Abstract

During intestinal infection, microbes induce ROS by various mechanisms in C. elegans. ROS can have beneficial roles, acting as antimicrobials and as signaling molecules that activate cytoprotective pathways. Failure to maintain appropriate levels of ROS causes oxidative stress and cellular damage. This review uses the Damage Response Framework to interpret several recent observations on the relationships between infection, host response, and host damage, with a focus on mechanisms mediated by ROS. We propose a unifying hypothesis that ROS drive a collapse in proteostasis in infected C. elegans, which results in death during unresolved infection. Because the signaling pathways highlighted here are conserved in mammals, the mentioned and future studies can provide new tools of hypothesis generation in human health and disease.

Keywords: Caenorhabditis elegans, model organism, infection, pathogen, bacteria, intestine, epithelium, reactive oxygen species, proteostasis, host defense, Innate immunity, antimicrobial, cytoprotection, autophagy, Transcription, gene induction, DUOX, signaling, damage

Graphical abstract

The Damage Response Framework and host-pathogen interactions in Caenorhabditis elegans

It is generally thought that the immune system’s main function is to discriminate self from non-self, and to eliminate the latter. Non-self includes microbes, pathogenic and nonpathogenic. For an infected animal, the prime imperative is to ensure survival to maximize reproduction (and, thus, transmission of its genes to the next generation). For the infecting microbe, the onus is on reproduction and transmission, as well [1]. This genetic survival dynamic is not necessarily antagonistic, but in case it is, the host must be prepared to fight back. To describe the complex and dynamic relationships among infection, host response, and host damage, Casadevall and Pirofsky developed the Damage Response Framework (DRF) [2]. A central tenet of the DRF is that damage to the host, rather than microbe-derived molecules alone, is a key signal of infection that triggers the host defense response in its components cell-autonomous (e.g. antimicrobial peptides, cytoprotection, repair) and systemic (e.g. hormones, cytokines, antibodies). Disease is the accumulation of damage above a certain threshold that is determined in each individual by several factors (Fig. 1A). Infections cause disease according to the amount of damage to the host, which can be caused by the pathogen directly or indirectly, through the host response that they elicit [2]. To fully understand infectious disease, it is important to elucidate the direct mechanisms of host damage by the pathogen and the mechanisms of self-inflicted damage.

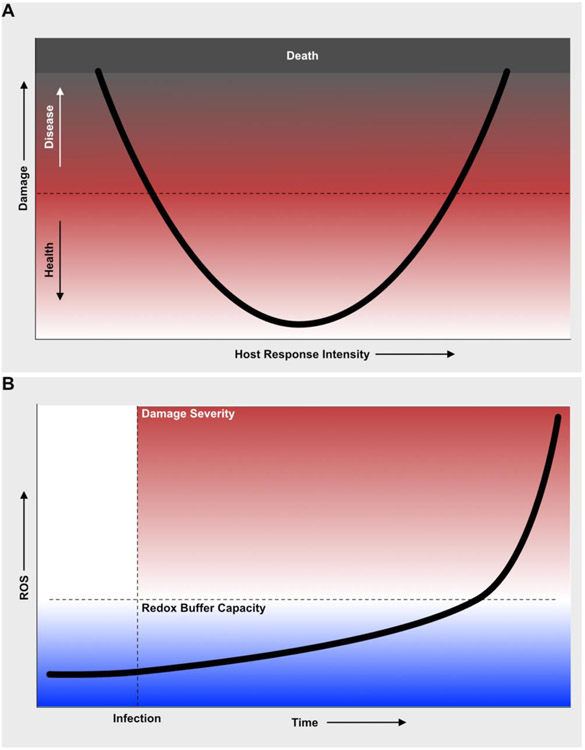

Figure 1. The Damage Response Framework and theoretical role of ROS during infection in C. elegans. A. The damage response framework to interpret the effects of mutations and treatments on C. elegans – pathogen interactions.

The black curve represents the trajectory of the physiological state of the host during infection. If the host response is too weak (on the left), the physiological state trends to disease because of damage to the host caused by the pathogen. If the host response is too strong (right), the physiological state trends to disease because of immunopathology. Perfect matching of the host response to the infection results in optimal health (center). B. Theoretical role of ROS as main drivers of host damage and pathogenesis. Infection induces the early production of ROS. In the unresolving infection experimental setup, as time passes ROS accumulate as a result of both host response and damage. ROS accumulation is buffered by the redox buffering system within the host’s cells. When this capacity is exceeded, ROS accumulate rapidly, leading to rapidly accumulating host damage and functional decay.

Over the past two decades, C. elegans has served as a model organism to study host-pathogen interactions. This review will focus on bacteria that infect C. elegans by the physiologically relevant oral route and involve the intestinal epithelium (Text Box 1) [3] [4] [5]. C. elegans can sense intestinal infection and defend against it by expressing antimicrobials [6]. Under the most common experimental conditions, infection is continuous and the main endpoint, death [4]. Despite major advances in several directions, the mechanisms by which intestinal infections cause nematode death are not well understood. Moreover, a wealth of experimental data support a central role of reactive oxygen species (ROS), proteostasis, and cellular defense mechanisms in host survival of diverse intestinal infections, but precisely how these processes are integrated at an organismal level and contribute to host defense is not known. In this review, we submit that experimental evidence on C. elegans-pathogen interactions is consistent with the DRF, and put forth that ROS production may be a key early and unifying event that elicits host defense early in the infection and later drives organismal failure and death (Fig. 2).

Text Box 1: Hallmarks of intestinal pathogenesis in C. elegans.

Mitochondrial damage

Several Pseudomonas bacteria from the C. elegans natural habitat cause mitochondrial dysfunction, measured by activation of activating transcription Factor associated with stress (ATFS-1/ATF5) and induction of chaperone target gene heat shock protein-6 (hsp-6/HSPA9) [7]. Moreover, human bacterial pathogen P. aeruginosa produces pyoverdine, a siderophore that disrupts C. elegans mitochondria by removal of iron, and activates ATFS-1/ATF5 [8]*. In contrast, avirulent P. aeruginosa mutants that do not produce pyoverdine do not activate ATFS-1/ATF5 [8]*. Additionally, B. thuringiensis causes mitochondrial rounding, indicating mitochondrial damage [9]. Thus, loss of mitochondrial homeostasis or mitochondrial damage appears to be an early event in diverse intestinal infections.

Intestinal destruction

Pioneering work with Bacillus thuringiensis showed drastic changes to intestinal epithelial cells (IECs), which included mitochondrial damage, distension of the intestinal lumen, loss of IEC volume, and shearing of microvilli [9]. Later work showed that the mechanism of such intestinal destruction involved spore crystal proteins, pore-forming cytotoxins [10]. However, how crystal toxins kill C. elegans is not fully understood [10] [11]. It is worth noting that starvation, caused by intestinal malfunction or destruction, is unlikely to cause death in such infections. Adult C. elegans can survive complete removal of food, which in fact results in lifespan extension by dietary restriction [12]. Bacteria that are not readily digested due to a refractory cell wall, large size, or consistency cause similar effects [13] [12].

Somewhat like B. thuringiensis, human pathogen Staphylococcus aureus damages IECs by causing retraction of microvilli, intestinal cell lysis, and death [9] [6]. Despite evidence of membrane-active injury, the molecular mechanisms involved are not known. S. aureus mutants that lack specific pore-forming hemolysins were indistinguishable from wild type both in killing capacity and intestinal destruction [6]. Furthermore, infection with Enterococcus faecalis causes intestinal distension but fails to lyse IECs [14].

In contrast to such Gram-positive bacteria, Gram-negative human pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa does not immediately destroy the intestine, but rather appears to disrupt intracellular membrane trafficking pathways [6]. P. aeruginosa produces a plethora of virulence factors, including pyoverdine and phenazines, which disrupt respiration, and exotoxin A (ToxA), which inhibits translation [15][16][17][18]. Pyoverdine and phenazines are toxic to C. elegans [8]* [15][16]. Although they elicit ROS, mitochondrial stress, iron deprivation [8]*, and autophagy [19], the precise mechanism of nematode killing has not been elucidated.

ToxA and Cycloheximide induce the transcription of overlapping sets of C. elegans genes, indicating that translation is somehow monitored for infection surveillance [18][17]. Whether this occurs within the intestine or in other tissues is not known. Moreover, deletion of toxA did not affect P. aeruginosa virulence towards C. elegans, implying that the mechanism of nematode killing does not require ToxA and that the host response elicited by ToxA cannot mitigate such mechanism [18].

Studies such as these examples revealed that damage to the intestinal epithelium is a visible hallmark of intestinal infections in C. elegans, as it is in mammals. The relationship between such morphological manifestations of pathogenesis and the recently identified pathway of infection sensing through distention of the intestinal lumen is not clear [20]**. What is clear is that the intestinal epithelium is at once a major site of antimicrobial peptide production [21]* and of nutrient absorption [22]. Therefore, disruption of the epithelial barrier carries severe consequences for organismal metabolism.

Nutritional deficiency

In the laboratory, infection of C. elegans is usually performed by removing the animals from solid or liquid cultures of nonpathogenic Escherichia coli and placing them in solid or liquid cultures of pathogenic bacteria [3] [4]. Therefore, in addition to infectious injury, the nematodes experience changes in the nutritional content of the bacteria that they ingest. Inevitably, this means that physiological, behavioral, and gene expression changes observed during infection are likely the result of host responses to combined stresses, including infection and nutritional change. However, the same can be said about intestinal host defense responses in mice or humans [23].

In the wild, C. elegans encounter microbial communities of widely variable composition and, presumably, nutritional value [7]. Therefore, it is highly likely that the host response to infection and metabolic adaptation to nutritional challenge evolved to be tightly coupled. Nonetheless, an investigator may wish to focus on non-metabolic aspects of host defense. Methods are deployed to control for nutritional differences between the reference nonpathogenic E. coli and pathogens (e.g. use of avirulent pathogen mutants [24] and phylogenetically related avirulent species [25]). However, these approaches do not completely eliminate nutritional change as a contributing factor.

On top of changes in the nutritional quality of the food, infected C. elegans experience degradation of the intestinal epithelium, as mentioned above [4]. Because IECs are essential for nutrient absorption, pathogenesis itself is inextricably linked to nutritional challenge, which impacts host physiology in many ways. Consequently, innate immunity and metabolism are tightly coupled in C. elegans, as they are in mammalian gastrointestinal infections [26].

Metabolic changes are apparent in infected C. elegans, and in some cases these have been linked to specific transcriptional responses. For example, P. aeruginosa caused rapid loss of somatic lipids, which was due to hyperactivation of stress-response transcription factor skinhead/ nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor-2 (SKN-1/NRF2) [27]*; similar independent studies failed to identify somatic lipid loss, but the reasons for such discrepancy are not immediately obvious [28]. Transcription factor abnormal dauer formation- 16/ forkhead box 3(DAF-16/FOXO3) becomes activated during starvation, oxidative stress, and heat shock [29]. Consistent with the stresses caused by infection, E. faecalis causes DAF-16/FOXO3 activation [25]. Despite its ability to induce mitochondrial stress, ROS, and nutritional deficiency, P. aeruginosa does not activate DAF-16/FOXO3 [29], which is due to the induction of insulin signaling in C. elegans by the pathogen [29]. Like P. aeruginosa, E. faecalis causes somatic lipid loss, but the signaling pathway involved is unknown. Under starvation, nuclear hormone receptor-49/hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 (NHR-49/HNF4) activates lipid catabolism genes, presumably to support reproduction [30]. However, transcription factor NHR-49/HNF4 was required for gene induction during infection [28].

Therefore, the combination of mitochondrial damage, intestinal destruction, and nutritional challenge likely results in a precipitous drop in intracellular energy equivalents (i.e. ATP) during intestinal infections. Consistent with this hypothesis, such infections induce catabolism through various molecular mechanisms that are only partially understood, as discussed. In addition to such depletion of energy stores, several mechanisms unleashed during intestinal infections (such as mitochondrial damage) drive the generation of a host defense double-edged sword: reactive oxygen species.

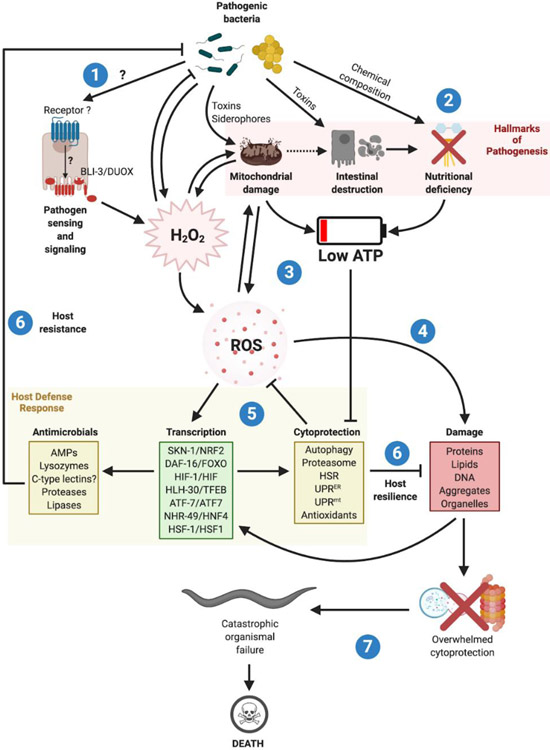

Figure 2. Centrality of ROS as triggers of host defense responses and as drivers of bacterial pathogenesis in C. elegans.

(1) Pathogenic bacteria infecting the intestine are sensed by chemosensory neurons through bacterial secondary metabolites [94], by mechanosensory neurons that sense gut distention [20]**, or by hypothesized pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) in sentinel tissues. Both the nervous system and PRR mechanisms of detection, the “early warning system”, activate immune effector proteins through stress-responsive signal transduction pathways, most prominently mediated by p38 MAPK, JNK, AMPK/mTORC1, TGF-β, and insulin [95]. BLI-3/DUOX becomes activated by an unknown mechanism, producing H2O2. In addition to antimicrobial activity, BLI-3/DUOX can damage cellular structures and organelles in a concentration-dependent manner. Damage to the mitochondria, through ROS or directly by the pathogen, increases H2O2 and ROS concentrations in a positive feedback loop. Furthermore, some pathogens produce ROS under stress, thereby directly triggering defense responses and host damage. (2) In addition to mitochondria, intestinal pathogens damage the epithelium and cause metabolic stress (the Hallmarks of Pathogenesis). (3) Organellar damage, intestinal destruction, and metabolic stress compound to increase ROS concentrations and deplete cellular ATP. (4) While high ROS concentrations cause damage to biomolecules and organelles, proteostasis is further disrupted by ATP depletion. ATP depletion impairs chaperones, proteasomes, and autophagy mechanisms, exacerbating the loss of homeostasis. (5) While ATP depletion engages metabolic homeostasis mechanisms, such as lipid catabolism (not shown), ROS activates several cytoprotective mechanisms via stress-responsive pathways and activation of stress-response transcription factors with partially overlapping functions. These transcription factors are key for the activation of cytoprotective antioxidants, autophagy, proteasomes, and chaperones. (6) Collectively, these host defense mechanisms function to counteract ROS and ATP depletion, by inducing metabolic adaptations, enhancing protein folding, and activating cellular clearance. These restorative functions are known as mechanisms of host infection resilience [70][81]. In addition to resilience mechanisms, the same pathways and transcription factors induce expression of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), lysozymes, secreted proteases and lipases, and potentially antimicrobial C-type lectins. These mechanisms, which function to reduce pathogen load and clear the infection, are known as mechanisms of host infection resistance. (7) Given the chance, C. elegans learn to avoid pathogenic bacteria and can reach sexual maturity before death [96]. Under experimental conditions, this is prevented and the non-resolving infection causes damage to accumulate to the point where the cytoprotective mechanisms become overwhelmed. At this tipping point, the cells begin to malfunction and die (possibly through necrosis [85]), resulting in catastrophic organismal failure. Exactly which cells must die for the organism to perish is not known, but it is possible that neuronal death is an early precipitating event [97]. AMPs, antimicrobials. HSR, heat shock response.

Reactive oxygen species

Chemical reactions that cause incomplete reduction of molecular oxygen, O2, generate the reactive oxygen species (ROS) H2O2, O, and O2.−, and subsequent reactions create hypohalous acids and organic peroxides [31]. Throughout the Tree of Life, ROS function as host defense mechanisms and as signaling molecules, while also harboring great potential for host damage [31]. C. elegans is no exception. In the formerly favored Oxidative Theory of Aging, ROS were mainly thought to drive oxidative damage and aging [32]. Starting with the first evidence that bacterial infections induce ROS in C. elegans [33], a more complex picture emerged, where infected C. elegans initiate ROS production to kill the pathogen and to induce defense responses (Fig. 2) [34]**. If persistent or continuous infections drive chronically high ROS production, exceeding the redox buffering capacity of the organism’s cells, oxidative damage to host biomolecules may drive pathology and even death (Fig. 1B). Similar mechanisms have been described in mammalian infections [35] [36].

ROS production

Although infections by pathogens induce ROS in C. elegans, it can be difficult to define the source and mechanism of production. Known examples demonstrate how ROS can be produced by the host, as part of the antimicrobial defense response or because of cellular damage, or by the pathogen.

By the host

The first report of ROS generated in the C. elegans intestine upon E. faecalis infection showed that ROS are important in host defense [33]. This pioneering study suggested that blistered cuticle-3/dual oxidase (BLI-3/DUOX1) is the only functional NADPH oxidase/dual oxidase (NOX/DUOX) enzyme in C. elegans and is the main source of ROS during infection [24]. Using a reporter yeast strain expressing YEGFP from the promoter of catalase A (CTA1) and an innovative H2O2 detection assay, subsequent work confirmed that BLI-3/DUOX generates ROS in the intestine during infection with E. faecalis and Candida albicans [37]. Additionally, mutants lacking BLI-3/DUOX were hypersusceptible to E. faecalis infection [34]**. Independent work showed that PBOc defective/calcineurin-like EF-hand protein 1 (pbo-1/CHP1) mutant C. elegans were defective in H2O2 generation during E. faecalis infection, due to dysregulated intestinal lumen pH [31]. Consistent with the protective roles of ROS, pbo-1/CHP1 mutants were hypersusceptible to E. faecalis-triggered nematode death [31]. Whether BLI-3/DUOX is activated by all infections, and whether ROS thus generated protect the host against all pathogenic intestinal bacteria, remains a key knowledge gap.

By damage to the host

Damaged mitochondria are a major source of ROS production during infection. For example, P. aeruginosa pyoverdine induces mitochondrial damage, increasing ROS generation [15]. mtROS generated due to low rates of respiration and possibly infections activate hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) [38]. HIF-1/HIF1 activation results in higher levels of cytosolic ROS possibly due to downregulation of iron homeostasis genes, forming a positive feedback loop.

By the pathogen

Some bacteria generate ROS as a virulence mechanism. For example, Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Strep) kills C. elegans within minutes of infection [39]. Experiments using catalase and exotoxins (slo, spe-b) S. pyogenes mutants revealed that H2O2 was necessary and sufficient for nematode killing [39]. Moreover, the time required for killing was indirectly proportional to the H2O2 concentration measured in the solid infection media. Therefore, certain pathogenic bacteria use ROS to their advantage; whether the endogenous microbiota of C. elegans also produce ROS to modulate host defense is not known.

ROS and damage

ROS can damage proteins and disrupt mitochondria in C. elegans [40] [41] [42]. For example, ROS can oxidize cysteine residues and generate carbonyl residues from many amino acid moieties, rendering proteins dysfunctional [43] [40]. ROS cause oxidation of amino acid side chains such as reactive cysteines, resulting in ectopic protein cross linkages, misfolding, and aggregation, as shown using fluorescently-tagged aggregation-prone poly-Gln proteins [44][45]. Moreover, ROS generated during infection can drive pathogenesis. For example, metabolites from Streptomyces venezuelae induce ROS, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction as shown by induction of mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) chaperone hsp-6 [46]. In addition, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium drives ROS generation throughout the nematode body [47]. Moreover, inhibition of ROS with Ascorbic acid prevented nematode death [47].

Endogenous ROS generation was dependent on Salmonella thioredoxin gene trxA, and S. enterica lacking trxA killed slower compared to wild type Salmonella.

ROS as signals

ROS can activate C. elegans signaling pathways and transcription factors that mitigate infection, induce expression of enzymes that detoxify ROS, and help the organism adapt to metabolic changes. Transcription factor DAF-16/FOXO3 is repressed by insulin signaling and translocates into the nucleus, where it drives expression of a broad stress response that includes metabolic, proteostatic, and antioxidant genes (Fig. 3) [25] [36]ROS oxidize Transportin-1 (TNPO1), which allows it to covalently bind DAF-16/FOXO3, resulting in its nuclear translocation [48]. Moreover, mutations that disrupt insulin signaling activate DAF-16/FOXO3 and confer resistance to S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and E. faecalis [33] [44]. Consistent with a role for ROS in DAF-16/FOXO3 regulation during infection, E. faecalis has been shown to both induce ROS (through BLI-3/DUOX) and activate DAF-16/FOXO3 [33]. Whether other bacteria that colonize the intestine also trigger ROS and DAF-16/FOXO3 remains to be determined.

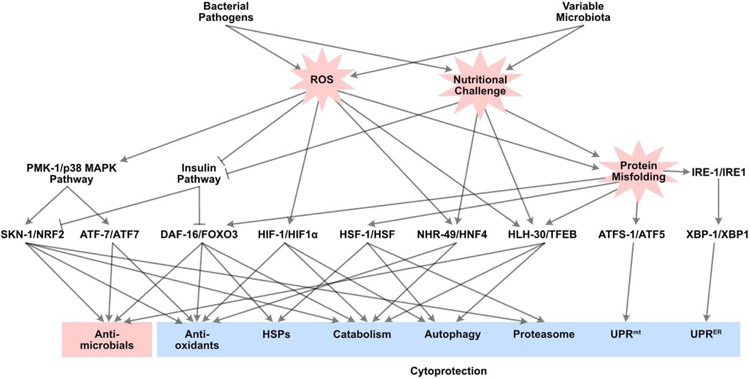

Figure 3. Diagram of the major intestinal host defense pathways identified in C. elegans.

Overall conceptual organization of the transcriptional host response to infection in C. elegans. Bacterial pathogens and microbiota components cause ROS production and nutritional challenge. These twin stresses drive protein misfolding, which in turn drives pathology. ROS sensing leads to activation of the p38 MAPK pathway and inhibition of the insulin pathway, which results in activation of transcription factors SKN-1/NRF2, ATF-7/ATF7, and DAF-16/FOXO3. In addition, ROS activate HIF-1/HIF1α, NHR-49/HNF4, and HLH-30/TFEB. Nutritional challenges, including starvation, also activate NHR-49/HNF4 and HLH-30/TFEB. Protein misfolding and proteostasis loss activate DAF-16/FOXO3, HSF-1/HSF, HLH-30/TFEB, ATFS-1/ATF5, XBP-1/XBP1, and IRE-1/IRE1. Jointly, these transcriptional regulators orchestrate the complex host response to infection in a dynamic fashion. The host response comprises antimicrobial elements, which promote infection clearance, and cytoprotective elements, which promote host resilience. For simplicity, arrows linking transcription factors to each other (e.g. NHR-49 and HLH-30, IRE-1 and SKN-1) are omitted.

ROS generated in the intestine during E. faecalis and P. aeruginosa infections also activate the p38 MAPK pathway (Fig. 3), causing nuclear translocation of transcription factor SKN-1/NRF2 [50]. Oxidative stress and P. aeruginosa induce overlapping transcriptional responses that require SKN-1/NRF2, further supporting the idea that ROS function as a signal during these infections [40] [50] [51]. The p38 MAPK pathway is also involved in activation of transcription factor ATF (cAMP-dependent transcription factor) family (ATF-7/ATF7), among whose target genes are X-box Binding Protein homolog (xbp-1/XBP1) (involved in the ER unfolded protein response, or UPRER), LC3, GABARAP and GATE-16 family (lgg-1/MAP1LC3) (autophagy), and mtl-1/Metallothionin-1 (oxidative stress response) [18][52]. Thus, ROS activate a broad response mediated by the p38 MAPK pathway that bifurcates at the level of transcription factor regulation (Fig. 3).

In addition, lesser understood mechanisms contribute to the response to ROS in C. elegans. Mitochondrial ROS (mtROS), generated due to low rates of respiration or to infections, activate AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a cellular energy sensor that regulates metabolism and autophagy, by an unknown mechanism [38]. Similarly, mtROS induce hypoxia inducible factor HIF-1/HIF1α (Fig. 3) [38][53]. Since mtROS promote resistance to pathogenic E. coli in a HIF-1/HIF1α- and AMPK-dependent manner, these two regulators may be functionally linked [38].

More recently, helix loop helix-30/Transcription factor EB (HLH-30/TFEB) was identified as a key transcription factor in the host response to S. aureus [54] and B. thuringiensis Crystal toxin [55]. Although the regulation of Helix loop helix-30/Transcription factor EB (HLH-30/TFEB) during infection is not well understood, it is also activated by ROS and heat shock (Fig. 3) [56]*. Moreover, nutritional stress and hypoxia induce the expression of HIF-1/HIF1α-dependent gene flavin containing monooxygenase-2 (fmo-2/FMO5) in a partially HLH-30/TFEB-dependent manner, suggesting that these two transcription factors may functionally interact during infection [57].

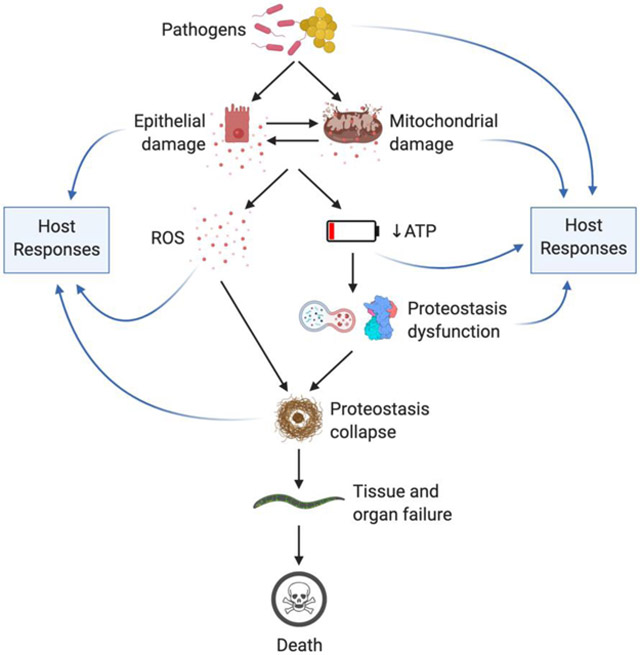

Proteostasis collapse

In infected C. elegans, the twin insults of ROS induction and ATP depletion (Text Box 1) may cause the accumulation of damage to cellular structures, while the proteostatic network (including autophagy, proteasomes, and chaperones [58]) lacks the energy to prevent collapse (Fig. 2). Infections with S. aureus, E. faecalis, P. aeruginosa, or S. enterica cause aggregation of fluorescently-tagged poly-Gln proteins in the intestinal epithelium [59]. Antioxidant compounds prevent such protein aggregation during infection [59], consistent with ROS being major drivers of proteostasis collapse under these conditions.

In addition to their direct effects on protein oxidation, ROS cause damage to mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum [40]. The resulting depletion of ATP and disruption of protein folding may compound the loss of proteostasis caused by protein oxidation and aggregation (Fig. 2) [60]. Over the course of chronic or continuous infections, the accumulation of damaged proteins and organelles may overwhelm the proteostasis network, which requires ATP to restore homeostasis [61]. However, the organismic connection between loss of proteostasis and death is unclear. It is possible that specific cells or tissues are particularly sensitive and die earlier during pathogenesis. Although the relevant C. elegans tissues most affected by proteostasis collapse have not been elucidated, evidence suggests that neurons are highly susceptible to early damage by ROS [62]. Loss of neuronal activity in the early stages of infection could explain the oft-cited phenotype of motility loss in diverse infection models [63][24].

Whatever the actual sequence of tissue death, C. elegans possess several mechanisms to detect and repair cellular damage. Many of these mechanisms detect ROS, possibly as an anticipatory signal for the ensuing debacle.

Cytoprotective host responses to ROS and protein aggregation

Understanding of cytoprotective defenses deployed by C. elegans during infection largely derives from work that focused on specific abiotic stressors, such as oxidative stress, heat shock, intoxication of mitochondria and ER, and cellular clearance mechanisms induced by protein misfolding. Aided by mutations in specific pathway components and by the advent of transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic technologies, researchers in the C. elegans host defense field were able to identify the biological relevance of these cytoprotective mechanisms to bacterial pathogenesis. As predicted by the DRF, multiple host mechanisms evolved for counterbalancing the detrimental effects of bacterial infections.

Antioxidants

Genes that encode antioxidant proteins, such as glutathione S-transferases, superoxide dismutases, and flavin-containing monooxygenases are often upregulated during infection [64][28][65]. As mentioned above, SKN-1/NRF2 and DAF-16/FOXO3 have emerged as major transcriptional inducers of the antioxidant response (Fig. 3). In addition, transcription factor NHR-49/HNF4 was recently implicated in the host response to oxidative stress, when it drives the expression of glutathione S-transferase gst-4 and several other detoxification genes [66]. Recent work also showed that E. faecalis induces a proposed detoxification enzyme encoded by fmo-2/FMO5 through NHR-49/HNF4 [28]. These results are consistent with the idea that E. faecalis, and possibly other pathogens, induce ROS production by C. elegans, and these drive transcriptional responses to limit ROS concentration.

Heat shock response

Genes that encode chaperone proteins that use ATP to catalyze protein folding are induced by the heat shock response via heat shock factor HSF-1/HSF (Fig. 3) [67]. Similar to abiotic heat shock, P. aeruginosa infection causes expression of chaperone genes, such as hsp-90/HSP90 in an HSF-1/HSF1-dependent manner [68]. Furthermore, animals lacking HSF-1/HSF1 are hypersusceptible to various pathogens, including P. aeruginosa and E. faecalis, presumably due to exaggerated protein aggregation [59][68] [69]. HSF-1/HSF1 overexpression and induction by heat shock upregulates expression of autophagy genes, including autophagy-18/WD repeat domain, phosphoinositide interacting 2 (atg-18/WIPI2), as well as autophagosome formation [56]*. This further facilitates removal of protein aggregates [56]*. Although this is a potentially important mechanism of HSF-1/HSF1-mediated cytoprotection during infection (Fig. 3), this has yet to be tested directly.

Organellar unfolded protein response

Disruption of proteostasis within the mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum causes induction of the mitochondrial and ER unfolded protein responses (UPRmt and UPRER, respectively) [70] [71]. The UPRmt is controlled by ATFS-1/ATF5 (Fig. 3), which under homeostatic conditions translocates into mitochondria to be degraded [72]. Damaged mitochondria, unable to import ATFS-1/ATF5, cause ATFS-1/ATF5 to translocate into the nucleus and induce genes that boost mitochondrial homeostasis, such as chaperones (e.g. hsp-6) and mitochondrial protein importers [e.g. Translocase of Outer Mitochondrial Membrane (tomm-20)], as well as ROS detoxification enzymes and antimicrobial genes (e.g. lysozyme lys-2) [70]. Loss of ATFS-1/ATF5 causes hypersusceptibility to P. aeruginosa infection, consistent with the idea that the UPRmt is important to counteract infection-induced mitochondrial dysfunction [73].

The UPRER also responds to ROS during infection. The UPRER is mediated by IRE1 kinase related (IRE-1/IRE1), an ER transmembrane protein that senses ER stress and activates XBP-1/XBP1, which induces the expression of genes to promote ER protein homeostasis [74] (Fig. 3). P. aeruginosa infection activates the IRE-1/XBP-1 axis of the UPRER in a p38 MAPK-dependent manner [75]. Moreover, compared to wild type animals, xbp-1/XBP1 mutants are hypersusceptible to P. aeruginosa- induced death and show abnormal ER morphology when infected [75]. A recent study showed that ROS can sulfenylate a cysteine residue in IRE-1/IRE1 [76]. Sulfenylated IRE-1/IRE1 causes SKN-1/NRF2 activation via the p38 MAPK pathway [76].

Because IRE-1/IRE1 sulfenylation inhibits XBP-1/XBP1, this is thought to be a functional switch for ROS sensing to induce detoxification via SKN-1/NRF2 [76]. It is possible, but not known, that this mechanism is functionally important during infection.

Cellular clearance

Damaged proteins in the cytosol are cleared by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), which adds ubiquitin tags linked at K11, K29, and K48 to proteins destined for proteasomal degradation [77][78]. An E3 ubiquitin ligase composed of Cullin-1 homologs CUL-1 and CUL-6 is transcriptionally upregulated by intestinal infection with cryptosporidium Nematocida parisii [79]. Loss of CUL-1/CUL-6/CUL1, and other UPS genes results in higher pathogen loads, indicating that the UPS is key for host control of cryptosporidium [79]. Whether the UPS plays a key role in control of protein aggregation caused by bacterial pathogens is not known. However, protein aggregation upregulates expression of proteasomal 26S subunit RPT-3/PSMC4 in a SKN-1/NRF2 dependent manner [80]*. Given that SKN1/NRF2 is activated by infection and ROS, it is likely that the UPS plays important roles for cytoprotective host defense in bacterial infections.

Autophagy, broadly defined as a group of mechanisms that mediate cellular breakdown and clearance within specific membrane-bound organelles, plays several key roles in host defense across phylogeny [81]. ROS can induce macroautophagy and mitophagy (the breakdown of large protein aggregates and of damaged mitochondria) by various mechanisms, including transcription factors bZIP transcription factor family-3 (ZIP-3/ATF5) and SKN-1/NRF2, thus preemptively boosting proteostasis [45] [82] [70] [83] [64] [84].

Autophagy is essential for C. elegans defense against various pathogens. For example, LGG-1/LC3 (required for autophagosome formation) mutant animals are hypersusceptible to S. aureus infection compared to WT [54]. Furthermore, P. aeruginosa infection induces autophagy measured by induction of LGG-1/LC3 via extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling [85]. Inhibition of autophagy by knockdown of beclin-1 (BEC-1/BECN1) leads to necrosis and faster killing compared to wild type [85]. In these cases, evidence suggests that these infections are extracellular, supporting a major role for autophagy in clearance of protein aggregates and not of intracellular bacteria in C. elegans. Consistently, mutations in the autophagy pathway cause enhanced susceptibility to a wide range of bacterial pathogens [54].

Alternatively, autophagy may be important for clearance of damaged organelles during infection. As postulated above, early damage to mitochondria by pathogen or ROS may amplify ROS production and protein aggregation (Fig. 2). Damaged mitochondria are unable to import PTEN-induced kinase (PINK-1/PINK1), which causes ubiquitination of mitochondrial outer membrane proteins by E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkinson's Disease Related (PDR-1/Parkin). Ubiquitinated mitochondria recruit autophagosome formation, and are engulfed and degraded by mitophagy [86]. Thus, autophagy may provide cytoprotection by two mechanisms during infection (Fig. 2), by eliminating damaged mitochondria that drive ROS production and ATP depletion, and by clearing protein aggregates.

HLH-30/TFEB is an evolutionarily-conserved master transcriptional inducer of autophagy (Fig. 3) [87]. In addition to infection with S. aureus [54] and B. thuringiensis Crystal toxin [55], heat shock and starvation drive HLH-30/TFEB nuclear translocation [57] [60]. Although a common feature shared by these conditions is the generation of ROS, whether ROS are important for HLH-30/TFEB activation during infection is not known.

Concluding remarks

We have outlined broad strokes of the potential sequence of events that occur when the C. elegans intestine is infected with bacterial pathogens (Fig. 2). We propose that ROS generated during infection precipitate a sequence of injuries and responses that ultimately end in nematode death. During infection, C. elegans suffer pathogen- and self- induced damage. In response, C. elegans upregulate antimicrobials and cytoprotective responses that promote survival [88]. In the experimental setup of continuous infection with highly pathogenic bacteria, both infection and damage linger unresolved. In the various infection models that have been developed, the extent to which ROS mediate host defense or cause host damage may be highly context-specific.

Given the evidence accumulated so far, we propose that ROS and ROS-derived damage are a shared feature among these models, and application of the DRF helps conceptualize the effects of various mutations and chemical treatments on host survival of infections. Mutations and treatments that decrease the amount of ROS, or that enhance the cytoprotective defense mechanisms of antioxidants, chaperones, UPRs, proteasomes, and autophagy generally protect C. elegans against infection-induced death. However, the relevance of each mechanism remains to be examined in each specific pathogen model.

How BLI-3/DUOX is activated upon intestinal infection is unclear, although studies suggest some possible mechanisms. For instance, bacterial-derived uracil functions as an agonist for intestinal DUOX in Drosophila [89]. In C. elegans, infection of the epidermis by fungus Drechmeria coniospora activates BLI-3/DUOX and ROS in a Ca2+-dependent manner [90]. Whether mechanisms also induce BLI-3/DUOX in the intestinal epithelium in C. elegans is not known. Additionally, it is possible that enzymes other than BLI-3/DUOX may contribute to ROS generation under specific conditions.

Multiple studies described pathogen-specific and -shared, or public, transcriptional responses to infection in C. elegans [6][5]. How specificity is achieved, and how the shared responses are regulated, is not well understood. It is possible that ROS drive pathogen-shared responses, but the molecular mechanisms that sense ROS to activate the various signaling pathways involved are mostly unknown. Studies to determine the site and timing of intracellular ROS generation during infection and interaction with the microbiota are crucial for understanding the microbe-specific and -shared components of the transcriptional host response.

The fundamental insights described here are relevant to several aspects of mammalian health and disease. In mammals, ROS generated upon infection in phagocytes and at mucosal surfaces play major roles in innate immune responses [91]. For instance, ROS generated by NADPH oxidase or mitochondria can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, resulting in the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-18 [86] [92]. Furthermore, TLR activation by bacterial ligands induces mtROS for bactericidal killing and for cytokine secretion in mammalian macrophages [93]. Additionally, as in C. elegans, excess ROS leads to disease in vertebrates. Several disorders are aggravated by ROS, including oncogenesis and various cardiovascular, neurological, and fibrotic diseases [60]. Because of the complexity of the systems and the extent of their evolutionary conservation, future studies to unravel the complex and dynamic regulatory networks regulated by and disrupted through ROS induced during infection in C. elegans (Text Box 2), including cell-cell and tissue-tissue communication mechanisms, will likely help understand the beneficial and pathological roles of ROS in human health and disease.

Text Box 2: Key Open Questions.

Which pathogens trigger ROS generation through BLI-3/DUOX?

What pathogenic signals are required for ROS generation in each case?

By which mechanisms does C. elegans sense ROS generated during infection?

How is specificity achieved in the host response to distinct microbes that induce ROS?

What is the relevance of similar ROS-triggered pathways in mammalian host defense?

Highlights.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced through various sources, including mitochondria and DUOX, at sites of infection.

ROS function directly as antimicrobials or indirectly as signals to induce host defense.

Excess ROS damage organelles, such as the mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum, and oxidize host biomolecules.

Consequences of excess ROS include ATP depletion, disruption of metabolism, and loss of proteostasis.

Cytoprotective pathways mitigate ROS-induced damage and counteract organismal failure and death.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Throughout the text, C. elegans names for genes and proteins are given first, followed by their human homologs.

Declarations of interest: none.

References

- 1.Viney ME, Riley EM, Buchanan KL: Optimal immune responses: Immunocompetence revisited. Trends Ecol Evol 2005, 20:665–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casadevall A, Pirofski LA: The damage-response framework of microbial pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2003, 1:17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park HEH, Jung Y, Lee SJV: Survival assays using Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Cells 2017, 40:90–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powell JR, Ausubel FM: Models of Caenorhabditis elegans Infection by Bacterial and Fungal Pathogens. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;415:403–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim D: Studying host-pathogen interactions and innate immunity in Caenorhabditis elegans. DMM Dis Model Mech 2008, 1:205–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irazoqui JE, Troemel ER, Feinbaum RL, Luhachack LG, Cezairliyan BO, Ausubel FM: Distinct pathogenesis and host responses during infection of C. elegans by P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. PLoS Pathog 2010, 6:1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samuel BS, Rowedder H, Braendle C, Félix MA, Ruvkun G: Caenorhabditis elegans responses to bacteria from its natural habitats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113:E3941–Ε3949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *8.Kang D, Kirienkoa DR, Webster P, Fisher AL, Kirienko N V.: Pyoverdine, a siderophore from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, translocates into C. elegans, removes iron, and activates a distinct host response. Virulence 2018, 9:804–817.This study identified P. aeruginosa virulence factor Pyoveridine as the major effector that causes mitochondrial dysfunction by removal of Iron.

- 9.Claeys M, Waele KU Leuven DD, Borgonje G, Claevs M, Leyns F, Arnaut G, Waele D DE, Coomans A: Effect of nematicidal Bacillus thuringiensis strains on free-living nematodes : 2. Ultrastructural analysis of the intoxication process in Caenorhabditis elegans. Fundamental and Applied Nematology 1996, 19:407–414. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huffman DL, Bischof LJ, Griffitts JS, Aroian R V: Pore worms: Using Caenorhabditis elegans to study how bacterial toxins interact with their target host. Int J Med Microbiol. 2004. April;293(7–8):599–607. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kho MF, Bellier A, Balasubramani V, Hu Y, Hsu W, Nielsen-LeRoux C, McGillivray SM, Nizet V, Aroian R V.: The pore-forming protein Cry5B elicits the pathogenicity of Bacillus sp. against Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS One, 2011; 6(12): e29122. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaeberlein TL, Smith ED, Tsuchiya M, Welton KL, Thomas JH, Fields S, Kennedy BK, Kaeberlein M: Lifespan extension in Caenorhabditis elegans by complete removal of food. Aging Cell 2006, 5:487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avery L, Shtonda BB: Food transport in the C. elegans pharynx. J Exp Biol 2003, 206:2441–2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuen GJ, Ausubel FM: Both live and dead Enterococci activate Caenorhabditis elegans host defense via immune and stress pathways. Virulence 2018, 9:683–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahajan-Miklos S, Tan M-W, Rahme LG, Ausubel FM: Molecular Mechanisms of Bacterial Virulence Elucidated Using a Pseudomonas aeruginosa-Caenorhabditis elegans Pathogenesis Model. Cell. January 8;96(1):47–56. 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cezairliyan B, Vinayavekhin N, Grenfell-Lee D, Yuen GJ, Saghatelian A, Ausubel FM: Identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Phenazines that Kill Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Pathog 2013. January; 9(1): e1003101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunbar TL, Yan Z, Balla KM, Smelkinson MG, Troemel ER: C. elegans detects pathogen-induced translational inhibition to activate immune signaling. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 11:375–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McEwan DL, Kirienko NV, Ausubel FM: Host translational inhibition by Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A triggers an immune response in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 11:364–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirienko N V, Ausubel FM, Ruvkun G: Mitophagy confers resistance to siderophore-mediated killing by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112:1821–1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **20.Singh J, Aballay A: Microbial Colonization Activates an Immune Fight-and-Flight Response via Neuroendocrine Signaling. Dev Cell 2019, 49:89–99.e4This study identified intestinal distension by accumulation of pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria can activate C. elegans host defense responses and pathogen avoidance mediated by neuropeptides.

- *21.Labed SA, Wani KA, Jagadeesan S, Hakkim A, Najibi M, Irazoqui JE: Intestinal Epithelial Wnt Signaling Mediates Acetylcholine-Triggered Host Defense against Infection. Immunity 2018, 48:963–978.e4.This study discovered that endogenous acetylcholine levels are increased during S. aureus infection and required for host defense. ACh acts in a neuroendocrine manner to activate muscarinic receptors in the intestine, driving expression of antimicrobials at the site of infection via WNT signaling.

- 22.Dimov I, Maduro MF: The C. elegans intestine: organogenesis, digestion, and physiology. Cell Tissue Res 2019, 377:383–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiecolt-Glaser JK: Stress, food, and inflammation: Psychoneuroimmunology and nutrition at the cutting edge. Psychosom Med 2010, 72:365–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan M, Mahajan-miklos S, Ausubel FM: Killing of Caenorhabditis elegans by Pseudomonas aeruginosa used to model mammalian bacterial pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.1999. January 19;96(2):715–20. 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garsin DA, Sifri CD, Mylonakis E, Qin X, Singh K V, Murray BE, Calderwood SB, Ausubel FM: A simple model host for identifying Gram-positive virulence factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001. September 11;98(19):10892–7 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tremaroli V, Bäckhed F: Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature 2012, 489:242–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *27.Nhan JD, Turner CD, Anderson SM, Yen CA, Dalton HM, Cheesman HK, Ruter DL, Naresh NU, Haynes CM, Soukas AA, et al. : Redirection of SKN-1 abates the negative metabolic outcomes of a perceived pathogen infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116:22322–22330.This study showed for the first time that C. elegans looses somatic lipids upon P. aeruginosa infection and that this is mediated by the SKN-1 pathway. SKN-1 activation of immune genes comes at the cost of loss of lipid metabolism homeostasis.

- 28.Dasgupta M, Shashikanth M, Gupta A, Sandhu A, De A, Javed S, Singh V: NHR-49 transcription factor regulates immuno-metabolic response and survival of Caenorhabditis elegans during Enterococcus faecalis infection. Infect Immun 2020, doi: 10.1128/IAI.00130-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tissenbaum HA: DAF-16: FOXO in the Context of C. elegans. Curr Top Dev Biol 2018, 127:1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Gilst MR, Hadjivassiliou H, Jolly A, Yamamoto KR: Nuclear hormone receptor NHR-49 controls fat consumption and fatty acid composition in C. elegans. PLoS Biol 2005, 3:0301–0312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lambeth JD: NOX enzymes and the biology of reactive oxygen. Nat Rev Immunol 2004, 4:181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miranda-Vizuete A, Veal EA: Caenorhabditis elegans as a model for understanding ROS function in physiology and disease. Redox Biol 2017, 11:708–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chávez V, Mohri-Shiomi A, Maadani A, Vega LA, Garsin DA: Oxidative stress enzymes are required for DAF-16-mediated immunity due to generation of reactive oxygen species by Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 2007, 176:1567–1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **34.Chávez V, Mohri-Shiomi A, Garsin DA: Ce-Duox1/BLI-3 generates reactive oxygen species as a protective innate immune mechanism in Caenorhabditis elegans. Infect Immun 2009, 77:4983–4989.This was the first study that showed DUX mediated ROS generation upon infection in C. elegans. It also established that DUOX mediated ROS generation is important for resistance to E. faecalis infection.

- 35.Dryden M: Reactive oxygen species: a novel antimicrobial. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2018, 51:299–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang J, Wang X, Vikash V, Ye Q, Wu D, Liu Y, Dong W: ROS and ROS-Mediated Cellular Signaling. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016:4350965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Der Hoeven R, Cruz MR, Chávez V, Garsin DA: Localization of the dual oxidase BLI-3 and characterization of its NADPH oxidase domain during infection of Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS One 2015. April 24;10(4):e0124091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hwang AB, Ryu EA, Artan M, Chang HW, Kabir MH, Nam HJ, Lee D, Yang JS, Kim S, Mair WB, et al. : Feedback regulation via AMPK and HIF-1 mediates ROS-dependent longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111:E4458–E4467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jansen WTM, Bolm M, Balling R, Chhatwal GS, Schnabel R: Hydrogen peroxide-mediated killing of Caenorhabditis elegans by Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect Immun 2002, 70:5202–5207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Back P, Braeckman BP, Matthijssens F: ROS in aging Caenorhabditis elegans: Damage or signaling? Oxid Med Cell Longev 2012, doi: 10.1155/2012/608478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanz A: Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species: Do they extend or shorten animal lifespan? Biochim Biophys Acta - Bioenerg 2016, 1857:1116–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kwon S, Kim EJE, Lee SJV.: Mitochondria-mediated defense mechanisms against pathogens in Caenorhabditis elegans. BMB Rep 2018, 51:274–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levine RL, Stadtman ER: Oxidative modification of proteins during aging. Exp Gerontol. 2001. September;36(9):1495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davies MJ: Protein oxidation and peroxidation. Biochem J 2016, 473:805–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li L, Tan J, Miao Y, Lei P, Zhang Q: ROS and Autophagy: Interactions and Molecular Regulatory Mechanisms. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2015, 35:615–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ray A, Martinez BA, Berkowitz LA, Caldwell GA, Caldwell KA: Mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and neurodegeneration elicited by a bacterial metabolite in a C. elegans Parkinson’s model. Cell Death Dis. 2014. January 9;5(1):e984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sem XH, Rhen M: Pathogenicity of Salmonella enterica in Caenorhabditis elegans Relies on Disseminated Oxidative Stress in the Infected Host. PLoS One 2012, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Putker M, Madl T, Vos HR, de Ruiter H, Visscher M, van den Berg MCW, Kaplan M, Korswagen HC, Boelens R, Vermeulen M, et al. : Redox-Dependent Control of FOXO/DAF-16 by Transportin-1. Mol Cell 2013, 49:730–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garsin DA, Villanueva JM, Begun J, Kim DH, Sifri CD, Calderwood SB, Ruvkun G, Ausubel FM: Long-lived C. elegans daf-2 Mutants are resistant to bacterial pathogens. Science (80-) 2003, 300:1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van der Hoeven R, McCallum KC, Cruz MR, Garsin DA: Ce-Duox1/BLI-3 generated reactive oxygen species trigger protective SKN-1 activity via p38 MAPK signaling during infection in C. elegans. PLoS Pathog. 2011. December;7(12):e1002453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Inoue H, Hisamoto N, Jae HA, Oliveira RP, Nishida E, Blackwell TK, Matsumoto K: The C. elegans p38 MAPK pathway regulates nuclear localization of the transcription factor SKN-1 in oxidative stress response. Genes Dev 2005, 19:2278–2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hall JA, McElwee MK, Freedman JH: Identification of ATF-7 and the insulin signaling pathway in the regulation of metallothionein in C. elegans suggests roles in aging and reactive oxygen species. PLoS One. 2017. June 20;12(6):e0177432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee SJ, Hwang AB, Kenyon C: Inhibition of respiration extends C. elegans life span via reactive oxygen species that increase HIF-1 activity. Curr Biol 2010, 20:2131–2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Visvikis O, Ihuegbu N, Labed SA, Luhachack LG, Alves AMF, Wollenberg AC, Stuart LM, Stormo GD, Irazoqui JE: Innate host defense requires TFEB-mediated transcription of cytoprotective and antimicrobial genes. Immunity 2014, 40:896–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen H Da Kao CY, Liu BY Huang SW, Kuo CJ Ruan JW, Lin YH Huang CR, Chen YH Wang HD, et al. : HLH-30/TFEB-mediated autophagy functions in a cell-autonomous manner for epithelium intrinsic cellular defense against bacterial pore-forming toxin in C. elegans. Autophagy 2017, 13:371–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *56.Kumsta C, Chang JT, Schmalz J, Hansen M: Hormetic heat stress and HSF-1 induce autophagy to improve survival and proteostasis in C. Elegans. Nat Commun. 2017. February 15;8:14337.This study showed that HSF-1 induction by heat shock or overexpression activates autophagy. Induction of autophagy also reduced aggregation of PolyQ aggregates.

- 57.Leiser SF, Miller H, Rossner R, Fletcher M, Leonard A, Primitivo M, Rintala N, Ramos FJ, Miller DL, Kaeberlein M: Cell nonautonomous activation of flavin-containing monooxygenase promotes longevity and health span. Science. 2015. December 11;350(6266):1375–1378.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kikis EA: The struggle by Caenorhabditis elegans to maintain proteostasis during aging and disease. Biol Direct. 2016. November 3;11(1):58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mohri-Shiomi A, Garsin DA: Insulin signaling and the heat shock response modulate protein homeostasis in the Caenorhabditis elegans intestine during infection. J Biol Chem 2008, 283:194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brieger K, Schiavone S, Miller FJ, Krause KH: Reactive oxygen species: From health to disease. Swiss Med Wkly 2012, 142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lévy E, El Banna N, Baïlle D, Heneman-Masurel A, Truchet S, Rezaei H, Huang ME, Béringue V, Martin D, Vernis L: Causative links between protein aggregation and oxidative stress: A review. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sesti F, Liu S, Cai SQ: Oxidation of potassium channels by ROS: a general mechanism of aging and neurodegeneration? Trends Cell Biol 2010, 20:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Darby C, Cosma CL, Thomas JH, Manoil C: Lethal paralysis of Caenorhabditis elegans by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999. December 21;96(26):15202–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Blackwell TK, Steinbaugh MJ, Hourihan JM, Ewald CY, Isik M: SKN-1/Nrf, stress responses, and aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Free Radic Biol Med 2015, 88:290–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao L, Zhao Y, Liu R, Zheng X, Zhang M, Guo H, Zhang H, Ren F: The transcription factor DAF-16 is essential for increased longevity in C. elegans Exposed to Bifidobacterium longum BB68. Sci Rep 2017, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hu Q, D’Amora DR, MacNeil LT, Walhout AJM, Kubiseski TJ: The caenorhabditis elegans oxidative stress response requires the NHR-49 transcription factor. G3 Genes, Genomes, Genet 2018, 8:3857–3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morley JF, Morimoto RI: Regulation of Longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans by Heat Shock Factor and Molecular Chaperones. Mol Biol Cell 2004, 15:657–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Singh V, Aballay A: Heat-shock transcription factor (HSF)-1 pathway required for Caenorhabditis elegans immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006. August 29;103(35):13092–7.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ooi FK, Prahlad V: Olfactory experience primes the heat shock transcription factor HSF-1 to enhance the expression of molecular chaperones in C. elegans. Sci Signal. 2017. October 17;10(501):eaan4893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Melber A, Haynes CM: UPR mt regulation and output: A stress response mediated by mitochondrial-nuclear communication. Cell Res 2018, 28:281–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Martínez G, Duran-Aniotz C, Cabral-Miranda F, Vivar JP, Hetz C: Endoplasmic reticulum proteostasis impairment in aging. Aging Cell 2017, 16:615–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nargund AM, Pellegrino MW, Fiorese CJ, Baker BM, Haynes CM: Mitochondrial import efficiency of ATFS-1 regulates mitochondrial UPR activation. Science (80-) 2012, 337:587–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pellegrino MW, Nargund AM, Kirienko NV, Gillis R, Fiorese CJ, Haynes CM: Mitochondrial UPR-regulated innate immunity provides resistance to pathogen infection. Nature 2014, 516:414–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Walter P, Ron D: The Unfolded Protein Response: From Stress Pathway to Homeostatic Regulation. Science. 2011. November 25;334(6059):1081–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Richardson CE, Kooistra T, Kim DH: An essential role for XBP-1 in host protection against immune activation in C. elegans. Nature 2010, 463:1092–1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hourihan JM, Moronetti Mazzeo LE, Fernández-Cárdenas LP, Blackwell TK: Cysteine Sulfenylation Directs IRE-1 to Activate the SKN-1/Nrf2 Antioxidant Response. Mol Cell 2016, 63:553–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Papaevgeniou N, Chondrogianni N: The ubiquitin proteasome system in Caenorhabditis elegans and its regulation. Redox Biol 2014, 2:333–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Komander D, Rape M: The Ubiquitin Code. Annu Rev Biochem 2012, 81:203–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bakowski MA, Desjardins CA, Smelkinson MG, Dunbar TA, Lopez-Moyado IF, Rifkin SA, Cuomo CA, Troemel ER: Ubiquitin-Mediated Response to Microsporidia and Virus Infection in C. elegans. PLoS Pathog. 2014. June 19;10(6):e1004200. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004200. eCollection 2014 Jun. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *80.Ron D, Lehrbach NJ, Ruvkun G: Endoplasmic reticulum-associated SKN-1A/Nrf1 mediates a cytoplasmic unfolded protein response and promotes longevity. Elife. 2019. April 11;8:e44425.SKN-1A/Nrf1 is activated by multiple stressors, this study showed accumulation of unfolded proteins also activates SKN-1A/Nrf1. Once activated, SKN-1A/Nrf1 drives upregulation of proteasome subunits to restore proteostasis

- 81.Kuo CJ, Hansen M, Troemel E: Autophagy and innate immunity: Insights from invertebrate model organisms. Autophagy 2018, 14:233–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Palikaras K, Lionaki E, Tavernarakis N: Coordination of mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis during ageing in C. elegans. Nature 2015, 521:525–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fiorese CJ, Schulz AM, Lin YF, Rosin N, Pellegrino MW, Haynes CM: The Transcription Factor ATF5 Mediates a Mammalian Mitochondrial UPR. Curr Biol 2016, 26:2037–2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Oliveira RP, Abate JP, Dilks K, Landis J, Ashraf J, Murphy CT, Blackwell TK: Condition-adapted stress and longevity gene regulation by Caenorhabditis elegans SKN-1/Nrf. Aging Cell 2009, 8:524–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zou CG, Ma YC, Dai LL, Zhang KQ: Autophagy protects C. elegans against necrosis during Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111:12480–12485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yang Y, Bazhin AV, Werner J, Karakhanova S: Reactive oxygen species in the immune system. Int Rev Immunol 2013, 32:249–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lapierre LR, De Magalhaes Filho CD, McQuary PR, Chu CC, Visvikis O, Chang JT, Gelino S, Ong B, Davis AE, Irazoqui JE, et al. : The TFEB orthologue HLH-30 regulates autophagy and modulates longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dierking K, Yang W, Schulenburg H: Antimicrobial effectors in the nematode caenorhabditis elegans: An outgroup to the arthropoda. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2016. May 26;371(1695):20150299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lee KA, Kim SH, Kim EK, Ha EM, You H, Kim B, Kim MJ, Kwon Y, Ryu JH, Lee WJ: Bacterial-derived uracil as a modulator of mucosal immunity and gut-microbe homeostasis in drosophila. Cell 2013, 153:797–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zou CG, Tu Q, Niu J, Ji XL, Zhang KQ: The DAF-16/FOXO Transcription Factor Functions as a Regulator of Epidermal Innate Immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(10):e1003660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bae YS, Choi MK, Lee WJ: Dual oxidase in mucosal immunity and host-microbe homeostasis. Trends Immunol 2010, 31:278–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhou R, Tardivel A, Thorens B, Choi I, Tschopp J: Thioredoxin-interacting protein links oxidative stress to inflammasome activation. Nat Immunol 2010, 11:136–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Stocks CJ, Schembri MA, Sweet MJ, Kapetanovic R: For when bacterial infections persist: Toll-like receptor-inducible direct antimicrobial pathways in macrophages. J Leukoc Biol 2018, 103:35–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Meisel JD, Panda O, Mahanti P, Schroeder FC, Kim DH: Chemosensation of bacterial secondary metabolites modulates neuroendocrine signaling and behavior of C. elegans. Cell 2014, 159:267–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kim DH, Ewbank JJ: Signaling in the innate immune response. WormBook 2018, 2018:1–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Singh J, Aballay A: Neural control of behavioral and molecular defenses in C. elegans. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2020, 62:34–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Prahlad V, Morimoto RI: Integrating the stress response: lessons for neurodegenerative diseases from C. elegans. Trends Cell Biol 2009, 19:52–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]