Abstract

CAR T-cell therapy has had limited success in early-phase clinical studies for solid tumors. Lack of efficacy is most likely multifactorial, including a limited array of targetable antigens. We reasoned that targeting the cancer-specific extra domain B (EDB) splice variant of fibronectin might overcome this limitation because it is abundantly secreted by cancer cells and adheres to their cell surface. In vitro, EDB-CAR T cells recognized and killed EDB-positive tumor cells. In vivo, 1×106 EDB-CAR T cells had potent antitumor activity in both subcutaneous and systemic tumor xenograft models, resulting in a significant survival advantage in comparison to control mice. EDB-CAR T cells also targeted the tumor vasculature, as judged by immunohistochemistry and imaging, and their anti-vascular activity was dependent on the secretion of EDB by tumor cells. Thus, targeting tumor-specific splice variants such as EDB with CAR T cells is feasible and has the potential to improve the efficacy of CAR T-cell therapy.

Keywords: T-cell immunotherapy, cancer, solid tumors, chimer antigen receptor, CAR, fibronectin, splice variant, tumor vasculature

INTRODUCTION

Genetically modified T cells expressing chimeric antigen receptors (CAR T cells) have potent antitumor activity in patients with B-cell lineage malignancies targeting CD19, CD22, CD30, and/or BCMA (1–3). However, CAR T cells so far have had limited antitumor activity in early-phase clinical studies for patients with solid tumors and brain tumors (4,5). This lack of efficacy is most likely multifactorial, including a limited array of targetable antigens, heterogenous antigen expression, and the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (4,6).

The majority of tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) that have been targeted with CAR T cells are differentially expressed cell surface molecules (6,7). However, tumor cells secrete extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules that adhere to their cell surface and thus could serve as CAR targets. One prominent molecule of the ECM is fibronectin, a ubiquitously expressed protein. However, tumor cells secrete oncofetal splice variants, which are not expressed in normal adult tissues (8). One of these, extra domain B fibronectin (EDB or EIIIB), has been studied extensively (9). It is expressed in a broad range of solid tumors, including lung, breast, and prostate cancers, and high-grade glioma making it a pan-cancer TAA (10,11). Expression in endothelial cells of the tumor vasculature has been described (12). EDB belongs to fibronectins that are only present in the ECM and is not present in so-called plasma fibronectin. Like other ECM family fibronectins, it binds integrins on the cell surface through RGD motifs (12). Antibody-drug conjugates, based on the high-affinity EDB-specific monoclonal antibody (mAb) L19 (13), have shown potent antitumor activity in preclinical animal models (14,15), and early-phase clinical testing is in progress. L19 mAb-based conjugates have been utilized successfully to image tumors in adult patients (16,17).

To investigate the ability of EDB-CAR T cells to directly target cancer cells and endothelial cells of the tumor vasculature, we generated T cells expressing an EDB-CAR based on the L19 mAb. We demonstrated that EDB-CAR T cells recognized and killed EDB-positive tumor cells in an antigen-dependent manner in vitro and had potent antitumor activity in three xenograft mouse models without apparent ‘on-target/off-cancer’ toxicity. EDB secretion by tumor cells enabled EDB-CAR T cells to target endothelial cells of the tumor vasculature. Thus, targeting proteins of the ECM, like EBD, have the potential to improve current CAR T-cell therapy for a broad range of solid tumors in which EDB is expressed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tumor cell lines

The U87 (glioma), A549 (lung cancer), A673 (Ewing sarcoma), 293T and HUVEC cell lines were purchased from the American Type Tissue Collection (ATCC). The lung metastatic osteosarcoma cell line LM7 was kindly provided by Dr. Eugenie Kleinerman (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX) in 2011. Primary fibroblast cell lines were previously established (18). The generation of the A549 cell line expressing an enhanced green fluorescence protein firefly luciferase fusion gene (GFP.ffluc) was previously described (4). All cell lines were grown in DMEM or RPMI (GE Healthcare Life Sciences HyClone Laboratories) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; GE Healthcare Life Sciences HyClone) and 2 mM Glutamax (Invitrogen) for 1–3 passages post thaw. HUVEC cells were cultured 2 passages post thaw using vascular basal media (ATCC) supplemented with components of the endothelial cell growth kit (ATCC). The U87 fibronectin knockout (KO) cell line (U87FN−/−) was generated by the Center for Advanced Genome Engineering (CAGE) at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (St. Jude) using CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing technology. Briefly, 400,000 U87 cells were transiently transfected with pre-complexed ribonuclear proteins (RNPs) consisting of 150 pmol of chemically modified sgRNA (5’ – CCUAUAGAAUUGGAGACACC- 3’, Synthego) and 35 pmol of Cas9 protein (St. Jude Protein Production Core) via nucleofection (Lonza, 4D-Nucleofector™ X-unit). Two clones were identified via targeted deep-sequencing using gene-specific primers with partial Illumina adapter overhangs (hFN1.F - 5’ CTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTagtgtaataccttgcagcaccagagc 3’, overhangs shown in upper case, hFN1.R – 5’ CAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTtcttgacctgcttccccatttcccg 3’, overhangs shown in upper case). Next-generation sequencing (NGS) analysis of clones was performed using CRIS.py (available on GitHub: https://github.com/patrickc01/CRIS.py). (19). Two hFN1 knockout clones were identified. The genotype of both clones is indicated below and shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. We selected 2H3 for our experiments. Cell lines were authenticated using the ATCC’s human STR profiling cell authentication service and routinely checked for Mycoplasma by the MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza).

Generation of retroviral vectors

The generation of the SFG retroviral vectors encoding the EphA2-CAR with a CD28 costimulatory domain, or GFP.ffluc, has been previously described (20). In-fusion cloning (Takara Bio) was used to generate the EDB-CAR with a CD28 costimulatory domain and a nonfunctional EDB-CAR with mutated immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs)(mutEDB-CAR) using our retroviral vector as a template, which encodes a EphA2-CAR.CD28ζ expression cassette, a 2A sequence, and truncated CD19 (20). The amino acid sequence of the EDB-CAR and mutEDB-CAR is shown in Supplementary Fig. S2. The EDB-specific single-chain variable fragment (scFv) was derived from the human mAb L19 (13) and synthesized by GeneArt (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RD114-pseudotyped retroviral particles were generated by transient transfection of 293T cells as previously described (20).

Generation of CAR T cells

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained from 11 healthy donors under an IRB-approved protocol at St. Jude. To generate CAR T cells, we used our previously described protocol (4). Briefly, 1 × 106 PBMCs were stimulated on non-tissue culture treated 24-well plates (Corning), which were pre-coated with anti-CD3 (0.1 mg/mL) and anti-CD28 (0.1 mg/mL)(BD). Recombinant human IL7 and IL15 (IL7: 10 ng/mL; IL15: 5 ng/mL; PeproTech) were added to cultures the next day. On day 2, T cells were transduced with 0.5 mL retroviral particle supernatant on RetroNectin (10 mg/well) (Clontech)-coated plates. On day 5, transduced T cells were transferred into tissue culture 24-well plates and expanded with IL7 and IL15 (IL7: 10 ng/mL; IL15: 5 ng/mL) for another 2 to 7 days. Non-transduced (NT) T cells were prepared in the same way, except for no retrovirus was added. For the generation of GFP.ffluc-expressing EDB-CAR T cells, activated T cells were transduced with two retroviral vectors, one encoding the EDB-CAR and the other GFP.ffluc. All experiments were performed 7–14 days post-transduction using unsorted ‘bulk’ CAR T cells. Biological replicates were performed using PBMCs from different healthy donors.

Flow cytometry

A FACSCanto II (BD) instrument was used to acquire flow cytometry data, which was analyzed using FlowJo v10 (FlowJo). For surface staining of tumor cells, HUVECs, and newly generated CAR T cells, samples were washed with and stained in PBS (Lonza) with 1% FBS (HyClone). For all experiments, matched isotypes or known negatives (e.g. NT T cells) served as gating controls along with positive control (e.g. anti-CD4 in all colors). LIVE/DEAD® Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain Kit (Invitrogen) was used as a viability dye. T cells were evaluated for CAR expression post-transduction with an anti-human IgG, F(ab’)2 fragment specific-AF647 (Jackson ImmunoResearch) or anti-CD19-PE (clone J3–119, Beckman Coulter). The following antibodies specific for human T-cell surface markers were used: anti-CD3-APC (clone UTCH1, Beckman Coulter), anti-CD4-Pacific Blue (clone SK3, BioLegend), anti-CD8-PerCPCy5.5 (clone SK1, BioLegend), anti-CD19-BV421 (clone HIB19, BD), anti-CCR7-AF488 (clone G043H7, BioLegend), anti-CD45RA-APC-H7 (clone HI100, BD), F(ab’) Goat IgG (AF647: 005600003, Jackson Labs). For detecting EDB expression in tumor cells and fibroblasts, we synthesized an L19 mAb with a hIgG1 heavy chain and human kappa light chain, which recognizes human and murine EDB based on the L19 sequence of our CAR and a previous report in the literature (Supplementary Fig. S3; ThermoFisher Scientific) (21). The antibody was conjugated using the Lightning-Link® R-PE Antibody Labeling Kit (Novus Bio). For intracellular staining, cells were permeabilized using the Cytofix/Cytoperm™ Fixation/Permeabilization Solution Kit (BD). Anti-human EphA2-APC (clone 371805, R&D) was used to detect EphA2 expression in HUVEC cells.

Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

mRNA extraction from 1×106 to 1×107 LM7. A549, U87 tumor cells and fibroblasts was performed using the Maxwell RSC SimplyRNA Blood kit (Promega AS1380) on a Maxwell RSC instrument. RT-qPCR was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using a one-step kit utilizing 800 ng of template, 3 biological replicates, normalized to GAPDH for delta Ct (ThermoFisher). Previously published sequences were used for EDB PCR primers (11), and GAPDH PCR primers (GAPDH control reagents) were purchased from Life Technologies. Reactions were completed on the Applied Bioscience QuantStudio 6 Flex and analyzed using QuantStudio software (ThermoFisher).

HUVEC capillary assays

HUVEC capillary assays were performed using the In Vitro Angiogenesis Assay Kit (Millipore) per manufacturer’s instructions seeding 10,000 cells per well. 30,000 CAR- or NT T cells were added to these capillary structures as judged by microscopic examination. Capillary structures were imaged on a Nikon Ti 12 hours after the CAR or NT T cells.

Coculture assay

1×106 NT or CAR T cells from healthy donors were cocultured alone or with 5×105 LM7, U87, U87FN−/−, or A549 cells without the provision of exogenous cytokine. For recombinant protein studies, recombinant human fibronectin (rhFN)-EDB (Abcam) was added at increasing concentrations (0.5, 1, 10 ng/mL) for 3 hours at 37°C. Plates were washed, and 5×105 T cells were plated. After 24 hours, supernatant was collected and frozen at −20°C for later analysis.

Cytokines were measured using human IFNγ and IL2 ELISA kits (R&D Systems). Supernatant was diluted 1:10 when required (if absorbance was above the detection limit the ELISA was re-run with dilution). 100 μL of supernatant in technical triplicates were analyzed for each biological replicate on a Tecan Infinite M Plex plate reader utilizing Magellan software (Tecan). Concentration was calculated using a standard curve included in the ELISA kits as per manufacturer’s directions.

Fibronectin ELISA

1×106 cells/mL of U87, U87FN−/−, A549, A673, LM7 cells and fibroblasts were harvested after 72 hours of culture. Cells were lysed with cell lysis buffer (Sigma) and collected media was snap frozen. Human fibronectin was detected by ELISA (R&D, DFBN10); 50 μL of undiluted media or cell lysate were analyzed for each biological replicate on Tecan Infinite M Plex plate reader utilizing Magellan software (Tecan). Concentration was calculated using a standard curve included in the ELISA kits as per manufacturer’s directions.

Xenograft mouse models

Animal experiments followed a protocol approved by St. Jude Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All experiments utilized 6–8-week NOD-scid IL2Rgammanull (NSG) mice obtained from St. Jude NSG colony. Subcutaneous tumor models: Mice were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) with 2×106 tumor cells (U87, U87FN−/−, A549, or A673) in Matrigel (Corning; 1:1 diluted in PBS). For the in vivo study in which mice received an admixture of U87 and U87FN−/− cells, cells were mixed prior to s.c. injection to achieve the following percentages of U87 cells: 100%, 90%, 70%, 10%, 0%. On day 7, mice received a single intravenous (i.v.) dose of 1×106 fresh NT or CAR T cells from healthy donors via tail vein injection. Tumor growth was assessed by serial, weekly, caliper measurements. Mice were euthanized when i) they met physical euthanasia criteria (significant weight loss, signs of distress); ii) the tumor burden was approximately 3,000 mm3; or iii) recommended by St. Jude veterinary staff. For the re-challenge experiments, mice received a single intravenous (i.v.) dose of 1×106 fresh tumor cells from healthy donors via tail vein injection. For studies to determine the presence of CD31-positive endothelial cells, tumors were harvested post euthanasia and placed in formalin for paraffin embedding. For studies to determine the presence of FN or EBD, tumors were harvested post euthanasia, and half of the tumor was collected for fresh frozen processing and the other half placed in formalin for paraffin embedding.

Intravenous tumor model:

Mice were injected i.v. with 2×106 tumor cells (A549) via tail vein injection, and on day 7, received a single i.v. dose of 1×106 fresh NT or CAR T cells. Mice were euthanized when they reached i) the bioluminescence flux endpoint of 2×1010 on two consecutive measurements (as described below) and/or ii) the above-mentioned general euthanasia criteria.

Safety study:

Non-tumor bearing mice received a single i.v. dose of 1×107 NT or 1×106 or 1×107 CAR T cells expressing GFP.ffLuc. Infused T cells were tracked by bioluminescence imaging (as described below), and on day 14 post T-cell injection, kidneys, liver, lung, and spleen were harvested post euthanasia for analysis.

Experiments with CD31-positive vascular endothelial cells

Mice were injected s.c. with 2×106 U87 or A673 tumor cells in Matrigel (Corning; 1:1 diluted in PBS). At Day 14, single-cell suspensions were prepared from harvested xenograft tumors, minced (~0.5mm pieces) and digested in collagenase II (Worthington, 50 μl enzyme per 0.1 g tissue) for 30 minutes at 37°C, filtered through a 70 μM cell strainer, and enriched for CD31-positive cells using MicroBeads (Miltenyi). MACS enrichment was performed using a Miltenyi autoMACS ProSeparator (Possel DS program with following reagents: anti-CD31 REAfinity™ PE (Miltenyi), anti-PE MicroBeads (Miltenyi)). CD31-enriched cells were stained for DAPI (Invitrogen), gated as single, viable cells, and the top 25% CD31-PE+ were sorted using the BDFACS Aria III. Post sorting, 15,000 cells were plated into 0.1 mg/mL anti-murine CD31 (BD)-coated wells, and after 24 hours, 30,000 CAR- or NT T cells were added per well. After 24 hours, T-cell activation was assessed by determining the concentration of IFNy in culture media using an ELISA (Human IFNy, see method section ‘ELISA’ for detail), and the cytolytic activity was determined using a standard MTS assay (see method section ‘MTS assay’ for detail).

MTS assay

A CellTiter96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega) was utilized to assess CAR T-cell cytotoxicity. In a 96-well plate, 12,500 U87, A549, and U87FN−/−, 10,000 HUVECs or CD31-positive sorted cells, or 15,000 LM7 cells or primary fibroblasts were cocultured with serial dilutions of CAR T cells and NT T cells at the indicated effector to target ratios in the figure panels. Media and tumor cells alone served as controls. Each condition was plated in triplicate. After 5 days for tumor cells, 3 days for HUVECs, and 24 hours for CD31+ sorted cells, the media and T cells were removed by gently pipetting up and down to avoid disrupting adherent tumor cells, and live cells were determined according to the manufacturer’s instructions utilizing a Tecan Infinite M Plex plate reader utilizing Magellan software (Tecan). Percent live tumor cells were determined by the following formula: (sample-media alone)/(tumor alone-media alone)*100.

Bioluminescence imaging

Mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 150 mg/kg of D-luciferin (ThermoFisher) 5–10 minutes before imaging, anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane purchased through St. Jude’s Center for In Vivo Imaging and Therapeutics, and imaged with a Xenogen IVIS-200 imaging system. Emitted photons were quantified using Living Image software (Caliper Life Sciences). Mice were imaged once per week to track tumor burden, or 1–5 times per week to track T cells.

Angiosense imaging

Mice where anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane and received a single i.v. dose of Angiosense 750 (2 nmol/100 μL; PerkinElmer; NEV10011EX) as recommended by the manufacturer. Administered Angiosense 750 was allowed to equilibrate in mice for 24 hours before imaging using a Xenogen IVIS-200 imaging system. Fluorescence signals were quantified using Living Image software (Caliper Life). Relative fluorescent units (RFU) where calculated by measuring tumor fluorescence subtracted from the background of mouse auto-fluorescence divided by tumor volume.

Immunohistochemistry

For CD31 immunohistochemistry (IHC), tumor samples were fixed and embedded in paraffin, and 8 μm sections were cut and mounted on slides. The sections were then processed and stained with anti-CD31 (Dianova, clone SZ31, cat. DIA 310). CD31 was only scored on tumors +/− 700 mm3 from the average tumor size in order to best control for the impact tumor size variation has on vascularization. CD31 expression was calculated by independent blind-scoring, and images were acquired using an Axio Scan Z.1. The tissue (kidneys, liver, lung, spleen) of the safety study (see ‘Xenograft mouse model’ section) were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Stained HE sections were reviewed by light microscopy and interpreted by a board-certified veterinary pathologist (CAR T cells were considered safe if no tissue damage was observed).

To detect fibronectin expression, a Leica BOND-MAX automated stainer (Leica Biosytems, Buffalo Grove, IL) was used with the following protocol and reagents: anti-fibronectin clone EP5 (Santa Cruz, SC-8422), Leica BOND-MAX automated stainer (Leica Biosytems, Buffalo Grove, IL) was used with the following manufacturer-supplied protocol, IHC F. All reagents were provided by Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, including the Leica Bond Dewax solution (AR9222), Leica Bond wash solution (AR9590), 3–4% (v/v) hydrogen peroxide for a 5-minute peroxide block (included in Bond Polymer Refine Detection kit DS9800), and HIER solution using the Bond Epitope Retrieval Solution 2 (ER2, AR9640) which was performed for 30 minutes. The primary antibody was incubated for 30 minutes. The Bond Polymer Refine Detection Kit reagents were used for visualization (DS9800).

To detect EBD expression, tumors were fixed in ice-cold acetone for 20 minutes and immunostained using the L19 mAb on a Ventana DISCOVERY ULTRA automated stainer (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc., Tucson, AZ). HIER was carried out for 32 minutes at 37oC using cell conditioning media 2 (Roche, CC2, cat no. 950–223), followed by visualization with a rabbit anti-human IgG Fc Secondary antibody HRP (ThermoFischer Scientific, #31423), OmniMap anti-rabbit HRP (760–4311), and the DISCOVERY ChromoMap DAB kit (760–159). Unaffected, morphologically normal murine epithelium served as an internal negative tissue control to compare with positive immunoreactivity that was visualized in human tumor cells, the collagenous interstitium, and murine folliculosebaceous units.

Both the fibronectin and EDB IHCs were evaluated using visual estimations of immunoreactivity to determine the presence or absence of the protein marker as well as comparison of immunoreactivity in experimental samples with what was observed in the positive tissue controls.

TCGA analysis

Exon quantification in reads-per-kilobase-million (RPKM) were manually downloaded from the legacy GDC data portal (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/legacy-archive/search/f). The exons in these mRNAseq samples were quantified by the TCGA RNAseqV2 pipeline (https://webshare.bioinf.unc.edu/public/mRNAseq_TCGA/UNC_mRNAseq_summary.pdf). Representative TCGA samples of solid and brain tumors were selected for analysis, including adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC; n=79), bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA; n=166), breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA; n=118), cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma (CESC; n=200), cholangiocarcinoma (CHOL; n=57), esophageal carcinoma, glioblastoma multiforme (GBM; n=174), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC; n=135), kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC; n=103), kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (KIRP; n=200), lower grade glioma (LGG; n=200), liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC; n=188), lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD; n=153), lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC; n=134), mesothelioma (MESO; n=80), ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma (OV; n=82), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD; n=183), pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma (PCPG; n=187), prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD; n=200), rectum adenocarcinoma (READ; n=177), sarcoma (SARC; n=265), skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM; n=200), stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD; n=154), testicular germ cell tumors (TGCT; n=156), thyroid carcinoma (THCA; n=200), thymoma (THYM; n=244), uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (UCEC; n=200), uterine carcinosarcoma (UCS; n=57), and uveal melanoma (UVM; n=80). Two hematologic malignancies were also incorporated, including lymphoid neoplasm diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBC; n=48), and acute myeloid leukemia (AML; n=95). A java program was used to extract the EDB exon expression from the RPKM files. The EDB exon expression boxplot was generated using an R package ggplot2 under R version 3.5.1. Code from our analysis is available in the github repository (https://github.com/gatechatl/EDB_Exon_Expression).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed at least in triplicates. For comparison between two groups, a two-tailed t-test was used. For comparisons of three or more groups, values were log-transformed as needed and analyzed by ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test. Survival was analyzed by Kaplan-Meier method and by the log-rank test. Bioluminescence imaging data were analyzed using either ANOVA, t-test, or area under the curve (AUC). Statistical and AUC analyses were conducted with Prism software (Version 9.0.0, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

EDB-CAR T cells recognize and kill EDB-positive tumor cells

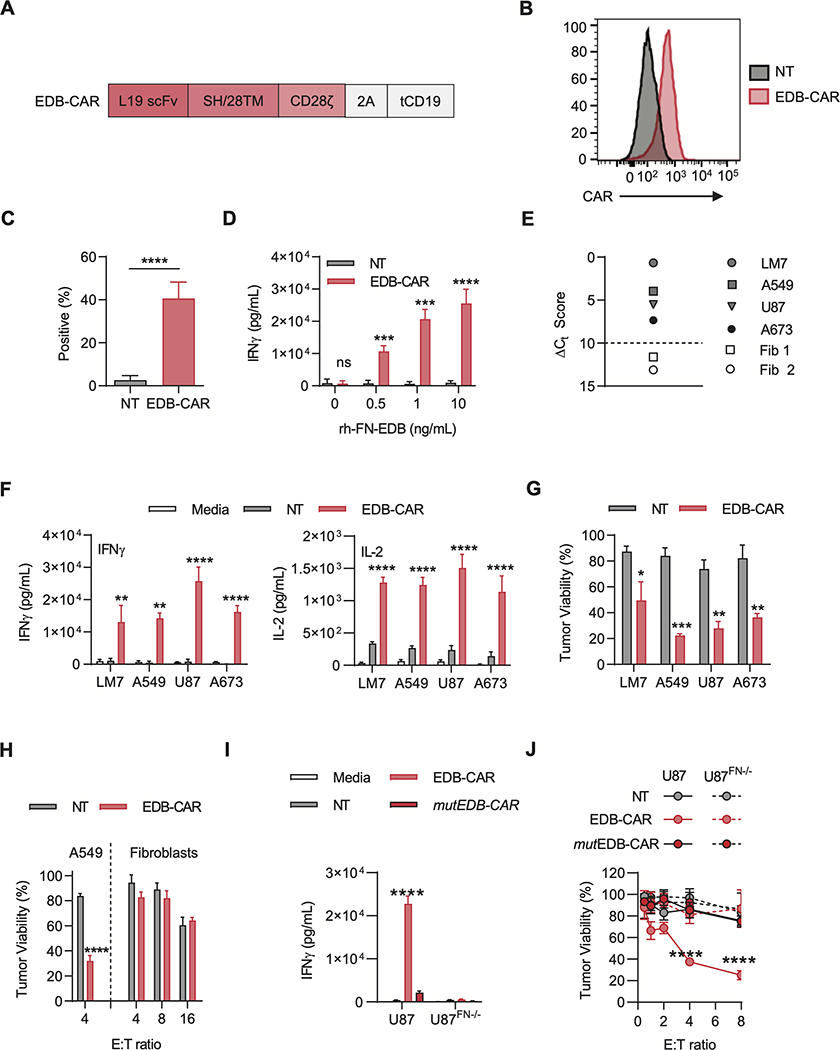

We generated a retroviral construct encoding an EDB-specific CAR consisting of an EDB-specific scFv derived from the L19 mAb (13), a short hinge/CD28 transmembrane domain, and a CD28ζ signaling domain. The vector also encoded a 2A sequence and truncated CD19 (tCD19; Fig. 1A). EDB-CAR T cells were generated by standard retroviral transduction, and 7 to 10 days post-transduction, CAR expression was determined by flow cytometric analysis using anti-F(ab’)2. A mean of 35.6% of T cells were CAR-positive (Fig. 1B-C). Retroviral T-cell transduction was confirmed using anti-CD19 (Supplementary Fig. S4A-B). EDB-CAR T cells contained a mixture of CD4- and CD8-positive T cells, and further T-cell subset analysis revealed the presence of naïve, central memory, effector memory, and terminally differentiated memory T cells (Supplementary Fig. S4C-D).

Figure 1: Generation and functional characterization of EDB-CAR T cells.

(A) Scheme of retroviral vectors encoding the EDB-CAR, a 2A sequence, and truncated CD19 (tCD19); SH: short hinge; TM: transmembrane domain. (B-C) EDB-CAR expression was determined on T cells 7 days post-transduction by flow cytometric analysis. (B) Representative histogram (Black-filled line: NT T cells; Red-filled line: EDB-CAR transduced T cells) and (C) summary plot (n=7; Student’s t-test; ****p<0.0001). (D) NT and EDB-CAR T cells were incubated for 24 hours with increasing concentrations of rhFN-EDB-coated wells. IFNγ production in supernatants was determined by ELISA (n=4; two-way ANOVA; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001). (E) EDB expression of LM7, A673, A549, and U87 tumor cells, and two primary fibroblast cell lines (Fib 1, Fib 2) determined by RT-qPCR; dotted line represents the ΔCt score above which samples are considered positive. (F) NT and EDB-CAR T cells were incubated for 48 hours with EDB-positive tumor cells. IFNγ and IL2 production in supernatants was determined by ELISA (two-way ANOVA; ****p<0.0001). (G) Cytolytic activity of NT or EDB-CAR T cells at a E:T ratio of 4:1 against EDB-positive tumor cells (MTS assay; n=3; two-way ANOVA; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001). (H) Cytolytic activity of NT or EDB-CAR T cells against primary fibroblasts (data of Fib 1 and Fib 2 was combined) at the indicated E:T ratios, with A549 serving as controls (n=3; two-way ANOVA; ****p<0.0001). (I) NT, EDB-CAR, or mutEDB-CAR T cells were incubated for 48 hours with U87 or U87FN−/− cells. IFNγ production in supernatants was determined by ELISA (n=3; two-way ANOVA; ****p<0.0001). (J) Cytolytic activity of NT, EDB-CAR, or mutEDB-CAR T cells against U87 or U87FN−/− cells (n=3; two-way ANOVA; ****p<0.0001). Mean+SEM is shown in panels.

To initially demonstrate that EDB-CAR T cells recognized EDB, non-transduced (NT) or EDB-CAR T cells were cultured on plates coated with increasing amounts of recombinant human FN-EDB (rhEDB) protein. After 24 hours of culture, only EDB-CAR T cells produced significant amounts of IFNγ (Fig. 1D), demonstrating activation of EDB-CAR by its target antigen. We confirmed EDB expression in a broad range of solid tumors and brain tumors from the cancer genome atlas (TCGA)(Supplementary Fig. S5) and focused our functional studies on sarcoma (osteosarcoma, LM7; Ewing’s sarcoma, A673), lung adenocarcinoma (A549), and high-grade glioma (U87). All four cell lines expressed EDB as judged by RT-qPCR using primary human fibroblasts from two healthy donors as negative controls (Fig. 1E). To confirm EDB expression, we performed cell surface and intracellular staining for EDB using the L19 mAb. 85.6–99.5% of U87 and A549 cells were EBD-positive by cell surface or intracellular staining; 73.5% of A673 cells were EBD-positive by intracellular staining, with <10% cell surface staining; and ~14% of LM7 cells were EBD-positive by cell surface and intracellular staining (Supplementary Fig. S6A). Normal fibroblast and fibronectin-knockout U87 cells (U87FN-/) served as negative controls. ELISAs for fibronectin demonstrated a significant concentration of fibronectin in LM7 cells and normal fibroblasts compared to U87FN−/− controls in media and cell lysates of U87, A549, and A673 cells (Supplementary Fig. S6B-C). EDB-CAR T cells produced significant amounts of IFNγ and IL2 in 48-hour coculture assays with all four cell lines compared to NT T cells (Fig. 1F). EDB-CAR T cells also had significant cytolytic activity, in contrast to NT T cells, in a standard MTS-based cytotoxicity assay (Fig. 1G). In contrast, EDB-CAR T cells had no cytolytic activity against primary human fibroblasts even at high effector to target (E:T) ratios of 16:1 (Fig. 1H). EDB-CAR T cells did not recognize primary human fibroblasts, determined by IFNγ production in coculture assays (Supplementary Fig. S7).

To provide further evidence that target cell recognition depended on the expression of a functional EDB-CAR in T cells and EDB in target cells, we conducted experiments with the U87FN−/− cells as targets, and generated a nonfunctional EDB-CAR by mutating the three ITAMs in the zeta signaling domain of the CAR (mutEDB-CAR). mutEDB-CAR T cells did not recognize or kill U87 cells, in contrast to EDB-CAR in T cells (Fig. 1I), and U87FN−/− cells were not recognized or killed by EDB-CAR T cells (Fig. 1J). Thus EDB-CAR T cells recognizeed and killed EDB-positive tumor cells in an EDB-specific manner.

Because EDB is secreted, we wanted to address if there was bystander killing of targets that do not express EDB (Supplementary Fig. S8A). First, we demonstrated that conditioned media of U87 cells contained EDB, which could activate EDB-CAR T cells, as judged by IFNγ production, in contrast to conditioned media from U87FN−/− cells (Supplementary Fig. S8B). Next, we cocultured EDB-positive (U87) or EDB-negative (U87FN−/−, fibroblasts) target cells with NT or EDB-CAR T cells in the presence of conditioned media from EDB-positive or EBD-negative cells and performed an MTS assay. EDB-positive U87 cells were killed by EDB-CAR T cells regardless of the added conditioned media. In contrast, significant killing of EBD-negative target cells was only observed in the presence of conditioned media from EDB-positive cells (Supplementary Fig. S8C).

EDB-CAR T cells have potent antitumor activity in preclinical solid tumor models

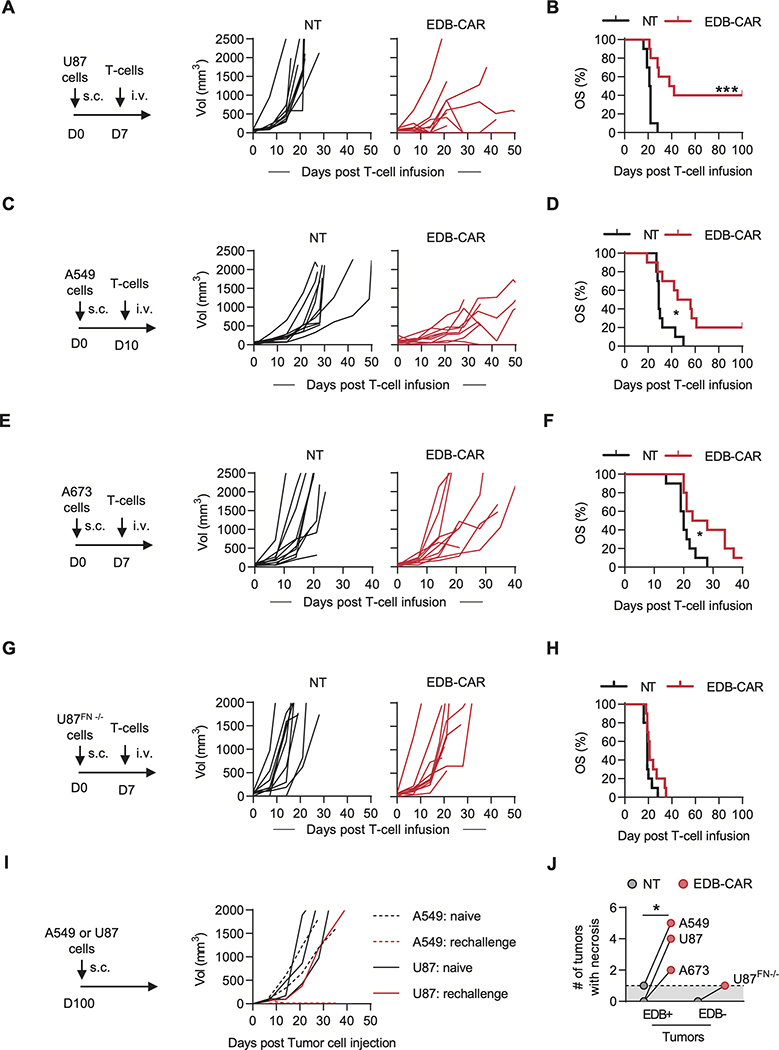

Having established that EDB-CAR T cells had significant EDB-specific antitumor activity in vitro, we next set out to evaluate their antitumor activity in vivo. We utilized three subcutaneous (s.c.; U87, A673, A549) and one intravenous (i.v.) lung (A549.GFP.ffluc) NSG tumor models and confirmed fibronectin (Supplementary Fig. S9) and EDB (Supplementary Fig. S10) expression in the s.c. tumors by immunohistochemistry. On day 7 or 10 post tumor cell injection, mice received a single i.v. dose of 1×106 NT or EDB-CAR T cells. In all models, EDB-CAR T cells had antitumor activity in comparison to mice injected with NT T cells, resulting in a significant survival advantage (Fig. 2A-F; Supplementary Fig. S11). To confirm that the observed antitumor activity depended on EDB expression by tumor cells, we used U87FN−/− cells in the s.c. model. Although U87FN−/− tumors readily grew in NSG mice, EDB-CAR T cells had no antitumor activity (Fig. 2G-H). To further confirm specificity and to get insight into the in vivo expansion of EDB-CAR T cells, we performed an in vivo experiment with mutEDB- and EDB-CAR T cells, which were also genetically modified to express GFP.ffluc, in the s.c. A549 model (Supplementary Fig. S12A). Only EDB-CAR T cells had significant antitumor activity (Supplementary Fig. S12B-C) and expanded and/or persisted longer than mutEDB-CAR T cells, determined by AUC analysis within the first 10 days post CAR T-cell infusion (Supplementary Fig. S12D). To assess long-term, functional persistence of EDB-CAR T cells, 5 mice that achieved a complete response (CR)(2 mice: s.c. A549 model; 3 mice: s.c. U87 model) were challenged with a second dose of their respective tumor cells on day 100. Five naive mice served as controls. Tumors grew in 5/5 control mice, in contrast to only 1/5 mice that had previously been treated with EDB-CAR T cells (Fig. 2I).

Figure 2: EDB-CAR T cells have antitumor activity in vivo.

(A-H) 2×106 of the indicated tumor cells were injected into NSG mice s.c.. On day (D)7 (U87, A673, U87FN−/−) or D10 (A549) post tumor cell injection, mice received a single i.v. dose of 1×106 NT or EDB-CAR T cells. Tumor growth was monitored weekly by caliper measurement (n=10 mice/group; 5 mice/T-cell donor; log-rank test; *p<0.05; ***p<0.001). (A) Experimental scheme and tumor growth for the U87 model. (B) U87 model: Kaplan-Meier survival curve. (C) Experimental scheme and tumor growth for the A549 model. (D) A549 model: Kaplan-Meier survival curve. (E) Experimental scheme and tumor growth for the A673 model. (F) A673 model: Kaplan-Meier survival curve. (G) Experimental scheme and tumor growth for the U87FN−/− model. (H) U87FN−/− model: Kaplan-Meier survival curve. (I) NSG mice that survived long-term post initial A549 (n=2) or U87 (n=3) s.c. tumor cell injection and EDB-CAR T-cell therapy were re-challenged with a single s.c. dose of cognate tumor cells. Naïve mice served as controls. Tumor growth was monitored weekly by caliper measurement. (J) Macroscopic tumor necrosis of tumors <2,000 mm3 (Student’s t-test; *p<0.05) of the experiments shown in panels A-I; dots represent how many tumors had macroscopic necrosis out of 10 tumors per cell type; dotted line represent baseline (1 tumor with macroscopic necrosis).

Because we demonstrated ‘bystander killing’ in our in vitro studies, we next assessed this in vivo by injecting admixtures of U87 and U87FN−/− cells injected s.c. into mice (100%, 90%, 70%, 10%, 0% U87 cells). On day 7, mice received a single dose of EDB-CAR T cells. Although the antitumor activity decreased with decreasing percentage of U87 cells, EDB-CAR T cells still had significant antitumor activity against 10% U87 tumors (Supplementary Fig. S13A-C).

EDB-CAR T cells target the vasculature and tumor-associated endothelial cells

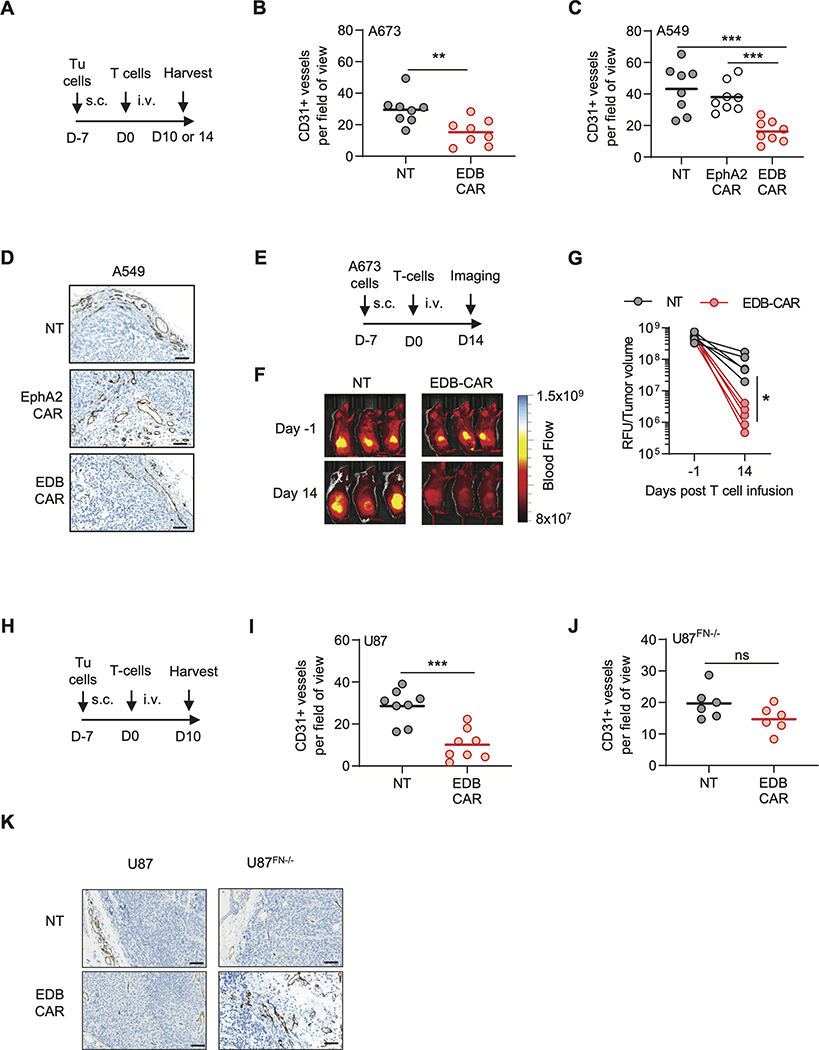

There was a significant higher incidence of macroscopic necrosis of s.c. EDB-positive tumors <2,000 mm3, determined by visual inspection in mice that received EDB-CAR T cells (Fig. 2J). We therefore wanted to evaluate if EDB-CAR T cells targeted the tumor vasculature using two independent approaches. First, we injected i.v. NT or EDB-CAR T cells into s.c. A549 or A673 tumor-bearing mice. On day 10 or 14 post T-cell injection, tumors were processed for CD31 via IHC to enumerate endothelial cells. As an additional control, EphA2-CAR T cells were included in the s.c. A549 model. There was a significant reduction of intratumoral CD31-positive endothelial cells with EDB-CAR T-cell treatment in comparison to NT and EphA2-CAR T-cell treatment groups (Fig. 3A-D, Supplementary Fig. S14). The second approach relied on direct imaging of the tumor vasculature using AngioSense on day 14 post NT or EDB-CAR T-cell injection in the s.c. A673 model. Our results demonstrated that A673 tumors treated with EDB-CAR T cells contained a lower number of blood vessels (Fig 3E-G).

Figure 3: EDB-CAR T cells target intratumoral CD31-positive endothelial cells.

(A-D) A673 or A549 s.c. tumor-bearing mice received a single dose of NT, EDB-CAR, or EphA2-CAR (A549 only) T cells. Tumors were processed on day (D)10 (A673) or 14 (A549) post T-cell injection and analyzed for CD31 expression (n=4 mice per group with each mouse bearing one tumor; dots represent average of three blind scores per tumor; bars represent average per cohort, two fields-of-view (FOV) per tumor). (B) CD31+ vessels/FOV in the A673 model; Student’s t-test; **p<0.01. (C) CD31+ vessels/FOV in the A549 model; one-way ANOVA; *p<0.05). (D) Representative IHC images for CD31 staining of A549 tumors. Images at 40x magnification; scale bar: 100μm. (E-G) A673 s.c. tumor-bearing NSG mice were imaged using Angiosense 750 on day −1 and day 14 post NT or EDB-CAR T-cell injection. (E) Experimental scheme. (F) Representative images. (G) Quantitation (relative light units (RLU) divided by tumor volume is plotted; n=5 mice/treatment group; Student’s t-test; *p<0.05). (H) Experimental scheme. s.c. tumor-bearing (I) U87 or (J) U87FN−/− NSG mice received a single i.v. dose of NT or EDB-CAR T cells. Tumor were processed on day 10 post T-cell injection and analyzed for CD31 expression (n=4 mouse/tumors per group except for U87FN−/−/NT T-cell group (n=3) with dots representing three blind score per FOV; bars represent average per cohort, 2 FOV per tumor). (K) Representative IHC images for CD31 for U87 and U87FN−/− cells. Images at 40x magnification; scale bar: 100μm.

To confirm that EDB-CAR T cells targeted vascular endothelial cells, we performed experiments with HUVEC cells and freshly isolated CD31-positive endothelial cells from U87 and A673 tumors. HUVEC cells expressed EDB by flow cytometric analysis (Supplementary Fig. S15A) and were recognized and killed by EDB-CAR T cells (Supplementary Fig. S15B-C). NT T cells served as negative, and EphA2-CAR T cells as positive controls. EDB-CAR T cells also killed capillaries formed by HUVEC cells in contrast to NT T cells (Supplementary Fig. S15D). EphA2-CAR T cells did not kill preformed capillaries because the CAR recognizes an epitope that is not accessible in cell structures that from tight junctions (22). EDB-CAR T cells also recognized and killed CD31-positive endothelial cells (Supplementary Fig. S16A-C).

To establish if endothelial cells produced sufficient EDB to become targets or if their killing relied on binding of tumor cell-secreted EDB on their cell surface, we took advantage of our U87 and U87FN−/− models. U87 and U87FN−/− s.c. tumor-bearing mice received on day 7 one i.v. dose of NT or EDB-CAR T cells. On day 10 post T-cell injection, mice were euthanized and tumors processed for CD31 IHC. In U87 tumors, EDB-CAR T cells induced a significant reduction of intratumoral CD31-positive endothelial cells in comparison to NT T cells (Fig 3H,I,K; Supplementary Fig. S17A). However, we observed no significant difference between the NT and EDB-CAR T-cell treatment groups in U87FN−/− xenografts (Fig 3J-K, Supplementary Fig. S17B), indicating that EDB secretion by neighboring tumor cells was essential for the observed anti-vascular activity of EDB-CAR T cells.

Safety of EDB-CAR T cells

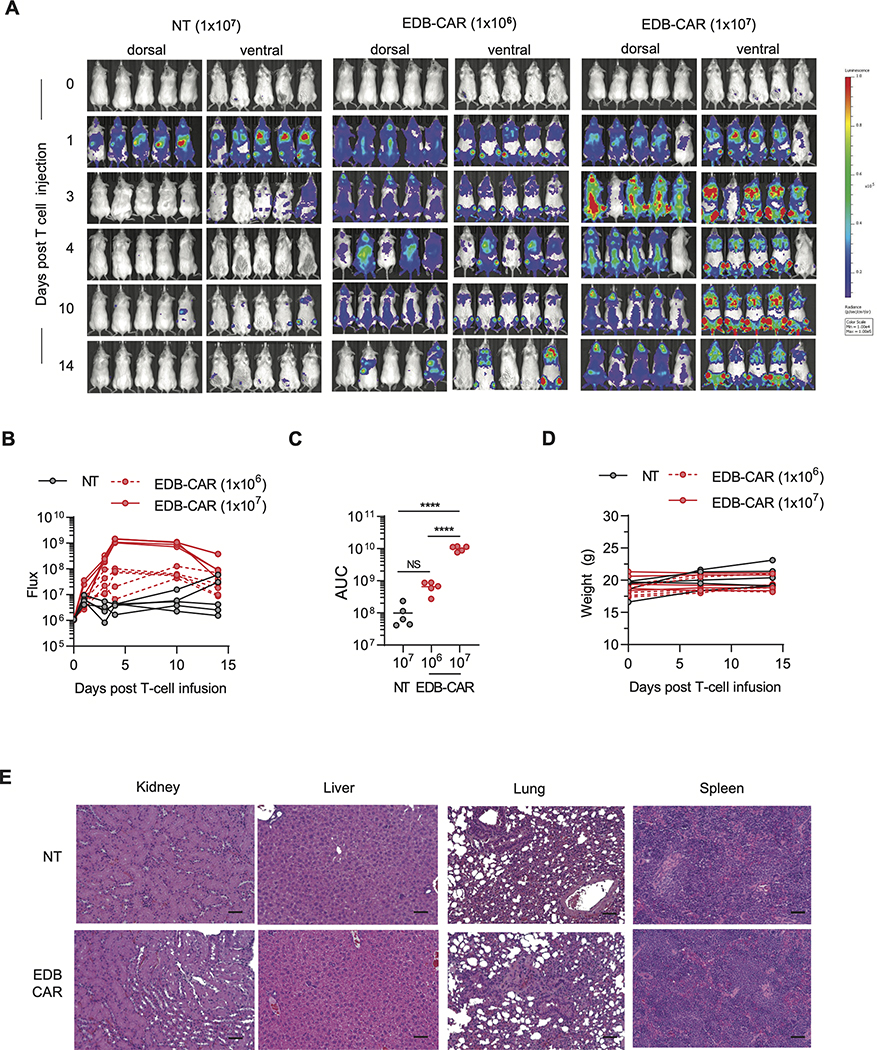

Because murine and human EDB are 100% identical (9), we also used our NSG tumor model to assess safety. Injection of 1×106 EDB-CAR T cells did not result in weight loss, and long-term follow-up showed continued weight gain of treated mice (Supplementary Fig. S18). We performed additional experiments with GFP.ffLuc-expressing EDB-CAR T cells to assess their expansion in non-tumor bearing mice. Non-tumor bearing mice received one i.v. dose of 1×107 NT or 1×106 or 1×107 EDB-CAR T cells. Only after the injection of 1×107 EDB-CAR T cells did we observed significant, transient expansion (Fig. 4A-D) in comparison to NT T cells. Mice that received 1×107 NT or EDB-CAR T cells were euthanized on day 14, and major organs (kidney, liver, lung, spleen) were subjected to pathological analysis. No histological differences were observed between examined tissues of both groups of mice (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4: EDB-CAR T cells transiently expand in non-tumor bearing mice post infusion.

Mice were injected with one i.v. dose of GFP.ffLuc-expressing EDB-CAR (1×106 or 1×107) or NT (1×107) T cells (n=5 mice/group). (A) Bioluminescence images. (B) Summary of bioluminescence data. (C) Area under the curve (AUC) analysis; two-way ANOVA; ****p<0.001; n.s., not significant). (D) Mouse weight measured in grams (g). (E) Mice were euthanized on day 14, and kidneys, liver, lungs, and spleens were subjected for pathological analysis (5 mice/group). Representative stained hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) sections from each group are shown at 20x magnification; scale bar: 50 μm.

DISCUSSION

Collectively, our studies demonstrated that T cells, expressing an EDB-CAR with an antigen recognition domain derived from the L19 mAb, recognized and killed EDB-secreting tumor cells. EDB-CAR T cells had potent antitumor activity in three xenograft models representing lung cancer, sarcoma, and high-grade glioma. EDB-secreting tumor cells also redirected EDB-CAR T cells to CD31-positive endothelial cells of the tumor vasculature.

Fibronectin is encoded by 47 exons and has 27 splice variants according to GTEx. EDB is encoded by exon 25 and 4/27 splice variants contain this exon. EDB is expressed in a broad range of malignancies, which we confirmed using 4,684 TCGA samples. Among 31 types of cancers, expression was high in common cancers, such as breast and lung cancers, and in cancers with poor prognosis, including pancreatic adenocarcinoma and high-grade glioma. Although cancer-specific secretion of EDB has been exploited by numerous investigators for imaging purposes, targeted radiotherapy, or targeted delivery of anti-cancer drugs including cytokines (16,23), very few studies have been conducted that induce EDB-specific immune responses. One study finds that a prophylactic EDB vaccine reduces tumor growth and increases tumor necrosis without impairing wound healing in a preclinical fibrosarcoma model (24). Another study demonstrates that EDB-CAR T cells target tumor cells and the tumor vasculature in immune-competent animal models. However, no antitumor activity was observed in immunodeficient mice (25).

Here, we demonstrated in three tumor models using immunodeficient mice that tumor cells can be directly targeted with EDB-CAR T cells. For our studies, we used tumor cells for which we confirmed EDB and fibronectin expression by qPCR and flow cytometry (EDB) or ELISA (fibronectin) using U87FN−/− and fibroblasts as controls. Three of four cell lines secreted significant amounts of fibronectin in comparison to U87FN-/−. Fibroblast secreted only low amounts of fibronectin, which could be explained by either our culture conditions (26) or by the presence of other ECM molecules (like collagen) secreted by fibroblasts that bind fibronectin and interfere with the performed ELISAs. Although by qPCR all four cell lines expressed EDB, flow cytometric analysis revealed that only 2/4 cell lines expressed cell surface EDB and 3/4 cell lines had intracellular expression We believe that these discrepancies are due to technical issues because all four cell lines were recognized and killed by EDB-CAR T cells, and we confirmed the specificity of our CAR by using EDB-negative fibroblasts and U87FN−/− cells.

Being able to demonstrate antitumor activity by EDB-CAR T cells in vivo in xenograft models presents a significant advance because it highlights the feasibility of directly targeting cancer cells with CAR T cells that recognize secretory proteins that adhere to the cell surface. Our results also suggested bystander killing of EDB-negative tumor cells, presenting a distinct advantage in comparison to targeting membrane proteins. Other investigators have not observe antitumor activity of EDB-CAR T cells in xenograft models (7). These discrepant results are most likely explained by differences in CAR design: whereas the EDB binding domain of the published CAR consists of a heavy chain only antibody (VHHs or nanobody), we used a standard scFv encoding the EDB-specific L19 mAb. The EDB-specific nanobody and L19 scFv most likely bind to distinct epitopes within the EDB domain.

EDB-CAR T cells had significant anti-vascular activity, which we confirmed by two independent methods. In vivo studies with U87FN−/− cells revealed that EDB secretion by tumor cells was critical for the observed anti-vasculature activity. This is in contrast to several studies reporting that EDB is secreted by endothelial cells within the tumor vasculature (12). Because human and murine EDB are 100% identical, the murine origin of endothelial cells within xenograft tumors does not explain our finding (11). Possibly, lack of fibronectin secretion by the tumor cells could influence blood vessel formation. Indeed, the number of CD31-positive endothelial cells was lower in U87FN−/− than U87 tumors of mice that received NT T cells; however, this difference did not reach statistical significance. Clearly, additional studies in other models and are needed to further investigate our findings.

Although EDB-CAR T cells had antitumor activity, only in the U87 model, 40% of animals were cured with a follow up of three months. Limited antitumor activity might be explained several factors. First, we used low numbers of CAR T cells (1×106 per mice) in all of our therapeutic models. We also observed limited expansion of EDB-CAR T cells post infusion. In the future, we will therefore focus on optimizing CAR T-cell dosing and CAR design, and explore additional genetic modification of EDB-CAR T cells to enhance their effector function as reported in other model systems (27,28). These include expression of cytokines and/or chimeric cytokine receptors, or deleting negative regulators (29–32). Combining EDB-CAR T cells with CAR T cells that target cell surface tumor-associated antigens is another possibility. Lastly, studies in immune competent tumor models are warranted, which have a tumor microenvironment (TME) that is closer to human tumors than the TME in NSG mice.

Several other CARs have been developed that target the tumor vasculature, including CARs targeting VEGFR1, VEGFR2, PSMA, and TEM8 (33–35). Although VEGFR2-CAR T cells had promising antitumor activity in preclinical models, clinical activity (clinicaltrials.gov website, NCT01218867) is limited, and systemic delivery of TEM8-CAR T cells in one preclinical model is toxic (35). Because human and murine EDB are 100% homologous, our xenograft studies allowed us to evaluate the safety of EDB-CAR T cells. First, we did not observe any clinical signs of toxicity, including weight loss, in mice treated with one i.v. dose of EDB-CAR T cells in any of our efficacy studies. Second, we performed studies in non-tumor bearing mice, in which mice received a single a ten-fold higher dose of GFP.ffLuc-expressing EDB-CAR T cells. Although there was transient, significant expansion at the 1×107 cell dose, we did not observe any overt toxicity, and histological examination of major organs 14 days post injection revealed no pathological findings, indicating our EDB-CAR T cells are well-tolerated with no overt on-target/off-tumor toxicity. At present, it is unclear if the observed transient expansion at the 1×107 CAR T-cell dose is due to the presence of low EDB in selected normal tissues or alloreactivity, and additional studies are needed and should also include careful examination of femur and hips because EDB-CAR T-cell expansion was observed at these sites by bioluminescence imaging.

Finally, our study highlights that a cancer-specific splice variant can be safely targeted with CAR T cells in vivo. Aberrant splicing is a ‘hallmark of cancer’ (8), and numerous splice variants have been described (36). Thus, we believe that our study provides the impetus to carefully mine existing gene expression databases for splice variants that could serve as CAR targets. In conclusion, EDB-CAR T cells had potent antitumor and anti-vascular activity in preclinical solid tumor models without overt toxicity. Thus, targeting EDB with CAR T cells has the potential to improve current CAR T-cell therapy approaches for solid tumors.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the research staff of St. Jude Centers and Cores (listed under ‘Funding’), who assisted in the conducting of the experiments.

Funding: The work was supported by the Alex Lemonade Stand Foundation and Cure4Cam Foundation (ALSF; Young Investigator Grant; JW), the Alliance for Cancer Gene Therapy (ACGT; SG), and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (GK, SG). Animal imaging was performed by the Center for In Vivo Imaging and Therapeutics, which is supported in part by NIH grants P01CA096832 and R50CA211481. Cellular images were acquired at SJCRH Cell & Tissue Imaging Center which is supported by SJCRH and NCI P30 CA021765. Gene editing of cell lines was performed by the Center for Advanced Genome Engineering (CAGE), which is supported in part by NCI P30 CA021765.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: JW, GK, and SG have patent applications in the fields of T-cell and/or gene therapy for cancer. SG has a research collaboration with TESSA Therapeutics, is a DSMB member of Immatics, and on the scientific advisory board of Tidal.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grupp SA et al. , Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for acute lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med 368, 1509–1518 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fry TJ et al. , CD22-targeted CAR T cells induce remission in B-ALL that is naive or resistant to CD19-targeted CAR immunotherapy. Nat Med 24, 20–28 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramos CA et al. , Clinical and immunological responses after CD30-specific chimeric antigen receptor-redirected lymphocytes. J Clin Invest 127, 3462–3471 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kakarla S et al. , Antitumor effects of chimeric receptor engineered human T cells directed to tumor stroma. Mol Ther 21, 1611–1620 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez M, Moon EK, CAR T Cells for Solid Tumors: New Strategies for Finding, Infiltrating, and Surviving in the Tumor Microenvironment. Front Immunol 10, 128 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brudno JN, Kochenderfer JN, Toxicities of chimeric antigen receptor T cells: recognition and management. Blood 127, 3321–3330 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sadelain M, Brentjens R, Rivière I, The basic principles of chimeric antigen receptor design. Cancer Discov 3, 388–398 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA, Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White ES, Muro AF, Fibronectin splice variants: understanding their multiple roles in health and disease using engineered mouse models. IUBMB Life 63, 538–546 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaspar M, Zardi L, Neri D, Fibronectin as target for tumor therapy. Int J Cancer 118, 1331–1339 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Midulla M et al. , Source of oncofetal ED-B-containing fibronectin: implications of production by both tumor and endothelial cells. Cancer Res 60, 164–169 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan ZA et al. , EDB fibronectin and angiogenesis -- a novel mechanistic pathway. Angiogenesis 8, 183–196 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pini A et al. , Design and use of a phage display library. Human antibodies with subnanomolar affinity against a marker of angiogenesis eluted from a two-dimensional gel. J Biol Chem 273, 21769–21776 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Emir E et al. , Characterisation and radioimmunotherapy of L19-SIP, an anti-angiogenic antibody against the extra domain B of fibronectin, in colorectal tumour models. Br J Cancer 96, 1862–1870 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moosmayer D et al. , Bispecific antibody pretargeting of tumor neovasculature for improved systemic radiotherapy of solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 12, 5587–5595 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sauer S et al. , Expression of the oncofetal ED-B-containing fibronectin isoform in hematologic tumors enables ED-B-targeted 131I-L19SIP radioimmunotherapy in Hodgkin lymphoma patients. Blood 113, 2265–2274 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santimaria M et al. , Immunoscintigraphic detection of the ED-B domain of fibronectin, a marker of angiogenesis, in patients with cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 9, 571–579 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gottschalk S et al. , Generating CTLs against the subdominant Epstein-Barr virus LMP1 antigen for the adoptive immunotherapy of EBV-associated malignancies. Blood 101, 1905–1912 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connelly JP, Pruett-Miller SM, CRIS.py: A Versatile and High-throughput Analysis Program for CRISPR-based Genome Editing. Sci Rep 9, 4194 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yi Z, Prinzing BL, Cao F, Gottschalk S, Krenciute G, Optimizing EphA2-CAR T Cells for the Adoptive Immunotherapy of Glioma. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 9, 70–80 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borsi L et al. , Selective targeting of tumoral vasculature: comparison of different formats of an antibody (L19) to the ED-B domain of fibronectin. Int J Cancer 102, 75–85 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coffman KT et al. , Differential EphA2 epitope display on normal versus malignant cells. Cancer Res 63, 7907–7912 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tijink BM et al. , (124)I-L19-SIP for immuno-PET imaging of tumour vasculature and guidance of (131)I-L19-SIP radioimmunotherapy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 36, 1235–1244 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huijbers EJ et al. , Vaccination against the extra domain-B of fibronectin as a novel tumor therapy. FASEB J 24, 4535–4544 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xie YJ et al. , Nanobody-based CAR T cells that target the tumor microenvironment inhibit the growth of solid tumors in immunocompetent mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116, 7624–7631 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adachi Y et al. , Fibronectin production by cultured human lung fibroblasts in three-dimensional collagen gel culture. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 34, 203–210 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mata M et al. , Inducible Activation of MyD88 and CD40 in CAR T Cells Results in Controllable and Potent Antitumor Activity in Preclinical Solid Tumor Models. Cancer Discov 7, 1306–1319 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hombach AA, Abken H, Costimulation by chimeric antigen receptors revisited the T cell antitumor response benefits from combined CD28-OX40 signalling. Int J Cancer 129, 2935–2944 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peng W et al. , Transduction of tumor-specific T cells with CXCR2 chemokine receptor improves migration to tumor and antitumor immune responses. Clin Cancer Res 16, 5458–5468 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feig C et al. , Targeting CXCL12 from FAP-expressing carcinoma-associated fibroblasts synergizes with anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 20212–20217 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shifrut E et al. , Genome-wide CRISPR Screens in Primary Human T Cells Reveal Key Regulators of Immune Function. Cell 175, 1958–1971.e1915 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wagner J, Wickman E, DeRenzo C, Gottschalk S, CAR T Cell Therapy for Solid Tumors: Bright Future or Dark Reality? Mol Ther, (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santoro SP et al. , T cells bearing a chimeric antigen receptor against prostate-specific membrane antigen mediate vascular disruption and result in tumor regression. Cancer Immunol Res 3, 68–84 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang W et al. , Specificity redirection by CAR with human VEGFR-1 affinity endows T lymphocytes with tumor-killing ability and anti-angiogenic potency. Gene Ther 20, 970–978 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petrovic K et al. , TEM8/ANTXR1-specific CAR T cells mediate toxicity in vivo. PLoS One 14, e0224015 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venables JP, Aberrant and alternative splicing in cancer. Cancer Res 64, 7647–7654 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.