Abstract

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a serious microvascular complication of diabetes. Gambogic acid has been reported to have anti-inflammatory effect. However, the effect of GA on inflammatory response of ARPE-19 cells remains unclear. In our study, ARPE-19 cells were stimulated by palmitic acid (PA) induction in the presence of 30 mM glucose and then treated with 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, or 20 μM GA. CCK-8 assay showed that cell viability was increased by GA treatment at doses of 0.5, 1, and 2 μM instead of higher doses. ELISA analysis found that GA dose-dependently reduced the production of pro-inflammatory mediators TNF-α and IL-1β. Western blot indicated that GA downregulated the expression of NLRP3 inflammasome components including TXNIP, NLRP3, ASC, cleaved-caspase-1, and cleaved-IL-1β in a dose-dependent manner. In addition, Western blot and immunofluorescence analysis suggested that GA effectively increased the protein level of nuclear factor E2-related factor-2 (Nrf2). RT-qPCR showed that GA significantly increased the mRNA levels of Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and NADPH:quinone oxidoreductase1 (NQO1). Furthermore, Nrf2 siRNA transfection confirmed the above effects of GA. In total, subtoxic doses of GA significantly flattened the inflammatory response induced by HG and PA in ARPE-19 cells via modulating the Nrf2 signaling pathway.

Keywords: Retinal pigment epithelium, Inflammatory response, Gambogic acid, Palmitic acid, Nuclear factor E2-related factor-2 (Nrf2)

Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a debilitating microvascular complication of diabetes mellitus and is one of the leading causes of blindness in patients with diabetes (Gverovic Antunica et al. 2019; Yau et al. 2012). In the USA, the prevalence rate of DR and vision-threatening DR among adults with diabetes was approximately 28.5% and 4.4%, respectively (Zhang et al. 2010). At present, the progress with laser therapy, anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents, and corticosteroids has been made in the diagnosis of DR, but there are still some limitations (Singer et al. 2016). With the prevalence of diabetes expected to continue to rise, more and more effective treatments for DR are needed.

Retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) is the specialized epithelium lying in the outermost layer of the neural retina, which can produce inflammatory mediators to serve as the first line of defense against danger (Arimura et al. 2009). RPE cells are considered to be involved in the progression of DR (Strauss 2005). In past studies, investigators have identified a variety of physiologic and molecular changes related to inflammation in the retinas or vitreous humor of diabetic animals and patients (Funatsu et al. 2009; Miller et al. 1994). Inflammation plays a prominent role in the occurrence and development of DR, and the inhibition of inflammation can affect the progression of retinal alterations in experimental diabetes in rats (Joussen et al. 2001). In previous studies, palmitic acid (PA) has been found to induce injury in retinal ganglion cells (Yan et al. 2016). PA can aggravate inflammatory response of Müller cell, pancreatic acinar cell, and Kupffer cells (Cai et al. 2017; Capozzi et al. 2018; Wu et al. 2016a, b).

Gamboge, a dry resin of Chinese medicine Garcinia hanburyi, has a long history of use as traditional medicine, as Garcinia cold, pickle, sim, astringent, and toxic and has the effects of hemostasis, detoxification, and killing insects (Palempalli et al. 2009; Yang et al. 2013a). Gambogic acid (GA) is the main effective constituent of gamboge resin, with the functions of anti-angiogenesis, anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and detoxification (Liu et al. 2019; Palempalli et al. 2009). Increasing studies have shown that GA can inhibit angiogenesis in human HUVEC cell line and zebrafish model (Yang et al. 2013b; Youns et al. 2018), and promote the activation of oxidative stress-dependent caspase to regulate apoptosis and autophagy in bladder cancer cells (Ishaq et al. 2014). GA has been reported to improve diabetes-induced proliferative retinopathy in HG-treated retinal endothelial RF/6A cells and streptozocin-induced mice (Cui et al. 2018). GA can induce heme oxygenase-1 by nuclear factor E2-related factor-2 (Nrf2) signaling and reduce inflammatory response through inhibiting the activation of the nuclear factor-kappa B and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in lipopolysaccharide-activated RAW264.7 cells (Ren et al. 2019). However, the effect of GA on inflammatory response of RPE cells induced by high glucose (HG) and PA remains unclear, which needs to be further elucidated.

In our study, we further investigated the relative biochemical mechanisms of the beneficial effect of GA on ARPE-19 cells and confirmed that its protective effect was related to the anti-inflammatory effect of GA.

Materials and methods

Drugs and antibodies

DMEM/F12 cell culture medium was purchased from Procell Life Science and Technology Co., Ltd. (PM150312, Wuhan, China). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was from Hyclone (SH30084.03, Logan, USA). GA (CAS: 2752-65-0) and glucose were obtained from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (G101480 and G116307, Shanghai, China). PA was purchased from Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd. (SP8060, Beijing, China). The primary antibodies used in our study were list as below: thioredoxin interacting protein (TXNIP; A9342, Abclonal, China), NLRP3 (A5652, Abclonal, China), apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC; A1170, Abclonal, China), caspase-1 (ab179515, Abcam, China), IL-1β (#12703, CST, USA), Nrf2 (16396-1-AP, Proteintech, China), Histone H3 (GTX122148, Gene Tex, USA), and GAPDH (60004-1-Ig, Proteintech, China).

Cell culture and treatment

ARPE-19, a human RPE cell line, was purchased from Procell Life Science and Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China) and cultured in DMEM/F12 cell culture medium supplemented with 10% FBS in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C.

ARPE-19 cells were incubated with normal glucose (NG; 5.5 mM glucose) or HG (30 mM glucose) for 24 h. Then, the cells were treated with PA (50 μM, 100 μM, 200 μM, 400 μM) for 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h, respectively. Subsequently, in the presence of HG, ARPE-19 cells were treated with 200 μM PA and GA (0.5 μM, 1 μM, 2 μM, 5 μM, 10 μM, 20 μM) for 24 h. In addition, ARPE-19 cells with Nrf2 siRNA or NC siRNA transfection were incubated with NG or HG for 24 h and then treated with PA and GA for another 24 h.

Cell counting kit-8 assay

The viability of ARPE-19 cells was determined with a Cell Counting Kit-8 detection kit (CCK-8; C0037, Beyotime, China) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, the cells were seeded into 96-well plates at the density of 5 × 103 cells per well. At the indicated time point, 10 μL of CCK-8 solution was added and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm under a microplate reader (ELX-800, BioTek, USA).

ELISA analysis

Inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor-α) and IL-1β (interleukin-1β) levels in cell supernatant, were measured by ELISA kits (EK182 and EK101B, MultiSciences, China) as per instructions of the manufacturer.

Western blot analysis

Total proteins were extracted from ARPE-19 cells in lysis buffer (R0010, Solarbio, China). The protein concentration was quantified using the BCA protein assay kit (PC0020, Solarbio, China). Then, the protein samples were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (IPVH00010, Millipore, USA). After blocking with 5% skim milk powder for 1 h, the membranes were incubated with the primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. After that, the membrane was washed with TBST, and the secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The bands were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) system and the gray densities were quantified with the Gel-Pro-Analyzer software.

Immunofluorescence staining

ARPE-19 cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 solution (ST795, Beyotime, China) for 30 min at room temperature. After blocking with goat serum for 15 min, the sections were incubated with primary anti-Nrf2 antibody (WL02135, Wanleibio, China) overnight at 4 °C, and then incubated with Cy3 labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (A0516, Beyotime, China) for 1 h at room temperature. All sections were counterstained with DAPI (D106471-5 mg, Aladdin, China) and observed under a fluorescence microscope (DP73, Olympus, Japan) at × 400 magnification.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA from ARPE-19 cells was isolated with a RNA extraction kit (DP419, Tiangen, China) and reverse transcribed using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (NG212, Tiangen, China). Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed using SYBR Green PCR kit (SY1020, Solarbio, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. GAPDH was utilized as a reference gene. The primer sequences used for RT-qPCR were as follows: heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), 5′-TTTGAGGAGTTGCAGGAGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGGACCCATCGGAGAAGC-3′ (reverse); NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), 5′-ATGGGAGGTGGTGGAGTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTTTCAGAATGGCAGGGA-3′ (reverse); GAPDH, 5′-GACCTGACCTGCCGTCTAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGGAGTGGGTGTCGCTGT-3′ (reverse). The relative quantification was determined and analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Mahmoudian-Sani et al. 2018).

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed three times independently. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to analyze the values among different groups by GraphPad Prism software. A p value of less than 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Results

The effect of HG and PA combination on inflammatory response in ARPE-19 cells

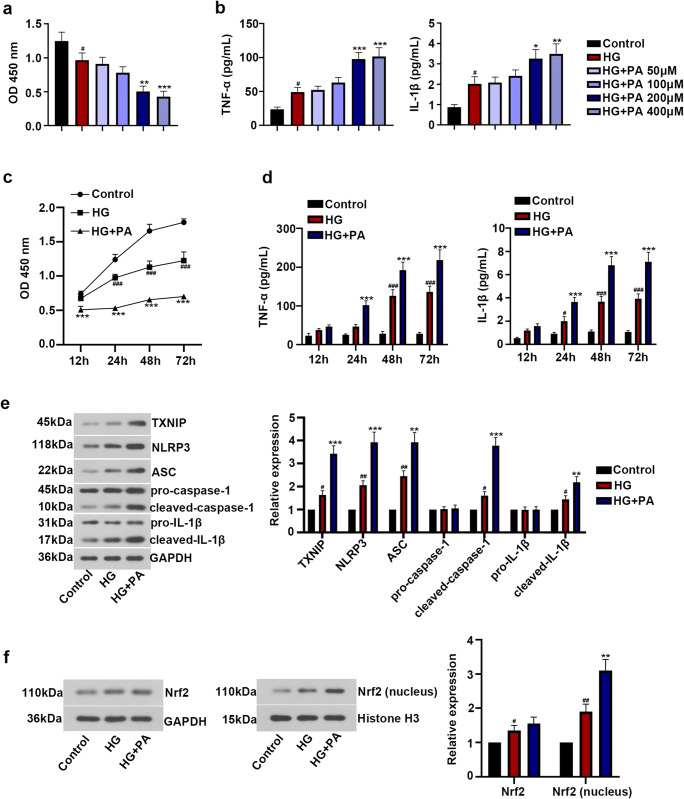

A previous study has shown that co-treatment of HG with PA can cause Müller cell inflammatory response (Capozzi et al. 2018). Here, the results of CCK-8 and ELISA demonstrated that treatment of HG reduced cell viability and induced the release of TNF-α, IL-1β. Besides, co-treatment with HG and PA significantly enhanced the reduction of cell viability and the induction of TNF-α, IL-1β in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1a–d). Moreover, Western blot analysis indicated that HG treatment upregulated the protein expression levels of TXNIP, NLRP3, ASC, cleaved-caspase-1, and cleaved-IL-1β, while there was no significant change in the expression of pro-caspase-1, pro-IL-1β, and total Nrf2. HG treatment also potentiated Nrf2 translocation to the nucleus. More importantly, the combination of HG and PA could significantly enhance the above effects of HG in ARPE-19 cells (Fig. 1e, f). These results showed that HG and PA co-treatment remarkably induced inflammatory response in ARPE-19 cells.

Fig. 1.

Co-treatment of high glucose with palmitic acid–induced inflammatory response of ARPE-19 cells. Human retinal pigment epithelial ARPE-19 cells were incubated with NG (5.5 mM glucose) or HG (30 mM glucose) for 24 h, and then treated with PA (50 μM, 100 μM, 200 μM, 400 μM) for 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h, respectively. a Cell viability after PA treatment at different concentrations was measured using CCK-8 assay. b Levels of TNF-α and IL-1β after PA treatment at different concentrations were detected by ELISA kit. c After 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h treatment, cell viability was measured with CCK-8 assay. d After 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h treatment, levels of TNF-α and IL-1β were detected by ELISA kit. e Relative expression of TXNIP, NLRP3, ASC, caspase-1, and IL-1β was assessed by Western blot. f The expression of Nrf2 in total and nucleus was detected by Western blot. The data was presented as means ± SD (n = 3). #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. Control group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. HG group

The effect of GA on HG- and PA-induced inflammatory response in ARPE-19 cells

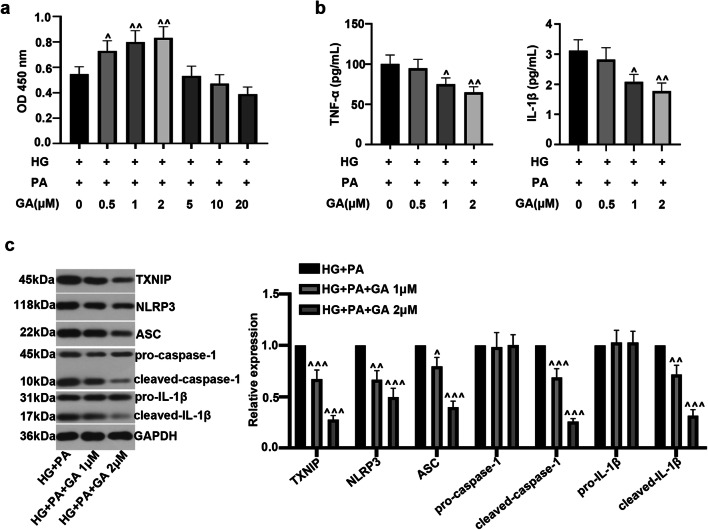

To evaluate the effect of GA on HG- and PA-induced inflammatory response in ARPE-19 cells, CCK-8, ELISA, and Western blot assays were performed. As illustrated in Fig. 2a, 0.5, 1, and 2 μM doses instead of higher doses (5, 10, and 20 μM) of GA could obviously increase the viability of ARPE-19 cells compared with the HG and PA treatment. To some extent, compared with the HG and PA challenge group, GA dose-dependently decreased the production of inflammatory factors TNF-α and IL-1β (Fig. 2b). In addition, GA could significantly reduce TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome activation, accompanied by the downregulation of the expression of TXNIP, NLRP3, ASC, cleaved-caspase-1, and cleaved-IL-1β in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2c). All results showed that GA attenuated HG and PA-caused inflammatory response in ARPE-19 cells.

Fig. 2.

Effect of gambogic acid on high glucose– and palmitic acid–induced inflammatory response in ARPE-19 cells. ARPE-19 cells were incubated with HG for 24 h, and then treated with PA (200 μM) and GA (0.5 μM, 1 μM, 2 μM, 5 μM, 10 μM, 20 μM) for another 24 h. a CCK-8 assay was performed to detect cell viability. b TNF-α and IL-1β levels were measured by ELISA kit. c Relative expression of TXNIP, NLRP3, ASC, caspase-1, and IL-1β was assessed by Western blot. The data was presented as means ± SD (n = 3). ^p < 0.05, ^^p < 0.01, ^^^p < 0.001 vs. HG + PA group

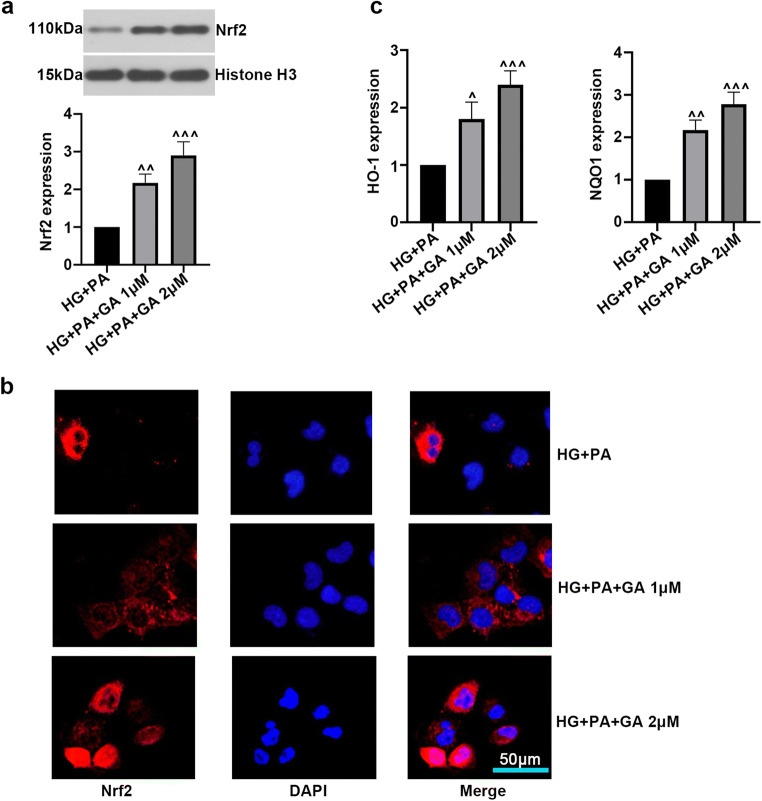

The effect of GA on Nrf2 signaling pathway

Nrf2 plays pivotal role in inflammatory response and inhibits anti-inflammatory progression. We further assessed the effect of GA on Nrf2 signaling pathway caused by treatment of HG and PA in ARPE-19 cells. Western blot and immunofluorescence analysis suggested that GA obviously increased the protein level of nuclear Nrf2 (Fig. 3a, b). Moreover, RT-qPCR showed that GA treatment activated Nrf2/HO-1 transcription, as reflected by increased HO-1 and NQO1 levels (Fig. 3c). The above results indicated that GA might contribute to the activation of Nrf2/ HO-1/NQO1 signaling pathway in HG- and PA-induced ARPE-19 cells.

Fig. 3.

Effect of gambogic acid on Nrf2 signaling pathway. ARPE-19 cells were incubated with HG for 24 h, and then treated with PA (200 μM) and GA (1 μM, 2 μM) for another 24 h. a Nrf2 level in nuclear was detected by Western blot. b The expression and cellular localization of Nrf2 were evaluated with immunofluorescence staining. c The mRNA expression of HO-1, NQO1 was detected by RT-qPCR. The data was presented as means ± SD (n = 3). ^p < 0.05, ^^p < 0.01, ^^^p < 0.001 vs. HG + PA group

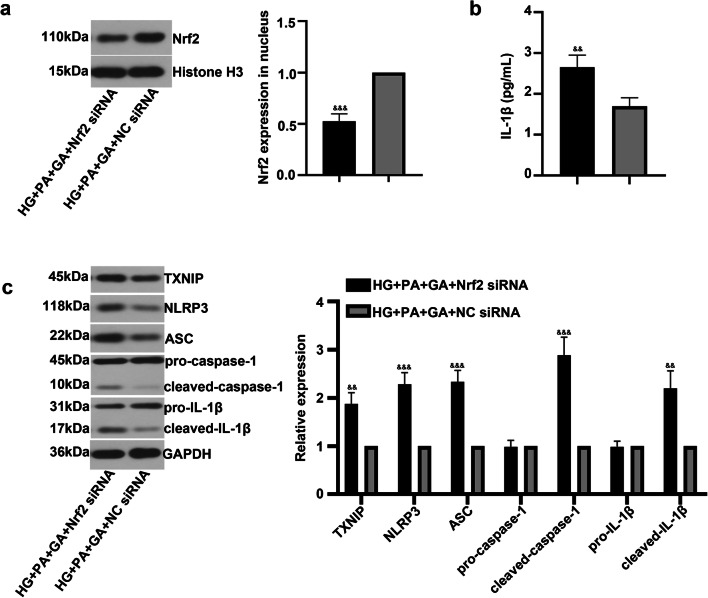

Nrf2 silencing abrogates the effect of GA in ARPE-19

To further verify the role of GA in inflammatory response through regulating Nrf2 signaling pathway, we examined the effects of co-administration of GA and Nrf2 siRNA under HG and PA conditions. As shown in Fig. 4a, Nrf2 siRNA reduced Nrf2 expression compared with NC siRNA transfection. ELISA result revealed a significant increase in IL-1β level by transfection of Nrf2 siRNA (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, the inhibition of Nrf2 induced the expression of TXNIP, NLRP3, ASC, cleaved-caspase-1, and cleaved-IL-1β (Fig. 4c), which confirmed the beneficial effect of GA on inflammatory response of ARPE-19 cells.

Fig. 4.

Nrf2 siNRA restrained the protective effect of gambogic acid on ARPE-19 cells. ARPE-19 cells were transfected with Nrf2 siRNA, followed by incubation with was HG for 24 h, and then treated with PA (200 μM) and GA (2 μM) for another 24 h. a Western blot was performed to detect Nrf2 level in nuclear. b IL-1β level was measured by ELISA kit. c Relative protein expression of TXNIP, NLRP3, ASC, caspase-1, and and IL-1β was evaluated by Western blot. The data was presented as means ± SD (n = 3). &&p < 0.01, &&&p < 0.001 vs. HG + PA + GA + NC siRNA group

Discussion

In the present study, a novel observation revealed that inflammatory response could be induced in ARPE-19 cells under both HG and PA conditions. At sub-cytotoxic levels, GA suppressed the production of TNF-α and IL-1β and the expression levels of TXNIP, NLRP3, ASC, caspase-1, and IL-1β as well as promoted the activation of Nrf2 signaling pathway in ARPE-19 cells treated by HG and PA.

In human cancer cells, GA exhibits its anti-proliferative and anti-cancer effects (Li et al. 2019; Wu et al. 2016a, b; Youns et al. 2018). In diabetes-induced RF/6A cells, GA decreases cell proliferation and retinal angiogenesis (Cui et al. 2018). Moreover, GA inhibits inflammatory response in human keratinocyte HaCaT cells and HUVEC cells, and HC11 mammary epithelial cells (Tang et al. 2020; Wen et al. 2014). However, the effect of GA on inflammatory response of ARPE-19 cells needs to be further illustrated. Inflammation is regarded as a critical contributor for the pathogenesis and severity of human DR (Youngblood et al. 2019). We showed that PA in combination with HG resulted in inflammatory response of ARPE-19 cells, while there was a minor effect in the absence of PA treatment. In this context, we explored the role of GA and a possible molecular mechanism in HG- and PA-induced ARPE-19 cells. Our findings demonstrated that GA remarkably increased cell viability. As demonstrated by previous studies (Fu et al. 2018; Ren et al. 2019), GA can stimulate the release of pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 by activating inflammatory-related pathway. However, although GA has been found to have anti-inflammatory effect, it is toxic to cells, so appropriate concentrations should be screened to ensure safe use (Cao et al. 2010). We found that GA with low cytotoxicity significantly suppressed the excessive production of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in ARPE-19 cells stimulated by HG and PA.

Moreover, we presented the effect of GA on inflammasome NLRP3 activation. Inflammasomes consist of a central protein, an adaptor protein ASC and a caspase-1 protein (Yin et al. 2017). NLRP3 inflammasome can be activated under HG condition in ARPE-19 cells (Shi et al. 2015). Upon the activation of TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasomes, caspase-1 induces the production of cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18 (Devi et al. 2012; Martinon et al. 2002). The inhibition of TXNIP/NLRP3 pathway activation is beneficial to prevent retinal vascular damage (Lu et al. 2018). In our study, GA applied at subtoxic doses could decrease the expression of TXNIP, NLRP3, ASC, caspase-1, and IL-1β in HG- and PA-induced ARPE-19 cells. All above observations indicated that the protection of GA against HG- and PA-mediated inflammatory response in ARPE-19 cells may be achieved by inactivating the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Notably, this is the first finding showing the potential effect of GA on NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Furthermore, Nrf2 is a crucial redox-sensitive transcription factor in cellular homeostasis that can modulate anti-inflammatory responses (Dinkova-Kostova and Abramov 2015; Itoh et al. 2015). Nrf2 activation promotes the expression of downstream HO-1 and NQO1, thereby restraining the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in ARPE-19 cells (Mao et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2017). A previous study enunciated that GA induces Nrf2 activation and inhibits inflammatory response in RAW264.7 cells triggered by LPS (Ren et al. 2019). Consistent with previous studies, the results of our study demonstrated that subtoxic doses of GA treatment–induced HO-1 and NQO1 expression and accelerated the Nrf2 nuclear transport. Then, to further verify the function of Nrf2 in the beneficial effects of GA on DR, ARPE-19 cells were transfected with Nrf2 siRNA to silence Nrf2 expression. Nrf2 silencing verified the above changes. These results were in line with previous reports, indicating that the anti-inflammatory effect of GA might be associated with the activation of Nrf2 signaling pathway in HG and PA-injured ARPE-19 cells. However, further researches are necessary for clarifying this assumption.

Limitation of our current research is that we mainly explored the effect of GA on ARPE-19 cells, while it is worth investigating in primary RPE cells, Müller cells, and other retinal cells. In addition, lack of exploration of diabetic animals is also our limitation. Thus, these studies should be carried out in the near future.

In conclusion, we found that GA exerts an anti-inflammatory role in ARPE-19 cell inflammatory response exposed to HG and PA, which may be correlated with the activation of Nrf2 signaling pathway. These novel findings indicated the potential value of GA on DR may be related to its anti-inflammatory effect and the implications for further elucidating the pathogenesis of DR.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Arimura N, Ki-i Y, Hashiguchi T, Hawahara K, Biswas KK, Nakamura M, Sonoda Y, Yamakiiri K, Okubo A, Sakamoto T, Maruyama I. Intraocular expression and release of high-mobility group box 1 protein in retinal detachment. Lab Investig. 2009;89:278–289. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai C, Zhu X, Li P, Li J, Gong J, Shen W, He K. NLRP3 deletion inhibits the non-alcoholic steatohepatitis development and inflammation in Kupffer cells induced by palmitic acid. Inflammation. 2017;40:1875–1883. doi: 10.1007/s10753-017-0628-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L, Liu H, Lam DS, Yam GH, Pang CP. In vitro screening for angiostatic potential of herbal chemicals. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:6658–6664. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capozzi ME, Giblin MJ, Penn JS. Palmitic acid induces Muller cell inflammation that is potentiated by co-treatment with glucose. Sci Rep. 2018;8:5459. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23601-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J, Gong R, Hu S, Cai L, Chen L. Gambogic acid ameliorates diabetes-induced proliferative retinopathy through inhibition of the HIF-1alpha/VEGF expression via targeting PI3K/AKT pathway. Life Sci. 2018;192:293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devi TS, Lee I, Huttemann M, Kumar A, Nantwi KD, Singh LP. TXNIP links innate host defense mechanisms to oxidative stress and inflammation in retinal Muller glia under chronic hyperglycemia: implications for diabetic retinopathy. Exp Diabetes Res. 2012;2012:438238–438219. doi: 10.1155/2012/438238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinkova-Kostova AT, Abramov AY. The emerging role of Nrf2 in mitochondrial function. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;88:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q, Li C, Yu L. Gambogic acid inhibits spinal cord injury and inflammation through suppressing the p38 and Akt signaling pathways. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17:2026–2032. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.8026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funatsu H, Noma H, Mimura T, Eguchi S, Hori S. Association of vitreous inflammatory factors with diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gverovic Antunica A, Bucan K, Kastelan S, Kastelan H, Ivankovic M, Sikic M. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in the Dubrovnik-Neretva County. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2019;27:160–164. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a5213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishaq M, Khan MA, Sharma K, Sharma G, Dutta RK, Majumdar S. Gambogic acid induced oxidative stress dependent caspase activation regulates both apoptosis and autophagy by targeting various key molecules (NF-kappaB, Beclin-1, p62 and NBR1) in human bladder cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1840:3374–3384. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh K, Ye P, Matsumiya T, Tanji K, Ozaki T. Emerging functional cross-talk between the Keap1-Nrf2 system and mitochondria. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2015;56:91–97. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.14-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joussen AM, Murata T, Tsujikawa A, Kirchhof B, Bursell SE, Adamis AP. Leukocyte-mediated endothelial cell injury and death in the diabetic retina. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:147–152. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63952-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CY, Wang Q, Wang XM, Li GX, Shen S, Wei XL. Gambogic acid exhibits anti-metastatic activity on malignant melanoma mainly through inhibition of PI3K/Akt and ERK signaling pathways. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;864:172719. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.172719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Shan P, Li H. Gambogic acid prevents angiotensin II induced abdominal aortic aneurysm through inflammatory and oxidative stress dependent targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR and NFkappaB signaling pathways. Mol Med Rep. 2019;19:1396–1402. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.9720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Lu Q, Chen W, Li J, Li C, Zheng Z. Vitamin D3 protects against diabetic retinopathy by inhibiting high-glucose-induced activation of the ROS/TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. J Diabetes Res. 2018;2018:8193523–8193511. doi: 10.1155/2018/8193523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudian-Sani MR, Jami MS, Mahdavinezhad A, Amini R, Farnoosh G, Saidijam M. The effect of the microRNA-183 family on hair cell-specific markers of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Audiol Neurootol. 2018;23:208–215. doi: 10.1159/000493557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao K, Shu W, Qiu Q, Gu Q, Wu X. Salvianolic acid A protects retinal pigment epithelium from OX-LDL-induced inflammation in an age-related macular degeneration model. Discov Med. 2017;23:129–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell. 2002;10:417–426. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JW, Adamis AP, Shima DT, D’Amore PA, Moulton RS, O’Reilly MS, Folkman J, Dvorak HF, Brown LF, Berse B, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor is temporally and spatially correlated with ocular angiogenesis in a primate model. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:574–584. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palempalli UD, Gandhi U, Kalantari P, Ha V, Arner RJ, Narayan V, Ravindran A, Prabhu KS. Gambogic acid covalently modifies IkappaB kinase-beta subunit to mediate suppression of lipopolysaccharide-induced activation of NF-kappaB in macrophages. Biochem J. 2009;419:401–409. doi: 10.1042/bj20081482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J, Li L, Wang Y, Zhai J, Chen G, Hu K. Gambogic acid induces heme oxygenase-1 through Nrf2 signaling pathway and inhibits NF-kappaB and MAPK activation to reduce inflammation in LPS-activated RAW264.7 cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;109:555–562. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H, Zhang Z, Wang X, Li R, Hou W, Bi W, Zhang X. Inhibition of autophagy induces IL-1beta release from ARPE-19 cells via ROS mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation under high glucose stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;463:1071–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer MA, Kermany DS, Waters J, Jansen ME, Tyler L. Diabetic macular edema: it is more than just VEGF. F1000Res. 2016;5:1019. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.8265.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss O. The retinal pigment epithelium in visual function. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:845–881. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X, Liu C, Li T, Lin CJ, Hao ZY, Zhang H, Zhao G, Chen YY, Guo A, Hu CM. Gambogic acid alleviates inflammation and apoptosis and protects the blood-milk barrier in mastitis induced by LPS. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;86:106697. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Zhu X, Zhang K, Yao Y, Zhuang M, Tan CY, Zhou FF, Zhu L. Puerarin inhibits amyloid β-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation in retinal pigment epithelial cells via suppressing ROS-dependent oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stresses. Exp Cell Res. 2017;357:335–340. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen J, Wen JL, Pei HY, Wang XH, Xie CF, Li SC, Huang L, Qiu N, Wang WW, Cheng X, Chen LJ. Gambogic acid exhibits anti-psoriatic efficacy through inhibition of angiogenesis and inflammation. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;74:242–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Hu G, Lu Y, Zheng J, Chen J, Wang X, Zeng Y. Palmitic acid aggravates inflammation of pancreatic acinar cells by enhancing unfolded protein response induced CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein beta-CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein alpha activation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2016;79:181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2016.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Guo H, Sun H, Zhang W, Sun C, Wang J. UNC119 mediates gambogic acid-induced cell-cycle dysregulation through the Gsk3β/β-catenin pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2016;27:988–1000. doi: 10.1097/cad.0000000000000416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan PS, Tang S, Zhang HF, Guo YY, Zeng ZW, Wen Q. Nerve growth factor protects against palmitic acid-induced injury in retinal ganglion cells. Neural Regen Res. 2016;11:1851–1856. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.194758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Ding L, Liu WY, Feng F, Guo QL, You QD. Recent advances in chemistry and biology of gamboge. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2013;38:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, He S, Li S, Zhang R, Peng A, Chen L. In vitro and in vivo antiangiogenic activity of caged polyprenylated xanthones isolated from Garcinia hanburyi Hook. f. Molecules. 2013;18:15305–15313. doi: 10.3390/molecules181215305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau JW, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, Lamoureux EL, et al. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:556–564. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Chen F, Wang W, Wang H, Zhang X. Resolvin D1 inhibits inflammatory response in STZ-induced diabetic retinopathy rats: possible involvement of NLRP3 inflammasome and NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Mol Vis. 2017;23:242–250. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngblood H, Robinson R, Sharma A, Sharma S (2019) Proteomic biomarkers of retinal inflammation in diabetic retinopathy. Int J Mol Sci 20. 10.3390/ijms20194755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Youns M, ElKhoely A, Kamel R. The growth inhibitory effect of gambogic acid on pancreatic cancer cells. Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol. 2018;391:551–560. doi: 10.1007/s00210-018-1485-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Saaddine JB, Chou CF, Cotch MF, Cheng YJ, Geiss LS, Gregg EW, Albright AL, Klein BEK, Klein R. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in the United States, 2005-2008. JAMA. 2010;304:649–656. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]