Introduction

Caring for someone at home requiring palliative care is an ominous task. Unless the current support systems are better utilised and improved to meet the needs of those carers, the demand for acute hospital admissions will increase as the Australian population ages. The aim of this review was to examine the needs of unpaid carers who were caring for adults receiving palliative care in their home in Australia.

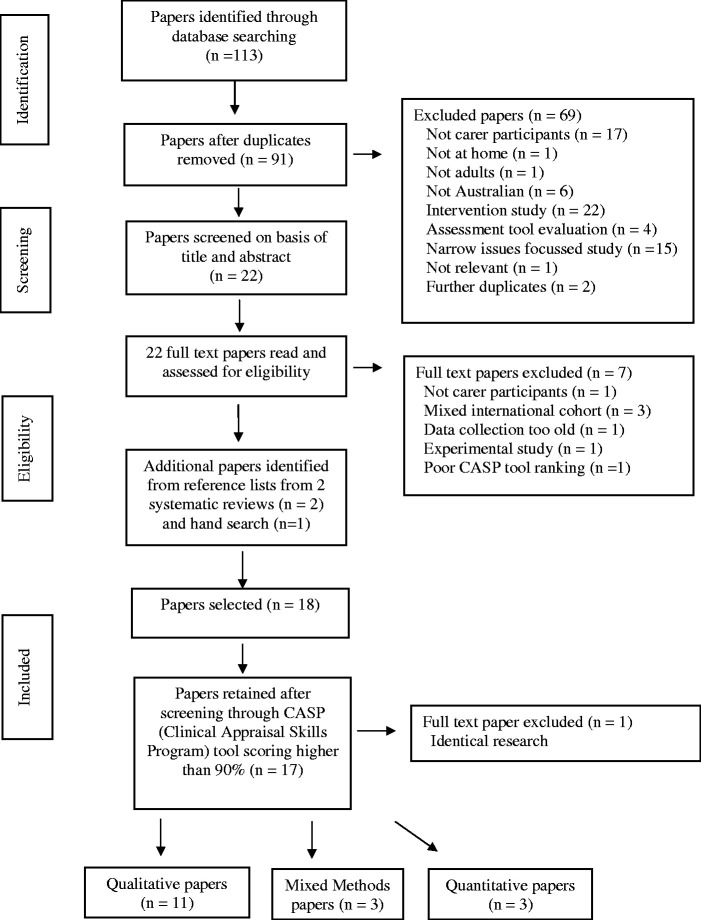

Methods: A systematic review of the literature was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Guidelines between 2008–2020.

Results: Only Australian papers were selected due to the intent to understand carers’ needs in the Australian context and 17 papers made up the final data set. Four themes emerged: 1) Perceived factors influencing caregiving; 2) Perceived impact and responses to caregiving; 3) Communication and information needs; and 4) Perceptions of current palliative support services and barriers to uptake.

Conclusion: Carers reported satisfaction and positive outcomes and also expressed feeling unprepared, unrecognised, stressed and exhausted.

Keywords: end of life, death/dying, barriers, services

Introduction

Caring for someone at home requiring palliative or end of life care is an ominous task. The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (2015), has standardised and defined the concept of ‘end of life care’ to mean care that is provided within the last 12 months of life, whilst ‘palliative care’ can be implemented for years for those with an incurable illness. This definition aligns with the World Health Organization (2018) definition of palliative care, which is ‘an approach that improves the quality of life of patients (adults and children) and their families who are facing problems associated with life-threatening illness. Palliative care prevents and relieves suffering through the early identification, correct assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, whether physical, psychosocial and spiritual’. In line with this purpose, organisational palliative support services can provide 24-hour multifaceted assistance to the patient, carer and family through referrals to multi-disciplinary practitioners.

All Australians benefit from a universal health insurance scheme (Medicare) which fully or partially subsidises healthcare service costs (Department of Health, 2020) and each state funds its own public hospitals and attached outpatient services (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2016b). Due to Australia’s large and varied geographical conditions, the population of 26 million people (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020) largely lives along the eastern seaboard. Australia’s First Nations people live in urban, rural or isolated remote communities. Since colonisation, Australia’s First Nations people have suffered a crisis in health due to long term physical and psychosocial neglect and poor government policy and resources (National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation, (2020). Over the last 50 years independent, Community-Controlled Health Services have been established allowing Australia’s First Nations people to begin to regain control of their health (National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation, 2020), yet there is a long way to go to close the gap between the health of First Nation and non-indigenous Australians (Commonwealth of Australia, 2020). The need to close the health care gap is also prevalent in the delivery of palliative care services and supporting Australia’s First Nation carers in the home.

It is challenging to adequately fund palliative support services with the rising trends in ageing in Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2013) and one solution may be to increase the amount of services provided in people’s homes where costs are lower (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2016a; National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling, 2004). For example, in 2014/2015 an average of 130 days of specialist community palliative care was provided for 16,084 people at home costing $2,574 per person compared to an average cost of $8,893 per person for 12 days of specialist palliative care inpatient services (Palliative Care Victoria, 2017). It is unclear what support systems and information sources carers are utilising as they provide palliative care at home. Therefore, a clearer understanding is needed in order to identify their needs to avoid unnecessary admissions to inpatient facilities resulting in further burden on the healthcare system in Australia. Therefore, the aim of this systematic literature review was to examine the needs of carers who were caring for adults receiving palliative care in their home in Australia.

Methods

This systematic review of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods Australian studies was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Liberati et al., 2009). A preliminary search was undertaken to test the results of various keyword combinations and to find a gap in the literature for the study that was to follow. The formal search was then undertaken using the combined keywords, MeSH terms and limiters including; ‘Palliative care OR end of life care OR terminal care OR dying AND Carers OR caregivers OR family members OR relatives OR informal carers AND home NOT nursing homes OR care homes OR long term care OR residential care AND NOT children OR adolescents OR youth OR child OR teenager’, as it was intended to capture a wide sweep of papers on the topic of palliative care. As the intent was not to compare Australian with international literature, but understand the carers’ needs in an Australian context, a further limiter namely, ‘AND Australia OR Australian’ was added. Restrictor dates were set from 2008 in order to examine the current literature and to accommodate the latest nursing practice and service user funding models. Only peer reviewed journals and English language papers were searched through via MEDLINE, CINAHL Complete, E-Journals, PsycINFO, Caresearch and Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition databases. A full summary of the final 17 examined papers is set out in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Included Australian Papers.

| Authors, year, region | Research aims | Participants, disease & sampling | Design & analysis | Limitations | CASP score | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aoun et al. (2010)Metropolitan & rural S.A. | To understand the profiles, service use, unmet needs & experiences of bereaved carers who are looking after a palliating patient with a NDD (neuro-degenerative disease) by applying a whole of population approach | 230 bereaved carersNDD, including motor neurone & multiple sclerosisStratified random sampling method | Quantitative survey Data from cross-sectional whole population study (S.A. Health Omnibus Survey) collected during face to face interviewsBivariate analysis complemented with regression analysis | Remote SA areas were not included in this population study. Carers’ views subject to change depending on their current emotional state.Possible recall bias due to 5 years since death of the patient prior to interview. | 100% | • Dying from a NDD takes a longer time which allows a larger network of friends & supports to be built up• Patients of NDD were more likely to die in the community than other palliating patients• Carers of NDD patients were more likely to be able to move on with their lives |

| Burns et al. (2011) Metropolitan S.A. | To examine the role and demographics of friends as carers for people with a terminal illness | 265 bereaved carer friendsMixed life limiting illnessesSampling method not identified | Quantitative-Data from cross-sectional whole population study (S.A. Health Omnibus Survey) Face to face interviewers recorded the statistical data which was analysed by a binary logistic regression model | Data from remote S.A. carers is not included, nor those of CaLD backgrounds. Respondent’s answers to some demographic Qs were in real time, not for the time of caring. | 90% | • As family structures change through frailty, estrangement or distance, younger friends may fulfil the role of end-of-life carer more often• Friends as carers provided substantially better care, utilised specialist palliative services more often and increased the chance of the patient dying at home |

| Dembinsky (2014) Rural W.A. | To examine the lived experiences of Yamatji women with breast cancer who live in Yamatji country, W.A. | 28 current respondents (of which 3 were non-Aboriginal health professionals).The 25 Aboriginal respondents comprised of 10 patients, 4 kin carers, 6 kin non-carers and 5 health professionals Breast cancerSampling method not identified | Qualitative – “Research topic yarning” style informal interviews with the patients and carers, formal interviews with medical personnel & participant observations Combined grounded theory & ethnographic immersionThematic analysis using Nvivo9 software | Small & all female sample size. Participant familiarity with each other due to snowballing may result in similar & communally acceptable responses. | 100% | • The Yamatji women view palliative care as end-of-life care and breast cancer as a death sentence.• The Yamatji women want to die ‘in country’• Logistical, cultural and geographical barriers made it difficult for the Yamatji women to access the hospital-based palliative care services |

| Essue et al. (2015) Metropolitan Melbourne, Vic. | To prospectively measure out-of pocket expenses for medical and health related care, economic hardship and the sources of financial stress for terminal cancer patients, and to examine patient’s and carer’s perspectives on these issues | 52 participants(30 patients and22 carers)CancerSampling method not identified | Mixed methods –Prospective case studyQuantitative data was collected from a 2-week financial diary plusMonthly in-depth semi-structured interviews - the 1st being face-to-face followed by monthly telephone interviews for up to 6 monthsQualitative data was content thematically analysed and coded with NVivo 8 software | Small sample size for quantitative study. All participants had private health insurance and were sourced from one palliative care service in an urban area. The findings will differ in marginalised or lower socio-economic areas or those with other life limiting diseases. | 100% | • The households who suffered the most economic hardship were likely to comprise a male patient who had to cease work early due to illness • Out of pocket expenses could overwhelm personal finances • Some carers did not have the time or energy to the complete the complex forms for social security• The safety net system was inflexible for the changing needs of the patients/carers and many struggled to pay for bills long before it kicked in. |

| Hatcher et al. (2014) Rural Vic. | To understand carers’ perspectives about the patient’s transition from community to hospital based palliative care | 6 current carers at time of 1st interview then 5 bereaved by time of 2nd interviewCancerConvenience sampling | Qualitative –Semi-structured interviews (at time of admission and 3 months later) Data was analysed thematically using NVivo 9 software | Small sample size. Recruitment by self-selection. | 90% | • Carers requested the patient be transferred to hospital due to acopia• Excellent communication between the palliative care team in the community and hospital services enabled a smoother transition into hospital for both patients and carers |

| Heidenreich et al. (2014) Metropolitan Sydney, N.S.W. | To explore the impact Chinese cultural norms has on immigrant Chinese women who are caring for a terminally ill person in Sydney and to explore access issues to palliative care support services | 5 current carers of Chinese ancestryUnidentified terminal illnessesPurposive sampling | Qualitative –Semi-structured face-to-face interviews using an exploratory and descriptive frameworkData analysed thematically using Braun & Clarke’s (2006) framework | Small sample size Participants taken from one site. | 90% | • Carers believed it was much easier to care for a palliating relative in the homeland than in Australia• Cultural norms restricted access to palliative and wider support services and prevented open discussion with the patient |

| Keesing et al. (2011) Metropolitan & rural W.A. | To examine how the role of caring impacts the usual routines of carers and whether community services provide support for these | 14 bereaved family carers A variety of life limiting diseasesPurposive sampling | Qualitative –Exploratory approach using grounded theory. Semi-structured face-to-face interviews. Data analysed by constant comparative method. | 13/14 participants were female. Small sample size but data saturation was reached. Difficult to obtain participants from rural areas. | 90% | • Loss of routine activities often caused carers to feel disengaged and deprived • Poor communication between health professionals and the carer created frustration, helplessness and disempowerment• Current services and carer community supports were inadequate |

| Kenny et al. (2010) Metropolitan Sydney, N.S.W. | To investigate the health-related quality of life of carers | 178 current carersMixed life limiting illnessesSampling method not identified | Quantitative –Cross-sectional observational study using the SF-36 Health Survey administered in a face to face interview. Multiple regression Analysis. | Low recruitment rate for a quantitative study. The mental health of the carer could impact on the findings. A longitudinal study may provide more conclusive results as caregiving demands change over time. | 90% | • Findings showed carers had better physical health but worse mental health than the general population• 35% of carers reported worse health than 12 months prior relating to the carer’s needs not caring time• Carers with poor health needed extra help with the patient’s medications, night assistance and emotional support |

| Lee et al. (2009) Regional, Vic. | To explore the experiences and palliative care needs of people with mesothelioma and asbestos-related lung cancer, their carers and service providers in the Latrobe Valley, Victoria | 13 participants (5 local legal & healthcare providers; 2 patients, 6 family carers)Mesothelioma & asbestos-related lung cancerConvenience sampling | Qualitative –Embedded descriptive case study design. In-depth interviews, media, local authority and employer reports and historical data. Data analysed by a constant comparative method | Small sample size due to lack of access to participants able to partake in the study, so unable to generalise findings. | 100% | • Medical diagnosis and/or services were delayed by part-time, inexperienced or transient medical staff• High risk of compassion fatigue and caregiver burden in the small community• Many participants travelled away from area for treatment |

| Mason and Hodgkin (2019) Rural Vic. | To explore how bereaved rural family palliative carers described their preparedness for caregiving. | 10 bereaved carers bereaved between 3-13 months Mixed life limiting illnesses (7) malignant (3) non-malignantNon-probability purposive sampling | Qualitative – PhenomenologyIn person semi- structured interviewsInterpretative phenomenological analysis | Small sample from spousal relationships. Recruitment by self-selection.Possible recall bias | 100% | • Into the unknown: issues around communication, poor prognosis, medical jargon, carer fear, unpredictable grief• Into the battle: intra-psychically (moral conflicts) inter-personally (support, respect, acknowledgment) & systemically in health system• Into the void: (isolation, abandonment, grief processing)• Into the good: positive affirmation, respect, acknowledgment helped to alleviate negative aspects of caring |

| McConigley et al. (2010) Metropolitan Perth & rural W.A. | To understand the experiences, support & informational needs of carers of people diagnosed with high-grade glioma | 21 current family carersHigh-grade glioma (HGG) Purposive sampling | Qualitative –Emergent qualitative design in grounded theory.Semi-structured interviews, 9 alone and 12 with the patient present at multiple time pointsData analysed by constant comparison method using QSR N7 software | Although participants were recruited from a single site, it treats most neurological cancers in WA. | 90% | • HGG patients’ sudden diagnosis gave carers little time to prepare for their caring role• Many carers struggled to care for themselves or seek respite• Carers needed support in decision-making/education at timely trajectory points• End of life discussions needs to be done early whilst the patient is still cognisant |

| McNamara and Rosenwax (2010) Metropolitan & rural W.A. | To understand the perceived needs of family carers looking after a palliating patient at end-of-life, their utilised supports and whether the support affected their ability to cope and their health after the death | 1071 bereaved family carersMultiple life limiting conditionsSampling method not identified | Mixed methods –Cross-sectional study using a retrospective cohort designData was obtained from administrative records from various services & triangulated against findings from semi-structured telephone interviews during which a survey was answered & expanded uponData was analysed by using logistic regression models | Potential recall bias. The participants’ needs were subjective, only medical records were objective | 100% | • Carer’s own resilience & coping mechanisms affected their ability to care and their health status• Many of the carers did not know the patient was so close to death, and opportunities for advance planning and financial discussions were lost. • 45.7% patients died in hospital, 31.5% at home, 16.9% in a hospice and 4.2% elsewhere• 24.7% of patients did not die where the carer wanted• 76.6% of carers stated they received enough support from health services• 23.1% carers stated they wanted more help with: information, hands-on-care, emotional support, night-time help, respite, transport, medication & spiritual support |

| O’Connor et al. (2009) Metropolitan Melbourne, Vic. | To explore the levels of satisfaction of carers who used a palliative homecare service | 300 bereaved carers responded to a postal surveyPlus 15 (7 bereaved carers, 3 current carers &5 staff nurses) participated in 3 separate focus groups 95% had advanced cancerSelf-selected, purposive, non-probability sampling | Mixed methods –Postal Survey and 3 separate focus groupsQuantitative data was analysed using summative descriptive statistics. Qualitative data was thematically analysed using Jacelon & O’Dell’s (2005) frameworkFocus group data was triangulated | All participants held private health insurance which may be comparable to other private but not public palliative homecare services. Unsure if findings from advanced cancer patients correlate to other life limiting illnesses | 100% | • Education around disease trajectory, medications & pain management was requested• Some carers wanted bereavement support from the known palliative care team not new counsellors• Carers suggested they would benefit from ongoing on-line support groups without having to leave home |

| Russell et al. (2008) Metropolitan Sydney, N.S.W. | To examine the views of family carers looking after a palliating dementia patient, to ascertain their perceptions of the patient’s QOL | 15 bereaved family carers DementiaPurposive sampling | Qualitative –Semi-structured in-depth interviews. Data analysed thematically | Small sample with subjective views of the family carers.The measurable indicators of QOL of the patient vary from carer to carer. | 90% | • Carers described QOL in 3 domains: the body; physical and social environments; and treatment with dignity and respect • Most carers felt that QOL ended when the patient lost body function control • Carers are the next best advocate for the patient who can no longer communicate their own wishes |

| Savage et al. (2015) Regional Vic. | To understand the carer’s views on managing the palliating patient’s diabetes at end of life and to explore what the carer needs in order to do this | 10 family carers (8 current, 2 bereaved) Diabetes and 9/10 patients also had cancerPurposive sampling | Qualitative –Semi-structured face-to-face interviewsData analysed thematically using the Ritchie & Spencer (1994) framework | Small cohort. Participants sourced from one palliative care service. 9/10 patients also had cancer thus limiting transferability | 90% | • Carers who had not previously managed the patient’s diabetes needed clear & simple instructions, plus a 24 hour hotline• Carers wanted BSL monitoring to continue, against medical direction |

| Sekelja et al. (2010) Metropolitan Sydney, N.S.W. | To investigate carers experiences of palliative care and their preference for timing of first contact | 30 bereaved carers. Metastic cancerSampling method not identified | Qualitative –Semi-structured telephone interviews.Interpretative phenomenological analysis | As carers received support from a variety of sources, they were not always aware of how/when they were receiving care from the palliative care team. | 90% | • Carers felt that first contact was best made after the patient had accepted pending death, but this was not ideal if made too late• Nothing could prepare the carers for the shock when the patient died• The stigma of palliative care as being ‘close to death’ was perceived by many carers |

| Wong and Ussher (2009) N.S.W. | To investigate bereaved carer’s positive experiences of providing palliative care at home | 22 bereaved carers CancerPurposive sampling | Qualitative –15 face to face & 8 telephone semi-structured interviews Retrospective study, part of a larger cross-sectional projectThematic analysis based on Braun & Clarke’s (2006) framework | In order to gain meaning from the palliating experience, carers may have reconstructed their memories more positively, thereby diminishing the negative aspects. | 90% | • There were positive aspects of caring for the dying patient• For many a ‘good death’ meant dying at home enabling others to say goodbye & participate in farewell activities • One third of patients died in hospital which the carers believed had advantages and if structured in a meaningful way still enabled a good death |

A two-stage process was undertaken in the selection of the papers for inclusion. Firstly, the lead author explored the literature, removed duplicates and then together both authors read the titles and abstracts and discarded the papers that did not comply with the inclusion criteria. Excluded papers included those wholly focussing on the experiences/opinions of medical staff, nurses, patients themselves or patients dying in hospital, the evaluation of tools or the examination of narrow aspects of caring or tasks. Five papers with mixed cohorts were retained as the voices of the carers were able to be separated out and were deemed valuable by both authors. Following reading the full texts of the remaining 22 papers, another seven papers were discarded (Figure 1). Two systematic reviews, which examined international literature, were discarded at this stage, but their reference lists were checked resulting in two extra papers being added that complied with the inclusion criteria. The search was repeated prior to publication; one paper met the inclusion criteria and was added to the final data set. Despite the focus of this systematic review being about the care of patients in their homes, one paper describing a rural setting examined the carers’ experiences when the patient transitioned from home to hospital and this was retained for its valuable insight. The Australian Caresearch database was also searched for grey literature on the topic of palliative care and carers but did not yield any papers that met the inclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Chart of Search Strategy.

Secondly, the final 17 papers were critiqued for rigour and quality using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2018) checklists for the appropriate methodologies. All attained a minimum score of 9 out of 10 points and were included in the final data set (Table 1).

The papers were analysed following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) 6 step inductive thematic approach which is to 1) become familiar with the data; 2) generate initial codes; 3) search for themes; 4) review themes; 5) define and name the themes and 6) produce the report. After re-reading the papers several times, the lead author created a detailed table highlighting each paper’s findings, and initial codes and comments were annotated against it. Both authors discussed, agreed upon and analysed the codes together resulting in the emergence of four themes.

Results

Of the 17 papers reviewed that constituted the final data set, there were 11 qualitative, three quantitative and three mixed methods papers, encompassing metropolitan, regional and rural studies in Victoria, New South Wales, South Australia and Western Australia. Two studies stated their face to face interviews were conducted with carers in the presence of the patient (Essue et al., 2015; McConigley et al., 2010). Bereaved carers were the focus of ten studies with predominantly current carers the focus of the remaining seven studies. Telephone interviews were employed by three of the studies (McNamara & Rosenwax, 2010; Sekelja et al., 2010; Wong & Ussher, 2009), but face to face interviews was the most commonly used data collection method. The papers covered a broad range of unspecified terminal diseases, cancers, neurodegenerative diseases, dementia and the complication of diabetes.

Four themes emerged from the review and the results will be presented under the four theme headings: 1) Perceived factors influencing caregiving; 2) Perceived impact and responses to caregiving; 3) Communication and information needs; and 4) Perceptions of current palliative support services and barriers to uptake.

Perceived Factors Influencing Caregiving

Carers noted that being able to adequately provide palliative care was affected by geographical distances between place of residence and health service provisions as well as being impacted by cultural issues. All carers described in the literature were impacted in many ways during the caring period, but those living in outer regional, rural or remote areas in Australia were greatly affected by service availability and geographical barriers. Part-time and/or inexperienced health professionals, lack of local referral knowledge and diagnostic delays or gaps in services caused difficulties for some regional and rural patients (Lee et al., 2009; Mason & Hodgkin, 2019) and time and money required for travelling into the city for appointments added to the carer’s burden (Hatcher et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2009; Mason & Hodgkin, 2019). Remote outback communities were also affected by seasonal weather patterns; roads could be cut off by heavy rains limiting service delivery during the wet season (Dembinsky, 2014).

Two studies described the impact of cultural issues on the palliative carers (Dembinsky, 2014; Heidenreich et al., 2014). Australia’s First Nation Yamatji women described dying in hospital without family present as ‘disgusting’ and against their cultural and spiritual beliefs, and this study showed a clear discrepancy between the cultural needs and rights of person-centred-care seen through the eyes of Australia’s First Nations people being cared for in a Western medical model (Dembinsky, 2014). The research also highlighted the meaning of a good death as being ‘in control’, which needed the co-operation of medical personnel in order to explain the disease trajectory in a timely manner, so the carer/patient could make informed decisions about whether to stay or return home to die (Dembinsky, 2014). The female carers from Chinese origin identified cultural barriers around disclosure of diagnosis and prognosis when providing palliative care (Heidenreich et al., 2014).

Perceived Impact and Responses to Caregiving

Fourteen of the 16 papers discussed the carers’ physical, emotional needs and/or health status as a result of undertaking the caring role (Aoun et al., 2010; Dembinsky, 2014; Essue et al., 2015; Hatcher et al., 2014; Heidenreich et al., 2014; Keesing et al., 2011; Kenny et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2009; Mason & Hodgkin, 2019; McConigley et al., 2010; McNamara & Rosenwax, 2010; O’Connor et al., 2009; Sekelja et al., 2010; Wong & Ussher, 2009). Carers reported fatigue and exhaustion and found it hard to balance all their normal roles, which for some included caring for elderly parents or grandchildren (Lee et al., 2009). The pressure of hands-on-care added to the desperate need for formal and informal respite (which could be limited) whether to catch up on sleep, shop or attend appointments (Hatcher et al., 2014; Mason & Hodgkin, 2019; McConigley et al., 2010; Sekelja et al., 2010). Seeking assistance was especially difficult for the carers of people with brain cancer as they refused to leave the care of the patient with inexperienced friends or neighbours due to the high risk of the patient seizing (McConigley et al., 2010). Acopia and symptom management were triggers for the person no longer remaining at home for care (Hatcher et al., 2014). Trying to honour the dying person’s wishes and make realistic end of life decisions caused moral distress for some carers (Mason & Hodgkin, 2019). Wong and Ussher (2009) stated that a ‘good death’ could be attained in hospital, if certain structures could be put into place and the hospital staff create a private environment in which to be able to say goodbye, under the direction of the carer.

Many carers felt disengaged when deprived of their usual routines even when the caring period was over. Disengagement was a result of deprivation of the carers’ usual routines and could be felt for some time after the end of the caring period (Keesing et al., 2011). When communication broke down, carers’ physical, psychological and emotional wellbeing was negatively impacted (Keesing et al., 2011). The financial study by Essue et al. (2015) highlighted the difficulty with completion of governmental forms for welfare assistance due to their complexity, inflexibility and difficulty for carers to access. Financial hardships, especially when the main income earner could no longer work (Essue et al., 2015) and deteriorating mental health due to unmet needs (Kenny et al., 2010) caused a further burden for carers.

As all carers coped differently due to their age, marital status, background, experiences, preparedness and resilience (Mason & Hodgkin, 2019; McNamara & Rosenwax, 2010), careful early assessment was needed in order to meet each carer’s unique needs (Aoun et al., 2010). Unmet needs prior to the death of the person receiving palliative care also compounded the carer’s grieving process for many carers (McNamara & Rosenwax, 2010).

Engaging in one’s own networks somewhat helped to ease the emotional burden that was carried by some of the carers (Hatcher et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2009). Living in a communal culture was another example of support (Dembinsky, 2014). In contrast, other carers reported that they did not, or could not ask for help due to embarrassment or cultural norms (Heidenreich et al., 2014; Keesing et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2009).

The ability to share their knowledge and understanding with others in similar circumstances provided satisfaction for some of the carers, but it was essential for them to remain emotionally supported to reduce the risk of compassion fatigue (Lee et al., 2009). This also became a method of coping as carers looked for positive and rewarding experiences throughout the caring process, which had the added benefit of deepening relationships and fostering personal growth (Wong & Ussher, 2009). Many carers suggested the benefits of using or developing new online social media platforms and tools to gain support, comfort, timely information and practical advice from their service providers and carer support groups (McConigley et al., 2010; O’Connor et al., 2009).

Communication and Information Needs

Ten of the 16 papers highlighted the need for carers to receive early and clear information about disease trajectory, daily tasks or financial planning (Dembinsky, 2014; Essue et al., 2015; Hatcher et al., 2014; Keesing et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2009; McConigley et al., 2010; Mason & Hodgkin, 2019; McNamara & Rosenwax, 2010; O’Connor et al., 2009; Savage et al., 2015). Information needed to be delivered using language carers could understand (Mason & Hodgkin, 2019) and in increments so as not to overwhelm them by providing more than they could absorb (McConigley et al., 2010). Perceived gaps in patient education from health professionals often triggered the act of scouring the internet for information regarding the person’s disease and its trajectory, which had the potential to produce negative material (Lee et al., 2009). Mason and Hodgkin (2019) reported many carers felt let down by health professionals when prognostic information was untimely, inaccurate or delivered poorly, resulting in feeling unprepared or supported in their caring role.

Hatcher et al. (2014) reported that communication was improved after the implementation of a new model between a rural community palliative service and the local hospital during the admission process. This involved a handover from one of the community palliative care nurses whom then ‘followed the patient’ by joining the inpatient care team when the patient was admitted to hospital.

Seven out of the 16 studies (Dembinsky, 2014; Hatcher et al., 2014; Keesing et al., 2011; Mason & Hodgkin, 2019; Russell et al., 2008; Savage et al., 2015; Wong & Ussher, 2009) discussed the importance of listening to the carer’s views highlighting the importance of good communication between the team and the carer to avoid disempowerment (Keesing et al., 2011). Despite many carers wanting to be acknowledged as being an integral part of the team and referred to and involved in all aspects of decision making (which Mason & Hodgkin (2019) found helped alleviate some of the negative impacts of caring), this did not always occur. This was especially important for the carers looking after people with dementia. These carers reported being an advocate and voice and had to separate what they, as the carer wanted, and what they believed the patient themselves would want (Russell et al., 2008).

Perceptions of Current Palliative Support Services and Barriers to Uptake

The views about palliative support services and/or barriers to uptake were discussed in ten of the 16 papers (Aoun et al., 2010; Dembinsky, 2014; Heidenreich et al., 2014; Keesing et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2009; McNamara & Rosenwax, 2010; O’Connor et al., 2009; Sekelja et al., 2010; Wong & Ussher, 2009). Some of the advantages of the early introduction to palliative support services included forward planning of available services, the commencement of end of life discussions and strategies and the early preparation of a ‘good death’ (Aoun et al., 2010; Keesing et al., 2011). Another advantage of the palliative support service was the dissemination of information around how to handle medications and what to look for when death was imminent (McNamara & Rosenwax, 2010).

Many carers viewed palliative support services as a death sentence being accessed only by people at the end of life or when the carers could no longer cope (Dembinsky, 2014; Lee et al., 2009; Sekelja et al., 2010). While for others the engagement occurred after the hope of a cure was exhausted and acceptance of the pending death occurred (Lee et al., 2009; Sekelja et al., 2010). In retrospect, some carers wished they had availed themselves of palliative support services earlier in the disease trajectory (Lee et al., 2009). Some carers were dissatisfied with the referral process, lack of continuity of staff or the lack of time to talk to health professionals and stated services between providers was poorly co-ordinated, inadequate and/or lacking bereavement services (Lee et al., 2009; Mason & Hodgkin, 2019; McNamara & Rosenwax, 2010; O’Connor et al., 2009; Sekelja et al., 2010).

Some carers reported forming strong bonds of trust and respect with the palliative support team which was beneficial to the grieving process when extended into the bereavement period (Sekelja et al., 2010; Wong & Ussher, 2009) but emotional hardship occurred if this relationship ceased when the person died (O’Connor et al., 2009). One study reported that the social aspect of the nurse’s visits assisted the person receiving palliative care with motivation to get up and dressed that day (Sekelja et al., 2010).

The study involving female carers from Chinese origin, found cultural and social values created strong barriers to the uptake of palliative care and other support services (Heidenreich et al., 2014). The Chinese culture with its norms around not shaming the family, saving face and the expectation of women performing the caring role, prevented these carers from obtaining respite or other forms of assistance either formally or from other members of the family, subsequently leaving them feeling isolated, lonely and not coping (Heidenreich et al., 2014). Similarly, Australia’s First Nation Yamatji women reported that the desire to die ‘in country’ was a major barrier for their low palliative service uptake, compounded by limited services and trained staff that could attend to patients in remote outback communities (Dembinsky, 2014). Loud cultural expressions of grief, cleansing ceremonies and limitations of space were also at odds with the expectations of an inpatient palliative setting (Dembinsky, 2014).

Discussion

Seventeen papers were reviewed, examining the needs of carers who were providing palliative care in their homes in Australia which the authors believe to be the only systematic literature review examining just Australian literature between 2008-2020 on this topic. The results of this review demonstrated that a variety of physical and emotional supports, good communication and being involved in decision making were essential to enable the carers to continue their supportive role at home. These supports were provided by formal palliative care services (both public and private), family, friends, neighbours and online support groups. Sharing their experiences and knowledge also provided a positive sense of satisfaction for some of the carers. The provision of accurate and timely information was essential but nevertheless carers used the internet and support groups as another means of information. The focus of this review was not to compare palliative support service providers or metropolitan, regional or rural zones per se, but to hear from carers across the country. Nevertheless, services were more limited in size and had to extend their reach further, the more rural the carer and family lived. Only one study examined Australia’s First Nations people in ‘Yamatji country’ in W.A. (Dembinsky, 2014). Considering the enormous land mass of Australia, those living outside metropolitan areas had the added burden of geographical, logistical and financial issues including fewer services, gaps between visits and transient health providers. Whilst not all states were represented in the literature, many of the carers’ needs appeared to be universal.

Cultural differences could be seen between the female carers from Chinese origin and Australia’s First Nations Yamatji women regarding conversations around palliative care within their families. The familial culture imposed a heavy burden created by secrecy for the Chinese carers. On the other hand, Australia’s First Nations people were very communal and shared all stories and news amongst their communities, wanting family by the bedside and to be able to undertake important ceremonial rituals.

Whilst it is well known that carers need a variety of supports along the illness trajectory, the literature highlighted that often carers were reluctant to engage in palliative support services early and in hindsight wished they had. One explanation for this could be the community perceptions and stigma around the definitions of end of life care and palliative care, which is at odds with formal definitions (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2015).

Limitations

There were some limitations amongst the papers in this review. Some of the papers included findings from a variety of disease processes therefore generalisation is not possible nor are results from small sample sizes. The bereaved carers may have reconstructed their experiences more positively over time as a coping mechanism both in their general outlook and of their views of the palliative support services they used. Each of the five studies with mixed cohorts labelled their quotations but it became difficult to decipher the ownership of different opinions in their discussion sections. It is unknown whether those carers who were interviewed in front of the patient, were able to speak freely or not, and this may have impacted their findings. Recruitment methods of participants varied between government data sources, palliative care service records and advertising material which provided a cross section of the carer population which may add to the strength of the results.

Implications for Practice

It would be helpful for health professionals to commence early education around the concept of palliative care to remove unnecessary stigmas and foster earlier acceptance of pathways and services that may assist the carer in the future. Carers would benefit from financial planning advice, budgeting strategies and assistance in navigating welfare support and services as soon as they engage in palliative care. Community palliative care nurses who spend a lot of time with palliative patients’ families, may be best placed to initiate conversations about current and future palliative care needs and generate referrals for other supports. Further research is needed to understand how different funding models between the states affect palliative service provision and to evaluate the use of palliative services by Australia’s First Nation peoples across the country.

Conclusion

This systematic review highlights the gap in the literature examining Australian original research published between 2008 and 2020 on the topic of understanding the needs of carers of adults receiving palliative care in the home in Australia. It highlights that multiple support systems are needed to support the carer to enable them to undertake their role. Carers need to be supported both physically and emotionally, including timely respite, practical assistance, education and bereavement care. Many carers who used formal palliative support services were very satisfied with the care provided to both themselves and the patient, but social stigma around the meaning of palliative care, cultural barriers or geographical issues were some reasons for poor uptake of support services. An early understanding of the disease trajectory and what to expect on the caring journey would assist the carers to prepare ahead, both physically and emotionally. Open and clear communication between all parties would enable carers to feel validated, empowered and an important part of the team, thus enabling them to continue their role of providing palliative care in the home which would in turn, reduce the burden on the health system.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-son-10.1177_2377960820985682 for Understanding the Needs of Australian Carers of Adults Receiving Palliative Care in the Home: A Systematic Review of the Literature by Elizabeth M. Miller BN (Hons.), RN Joanne E. Porter PhD, MN, Grad Dip CC, Grad Cert Ed, Grad Dip HSM, BN, RN in SAGE Open Nursing

Acknowledgments

The lead author searched and screened the literature, then coded, analysed and drafted the manuscript. This work formed part of the lead author’s Bachelor of Nursing (Honours) thesis. The second author assisted with project design, screening, analysis and edits of the manuscript and supervised throughout the project. Both authors have contributed to the drafting of the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Elizabeth M. Miller https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0767-5460

Joanne E. Porter https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1784-3165

References

- Aoun S., McConigley R., Abernethy A., Currow D. C. (2010). Caregivers of people with neurodegenerative diseases: Profile and unmet needs from a population-based survey in South Australia. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 13(6), 653–661. 10.1089/jpm.2009.0318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2013). Commonwealth of Australia. Population projections, Australia, 2012 (base) to 2101 (ABS Cat. No. 3220.0). https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/older-people/older-australia-at-a-glance/contents/demographics-of-older-australians/australia-s-changing-age-and-gender-profile.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2020). Commonwealth of Australia. Population clock. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/94713ad445ff1425ca25682000192af2/1647509ef7e25faaca2568a900154b63?OpenDocument

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2015). National consensus statement: Essential elements for safe and high-quality end-of-life care. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/National-Consensus-Statement-Essential-Elements-forsafe-high-quality-end-of-life-care.pdf

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2016. a). End of life care. Australia’s health 2016 (Australia’s health series no. 15 Cat. No. AUS 199). https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/68ed1246-886e-43ff-af35-d52db9a9600c/ah16-6-18-end-of-life-care.pdf.aspx.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2016. b). How does Australia’s health system work? (Australia’s health series no. 15 Cat. No. AUS 199). https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/f2ae1191-bbf2-47b6-a9d4-1b2ca65553a1/ah16-2-1-how-does-australias-health-system-work.pdf.aspx

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitive Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burns C. M., Abernethy A. P., Leblanc T. W., Currow D. C. (2011). What is the role of friends when contributing care at the end of life? Findings from an Australian population study. Psycho-oncology, 20(2), 203–212. 10.1002/pon.1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Australia. (2020). Department of the prime minister and cabinet. Closing the gap report, 2020. Annual report to parliament on progress in closing the gap. https://ctgreport.niaa.gov.au/

- Critical Appraisal Skills Program. (2018). CASP checklists. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- Dembinsky M. (2014). Exploring Yamatji perceptions and use of palliative care: An ethnographic study. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 20(8), 387–393. 10.12968/ijpn.2014.20.8.387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2020). Medicare. https://www.health.gov.au/health-topics/medicare

- Essue B. M., Beaton A., Hull C., Belfrage J., Thompson S., Meachen M., Gillespie J. A. (2015). Living with economic hardship at the end of life. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 5(2), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher I., Harms L., Walker B., Stokes S., Lowe A., Foran K., Tarrant J. (2014). Rural palliative care transitions from home to hospital: Carers' experiences. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 22(4), 160–164. 10.1111/ajr.12105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidenreich M. T., Koo F. K., White K. (2014). The experience of Chinese immigrant women in caring for a terminally ill family member in Australia. Collegian, 21(4), 275–285. 10.1016/j.colegn.2013.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keesing S., Rosenwax L., McNamara B. (2011). 'Doubly deprived': A post-death qualitative study of primary carers of people who died in Western Australia. Health and Social Care in the Community, 19(6), 636–644. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.01005.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny P. M., Hall J. P., Zapart S., Davis P. R. (2010). Informal care and home-based palliative care: The health-related quality of life of carers. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 40(1), 35–48. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.11.322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. F., O'Connor M. M., Chapman Y., Hamilton V., Francis K. (2009). A very public death: Dying of mesothelioma and asbestos-related lung cancer (M/ARLC) in the Latrobe Valley, Victoria, Australia. Rural and Remote Health, 9(3), 1183. 10.1645/GE-2202.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A., Altman D. G., Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gøtzsche P. C., Ioannidis J. P. A., Clarke M., Devereaux P. J., Kleijnen J., Moher D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), e1–e34. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason N., Hodgkin S. (2019). Preparedness for caregiving: A phenomenological study of the experiences of rural Australian family palliative carers. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(4), 926–935. 10.1111/hsc.12710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConigley R., Halkett G., Lobb E., Nowak A. (2010). Caring for someone with high-grade glioma: A time of rapid change for caregivers. Palliative Medicine, 24(5), 473–479. 10.1177/0269216309360118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara B., Rosenwax L. (2010). Which carers of family members at the end of life need more support from health services and why? Social Science & Medicine, 70(7), 1035–1041. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation. (2020). Aboriginal health history. https://www.naccho.org.au/about/aboriginal-health-history/

- National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling. (2004). Who’s going to care? Informal care and an ageing population. http://www.natsem.canberra.edu.au/publications/?publication=whos-going-to-care-informal-care-and-an-ageing-population.

- O’Connor L., Gardner A., Millar L., Bennett P. (2009). Absolutely fabulous—But are we? Carers’ perspectives on satisfaction with a palliative homecare service. Collegian, 16(4), 201–209. 10.1016/j.colegn.2009.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palliative Care Victoria. (2017). Ensuring Victorians can access palliative care and end of life care—When and where it is needed [online brochure]. https://pallcarevic.asn.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/PCV-Seeks-65M-for-Palliative-Care-A4.pdf

- Ritchie, J., & Spencer, L. (1994). Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In A. Bryman & R. Burgess (Eds)., Analysing Qualitative Data (pp. 173–194) Routledge.

- Russell C., Middleton H., Shanley C. (2008). Research: Dying with dementia: The views of family caregivers about quality of life. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 27(2), 89–92. 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2008.00282.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage S., Dunning T., Duggan N., Martin P. (2015). The experiences and needs of family carers of people with diabetes at the end of life. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing, 17(4), 293–300. 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000162 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sekelja N., Butow P., Tattersall M. (2010). Bereaved cancer carers’ experience of and preference for palliative care. Supportive Care in Cancer, 18(9), 1219–1228. 10.1007/s00520-009-0752-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong W. K. T., Ussher J. (2009). Bereaved informal cancer carers making sense of their palliative care experiences at home. Health & Social Care in the Community, 17(3), 274–282. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00828.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2018, February). Palliative care. https://who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-son-10.1177_2377960820985682 for Understanding the Needs of Australian Carers of Adults Receiving Palliative Care in the Home: A Systematic Review of the Literature by Elizabeth M. Miller BN (Hons.), RN Joanne E. Porter PhD, MN, Grad Dip CC, Grad Cert Ed, Grad Dip HSM, BN, RN in SAGE Open Nursing