Abstract

Preeclampsia is a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy that can involve dangerous neurological symptoms such as spontaneous seizures (eclampsia). Despite being diseases specific to the pregnant state, preeclampsia and eclampsia have long-lasting neurological consequences later in life, including changes in brain structure and cognitive decline at relatively young ages. However, the effects of preeclampsia on brain regions central to memory and cognition, such as the hippocampus, are unclear. Here, we present a case reporting the progressive and permanent cognitive decline in a woman that had eclamptic seizures in the absence of evidence of brain injury on MRI. We then use rat models of normal pregnancy and preeclampsia to investigate mechanisms by which eclampsia-like seizures may disrupt hippocampal function. We show that experimental preeclampsia causes delayed memory decline in rats and disruption of hippocampal neuroplasticity. Further, seizures in pregnancy and preeclampsia caused acute memory dysfunction and impaired neuroplasticity but did not cause acute neuronal cell death. Importantly, hippocampal dysfunction persisted 5 weeks postpartum, suggesting seizure-induced injury is long lasting and may be permanent. Our data provide the first evidence of a model of preeclampsia that may mimic the cognitive decline of formerly preeclamptic women, and that preeclampsia and eclampsia affect hippocampal network plasticity and impair memory.

Keywords: Pregnancy, preeclampsia, eclamptic seizures, early-onset dementia, hippocampal neuroplasticity

Introduction

Preeclampsia is a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy that complicates up to 10% of pregnancies world-wide and is one of the greatest causes of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality (MacKay et al., 2001; Steegers et al., 2010). Although preeclampsia is a disorder of pregnancy, its consequences are far reaching and can extend decades into the postpartum years. In fact, preeclampsia is no longer considered a disease only of pregnancy, but is now recognized to have long-lasting consequences for mother and development of the baby (Amaral et al., 2015). Preeclampsia is a major risk factor for future cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, including hypertension, heart failure and stroke (Amaral et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2019; Valdes, 2017). Further, preeclampsia appears to have long-lasting neurological consequences. Women who had pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia have brain atrophy and cognitive decline, particularly memory and executive dysfunction (e.g. working memory, flexible thinking), later in life and at relatively young ages (Brusse et al., 2008; Dayan et al., 2018; Elharram et al., 2018; Fields et al., 2017; Siepmann et al., 2017).

The underlying mechanisms by which preeclampsia promotes cognitive decline are not known, but likely involve hippocampal dysfunction given the central role of this deep brain structure in memory and cognition. Preeclampsia is also associated with a high incidence of spontaneous seizures (eclampsia) that are not benign. Acute memory deficits are common in women with eclampsia, with either retrograde or anterograde amnesia lasting hours to days post-seizure (Shah et al., 2008). Importantly, memory dysfunction can persist months and years after eclamptic seizures (Andersgaard et al., 2009; Shah et al., 2008). Eclampsia can include recurrent and/or prolonged seizures, including status convulsions, but how the hippocampus is adversely affected by seizure during preeclampsia to promote memory decline later in life is not known. Further, studies report that up to 40% of eclampsia occurs in women with seemingly normal pregnancies, that is in the absence of hypertension or the diagnosis of preeclampsia (Douglas and Redman, 1994). We and others have shown that pregnancy results in a hyperexcitable maternal brain due to downregulation of GABA receptors in the hippocampus occurring in response to elevated neurosteroid metabolites (e.g. allopregnanolone) (Johnson et al., 2015; Maguire et al., 2009). While it is clear that the pregnant state increases the susceptibility to seizures, whether pregnancy or preeclampsia potentiate seizure-induced hippocampal dysfunction is not known.

Studies investigating the effects of preeclampsia and eclampsia on the maternal brain have been limited in humans to imaging and neurocognitive testing. On MRI, women with a history of preeclampsia have greater cerebral white matter lesion burden and decreased cortical grey matter volume later in life compared to women that had a healthy pregnancy (Aukes et al., 2012; Siepmann et al., 2017). In addition to structural changes in the brain, women who had preeclampsia report cognitive impairment, particularly memory dysfunction (Brusse et al., 2008; Fields et al., 2017; Postma et al., 2014; Postma et al., 2013), suggesting preeclampsia predisposes the brain to early-onset cognitive decline that may be exacerbated by eclamptic seizures. Mechanisms by which preeclampsia and eclampsia affect the hippocampus remain unclear, and cannot safely be investigated in women. Therefore, the use of animal models are necessary to better understand neurological consequences of preeclampsia and eclampsia, especially the acute and prolonged effects on memory and hippocampal function.

Here we present a case report describing the post-partum cognitive decline of a patient that presented with prolonged, severe eclamptic seizures. The delayed memory decline and disrupted hippocampal network function was then investigated in a rat model of experimental preeclampsia (ePE) that mimicked the early-onset cognitive decline. In addition, we report that eclamptic seizures (e.g. seizures during pregnancy and ePE), but not seizures in the virgin state, caused acute memory dysfunction due to impaired hippocampal neuronal plasticity, but not overt neuronal cell death. This effect persisted weeks after pregnancy suggesting the injury may be permanent. Lastly, we show the hippocampus may be predisposed to seizure-induced network dysfunction via pregnancy-induced changes in excitatory NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptor function. These findings highlight the treatment potential in restoring hippocampal network function and easing the cognitive burden associated with preeclampsia and eclampsia to improve maternal cognitive health.

Materials and methods

Animals

Experiments were conducted using a total of 158 timed-pregnant or virgin Sprague Dawley female rats between 14 – 18 weeks of age (Charles River, Canada). Pregnant rats (~ 380 – 460 gm) were used either late in gestation (day 19 – 21 of a 22 day gestation), a time point when eclampsia occurs most often (Douglas and Redman, 1994) or 5 weeks post-partum. All virgin rats (~ 300 – 340 gm) were used during the same phase of the estrus cycle (metestrus) to avoid potential effects of sex steroids on seizure susceptibility and hippocampal function. Details regarding animal housing can be found in Supplementary Material.

Model of experimental preeclampsia (ePE)

Preeclampsia is a state of widespread maternal endothelial dysfunction thought to be due to dyslipidemia that can manifest as hypertension, endothelial dysfunction, increased large artery stiffness, and placental disease (Davidge et al., 2014; Granger et al., 2001; Lamarca, 2012; Myatt, 2002; Robb et al., 2009; Sankaralingam et al., 2009). We used an established model of ePE that involved maintaining pregnant rats on a high cholesterol diet (Prolab 3000 rat chow with 2 % cholesterol and 0.5 % sodium cholate; Scotts Distributing Inc., Hudson, NH, USA) days 7 – 21 of gestation (Johnson and Cipolla, 2016). This model induces dyslipidemia similar to preeclamptic women, and causes other preeclampsia-like symptoms including maternal endothelial dysfunction and increased blood pressure(Johnson and Cipolla, 2018; Schreurs and Cipolla, 2013; Schreurs et al., 2013). For post-partum studies, ePE rats were maintained on the high cholesterol diet until experimental use. Litters were weaned at postnatal day 21 and post-partum rats allowed ~ 7 days before handing for behavioral tasks and terminal experiments. Please see the Supplementary Material for assessment of large artery stiffness, blood pressure and pregnancy outcome.

Seizure induction and assessment of seizure severity

Eclampsia-like seizures were induced using the chemoconvulsant pentylenetetrazole (PTZ; Millipore-Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) that was administered i.p. to induce tonic-clonic seizures in conscious, unrestrained pregnant (Preg), ePE and virgin rats. On day 19 of gestation, rats received multiple PTZ injections to induce prolonged seizures (5 – 40 mg/kg; n=6–8/group; N=60), or vehicle (no-seizure control; n=6–8/group; N=54). After a 30 min period of seizures including two or more tonic-clonic seizures lasting ≥ 5 min and intermittent lower grade seizures (Cherian and Thomas, 2009), rats received a clinically relevant dose of magnesium sulfate (MgSO4; 270 mg/kg i.p.; Millipore-Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), the standard of care in preeclamptic women for prevention and cessation of eclamptic seizures (Figure 1). Separate groups of Preg, ePE and virgin rats (n=8/group; N=24) received one PTZ injection to induce a single tonic-clonic seizure (60 mg/kg or vehicle) and received MgSO4 20 min later to determine whether pregnancy or ePE increased the susceptibility to seizure-induced hippocampal injury. Seizure severity was assessed using a Racine scale modified specifically for PTZ-induced convulsions in rats (Supplementary Table 1) (Luttjohann et al., 2009). All seizures were induced between 12:00 pm and 3:00 pm to limit potential effects of time of day on seizure susceptibility and were video monitored. See Supplementary Material for details regarding the pilot study performed to determine PTZ dosing and justification for the use of PTZ to model eclampsia.

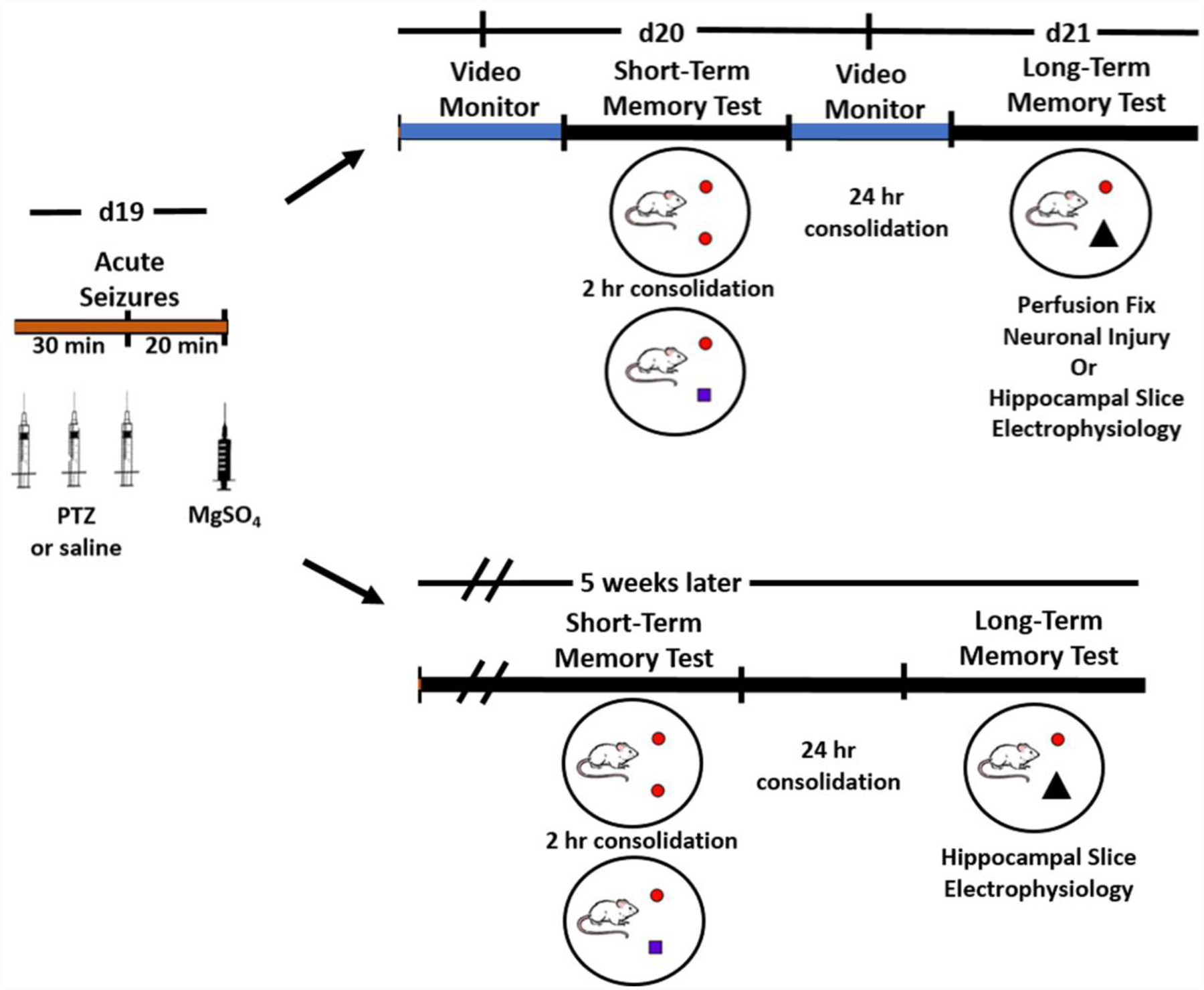

Figure 1. Experimental Paradigm.

Acute eclamptic seizures were induced on d19 of gestation of rats with normal pregnancy (Preg) or experimental preeclampsia (ePE), or age-matched virgin rats via pentylenetetrazole (PTZ), or saline, injections every 10 minutes to induce 30 min of convulsions. Rats received magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) 20 min after seizures. To investigate acute effects of seizures on memory function during Preg and ePE, short-term memory and long-term memory were tested 24 hr and 48 hr after seizures, respectively, using a novel object recognition task. Rats were then either transcardially perfused for assessment of neuronal injury in the brain or hippocampal slice electrophysiology performed. To determine long-lasting effects of seizures, rats had short-term and long-term memory tested five weeks after seizures, and hippocampal slice electrophysiology performed.

Behavioral tests

To determine the effect of seizures on memory function, short-term memory (STM) and long-term memory (LTM) were tested 24 and 48 hr (N=72) or 5 weeks (N=24) after seizures using a novel object recognition (NOR) task (Broadbent et al., 2010; Johnson et al., 2019). The time spent investigating both the novel and familiar objects was quantified using automated live tracking software (ANY-maze, Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL, USA) and used to calculate a recognition index as a measure of memory function: TimeNovel / TimeTotal, where TimeNovel is the amount of time (sec) spent investigating the novel object, and TimeTotal is the amount of time (sec) spent investigating both the novel and familiar objects. See the Supplementary Material for specific parameters of the NOR task. One Preg and three virgin no-seizure control rats that were used experimentally in the acute phase after seizures did not explore any object during the acquisition phase of the NOR task and were excluded.

Hippocampal slice electrophysiology

To investigate seizure-induced changes in hippocampal synaptic plasticity, hippocampal slice electrophysiology was performed in separate groups of Preg, ePE and virgin rats that either had seizures or were no-seizure controls (n=6/group; N=60) as described previously (Orfila et al., 2017). Hippocampal neuronal network plasticity was assessed by measuring long-term potentiation (LTP) of the CA3 – CA1 Schaffer Collateral pathway. Pulses were evoked at 0.05 Hz and a stable baseline period of field excitatory post-synaptic potentials (fEPSPs) were recorded for 20 min before delivering a theta burst stimulation (TBS) train. After TBS, fEPSPs were recorded for 60 min. The slope of the fEPSP was measured (dV/dT) and time course graphs were created by averaging the normalized fEPSP slope values and plotting them as the percent change from baseline (referenced to 100%) over the recording period. The average of the fEPSP slope value from min 50 – 60 after TBS was divided by the average of the fEPSP slope value from 10 – 20 min prior to TBS to calculate the fold-change in slope as a measure of potentiation. Additional details on acquisition of slice electrophysiology data can be found in Supplementary Material.

Histology of brain sections to assess neuronal injury

Forty-eight hours after seizures, some rats underwent transcardial perfusion fixation under isoflurane anesthesia (3% in O2) and 2 mm coronal brain sections taken of the posterior cerebral cortex (3 – 5 mm posterior to bregma) containing the dorsal hippocampus, perirhinal cortex and retrosplenial cortex and paraffin embedded for histological assessments of neuronal injury (n=8/group; N=48). Histology was performed on 5 μm thick brain sections using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to confirm consistent location within the dorsal hippocampus and to determine neuronal death. H&E staining was performed using standard methodology. Images of hippocampal regions CA1, CA3, dentate gyrus and hilus were captured using an Olympus BX50 light microscope (20X) and assessed for neuronal pyknosis (condensed nuclei) and neuronal loss. Fluorescent immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed on three 5 μm thick serial brain sections using primary antibodies for cleaved caspase-3 (anti-rabbit; 1:250; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Beverly, MA, USA), RIP3 (receptor-interacting protein 3; anti-mouse; 1:100; Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA), and 3-NT (3-nitrotyrisine; anti-mouse; 10μg/mL; Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). Each primary antibody was co-stained with NeuN (anti-mouse; 2μg/mL; Millipore or anti-rabbit; 1.13μg/mL; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). All images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal microscope (20X) and constant imaging parameters. Images were digitized and imported into image analysis software (Metamorph, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) for quantification of caspase 3+, RIP3+ or 3-NT+ staining within the neuronal layers of the hippocampus (CA1, CA3, dentate gyrus, hilus) and cortex (perirhinal and retrosplenial), as evidenced by NeuN+ staining. A constant pixel threshold within the image analysis software was used to determine positive expressing cells. Cell counts were normalized to the area of neuronal layer within the region investigated and averaged per group. See Supplementary Material for more details on perfusion fixation, IHC and imaging parameters.

NMDA receptor subunit expression by Western blot

Separate groups of Preg and virgin rats (n=10/group; N=20) were euthanized under isoflurane anesthesia and hippocampi dissected, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80°C until use. Total and phosphorylated hippocampal NMDA receptor subunit protein expression was determined using the following primary antibodies: anti-NMDAR1 ([1 μg/mL]; BD Pharmigen, San Diego, CA, USA), anti-phospho-NMDAR1 (Ser890) (1:500; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-NR2A ([5 μg/mL]; Antibodies Inc., Davis, CA, USA), anti-phospho-NMDAR2A (Tyr1246) (1:500; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-NR2B ([5 μg/mL]; Antibodies Inc., Davis, CA, USA), and anti-phospho-NMDAR2B (Tyr1472) (1:500; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA). Western blots were imaged using the Odyssey Classic by LI-COR (Lincoln, NE, USA). β-actin served as a loading control (1:5000; Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). All samples were normalized to β-actin. See Supplementary Material for details on tissue preparation, protein loading and secondary antibodies used.

Statistical analysis

The number of animals used in each experiment was determined by a statistical power calculation using a two-sided 95 % confidence interval for a single mean and 1 - β of 0.80 based on previous and preliminary studies using similar methodology (Johnson et al., 2014; Orfila et al., 2017). All statistical testing was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). Results are presented as mean ± SEM and a p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant. To determine differences between two groups, a two-sided Student’s t-test was used. Comparisons between three groups were made using a one-way ANOVA with a post-hoc Bonferroni test, and between four or more groups using a two-way ANOVA with a post-hoc Tukey test to determine the interaction between independent variables (e.g. pregnancy status and seizures). Rats were randomized to treatment group, and the order of experiments were randomized using an online randomization tool (Random.org). All experiments and data analyses were completed blinded to group.

Study approval

Written consent was received from the patient for the inclusion of the medical records and detailed experiences contained within this case report. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All euthanasia was under isoflurane anesthesia according to NIH guidelines, and experiments were conducted and are reported in compliance with the Animal Research: Reporting in Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines.

Data availability

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

Results

Case report

A 43 year old pregnant woman reported feeling ill, having severe headaches and exhibited “staring episodes” at 26 weeks of gestation. Blood pressure was elevated 130/80 – 160/90 at semi-weekly doctor’s visits, and proteinuria reported to be 361 mg/24 hr. Two weeks later, the patient had a generalized seizure at her home and was admitted to the emergency department 40 min later in critical condition. The patient was lethargic, had decreased responsiveness upon arrival, and had multiple (≥ 5) generalized, tonic-clonic seizures lasting ≥ 5 minutes with loss of consciousness. The time course of seizure treatment at the hospital was as follows: thirteen minutes after onset of tonic-clonic seizures, the patient was administered 4 grams i.v. of MgSO4. Seizures continued and 130 mg phenobaritol was administered via i.v. push three minutes later. Seizures continued until 10 mg diazepam was administered via i.v.push 33 min after seizure onset, and the patient was intubated, ventilated and put into a medically induced coma. The pregnant patient was diagnosed with eclampsia with status epilepticus, defined as multiple tonic-clonic seizures with intermittent loss of consciousness lasting a period of 30 minutes or longer. An emergency cesarean section was performed. The patient remained in the critical care unit intubated and ventilated for 24 hr. Two days after eclampsia, the patient underwent an MRI that was negative for lesions, hemorrhage, tumor, ischemic changes or white matter injury, and was discharged 4 days after admission.

After status convulsions in the context of eclampsia, the patient experienced progressive neurocognitive, neuropsychiatric and sensorimotor decline that is summarized in Table 1. Importantly, despite robust and devastating changes in multiple cognitive domains, new onset of mood disorders and deterioration of sensorimotor function, repeated MRI were negative for pathology and EEG was reported to be normal (i.e. no evidence of epileptiform or abnormal activity), suggesting the patient did not develop a seizure disorder or brain lesions. Six years after eclampsia, a psychological evaluation reported evidence of particularly left hemisphere cognitive decline associated with eclamptic seizures affecting sensory functions on the right, motor functions on the right, naming, verbal problem solving. Obvious impairment of piriform cortices resulting in olfactory hallucinations and impaired olfaction. The aggregate of her cognitive, behavioral and psychological impairments result in a variety of disabilities permanently affecting higher-level activities of daily living, psychosocial integration, and vocational independence. While there are no records of additional seizures in the six years the patient received follow-up care reported in Table 1, it is possible that delayed-onset epilepsy occurred in response to damage from the eclamptic seizures that was not detected via EEG that contributed to the progressive cognitive decline. Overall, this case demonstrates the debilitating and widespread cognitive, motor, sensory and psychological damage that can be the consequence of eclampsia, despite there being negative MRI findings for brain injury and normal EEG.

Table 1.

Summary of the time course of cognitive, sensorimotor and psychological decline after severe eclamptic seizures.

| Time After Eclampsia | Symptoms | MRI & EEG Findings |

|---|---|---|

| < 1 year |

|

MRI- negative |

| 1–2 years |

|

MRI- negative EEG- normal |

| 2–3 years |

|

EEG- normal |

| 3–4 years |

|

MRI- negative |

| 4–6 years |

|

Not completed |

Seizure-induced acute memory dysfunction

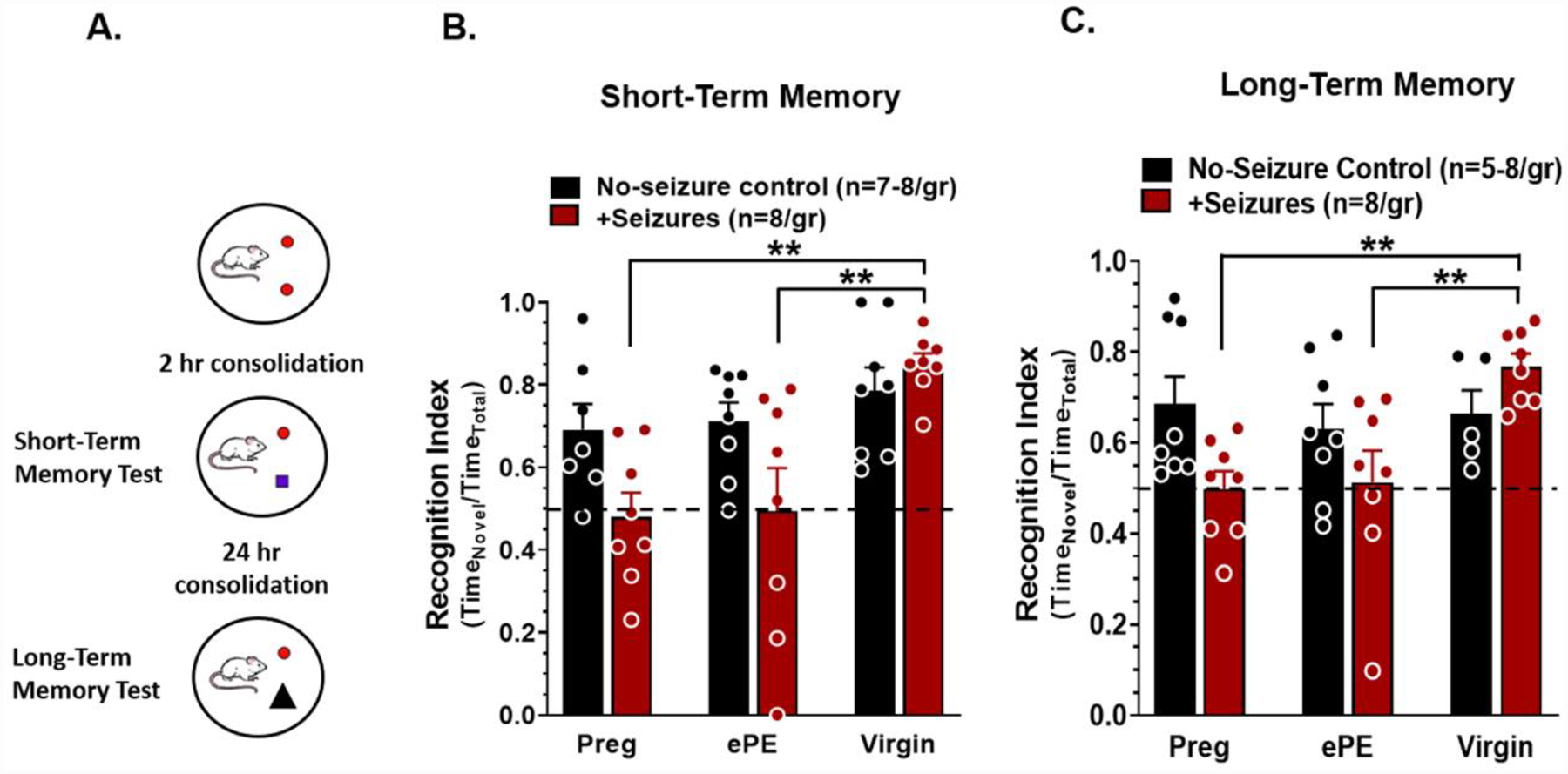

To better understand pathological mechanisms by which eclampsia causes cognitive dysfunction, we investigated acute effects of seizures on memory and hippocampal function in rat models of normal pregnancy and ePE, and compared to seizures in the virgin state 24–48 hr after seizures. This ePE model induces dyslipidemia and mimics several important aspects of the human disease, including elevated circulating proinflammatory cytokines, maternal endothelial dysfunction, elevated blood pressure, increased large vessel stiffness, fetal growth restriction and placental disease (Supplementary Figure 1) (Johnson and Cipolla, 2018; Lindheimer et al., 2009; Schreurs et al., 2013). Maternal body weights were similar between Preg and ePE rats (424 ± 5 gm vs. 430 ± 8 gm; p > 0.05). Figure 1 illustrates the experimental paradigm. STM was assessed after a 2 hr consolidation period and LTM assessed after a 24 hr consolidation period using a NOR task (Figure 2A). No-seizure control rats spent the majority of the time investigating the novel object, as indicated by recognition indices > 0.50. We did not observe differences between the no-seizure control groups, suggesting neither pregnancy nor ePE affected baseline STM (Figure 2B) or LTM (Figure 2C). However, Preg and ePE rats that had seizures spent equal time investigating the novel and familiar objects, and had lower recognition indices than virgin rats that had seizures, indicating seizures impaired both STM (two-way ANOVA, F2, 41 = 3.251, p<0.01; Figure 2B) and LTM (two-way ANOVA, F3, 39 = 3.721, p<0.01; Figure 2C) during pregnancy and ePE, but not in the virgin state. Differences in STM and LTM were not due to baseline behavioral differences, as locomotion and exploratory behavior were similar between groups (Supplementary Figure 2), and all rats explored each identical object for > 20 sec during the acquisition phase of the task. Differential effects of seizures on memory function were not due to more severe seizures occurring during pregnancy or ePE, as there were no differences in latency to or duration of seizures between groups (Supplementary Figure 3), and doses of PTZ were similar between groups (68.5 ± 3.2 mg/kg in virgin, 67.9 ± 1.3 mg/kg in Preg and 68.4 ± 1.5 mg/kg in ePE; p > 0.05). Severity scores were similar between groups (≥ 6.0/7.0), as assessed via a Racine Scale modified for PTZ-induced convulsions in rats (Supplementary Table 1). These results demonstrate that seizures caused acute memory dysfunction in Preg and ePE rats that did not occur in virgin rats, suggesting the pregnant state, but not ePE, increased the susceptibility of the brain to seizure-induced memory dysfunction.

Figure 2. Seizures acutely impair memory function in pregnant and ePE rats.

(A) Experimental scheme. 24 hr after seizures, short-term memory was tested after a 2 hr consolidation period and long-term memory tested 24 hr later using a novel object recognition task. Seizures during normal pregnancy (Preg) and experimental preeclampsia (ePE) impaired (B) short-term memory and (C) long-term memory by decreasing recognition index compared to no-seizure controls and virgin rats that had seizures. Data analyzed using a two-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey test for multiple comparisons. There was a significant interaction between the effects of pregnancy status and seizures on short-term memory (n=7–8 rats/group, **p<0.01, F2, 41 = 3.251) and long-term memory (n=5–8 rats/group, **p<0.01, F3, 39 = 3.721). Error bars are SEM.

To investigate whether the normal pregnant state or ePE increased the susceptibility of the brain to seizure-induced injury, memory function after a single tonic-clonic seizure was compared to those receiving multiple seizures. A single seizure did not affect memory function or cause hippocampal neuronal cell death in any group (data not shown), indicating that multiple and prolonged seizures are necessary to disrupt memory.

Acute memory impairment was associated with impaired hippocampal LTP but not neuronal injury

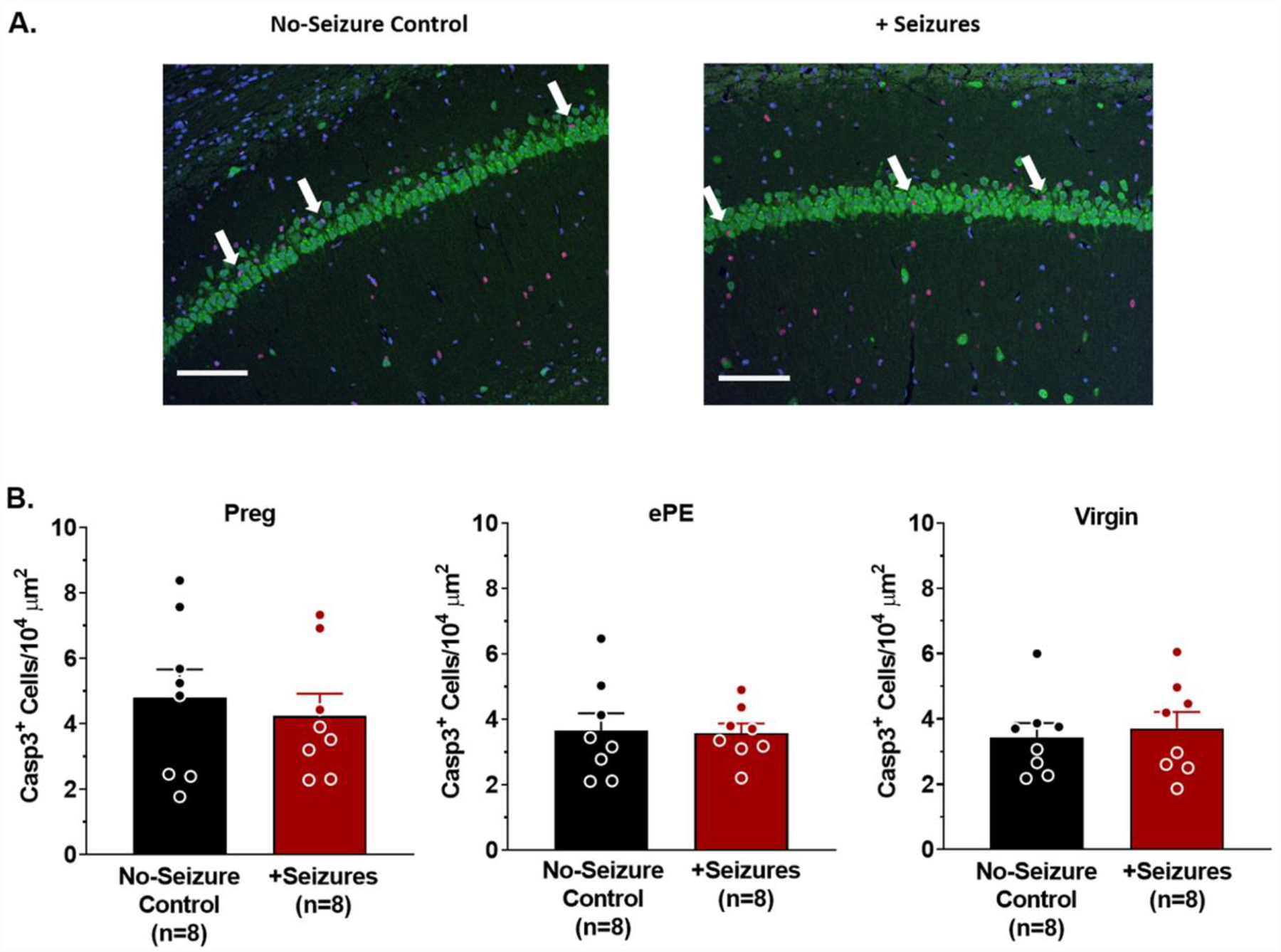

To determine whether impaired memory occurring after seizures in Preg and ePE rats was due to neuronal cell death, neuronal injury was assessed in CA1 of the hippocampus 48 hr after seizures. Several neuronal injury markers were used including caspase 3 (apoptosis), RIP3 (necroptosis), 3-NT (oxidative stress via peroxynitrite footprint) and H&E (pyknosis). Figure 3A shows representative images of caspase 3 staining in CA1 from a rat that was either a no-seizure control or that had prolonged and recurrent seizures. Caspase 3 staining was similar in CA1 between all groups (Figure 3B), and there was no detectable RIP3 or 3-NT staining in any group, or any evidence of neuronal loss via H&E (Supplementary Figure 4). There was no evidence of neuronal injury in other hippocampal regions (e.g. CA3, dentate gyrus, hilus), or in cortical regions involved in memory including the retrosplenial and perirhinal cortices (Supplementary Table 2). Thus, neuronal death and oxidative stress did not appear to contribute to acutely impaired memory function after seizures.

Figure 3. Acute memory deficits after seizures were not associated with neuronal cell death.

(A) Representative photomicrographs (20X) of Caspase 3 (Casp3; red) co-stained with NeuN (green) and DAPI (blue) in the CA1 region of the hippocampus from a healthy pregnant (Preg) rat that was either a no-seizure control or had seizures (+Seizures). White arrow heads point to Casp3+ cells within CA1 of both the no-seizure control rat and rat that had seizures. Scale bar is 100 μm. (B) Quantification of Casp3+ cells per area of CA1 in the hippocampus of Preg (left), experimental preeclampsia (ePE; middle) and virgin rats (right) shows Casp3 staining was similar between no-seizure controls and rats that had seizures in all groups. p > 0.05 by t-test. Error bars are SEM.

Seizures can disrupt hippocampal network dynamics by impairing synaptic plasticity independently of neuronal death that could contribute to impaired memory in Preg and ePE rats (Han et al., 2016). To investigate mechanisms by which memory was acutely impaired after seizures, hippocampal slice electrophysiology was performed to assess synaptic plasticity of the CA3 – CA1 Schaffer Collateral pathway. In slices from no-seizure controls, TBS resulted in LTP, increasing the fEPSP to ~ 150% of baseline that was maintained over time in Preg (Figure 4A), ePE (Figure 4B) and virgin rats (Figure 4C). In contrast, slices from Preg and ePE rats that had seizures had impaired LTP, with TBS increasing fEPSPs to only ~120% of baseline initially that degraded over time (Figure 4A and 4B). However, seizures in virgin rats had no effect on LTP that was robust, maintained over time and was similar to no-seizure controls (Figure 4C). Seizures impaired LTP in slices from Preg and ePE rats, but not virgin rats such that the fold-change in slope was significantly lower than no-seizure controls and virgin rats that had seizures (two-way ANOVA, F2, 30 = 3.63, p < 0.01; Figure 4D).

Figure 4. Seizures in pregnancy and ePE impair long-term potentiation (LTP) of hippocampal slices.

Evoked field excitatory post-synaptic potential (fEPSP) slopes in hippocampal slices from no-seizure controls (black) and rats that had seizures (red). After 20 min baseline recording (normalized to 100%), a brief theta burst stimulation (TBS) was delivered and fEPSP recorded for 60 min. Representative tracings show baseline fEPSP (1) and fEPSP after TBS (2). Scale bar is 5 mV / 5 ms. (A) TBS increased fEPSP slope compared to baseline in pregnant (Preg) controls that was decreased in Preg rats that had seizures. (B) fEPSP slope increased after TBS in slices from rats that had experimental preeclampsia (ePE) compared to baseline, and to a lesser extent in ePE rats that had eclampsia-like seizures. (C) TBS-induced increase in fEPSP slope in virgin rats was similar without and with seizures. (D) LTP was quantified by calculating the fold-change in fEPSP slope by comparing the last 10 min of recording (right boxed inset; 2) to the last 10 min of baseline (left boxed inset; 1). Seizures in Preg and ePE rats decreased potentiation compared to no-seizure control rats and virgin rats that had seizures, whereas potentiation was similar between virgin rats without and with seizures. Data analyzed using a two-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey test for multiple comparisons. There was a significant interaction between the effects of pregnancy status and seizures on LTP (n = 6 rats/group and 1 slice/rat, ** p < 0.01, F2, 30 = 3.63). Error bars represent SEM.

To determine whether seizures altered pre-synaptic function, we analyzed the paired-pulse ratio as a measure of pre-synaptic neurotransmitter release probability (Debanne et al., 1996; Sudhof, 2004). Paired-pulse ratios were similar between groups and unaffected by seizures (Supplementary Figure 5a), suggesting that changes in pre-synaptic glutamate release did not contribute to seizure-induced impairment of LTP. Further, to investigate the effect of seizures on CA3 axonal excitability, input-output curves of fEPSP slopes across the stimulus intensity range 0 – 60 μA were analyzed. Supplementary Figure 5b shows representative input-output curves of slices from Preg, ePE and virgin rats that were either no-seizure controls or had seizures. Input-output curves were similar between all groups of rats with and without seizures (Supplementary Figure 5b).

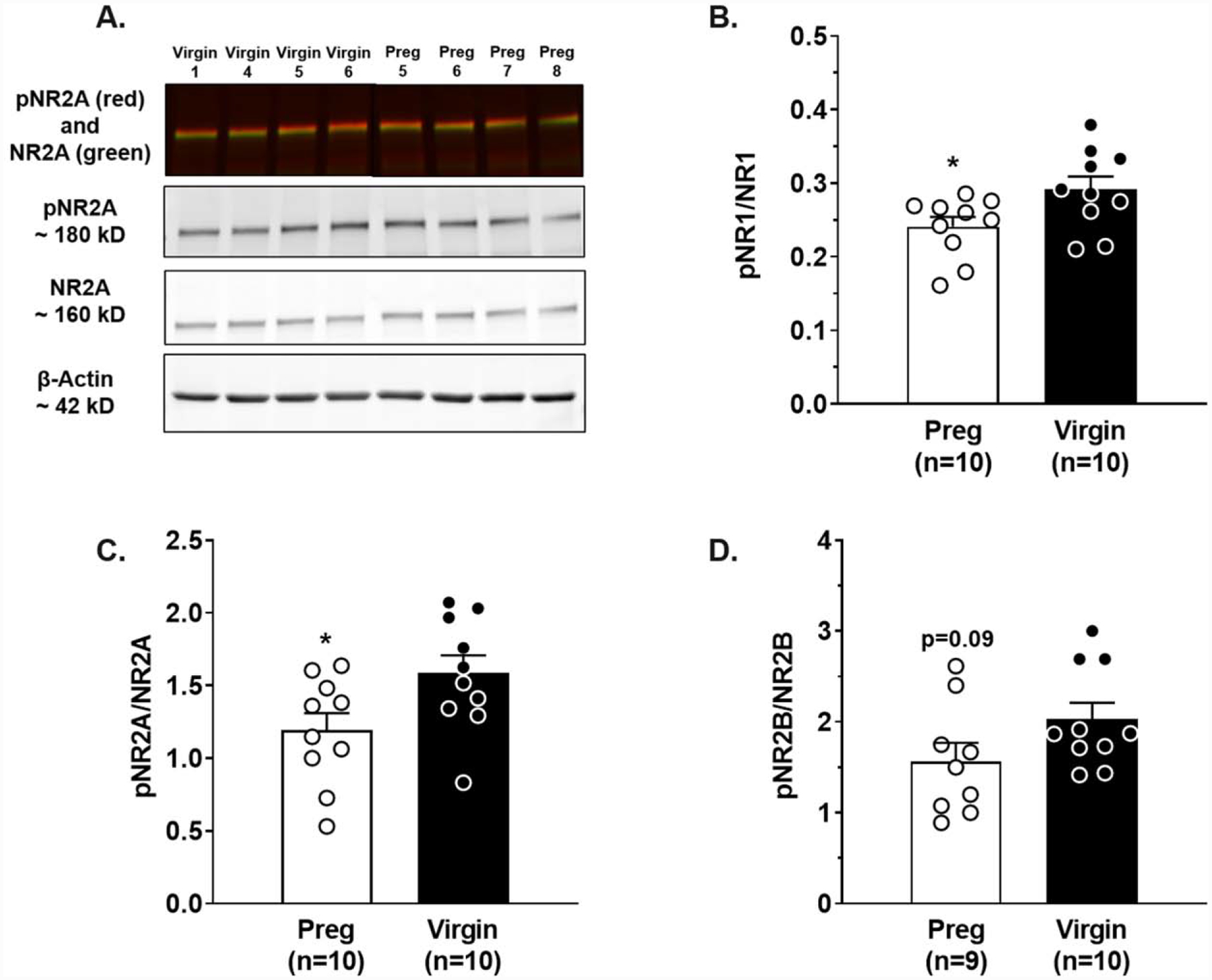

To investigate potential mechanisms by which pregnancy may predispose to hippocampal network dysfunction after status convulsions, Western blot was used to measure and compare total and phosphorylated hippocampal NMDAR protein expression of main NMDAR subunits NR1, NR2A and NR2B that are primarily involved in LTP as a measure of NMDAR activity. Figure 5A shows a representative blot of total NR2A and phosphorylated (p)NR2A in hippocampus from virgin and Preg rats (for full blots see Supplementary Figure 6). There were no differences in total NR1, NR2A or NR2B subunit protein expression between groups (Supplementary Figure 7). However, pregnancy decreased NR1 subunit activity (Student’s t-test, t18 = 2.335, p < 0.05; Figure 5B) and NR2A activity (Student’s t-test, t18 = 2.312, p < 0.05; Figure 5C), as indicated by a significant reduction in the ratio of phospho:total protein expression in hippocampus from Preg compared to virgin rats. NR2B subunit activity trended towards being lower in pregnancy (Student’s t-test, t18 = 1.745, p = 0.09; Figure 5D), but this did not reach statistical significance. Together these data suggest that seizures did not alter synaptic transmission or axonal excitability, but rather that changes in post-synaptic function contributed to impaired LTP and memory dysfunction that may be due to pregnancy-induced changes in NMDAR function.

Figure 5. Pregnancy-induced changes in hippocampal NMDAR subunit activity.

(A) Representative Western blot of NR2A subunit expression in the hippocampus of virgin (black) and pregnant (Preg; white) rats. Pregnancy decreased the ratio of phosphorylated(p):total protein expression of the (B) NR1 subunit and (C) NR2A subunit compared to virgin rats, but did not affect (D) NR2B subunit expression. Data analyzed using a Student’s t-test. *p<0.05 vs. Virgin. Error bars are SEM. The representative blots have been cropped to accurately represent the groups being compared. The full blots are available in the Supplementary Material.

Seizures during pregnancy and ePE cause long-lasting hippocampal dysfunction

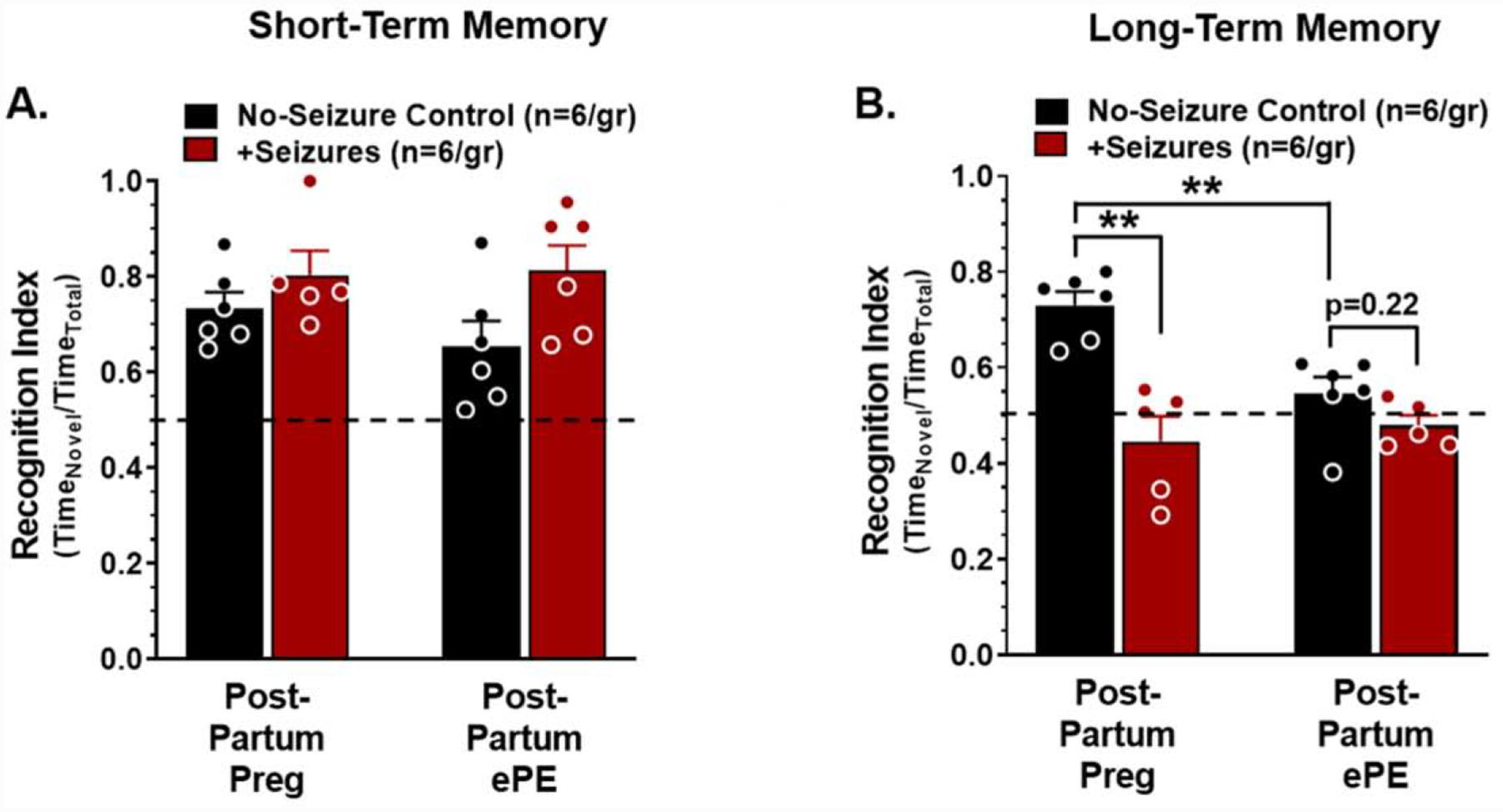

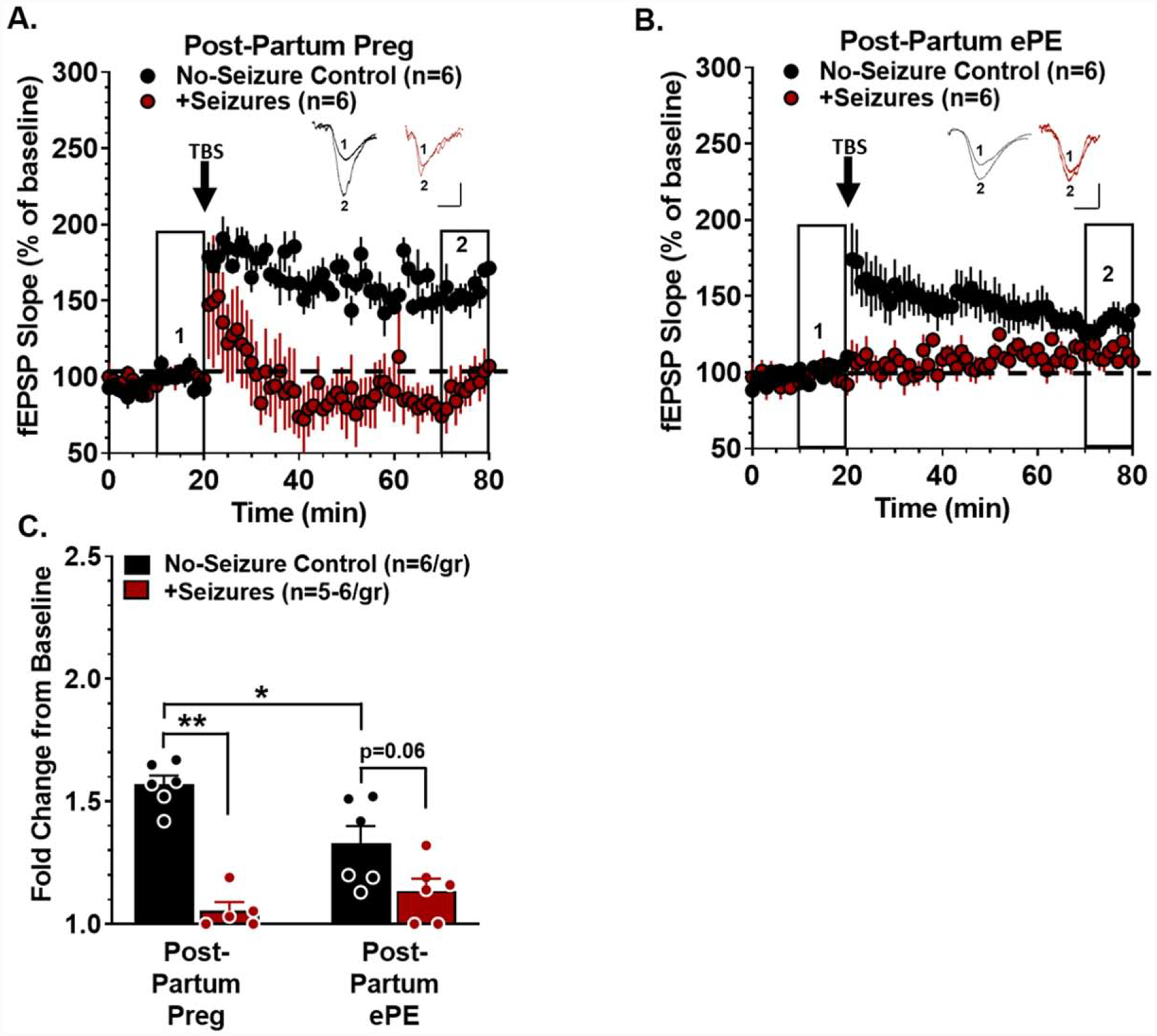

Women report memory impairment months to years after their pregnancy affected by preeclampsia/eclampsia that demonstrates long-lasting neurological consequences (Brusse et al., 2008; Fields et al., 2017; Shah et al., 2008). To determine if acute memory impairments occurring after seizures in Preg and ePE rats persisted in to the post-partum period, memory function and LTP were assessed 5 weeks after seizures. Figure 6 shows recognition index for STM and LTM assessments of post-partum rats that had a healthy pregnancy or post-partum rats that had pregnancy complicated by ePE with or without eclampsia-like seizures. There were no differences in STM function between groups (Figure 6A). In contrast, LTM was impaired in rats that had ePE compared to those that had a normal pregnancy, suggesting ePE alone had a deleterious effect on memory long after pregnancy (two-way ANOVA, F1, 18 = 9.469; p < 0.01; Figure 6B). In addition, seizures impaired LTM in rats that had a normal pregnancy, however, the impact of seizures on LTM in rats that had ePE was less clear because LTM in formerly ePE rats was already substantially impaired (Figure 6B). Figure 7 shows LTP of hippocampal slices 5 weeks after seizures in rats with normal pregnancy (Figure 7A) or pregnancy complicated by ePE (Figure 7B). LTP was impaired in rats that had ePE compared to those that had a normal pregnancy independently of seizures (Figure 7C). Seizures exacerbated hippocampal dysfunction and impaired LTP in both groups (two-way ANOVA, F1, 19 = 9.991, p < 0.01; Figure 7C). Impairment of LTP was not due to changes in pre-synaptic function, as evidenced by paired-pulse ratios being similar between groups (Supplementary Figure 8a) or changes in axonal excitability, as input-output curves were also similar between groups (Supplementary Figure 8b). Thus, ePE caused delayed hippocampal impairment resulting in persistently impaired LTP and memory. Further, seizure-induced STM dysfunction was transient; however, seizures caused long-lasting hippocampal post-synaptic dysfunction and impaired LTM well in to the post-partum period in both Preg and ePE rats.

Figure 6. Seizures in pregnancy and ePE causes long-lasting memory dysfunction.

A novel object recognition index was used to determine short- and long-term memory function five weeks after seizures. (A) Recognition indices of short-term memory were similar between rats that had a healthy pregnancy (Post-Partum Preg) and those that had pregnancy complicated by experimental preeclampsia (Post-Partum ePE) and were unaffected by seizures in either group (two-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey test, F1,19 = 0.881, p > 0.05). (B) Recognition indices of long-term memory were decreased in Post-Partum ePE rats without and with seizures compared to Post-Partum Preg rats. Seizures decreased long-term memory in Post-Partum Preg rats compared to no-seizure controls but did not affect long-term memory in Post-Partum ePE rats. Data were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA with a post-hoc Tukey test for multiple comparisons. There was a significant interaction between the effects of pregnancy status and seizures on long-term memory function (n = 6 rats/group, **p < 0.,01, F1,18 = 9.469). Error bars are SEM.

Figure 7. Hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP) is impaired weeks after eclampsia.

Five weeks after seizures, evoked field excitatory post-synaptic potential (fEPSP) slopes in hippocampal slices were measured from no-seizure controls (black) and rats that had seizures (red). After 20 min baseline recording (normalized to 100%), a brief theta burst stimulation (TBS) was delivered and fEPSP recorded for 60 min. Representative tracings show baseline fEPSP (1) and fEPSP after TBS (2). Scale bar is 5 mV / 5 ms. (A) TBS increased fEPSP slope in rats that had a normal pregnancy (Post-Partum Preg) that was decreased in Post-Partum Preg rats that had seizures. (B) fEPSP slope increased after TBS in rats that had pregnancy complicated by experimental preeclampsia (Post-Partum ePE) that declined over time and was abolished in rats that had eclampsia-like seizures. (C) LTP was quantified by calculating the fold-change in fEPSP slope by comparing the last 10 min of recording (right boxed inset; 2) to the last 10 min of baseline (left boxed inset; 1). LTP was decreased in Post-Partum ePE rats compared to Post-Partum Preg rats, and seizures exacerbated impairment in both groups. Data were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey test for multiple comparisons. There was a significant interaction between the effect of pregnancy status and seizures on LTP (n = 6 rats/group and 1 slice/rat, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, F1, 19 = 9.991). Error bars represent SEM.

Discussion

Age-related cognitive decline and memory deficits affect the majority of people over the age of 70, many of which are due to hippocampal involvement (Driscoll et al., 2003; Harada et al., 2013). However, women who had preeclampsia/eclampsia have cognitive impairment similar to that associated with normal aging at nearly half that age (Andersgaard et al., 2009; Aukes et al., 2007; Postma et al., 2016; Shah et al., 2008). Here, we show that ePE had a deleterious effect on hippocampal function independently of seizures, with neuronal network plasticity and memory function deteriorating over time post-pregnancy. This is the first study that we are aware of to provide evidence of a model of ePE that seems to mimics the cognitive decline associated with preeclampsia later in life, and represents a useful tool to study mechanisms by which preeclampsia may cause memory dysfunction. Further, seizures in pregnancy and ePE caused acute and long-lasting memory impairment that was associated with persistent changes in post-synaptic hippocampal network function but not overt neuronal death. Interestingly, seizure-induced impairment of memory and LTP did not occur in virgin rats, and was similar between Preg and ePE rats, suggesting that the pregnant state increased the susceptibility of the hippocampus to seizure-induced dysfunction. These findings highlight the importance of early detection and effective management of preeclampsia in preventing preeclampsia-induced cognitive decline as well as the importance of seizure prevention in pregnancy and preeclampsia. Further, this study reveals the therapeutic potential of targeting hippocampal neuronal plasticity and network function to prevent permanent dysfunction in the setting of preeclampsia and unavoidable eclampsia.

Preeclampsia is a vascular disease with no true cure (Townsend et al., 2016). Cerebrovascular dysfunction persists years after preeclampsia and is thought to be a primary contributor to increased incidence of cerebral white matter lesions and decreased cortical grey matter later in life in women with a history of preeclampsia (Amaral et al., 2015; Siepmann et al., 2017). White matter lesions and cortical atrophy are known contributors to cognitive decline and are an early indicator of dementia (Bilello et al., 2015). In the current study, we present a model of ePE that demonstrates early-onset memory dysfunction due to persistent, and potentially permanently impaired synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. Importantly, this model of ePE also has cerebrovascular dysfunction in both cortical arterioles supplying white matter tracts as well as hippocampal arterioles critical to perfusion of the hippocampus (Johnson and Cipolla, 2016, 2018). We previously found that hippocampal arterioles were smaller and stiffer with limited vasodilatory capacity in ePE compared to the normal pregnant and virgin states that may represent a mechanism by which ePE caused delayed cognitive decline in the current study (Johnson and Cipolla, 2016). If hippocampal vascular dysfunction persists in to the post-partum period, hippocampal hypoperfusion and/or neurovascular uncoupling could occur, resulting in neuronal network dysfunction and memory impairment (Gorelick et al., 2011; Iadecola, 2013). However, the contribution of hippocampal vascular dysfunction to prolonged LTP impairment after ePE requires further investigation. While it is unclear from the current study whether structural changes in cortical grey and white matter contribute to memory impairment, our findings suggest impaired hippocampal neuronal plasticity, a critical mechanism of memory, contributes to impaired memory function after ePE.

Seizures impaired hippocampal synaptic plasticity similarly in pregnancy and ePE that did not occur after seizures in virgin rats. This suggests it is pregnancy that increases the susceptibility of hippocampal postsynaptic neurons to damage during seizures. The basis of learning and memory lies within the ability of hippocampal neurons to rapidly modulate synaptic transmission to strengthen or weaken neuronal networks (Lynch, 2004). Disruption of such hippocampal plasticity, including LTP of the Schaffer Collateral pathway, is well known to contribute to learning and memory dysfunction (Abraham et al., 2019; Lynch, 2004). LTP is activity-driven long-lasting increases in the efficacy of excitatory synaptic transmission, and is considered the underlying cellular mechanism of learning and memory (Abraham et al., 2019). LTP of the Schaffer Collateral pathway is largely NMDAR-dependent that has been shown to be impaired after seizures (Abraham et al., 2019; Luscher and Malenka, 2012; Zhou et al., 2007). In a study using PTZ to induce status epilepticus in young rats, LTP in the Schaffer Collateral pathway was impaired 24 hr after seizures due to increased postsynaptic expression of NMDARs (Postnikova et al., 2017). Studies using other seizure models (e.g. fluorothyl, lithium-pilocarpine) have shown similar findings (Naylor et al., 2013; Reid and Stewart, 1997). Therefore, seizures have been proposed to cause an indiscriminate and wide-spread induction of LTP due to increased surface NMDAR expression that reduces the potential and ability for additional induction of LTP (Ben-Ari and Gho, 1988; Reid and Stewart, 1997; Zhou et al., 2007). Interestingly, status convulsions had no effect on hippocampal function in female, virgin rats in the current study that may be due to female sex steroids at normal cycling levels being neuroprotective against disruption of hippocampal LTP. Hippocampal-derived neurosteroids in female rodents modulate synaptic plasticity and have been reported to be responsible for cognitive resilience after chronic stress only in females (Fester and Rune, 2015; Hojo et al., 2011; Hojo and Kawato, 2018; Luine, 2016) that could also explain the lack of seizure-induced impairment of hippocampal network plasticity and memory in virgin rats in the current study. Further, it is possible that Preg and ePE rats had more severe electrographic seizures than virgin rats that could contribute to the pregnancy-specific deficits. Regardless, seizures of similar duration and severity as assessed behaviorally caused hippocampal dysfunction in Preg and ePE rats that did not occur in the virgin state. Thus, while Preg and ePE rats are also female, changes associated with pregnancy appear to increase the susceptibility of the hippocampus to seizure-induced dysfunction.

Pregnancy is a state that undergoes tremendous physiological adaptation, including in the hippocampus that could increase the sensitivity to seizure-induced impairment of LTP due to changes in NMDAR function (Maguire et al., 2009; Maguire and Mody, 2008). NMDARs in CA3-CA1 synapses are primarily composed of NR1-NR2A or NR1-NR2B containing subunits, and the role of each in hippocampal LTP is controversial. Several studies have shown that NMDARs containing the NR2B, but not NR2A subunits are primarily responsible for induction of LTP in the Schaffer Collateral pathway of the hippocampus (Bartlett et al., 2007; Clayton et al., 2002; Foster et al., 2010; Gardoni et al., 2006). In contrast, others have shown LTP is dependent upon NMDAR containing NR2A, but not NR2B subunits (Liu et al., 2004). Alternatively, the concept has emerged that it is the appropriate balance of NR2A subunit-containing and NR2B subunit-containing NMDARs at hippocampal synapses that is crucial for induction of LTP (Bellone and Nicoll, 2007; Costa et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2004; MacDonald et al., 2006). In the current study, we found that normal pregnancy decreased NMDAR activity in the hippocampus compared to the virgin state by decreasing the phospho:total NR2A and NR1 subunit expression, without significantly affecting NR2B subunit-containing receptors. In support of this, a previous study reported that NMDAR binding was decreased in the hippocampus late in pregnancy in rats, as measured using autoradiography (Standley, 1999). Interestingly, these pregnancy-induced changes in hippocampal NMDAR activity did not affect basal network plasticity, as there were no differences in LTP between no-seizure controls from any group in the current study. However, such changes in NMDAR function during pregnancy could represent an underlying mechanism by which pregnancy predisposes the hippocampus to seizure-induced network dysfunction that results in acute and prolonged impairment of LTP.

Seizure-induced neuronal injury depends largely upon seizure severity and duration, as well as seizure type that varies with different chemoconvulsants (Dingledine et al., 2014; Kandratavicius et al., 2014). From clinical and experimental studies of epilepsy, it is accepted that relatively short tonic-clonic seizures do not cause neuronal death, however, prolonged and recurrent seizures (30 min of seizure activity), such as induced in the current study, can cause permanent neuronal injury and cognitive deficits (Dingledine et al., 2014). The findings in the current study are in partial agreement with previous studies, with a single tonic-clonic seizure causing no neuronal injury or memory impairment in any group investigated. Surprisingly, prolonged and recurrent seizures resulted in impaired hippocampal plasticity and memory dysfunction in pregnancy and ePE that was not due to neuronal death. In contrast to these current findings, other rat models of preeclampsia report PTZ-induced hippocampal CA1 and CA3 neuronal loss acutely (days) after PTZ-induced seizures (Li et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019; Oliveira et al., 2019). These contradicting findings could be due to the different rodent models of preeclampsia being used in these previous studies that include an endotoxin-induced (e.g. lipopolysaccharide infusion) model of hypertension during pregnancy or surgical clamping of a renal artery to elevate blood pressure in pregnancy (Li et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019; Oliveira et al., 2019). In addition, different seizure paradigms could further contribute to the contradicting findings of seizure-induced hippocampal neuronal death. In the current study, we induced multiple tonic-clonic seizures on a single day late in gestation to model the isolated nature of eclampsia and avoid any potential kindling that could cause epileptogenesis and confound long-term studies. However, other studies modeled eclampsia by injecting PTZ on several consecutive days towards the end of pregnancy (Li et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019; Oliveira et al., 2019). The multiple days of seizures in combination with the different models could explain why previous studies demonstrated hippocampal neuronal loss that was not evident in the current study. Alternatively, it is possible that delayed neuronal death occurred that was not detected in the current study due to the single time point assessed after seizures that could contribute to impaired LTP and memory post-partum. Regardless, while there was no acute evidence of neuronal loss after seizures, there was robust and persistent impairment of hippocampal network plasticity that likely contributed to long-lasting memory dysfunction.

In conclusion, we provide evidence of a model of early-onset cognitive decline after pregnancies complicated by ePE. Further, seizures during pregnancy and ePE caused hippocampal dysfunction, including impaired neuroplasticity and memory. The availability of models that mimic aspects of the long-lasting cerebrovascular and neuronal consequences of preeclampsia and eclampsia provides a powerful tool to better understand these pathological processes. Clinical studies have shown preeclampsia and eclampsia are associated with increased white matter lesion burden and cortical atrophy that is thought to contribute to the memory and cognitive dysfunction in women later in life. However, the findings of the current study suggest disrupted hippocampal neuroplasticity as an alternative, or additional mechanism by which cognition may be affected after preeclampsia and seizures during pregnancy. Such “silent” brain injury would likely be undetectable in women on MRI, but could explain, at least in part, predominant and long-lasting memory dysfunction reported to occur in women after eclampsia as was presented in the current case report (Brusse et al., 2008; Fields et al., 2017; Postma et al., 2014; Postma et al., 2013). Further, the lack of acute neuronal death after seizures highlights the potential of reversing seizure-induced memory dysfunction by developing therapeutic targets to restore neuronal plasticity in the hippocampus to relieve the cognitive burden in these young mothers.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Preeclampsia (PE) and eclampsia are associated with cognitive decline later in life

How the cognition-centric hippocampus is affected by PE/eclampsia remains unclear

Delayed memory decline occurred in experimental PE rats via impaired neuroplasticity

Eclamptic seizures caused acute and long-lasting hippocampal network dysfunction

Acknowledgements

We thank Nicole DeLance of the Microscopy Imaging Center at the University of Vermont for her technical expertise in performing histology and confocal microscopy. We thank Sarah Tremble in the Dept. of Neurological Sciences at the University of Vermont for her technical expertise in performing Western blot. We also thank Dr. Joe Brayden of the Dept. of Pharmacology at the University of Vermont for his technical expertise in electrophysiology and for the use of electrophysiology equipment.

Funding

This work was supported by the NIH National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke R01 NS045940 (MJC) and R01 NS108455 (MJC), the Preeclampsia Foundation, the Totman Medical Research Trust and the Cardiovascular Research Institute of Vermont. The Microscopy Imaging Center at the University of Vermont was supported by NIH 1S10RR019246 from the National Center for Research Resources.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- EEG

electroencephalogram

- ePE

experimental preeclampsia

- fEPSP

field excitatory post-synaptic potentials

- GABA

gamma-aminobutyric acid

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- LTM

long-term memory

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- MgSO4

magnesium sulfate

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- NOR

novel object recognition

- Preg

pregnant

- PTZ

pentylenetetrazole

- RIP3

receptor-interacting protein 3

- STM

short-term memory

- TBS

theta burst stimulation

- 3-NT

3-nitrotyrisine

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of interest: none

References

- Abraham WC, Jones OD, Glanzman DL, 2019. Is plasticity of synapses the mechanism of long-term memory storage? NPJ Sci Learn 4, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral LM, Cunningham MW Jr., Cornelius DC, LaMarca B, 2015. Preeclampsia: long-term consequences for vascular health. Vasc Health Risk Manag 11, 403–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersgaard AB, Herbst A, Johansen M, Borgstrom A, Bille AG, Oian P, 2009. Follow-up interviews after eclampsia. Gynecol Obstet Invest 67, 49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aukes AM, De Groot JC, Wiegman MJ, Aarnoudse JG, Sanwikarja GS, Zeeman GG, 2012. Long-term cerebral imaging after pre-eclampsia. BJOG 119, 1117–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aukes AM, Wessel I, Dubois AM, Aarnoudse JG, Zeeman GG, 2007. Self-reported cognitive functioning in formerly eclamptic women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 197, 365 e361–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett TE, Bannister NJ, Collett VJ, Dargan SL, Massey PV, Bortolotto ZA, Fitzjohn SM, Bashir ZI, Collingridge GL, Lodge D, 2007. Differential roles of NR2A and NR2B-containing NMDA receptors in LTP and LTD in the CA1 region of two-week old rat hippocampus. Neuropharmacology 52, 60–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellone C, Nicoll RA, 2007. Rapid bidirectional switching of synaptic NMDA receptors. Neuron 55, 779–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y, Gho M, 1988. Long-lasting modification of the synaptic properties of rat CA3 hippocampal neurones induced by kainic acid. J Physiol 404, 365–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilello M, Doshi J, Nabavizadeh SA, Toledo JB, Erus G, Xie SX, Trojanowski JQ, Han X, Davatzikos C, 2015. Correlating Cognitive Decline with White Matter Lesion and Brain Atrophy Magnetic Resonance Imaging Measurements in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis 48, 987–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent NJ, Gaskin S, Squire LR, Clark RE, 2010. Object recognition memory and the rodent hippocampus. Learn Mem 17, 5–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusse I, Duvekot J, Jongerling J, Steegers E, De Koning I, 2008. Impaired maternal cognitive functioning after pregnancies complicated by severe pre-eclampsia: a pilot case-control study. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica 87, 408–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherian A, Thomas SV, 2009. Status epilepticus. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 12, 140–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton DA, Mesches MH, Alvarez E, Bickford PC, Browning MD, 2002. A hippocampal NR2B deficit can mimic age-related changes in long-term potentiation and spatial learning in the Fischer 344 rat. J Neurosci 22, 3628–3637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa C, Sgobio C, Siliquini S, Tozzi A, Tantucci M, Ghiglieri V, Di Filippo M, Pendolino V, de Iure A, Marti M, Morari M, Spillantini MG, Latagliata EC, Pascucci T, Puglisi-Allegra S, Gardoni F, Di Luca M, Picconi B, Calabresi P, 2012. Mechanisms underlying the impairment of hippocampal long-term potentiation and memory in experimental Parkinson’s disease. Brain 135, 1884–1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidge ST, de Groot CJ, Taylor RN 2014. Endothelial Cell Dysfunction. In: Chesley’s Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. pp. 181–207. Eds. Taylor RN, Roberts JM, Cunningham FG, Lindheimer MD. Academic Press/Elsevier: Boston. [Google Scholar]

- Dayan N, Kaur A, Elharram M, Rossi AM, Pilote L, 2018. Impact of Preeclampsia on Long-Term Cognitive Function. Hypertension 72, 1374–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debanne D, Guerineau NC, Gahwiler BH, Thompson SM, 1996. Paired-pulse facilitation and depression at unitary synapses in rat hippocampus: quantal fluctuation affects subsequent release. J Physiol 491 (Pt 1), 163–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingledine R, Varvel NH, Dudek FE, 2014. When and how do seizures kill neurons, and is cell death relevant to epileptogenesis? Adv Exp Med Biol 813, 109–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas KA, Redman CW, 1994. Eclampsia in the United Kingdom. BMJ 309, 1395–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll I, Hamilton DA, Petropoulos H, Yeo RA, Brooks WM, Baumgartner RN, Sutherland RJ, 2003. The aging hippocampus: cognitive, biochemical and structural findings. Cereb Cortex 13, 1344–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elharram M, Dayan N, Kaur A, Landry T, Pilote L, 2018. Long-Term Cognitive Impairment After Preeclampsia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 132, 355–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fester L, Rune GM, 2015. Sexual neurosteroids and synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. Brain Res 1621, 162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields JA, Garovic VD, Mielke MM, Kantarci K, Jayachandran M, White WM, Butts AM, Graff-Radford J, Lahr BD, Bailey KR, Miller VM, 2017. Preeclampsia and cognitive impairment later in life. Am J Obstet Gynecol 217, 74 e71–74 e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster KA, McLaughlin N, Edbauer D, Phillips M, Bolton A, Constantine-Paton M, Sheng M, 2010. Distinct roles of NR2A and NR2B cytoplasmic tails in long-term potentiation. J Neurosci 30, 2676–2685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardoni F, Picconi B, Ghiglieri V, Polli F, Bagetta V, Bernardi G, Cattabeni F, Di Luca M, Calabresi P, 2006. A critical interaction between NR2B and MAGUK in L-DOPA induced dyskinesia. J Neurosci 26, 2914–2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, Decarli C, Greenberg SM, Iadecola C, Launer LJ, Laurent S, Lopez OL, Nyenhuis D, Petersen RC, Schneider JA, Tzourio C, Arnett DK, Bennett DA, Chui HC, Higashida RT, Lindquist R, Nilsson PM, Roman GC, Sellke FW, Seshadri S, American Heart Association Stroke Council, C.o.E., Prevention, C.o.C.N.C.o.C.R., Intervention, Council on Cardiovascular, S., Anesthesia, 2011. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke 42, 2672–2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger JP, Alexander BT, Llinas MT, Bennett WA, Khalil RA, 2001. Pathophysiology of hypertension during preeclampsia linking placental ischemia with endothelial dysfunction. Hypertension 38, 718–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han T, Qin Y, Mou C, Wang M, Jiang M, Liu B, 2016. Seizure induced synaptic plasticity alteration in hippocampus is mediated by IL-1beta receptor through PI3K/Akt pathway. Am J Transl Res 8, 4499–4509. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada CN, Natelson Love MC, Triebel KL, 2013. Normal cognitive aging. Clin Geriatr Med 29, 737–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hojo Y, Higo S, Kawato S, Hatanaka Y, Ooishi Y, Murakami G, Ishii H, Komatsuzaki Y, Ogiue-Ikeda M, Mukai H, Kimoto T, 2011. Hippocampal synthesis of sex steroids and corticosteroids: essential for modulation of synaptic plasticity. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2, 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hojo Y, Kawato S, 2018. Neurosteroids in Adult Hippocampus of Male and Female Rodents: Biosynthesis and Actions of Sex Steroids. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 9, 183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C, 2013. The pathobiology of vascular dementia. Neuron 80, 844–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AC, Cipolla MJ, 2016. Altered hippocampal arteriole structure and function in a rat model of preeclampsia: Potential role in impaired seizure-induced hyperemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 271678X16676287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AC, Cipolla MJ, 2018. Impaired function of cerebral parenchymal arterioles in experimental preeclampsia. Microvascular research 119, 64–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AC, Miller JE, Cipolla MJ, 2019. Memory impairment in spontaneously hypertensive rats is associated with hippocampal hypoperfusion and hippocampal vascular dysfunction. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 271678X19848510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AC, Nagle KJ, Tremble SM, Cipolla MJ, 2015. The Contribution of Normal Pregnancy to Eclampsia. PloS one 10, e0133953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AC, Tremble SM, Chan SL, Moseley J, LaMarca B, Nagle KJ, Cipolla MJ, 2014. Magnesium sulfate treatment reverses seizure susceptibility and decreases neuroinflammation in a rat model of severe preeclampsia. PloS one 9, e113670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandratavicius L, Balista PA, Lopes-Aguiar C, Ruggiero RN, Umeoka EH, Garcia-Cairasco N, Bueno-Junior LS, Leite JP, 2014. Animal models of epilepsy: use and limitations. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 10, 1693–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamarca B, 2012. Endothelial dysfunction. An important mediator in the pathophysiology of hypertension during pre-eclampsia. Minerva Ginecol 64, 309–320. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Han X, Yang J, Bao J, Di X, Zhang G, Liu H, 2017. Magnesium Sulfate Provides Neuroprotection in Eclampsia-Like Seizure Model by Ameliorating Neuroinflammation and Brain Edema. Mol Neurobiol 54, 7938–7948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Liu H, Yang Y, 2019. Magnesium sulfate attenuates brain edema by lowering AQP4 expression and inhibits glia-mediated neuroinflammation in a rodent model of eclampsia. Behav Brain Res 364, 403–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindheimer MD, Roberts JM, Cunningham FG, Chesley LC, 2009. Chesley’s hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. Academic Press/Elsevier: Amsterdam; Boston. [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Wong TP, Pozza MF, Lingenhoehl K, Wang Y, Sheng M, Auberson YP, Wang YT, 2004. Role of NMDA receptor subtypes in governing the direction of hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Science 304, 1021–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luine V, 2016. Estradiol: Mediator of memories, spine density and cognitive resilience to stress in female rodents. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology 160, 189–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luscher C, Malenka RC, 2012. NMDA receptor-dependent long-term potentiation and long-term depression (LTP/LTD). Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttjohann A, Fabene PF, van Luijtelaar G, 2009. A revised Racine’s scale for PTZ-induced seizures in rats. Physiol Behav 98, 579–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch MA, 2004. Long-term potentiation and memory. Physiol Rev 84, 87–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald JF, Jackson MF, Beazely MA, 2006. Hippocampal long-term synaptic plasticity and signal amplification of NMDA receptors. Critical reviews in neurobiology 18, 71–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKay AP, Berg CJ, Atrash HK, 2001. Pregnancy-related mortality from preeclampsia and eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 97, 533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire J, Ferando I, Simonsen C, Mody I, 2009. Excitability changes related to GABAA receptor plasticity during pregnancy. J Neurosci 29, 9592–9601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire J, Mody I, 2008. GABA(A)R plasticity during pregnancy: relevance to postpartum depression. Neuron 59, 207–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EC, Boehme AK, Chung NT, Wang SS, Lacey JV Jr., Lakshminarayan K, Zhong C, Woo D, Bello NA, Wapner R, Elkind MSV, Willey JZ, 2019. Aspirin reduces long-term stroke risk in women with prior hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Neurology 92, e305–e316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myatt L, 2002. Role of placenta in preeclampsia. Endocrine 19, 103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor DE, Liu H, Niquet J, Wasterlain CG, 2013. Rapid surface accumulation of NMDA receptors increases glutamatergic excitation during status epilepticus. Neurobiol Dis 54, 225–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira LF, Pinheiro D, Rodrigues LD, Reyes-Garcia SZ, Nishi EE, Ormanji MS, Faber J, Cavalheiro EA, 2019. Behavioral, electrophysiological and neuropathological characteristics of the occurrence of hypertension in pregnant rats. Sci Rep 9, 4051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orfila JE, Grewal H, Dietz RM, Strnad F, Shimizu T, Moreno M, Schroeder C, Yonchek J, Rodgers KM, Dingman A, Bernard TJ, Quillinan N, Macklin WB, Traystman RJ, Herson PS, 2017. Delayed inhibition of tonic inhibition enhances functional recovery following experimental ischemic stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 271678X17750761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postma IR, Bouma A, Ankersmit IF, Zeeman GG, 2014. Neurocognitive functioning following preeclampsia and eclampsia: a long-term follow-up study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 211, 37 e31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postma IR, Bouma A, de Groot JC, Aukes AM, Aarnoudse JG, Zeeman GG, 2016. Cerebral white matter lesions, subjective cognitive failures, and objective neurocognitive functioning: A follow-up study in women after hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 38, 585–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postma IR, Groen H, Easterling TR, Tsigas EZ, Wilson ML, Porcel J, Zeeman GG, 2013. The brain study: Cognition, quality of life and social functioning following preeclampsia; An observational study. Pregnancy Hypertens 3, 227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postnikova TY, Zubareva OE, Kovalenko AA, Kim KK, Magazanik LG, Zaitsev AV, 2017. Status Epilepticus Impairs Synaptic Plasticity in Rat Hippocampus and Is Followed by Changes in Expression of NMDA Receptors. Biochemistry (Mosc) 82, 282–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid IC, Stewart CA, 1997. Seizures, memory and synaptic plasticity. Seizure 6, 351–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb AO, Mills NL, Din JN, Smith IB, Paterson F, Newby DE, Denison FC, 2009. Influence of the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and preeclampsia on arterial stiffness. Hypertension 53, 952–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankaralingam S, Xu Y, Sawamura T, Davidge ST, 2009. Increased lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 expression in the maternal vasculature of women with preeclampsia: role for peroxynitrite. Hypertension 53, 270–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreurs MP, Cipolla MJ, 2013. Pregnancy enhances the effects of hypercholesterolemia on posterior cerebral arteries. Reprod Sci 20, 391–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreurs MP, Hubel CA, Bernstein IM, Jeyabalan A, Cipolla MJ, 2013. Increased oxidized low-density lipoprotein causes blood-brain barrier disruption in early-onset preeclampsia through LOX-1. FASEB J 27, 1254–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah AK, Rajamani K, Whitty JE, 2008. Eclampsia: a neurological perspective. J Neurol Sci 271, 158–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siepmann T, Boardman H, Bilderbeck A, Griffanti L, Kenworthy Y, Zwager C, McKean D, Francis J, Neubauer S, Yu GZ, Lewandowski AJ, Sverrisdottir YB, Leeson P, 2017. Long-term cerebral white and gray matter changes after preeclampsia. Neurology 88, 1256–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standley CA, 1999. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor binding is altered and seizure potential reduced in pregnant rats. Brain Res 844, 10–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steegers EA, von Dadelszen P, Duvekot JJ, Pijnenborg R, 2010. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet 376, 631–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhof TC, 2004. The synaptic vesicle cycle. Annu Rev Neurosci 27, 509–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend R, O’Brien P, Khalil A, 2016. Current best practice in the management of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. Integr Blood Press Control 9, 79–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdes G, 2017. Preeclampsia and cardiovascular disease: interconnected paths that enable detection of the subclinical stages of obstetric and cardiovascular diseases. Integr Blood Press Control 10, 17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou JL, Shatskikh TN, Liu X, Holmes GL, 2007. Impaired single cell firing and long-term potentiation parallels memory impairment following recurrent seizures. Eur J Neurosci 25, 3667–3677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.