Abstract

Introduction

Smoke-free school hours (SFSHs) entails a smoking ban during school hours and might be an effective intervention to reduce the high smoking prevalence in vocational schools. For SFSH to be effective, the policy must be adequately implemented and enforced; this challenge for schools constitutes a research gap. The ‘Smoke-Free Vocational Schools’ research and intervention project has been developed to facilitate schools’ implementation of SFSH. It is scheduled to run from 2018 to 2022, with SFSH being implemented in 11 Danish vocational schools. This study protocol describes the intervention project and evaluation design of the research and intervention project.

Methods and analysis

The intervention project aims to develop an evidence-based model for implementing SFSH in vocational schools and similar settings. The project is developed in a collaboration between research and practice. Two public health NGOs are responsible for delivering the intervention activities in schools, while the research partner evaluates what works, for whom, and under what circumstances. The intervention lasts one year per school, targeting different socioecological levels. During the first 6 months, activities are delivered to stimulate organisational readiness to implement SFSH. Then, SFSH is established, and during the next 6 months, activities are delivered to stimulate implementation of SFSH into routine practice. The epistemological foundation is realistic evaluation. The evaluation focuses on both implementation and outcomes. Process evaluation will determine the level of implementation and explore what hinders or enables SFSH becoming part of routine practice using qualitative and quantitative methods. Outcomes evaluation will quantitively assess the intervention’s effectiveness, with the primary outcome measure being changes in smoking during school hours.

Ethics and dissemination

Informed consent will be obtained from study participants according to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and Danish data protection law. The study adheres to Danish ethics procedures. Study findings will be disseminated at conferences and further published in open-access peer-reviewed journals.

Keywords: public health, health policy, qualitative research, protocols & guidelines

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study draws on realistic evaluation and aims to answer both research and practice needs by generating new application-oriented knowledge on how to implement smoke-free school hours in vocational schools and similar settings.

The study includes both implementation/process evaluation and outcomes evaluation in a unified multimethods study design.

The intervention has been developed in a joint venture between research and practice that emphasises including practice-based experience and research evidence, which may generate high external validity and more sustainable implementation practices.

It is a limitation to the internal validity, that the study seeks to assess outcomes without the use of control schools. However, the practice is considered appropriate in realistic evaluation.

The study seeks to integrate both qualitative and quantitative methods, which is a methodological challenge, as the methods represent different epistemological paradigms.

INTRODUCTION

From August 2021, a school tobacco policy (STP) of smoke-free school hours (SFSH) is expected to be ratified in all Danish educational institutions with at least one student aged under 18. The policy basically stipulates a smoking ban for students during school hours—both inside and outside school grounds. An expanded definition of SFSH also bans smoking by school staff, managers and visitors (smoke-free work hours). Additionally, SFSH might include all tobacco-related products (eg, cigarettes, vapers and snuff). SFSH is an expansion of traditional STPs, which do not prohibit smoking outside school grounds.1 The rationale is the same: restricting smoking behaviour as a means to prevent exposure to secondhand smoke, smoking initiation, and smoking continuation among adolescents and young adults.2 3 Restricting smoking behaviour can further be linked to political denormalisation strategies aiming to make the future smoke-free: a tobacco endgame.4 Evidence about SFSH is sparse, but some researchers5 suggest that it might be more effective than traditional STPs, which have been shown to relocate smoking to just outside school premises (eg, at the school entrance), and therefore do not remove smoking visibility.5 6 Additionally, traditional STPs can have adverse effects on students with lower socioeconomic status (SES), (lower odds of antismoking social beliefs),7 which suggest that SFSH might be a more appropriate strategy in schools with low SES groups, such as vocational schools.

In Denmark, vocational education and training (VET) is a short, practical upper-secondary education for a specific service or industry, such as hairdresser, carpenter, office assistant, or chef. It is characterised by a combination of traditional inschool education and out-of-school apprenticeship in the future workplace. Danish vocational students have low SES backgrounds8 and are over-represented in smoking behaviour: 29% smoke daily, compared with 9% in general upper-secondary education.9 10 The average vocational student age is 24 years, but as 14% of these students are aged 15–17 years,11 the SFSH law will apply to Danish vocational schools. As such, the law has considerable health-promoting potential: it may reduce smoking within a vulnerable population group setting (vocational schools) and contribute towards decreasing health inequality.12 However, policies which are not well implemented will not improve health.13–16 We conceptualise the implementation of SFSH as a school organisational process with the end-goal of incorporating the policy into routine practice.17 Staff and managers must enact and enforce the policy as part of their professional duties, and students must experience the policy as an accepted part of their everyday school life. Hence, enforcement is a significant task of organisational implementation.16 18–20 Despite legislation imposing STPs in many secondary schools across Europe, they are often poorly implemented and enforced.21–24

Three reviews have systematised decades of evidence related to STP implementation. The 2014 systematic review by Galanti et al 15 identified implementation components that improve STPs’ impact on student smoking behaviour (eg, strict and consistent enforcement). However, the authors also showed that most studies do not measure implementation fidelity and that enforcement is inconsistently operationalised across studies.15 Two realist reviews,5 16 as part of the SILNE-R project (2015–2018),25 yield prominent new insights into the functioning of STPs. The first shows how STPs’ implementation and comprehensiveness affects students’ beliefs and behaviour: for example, if smoking is not visible during school hours, students feel less pressure to conform to others’ smoking behaviour.5 The second shows that staff enforcement depends on whether they 1) Believe that STP enforcement is their role and duty, (2) Have confidence to deal with students’ negative responses when enforcing the rules, and (3) Experience enforcement having a positive impact on students.16 Other recent studies26–28 have explored which practices facilitate or hinder adopting SFSH; one key finding is that schools should develop a shared understanding about the policy being part of their jurisdiction prior to implementation.26–28 Seen together, the studies point towards important elements for schools to consider when implementing SFSH, but do not provide knowledge about what activities and processes can stimulate better implementation. In other words, most studies focus on understanding existing STPs rather than generating new knowledge about how to facilitate implementation. The latter might only be possible using interventionist study designs. One intervention study provides an important measure of STP implementation fidelity.29 To the best of our knowledge, however, no intervention studies have examined how to stimulate or measure the process of implementing SFSH into routine practice. As such, it remains unclear how to best support, stimulate and measure the implementation of SFSH.

To address the identified research gap, we developed the ‘Smoke-Free Vocational Schools’ intervention project, which aims to facilitate implementing SFSH in vocational schools and to generate new knowledge about the implementation and effectiveness of SFSH. The intervention takes place in 11 Danish vocational schools from 2018 to 2022.

Realistic evaluation

Realistic evaluation (RE) is the epistemological foundation of the evaluation. Pawson and Tilley developed the RE approach, arguing that to generate application-oriented knowledge for policy and practice, it is more useful to address ‘what works, for whom and under what circumstances’, rather than evaluating whether an intervention ‘works’.30 According to RE, interventions might generate different outcomes (O) in different contexts (C) by triggering underlying changes in reasoning and behaviour among participants—conceptualised as mechanisms (M).31 As such, interventions may ‘work’ by enabling participants to make different choices, but the choices are always constrained by a context, such as the organisational norms, values and discourses that operate in school settings. ‘Complex intervention’ is used to describe innovations within highly complex and emergent social systems,32 such as schools.33 34 It can be understood in relation to the RE notion of ‘open systems’, defined by Pawson and Tilley30 as ‘[T]he acknowledgement that programmes are implemented in a changing and permeable social world, and that programme effectiveness may thus be subverted or enhanced through the unanticipated intrusion of new contexts’ (p 218). Hence, the overall RE methodology is to examine C+M = O relations in complex interventions, known as CMO configurations.30

Study aim

In reporting complex interventions, the intervention and evaluation design must be clearly described to enable replication and synthesis of evidence,35 36 yet many RE studies inadequately report their methodological practices.37–39 Therefore, the aim of this study protocol is twofold: (1) To describe the Smoke-Free Vocational Schools intervention, and (2) To present how the intervention is evaluated, including the study design, specific methods and theoretical assumptions.

Methods and analysis

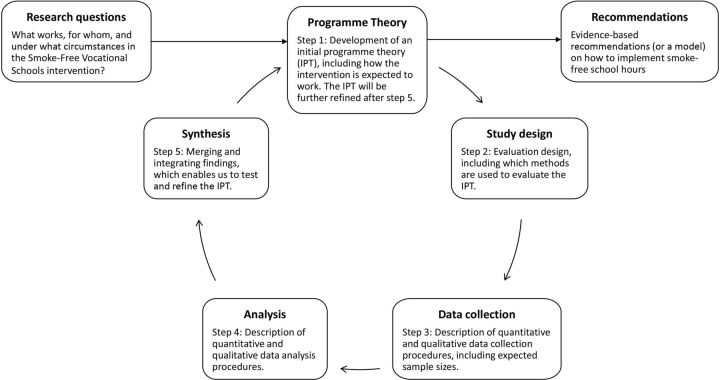

The overall objective of the Smoke-Free Vocational Schools intervention project is to develop an evidence-based model for implementing SFSH in Danish vocational schools and comparable settings. To accomplish the objective, the study examines what works, for whom and under what circumstances. RE starts with the development of an initial programme theory (IPT).39 Programme theory is theory incarnate, explicitly explaining which context mechanisms should be triggered among different actors to produce desired outcomes.40 41 In relation to the Smoke-Free Vocational Schools intervention, the IPT represents a hypothesis on how and why to implement SFSH and the study design is developed to test the hypothesis. We have structured this study protocol following the steps of the realist research cycle,39 42 as shown in figure 1. The content was further informed by the Standard Protocol Items for Randomised Trials statement.

Figure 1.

Realist research cycle of the Smoke-Free Vocational Schools intervention project.

Step 1: Programme theory

The intervention project is a collaboration between research and practice. Two Danish public health NGOs—the Danish Heart Foundation and the Danish Cancer Society—are practice partners, while Steno Diabetes Centre, Copenhagen is the research partner. The practice partners are responsible for delivering the intervention activities in schools; the research partner is responsible for conducting a formative evaluation of the implementation processes and outcomes. The research and practice partners together developed the IPT, and it is part of our method to continually discuss and apply preliminary research findings as part of the formative evaluation. As such, we follow the proposal of RE37 by iteratively testing and developing the programme theory in parallel to new empirical learnings.

The IPT was developed through a workshop where research and practice worked collaboratively. The practice partners contributed their extensive first-hand experience of implementing tobacco preventive efforts in different school contexts: for example, the Danish Cancer Society has tailored a motivational interviewing course to support smoking cessation by upper-secondary school students. The translation of practice-based experience and ideas into the intervention might increase the sustainability of implementation practices and improve external validity.43 The research partner contributed with evidence on effective tobacco preventive methods in vocational schools, based on recent research and the results from a qualitative study on facilitators and barriers for implementing SFSH.28 At the workshop, we developed a graphic representation of the intervention,44 including the short-term and long-term outputs, outcomes, and impact expected of different intervention activities targeting actors within and outside the school. The workshop process also served as a learning and management tool, as the research and practice partners developed a shared understanding on how the intervention is expected to produce change, which is crucial in public health interventions.45

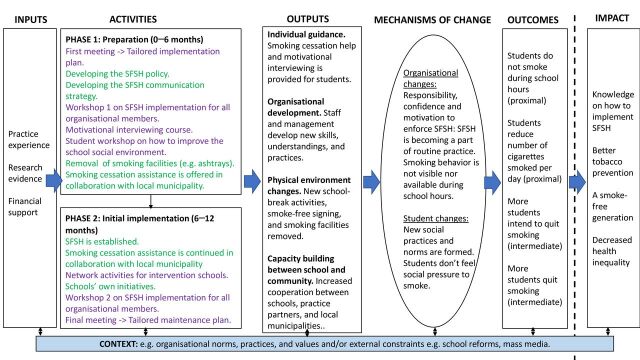

The Smoke-Free Vocational Schools intervention

The intervention is delivered in two phases, each lasting approximately 6 months (as shown in figure 2). During phase 1, activities are delivered to stimulate organisational readiness46 to implement SFSH: these include preparing staff and managers for their new professional tasks, and establishing new school-break facilities for students as alternatives to social smoking. At the beginning of phase 2, SFSH is established. During phase 2, activities are delivered to stimulate the gradual implementation of SFSH into routine practice by supporting schools in addressing emergent challenges, such as nicotine dependence or enforcement. Table 1 describes all the intervention activities.

Figure 2.

Graphic representation of the initial programme theory of the Smoke-Free Vocational Schools intervention. SFSH: Smoke-free school hours. The intervention activities delivered by practice partners are shown in purple. The activities or processes managed by schools but facilitated by practice partners are shown in green.

Table 1.

Description of intervention activities in the Smoke-Free Vocational Schools intervention

| Activity | Description | Purpose | Participants |

| Phase 1 | |||

| First meeting | An initial meeting between the schools and practice partners, where the SFSH implementation plan is discussed. | To ensure that the schools have a clear implementation plan and know how the intervention activities can support them. | Practice partners. |

| To clarify role distributions between different stakeholders. | School principal and other management representatives. | ||

| School project coordinator. | |||

| Local municipality representative. | |||

| Developing the SFSH policy | The schools develop their SFSH policy, including rules and responsibilities for sanctioning and enforcement. The practice partners provide inspirational material, for example, other schools’ policies. | To ensure the schools develop a clear SFSH policy, which aligns with the schools’ rules of conduct. | Decided locally in schools. |

| Practice partners recommend that schools establish a working group including both management and staff representatives. | |||

| Developing the SFSH communication strategy | The schools develop their internal and external SFSH communication strategy. The practice partners provide inspirational material and financial support to smoke-free signing. | To ensure that all organisational members (eg, students and staff) and relevant external stakeholders (eg, neighbours and apprenticeship workplaces) know what SFSH entails. | Decided locally in schools. |

| Workshop one on SFSH implementation | A joint meeting at the schools for all school staff and managers, facilitated by the practice partners. | To stimulate a joint vision and understanding of why the school is implementing SFSH. | Practice partners. |

| To ensure that all organisational members feel confident to enforce SFSH. | All school staff and managers. | ||

| To address school-specific challenges and issues, for example, resistance. | Local municipality representative. | ||

| Motivational interviewing course | A selected group of school staff and managers attend a 2-day course delivered by the practice partners. | To provide new knowledge and skills for the selected staff and managers, who are supposed to become key drivers of the implementation in school. | Practice partners. |

| To help nicotine-addicted students to cope with not smoking during school hours. | Selected school staff and managers including the school project coordinator. | ||

| Local municipality representative. | |||

| Smoking cessation assistance | Offered to students and staff in collaboration with the local municipality. | To help motivated staff and students quit smoking. | Students and staff. |

| The type of assistance varies between municipalities, depending on local resources and availabilities. | Local municipality representative. | ||

| Student workshop | A participatory student workshop on how to improve the social environment, delivered in schools by the practice partners. The schools are given financial support (averaging €15 000 per school) to establish some of the best school-break activities. | To create alternatives to smoking communities at school. | Practice partners. |

| To ensure that the new school-break activities are relevant for the students. | Selected group of students. | ||

| Local municipality representative. | |||

| The school management and school project coordinator approve the new school-break activities. | |||

| Removal of smoking facilities | The schools remove smoking facilities, for example, ashtrays. | To signal that the school is smoke-free. | Decided locally in schools. |

| Phase 2 | |||

| The school tobacco policy of SFSH | The SFSH policy is established in schools. The schools must enact and enforce the policy. | To prevent exposure to secondhand smoke. | Decided locally in schools. |

| To prevent smoking initiation and continuation. | Practice partners recommend that all school staff and managers play a role in enforcement. | ||

| Continued smoking cessation assistance | Smoking cessation assistance is offered to students and staff in collaboration with the local municipality. | To help motivated staff and students quit smoking. | Students and staff. |

| The type of smoking cessation assistance varies between municipalities, depending on local resources and availabilities. | Local municipality representative. | ||

| Network activities for intervention schools | A network for intervention schools is established by the practice partners. Two larger network activities for all schools are delivered during 2018–2020. | To facilitate schools exchanging experiences of implementing SFSH and learning from one another. | School principal and school project coordinator are invited. |

| Participation in network activities will be decided locally in schools. | |||

| Schools’ own initiatives | Supportive actions which ease the implementation of SFSH. | Decided locally by schools. | Decided locally by schools. |

| Workshop 2 | A joint meeting at the schools for all staff and managers, facilitated by the practice partners. | To address school-specific challenges in relation to implementing SFSH. | Practice partners. |

| All school staff and managers. | |||

| Local municipality representative. | |||

| Final meeting | A final meeting between the schools and practice partners to discuss the SFSH maintenance plan. | To ensure the schools have a clear maintenance plan and know how the municipality and practice partners can support them after the intervention period. | Practice partners. |

| School principal. | |||

| School project coordinator. | |||

| Local municipality representative. | |||

SFSH, smoke-free school hours.

The activities are expected to produce short-term outputs, which are operationalised in four sets according to ecological levels:47 (1) Individual guidance, for example, smoking cessation assistance for students (individual); (2) Organisational development, for example, development of professional skills and confidence to enforce SFSH (interpersonal); (3) Physical environment changes, for example, new school-break activities (structural/organisational); and (4) Capacity building between school and community, for example, increased cooperation between the school and the local municipality (community).

The activities and outputs are together expected to produce ‘mechanisms of change’, which are the underlying changes in reasoning and behaviour among participants, triggered by the intervention and the intervention context. We expect that the central context mechanisms allowing SFSH to become part of routine practice will be found at the organisational level, where school staff and managers take responsibility for SFSH, feel confident to enforce SFSH and feel motivated by positive student responses.16 At the student level, we expect context mechanisms to be triggered by: (1) Staff and managers enforcing SFSH, resulting in decreased smoking visibility and, in turn, students becoming less prone to conform to others’ smoking behaviour5; and (2) The new school-break activities resulting in new practices and social norms at school.48 As such, we expect SFSH to become a natural and accepted part of students’ everyday school life.

The mechanisms of change are expected to result in outcomes related to students’ smoking behaviour. Our primary outcome measure is ‘changes in smoking during school hours’, while the secondary outcome measure is ‘changes in the number of cigarettes smoked per day’; both are proximal outcomes. The intermediate outcome measures are ‘changes in intention to quit’ and ‘changes in smoking status’. The long-term impact of the intervention will not be evaluated as part of this study.

Step 2: Study design

The study is designed to test the IPT through focusing on both implementation/process evaluation and outcomes evaluation. As considered most appropriate in RE,30 37 we use a multimethods design, which allows us to quantify some elements of CMO configurations (eg, changes in smoking behaviour) and qualitatively explore the change mechanisms and context.49 The process evaluation investigates to what extent the intervention activities have been delivered and are implemented according to the programme theory, and seeks to explore the mechanisms that hinder or enable SFSH becoming part of routine practice. The outcomes evaluation assesses the intervention’s outcomes in terms of students’ smoking behaviour, using a one-group pretest–post-test study design, with subgroup analysis further determining for whom the intervention is most effective.

The intervention is delivered at 11 schools during 2018–2020, 7 of which are included in the evaluation. The remaining four are considered ‘pilot schools’, where the intervention activities and evaluation methods (eg, questionnaires) are tested and adjusted. The practice partners recruited schools that wanted to implement the expanded version of SFSH, banning all tobacco-related products (eg, cigarettes, vapers and snuff) during school and work hours for students, staff and visitors. The sample of seven vocational schools accounts for 10% of all Danish vocational schools; represents all four main educational areas (technical, business, agriculture and food services, and social and health services); and covers three (out of five) geographical regions. As such, the study sample includes a broad variety of vocational school contexts across the country and is, thus, considered representative of all Danish vocational schools.

Process evaluation

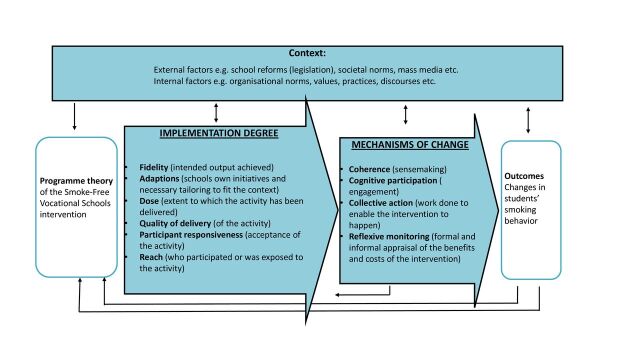

The process evaluation comprises two mutually informing parts based on the RE-compatible50 Medical Research Councils guidelines for Process Evaluation of Complex Interventions.35 Our operationalisation of the framework in the study is shown in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Process evaluation of the smoke-free vocational schools intervention, based on the medical research councils guidelines for process evaluation of complex interventions.

The ‘Implementation degree’ study quantitatively measures implementation levels for each of the four sets of outputs and for the SFSH policy based on fidelity, adaptions, dose, quality of delivery, participant responsiveness and reach. Hence, the study seeks to occupy a middle position in the fidelity versus adaptions debate50 with an emphasis on measuring both central intervention implementation (eg, extent of enforcement) and the schools’ contextual initiatives and tailoring (eg, means and methods of enforcement). The ‘Mechanisms of change’ study explores the implementation processes using both qualitative and quantitative methods. Normalisation process theory17 proposes that implementation processes are shaped and motivated by four generative mechanisms—coherence, cognitive participation, collective action and reflexive monitoring. This will be the guiding theory in the investigation of processes that hinder or enable SFSH becoming part of routine practice.

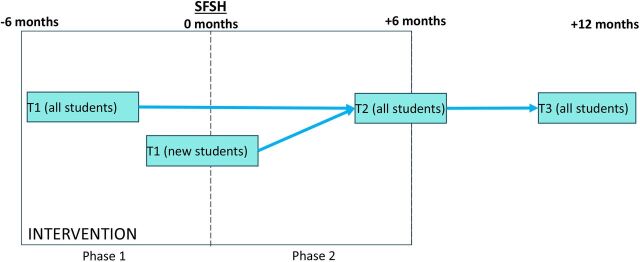

Outcomes evaluation

The outcomes evaluation assesses the effectiveness of the intervention in terms of the primary and secondary outcomes, measured before SFSH (Time 1, T1), 6 months after the establishment of SFSH (Time 2, T2) and 12 months after the establishment of SFSH (Time 3, T3), as shown in figure 4. The primary outcome measure is changes in (1) Smoking during school hours (dichotomous variable (yes/no)); the secondary outcome measures are changes in (2) (a) The number of cigarettes smoked per day (continuous variable), (b) Intention to quit (nominal variable) and (c) Smoking status (nominal variable). Further, to elaborate on CMO configurations, subgroup analyses are performed to investigate for whom the intervention is most effective and to explore relations between findings from the process evaluation, that is, the SFSH implementation fidelity measure and quantitative indicators of implementation processes. The study thus seeks to elaborate on outcomes across the programme and considers outcomes for different subgroups within the population without using control schools, which is considered appropriate for RE.37 51 52

Figure 4.

Timeline for the intervention (square box) and outcomes evaluation for the Smoke-Free Vocational Schools Intervention.

Step 3: Data collection

The evaluation lasts approximately 1.5 years per school and covers intervention phase 1 (6 months) and intervention phase 2 (6 months), with the final follow-up conducted 6 months after the intervention has ended. During this time period, qualitative and quantitative data will be collected from students, staff and managers to increase the validity of findings.53 Table 2 presents an overview of all data collection measures and procedures, including estimates of eligible participants and expected response rates. The different data collection measures provide cross-cutting insights for the process and outcomes evaluations. A preliminary operationalisation of how the data contribute to each is presented in online supplemental file 1.

Table 2.

Overview of data in the Smoke-Free Vocational Schools intervention project, including eligible participants (N), expected response rates (N) and data collection procedures

| Data collection | When | N (eligible) | N (expected) | Procedure |

| Student survey 1 | Before SFSH | 3000 | 2000 | Baseline measure focusing on smoking behaviour, etc. Electronic questionnaire distributed by the research team (in school). |

| Structured observations on school grounds | Before SFSH | NA | NA | Structured observations focusing on smoke-free signing, smoking facilities and smoking visibility (in school). |

| Staff survey 1 | Before SFSH | 1200 | 600 | Electronic questionnaire distributed to all staff and managers about SFSH preparation (email). |

| Project coordinator survey 1 | Before SFSH | 7 | 7 | In-depth electronic questionnaire concerning SFSH preparation (email). |

| Principal manager interview | Before SFSH | 7 | 7 | Semistructured interview focusing on SFSH preparation, including motivation and past experiences (in school or via Skype). |

| Student survey 2 | 6 months after SFSH | 3000 | 2000 | Follow-up one measure focusing on smoking behaviour, etc. Electronic questionnaire distributed by the research team (in school). |

| Structured observations on school grounds | 6 months after SFSH | NA | NA | Structured observations focusing on smoke-free signing, smoking facilities and smoking visibility (in school). |

| Staff survey 2 | 6 months after SFSH | 1200 | 600 | Electronic questionnaire distributed to all staff and managers about the gradual SFSH implementation (email). |

| Project coordinator survey 2 | 6 months after SFSH | 7 | 7 | In-depth electronic questionnaire about the gradual SFSH implementation (email). |

| Staff focus group | 6–8 months after SFSH | 21–42 | 21–42 | Focus groups with teaching staff, counsellors and/or others assigned a special role in relation to SFSH. Focusing on daily practice, reasoning and how/if the intervention has supported the gradual SFSH implementation (in school or via Skype). |

| Project coordinator interview | 6–8 months after SFSH | 7 | 7 | Semistructured interview focusing on daily practice, reasoning and how/if the intervention has supported the gradual SFSH implementation (in school or via Skype). |

| Student survey 3 | 12 months after SFSH | 3000 | 2000 | Follow-up to measure focusing on smoking behaviour, etc. Electronic questionnaire distributed by the research team (in school). |

| Structured observations on school grounds | 12 months after SFSH | NA | NA | Structured observations focusing on smoke-free signing, smoking facilities and smoking visibility (in school). |

| Staff survey 3 | 12 months after SFSH | 1200 | 600 | Electronic questionnaire distributed to all staff and managers about the gradual SFSH implementation (email). |

| Facilitator survey (NGOs) | Before and after SFSH | NA | NA | Electronic questionnaire distributed to the practice partners in relation to different intervention activities, that is, student and staff workshops and courses. |

SFSH, smoke-free school hours.

bmjopen-2020-042728supp001.pdf (71.5KB, pdf)

Student surveys

Electronic student surveys are conducted during school hours at three different time points. Students self-report smoking behaviour54 and intention to quit,55 smoking-related rules and practices and social norms at school,56–61 self-efficacy,62–64 well-being,65 66 educational information, and demographics. Validated questions have been used when possible and the questionnaire has been pilot-tested in two vocational school classes (n=30 participants) to ensure face validity.67 Due to the VET school structure, combining in-school education and apprenticeships, individual follow-up is rarely possible. Instead, both paired data from the same individuals and cross-sectional data will be collected. To maximise response rates, data collection is organised by the research partners in each school and conducted during school hours. The students are given time to complete the questionnaire and ask questions. The survey takes approximately 30 min per school class. Based on experience with the procedure,9 we expect that 95% of students will participate in the study.

Sample size calculation

The outcome measure used to determine sample size is change in the number of cigarettes smoked during school hours per day, per student, based on individual follow-up data. We assume that 30% are daily smokers who on average smoke 18 cigarettes per day, including 8 during school hours.68 We assume that the intervention will reduce smoking intensity during school hours by 50%, meaning a reduction of 4 cigarettes smoked per school day (with a SD of 4 and 3 and correlation=0.3). To avoid type I errors and type II errors, we respectively chose a 5% significance level and power at 80%. Assuming that the data are normally distributed, we will need to conduct individual follow-up on 11 daily smokers per school. We expect a 30% reduction in participants from baseline to follow-up. Accounting for this, the sample size must include 14.3 daily smokers per school. Thus, if the smoking prevalence is 30%, 24.4 students per school must participate in the prospective study. As seven schools are participating, the sample size for the prospective study must include (at least) 171 students.

Staff and project coordinator surveys

Staff and project coordinator surveys are electronically distributed to all school organisational members—that is, managers, teaching staff, counsellors, administrative and kitchen staff, and so on—at three different time points to follow the gradual implementation of SFSH. It is important to include all organisational members as all are expected to be affected by SFSH. The surveys include questions to investigate the implementation degree (eg, fidelity, dose) and the validated Normalization Measure Development (NoMAD) Scale69 70 to grasp the implementation processes. The project coordinator surveys include additional questions about the implementation work (eg, collaboration with the NGO partners, local municipality and contextual tailoring). The surveys have been pilot-tested among staff, managers and project coordinators at the four pilot schools (n=23 participants) to ensure face validity.67 Surveys distributed to NGO partners both before and after SFSH explore their role in facilitating meetings.

Structured observations

Structured observations on school grounds are carried out by the researchers at the same time points as the student surveys. Inspired by other studies,71 72 the structured observations will include observations on smoking visibility (eg, who, where and how many smokers are visible during school hours) and physical environment changes (eg, smoke-free signing and removal of smoking facilities). Data will be registered as field notes.

Interviews and focus groups with principal manager, project coordinator, and teachers

Semistructured individual interviews and focus groups with school principals, project coordinators, and teachers are carried out to explore the implementation processes in terms of intervention modalities, change mechanisms and context features.73 It is important to gather interview material from the different respondent groups as they provide different perspectives, challenges and opportunities in relation to implementing SFSH. Specifically, school principals have decision-making power on SFSH and knowledge about school strategic-political processes; project coordinators have in-depth knowledge and experience of all actions for implementing SFSH; and teachers have direct contact with students and are expected to play a large role in enforcing SFSH. During interviews the role of the NGO partners is also explored.

Step 4: Data analysis

Process evaluation

Implementation levels are assessed using confirmatory factor analysis.74 Inspired by Bast et al,29 data are used to develop indexes of low and high implementation degree, while associations between the outputs and the overall SFSH implementation fidelity model are analysed using regression analysis. This allows us to investigate to what extent the intervention activities predict the implementation degree of SFSH. Mechanisms of change are explored by combining qualitative and quantitative data and by using the generative mechanisms proposed by normalisation process theory (coherence, cognitive participation, collective action and reflexive monitoring) to structure the analysis. Qualitative data will be coded using an abductive approach, whereas quantitative data will be analysed using descriptive techniques to further explain, supplement, or challenge the qualitative analyses of what enables or hinders SFSH becoming part of routine practice.

Outcomes evaluation

The outcomes evaluation uses multilevel linear or logistic regression, depending on the outcome measures.75 The primary analysis will be a two-level model, with students (level 1) nested in schools (level 2). In secondary analysis, we will investigate effects according to predefined subgroups, such as sex, age and SES. To further elaborate on CMO configurations, we will test the associations between quantitative measures of implementation degree and implementation processes from the process evaluation, using descriptive analysis, logistic regression and/or factor analysis.76 77

Step 5: Synthesis

Empirical and theoretical knowledge about the implementation and outcomes of the intervention will be synthesised into recommendations on how to implement SFSH. RE advocates using retroduction and abduction in iterative processes to test and refine IPT.37 73 78 Retroduction is a form of inference that seeks to identify and verify the mechanisms theorised to have generated the phenomena under study,73 78 whereas abduction is the process of describing empirical data using theoretical concepts,73 with emphasis on analysing data that fall outside an initial theoretical frame or premise.78 79 Regarding the Smoke-Free Vocational Schools intervention project, our goal is to integrate qualitative and quantitative findings from the process and outcomes evaluations to reanalyse the IPT in terms of what works, for whom and under what circumstances, using a retroductive-abductive approach. Based on the refined programme theory, we will be able to develop model recommendations for implementing SFSH in vocational schools and similar settings.

Ethics and dissemination

In public health interventions it is important to examine and clarify possible negative reverse effects, so as to avoid further interventions generating the same negative effects.80 Therefore, unexpected consequences of the intervention will be explored and reported to minimise and avoid participants feeling stigmatised in this study and similar future studies.

The study has been reported to the Capital Region of Denmark’s legal centre for personal data handling (journal number: VD-2018–485). Informed consent will be obtained from all study participants according to the General Data Protection Regulation and Danish data protection law. The study adheres to the ethics procedures in Denmark. Study findings will be disseminated at international and national conferences and further published in open-access peer-reviewed journals. Also, the study findings will be used by the practice partners in their further work supporting schools implementing SFSH, as well as by other stakeholders (eg, schools).

Patient and public involvement

This study protocol describes a health promotion intervention and no patients have been involved. Public involvement, defined as collaboration with public health partners with knowledge on the VET school setting, has been extensive. The partnering NGO organisations and research institution have worked closely together and collaborated and agreed on the design of the intervention and evaluation. The NGO partners have been involved in the development of the research questions and on choosing the outcome measures and are coauthoring this study protocol. The NGO partners recruited the VET schools and supported the schools in the implementation of SFSH. The evaluation results will be disseminated to NGO partners, VET schools and students through SoMe news and a short two-page publication in layman language.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participating vocational schools who readily shared their time and experiences with the research team.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conceived and designed the study: AVH, TBC, MS, KHR and CDK; Refined the study design and obtained ethical approval: AVH, CP, TT-T, CDK; Wrote and revised this manuscript (fully or in part): AVH, TBC, MS, KHR, CP, TT-T, CDK.

Funding: This work was supported by The Danish Health Authority grant number: 1-1010-308/56.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1. Boyce JC, Mueller NB, Hogan-Watts M, et al. Evaluating the strength of school tobacco policies: the development of a practical rating system. J Sch Health 2009;79:495–504. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00439.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Agaku IT, Obadan EM, Odukoya OO, et al. Tobacco-free schools as a core component of youth tobacco prevention programs: a secondary analysis of data from 43 countries. Eur J Public Health 2015;25:210–5. 10.1093/eurpub/cku203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aveyard P, Markham WA, Cheng KK. A methodological and substantive review of the evidence that schools cause pupils to smoke. Soc Sci Med 2004;58:2253–65. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sæbø G, Scheffels J. Assessing notions of denormalization and renormalization of smoking in light of e-cigarette regulation. Int J Drug Policy 2017;49:58–64. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schreuders M, Nuyts PAW, van den Putte B, et al. Understanding the impact of school tobacco policies on adolescent smoking behaviour: a realist review. Soc Sci Med 2017;183:19–27. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Leatherdale ST, Brown KS, Cameron R, et al. Social modeling in the school environment, student characteristics, and smoking susceptibility: a multi-level analysis. J Adolesc Health 2005;37:330–6. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schreuders M, Kuipers MA, Mlinarić M, et al. The association between smoke-free school policies and adolescents’ anti-smoking beliefs: moderation by family smoking norms. Drug Alcohol Depend 2019;204:107521. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Erhvervsudannelser i Danmark 2019 . [Vocational education and training in Denmark 2019], 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Klinker CD, Aaby A, Ringgaard LW, et al. Health literacy is associated with health behaviors in students from vocational education and training schools: a Danish population-based survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:671. 10.3390/ijerph17020671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pisinger V, et al. UNG19 - Sundhed og trivsel på gymnasiale uddannelser 2019 [The health and wellbeing survey in Danish generel upper secondary education], 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Uddannelsesstatitisk . Educational statistics Denmark. Available: https://uddannelsesstatistik.dk/Pages/Reports/1838.aspx

- 12. Frohlich KL, Potvin L. Transcending the known in public health practice: the inequality paradox: the population approach and vulnerable populations. Am J Public Health 2008;98:216–21. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol 2008;41:327–50. 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Murray E, Treweek S, Pope C, et al. Normalisation process theory: a framework for developing, evaluating and implementing complex interventions. BMC Med 2010;8:63. 10.1186/1741-7015-8-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Galanti MR, Coppo A, Jonsson E, et al. Anti-tobacco policy in schools: upcoming preventive strategy or prevention myth? A review of 31 studies. Tob Control 2014;23:295–301. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Linnansaari A, Schreuders M, Kunst AE, et al. Understanding school staff members’ enforcement of school tobacco policies to achieve tobacco-free school: a realist review. Syst Rev 2019;8:177. 10.1186/s13643-019-1086-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. May C, Finch T. Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: an outline of normalization process theory. Sociology 2009;43:535–54. 10.1177/0038038509103208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lipperman-Kreda S, Paschall MJ, Grube JW. Perceived enforcement of school tobacco policy and adolescents' cigarette smoking. Prev Med 2009;48:562–6. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Adams ML, Jason LA, Pokorny S, et al. The relationship between school policies and youth tobacco use. J Sch Health 2009;79:17–23. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00369.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moore L, Roberts C, Tudor-Smith C. School smoking policies and smoking prevalence among adolescents: multilevel analysis of cross-sectional data from Wales. Tob Control 2001;10:117–23. 10.1136/tc.10.2.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jarlstrup NS, Juel K, Pisinger CH, et al. International approaches to tobacco use cessation programs and policy in adolescents and young adults: Denmark. Curr Addict Rep 2018;5:42–53. 10.1007/s40429-018-0187-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gordon J, Turner KM. Ifs, maybes and butts: factors influencing staff enforcement of pupil smoking restrictions. Health Educ Res 2003;18:329–40. 10.1093/her/cyf021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Turner KM, Gordon J. Butt in, butt out: pupils’ views on the extent to which staff could and should enforce smoking restrictions. Health Educ Res 2004;19:40–50. 10.1093/her/cyg005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schreuders M, Linnansaari A, Lindfors P, et al. Why staff at European schools abstain from enforcing smoke-free policies on persistent violators. Health Promot. Int 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. SILNE-R . Enhancing the effectiveness of programs and strategies to prevent smoking by adolescents: a realist evaluation comparing seven European countries. Available: http://silne-r.ensp.network/about-silne/objectives/

- 26. Schreuders M, van den Putte B, et al. , SILNE-R consortium . Why secondary schools do not implement Far-Reaching smoke-free policies: exploring deep core, policy core, and secondary beliefs of school staff in the Netherlands. Int J Behav Med 2019;26:608–18. 10.1007/s12529-019-09818-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Heinze C, Hjort AV, Elsborg P, et al. Smoke-free-school-hours at vocational education and training schools in Denmark: attitudes among managers and teaching staff - a national cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2019;19:813. 10.1186/s12889-019-7188-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rasmussen KH, Hansen AV, Klinker CD. Udbredelse AF røgfri skoletid på erhvervsskoler: en forundersøgelse TIL en effektiv tobaksforebyggelsesindsats på erhvervsskoler. Hjerteforeningen: Steno Diabetes Center, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bast LS, Due P, Bendtsen P, et al. High impact of implementation on school-based smoking prevention: the X:IT study—a cluster-randomized smoking prevention trial. Implement Sci 2015;11. 10.1186/s13012-016-0490-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation. Sage, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dalkin SM, Greenhalgh J, Jones D, et al. What’s in a mechanism? Development of a key concept in realist evaluation. Implement Sci 2015;10:49. 10.1186/s13012-015-0237-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moore GF, Evans RE, Hawkins J, et al. From complex social interventions to interventions in complex social systems: future directions and unresolved questions for intervention development and evaluation. Evaluation 2019;25:23–45. 10.1177/1356389018803219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Theorising interventions as events in systems. Am J Community Psychol 2009;43:267–76. 10.1007/s10464-009-9229-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Keshavarz N, Nutbeam D, Rowling L, et al. Schools as social complex adaptive systems: a new way to understand the challenges of introducing the health promoting schools concept. Soc Sci Med 2010;70:1467–74. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: medical research council guidance. BMJ 2015;350:h1258. 10.1136/bmj.h1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655. 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wong G, Westhorp G, Greenhalgh J, et al. Quality and reporting standards, resources, training materials and information for realist evaluation: the RAMESES II project. Health Serv Deliv Res 2017;5:1–108. 10.3310/hsdr05280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gilmore B, McAuliffe E, Power J, et al. Data analysis and synthesis within a realist evaluation: toward more transparent methodological approaches. Int J Qual Methods 2019;18:160940691985975. 10.1177/1609406919859754 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Marchal B, van Belle S, van Olmen J, et al. Is realist evaluation keeping its promise? A review of published empirical studies in the field of health systems research. Evaluation 2012;18:192–212. 10.1177/1356389012442444 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sharpe G. A review of program theory and theory-based evaluations. Am Int J Contemp Res 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pawson R, Sridharan S. Chapter 4: Theory-driven evaluation of public health programmes. : Evidence-Based public health: effectiveness and efficiency. Oxford University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Marchal B, Giralt AN, Sulaberidze L, et al. Designing and evaluating provider results-based financing for tuberculosis care in Georgia: a realist evaluation protocol. BMJ Open 2019;9:e030257. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Evans R, Scourfield J, Murphy S. Pragmatic, formative process evaluations of complex interventions and why we need more of them. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69:925–6. 10.1136/jech-2014-204806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kellogg Founation . Using logic models to bring together planning, evaluation, and action. Logic Model Development Guide 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rod MH, Ingholt L, Bang Sørensen B, et al. The spirit of the intervention: reflections on social effectiveness in public health intervention research. Crit Public Health 2014;24:296–307. 10.1080/09581596.2013.841313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Weiner BJ. A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implement Sci 2009;4:67. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, et al. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q 1988;15:351–77. 10.1177/109019818801500401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ingholt L, Sørensen BB, Andersen S, et al. How can we strengthen students’ social relations in order to reduce school dropout? An intervention development study within four Danish vocational schools. BMC Public Health 2015;15. 10.1186/s12889-015-1831-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rogers PJ. Using programme theory to evaluate complicated and complex aspects of interventions. Evaluation 2008;14:29–48. 10.1177/1356389007084674 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Moore G. Process evaluation of complex interventions. UK medical Research Council (MRC) guidance. full texst. Available: https://mrc.ukri.org/documents/pdf/mrc-phsrn-process-evaluation-guidance-final/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51. Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, et al. RAMESES publication standards: realist syntheses. BMC Med 2013;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hawkins AJ. Realist evaluation and randomised controlled trials for testing program theory in complex social systems. Evaluation 2016;22:270–85. 10.1177/1356389016652744 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Suter W. Introduction to educational research: a critical thinking approach. SAGE Publications, Inc, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kremers SPJ, Mudde AN, de Vries H. Development and longitudinal test of an instrument to measure behavioral stages of smoking initiation. Subst Use Misuse 2004;39:225–52. 10.1081/JA-120028489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot 1997;12:38–48. 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chung A, Rimal RN. Social norms: a review. Rev. Commun. Res 2016;4:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Eisenberg ME, Forster JL. Adolescent smoking behavior: measures of social norms. Am J Prev Med 2003;25:122–8. 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00116-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lozano PA. Smoking-related stigma: a public health tool or a damaging force ? (Doctoral dissertation), 2016. Available: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59. Dohnke B, Weiss-Gerlach E, Spies CD. Social influences on the motivation to quit smoking: main and moderating effects of social norms. Addict Behav 2011;36:286–93. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. East K. The development of tools to measure norms towards smoking, nicotine use and the tobacco industry, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Brown-Johnson CG, Cataldo JK, Orozco N, et al. Validity and reliability of the internalized stigma of smoking inventory: an exploration of shame, isolation, and discrimination in smokers with mental health diagnoses. Am J Addict 2015;24:410–8. 10.1111/ajad.12215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Conner M, Sandberg T, McMillan B, et al. Role of anticipated regret, intentions and intention stability in adolescent smoking initiation. Br J Health Psychol 2006;11:85–101. 10.1348/135910705X40997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Romppel M, Herrmann-Lingen C, Wachter R. A short form of the general self-efficacy scale (GSE-6): development, psychometric properties and validity in an intercultural non-clinical sample and a sample of patients at risk for heart failure. GMS Psycho Soc Med 2013. 10.3205/psm000091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sterling KL, Ford KH, Park H, et al. Scales of smoking-related self-efficacy, beliefs, and intention: assessing measurement invariance among intermittent and daily high school smokers. Am J Health Promot 2014;28:310–5. 10.4278/ajhp.121009-QUAN-490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Knoop HH, Universitet A, Holstein BE. Elevernes fællesskab og trivsel i skolen. Analyser af Den Nationale Trivselsmåling [Pupils communities and well-being in primary school. Analysis based on the national well-being survey], 2017. https://dcum.dk/media/2107/dcum-rapport-elevernes-trivsellow.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tennant R, Hiller L, Fishwick R, et al. The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2007;5:63. 10.1186/1477-7525-5-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Thomas SD, Hathaway DK, Arheart KL. Face validity. West J Nurs Res 1992;14:109–12. 10.1177/019394599201400111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ringgaard LW, Heinze C. UNG19 - Sundhed og trivsel på erhvervsuddannelser 2019 [The Health and Wellbeing survey in Danish vocational education and training], 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Rapley T, Girling M, Mair FS, et al. Improving the normalization of complex interventions: part 1 - development of the NoMAD instrument for assessing implementation work based on normalization process theory (NPT). BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18. 10.1186/s12874-018-0590-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Finch TL, Girling M, May CR, et al. Improving the normalization of complex interventions: part 2 - validation of the NoMAD instrument for assessing implementation work based on normalization process theory (NPT). BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18. 10.1186/s12874-018-0591-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Rozema AD, Mathijssen JJP, van Oers HAM, et al. Evaluation of the process of implementing an outdoor school ground smoking ban at secondary schools. J Sch Health 2018;88:859–67. 10.1111/josh.12692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Saluja K, Rawal T, Bassi S, et al. School environment assessment tools to address behavioural risk factors of non-communicable diseases: a scoping review. Prev Med Rep 2018;10:1–8. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.01.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Mukumbang FC, Marchal B, Van Belle S, et al. Using the realist interview approach to maintain theoretical awareness in realist studies. Qual. Res 2019;146879411988198. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Floyd FJ, Widaman KF. Factor analysis in the development and refinement of clinical assessment instruments. Psychol Assess 1995;7:286–99. 10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.286 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kirkwood BR, Sterne JAC, Kirkwood BR. Essential medical statistics. Blackwell Science, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ford JA, Jones A, Wong G, et al. Access to primary care for socio-economically disadvantaged older people in rural areas: exploring realist theory using structural equation modelling in a linked dataset. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18. 10.1186/s12874-018-0514-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ravn R. Testing mechanisms in large-N realistic evaluations. Evaluation 2019;25:171–88. 10.1177/1356389019829164 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Jagosh J. Retroductive theorizing in Pawson and Tilley’s applied scientific realism. J Crit Realism 2020;19:121–30. 10.1080/14767430.2020.1723301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Meyer SB, Lunnay B. The application of abductive and retroductive inference for the design and analysis of Theory-Driven sociological research. Sociol Res Online 2013;18:86–96. 10.5153/sro.2819 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Bonell C, Jamal F, Melendez-Torres GJ, et al. ‘Dark logic’: theorising the harmful consequences of public health interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69:95–8. 10.1136/jech-2014-204671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-042728supp001.pdf (71.5KB, pdf)