Abstract

Objectives

The time taken for older people to recover from hip fracture can be extensive. The aim of this study was to gain an understanding of patient and informal carer experience of recovery in the early stage, while in acute care.

Design

A phenomenological (lived experience) approach was used to guide the design of the study. Interviews and observation took place between March 2016 and December 2016 in acute care.

Setting

Trauma wards in a National Health Service Foundation Trust in the South West of England.

Participants

A purposive sample of 25 patients were interviewed and observation taking 52 hours was undertaken with 13 patients and 12 staff. 11 patients had memory loss, 2 patients chose to take part in an interview and observation. The age range was 63–91 years (median 83), 10 were men. A purposive sample of 25 informal carers were also interviewed, the age range was 42–95 years (mean 64), 11 were men.

Results

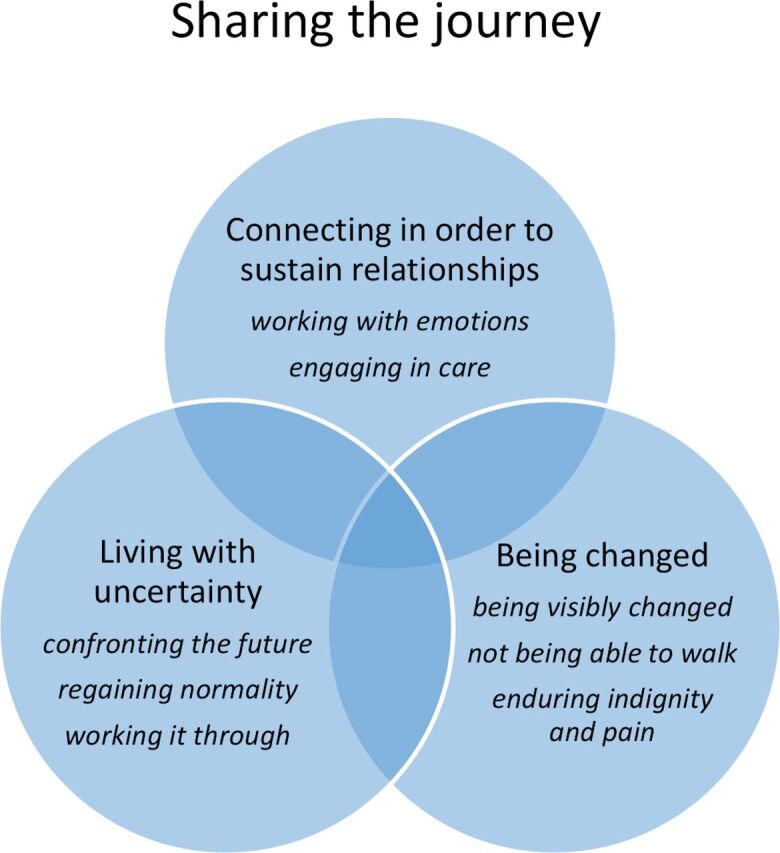

The results identified how participants moved forward together after injury by sharing the journey. This was conveyed through three themes: (1) sustaining relationships while experiencing strong emotions and actively helping, (2) becoming aware of uncertainty about the future and working through possible outcomes, (3) being changed, visibly looking different, not being able to walk, and enduring indignity and pain.

Conclusion

This study identified the experience of patients and informal carers as they shared the journey during a challenging life transition. Strategies that support well-being and enable successful negotiation of the emotional and practical challenges of acute care may help with longer term recovery. Research should focus on developing interventions that promote well-being during this transition to help provide the foundation for patients and carers to live fulfilled lives.

Keywords: orthopaedic & trauma surgery, hip, quality in healthcare

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The use of interviews and observation has provided rich data and clear insights into patient’s and informal carer’s experience of sharing the journey of recovery from a hip fracture during acute care.

Involving patients with memory loss through observation ensured their experience was included within the analysis.

Inclusionary consent, where the researcher was alert to the patient’s comfort with their presence, was important during observation.

The themes developed from this exploratory study require further review in diverse samples to assess the transferability.

Inclusion of healthcare staff in the sample would situate the shared journey of recovery within the context of care.

Introduction

This study explores the experience of patients who have had a hip fracture and their informal carers, a term used to describe supportive and caring relationships with family and friends. This could be a partner, their daughter or son, relative or a friend. In the 2011 Census, 5.8 million people provided unpaid care to family or friends.1 In England, Wales and Northern Ireland, the National Hip Fracture Database identified 66 313 people aged 60 years or older who experienced a hip fracture in 2018, with a mortality rate of 6.1% up to 30 days after injury.2 Estimates of 12% mortality at 4 months and 20% at 1 year have been made for those over 80 years of age. Treatment for hip fracture is normally surgery, either fixation or arthroplasty3; and UK healthcare costs have been estimated to be £2 billion.4 In addition, there is a significant reduction in ability to walk and health-related quality of life at 1 year compared with preinjury.3 Increased support for independent living, or a change in living arrangements is evident. In 2018 in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 31% of patients did not return to their original residence.2

Evidence from patient experience of hip fracture indicates that recovery is arduous and support from informal carers is required. Patients can feel frailer and emotionally vulnerable.5 6 To gain control, they balance their need for help with a determination to be independent, despite potential risks to their safety.7 In their own home, they can feel outside the ‘umbrella of care’ and unsupported.8 Patients make adaptions to their lives in the context of anxiety, feeling burdened and uncertain about the future.9 In hospital patients experience pain, indignity and can feel dehydrated. They dislike being dependent on staff but often feel unready for discharge.8 Patients identify relationships with staff as crucial. They want staff to know them, validate their needs and involve them in their care.10 11 Informal carers of people with hip fractures find caring for others rewarding but stressful. The core concept ‘engaging in care: struggling through’ identifies how informal carers learnt from experience, negotiated the unknown and changed their lives to encompass caring while aiming to keep themselves healthy.12

There is growing evidence of the prolonged burden of recovery from hip fracture and generic evidence of the quality of care for older patients in acute care. However, there is limited evidence specifically related to the experience of hip fracture from patient and carer perspectives during early recovery while in acute care. Therefore, this study aims to provide direction for support and rehabilitation by exploring the research questions: (1) what are older people’s experiences of hip fracture, including those with memory loss? and (2) what are informal carers’ experiences of being alongside them while they are in acute care?

Methods

The methodology drew on phenomenology13 in order to understand the participant’s lived experience as used previously in orthopaedic trauma.14–16 Phenomenology enabled experience to be explored within participant’s social and cultural contexts in order to illicit what was important to them. Meaning inherent in the participant’s experience was drawn out through a process of interpretation. Interpretation involved reading, listening and reflecting on elements that were of concern to participants while being aware of the researchers’ own positionality, for example role and experience. A full discussion of the methods for this study is provided in the protocol.17 The methods used were interviews and participant observation.

Ethics

All participants with capacity provided informed written consent, received a participant information sheet and had at least 24 hours to consider their participation. For patients with memory loss, a personal consultee, a family member or friend provided written informed advice that in their opinion the patient would not object to taking part. Inclusionary consent,18 where the researcher is constantly alert to cues indicating the patient’s degree of comfort with their presence, underpinned the methods. In addition, clinical staff caring for the patient provided written informed consent to take part in the observation and identified the patient’s mood, activities and when the observation could safely take place. However, due to the high level of acuity of other patients and pace of work during the study period, staff involvement was limited.

Participants

A purposive sample of 36 patients with a hip fracture took part. There were 25 patient interviews and 13 patients took part in 52 hours of participant observation (two patients chose interviews and observation). Eleven of the 13 patients did not have capacity to consent and personal consultees were obtained. The patient sample aimed to obtain a range of sex, age and include those without capacity. The carer sample aimed to obtain a range of sex, age and a range of relationships with the patients. Details of the sample are supplied in table 1, information about participants. The patient age range was 63–91 years (median 83), 10 were men and interviews were 15–55 min long (average 28). Time since admission was 4–19 days (median 9 days). Twelve staff members consented to be present during the observation. Interviews with 25 informal carers took place, the age range was 42–95 years, (median 62), 11 were men. Of these 5 were partners and 20 were daughters/sons, younger family members or a friend. There were 12 dyads where both patient and their carer were interviewed. The interviews took 20–55 min (average 26). Three patients were invited to take part but declined to take part due to tiredness, which alongside the shortness of some interviews indicates the frailty of this group.

Table 1.

Information about participants

| Characteristics | Number of participants |

| Patients | |

| Sex | |

| Male | 10 |

| Female | 26 |

| Age (years) median 83, range 63–91 | |

| Time since admission for hip fracture (days) Median 9, range 4–19 | |

| Participation in interviews | 25 |

| Participation in observation | 13 |

| Consented | 25 |

| Personal consultee due to lack of capacity | 11 |

| Participation in interview and observation | 2 |

| Invited but declined to participate | 3 |

| Patient and carer dyads | 12 |

| Carers | |

| Sex | |

| Male | 11 |

| Female | 14 |

| Age (years) median 62, range 42–95 | |

| Relationship to patient | |

| Husband | 4 |

| Wife | 1 |

| Daughter | 9 |

| Son | 6 |

| Other relative | 4 |

| Friend | 1 |

| Participation in interviews | 25 |

| Staff | |

| Consent to be involved in observation | 12 |

Participant observation

Participant observation, up to 4 hours at a time and informal chats about their experience were obtained by sitting with patients. Interactions were conversational, following patients’ interests, with prompts such as, ‘what is it like using this walking frame?’ Field notes were written as soon as possible after the interaction.

Interviews

Interviews took place on the ward, in a meeting room or ward area. The interviews were conversational in style, often including aspects of daily life to enable participants to feel comfortable and be able to tell the researcher what was important to them. For patients, the interviews led with the question, ‘tell me about what it is like to have a hip fracture?’ Informal carers were asked, ‘tell me what it is like caring for your relative/friend with a hip fracture?’ Prompts were used to enable participants to expand on aspects of their experience such as ‘What did that feel like?’, ‘What did you think?’ and ‘Tell me more about that.’

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI) was through the Oxford-led UK Musculoskeletal Trauma Group who at the time met regularly with clinical and research staff to discuss research studies. This group was involved in shaping the research question and design of the study, and identified the importance of including patients with memory loss. Two PPI partners were involved in two discussions during analysis to reflect on the evolving structure. Four PPI partners read the findings, could relate to them and felt that many aspects of their own experience were reflected in the paper. Additional individual perspectives included feeling alone in their own emotional bubble, not realising others have similar feelings.

Analysis

Interviews were digitally audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Analysis was undertaken by drawing together sentences with underlying meaning into codes. For example, both patients and informal carers described seeing a physical change in the patients: ‘I am full of holes’ and ‘she looks and feels very unglamorous’. These codes were gathered together under the category ‘being visibly changed’. This was combined with two other categories: ‘being unable to walk’ and ‘enduring indignity and pain’ to create the theme ‘being changed’. The themes convey the overall experience, drawing together the codes and categories into a central thread or ‘structures of experience’19 (p79). Carer and patient data contributed to all the themes but carer data led the theme (1) connecting in order to sustain relationships and patient data led the theme (2) being changed. The analysis was led by ET with LS-C, who undertook data collection, with regular discussion with the team to reflect on interpretation of the data. Both researchers were experienced female healthcare researchers with PhDs and prior experience of patients with traumatic injury (ET) and psychology (LS-C) and had no contact with the participants prior to the study. Management of data was facilitated by the use of NVivo 11, a qualitative software package. Rigour was demonstrated through trustworthiness.20 Key elements of trustworthiness were that the researchers were immersed in the data, provided a clear audit trail of the research process and supported the thematic framework with quotes to illustrate the themes. The sample and context have been described to enable transferability of the data. To maintain anonymity, participants were allocated a number: letter P for patient and C for informal carer. A copy of their transcript was offered to participants but they declined. Observations were written by the researcher in the form of field notes and included quotes from the patients.

Findings

Sharing the journey

The experience of having a hip fracture was a point of transition, where sharing the journey identified the emotional and physical work undertaken by patients and informal carers as they strove to remain connected and move forward at a time of change. The dynamic shift in relationships and interdependency was demonstrated though three themes: (1) ‘connecting in order to sustain relationships’, with categories of working with emotions and engaging in care; (2) ‘living with uncertainty’, with categories of confronting the future, regaining normality and working it through; and (3) ‘being changed’ with categories of being visibly changed, not being able to walk, and enduring indignity and pain. Figure 1 presents the themes and categories for sharing the journey.

Figure 1.

Presentation of the themes and categories for sharing the journey.

Theme 1: connecting in order to sustain relationships

Connecting in order to sustain relationships identified how being together changed, which required working with emotions and engaging in care. Working with emotions demonstrated how feelings were expressed or contained in order to sustain relationships. Engaging in care highlighted the intense activity undertaken by carers through presence, orientating and supporting their family member.

Working with emotions

The participants demonstrated a closeness to each other where lives intertwined and mutual support was provided. Many couples lived together, one couple for 55 years. Injury disrupted everyday life and there was a loss of companionship. Carers tried to keep busy but could feel out of control, lonely, bored or depressed: ‘now it is all haywire I can’t explain why but it’s haywire’ (C15). For carers, witnessing physical and emotional deterioration required suppression of emotions or distancing strategies. Delirium, memory loss, behavioural change and the possibility of death were particularly hard for carers who felt distressed and powerless to help. Carer’s own emotions often fluctuated depending on the patient’s state.

I mean she has deteriorated in a few days so rapidly from the person she was on Monday. It is quite scary really. It is horrible to see and know how much she is suffering and so yes I was finding it very hard and was very worried. She is a bit brighter in herself today and yesterday even though she still feels terrible, so I’m feeling a bit better. (C13)

Whilst visiting, energy was required to achieve calmness and to prevent expression of fear and frustration. Strategies that helped were timing of visits, short breaks away from the bedside or a reduction in visiting time. Containing emotions in light of rapid, visual deterioration was hard to maintain.

I’ve drawn up here (in the car) and thought I’m not sure I can face it and it is the babbling I don’t like, it scares me and how ill she looks. (C4)

Carers worked hard to contain their feelings to protect patients but struggled to find an emotional balance.

Engaging in care

In order to sustain a connection, carers actively engaged in care using three strategies: presence, orientating and supporting. Although challenging, regular long periods of physical presence were important to sustain relationships, understand clinical progress and the patient’s experience. Orientating occurred through visual and conversational cues to direct patients away from confused thoughts back to day-to-day reality. Carers acted as a conduit to staff, provided simple explanations to patients and also informed staff about the patient.

I think she is reliant on me to be this kind of filter between her and what is going on. I think she does rely on me to tell her what’s what although she’ll dismiss it…she’s not really able to take part in much conversation…I don’t think she’s able to. (C19)

Supporting was an active process of undertaking practical activities often built on existing knowledge of the person such as mental stimulation, nutrition and hydration. For carers, containing their own feelings combined with engaging in care was hard work, exhausting and sometimes felt like a battle if care needs were not met as expected.

Theme 2: living with uncertainty

Living with uncertainty conveyed how participants learnt to live with frailty and death as part of life by (1) confronting the future, (2) regaining normality and (3) working it through. Confronting the future identified their readiness to actively work through thoughts and feelings about recovery and death. Regaining normality demonstrated the struggle to move and undertake daily activities while being unsure of what was possible. Working it through showed how carers process the impact of injury through the experience of everyday life.

Confronting the future

Confronting the future was problematic for both patients and carers. Frank conversations between patients and their carers could be constrained if either was not ready to think about the future or mental ability was limited.

He tells me ‘I don’t know what’s going to happen in the future and I don’t really want to talk about it’. No he (the patient) doesn’t want to talk about it because he thinks it’s the end of the road (death). (C22)

The need to maintain autonomy and a meaningful life was evident alongside a growing realisation that life may be different from prior to injury.

‘I would hate not to be independent but it would make sense after this. I am 90’. She said to me that she likes to make her own decisions and ‘I like to be independent’, ‘I like to be in charge of my life’. (P34, observation)

For carers, uncertainty about the future underpinned a determination to push for recovery. Carers were fearful that patients would not progress without more physiotherapy and massive encouragement.

I shouted at him rather, I didn’t shout nastily but I tried to coax him to put his trust in them, he seems nervous which is understandable I suppose really, isn’t it, but I can…I say to come on you must do it, you won’t get home. (C15)

Getting a balance between rest and activity for patients was important, and they struggled with confidence and having the energy to maintain activities throughout the day.

Regaining normality

Getting back to normal was the ideal outcome for patients and carers but the extent to which this was possible was uncertain.

We were hoping to get her a little bit more mobile but I think with this broken hip now, that’s probably a forlorn hope. (C14)

The process of recovery was a new experience, largely unknown and patients were anxious about how they were going to get better.

What’s it like, a bloody nightmare. I’m generally pretty active, I don’t sit down for long and I’m known for always doing something … I don’t even know how long it will take, nobody’s actually told me that yet either. (P29)

Patients felt they had limited control over what they could do but also felt they needed to change their thoughts, feelings and actions. For example, acquire resilience, fortitude and a ‘lorry load of patience’ (P24). There was sadness at their loss of activities and hope that they could get back to how they were before.

Well to be fully mobile again and go back, well not maybe 100% of my old ways but being able to fend for myself because I’m quite happy living on my own. (P29)

The degree of recovery was unknown but there was acceptance that to move forward they needed help and had to come to terms with a slower more careful way of life.

Working it through

Working it through was an experiential process in which carers learnt to manage the impact of injury on daily life. Time and energy were required to work out what was best. Carers felt responsible for the quality of life their family member might have but struggled with the uncertainty of recovery. Some carers negotiated the death of their family member and appreciated staff support. Responsibility existed alongside a realisation there were no easy solutions and the consequences of caring could be life changing.

You just get on with it don’t you, I can’t abandon her I’ve got to do it so yes it’s frustrating and it’s tiring at times as well but I just do it. (C2)

Carers felt that the patients deserved ‘a chance’ of recovery (C21) and should have proactive rehabilitation. Many carers had already or were making adaptions to their lives to accommodate caring and needed to balance care with juggling multiple competing demands on their time, often leaving them tired, unable to sleep and worried about their own health.

Theme 3: being changed

Being changed conveyed a loss of self as patients lived with a body that looks and feels different, endured limited mobility, indignity and pain, and negotiated interdependence with others. This was identified through (1) being visibly changed, (2) not being able to walk, and (3) enduring indignity and pain.

Being visibly changed

Patients described their body as visually changed by age and further damaged by injury and treatment.

I am full of holes. (P12, observation)

Injury had changed what they could do and they had no choice but to work with their body and accept the changes.

I have abused my body by breaking my hip but we just get on and we’re all working together, my brain and my hip and my body, we’re all working together to get back together again. (P1)

Some patients experienced increasing frailty and felt that hip fracture was inevitable due to their decline in well-being, confidence, health and physical robustness. There was a struggle to come to terms with ageing.

I think somebody should have drummed it into my stupid head that it was a real risk and yet I knew it was a real risk and I did nothing about it. (P12)

Patients were concerned that their ability to maintain their appearance, hair, nails, makeup and clothes as they would normally had been disrupted by injury.

I looked in the mirror just now and I thought my god what a mess. My hair is all messed up. (P4)

It might fall off, my tooth…I feel like a witch. (P27, observation)

Being visibly changed by injury and unable to keep up normal daily activities added to a sense of being old and a loss of self. Patients and carers found this emotionally hard to process but worked hard to improve the patient’s appearance.

Not being able to walk

The loss of the ability to walk due to injury and subsequent pain had a devastating impact on patients and what they felt they could do when home.

Very unpleasant and very painful, very frustrating. Any words like that to describe it because I’m an active person, I have been all my life with the wife, because your life is cut off near enough. It’s soul destroying I find it when you’ve just got to lay here and you can’t do anything at all except to say the physio gives me exercises, yes I’ll do them I want to get back to normal again. At the moment I can’t stand on my feet so I’m not quite sure how long it’s going to be. (P2)

Activities that are normally taken for granted required conscious, deliberate thought followed by action. They felt they had to be stoic (‘don’t complain get on with it’ (P9), ‘obey certain rules and regulations’ (P5)), concentrate, be careful, find their balance and slowly re-learn how to manage their body in order to regain any spontaneity or freedom of movement. Not being able to walk or move as fluidly as they did before led to greater dependency on others. It also impacted on other areas of their body and pre-existing mobility problems. Learning to move and normal ‘taken for granted activities’ involved great concentration and determination but was also tiring and frustrating.

Enduring indignity and pain

Enduring or putting up with indignity and pain was a normal part of hospital life but caused a high degree of distress: ‘it is insulting, it is frustrating’ (P27, observation). No one was comfortable with the public nature of toileting. Frustration and anxiety were also exacerbated by existing chronic conditions.

Well it makes you into a baby because you can’t do anything for yourself. You become disabled I suppose, you need help to go to the toilet, you can’t even sit up without help and you have to wear a nappy which does annoy me. (P3)

Accessing timely care was difficult due to the busyness of the environment and patients managed by watching for the appropriate staff to ask for help, waiting for help to come and accepting any help offered, ‘I have to wait’ (P32, observation) and ‘then if your bed is wet, they said why have you done it?’ (P35, observation).

Loss of control over their ability to meet their own needs could be exacerbated by little things such as understanding, when several people talk at the same time ‘she was afraid and did not understand’ (P32, observation). Getting the balance right between enabling patients to maintain autonomy and ensuring they were cared for was a challenge for carers. Patients had a stoic approach to enduring the indignity of hospital life, did the best they could, listened to advice and hoped in the future.

Just keep your mouth shut, eat the grub and do as you’re told. (P29)

Enduring pain was considered an everyday event and at times pain could be overwhelming. Several had managed pain from chronic conditions for a long time. Being believed and staff acting on reports of pain, learning to live with pain and medication all helped. Lack of staff input, their own experience and knowledge about injury and anxiety about pain could hamper their ability to feel in control of pain. Occasionally, poor care was noted ‘you wouldn’t let a dog or an animal be in pain like that would you’ (C25). Patients with memory loss appeared to be enduring pain particularly on movement. This was often expressed in different ways and needed careful management to avoid indignity.

She cooperated but she had a bit of pain. She expressed it with her face or sounds. When the assistant washed her legs she complained more: ‘It always this leg’; ‘it is sore’. She looked and touched her bruises on her leg and hip. (P31, observation)

Enduring indignity and pain was therefore part of everyday life for patients and they managed by being stoic, being watchful and waiting for support.

Discussion

This qualitative study adds to recent research8 9 11 12 and identifies how patients and their informal carers shared the journey of hip fracture, through connecting in order to sustain relationships, living with uncertainty and being changed. We specifically focused on acute care and included patients with memory loss. The suddenness of injury precipitated a confrontation with ageing, frailty, uncertainty, dependency and death. A point of biographical disruption21 and transition with elements of vulnerability and endurance as previously identified in recovery from injury.14 22 Our findings indicate that hip fracture is a time of significant change where further support for mental and physical well-being may be required.

There were some limitations to our study. The sample was limited to the population on the wards and was not ethnically diverse. Further observations of people with memory loss and interviews with multidisciplinary staff could add to the understanding of the culture of care. However, the sample was purposive and people with memory loss were included. Data saturation where no new themes occur was achieved and PPI work suggests there is resonance with the findings.

Despite these limitations, this study highlights that patients and informal carers may benefit from supportive activities in acute care that: (1) sustain opportunities for companionship, (2) enable the processing of emotions as a consequence of injury, and (3) facilitate caring interactions in relation to pain and intimate bodily care. To enhance support through this challenging transition, understanding gained from participants could be used within strategies such as person-centred care, education and communication. Involvement of patients and their family underpins person-centred care,23 although this aspect can be inconsistent and families may struggle to acquire it.10 24 Opportunities for human connection through being included, being useful and being part of decisions are evident in partnership working.25 Education and support may facilitate the identification of, expression and processing of strong emotions allowing families to develop skills to live with change and uncertainty. Helping carers to develop an awareness of the burden of caring26 27 and the importance of self-compassion28 29 may help prevent compassion fatigue. Relationships with multidisciplinary staff, patient and family that are open and responsive to knowledge exchange, valuing carer expertise,10 30 may help to identify what matters to them. Caring interactions, good bodily care and assessment of pain, which is often underestimated by professionals,31 may support older people to self-manage their changed bodies. Being aware that organisational care can compound feelings of insignificance and powerlessness,10 32 be misaligned with patients’ needs,32 may help to challenge feelings of inevitability and decline.33 Negotiating a balance between individual autonomy and dependency on others for help, when injured, is challenging; and for informal carers, this continues after discharge.12 However, enabling patients to feel comfortable and in control,34 having appreciative caring conversations,35 valuing their identity, building relationships and involvement10 may support their negotiation of this challenging life transition.

Conclusion

This study identified the experience of patients and informal carers in sharing the journey of hip fracture, a challenging life transition epitomised by uncertainty and change. Strategies that support well-being and enable successful negotiation of the emotional and practical challenges of acute care may help with longer term recovery. Research should focus on developing interventions that promote well-being during this transition to help provide the foundation for patients and carers to live fulfilled lives.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the patients and informal carers who generously gave their time and energy to support this study. In addition, we would like to thank the PPI partners and all the staff who facilitated aspects of this study, particularly Chris Bouse.

Footnotes

Twitter: @oxford Trauma and Emergency Care@oxford_trauma

Contributors: ET and LS-C drafted this paper. The design and analysis were led by ET with LS-C who undertook the data collection. DL, JW and KW supported the project, were involved in the design, discussion of the findings and the development of this paper. RG was involved in the discussion of the findings and the development of this paper. KW provided funding for the study.

Funding: This work was supported by the Trauma Research, Kadoorie Centre for Critical Care Research and Education, and the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: All participants received an information sheet at least 24 hours prior to an event. Written informed consent or a personal consultee agreement was obtained.

Ethics approval: The project was given ethical approval by National Research Ethics Committee London—Riverside and Camberwell and St Giles in August 2015 REF: 15/LO/1205.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: We do not have consent for data sharing from the study participants.

References

- 1. White C. 2011 census analysis: unpaid care in England and Wales, 2011 and comparing with 2001: office for national Staistics, 2013. Available: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160109213406/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171766_300039.pdf

- 2. RCP . National hip fracture database annual report. London: RCP, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Griffin XL, Parsons N, Achten J, et al. Recovery of health-related quality of life in a United Kingdom hip fracture population. The Warwick Hip Trauma Evaluation--a prospective cohort study. Bone Joint J 2015;97-B:372–82. 10.1302/0301-620X.97B3.35738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Svedbom A, Hernlund E, Ivergård M, et al. Osteoporosis in the European Union: a compendium of country-specific reports. Arch Osteoporos 2013;8:137. 10.1007/s11657-013-0137-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zidén L, Scherman MH, Wenestam C-G. The break remains – elderly people's experiences of a hip fracture 1 year after discharge. Disabil Rehabil 2010;32:103–13. 10.3109/09638280903009263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bruun-Olsen V, Bergland A, Heiberg KE. "I struggle to count my blessings": recovery after hip fracture from the patients' perspective. BMC Geriatr 2018;18:18. 10.1186/s12877-018-0716-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McMillan L, Booth J, Currie K, et al. A grounded theory of taking control after fall-induced hip fracture. Disabil Rehabil 2012;34:2234–41. 10.3109/09638288.2012.681006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brett J. Exploring the lived experience of having a hip fracture: identifying patients'perspectives on thier health care needs. Coventry: University of Warwick, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rasmussen B, Uhrenfeldt L. Establishing well-being after hip fracture: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. Disabil Rehabil 2016;38:2515–29. 10.3109/09638288.2016.1138552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bridges J, Collins P, Flatley M, et al. Older people's experiences in acute care settings: systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Nurs Stud 2020;102:103469. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nicholson C, Morrow EM, Hicks A, et al. Supportive care for older people with frailty in hospital: an integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud 2017;66:60–71. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Saletti-Cuesta L, Tutton E, Langstaff D, et al. Understanding informal carers' experiences of caring for older people with a hip fracture: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Disabil Rehabil 2018;40:740–50. 10.1080/09638288.2016.1262467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heidegger M. Being and time. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Keene DJ, Mistry D, Nam J, et al. The ankle injury management (AIM) trial: a pragmatic, multicentre, equivalence randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation comparing close contact casting with open surgical reduction and internal fixation in the treatment of unstable ankle fractures in patients aged over 60 years. Health Technol Assess 2016;20:1–158. 10.3310/hta20750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tutton E, Achten J, Lamb SE, et al. A qualitative study of patient experience of an open fracture of the lower limb during acute care. Bone Joint J 2018;100-B:522–6. 10.1302/0301-620X.100B4.BJJ-2017-0891.R1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Phelps EE, Tutton E, Griffin X, et al. Facilitating trial recruitment: a qualitative study of patient and staff experiences of an orthopaedic trauma trial. Trials 2019;20:492. 10.1186/s13063-019-3597-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Saletti-Cuesta L, Tutton E, Langstaff D, et al. Understanding patient and relative/carer experience of hip fracture in acute care: a qualitative study protocol. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs 2017;25:36–41. 10.1016/j.ijotn.2016.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dewing J. Process consent and research with older persons living with dementia Research Ethics Review 2008;4:59–64. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Van Manen M. Researching lived experience, human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lincoln YS, Guba EG, Pilotta JJ. Naturalistic inquiry. 9. Newbury Park, California: Sage Publications Inc, 1985: 438–9. 10.1016/0147-1767(85)90062-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bury M. Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociol Health Illn 1982;4:167–82. 10.1111/1467-9566.ep11339939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tutton EA, Lamb J, Willett SE, et al. On behalf of the UK WOLLF research collaborators a qualitative study of the experience of an open fracture of the lower limb in acute care. The Bone and Joint Journal 2018;100-B:522–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kelley R, Godfrey M, Young J. The impacts of family involvement on General Hospital care experiences for people living with dementia: an ethnographic study. Int J Nurs Stud 2019;96:72–81. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Petry H, Ernst J, Steinbrüchel-Boesch C, et al. The acute care experience of older persons with cognitive impairment and their families: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud 2019;96:44–52. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wolf A, Moore L, Lydahl D, et al. The realities of partnership in person-centred care: a qualitative interview study with patients and professionals. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016491. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Parry JA, Langford JR, Koval KJ. Caregivers of hip fracture patients: the forgotten victims? Injury 2019;50:2259–62. 10.1016/j.injury.2019.09.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Longo UG, Matarese M, Arcangeli V, et al. Family caregiver strain and challenges when caring for orthopedic patients: a systematic review. J Clin Med 2020;9. 10.3390/jcm9051497. [Epub ahead of print: 16 05 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Andrews H, Tierney S, Seers K. Needing permission: the experience of self-care and self-compassion in nursing: a constructivist grounded theory study. Int J Nurs Stud 2020;101:103436. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McPherson S, Hiskey S, Alderson Z. Distress in working on dementia wards - A threat to compassionate care: A grounded theory study. Int J Nurs Stud 2016;53:95–104. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McPherson KM, Kayes NK, Moloczij N, et al. Improving the interface between informal carers and formal health and social services: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud 2014;51:418–29. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Seers T, Derry S, Seers K, et al. Professionals underestimate patients' pain: a comprehensive review. Pain 2018;159:811–8. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Featherstone K, Northcott A, Bridges J. Routines of resistance: an ethnography of the care of people living with dementia in acute hospital wards and its consequences. Int J Nurs Stud 2019;96:53–60. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Samra R, Griffiths A, Cox T, et al. Medical students' and doctors' attitudes towards older patients and their care in hospital settings: a conceptualisation. Age Ageing 2015;44:776–83. 10.1093/ageing/afv082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Baillie L. Patient dignity in an acute hospital setting: a case study. Int J Nurs Stud 2009;46:23–37. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dewar B, Nolan M. Caring about caring: developing a model to implement compassionate relationship centred care in an older people care setting. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50:1247–58. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.