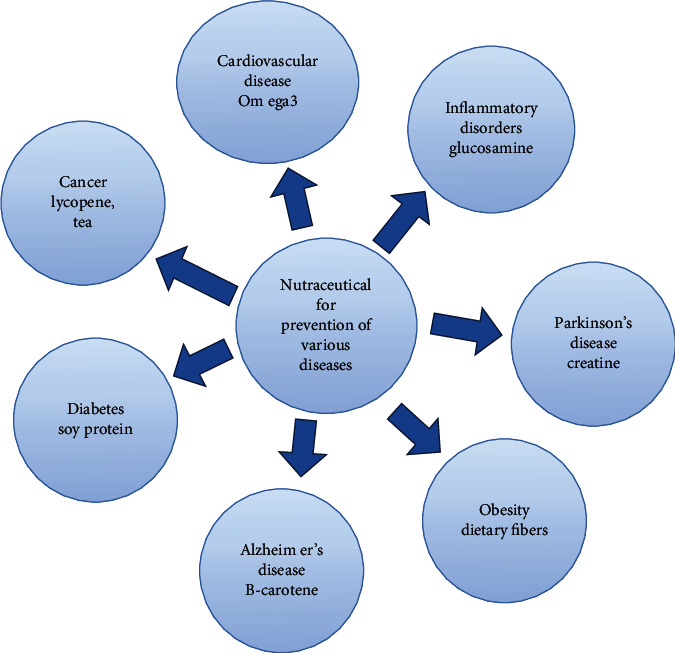

The majority of the nutraceuticals do possess multiple therapeutic benefits. Nutraceuticals are claimed to possess physiological benefit or protection (Figure 4) against the following diseases:

CVD

Cancer

Diabetes

Obesity

Chronic inflammatory disorders

Parkinson's disease

Alzheimer's disease

Figure 4.

Nutraceuticals used in prevention of various diseases [74].

4. Conclusion

The goal of this article is to encourage medical and health professionals to expand their knowledge of the properties of functional foods as they promote good health while helping to prevent disease. Functional foods that contain physiologically active ingredients can improve health, from either animal or plant sources; by supporting health through prevention rather than treatment, nutraceuticals and functional foods could provide a solution to reduce the growing burden on health care systems, although it is important to note that functional foods are not medications, as they do not heal, cure, or prevent diseases. However, nutraceutical products are expected to play a major role in potential therapeutic development. Society health authorities regard nutraceutical as prevention, therapy, and a powerful tool for preserving health and acting versus acute and chronic diseases caused by nutrition, thereby enhancing health. Nutraceuticals are developing in clinical practice, but advanced studies need to address the importance of pharmaceutical and clinical issues.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Fund (81160546).

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Wildman R. E. Handbook of Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods. 1st. 2001. CRC Series in Modern Nutrition.

- 2.Wildman R. E. C., Kelley M. Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2007. Handbook of Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ross S. Functional foods: the Food and Drug Administration perspective. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2000;71:1735–1738. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.6.1735S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mulry M. Functional foods & nutraceuticals. Issue nutritional science news; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santini A. Nutraceuticals: redefining a concept. Ann. Pharmacol. Pharm. 2018;3:p. 1147. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santini A., Novellino E. Nutraceuticals: beyond the diet before the drugs. Current Bioactive Compounds. 2014;10(1):1–12. doi: 10.2174/157340721001140724145924. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng L., Khalaf A. T., Lin T., et al. Exercise promotes the osteoinduction of HA/β-TCP biomaterials via the Wnt signaling pathway. Metabolites. 2020;10(3):p. 90. doi: 10.3390/metabo10030090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu W. N., Shi J., Fu Y., Zhao X. H. The stability and activity changes of apigenin and luteolin in human cervical cancer Hela cells in response to heat treatment and Fe2+/Cu2+ addition. Food. 2019;8(8):p. 346. doi: 10.3390/foods8080346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sayed S., Ahmed M., el-Shehawi A., et al. Ginger water reduces body weight gain and improves energy expenditure in rats. Food. 2020;9(1):p. 38. doi: 10.3390/foods9010038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Omri B., Amraoui M., Tarek A., et al. Arthrospira platensis (spirulina) supplementation on laying hens’ performance: eggs physical, chemical, and sensorial qualities. Food. 2019;8(9):p. 386. doi: 10.3390/foods8090386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Omri B., Larbi Manel B., Jihed Z., et al. Effect of a combination of fenugreek seeds, linseeds, garlic and copper sulfate on laying hens performances, egg physical and chemical qualities. Food. 2019;8(8):p. 311. doi: 10.3390/foods8080311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khalaf A. T., Sun Y., Wang F., Sheng M., Li Y., Liu X. Photodynamic therapy using HMME for port-wine stains: clinical effectiveness and sonographic appearance. BioMed Research International. 2020;2020:7. doi: 10.1155/2020/6030581.6030581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fredes C., Parada A., Salinas J., Robert P. Phytochemicals and traditional use of two southernmost Chilean berry fruits: Murta (Ugni molinae Turcz) and Calafate (Berberis buxifolia Lam.) Food. 2020;9(1):p. 54. doi: 10.3390/foods9010054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ji M. Y., Bo A., Yang M., et al. The pharmacological effects and health benefits of Platycodon grandiflorus—a medicine food homology species. Food. 2020;9(2):p. 142. doi: 10.3390/foods9020142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapoor N., Jamwal V. L., Shukla M. R., Gandhi S. G. The rise of nutraceuticals: overview and future. In: Saxena A., editor. Biotechnology Business - Concept to Delivery. EcoProduction (Environmental Issues in Logistics and Manufacturing) Cham: Springer; 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh S., Razak M. A., Sangam S. R., Viswanath B., Begum P. S., Rajagopal S. Therapeutic Foods. Academic Press; 2018. The impact of functional food and nutraceuticals in health; pp. 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Das L., Bhaumik E., Raychaudhuri U., Chakraborty R. Role of nutraceuticals in human health. Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2012;49(2):173–183. doi: 10.1007/s13197-011-0269-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chamas R., El-Hayek J., Fatayri M., Makdissi R., Bou-Mitri C. Consumer knowledge and attitudes toward functional foods in Lebanon. Nutrional Food Science. 2019;49(4):762–776. doi: 10.1108/NFS-09-2018-0263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pandey M., Verma R. K., Saraf S. A. Nutraceuticals: new era of medicine and health. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research. 2010;3(1):11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taha Khalaf A., Song J. Q., Gao T. T., Yu X. P., Lei T. C. CTLA-4 gene polymorphism and the risk of systemic lupus erythematosus in the Chinese population. Journal of Biomedicine & Biotechnology. 2011;2011:6. doi: 10.1155/2011/167395.167395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberfroid M. B. Prebiotics and probiotics: are they functional foods? The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2000;71(6):1682S–1687S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.6.1682S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Day L., Seymour R. B., Pitts K. F., Konczak I., Lundin L. Incorporation of functional ingredients into foods. Trends in Food Science and Technology. 2009;20(9):388–395. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2008.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keservani R. K., Vyas N., Jain S., Raghuvanshi R., Sharma A. K. Nutraceutical and functional food as future food: a review. Der Pharmacia Lettre. 2010;2:p. 106. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown L., Caligiuri S. P., Brown D., Pierce G. N. Clinical trials using functional foods provide unique challenges. Journal of Functional Foods. 2018;45:233–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2018.01.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cassidy Y. M., McSorley E. M., Allsopp P. J. Effect of soluble dietary fibre on postprandial blood glucose response and its potential as a functional food ingredient. Journal of Functional Foods. 2018;46:423–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2018.05.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mak K. K., Tan J. J., Marappan P., et al. Galangin's potential as a functional food ingredient. Journal of Functional Foods. 2018;46:490–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2018.04.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spence J. T. Challenges related to the composition of functional foods. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 2006;19:S4–S6. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2005.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Çalışkantürk Karataş S., Günay D., Sayar S. _In vitro_ evaluation of whole faba bean and its seed coat as a potential source of functional food components. Food Chemistry. 2017;230:182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gouw V. P., Jung J., Zhao Y. Functional properties, bioactive compounds, and _in vitro_ gastrointestinal digestion study of dried fruit pomace powders as functional food ingredients. LWT. 2017;80:136–144. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.02.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rana S., Gupta S., Rana A., Bhushan S. Functional properties, phenolic constituents and antioxidant potential of industrial apple pomace for utilization as active food ingredient. Food Science and Human Wellness. 2015;4(4):180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.fshw.2015.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fedacko J., Singhal S., Singh R. B., Hristova K., Itharat A., Halabi G. The Role of Functional Food Security in Global Health. Academic Press; 2019. Functional food security for prevention of cardiovascular diseases; pp. 167–183. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Homayouni A., Alizadeh M., Alikhah H., Zijah V. Functional dairy probiotic food development: trends, concepts, and products. Immunology and Microbiology:“Probiotics”. 2012. pp. 197–212. https://www.intechopen.com/books/probiotics/functional-dairy-probiotic-food-development-trends-concepts-and-products. [DOI]

- 33.Palmer G. The politics of breastfeeding: when breasts are bad for business. third edition. Pinter & Martin Publishers; 2009. part (1) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ayad E. H. E., Darwish A. M. G., Darwish S. M., El-Soda M. Production of novel functional yoghurt-like products. Egyptian Journal of Dairy Scince. 2010;38:183–199. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Darwish A. M. G., Ayad E. H. E., Darwish S. M., El-Soda M. Production of healthy fermented milk. Cairo, Egypt: Patent Office, Academy of Scientific Research and Technology, Ministry of Scientific Research; 2010. No 2009081233 EG. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalamian M. Keto for cancer: ketogenic metabolic therapy as a targeted nutritional strategy. Chelsea Green Publishing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Torrence P. F. Molecules of nature: biodiversity, the sixth mass extinction and the future of medicine. Dog Ear Publishing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aadinath T., Amaladhas P., Anandharamakrishnan C. Dried dairy products and their trends in the global market. Handbook of Drying for Dairy Products. 2017;15:339–344. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tamime A. Y., Thomas L. Probiotic Dairy Products. John Wiley & Sons; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Popkin B. M., Kenan W. Preventing type 2 diabetes: changing the food industry. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2016;30(3):373–383. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khalaf A. T., Feng L. L., Samiah A. K., et al. Integrative and holistic approach for immunological disorders using electroacupuncture. International Journal of Applied Business and Economic Research. 2017;15:255–261. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bimbo F., Bonanno A., Nocella G., et al. Consumers' acceptance and preferences for nutrition-modified and functional dairy products: a systematic review. Appetite. 2017;113:141–154. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pliner P., Hobden K. Development of a scale to measure the trait of food neophobia in humans. Appetite. 1992;19(2):105–120. doi: 10.1016/0195-6663(92)90014-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roberfroid M. B. Functional effects of food components and the gastrointestinal system: chicory fructooligosaccharides. Nutrition Reviews. 1996;54(11 Part 2):S38–S42. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1996.tb03817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khalaf A. T., Junhua L., Wang Y., et al. Emotional and social wellbeing in middle and primary schools: Hubei, China. Research Journal of Medical Sciences. 2017;11:138–142. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Darwish A. M. G. Production of functional fermented dairy products using probiotic bacteria isolated from different dairy soirces, Ph.D. Thesis. Egypt, Alexandria: Food Science, Alexandria University; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khalaf A. T., Li W., Jinquan T. Current advances in the management of urticaria. Archivum immunologiae et therapiae experimentalis. 2008;56(2):103–114. doi: 10.1007/s00005-008-0013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Floch M. H., Hong-Curtiss J. Probiotics and functional foods in gastrointestinal disorders. Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology. 2002;5:311–321. doi: 10.1007/s11938-002-0054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andersson H., Asp N. G., Bruce Å., Roos S., Wadström T., Wold A. E. Health effects of probiotics and prebiotics a literature review on human studies. Näringsforskning. 2016;45(1):58–75. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Y., Wu Y., Wang Y., et al. Antioxidant properties of probiotic bacteria. Nutrients. 2017;9(5):p. 521. doi: 10.3390/nu9050521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bodera P., Chcialowski A. Immunomodulatory effect of probiotic bacteria. Recent Patents on Inflammation & Allergy Drug Discovery. 2009;3(1):58–64. doi: 10.2174/187221309787158461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rai A. K., Sanjukta S., Jeyaram K. Production of angiotensin I converting enzyme inhibitory (ACE-I) peptides during milk fermentation and their role in reducing hypertension. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2017;57(13):2789–2800. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2015.1068736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Granato D., Branco G. F., Cruz A. G., Faria J. D. A. F., Shah N. P. Probiotic dairy products as functional foods. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2010;9(5):455–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2010.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Collado C. M., Gueimonde M., Pirez-Marinez G. Current and future applications of probiotics. Current Nutrition & Food Science. 2011;7(3):170–180. doi: 10.2174/157340111797264877. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blagojev N., Škrinjar M., Vesković-Moračanin S., ŠoŠo V. Control of mould growth and mycotoxin production by lactic acid bacteria metabolites. Romanian Biotechnological Letters. 2012;17:7219–7226. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zuo R. Y., Chang J., Yin Q. Q., et al. Effect of the combined probiotics with aflatoxin B1-degrading enzyme on aflatoxin detoxification, broiler production performance and hepatic enzyme gene expression. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2013;59:470–475. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tanida M., Shen J., Maeda K., et al. High-fat diet-induced obesity is attenuated by probiotic strain _Lactobacillus paracasei_ ST11 (NCC2461) in rats. Obesity Research & Clinical Practice. 2008;2(3):159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tamime A. Y. Fermented milks: a historical food with modern applications-a review. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2002;56(S4):S2–S15. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Soukoulis C., Panagiotidis P., Koureli R., Tzia C. Industrial yogurt manufacture: monitoring of fermentation process and improvement of final product quality. Journal of Dairy Science. 2007;90(6):2641–2654. doi: 10.3168/jds.2006-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang L., Khalaf A. T., Lei D., et al. Structured oral examination as an effective assessment tool in lab-based physiology learning sessions. Advances in Physiology Education. 2020;44(3):453–458. doi: 10.1152/advan.00059.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hill C., Guarner F., Reid G., et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2014;11(8):506–514. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perna A., Intaglietta I., Simonetti A., Gambacorta E. Effect of genetic type and casein haplotype on antioxidant activity of yogurts during storage. Journal of Dairy Science. 2013;96(6):3435–3441. doi: 10.3168/jds.2012-5859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tang Y., Khalaf A. T., Liu X., et al. Zinc finger A20 and NF-κB correlate with high-risk human papillomavirus of squamous cell carcinoma patients. Tumor Biology. 2014;35(12):11855–11860. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2416-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meira S. M. M., Helfer V. E., Velho R. V., Lopes F. C., Brandelli A. Probiotic potential ofLactobacillusspp. isolated from Brazilian regional ovine cheese. Journal of Dairy Research. 2012;79(1):119–127. doi: 10.1017/S0022029911000884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.De Mejia E. G., Dia V. P. The role of nutraceutical proteins and peptides in apoptosis, angiogenesis, and metastasis of cancer cells. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2010;29(3):511–528. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chettri R., Tamang J. P. Functional properties ofTungrymbaiandBekang, naturally fermented soybean foods of north East India. International Journal of Fermented Foods. 2014;3(1):87–103. doi: 10.5958/2321-712X.2014.01311.8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kotb E. Fibrinolytic Bacterial Enzymes with Thrombolytic Activity. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2012. Fibrinolytic Bacterial Enzymes with Thrombolytic Activity; pp. 1–74. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Babalola O. O. Cyanide content of commercial gari from different areas of Ekiti State, Nigeria. World Journal of Nutrition and Health. 2014;2(4):58–60. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Qian B., Xing M., Cui L., et al. Antioxidant, antihypertensive, and immunomodulatory activities of peptide fractions from fermented skim milk withLactobacillus delbrueckiissp.bulgaricusLB340. Journal of Dairy Research. 2011;78(1):72–79. doi: 10.1017/S0022029910000889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Phelan M., Kerins D. The potential role of milk derived peptides in cardiovascular diseases. Food & Function. 2011;2(3/4):153–167. doi: 10.1039/c1fo10017c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Singh T. A., Devi K. R., Ahmed G., Jeyaram K. Microbial and endogenous origin of fibrinolytic activity in traditional fermented foods of Northeast India. Foodservice Research International. 2014;55:356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2013.11.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Marco M. L., Heeney D., Binda S., et al. Health benefits of fermented foods: microbiota and beyond. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2017;44:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sarkar S. Potential benefits of probiotics for preterm infants: a review. Journal of Nutritional Therapeutics. 2016;5(2):55–63. doi: 10.6000/1929-5634.2016.05.02.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Khalaf A. T., Wan J., Al-Jashamy K., et al. Nicotine replacement therapy and electronic cigarettes: awareness among medical students. Journal of Pharmaceutical Research International. 2019;31(2):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rajasekaran A., Sivagnanam G., Xavier R. Nutraceuticals as therapeutic agents: A Review. Research Journal of Pharmacy and Technology. 2008;1(4):328–340. [Google Scholar]