Abstract

To examine whether patients with inflammatory arthritis (IA) treated with conventional synthetic (cs) disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and/or biologic (b) DMARDs, could be affected from SARS-CoV-2 infection and to explore the COVID-19 disease course and outcome in this population. This is a prospective observational study. During the period February–December 2020, 443 patients with IA who were followed-up in the outpatient arthritis clinic were investigated. All patients were receiving cs and/or bDMARDs. During follow-up, the clinical, laboratory findings, comorbidities and drug side effects were all recorded and the treatment was adjusted or changed according to clinical manifestations and patient’s needs. There were 251 patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), 101 with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and 91 with ankylosing spondylitis (AS). We identified 32 patients who contracted COVID-19 (17 RA, 8 PsA, 7 AS). All were in remission and all drugs were discontinued. They presented mild COVID-19 symptoms, expressed mainly with systemic manifestations and sore throat, while six presented olfactory dysfunction and gastrointestinal disturbances, and all of them had a favorable disease course. However, three patients were admitted to the hospital, two of them with respiratory symptoms and pneumonia and were treated appropriately with excellent clinical response and outcome. Patients with IA treated with cs and/or bDMARDs have almost the same disease course with the general population when contract COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, Rheumatoid arthritis, Psoriatic arthritis, Ankylosing spondylitis, Autoimmune rheumatic disease

Introduction

The coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by the severe respiratory coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection has been proven to affect mostly the vulnerable population [1, 2]. Among them are patients suffering from autoimmune rheumatic diseases (ARD) and especially those using immunosuppressive drugs like conventional synthetic (cs) disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), biological (b) DMARDs and corticosteroids [3]. However, whether or not patients with ARDs, such as patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and ankylosing spondylitis (AS), are at an increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection, or of severe COVID-19 disease, remains unclear. ARDs are highly heterogeneous regarding the clinical features, the systemic manifestations, related comorbidities and most important the use of cs, bDMARDs and/or corticosteroids. Recent data show that patients with RA, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and psoriasis, when contract the COVID-19 had higher ratios of death when analyzed as a group, compared to people without the above diseases, especially those receiving high doses of corticosteroids [4]. On the other hand, there are studies showing that in patients with ARDs and SARS-CoV-2 infection the disease is expressed with mild clinical symptoms without severe consequences, due to the use of cs and bDMARDs [5–7].

Current data, demonstrated that many cytokines mostly tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFa), interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and various chemokines, play a pivotal role in the pathological response seen in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients [8, 9]. On the other hand, these cytokines are the target for the treatment of several ARDs. Thus, cytokine inhibitors used to treat RA, PSA and AS are of interest in terms of whether they can be an effective treatment for severe COVID-19 disease and whether their chronic use in patients with rheumatic diseases might alter the course of SARS-CoV-2 infection. In addition, the potential role of csDMARDs, such as hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), in the presentation, severity, and even management of COVID-19 disease has received considerable attention [10, 11]. For this reason, we examined whether patients with inflammatory arthritides (IA), mostly RA, PsA, and AS treated with csDMARDs and/or bDMARDs could be affected from SARS-CoV-2 infection and to explore the COVID-19 disease course and outcome in this population, in a prospective observational study.

Materials and methods

This is a single-center prospective observational study. During the period February–December 2020, all patients with IA who were followed-up in the outpatient arthritis clinic were investigated. All patients were receiving csDMARDs and/or bDMARDs and some were receiving corticosteroids. They were followed-up at predefined times, initially every month and every 2, or 3 months thereafter. During follow-up, all the clinical and laboratory findings, but also any comorbidities and drug adverse events were recorded and the treatment was adjusted or changed according to clinical manifestations and patient needs.

Inclusion criteria

Patients with IA receiving cs and/or bDMARDs with or without small doses of corticosteroids (CRs), usually prednisone < 7.5 mg/day.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with other ARD like SLE, scleroderma, dermatomyositis not receiving cs and/or bDMARDs and patients receiving high doses of CRs > 7.5 mg/day.

Disease definition

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is defined as an illness caused by the novel coronavirus now called severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), diagnosed with positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [1, 2].

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Results

A total of 443 patients with IA were examined and followed-up until December 2020. There were 251 RA, 101 PsA and 91 AS. We identified 32 patients who contracted COVID-19 (17 RA, 8 PsA, 7 AS). From the RA group, (mean age 59.5 ± 6.3 years) 4 were on methotrexate (MTX) monotherapy plus prednisone 2.5 mg/day, 2 on leflunomide (LFN) monotherapy plus prednisone 2.5 mg/day, 7 on anti-TNFa therapy (2 in combination with MTX), 2 on tofacitinib and 1 on tocilizumab. From the PsA group (mean age 51.4 ± 4.2 years), 3 were on MTX monotherapy and 5 on TNFa inhibitors, while all AS patients (mean age 37.6 ± 5.1 years) were receiving TNFa inhibitors. All patients were in remission when contracted COVID-19 and presented mild symptoms expressed mainly as myalgias, arthralgias, low-grade fever, and sore throat, while six presented also olfactory dysfunction and gastrointestinal disturbances. The laboratory tests revealed only high acute phase reactants mostly C-reactive protein (CRP) and/or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). None of the patients developed hyperferritenemia and hyper-fibrinogenemia and none had leukopenia (Table 1). The treatment was discontinued except prednisone and all patients were advised to remain isolated at home without any additional therapy. After a week, the majority of them felt well and 2 weeks later all were free of their symptoms and the tests for SARS-CoV-2 were negative. However, three patients developed dry cough, dyspnea and fever until 38, 8 °C and were hospitalized. One had a short in-hospital stay after responding very well to antiviral (remdesivir) and antibiotics (azithromycin) therapy. However, two of them developed pneumonia and were treated appropriately. None was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) and after 2 weeks were discharged with negative tests for SARS-CoV-2. We present shortly the disease course of these two patients.

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory findings of patients with IA and COVID-19

| Disease, N | Systemic manifestations, Ν (%) | Ear, nose and throat symptoms, N (%) | Respiratory manifestations, N (%) | Other manifestations, N (%) | Laboratory tests, N (%) | Hospitalization, N (%) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA:17 | Arthralgias, myalgias and low-grade fever 15 (88) | Sore throat 3 (18) Olfactory dysfunctions 3 (18) | 2 (12) | Abdominal pain, diarrhea 2 (12) |

High CRP:13 (76) High ESR:10 (59) |

2 (12) | Very good |

| PSA:8 |

Arthralgias, myalgias 8 (100) Low grade fever 7 (62.5) |

Sore throat 2 (25) Olfactory dysfunctions 1 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) | Abdominal pain 2 (25) |

High CRP:6 (75) High ESR:3 (37.5) |

1 (12.5) | Very good |

| AS:7 |

Arthralgias, myalgias 6 (86) Low grade fever 3 (43) |

Sore throat 1 (14) Olfactory dysfunction 2 (29) |

None | Abdominal pain and diarrhea 2 (29) |

High CRP 5 (71) High ESR 3 (43) |

None | Very good |

IA inflammatory arthritis, N number of patients, % percent, RA rheumatoid arthritis, PSA psoriatic arthritis, AS ankylosing spondylitis, CRP C-reactive protein, ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate

Case 1

The first patient was a 55-year-old male with seropositive RA and no other comorbidities. He was on MTX monotherapy on a dosage of 12.5 mg/week since 2017 with a favorable disease course. This patient developed dry cough and dyspnea, along with fever up to 39 °C. MTX was discontinued. The oxygen saturation on air was 88%. Chest X-rays showed a large consolidation with moderate effusion affecting the base of the right lung, which was confirmed by computed tomography (CT) scan. He was admitted to the hospital where he received azithromycin plus remdesivir and dexamethasone, along with anakinra 100 mg/day subcutaneously [12]. Two weeks later, he felt much better and the oxygen saturation was 95% on air. Chest X-rays showed resolution of the consolidation and he was then discharged from the clinic with negative SARS-CoV-2 test.

Case 2

The second case was a 60-year-old male with seropositive RA on combination therapy with adalimumab (ADA) and leflunomide (LFN) plus 2.5 mg of prednisolone. A low disease activity has been recorded on the last follow-up. Hyperlipidemia treated with rosuvastatin was the only comorbidity. After being tested positive for COVID-19 with mild symptoms (ADA + LFN were stopped) and on day 14, he developed bilateral pneumonia with lung effusions, significant dyspnea and fever. Oxygen saturation on air was 85%. Despite the 7-day hospitalization, he lastly responded well and fully responded to a combination therapy of remdesivir, azithromycin, dexamethasone and anticoagulant therapy [12]. Ten days later, he had a significant improvement without dyspnea, the oxygen saturation on air was 96% and the new chest X-rays showed significant radiographic improvement. After the favorable course of the disease, he was discharged from the clinic with a negative SARS-CoV-2 test.

Furthermore, from February to May 2020 in 11 out of 32 patients, serum IgG antibodies to COVID-19 were measured approximately 20 days after a negative PCR test and in 6 months since the first positive test to the virus. All patients had high titers of antibodies in their serum.

Discussion

During the COVID-19 pandemic, all categories of individuals have been affected, either being previously healthy, or being treated for any kind of disease, but vulnerable patients seem to be affected more. In the current manuscript, we present 32 patients with IA that developed the COVID-19 disease.

What is interesting in our study is that the majority of patients who contracted COVID-19 presented a mild disease course, expressed mostly with systemic clinical manifestations and mild upper respiratory symptoms with a favorable clinical course. Only three patients were admitted to the hospital, two with respiratory symptoms who were recovered completely (Table 1).

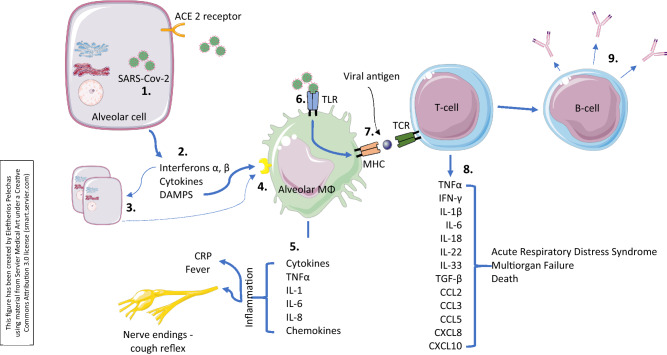

As far as it concerns the pathophysiology of the COVID-19 infection, on one side, host’s immune response is necessary for the resolution of the infection, but on the other hand, it can prove detrimental leading to several complications, some of them fatal. The SARS-CoV-2 infection leads to a downregulation of the ACE2 expression leading to a high production of angiotensin 2 from the ACE enzyme. Stimulation of the ACE2 receptor type 1a increases the pulmonary vascular permeability, and this could be the explanation to the potentially augmented pulmonary damage when the expression of the ACE2 is decreased [13]. Additionally, the virus activates the adaptive immune response, where the activated Th-1 cells can stimulate the cytotoxic CD8+ T-cells to destroy them. Th-1 cells activate and stimulate the B-cells to produce specific antibodies to the antigens [14, 15]. Despite this defensive mechanism, like the SARS-CoV 2002, these viruses have the ability of bypassing the immune system [16, 17] making harder the development of efficient drugs in the fight against them. Furthermore, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) such as nucleic acids, glycoproteins, lipoproteins but also other small molecules that can be found in the structural components of the virus, can lead to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines that in turn they activate transcription factors and the JAK–STAT pathways leading to a further activation and release of other cytokines such as the IL-1β, IL-6, interferon (IFN)-γ, IFN-α, TNFα, and other cytokines and chemokines. In this direction, a cascade of several cytokines has been described in more serious cases of COVID-19, that is characterised by high titers of the IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, TNFα and chemokines [11, 18, 19] (Fig. 1). Some of these cytokines such as the TNFα, IL-1, and IL-6 get neutralized by the respective inhibitors, drugs that are given in rheumatologic patients as part of their treatment and this is why they can be used in patients with COVID-19. The specific implication of one another can be used to achieve the best results. Unfortunately, at the moment, we do not have a standardized equipment to support it and it can be said that it constitutes an unmet need.

Fig. 1.

Immunological response to SARS-CoV-2. While the virus is self-replicating in the alveolar cells (1), it also damages it and this will initiate the inflammatory response. Injured alveolar cells release interferons, cytokines as well as its intracellular components (2). Interferons α, β act in a paracrine manner and have numerous effects on the surrounding cells preparing them for the ongoing infection. The primary function is to induce protection against viruses in neighbouring non-infected cells (3). Alveolar macrophages detect cell injury via damage associated molecular patterns from the alveolar cells (4). They also respond to the cytokines released by injured alveolar cells. This causes the alveolar macrophages themselves to secrete cytokines such as TNFα, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, as well as other chemokines (5). The inflammatory process occurring within the lung parenchyma stimulates nerve endings responsible for initiating the cough reflex. Thus, people often present with a dry cough early on. TNFα and IL-1β are pro-inflammatory cytokines and cause increased vascular permeability and increase in expression of adhesion molecules. This allows recruitment of more immune cells including neutrophils and monocytes. The alveolar macrophage can also detect the virus (6) using its special receptors called Toll-like receptors (TLRs). It can engulf the virus particles to phagocytosis, process it, and then present it on its surface (7). Studies have shown that the viral proteins can be presented. By presenting the viral proteins, specific T-cells may recognise them and mount an adaptive immune response (8) consisting of T-cell activation and production of a plethora of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that may lead to a cytokine storm. In addition, B-cells or the plasma cells will then be activated and produce antibodies against the viral proteins (9)

Patients with IA have a well-known increased risk of infections in comparison with the general population [20]. This could be the result of their ailment in sine (high disease activity means augmented risk of infections) [21], their pharmacologic treatment, but also their comorbidities were present [22]. Regarding the pharmacologic treatment of the inflammatory arthritides, GCs and the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the most widely used. These drugs inhibit the physiologic inflammatory response and thus increase the likelihood of an infection [23, 24]. MTX does not seem to have an increased risk for infections except if it is used in combination with GCs [25]. On the other hand, and in contrast to MTX, bDMARDs have been proved to be responsible for increased risk for infections and it seems to be in proportion to patient’s age but also the co-administration of GCs in doses over 7.5 mg/day [26]. It is also known that TNFα inhibitors are correlated with higher rates of infection. Surprisingly, in our study, this has not been shown and our patients did not develop a severe form of COVID-19. A possible explanation is that TNFα is involved in the formation of the cytokine storm and its inhibition may be helpful in this direction leading to a “milder” form of the COVID-19 [5–7]. According to bibliographic data, TNFα inhibitors such as etanercept, adalimumab, certolizumab-pegol and infliximab do not have significant differences in response to COVID-19 in comparison with those of the general population. It has been reported that the TNFα exists both in the serum and the tissues of patients with COVID-19 [27]. Furthermore, it has been postulated that administration of TNFα inhibitors could end up in an indirect tying down of the IL-6. This possibility comes after in vitro studies demonstrating that IL-6 and TNFα have been regulated from the recombinant protein S of SARS-CoV 2002 indicating that TNFα inhibitors or the IL-6 inhibitors could possibly decrease the cytokine storm seen in COVID-19 patients [28]. Other clinical trials have been carried out to explore the possible role of other IL inhibitors such as the IL-6 and IL-1β in severe cases of COVID-19 [29–32]. The JAK-STAT pathway inhibitors are also inhibiting indirectly the IL-6 and are a matter of intense research [33, 34]. To fully evaluate the use of other cytokines that are responsible for the induction of the cytokine storm in COVID-19 patients more research is needed. In this direction, it could be postulated that other biologics may help in the combat of COVID-19 or its complications. On the other hand, different kind of infections are a concern when using these medicines as they can incur in COVID-19 flares [35, 36]. Thus, failure to regulate these cytokines is interesting not only for the rheumatic patients but also those with COVID-19 [37–39]. Although there is a multitude of medicines in research for the treatment of COVID-19, until the day that this manuscript is written, treatment is only supportive [40].

IAs do not seem to be a risk factor for a severe form of COVID-19 despite the immunosuppressive drugs. In the meantime, studies are not yet sufficient to reach to safe conclusions for this topic [41].

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected significantly the management of rheumatic diseases. On one hand, the use of cs and bDMARDs which pose an increased risk for infections in general, and on the other hand, the difficulty in achieving remission or low disease activity. Based on the data presented from our patients in a rheumatology setting being treated with csDMARDs and/or bDMARDs and are on remission or low disease activity, these patients have about the same symptoms as those from the general populations. In addition, from the small sample of patients tested for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies after the infection, it seems that they achieve a good immunologic response even 6 months after the primary infection. This means that even in rheumatologic patients that are in an immunocompromised state either due to their treatment, an effective and sustained immune response can be achieved after their exposure to the virus. On the other hand, we cannot know precisely that exact length of the time that they may have an efficient immune response if they ever come in contact again with the same virus.

Thus, patients suffering from IA should carry on with their treatment even amidst the COVID pandemic as their medication seems to mitigate the course of the SARS-CoV-2 infection, and gives them the chance to have a milder course of this particular infection.

Author contributions

All authors have contributed equally and take full responsibility for all aspects of the work and the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Michalis P. Migkos, Email: michalis.migkos@yahoo.gr

Evripidis Kaltsonoudis, Email: eurkaltsonoudis@hotmail.com.

Eleftherios Pelechas, Email: pelechas@doctors.org.uk.

Vassiliki Drossou, Email: drossou.v@gmail.com.

Panagiota G. Karagianni, Email: karagiannigiota82@gmail.com

Athanasios Kavvadias, Email: akavvadiasgi@gmail.com.

Paraskevi V. Voulgari, Email: pvoulgar@uoi.gr

Alexandros A. Drosos, Email: adrosos@uoi.gr, http://www.rheumatology.gr

References

- 1.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/50140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang T, Du Z, Zhu F, Cao Z, An Y, Gao Y, et al. Comorbidities and multi-organ injuries in the treatment of COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10228):e52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30558-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sepriano A, Kerschbaumer A, Smolen JS, van der Heijde D, Dougados M, van Vollenhoven R, et al. Safety of synthetic and biological DMARDs: a systematic literature review informing the 2019 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(6):760–770. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hyrich KL, Machado PM. Rheumatic disease and COVID-19: epidemiology and outcomes. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2021;17(2):71–72. doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-00562-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gianfrancesco M, Hyrich KL, Al-Adely S, Carmona L, Danila MI, Gossec L, et al. Characteristics associated with hospitalization for COVID-19 in people with rheumatic disease: data from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance physician-reported registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:859–866. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haberman RH, Castillo R, Chen A, Yan D, Ramirez D, Sekar V, et al. COVID-19 in patients with inflammatory arthritis: a prospective study on the effects of comorbidities and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs on clinical outcomes. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72:1981–1989. doi: 10.1002/art.41456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monti S, Balduzzi S, Delvino P, Bellis E, Quadrelli VS, Montecucco C. Clinical course of COVID-19 in a series of patients with chronic arthritis treated with immunosuppressive targeted therapies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:667–668. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ, et al. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winthrop KL, Mariette X. To immunosuppress: whom, when and how? That is the question with COVID-19. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(9):1129–1131. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferro R, Elefante E, Baldini C, Bartoloni E, Puxeddu I, Talarico R, et al. COVID-19: the new challenge for rheumatologists. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020;38:175–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pelechas E, Drossou V, Voulgari PV, Drosos AA. Anti-rheumatic drugs for the fight against the novel coronavirus infection (SARS-CoV-2): what is the evidence? Mediterr J Rheumatol. 2020;31(Suppl 2):259–267. doi: 10.31138/mjr.31.3.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization (2020) Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infection is suspected: interim guidance. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/clinical-management-of-covid-19. Accessed 10 Jan 2021.

- 13.Zou Z, Yan Y, Shu Y, Gao R, Sun Y, Li X, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from lethal avian influenza a H5N1 infections. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3594. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabi FA, Al Zoubi MS, Kasasbeh GA, Salameh DM, Al-Nasser AD. SARS-CoV-2 and coronavirus disease 2019: what we know so far. Pathogens. 2020;9:231. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9030231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li X, Geng M, Peng Y, Meng L, Lu S. Molecular immune pathogenesis and diagnosis of COVID-19. J Pharm Anal. 2020;10:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Totura AL, Baric RS. SARS coronavirus pathogenesis: host innate immune responses and viral antagonism of interferon. Curr Opin Virol. 2012;2:264–275. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Astuti I, Ysrafil Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): an overview of viral structure and host response. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:407–412. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wan S, Yi Q, Fan S, Lv J, Zhang X, Guo L, et al. Characteristics of lymphocyte subsets and cytokines in peripheral blood of 123 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (NCP) Medrxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.10.20021832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tisoncik JR, Korth MJ, Simmons CP, Farrar J, Martin TR, Katze MG. Into the eye of the cytokine storm. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev Membr. 2012;76:16–32. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.05015-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franklin J, Lunt M, Bunn D, Symmons DPM, Silman AJ. Risk and predictors of infection leading to hospitalisation in a large primary-care-derived cohort of patients with inflammatory polyarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:308–312. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.057265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Accortt NA, Lesperance T, Liu M, Rebello S, Trivedi M, Li Y, et al. Impact of sustained remission on the risk of serious infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2018;70:679–684. doi: 10.1002/acr.23426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dougados M, Soubrier M, Antunez A, Balint P, Balsa A, Buch MH, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities in rheumatoid arthritis and evaluation of their monitoring: results of an international, cross-sectional study (COMORA) Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;73:62–68. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Listing J, Gerhold K, Zink A. The risk of infections associated with rheumatoid arthritis, with its comorbidity and treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;52(53–61):29. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turesson C. Comorbidity in rheumatoid arthritis. Swiss Med Wkly. 2016;146:w14290. doi: 10.4414/smw2016.14290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smitten AL, Choi HK, Hochberg MC, Suissa S, Simon TA, Testa MA, Chan KA. The risk of hospitalized infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:387–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan Y, Zou Z, Sun Y, Li X, Xu KF, Wei Y, Jin N, Jiang C. Anti-malaria drug chloroquine is highly effective in treating avian influenza A H5N1 virus infection in an animal model. Cell Res. 2013;23:300–302. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang L, He W, Yu X, Hu D, Bao M, Liu H. Coronavirus disease 2019 in elderly patients: characteristics and prognostic factors based on 4-week follow-up. J Infect. 2020;80:639–645. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang W, Ye L, Ye L, Li B, Gao B, Zeng Y. Up-regulation of IL-6 and TNF-alpha induced by SARS-coronavirus spike protein in murine macrophages via NF-kappaB pathway. Virus Res. 2007;128:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tocilizumab to prevent clinical decompensation in hospitalized, non-critically Ill patients with COVID-19 pneumonitis. https://www.ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04331795. Accessed 10 Jan 2021

- 30.Efficacy of early administration of Tocilizumab in COVID-19 patients. https://www.ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04346355. Accessed 10 Jan 2021

- 31.A study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Tocilizumab in hospitalized participants with COVID-19 pneumonia. https://www.ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04372186. Accessed 10 Jan 2021

- 32.A study to investigate intravenous Tocilizumab in participants with moderate to severe COVID-19 pneumonia. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04363736. Accessed 10 Jan 2021

- 33.Stebbing J, Phelan A, Griffin I, Tucker C, Oechsle O, Smith D. COVID-19: combining antiviral and anti-inflammatory treatments. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:400–402. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20):30132-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richardson P, Griffin I, Tucker C, Smith D, Oechsle O, Phelan A, et al. Baricitinib as potential treatment for 2019-nCoV acute respiratory disease. Lancet. 2020;20(4):400–402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736:30304-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Listing J, Gerhold K, Zink A. The risk of infections associated with rheumatoid arthritis, with its comorbidity and treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;52:53–61. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galloway JB, Hyrich KL, Mercer LK, Dixon WG, Fu B, Ustianowski AP, et al. AntiTNF therapy is associated with an increased risk of serious infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis especially in the first 6 months of treatment: updated results from the British Society for Rheumatology biologics register with special emphasis on risks in the elderly. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;50:124–131. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qin C, Zhou L, Hu Z, Zhang S, Yang S, Tao Y, et al. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:762–768. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li G, Fan Y, Lai Y, Han T, Li Z, Zhou P, et al. Coronavirus infections and immune responses. J Med Virol. 2020;92:424–432. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu D, Yang XO. TH17 responses in cytokine storm of COVID19: an emerging target of JAK2 inhibitor Fedratinib. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53(3):368–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu C, Zhou Q, Li Y, Garner LV, Watkins SP, Carter LJ, et al. Research and Development on therapeutic agents and vaccines for COVID-19 and related human coronavirus diseases. ACS Cent Sci. 2020;6:315–331. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ouédraogo DD, Joelle W, Tiendrébéogo S, Kaboré F, Ntsiba H. COVID-19, chronic inflammatory rheumatic disease and anti-rheumatic treatments. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;29:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05189.y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.