Abstract

Background

People from minority ethnic groups are under-represented in dementia diagnosis, treatment, and care. The aim of this study was to examine barriers to accessing post-diagnostic care and support in minority ethnic communities from the perspective of primary care dementia coordinators in Denmark.

Method

A survey questionnaire investigating issues related to provision of care and support services in minority ethnic communities was conducted among 41 primary care dementia coordinators representing all Danish geographic regions. Responses were primarily based on five-point Likert scales. Results from geographic regions with different rates of people from minority ethnic communities with dementia were compared.

Results

Among the surveyed dementia coordinators, 95% generally thought that providing dementia care and support services to minority ethnic service users was challenging. Strategies for overcoming cultural and linguistic barriers were generally sparse. Uptake of most post-diagnostic services was perceived to be influenced by service users’ minority ethnic background. Communication difficulties, poor knowledge about dementia among minority ethnic service users, inadequate cultural sensitivity of care workers, and a lack of suitable dementia services for minority ethnic communities were highlighted as some of the main barriers. Not surprisingly, 97% generally found minority ethnic families to be more involved in provision of personal care and support compared to ethnic Danish families.

Conclusion

There is a need to develop methods and models for post-diagnostic care and support that include cultural awareness and diversity for interacting with different cultural communities.

Keywords: dementia, minority, ethnicity, access, healthcare, inequality

Introduction

As in other European countries, in Denmark most people with minority ethnic (ME) backgrounds are immigrants or first-degree descendants of immigrants from a non-western country (Nielsen et al., 2015). Although ME populations are generally younger than the majority population, the immigrants who came to Western Europe between the 1950s and 1970s are now ageing. Due to differences in demographic aging, a seven-fold increase in the number of people with dementia from ME backgrounds is predicted by 2050 in several countries, including the UK and Denmark, compared to a two-fold increase in the general population (All-Party Parlamentary Group (APPG) on Dementia, 2013; Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2015; Nielsen et al., 2015). As people from ME groups often have different needs and expectations of health- and social care services in dementia compared to majority populations in Nordic countries, it has been proposed that there is a general need to develop appropriate methods and models of care for people from ME communities (Nielsen et al., 2015).

Despite the need for dementia care in ME communities, previous studies have found the diagnostic rate in older ME populations to be lower than the majority population (Diaz, Kumar, & Engedal, 2015; Nielsen, Vogel, Phung, Gade, & Waldemar, 2011). The barriers to accessing dementia services have not been well studied in Nordic countries but may include language barriers, different help-seeking patterns, poor knowledge, and misconceptions about dementia, in addition to different cultural views on caregiving (Nielsen et al., 2015). In Denmark, people from ME groups with a diagnosis of dementia are 30% less likely to be prescribed anti-dementia medication and are 48% less likely to enter a nursing home (Stevnsborg, Jensen-Dahm, Nielsen, Gasse, & Waldemar, 2016), and compared to ethnic Danes, ME older people in Copenhagen were 42% less likely to utilize homecare or nursing home services (Hansen & Siganos, 2013). These differences in diagnostic, treatment, and care patterns are worrying as they may result in poorer dementia outcomes and care for people from ME groups.

In order to develop dementia services that are inclusive of ME groups, it is important to examine barriers to utilizing available public services. Ethnic inequalities in dementia treatment and care and the possible reasons for these inequalities have previously been explored in three comprehensive systematic reviews (Cooper, Tandy, Balamurali, & Livingston, 2010; Kenning, Daker-White, Blakemore, Panagioti, & Waheed, 2017; Mukadam, Cooper, & Livingston, 2011b). However, currently there is a scarcity of published research on dementia care and ME groups from outside traditionally multicultural societies, such as the USA, UK, and Australia, and none of these have specifically focused on barriers to post-diagnostic care and support.

The aim of this study was to examine barriers to accessing post-diagnostic care and support in ME communities from the perspective of primary care dementia coordinators in Denmark.

Study setting and methods

In Denmark, free access to medical care is available for all legal residents, and access to most social care is either free or obtained at reduced rates with the main part of the costs subsidized by the state. There are only a few small private hospitals and care services, and none of these offer specific services for ME groups. Although there are no official estimates, the number of illegal immigrants in Denmark is generally considered to be very small. Dementia diagnostic services are generally located in hospital-based memory clinics, while post-diagnostic medical treatment and follow-up is the responsibility of general practitioners. Post-diagnostic social care and support is organized by primary care dementia coordinators employed in all Danish geographic and legislative municipalities, who have the entirety of their workload dedicated to dementia care coordination. Primary care dementia coordinators typically have a professional background as occupational therapist, nurse, or nurse assistant with specialist training in dementia and typically offer counseling, provide dementia education, information and support groups, and frequently act as dementia case managers.

A questionnaire was distributed among 47 participants in a seminar on dementia among ME groups at the 2018 Annual Conference of the Association of Dementia Coordinators in Denmark. In 2018, the Association of Dementia Coordinators in Denmark had 425 members. The questionnaire form was presented in a printed format, consisted of 10 questions, and took approximately 10 minutes to complete. The questionnaire items investigated different points in provision of post-diagnostic care and support in ME communities and the perceived challenges of solving this task. The questionnaire consisted of three main sections: cross-cultural resources, uptake of dementia care and support services, and dementia care and support in ME communities—general. The first section concerned cross-cultural resources available to dementia coordinators in the municipality they were employed and their professional experience, especially whether the respondent had experience of working with service users from the ME communities. The second section focused on the perceived influence of cultural and linguistic factors on the uptake post-diagnostic care and support services in ME communities. The third section focused on the dementia coordinator’s general perceptions of challenges and skills in providing post-diagnostic care and support to ME communities. The questionnaire form contained space for leaving comments. In the first section of the questionnaire, respondents were asked to give yes/no/don’t know responses regarding available cross-cultural resources. Otherwise four versions of five-point Likert scales were used throughout the questionnaire as appropriate. A pilot study evaluating the questionnaire was conducted with six collaborating dementia coordinators prior to initiation of the survey.

To analyze differences between geographic regions with different rates of people from ME communities with dementia, geographic regions were grouped into regions with a limited number of people from ME communities with dementia (Region Zealand, Region of Southern Denmark, Central Denmark Region and North Denmark Region) and a region with a more pronounced number of people from ME communities with dementia (Capital Region of Denmark). Regions with a limited number of people from ME communities with dementia were generally more thinly populated geographic regions consisting of larger rural as well as urban areas, whereas the Capital Region of Denmark mainly consists of densely populated urban areas.

Using SPSS statistical software (Version 22.0 SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), the responses from geographic regions with different rates of people from ME communities with dementia were compared. Fisher’s Exact Test or Pearson’s χ2 test was used to investigate the significance of differences in available cross-cultural resources. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to examine the significance of differences in responses concerning dementia care and support for ME communities. For ease of presentation, data from Likert scales are dichotomized in the presentation of the results leaving out neutral responses (sometimes) and “don’t know/not relevant” responses. p Value less than .05 (two-tailed) was considered significant.

Ethics

Prior to the survey, participants were provided written and oral information about the study and had the opportunity to ask additional questions. Participation was anonymous, voluntary, and without any economic incentive. According to the Danish legislation, survey studies are not considered health science research and are thus not evaluated or approved by the National Committee on Health Science Research. The study is part of a larger research project that was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (jnl no.: 2012–58-0004).

Results

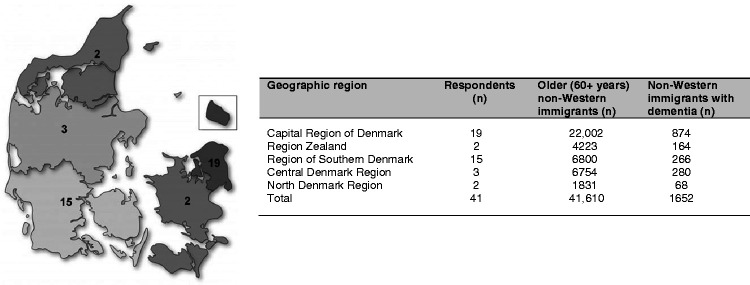

Of the 47 dementia coordinators invited to participate in the survey, 41 (87%) participants from all geographic regions of Denmark responded to the survey. The geographic distribution of responding dementia coordinators along with the number of older people from ME communities and the expected number of people with dementia across geographic regions are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Distribution of participating dementia coordinators. (a) Geographical distribution of respondents. The numbers in each geographic region denote the number of participating dementia coordinators from that region. (b) Number of respondents from each geographic region, as well as the number of older non-western immigrants and predicted number of non-western immigrants with dementia in each region based on 2018 population data from Statistics Denmark coupled with prevalence rates from the World Alzheimer Report 2015 (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2015).

Of the surveyed dementia coordinators, 39 (95%) had personal experience with service users from ME communities. Among them, 25 (64%) had been in contact with less than four service users from ME communities during the last year, while three (8%) reported having had contact to more than 10. Three respondents specifically commented that they generally found it hard to establish contact with the families who often preferred to take care of their older family member themselves without help from public services. The most common communities that dementia coordinators had experience of working with were immigrants and first-degree descendants from the Middle East (especially from Turkey and Iran) followed by immigrants from Eastern Europe (mainly from the former Yugoslavia and Poland) and Pakistan. Thirty (77%) dementia coordinators reported that, compared to ethnic Danish service users, they usually came in contact with service users from ME communities later in the course of the disease when they were in the moderate to severe stage of dementia.

Available cross-cultural resources

Among the surveyed dementia coordinators, 25 (61%) had access to translated dementia information material relevant to the ME communities they commonly worked with, 14 (34%) had colleagues with ME background they could consult when working with service users from the same community, 16 (39%) had access to the Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS) (Storey, Rowland, Basic, Conforti, & Dickson, 2004), which is the cognitive screening test recommended for cross-cultural assessment of dementia in Denmark, and nine (22%) had knowledge of specialized dementia care and support services for ME communities in their municipality. Five respondents from the Capital Region of Denmark specifically mentioned a public multicultural profiled nursing home in the region as a specialized service for ME communities.

Influence of ME background on dementia care and support services

The perceived influence of service users’ ME background on uptake of various dementia care and support services is illustrated in Table 1. Generally, uptake of services focusing on personal care and support, including home care and care and support provided in day centers, respite care and nursing homes, as well as food delivery services, and patient and carer education, were most frequently perceived to be affected by ME background, while uptake of services focusing on practical support, including installation and instruction in using aids, transport service, and handling of medicine by a home nurse were perceived to be least affected by ME background.

Table 1.

Influence of minority ethnic background on uptake of dementia care and support services (n = 39).

| Influenced by ethnic minority background, n (%) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Service uptake | Never/rarely | Often/always |

| Home nurse | 9 (24%) | 21 (55%) |

| Personal support and care | 3 (4%) | 30 (81%) |

| Practical support | 6 (16%) | 25 (73%) |

| Physical training/exercise | 3 (8%) | 23 (64%) |

| Practical/cognitive aids | 8 (23%) | 14 (40%) |

| Food service | 2 (6%) | 28 (78%) |

| Transport | 7 (20%) | 14 (40%) |

| Day center | 1 (3%) | 32 (84%) |

| Respite care | 1 (3%) | 30 (81%) |

| Senior housing | 2 (5%) | 23 (62%) |

| Nursing home | 1 (3%) | 25 (68%) |

| Patient counseling and education | 1 (3%) | 24 (63%) |

| Carer education and support groups | 1 (3%) | 27 (73%) |

The issues most dementia coordinators perceived to affect uptake of dementia care and support services were ME service users’ Danish language abilities, knowledge about dementia, and the lack of dementia services specifically tailored to the needs of ME communities. Religious issues and care workers’ attitude toward ME service users were least frequently reported to affect uptake of dementia care and support services (Table 2). Thirty-seven of the dementia coordinators (95%) generally found providing dementia care and support services to ME service users to be more challenging compared to ethnic Danish service users, and 20 (51%) generally found their municipality to have poor competencies at providing care and support in ME communities, while 38 (97%) generally found ME families to be more involved in provision of personal care and support compared to ethnic Danish families.

Table 2.

Issues influencing uptake of dementia care and support services (n = 39).

| Influence on uptake of dementia services, n (%) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Issues | Never/rarely | Sometimes/often |

| Service users’ religion | 3 (9%) | 18 (51%) |

| Service users’ linguistic abilities | 0 (0%) | 33 (89%) |

| Service users’ educational level | 3 (8%) | 22 (59%) |

| Service users’ knowledge about dementia | 0 (0%) | 31 (84%) |

| Service users’ attitude toward care workers | 1 (3%) | 23 (62%) |

| Care workers’ knowledge of patients’ culture | 1 (3%) | 26 (70%) |

| Care workers’ attitude toward minority ethnic service users | 7 (19%) | 16 (44%) |

| Suitability of available dementia services | 2 (6%) | 30 (83%) |

Comparison of regions with different rates of people from ME communities with dementia

Dementia coordinators in the geographic region with a more pronounced number of people from ME communities with dementia (i.e. the Capital Region of Denmark) were more likely to have access to the RUDAS (Fisher’s Exact Test, p = .029, and d = .77) and found providing dementia care and support for people from ME communities to be less challenging (U = 247, p = .05, and d = 67) compared to dementia coordinators employed in other geographic regions. No significant differences were found in other available cross-cultural resources or responses concerning dementia care and support in ME communities.

Discussion

This study examined barriers to accessing post-diagnostic care and support in ME communities from the perspective of primary care dementia coordinators in Denmark. We found that most dementia coordinators had regular but limited contact with new ME service users throughout the year. Uptake of most post-diagnostic services were perceived to be influenced by service users’ ME background, and the dementia coordinators generally considered providing care and support for the service users to be challenging due to communication difficulties, poor knowledge about dementia among ME service users, inadequate cultural sensitivity of care workers, and a lack of suitable dementia services for ME communities. Strategies for overcoming cultural and linguistic barriers were generally sparse, and only one-fifth of the participants knew of specialized care and support services for people from ME communities in their municipality. Considering the apparent lack of service use, not surprisingly, ME families were generally believed to be more involved in provision of personal care and support compared to ethnic Danish families.

Although people from ME communities with dementia are prevalent in all Danish geographic regions, the dementia coordinators generally did not come into contact with more than a couple of service users from ME communities a year, and this could not be explained by service users accessing more suitable care and support services elsewhere, including private services. No differences were found between geographic regions with a limited, relative to more pronounced, number of people from ME communities with dementia. Dementia coordinators in the present study mainly reported working with ME service users originating from the Middle East, East Europe, and South Asia, who were generally in the moderate to severe stage of their dementia disorder at the point they met them. As discussed in the previous reports, this may be an indication that people from these ME communities are less able to access dementia care and support services, and when they do so, they access these services at a later stage of the disease (Cooper et al., 2010; Hailstone, Mukadam, Owen, Cooper, & Livingston, 2017; Mukadam, Cooper, Basit, & Livingston, 2011a; Næss & Moen, 2015; Pham et al., 2018; Segers et al., 2013; van Wezel et al., 2016). Whereas some barriers to accessing post-diagnostic dementia care and support seem to be associated with specific cultural norms and values in predominantly family-oriented Middle Eastern, East European, and South Asian ME communities, others seem to represent more general barriers faced by minority groups in a society where only mainstream services tailored to the majority culture and language are available.

The issues perceived to affect uptake of dementia care and support services by primary care dementia coordinators in the present study were generally in line with previous research on barriers to help seeking for dementia. On one hand, there may be barriers associated with reactions to cognitive decline among ME groups, including normalization of symptoms (i.e. seeing memory problems as a normal part of old age), stigma, shame, and cultural pressure to care for family members (Berdai Chaouni & De Donder, 2018; Denktas, Koopmans, Birnie, Foets, & Bonsel, 2009; Kenning et al., 2017; Mukadam et al., 2011b; Nielsen & Waldemar, 2016; Næss & Moen, 2015; Sagbakken, Spilker, & Ingebretsen, 2018). On the other hand, there may be healthcare-associated barriers, including lack of clarity about the services available to people with dementia, language barriers, and lack of choice when seeking formal care and support services with available services often lacking cultural awareness and diversity for interacting with different cultural communities (Berdai Chaouni & De Donder, 2018; Kenning et al., 2017; Mukadam et al., 2011b; Næss & Moen, 2015; Sagbakken et al., 2018). Although considered less challenging in geographic regions with a more pronounced number of people from ME communities with dementia, almost all participating dementia coordinators (95%) reported providing post-diagnostic care and support for ME communities to be more challenging compared to ethnic Danish service users, and half of the participants (51%) found their municipality to have poor competencies at providing these services.

In line with several other studies (Berdai Chaouni & De Donder, 2018; Sagbakken et al., 2018; van Wezel et al., 2016), the dementia coordinators frequently found uptake of the offered post-diagnostic care and support services to be influenced by service users’ ME background, and 97% generally found the families to be more involved in personal care and support of the person with dementia. Although the comments from some dementia coordinators seem to reflect an assumption that certain ME groups prefer to “look after their own” and do not want any support, some studies indicate that this may not always be true as practices linked to provision of care within the family and the use of formal care and support may be gradually changing as a result of changing family structures, more women taking up paid employment outside the home, and different perspectives on care, especially amongst younger generations (Bhattacharyya & Benbow, 2013; Lawrence, Murray, Samsi, & Banerjee, 2008; van Wezel et al., 2016). There was an indication that uptake of services focusing on practical support were less affected by ME background compared to services focusing on personal care and support, as well as participation in patient and carer education and support groups. This is partly supported by a study analyzing data from Copenhagen social care registries which found that, compared to ethnic Danes, ME older people (65+ years) with at least 10 years of residence in Denmark were 50% less likely to utilize practical support services, whereas they were 77% less likely to utilize nursing home services (Hansen & Siganos, 2013). This seems to suggest that, to some families, services that support provision of care and support for the person with dementia within the context of the family may be more culturally appropriate than services involving entrusting personal care and support to outsiders, i.e. healthcare professionals in home care services, day centers, respite care, and nursing homes.

The lower uptake of post-diagnostic care and support services may, in part, be explained by a strong impact of cultural norms within ME groups. On one hand, a strong sense of familial responsibility and a tendency to consider problems associated with cognitive impairment as a personal or family matter may pose a barrier for seeking help from outside sources, as help seeking from formal services may be seen as disrespectful of a person’s autonomy or a failure to fulfill one’s religious responsibility to help older family members (Antelius & Kiwi, 2015; Berdai Chaouni & De Donder, 2018; Kenning et al., 2017; Næss & Moen, 2015; Sagbakken et al., 2018; van Wezel et al., 2016). At the same time, stigma around mental health and dementia (perceiving dementia as a form of “insanity”) may lead to anxiety and reluctance to letting other people come into the home to provide care or support or talking about family matters with strangers in patient and carer education and support groups (Antelius & Kiwi, 2015; Berdai Chaouni & De Donder, 2018; Kenning et al., 2017; Sagbakken et al., 2018). Also, there is often little choice within mainstream health- and social care systems, and matching of professional carers by language, religion, or gender may be hard to achieve (Rosendahl, Soderman, & Mazaheri, 2016; Soderman & Rosendahl, 2016). This may result in care options that are considered unacceptable in certain communities (Antelius & Kiwi, 2015; Næss & Moen, 2015).

A limitation of the present findings is related to the questionnaire study design, which relies on self-report of challenges related to own practice but does not involve objective measures. Thus, the findings represent the dementia coordinators’ perceptions only. This may have led to over- or under-estimations in the responses and the risk that responses are biased by social desirability, that is, responses, to some extent, portrays desired rather than true practices. Another limitation is the purposive sampling of primary care dementia coordinators participating in a seminar on dementia among ME groups, who were assumed to have a special interest in, as well as experience with, the topic. Consequently, the results may not be generalized to all Danish primary care dementia coordinators involved in provision of care and support services for people from ME groups. Also, the limited number of survey participants inevitably resulted in low statistical power, increasing the risk of type II errors (“false negative” findings). However, the strategy of purposive sampling of a smaller but engaged group of primary care dementia coordinators was chosen to ensure that participants possessed the knowledge and experience required to answer the survey questions sufficiently. A survey among all Danish primary care dementia coordinators would ideally have resulted in a more representative national sample and increased statistical power. However, the approach was dismissed as most Danish primary care dementia coordinators have little or no experience with ME service users, which was expected to result in a very low response rate and to increase the risk of participants responding to survey questions based on their assumptions rather than experience. Thus, we considered the perceptions of dementia coordinators with experience and knowledge from working with ME service users would give the best impression of barriers to post-diagnostic care and support in ME communities in Denmark, which is an area that has not yet been properly described. The main strengths of the study were the high response rate to the survey (87%), that the findings represent the perceptions of dementia coordinators with practice-oriented experience of working with ME families and communities, and the fact that the sample covered respondents employed in municipalities across all geographic regions of Denmark with different degrees of experience of working with ME service users well represented in the sample.

In conclusion, the present study suggests that, even after a diagnosis, people from ME groups may choose not to access available dementia care and support services. On one hand, research suggests this may be linked to strong cultural norms, including familial responsibility for the care of older family members and stigma associated with mental illness and dementia. On the other hand, the available formal services are rarely tailored to the specific needs of ME service users and may be considered inadequate or unacceptable. Consequently, there is a need to develop methods and models for post-diagnostic care and support that include cultural awareness and diversity for interacting with different cultural communities. Preferably, these models should include both services that support the families in providing good care within the family setting as well as culturally appropriate formal care solutions.

Biography

T Rune Nielsen, neuropsychologist, PhD, is a postdoctoral fellow at the Danish Dementia Research Centre, University of Copenhagen, Rigshospitalet. His main research interests are dementia in minority ethnic groups and low- and middle-income countries as well as cross-cultural neuropsychological assessment, but he has contributed to a range of clinical and epidemiological research projects at the Danish Dementia Research Centre. He is active as a clinical and academic supervisor and a clinical researcher in Denmark and internationally.

Dorthe Nielsen, RN, MHS, PhD, is an associate professor in cross cultural nursing. Her research interest involves cross cultural nursing, patient education, patients’ perspectives in everyday life, adherence to treatment, and collaborative research using both qualitative and quantitative methods. In Denmark, she has started a network and education program for allied health professionals aiming to increase knowledge and cultural competences from a multidisciplinary point of view. She is a member of the board of transcultural nursing in Denmark.

Gunhild Waldemar, MD, DMSc, FEAN, is a professor of clinical neurology at the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences and chairman of the Danish Dementia Research Centre at the Department of Neurology, Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen. Her research interests are clinical and epidemiological research and intervention studies in Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Prof. Waldemar serves as a board member of the Medical and Scientific Advisory Panel of Alzheimer’s Disease International, and the Expert Advisory Panel of Alzheimer Europe.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by the VELUX FOUNDATION (grant number 00017257), which had no role in the formulation of research questions, choice of study design, data collection, data analysis or decision to publish. The Danish Dementia Research Centre is supported by the Danish Ministry of Health.

Contributor Information

T Rune Nielsen, Danish Dementia Research Centre, University of Copenhagen, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Dorthe S Nielsen, Migrant Health Clinic, Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark; Centre for Global Health, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark; Health Sciences Research Center, University College Lillebælt, Odense, Denmark.

Gunhild Waldemar, Danish Dementia Research Centre, University of Copenhagen, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark.

References

- Alzheimer's Disease International (2015). World Alzheimer Report 2015: The Global Impact of Dementia. An analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. London: Alzheimers Disease International (ADI).

- Antelius E., Kiwi M. (2015). Frankly, none of us know what dementia is: Dementia caregiving among Iranian immigrants living in Sweden. Care Management Journals, 16, 79–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APPG (All-Party Parliamentary Group) on Demntia. (2013). Dementia does not discriminate. The experience of black, Asian and minority ethnic communities. London: Alzheimer’s Society.

- Berdai Chaouni S., De Donder L. (2018). Invisible realities: Caring for older Moroccan migrants with dementia in Belgium. Dementia (London), 1471301218768923. Epub ahead of print 13 April 2018. DOI: 10.1177/1471301218768923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya S., Benbow S. M. (2013). Mental health services for black and minority ethnic elders in the United Kingdom: A systematic review of innovative practice with service provision and policy implications. International Psychogeriatrics, 25, 359–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C., Tandy A. R., Balamurali T. B., Livingston G. (2010). A systematic review and meta-analysis of ethnic differences in use of dementia treatment, care, and research. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18, 193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denktas S., Koopmans G., Birnie E., Foets M., Bonsel G. (2009). Ethnic background and differences in health care use: A national cross-sectional study of native Dutch and immigrant elderly in the Netherlands. International Journal for Equity in Health, 8, 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz E., Kumar B. N., Engedal K. (2015). Immigrant patients with dementia and memory impairment in primary health care in Norway: A national registry study. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 39, 321–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hailstone J., Mukadam N., Owen T., Cooper C., Livingston G. (2017). The development of Attitudes of People from Ethnic Minorities to Help-Seeking for Dementia (APEND): A questionnaire to measure attitudes to help-seeking for dementia in people from South Asian backgrounds in the UK. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32, 288–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen E. B., Siganos G. (2013). Ældre danskeres og indvandreres brug af pleje- og omsorgsydelser [Older Danes’ and immigrants’ use of care services]. Copenhagen, Denmark: AKF, Anvendt KommunalForskning. [Google Scholar]

- Kenning C., Daker-White G., Blakemore A., Panagioti M., Waheed W. (2017). Barriers and facilitators in accessing dementia care by ethnic minority groups: A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Psychiatry, 17, 316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence V., Murray J., Samsi K., Banerjee S. (2008). Attitudes and support needs of Black Caribbean, south Asian and White British carers of people with dementia in the UK. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 193, 240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukadam N., Cooper C., Basit B., Livingston G. (2011. a). Why do ethnic elders present later to UK dementia services? A qualitative study. International Psychogeriatrics, 23, 1070–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukadam N., Cooper C., Livingston G. (2011. b). A systematic review of ethnicity and pathways to care in dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26, 12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen T. R., Antelius E., Spilker R. S., Torkpoor R., Toresson H., Lindholm C., … Nordic Research Network on Dementia and Ethnicity. (2015). Dementia care for people from ethnic minorities: A Nordic perspective. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30, 217–218. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen T. R., Vogel A., Phung T. K., Gade A., Waldemar G. (2011). Over- and under-diagnosis of dementia in ethnic minorities: A nationwide register-based study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26, 1128–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen T. R., Waldemar G. (2016). Knowledge and perceptions of dementia and Alzheimer's disease in four ethnic groups in Copenhagen, Denmark. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31, 222–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Næss A., Moen B. (2015). Dementia and migration: Pakistani immigrants in the Norwegian welfare state. Ageing & Society, 35, 1713–1738. [Google Scholar]

- Pham T. M., Petersen I., Walters K., Raine R., Manthorpe J., Mukadam N., Cooper C. (2018). Trends in dementia diagnosis rates in UK ethnic groups: Analysis of UK primary care data. Clinical Epidemiology, 10, 949–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosendahl S. P., Soderman M., Mazaheri M. (2016). Immigrants with dementia in Swedish residential care: An exploratory study of the experiences of their family members and Nursing staff. BMC Geriatrics, 16, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagbakken M., Spilker R. S., Ingebretsen R. (2018). Dementia and migration: Family care patterns merging with public care services. Qualitative Health Research, 28, 16–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segers K., Benoit F., Colson C., Kovac V., Nury D., Vanderaspoilden V. (2013). Pioneers in migration, pioneering in dementia: First generation immigrants in a European metropolitan memory clinic. Acta Neurologica Belgica, 113, 435–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderman M., Rosendahl S. P. (2016). Caring for ethnic older people living with dementia – Experiences of nursing staff. Journal of Cross Cultural Gerontology, 31, 311–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevnsborg L., Jensen-Dahm C., Nielsen T. R., Gasse C., Waldemar G. (2016). Inequalities in access to treatment and care for patients with dementia and immigrant background: A Danish Nationwide Study. Journal of Alzheimers Disease, 54, 505–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey J. E., Rowland J. T., Basic D., Conforti D. A., Dickson H. G. (2004). The Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS): A multicultural cognitive assessment scale. International Psychogeriatrics, 16, 13–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wezel N., Francke A. L., Kayan-Acun E., Ljm Deville W., van Grondelle N. J., Blom M. M. (2016). Family care for immigrants with dementia: The perspectives of female family carers living in The Netherlands. Dementia (London), 15, 69–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]