Abstract

Background:

Comorbidity of substance use disorders (SUDs) with mood disorders and other psychiatric conditions is common. Parenting processes and family functioning are impaired in adolescents with SUDs and mood disorders, and parent/family factors predict intervention response. However, limited research has examined the relationship between parent/family factors and mood symptom treatment response in adolescents with comorbid SUDs and psychiatric conditions.

Method:

This study examined the predictive effects of parenting processes and family functioning on depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation (SI) in a randomized controlled trial of integrated cognitive-behavioral therapy vs. treatment as usual for 111 adolescents with comorbid SUDs and psychiatric disorders. Measures of parenting processes, family functioning, depressive symptoms, and SI were completed at baseline and 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-ups. Exploratory analyses involved mixed-effects regression models.

Results:

Across treatment conditions, depressive symptoms and SI improved over 12 months. Family functioning domains of family roles (d=0.47) and affective involvement (d=0.39) significantly improved across treatment conditions over 12 months. Higher baseline parental monitoring predicted improved trajectory of depressive symptoms (d=0.44) and SI (d=0.46). There were no significant predictive effects for baseline family functioning or other parenting processes (listening, limit setting).

Limitations:

Limitations include the modest sample, attrition over follow-up, and generalizability to samples with higher rates of mood disorders and/or uncomplicated mood disorders.

Conclusions:

Parental monitoring may be an important prognostic indicator of depressive symptoms and SI in adolescents with co-occurring SUDs and psychiatric conditions, and therefore may be useful to assess and target in treatment, in addition to family functioning.

Keywords: adolescents, parenting, substance use disorder, depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, treatment predictors

Introduction

Substance use disorders (SUDs) and psychiatric conditions commonly co-occur in adolescence, with comorbidity rates ranging from 60-80% (Armstrong and Costello, 2002; Grella et al., 2004; Rowe et al., 2004). Comorbidity is associated with a more severe course of illness, including suicide attempts/death by suicide (Brent et al., 1993; King et al., 1996), aggression, and high-risk criminal behavior in young adulthood (Clingempeel et al., 2008). In addition, comorbidity complicates treatment and has been associated with poorer intervention response (Grella et al., 2004; Rowe et al., 2004; Shane et al., 2003; Tomlinson et al., 2004).

Comorbidity of SUDs with mood disorders in particular, including depression and bipolar disorders, is prevalent and poses unique challenges. Approximately 20-30% of adolescents who report substance use have comorbid depression (Armstrong and Costello, 2002), and co-occurrence rates of SUDs and bipolar disorders range from 16-39% (Goldstein and Bukstein, 2010). Comorbid depression and SUDs are associated with more severe mood symptoms (Swendsen et al., 1998), longer duration of illness (Merikangas et al., 2003), suicide attempts (Wagner et al., 1996), and greater healthcare utilization (Lewinsohn et al., 1994). In addition, co-occurring depression and SUDs are predictive of greater treatment attrition (Pirkola et al., 2011), smaller psychological and physical health gains following treatment (Hersh et al., 2014), and longer time to recovery (Rohde et al., 2001). Co-occurring SUDs and bipolar disorders are associated with similar detrimental sequalae, including presence of conduct disorder, suicide attempts, legal problems, academic failure, shorter time to recurrence, and treatment non-adherence (DelBello et al., 2007; Goldstein et al., 2008; Wilens et al., 2009).

Thus, comprehensive interventions are needed to address the unique challenges and etiological factors common across SUDs and mood disorders in adolescence. Risk factors for SUDs, mood disorders, and their comorbidity include impaired parenting and family functioning. For example, families of adolescents with or at risk for depression present with high levels of conflict, anger, criticism, harsh parenting, and hostility; low levels of cohesion, support, and warmth; and problematic parenting styles, practices, and communication (Beardslee et al., 1998; Bodner et al., 2018; Garber, 2006; Milevsky et al., 2007; Sander and McCarty, 2005; Sheeber et al., 2007; Van Loon et al., 2014). Families of youth with bipolar disorders also display high levels of conflict, control, aggression, quarreling, forceful punishment, tension, stress, and negative expressed emotion; low levels of warmth, affection, intimacy, cohesion, adaptability, expressiveness, organization, and positive expressed emotion; and impaired functioning overall (Belardinelli et al., 2008; Keenan-Miller et al., 2012; MacPherson et al., 2018; Nader et al., 2013; Perez Algorta et al., 2018; Schenkel et al., 2008; Sullivan et al., 2012).

Although no strong and consistent risk factors for long term prediction of suicidality have emerged (Franklin et al., 2017), some research suggests that poor family functioning (e.g., impaired family problem solving, family conflict, and low levels of parental support) confers exacerbated short term risk for suicidal ideation (SI) and behavior in adolescence (King and Merchant, 2008; Wagner et al.,2003). Similarly, there are several parenting and family risk factors for SUDs in adolescence, including ineffective parent-adolescent communication, poor parental monitoring and supervision, lack of parental involvement in adolescents’ activities and peer relationships, minimal parental social support, impaired parenting/family management strategies, high levels of parental disapproval, increased familial stress, and parental modeling of substance use (Barnes and Farrell, 1992; Calafat et al., 2014; Chilcoat and Anthony, 1996; Fallu et al., 2010; Hawkins et al., 1992; Mares et al., 2011; van der Vorst et al., 2006). Thus, while there are unique impairments across adolescent mood disorders and SUDs, some deficits in parenting and family functioning are shared and represent important treatment targets.

Indeed, evidence-based treatments (EBTs) for adolescents with mood disorders and SUDs typically incorporate individual and parent/family components. This is true of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal psychotherapy, two EBTs with the strongest empirical support for the treatment of adolescent depression (Weersing et al., 2017). Similarly, family psychoeducation plus skill-building (incorporating CBT) is recommended for youth with bipolar disorders (Fristad and MacPherson, 2014). In addition, ecological family-based and multi-component treatments involving family skill-building lead to improvements in alcohol/substance use and both internalizing and externalizing symptoms in adolescents with SUDs (Hogue et al., 2018).

Importantly, parent and family factors have been found to influence treatment response in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of psychotherapy for mood disorders and SUDs. For adolescents with depression, high parent-child conflict and poor family environments are predictive of treatment nonresponse (Asarnow et al., 2009; Birmaher et al., 2000; Feeny et al., 2009; Gunlicks-Stoessel et al., 2010). For youth with bipolar disorders, parental psychiatric symptoms and impairments in family expressed emotion, cohesion, adaptability, and conflict are associated with poorer mood symptom treatment outcomes (Keenan-Miller et al., 2012; MacPherson et al., 2014; Miklowitz et al., 2009; Sullivan et al., 2012; Weinstein et al., 2015). Only one study has examined family interaction processes in a comorbid sample, which found that low family cohesion predicted nonresponse for depressive symptoms among adolescents with comorbid SUDs and depression (Rohde et al., 2018).

Whereas the adolescent mood disorders treatment literature has primarily focused on family interaction factors as predictors of treatment outcome, parenting variables have been consistently documented as risk (e.g., modeling of substance use) and protective (e.g., monitoring) factors for substance use in adolescence (Chilcoat and Anthony, 1996; Westling et al., 2008). However, no studies have examined the influence of parenting factors on mood symptom treatment response for adolescents with co-occurring SUDs and psychiatric disorders. Such information is important, as the identification of treatment predictors can determine parenting prognostic indicators for adolescents who may respond more favorably to interventions versus those who may require additional supports. Such information could lead to the optimization and personalization of treatments, and the development of novel adjunctive interventions to target specific parent/family impairments that may hinder response to existing psychotherapies.

To address this gap in knowledge, the present study examined whether family functioning and parenting processes (as a specific aspect of family interactions) predicted depressive symptoms and SI in adolescents with co-occurring SUDs and psychiatric disorders in a community mental health clinic (CMHC). These adolescents participated in an RCT of an adapted version of integrated cognitive-behavioral therapy (I-CBT) versus treatment as usual (TAU), where adolescents who received I-CBT had slightly better substance use outcomes, but there were no statistically significant differences between conditions on psychiatric symptoms (externalizing problems, anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms) (Wolff et al., 2020).

Given limited research on family functioning and parenting processes as predictors of depressive symptoms and SI in adolescents with co-occurring SUDs and psychiatric disorders, our hypotheses and analyses were considered exploratory. We expected that adolescents with less impaired family functioning and whose parents displayed higher levels of monitoring, listening, and limit setting would demonstrate improved trajectory of depressive symptoms and SI after treatment across a 12-month follow-up period compared to adolescents with more impaired family functioning and parenting practices. Exploratory analyses also examined change in family functioning and parenting processes over 12-month follow-up.

Method

Participants

Participants included 111 adolescents and their families who were referred for treatment and recruited from a CMHC in the Northeastern United States. Inclusion criteria were: 1) enrollment in the Intensive Outpatient Home-based Program (IOP) for co-occurring disorders at the CMHC; 2) aged 12-18 years; 3) endorsement of alcohol and/or other substance use in the prior three months; and 4) English speaking. Exclusion criteria included: 1) serious psychotic symptoms (e.g., hallucinations) or a primary diagnosis of an eating disorder or obsessive-compulsive disorder; and 2) acute suicidal or homicidal ideation/behavior requiring higher levels of care.

Procedure

This study was approved by the hospital and university human subjects’ protection committees. All adolescents and their parent or legal guardian who presented for treatment at the CMHC’s IOP were invited to participate in a two-group randomized parallel trial, if they met the aforementioned inclusion/exclusion criteria. Research assistants described the study to families and then obtained written informed consent and assent from parents and adolescents, respectively. Subsequently, a baseline assessment battery was administered. Follow-up assessments were completed at 3, 6, and 12 months by research assistants blind to treatment condition. Participants received compensation for each assessment visit. Transportation costs were covered as needed.

Treatment Conditions

After completion of the baseline assessment, families were assigned to treatment condition (I-CBT or TAU). The study was conducted under ecologically valid conditions (i.e., session length and frequency varied based on clinical presentation and insurance coverage). Treatment was approved by insurers, on average, for 12 weeks. Following standard clinic procedures, adolescents could be concurrently referred and evaluated for medication by clinic psychiatrists. Therapists in both conditions were master’s level staff hired by the clinic. They met weekly with the onsite master’s-level supervisor who provided clinical supervision and case management oversight. Therapists in the experimental condition received weekly supervision by one of four study supervisors (JW, EF, CES, AS).

Details of the treatment conditions are described in the primary outcomes paper (Wolff et al., 2020). Briefly, the experimental condition (I-CBT) included individual adolescent (e.g., problem-solving, cognitive restructuring, behavioral activation, affect regulation), parent (e.g., contingency management, monitoring), and family (e.g., communication, family problem-solving) sessions. In the TAU condition, therapists used practitioner-based principles common to the CMHC (i.e., the use of eclectic, flexible treatment including supportive therapy, advice, skill discussion, and establishing a positive relationship). TAU therapists could also use CBT techniques as well as parent and family sessions at their discretion, in addition to any other strategies they deemed appropriate.

Measures

The diagnostic interview was administered at baseline. Measures of parenting processes, family functioning, and adolescents’ depressive symptoms and SI were administered at baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months.

Psychiatric Diagnoses.

The Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia- Present Version (K-SADS-P) (Kaufman et al., 1997), a semi-structured diagnostic interview based on DSM-IV criteria, was administered separately to parents and adolescents to assess adolescents’ psychiatric and substance use diagnoses. Clinician summary scores/diagnoses incorporating parent and adolescent report were used in this study. A second clinician rated 20% of all K-SADS-P interviews and reliability was excellent. There was 100% agreement on six diagnoses, including major depressive disorder, while agreement ranged from 89% to 95% for the remaining psychiatric and substance use diagnoses.

Observational Coding of Parenting Processes.

The videotaped Family Assessment Task (FAsTask) (Dishion et al., 2003) was used to assess parenting processes within family interactions. Norms for the task were derived from 120 multi-ethnic families whose children had good school attendance and no disruptive problems in school (Dishion et al., 2003). Two FAsTask scenarios, 5 minutes each, were examined. In the Monitoring and Listening task, the adolescent was instructed by research staff to lead a discussion about a time spent without supervision and parent(s) were instructed to seek additional information about the situation the adolescent presented. In the Limit Setting task, parents and adolescents were instructed to talk about a limit that had to be set within the last month and discuss how it was resolved and how it would be resolved if it were to occur again in the future.

A trained coder completed ratings for each task. Individual items were rated on a 9-point scale (1=not at all to 9=very much), with higher scores reflecting greater levels of monitoring, listening, and limit setting. A total score was generated for each of these three domains via an average of subscale items. When both parents participated in the FAsTask, we averaged across both parents to represent the contribution of each parent. Approximately 20% of recordings were double coded to calculate interrater reliability. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for the two raters were .96 for monitoring and .95 for limit setting for the family as a whole. For parents, ICCs were .89 for monitoring, .94 for listening, and .98 for limit setting. Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .59 to .88.

Self-Report of Parenting Processes.

The 9-item Parental Monitoring subscale of the Parental Monitoring Questionnaire (PMQ) (Stattin and Kerr, 2000) was used to assess self-reported degree of parental monitoring. Parents were asked to rate knowledge of adolescent whereabouts and various daily activities. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Scores range from 9-45; higher scores indicate greater levels of monitoring. This subscale has demonstrated adequate internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and validity (Stattin and Kerr, 2000). In the current study, baseline internal consistency was high (α=.88).

Family Functioning.

Family functioning was assessed via parent report on the Family Assessment Device (FAD) (Epstein et al., 1983), consisting of 60 items and seven subscales: Problem Solving; Communication; Roles; Affective Responsiveness; Affective Involvement; Behavior Control; and General Functioning. Items are averaged to produce a summary score for each subscale ranging from 1-4; higher scores indicate poorer functioning, and scores >2 suggest clinical severity. The FAD has demonstrated good reliability and validity across ages and populations (Miller et al., 1985; Youngstrom et al., 2011). In the current study, baseline internal consistency was high (α=.92).

Depressive Symptoms.

The Children’s Depression Inventory-2 (CDI-2) (Kovacs, 2010) is a 28-item, self-report measure of depressive symptoms over the prior two weeks, rated on a 3-point Likert scale. The total raw score ranges from 0-56, with higher scores indicative of greater depressive symptom severity. The CDI-2 has demonstrated good reliability and validity in clinical samples (Masip et al., 2010). Clinical cutoff scores between 13 to 20 have been suggested. In the current study, baseline internal consistency was high (α=.91).

Suicidal Ideation.

To assess the severity and frequency of SI, adolescents were administered the 15-item Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (SIQ)-Jr (Reynolds and Mazza, 1999). Items are scored from 0 (never) to 6 (almost every day) for a possible range of 0–90. Total scores include a sum of all items, with higher scores indicating greater severity. A score of 31 is considered a clinical cutoff. In the current study, baseline internal consistency was high (α=.95).

Analytic Strategy

The primary outcomes paper for this RCT found that adolescents who received I-CBT had slightly better substance use outcomes, but there were no statistically significant differences between conditions on psychiatric symptoms (externalizing problems, anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms) (Wolff et al., 2020). Trajectory for depressive symptoms via the CDI-2 was reported in the prior publication; trajectory for SI via the SIQ is newly reported in the current manuscript.

Analyses examining baseline family and parenting predictors of depressive symptoms and SI across treatment conditions were conducted in SPSS 25 with two-tailed comparisons (p<.05). First, descriptive statistics were calculated to characterize the sample. Then, two-level mixed-effects regression models (MRMs) were conducted with repeated measures at level one nested within participant at level two to examine the relationship of family functioning and parenting processes with depressive symptoms and SI (Singer and Willett, 2003). Random effects for intercepts and slopes were modeled using unstructured covariance matrices and retained when significant and/or when significantly improving model fit. Conditional growth models included effects for Time (centered at baseline), Family Functioning/Parenting Processes, and the Family Functioning/Parenting Processes x Time interaction. Baseline depressive symptoms and SI were included as covariates to examine whether family functioning/parenting processes predicted subsequent symptom course above and beyond existing depressive symptoms and SI. Baseline levels of family functioning, parenting processes, depressive symptoms, and SI were mean-centered prior to addition to models.

Given the exploratory nature of analyses, a step-up model building strategy was used (Singer and Willett, 2003). Two final models were computed examining the relationship of family functioning (problem solving, communication, roles, affective responsiveness, affective involvement, behavior control, general functioning) and parenting processes (monitoring, listening, limit setting) with: 1) depressive symptoms; and 2) SI. Mean baseline ratings for FAD family functioning subscales; FAsTask parental monitoring, listening, and limit setting; and PMQ monitoring were examined as predictors of intercept and slope. Prospective, longitudinal CDI-2 depressive symptoms and SIQ SI were dependent variables. If predictors were not significant and/or did not improve model fit, they were removed from subsequent analyses and final models.

Exploratory analyses also used two-level MRMs to examine change in family functioning and parenting processes over time. As noted above, random effects for intercepts and slopes were modeled using unstructured covariance matrices and retained when significant and/or when significantly improving model fit. In these MRMs, conditional growth models included effects for Time (centered at baseline), Treatment Group (I-CBT vs. TAU), and the Treatment Group x Time interaction.

Results

Sample Composition

The sample was diverse and from an economically disadvantaged background (Table 1). The majority were male (57.66%) and White (72.90%), with approximately one-third (31.48%) identifying as Latinx. Over one quarter identified as LGBTQ (28.38%) and nearly half (44.44%) reported family income less than $26,000/year.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic, Clinical, Parenting, and Family Characteristics

| Variable |

N=111 |

|---|---|

| M(SD) or n(%) | |

| Demographics | |

| Age, M(SD) | 15.73(1.19) |

| Sex (Male), n(%) | 64(57.66%) |

| Sexual Orientation (Heterosexual), n(%) | 53(71.62%) |

| Race | |

| White, n(%) | 78 (72.90%) |

| Black or African American, n(%) | 12 (11.21%) |

| Multiracial, n(%) | 13(12.15%) |

| Other, n(%) | 4(3.74%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Latinx, n(%) | 34(31.48%) |

| Parental Income | |

| 0 to $25,999, n(%) | 48(44.44%) |

| $26,000 to $49,999, n(%) | 32(29.63%) |

| $50,000 or more, n(%) | 28(25.93%) |

| Continuous Clinical Characteristics | |

| CDI-2 Depressive Symptoms, M(SD) | 16.66(10.10) |

| SIQ Suicidal Ideation, M(SD) | 17.01(19.07) |

| FAsTask Parenting Processes | |

| Listening, M(SD) | 7.42(1.20) |

| Limit Setting, M(SD) | 6.32(1.54) |

| Monitoring, M(SD) | 4.74(1.48) |

| PMQ Parental Monitoring | |

| Monitoring, M(SD) | 29.67(7.57) |

| FAD Family Functioning | |

| Problem Solving, M(SD) | 2.14(0.42) |

| Communication, M(SD) | 2.17(0.39) |

| Roles, M(SD) | 2.45(0.39) |

| Affective Responsiveness, M(SD) | 2.05(0.49) |

| Affective Involvement, M(SD) | 2.32(0.49) |

| Behavior Control, M(SD) | 1.86(0.41) |

| General Functioning, M(SD) | 2.11(0.49) |

Note. CDI-2=Children’s Depression Inventory-2; SIQ=Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire; FAsTask= Family Assessment Task; PMQ=Parental Monitoring Questionnaire; FAD=Family Assessment Device.

Psychiatric and substance use diagnoses were also prevalent and varied (Table 2). The most common psychiatric diagnoses were oppositional defiant disorder (63.96%), major depressive disorder (57.66%), conduct disorder (55.86%), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (54.05%), and generalized anxiety disorder (33.33%). In this study adolescents could receive concurrent diagnoses of oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. Regarding substance use, marijuana abuse (83.78%), marijuana dependence (60.36%), and alcohol abuse (32.43%) were the most prevalent.

Table 2.

Baseline Psychiatric Diagnoses

| K-SADS-P DSM-IV Diagnoses |

N=111 |

|---|---|

| n(%) | |

| Mood Disorders | |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 64(57.66%) |

| Depressive Disorder Not Otherwise Specified | 5(4.50%) |

| Dysthymia | 4(3.60%) |

| Bipolar Disorder Not Otherwise Specified | 2(1.80%) |

| Bipolar I Disorder | 1(0.90%) |

| Anxiety Disorders | |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 37(33.33%) |

| Social Anxiety Disorder | 22(19.82%) |

| Panic Disorder without Agoraphobia | 3(2.70%) |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | 2 (1.80%) |

| Agoraphobia | 1(0.90%) |

| Specific Phobia | 1(0.90%) |

| Traumatic Stress Disorders | |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder | 22(19.82%) |

| Acute Stress Disorder | 1(0.90%) |

| Disruptive Behavior Disorders | |

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 71(63.96%) |

| Conduct Disorder | 62(55.86%) |

| Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder | 60(54.05%) |

| Substance Abuse/Dependence | |

| Marijuana Abuse | 93(83.78%) |

| Marijuana Dependence | 67(60.36%) |

| Alcohol Abuse | 36(32.43%) |

| Other Substance Abuse | 19(17.12%) |

| Alcohol Dependence | 17(15.32%) |

| Other Substance Dependence | 15(13.51%) |

| Other Disorders | |

| Psychosis | 1(0.90%) |

| Bulimia | 1 (0.90%) |

Note. K-SADS-P=Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Present Version; DSM-IV=Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition. In this study adolescents could receive concurrent diagnoses of oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder.

On continuous measures, adolescents presented on average with mild to moderate depressive symptoms and SI at baseline (Table 1). Baseline parental listening and limit setting were within the normative range, whereas parental monitoring was in the high-risk range (Dishion et al., 2003). All family functioning variables were above the clinical cutoff except for behavior control (Epstein et al., 1983).

Predictive Effect of Baseline Family Functioning and Parenting Processes on Depressive Symptoms and Suicidal Ideation

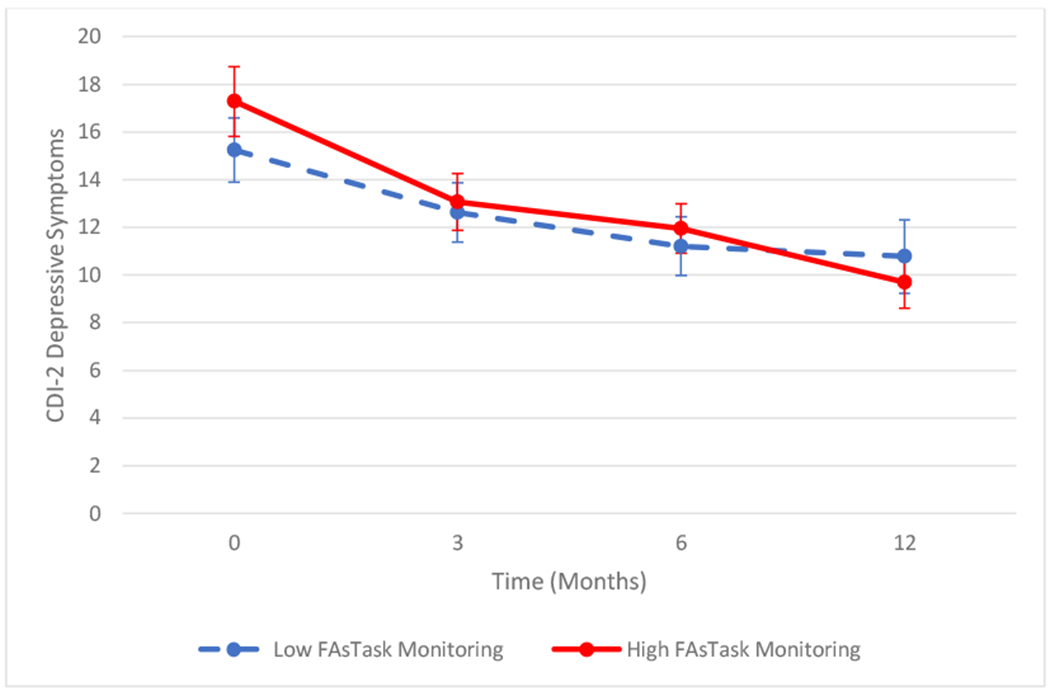

In step-up MRMs examining longitudinal depressive symptom trajectory over 12 months, covarying for baseline depressive symptoms, time and FAsTask parental monitoring emerged as significant predictors of slope; FAsTask parental monitoring was not a significant predictor of intercept (Table 3). Depressive symptoms significantly decreased over 12 months [F(267.06)=56.97, p<.001, d=1.43] and parental monitoring was predictive of depressive symptom trajectory (slope) [F(264.09)=5.30, p=.022, d=0.44]. Those with higher parental monitoring demonstrated a steeper slope/rate of improvement in depressive symptoms over one year compared to those with lower parental monitoring, whose initial improvement in depressive symptoms leveled off between 6 and 12 months (Figure 1). There were no significant associations between FAsTask parental listening or limit setting, PMQ Monitoring, or any FAD family functioning variables with depressive symptom trajectory (all ps>.05). Also, baseline SI was not a significant covariate (p>.05) and thus was removed from the final MRM.

Table 3.

Final Mixed-Effects Regression Models Examining the Predictive Effect of Baseline Parental Monitoring on Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms and Suicidal Ideation

| Depressive Symptoms |

||

|---|---|---|

| Effects | B(SE) | 95% CI |

| Intercept | 15.75(0.54)*** | 14.69, 16.80 |

| Baseline CDI-2 Depression | 0.61(0.04)*** | 0.53, 0.69 |

| Time | −1.98(0.26)*** | −2.50, −1.47 |

| FAsTask Parental Monitoring | 0.36(0.37) | −0.37, 1.08 |

| FAsTask Parental Monitoring x Time | −0.41(0.18)* | −0.76, −0.06 |

| Suicidal Ideation |

||

| Effects | B(SE) | 95% CI |

| Intercept | 14.36(0.90)*** | 12.58, 16.13 |

| Baseline SIQ Suicidal Ideation | 0.57(0.03)*** | 0.50, 0.63 |

| Time | −2.33(0.48)*** | −3.27, −1.38 |

| FAsTask Parental Monitoring | 0.56(0.62) | −0.65, 1.78 |

| FAsTask Parental Monitoring x Time | −0.79(0.32)* | −1.43, −0.15 |

Note. FAsTask= Family Assessment Task; CDI-2=Children’s Depression Inventory-2; SIQ=Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire.

p<.05;

p<.001

Figure 1.

Predictive effect of baseline parental monitoring on trajectory of depressive symptoms. Median splits dichotomized high versus low monitoring. Average depressive symptom scores are plotted over time. Error bars reflect the standard error. FAsTask= Family Assessment Task; CDI-2=Children’s Depression Inventory-2.

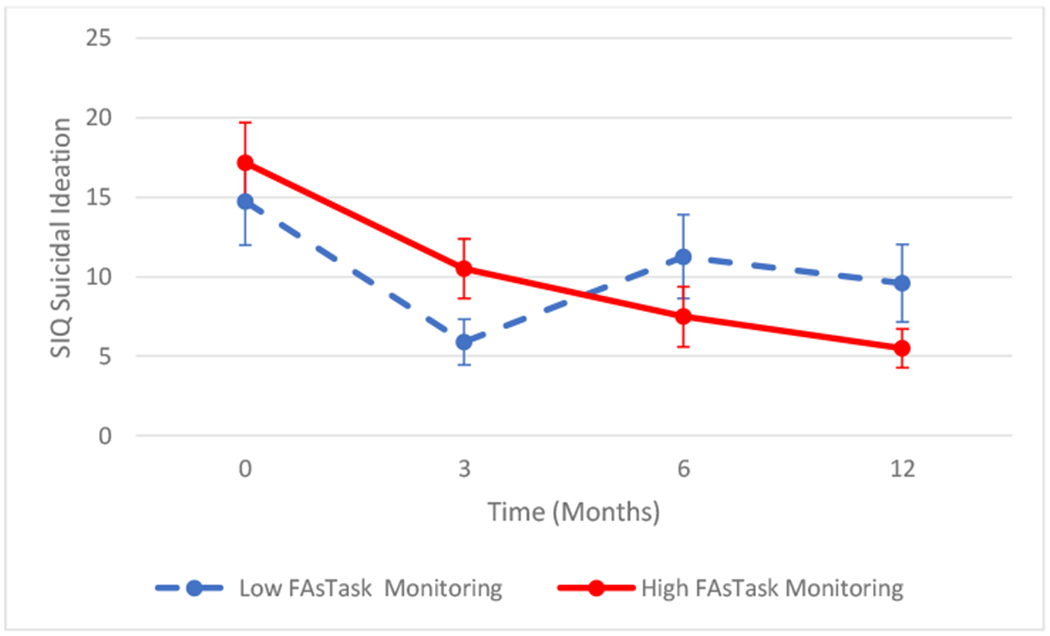

In step-up MRMs examining longitudinal SI trajectory over 12 months, covarying for baseline SI, time and FAsTask parental monitoring emerged as significant predictors of slope; FAsTask parental monitoring was not a significant predictor of intercept (Table 3). SI significantly decreased over 12 months [F(269.67)=23.60, p<.001, d=0.92] and parental monitoring was predictive of SI trajectory (slope) [F(265.79)=5.94, p=.015, d=0.46]. Those with higher parental monitoring demonstrated a decreasing SI trajectory over one year compared to those with lower parental monitoring, who showed an initial decline in SI, but then an increase starting at 3 months (Figure 2). There were no significant associations between FAsTask parental listening or limit setting, PMQ Monitoring, or any FAD family functioning variables with SI trajectory (all ps>.05). Also, baseline depression was not a significant covariate (p>.05) and thus was removed from the final MRM.

Figure 2.

Predictive effect of baseline parental monitoring on trajectory of suicidal ideation. Median splits dichotomized high versus low monitoring. Average suicidal ideation scores are plotted over time. Error bars reflect the standard error. FAsTask= Family Assessment Task; SIQ=Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire.

Change in Family Functioning and Parenting Processes Over Time

In MRMs examining longitudinal FAD family functioning and PMQ and FAsTask parenting processes over 12 months, the Treatment Group x Time interaction effect was not significant in any models (all ps>.05). Time emerged as a significant predictor of slope in two models (Table 4). Specifically, FAD Roles significantly improved over 12 months across conditions [F(97.19)=6.12, p=.015, d=0.47]. FAD Affective Involvement also significantly improved over 12 months across conditions [F(100.77)=4.20, p>=.043, d=0.39]. There were no significant longitudinal changes in FAsTask or PMQ parenting processes, nor in other FAD family functioning subscales (all ps>.05).

Table 4.

Final Mixed-Effects Regression Models Examining Trajectories of Family Functioning and Parenting Processes

| FAsTask Listening | FAsTask Limit Setting | FAsTask Monitoring | PMQ Monitoring | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effects | B(SE) | 95% CI | B(SE) | 95% CI | B(SE) | 95% CI | B(SE) | 95% CI |

| Intercept | 7.27(0.17)*** | 6.93, 7.62 | 6.10(0.21)*** | 5.68, 6.52 | 4.58(0.20)*** | 4.18, 4.97 | 30.37(1.04)*** | 28.30, 32.43 |

| Treatment Group | 0.09(0.23) | −0.37, 0.55 | 0.66(0.29)* | 0.09, 1.23 | 0.46(0.27) | −0.07, 0.99 | −0.87(1.39) | −3.63, 1.89 |

| Time | −0.06(0.09) | −0.23, 0.11 | −0.08(0.11) | −0.29, 0.13 | 0.11(0.10) | −0.08, 0.31 | −0.76(0.39) | −1.53, 0.02 |

| Treatment Group x Time | −0.10(0.11) | −0.32, 0.12 | −0.22(0.14) | −0.50, 0.06 | −0.10(0.13) | −0.36, 0.16 | 0.71(0.52) | −0.32, 1.73 |

| FAD Problem Solving | FAD Communication | FAD Roles | FAD Affective Responsiveness | |||||

| Effects | B(SE) | 95% CI | B(SE) | 95% CI | B(SE) | 95% CI | B(SE) | 95% CI |

| Intercept | 2.18(0.06)*** | 2.06, 2.29 | 2.20(0.05)*** | 2.10, 2.31 | 2.49(0.05)*** | 2.39, 2.60 | 2.09(0.07)*** | 1.97, 2.22 |

| Treatment Group | −0.07(0.08) | −0.23, 0.08 | −0.05(0.07) | −0.20, 0.09 | −0.05(0.07) | −0.19, 0.10 | −0.04(0.09) | −0.21, 0.14 |

| Time | −0.02(0.02) | −0.07, 0.02 | −0.01(0.02) | −0.05, 0.02 | −0.04(0.02)* | −0.08, −0.01 | 0.00(0.02) | −0.04, 0.05 |

| Treatment Group x Time | −0.02(0.03) | −0.08, −0.04 | −0.02(0.02) | −0.07, 0.02 | 0.04(0.02) | −0.01, 0.08 | −0.04(0.03) | −0.10, 0.02 |

| FAD Affective Involvement | FAD Behavior Control | FAD General Functioning | ||||||

| Effects | B(SE) | 95% CI | B(SE) | 95% CI | B(SE) | 95% CI | ||

| Intercept | 2.38(0.07)*** | 2.24, 2.51 | 1.89(0.06)*** | 1.78, 2.00 | 2.16(0.06)*** | 2.03, 2.28 | ||

| Treatment Group | −0.09(0.09) | −0.27, 0.09 | −0.01(0.07) | −0.15, 0.14 | −0.10(0.08) | −0.27, 0.07 | ||

| Time | −0.05(0.03)* | −0.10, −0.00 | −0.02(0.02) | −0.06, 0.02 | −0.04(0.02) | −0.08, 0.00 | ||

| Treatment Group x Time | 0.02(0.03) | −0.05, 0.08 | −0.01(0.03) | −0.06, 0.05 | 0.01(0.03) | −0.05, 0.07 | ||

Note. FAsTask= Family Assessment Task; PMQ=Parental Monitoring Questionnaire; FAD=Family Assessment Device.

p<.05;

p<.001

Discussion

This study examined whether family functioning and parenting processes predicted trajectories of depressive symptoms and SI in a sample of adolescents with comorbid SUDs and psychiatric disorders who were enrolled in a clinical trial. Across treatment conditions, depressive symptoms and SI improved over a 12-month follow-up period. The family functioning variables of family roles and affective involvement also improved over 12 months. In addition, baseline parenting processes measured via observational coding influenced course, such that higher baseline parental monitoring was predictive of improved depressive symptoms and SI. Parenting effects were found after covarying baseline depressive symptoms and SI, and were significant above and beyond the effect of time. No effects were found for family functioning or self-reported parental monitoring on depressive symptom and SI trajectories. Results suggest that family functioning variables of family roles and affective involvement may be mutable intervention targets, and observed parental monitoring may be an important prognostic indicator of depressive symptoms and SI in adolescents with co-occurring substance use and psychiatric conditions. Thus, these family and parenting factors may be important to assess and target in treatment.

The finding that parental monitoring was predictive of improvement in depressive symptoms and SI across treatment conditions adds to the literature on family predictors of treatment response for depression (Asarnow et al., 2009; Birmaher et al., 2000; Feeny et al., 2009; Gunlicks-Stoessel et al., 2010; Rohde et al., 2018) and family risk factors for SI (King and Merchant, 2008; Wagner et al., 2003). In addition, as many EBTs for depression (Weersing et al., 2017) and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors (Glenn et al., 2019) incorporate parents and families in treatment, these results underscore assessing and targeting parental monitoring. There is also evidence that parental monitoring reduces risk for depression in adolescence (Kim and Ge, 2000). Current results extend these findings to a sample of adolescents with co-occurring substance use and psychiatric conditions. Parental monitoring involves actively attending to and tracking adolescents’ whereabouts, activities, and adaptations, which can lead to improved parental knowledge (Dishion and McMahon, 1998) and possibly increased youth disclosure. These processes appear to improve depressive symptoms and SI, as well as reduce adolescent substance use.

Specifically, parental monitoring often serves to promote rule-following/compliance and socialization with appropriate peer groups, which is useful for attenuating risk for SUDs and disruptive behavior (Chilcoat and Anthony, 1996; Dishion and McMahon, 1998; Westling et al., 2008). Parental monitoring in the context of adolescent depression and SI could take a similar, but also unique, form. For instance, in addition to promoting rule-abiding behavior, parents may also monitor and reinforce adolescents’ use of coping skills (e.g., problem solving, cognitive restructuring, affect regulation, distress tolerance), engagement in pleasant and social activities, and as needed use of a safety plan (Glenn et al., 2019; Weersing et al., 2017). Thus, it follows that parental monitoring in this form may lead to improvements in depressive symptoms and SI. Specific parental monitoring behaviors were not assessed in this study, though future research should identify monitoring behaviors that may concurrently or differentially predict improvements in SUDs, depression, and SI.

Notably, significant differences in depressive symptoms and SI as related to parental monitoring did not occur until later follow-ups. Thus, while families were still involved in active treatment, or more closely discharged from active treatment (whether I-CBT or TAU), outcomes were similar across groups, presumably because individual sessions with the adolescent led to symptom reduction. However, as the length of time from end of treatment elongated, parents who employed more effective monitoring at baseline may have continued to do so over the follow-up period, leading to improvements in adolescents’ symptoms overtime.

It is also well documented that family relationships are impaired in adolescents with SUDs (Barnes and Farrell, 1992; Calafat et al., 2014; Chilcoat and Anthony, 1996; Fallu et al., 2010; Hawkins et al., 1992; Mares et al., 2011; van der Vorst et al., 2006), depression (Beardslee et al., 1998; Bodner et al., 2018; Garber, 2006; Milevsky et al., 2007; Sander and McCarty, 2005; Sheeber et al., 2007; Van Loon et al., 2014), and SI (King and Merchant, 2008; Wagner et al., 2003). Thus, parents who are more adept at monitoring and supporting adolescents in coping skills use may also have closer and more supportive relationships, which could contribute to symptom reduction. Though future research is needed to explore these possible mechanisms for improvement of symptoms, results highlight the importance of parental monitoring in improving depressive symptoms and SI in adolescents with co-occurring SUDs and psychiatric conditions. Specifically, adolescents of parents with adequate monitoring ability may fare well in psychotherapies employing parent/family skill-building, while those of parents who either underemphasize or under-employ monitoring may require adjunctive or more intensive interventions targeting parenting to achieve similar benefit

It is also notable that only parenting processes, as opposed to family functioning, predicted treatment response. The adolescent mood disorders treatment literature has primarily focused on family interaction factors as predictors of treatment outcome, whereas the adolescent substance use literature has consistently documented parenting variables as risk and protective factors (Chilcoat and Anthony, 1996; Westling et al., 2008). Current findings suggest that among adolescents with co-occurring SUDs and psychiatric conditions, parenting processes (particularity parental monitoring abilities) influence depressive symptoms and SI outcomes, as opposed to family constructs. This may be due to the complex presentation of these adolescents and families, and parenting may have a beneficial impact on SUDs, depressive symptoms, and SI through shared mechanisms (e.g., if parents engage in adequate monitoring, adolescents may be less likely to get in trouble with the law/others via substance use and/or other means, which could lead to reduced conflict in the home and by extension decreased stress, mood symptoms, and SI). Thus, for co-occurring populations parenting may be a potent first step to achieving reduction in symptoms and possibly a prerequisite to targeting dysfunctional family processes. While more research is needed to investigate optimal sequencing of therapeutic strategies, results highlight the importance of enhancing parenting capabilities in samples of adolescents with comorbid psychiatric and substance use conditions.

This study also adds to the methodological literature by using an observational coding parent-adolescent interaction task (FAsTask) to assess parenting processes. Significant effects for parental monitoring were found only when using observational coding, not for parental self-report. Limitations of existing parenting self-reports include variable psychometric properties, assessment of only certain aspects of the overall constructs (with few items and response options), and interpretations/biases by parents when completing measures (Gardner, 2000). In addition, observational techniques provide a real-time sample of parenting behaviors, as well as how these behaviors are altered by others’ reactions. However, studies utilizing observational methodologies to assess parenting processes are scarce (Dishion et al., 2004; Dishion et al., 2003). Thus, use of the observational coding FAsTask in this study offered a more comprehensive and psychometrically sound assessment of parenting processes relevant to depressive symptom and SI treatment response among adolescents with comorbid SUDs and psychiatric disorders, and may be important to incorporate in future research examining parenting.

Finally, although there were no significant differences across conditions, it is notable that the family functioning variables of family roles and affective involvement significantly improved over follow-up. As both I-CBT and TAU incorporated parent and family sessions as needed, it is possible that these were effective for improving family roles (having established behavior patterns to fulfill family functions) and affective involvement (family members’ ability to experience appropriate affect across situations). In turn, improvement in these family constructs may have contributed to improvement in adolescents’ depressive symptoms and SI, as having established roles and being able to regulate and express emotions effectively may contribute to a more supportive, stable, and validating environment, thereby facilitating improvement in adolescents’ internalizing symptoms. However, as all measures were collected concurrently and therefore directionality cannot be determined, the reverse may also be true: adolescents’ symptom improvement could have influenced and promoted a more amicable home environment, thereby facilitating improved family interactions. Of note, there were no significant changes in parenting processes overtime, even though enhanced parental monitoring predicted improved depressive symptom and SI trajectories. Thus, it is possible that in the treatment of adolescents with comorbid SUDs and psychiatric disorders, parental monitoring may be a helpful prognostic indicator of depressive symptom and SI outcomes, though family functioning may be more amenable to change than parental monitoring. Findings suggest that treatment protocols should more systematically and thoroughly address parental monitoring. Though additional research is needed to further explore these possibilities, findings clearly point to the importance of family functioning and parental monitoring in the treatment of adolescents with comorbid SUDs and psychiatric disorders.

Limitations

Although this study has several strengths, such as being conducted in a CMHC and enrolling a diverse sample of youth from challenging socioeconomic circumstances with a range of psychiatric and substance use problems, results should be interpreted within the context of limitations. First, primary outcomes documented no significant treatment group effects (I-CBT vs. TAU) for psychiatric symptoms (Wolff et al., 2020). Given this and the modest sample size, only predictive effects, as opposed to moderators of outcome, were analyzed. Second, attrition over follow-up, as in any longitudinal treatment study, may have limited power to detect additional significant effects over later time points. Third, although the heterogenous and transdiagnostic makeup of the sample is a strength in terms of generalizability of findings to practice settings, it is unclear whether associations between parental monitoring with depressive symptoms and SI would extend to a depressed sample without co-occurring SUDs. Fourth, the FAD, PMQ, and FAsTask were selected because they directly related to the family and parent training portions of I-CBT. However, other unmeasured family constructs (e.g., cohesion, adaptability) and parental psychopathology may also be important in predicting depressive symptoms and SI outcomes in this sample. Finally, the frequency, intensity, and specific types of parental monitoring were not assessed in this study, and it is likely that some monitoring styles and strategies are harmful.

Thus, future research should address shortcomings by: 1) replicating findings in diverse populations, for instance, in samples with a higher proportion of bipolar disorders as well as in samples of youth with depression without co-occurring SUDs; 2) using a larger sample to enhance power to detect additional parent- and family-based effects; 3) examining the potential moderating and mediating role of parent/family variables in explaining outcomes in I-CBT vs. TAU; 4) incorporating additional observational coding tasks to measure other parent/family constructs potentially related to treatment outcomes; and 5) evaluating the influence of different types of parental monitoring.

Conclusions

Findings add to the literature on the importance of assessing parent/family characteristics and involving parents in the treatment of adolescents with comorbid substance use and psychiatric conditions. Higher levels of parental monitoring were predictive of decreased depressive symptoms and SI. In addition, family roles and affective involvement significantly improved. Thus, parental monitoring may be important to measure at the outset of psychosocial treatment. Adolescents of parents with adequate monitoring capabilities may benefit from interventions incorporating parent/family components. However, adolescents whose parents demonstrate impairment in monitoring may require additional supports or even greater therapeutic focus on parenting skills to obtain similar benefit in depressive symptoms and SI. In addition, family roles and affective involvement may be important intervention targets for adolescents with comorbid substance use and psychiatric conditions. Thus, results indicate the need to actively and comprehensively engage parents and families when treating adolescents with co-occurring conditions, as enhancing parent, family, and adolescent skills may be important for improving depressive symptoms and SI in this high-risk population.

Highlights.

Family/parent factors were examined in youth with substance/psychiatric disorders.

Family and parenting predictors of treatment response in this RCT were analyzed.

Higher baseline parental monitoring predicted improved depression and SI over time.

Family roles and affective involvement significantly improved over time.

Parent monitoring/family factors are important in substance/psychiatric treatment.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge and thank the participants and their families for their time and effort completing this study, without which this research would not be possible.

Role of the Funding Source

This study was supported by grant number R01AA020705 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Clinical Trial Registration #: NCT01667159. The funders had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Institutional Review Board

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Lifespan Corporation and Brown University.

References

- Armstrong TD, Costello EJ, 2002. Community studies on adolescent substance use, abuse, or dependence and psychiatric comorbidity. J Consult Clin Psychol 70, 1224–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Emslie G, Clarke G, Wagner KD, Spirito A, Vitiello B, Iyengar S, Shamseddeen W, Ritz L, Birmaher B, Ryan N, Kennard B, Mayes T, DeBar L, McCracken J, Strober M, Suddath R, Leonard H, Porta G, Keller M, Brent D, 2009. Treatment of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-resistant depression in adolescents: predictors and moderators of treatment response. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 48, 330–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GM, Farrell MP, 1992. Parental support and control as predictors of adolescent drinking, delinquency, and related problem behaviors. Journal of Marriage and the Family 54, 763–776. [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee WR, Versage EM, Gladstone TR, 1998. Children of affectively ill parents: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 37, 1134–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belardinelli C, Hatch JP, Olvera RL, Fonseca M, Caetano SC, Nicoletti M, Pliszka S, Soares JC, 2008. Family environment patterns in families with bipolar children. J Affect Disord 107, 299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Brent DA, Kolko D, Baugher M, Bridge J, Holder D, Iyengar S, Ulloa RE, 2000. Clinical outcome after short-term psychotherapy for adolescents with major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57, 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodner N, Kuppens P, Allen NB, Sheeber LB, Ceulemans E, 2018. Affective family interactions and their associations with adolescent depression: A dynamic network approach. Dev Psychopathol 30, 1459–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Perper JA, Moritz G, Allman C, Friend A, Roth C, Schweers J, Balach L, Baugher M, 1993. Psychiatric risk factors for adolescent suicide: a case-control study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 32, 521–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calafat A, Garcia F, Juan M, Becona E, Fernandez-Hermida JR, 2014. Which parenting style is more protective against adolescent substance use? Evidence within the European context. Drug Alcohol Depend 138, 185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilcoat HD, Anthony JC, 1996. Impact of parent monitoring on initiation of drug use through late childhood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 35, 91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clingempeel WG, Britt SC, Henggeler SW, 2008. Beyond treatment effects: comorbid psychopathologies and long-term outcomes among substance-abusing delinquents. Am J Orthopsychiatry 78, 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DelBello MP, Hanseman D, Adler CM, Fleck DE, Strakowski SM, 2007. Twelve-month outcome of adolescents with bipolar disorder following first hospitalization for a manic or mixed episode. Am J Psychiatry 164, 582–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McMahon RJ, 1998. Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: a conceptual and empirical formulation. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 1, 61–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Nelson SE, Bullock BM, 2004. Premature adolescent autonomy: parent disengagement and deviant peer process in the amplification of problem behaviour. J Adolesc 27, 515–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Nelson SE, Kavanagh K, 2003. The family check-up with high-risk young adolescents: Preventing early-onset substance use by parent monitoring. Behavior Therapy 34, 553–571. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein NB, Baldwin LM, Bishop DS, 1983. THE McMASTER FAMILY ASSESSMENT DEVICE*. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 9, 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Fallu JS, Janosz M, Briere FN, Descheneaux A, Vitaro F, Tremblay RE, 2010. Preventing disruptive boys from becoming heavy substance users during adolescence: a longitudinal study of familial and peer-related protective factors. Addict Behav 35, 1074–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeny NC, Silva SG, Reinecke MA, McNulty S, Findling RL, Rohde P, Curry JF, Ginsburg GS, Kratochvil CJ, Pathak SM, May DE, Kennard BD, Simons AD, Wells KC, Robins M, Rosenberg D, March JS, 2009. An exploratory analysis of the impact of family functioning on treatment for depression in adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 38, 814–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Huang X, Musacchio KM, Jaroszewski AC, Chang BP, Nock MK, 2017. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol Bull 143, 187–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristad MA, MacPherson HA, 2014. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent bipolar spectrum disorders. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 43, 339–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, 2006. Depression in children and adolescents: linking risk research and prevention. Am J Prev Med 31, S104–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner F, 2000. Methodological issues in the direct observation of parent-child interaction: do observational findings reflect the natural behavior of participants? Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 3, 185–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn CR, Esposito EC, Porter AC, Robinson DJ, 2019. Evidence Base Update of Psychosocial Treatments for Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors in Youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 48, 357–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BI, Bukstein OG, 2010. Comorbid substance use disorders among youth with bipolar disorder: opportunities for early identification and prevention. J Clin Psychiatry 71, 348–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BI, Strober MA, Birmaher B, Axelson DA, Esposito-Smythers C, Goldstein TR, Leonard H, Hunt J, Gill MK, Iyengar S, Grimm C, Yang M, Ryan ND, Keller MB, 2008. Substance use disorders among adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Bipolar Disord 10, 469–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella CE, Joshi V, Hser Y-I, 2004. Effects of comorbidity on treatment processes and outcomes among adolescents in Drug Treatment Programs. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse 13, 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gunlicks-Stoessel M, Mufson L, Jekal A, Turner JB, 2010. The impact of perceived interpersonal functioning on treatment for adolescent depression: IPT-A versus treatment as usual in school-based health clinics. J Consult Clin Psychol 78, 260–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY, 1992. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin 112, 64–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh J, Curry JF, Kaminer Y, 2014. What is the impact of comorbid depression on adolescent substance abuse treatment? Subst Abus 35, 364–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Henderson CE, Becker SJ, Knight DK, 2018. Evidence Base on Outpatient Behavioral Treatments for Adolescent Substance Use, 2014-2017: Outcomes, Treatment Delivery, and Promising Horizons. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 47, 499–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N, 1997. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36, 980–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan-Miller D, Peris T, Axelson D, Kowatch RA, Miklowitz DJ, 2012. Family functioning, social impairment, and symptoms among adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 51, 1085–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Ge X, 2000. Parenting practices and adolescent depressive symptoms in Chinese American families. Journal of Family Psychology 14, 420–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CA, Ghaziuddin N, McGovern L, Brand E, Hill E, Naylor M, 1996. Predictors of comorbid alcohol and substance abuse in depressed adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 35, 743–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CA, Merchant CR, 2008. Social and interpersonal factors relating to adolescent suicidality: a review of the literature. Arch Suicide Res 12, 181–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, 2010. Children’s Depression Inventory 2nd Edition (CDI-2). Multi-Health Systems, Inc., North Tonawanda, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Clarke GN, Seeley JR, Rohde P, 1994. Major depression in community adolescents: age at onset, episode duration, and time to recurrence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 33, 809–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson HA, Algorta GP, Mendenhall AN, Fields BW, Fristad MA, 2014. Predictors and moderators in the randomized trial of multifamily psychoeducational psychotherapy for childhood mood disorders. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 43, 459–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson HA, Ruggieri AL, Christensen RE, Schettini E, Kim KL, Thomas SA, Dickstein DP, 2018. Developmental evaluation of family functioning deficits in youths and young adults with childhood-onset bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 235, 574–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mares SH, van der Vorst H, Engels RC, Lichtwarck-Aschoff A, 2011. Parental alcohol use, alcohol-related problems, and alcohol-specific attitudes, alcohol-specific communication, and adolescent excessive alcohol use and alcohol-related problems: An indirect path model. Addict Behav 36, 209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masip AF, Amador-Campos JA, Gómez-Benito J, del Barrio Gándara V, 2010. Psychometric properties of the Children’s Depression Inventory in community and clinical sample. The Spanish Journal of Psychology 13, 990–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Zhang H, Avenevoli S, Acharyya S, Neuenschwander M, Angst J, 2003. Longitudinal trajectories of depression and anxiety in a prospective community study: the Zurich Cohort Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60, 993–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, Axelson DA, George EL, Taylor DO, Schneck CD, Sullivan AE, Dickinson LM, Birmaher B, 2009. Expressed emotion moderates the effects of family-focused treatment for bipolar adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 48, 643–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milevsky A, Schlechter M, Netter S, Keehn D, 2007. Maternal and Paternal Parenting Styles in Adolescents: Associations with Self-Esteem, Depression and Life-Satisfaction. Journal of Child and Family Studies 16, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Miller IW, Epstein NB, Bishop DS, Keitner GI, 1985. THE McMASTER FAMILY ASSESSMENT DEVICE: RELIABILITY AND VALIDITY*. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 11, 345–356. [Google Scholar]

- Nader EG, Kleinman A, Gomes BC, Bruscagin C, dos Santos B, Nicoletti M, Soares JC, Lafer B, Caetano SC, 2013. Negative expressed emotion best discriminates families with bipolar disorder children. J Affect Disord 148, 418–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez Algorta G, MacPherson HA, Youngstrom EA, Belt CC, Arnold LE, Frazier TW, Taylor HG, Birmaher B, Horwitz SM, Findling RL, Fristad MA, 2018. Parenting Stress Among Caregivers of Children With Bipolar Spectrum Disorders. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 47, S306–s320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirkola T, Pelkonen M, Karlsson L, Kiviruusu O, Strandholm T, Tuisku V, Ruuttu T, Marttunen M, 2011. Differences in Characteristics and Treatment Received among Depressed Adolescent Psychiatric Outpatients with and without Co-Occuring Alcohol Misuse: A 1-Year Follow-Up Study. Depress Res Treat 2011, 140868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM, Mazza JJ, 1999. Assessment of suicidal ideation in inner-city children and young adolescents: Reliability and validity of the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-JR. School Psychology Review 28, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Clarke GN, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Kaufman NK, 2001. Impact of comorbidity on a cognitive-behavioral group treatment for adolescent depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40, 795–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Turner CW, Waldron HB, Brody JL, Jorgensen J, 2018. Depression Change Profiles in Adolescents Treated for Comorbid Depression/Substance Abuse and Profile Membership Predictors. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 47, 595–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe CL, Liddle HA, Greenbaum PE, Henderson CE, 2004. Impact of psychiatric comorbidity on treatment of adolescent drug abusers. J Subst Abuse Treat 26, 129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander JB, McCarty CA, 2005. Youth depression in the family context: familial risk factors and models of treatment. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 8, 203–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkel LS, West AE, Harral EM, Patel NB, Pavuluri MN, 2008. Parent-child interactions in pediatric bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychol 64, 422–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shane PA, Jasiukaitis P, Green RS, 2003. Treatment outcomes among adolescents with substance abuse problems: The relationship between comorbidities and post-treatment substance involvement. Evaluation and Program Planning 26, 393–402. [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber LB, Davis B, Leve C, Hops H, Tildesley E, 2007. Adolescents’ relationships with their mothers and fathers: associations with depressive disorder and subdiagnostic symptomatology. J Abnorm Psychol 116, 144–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB, 2003. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford University Press, New York, NY, US. [Google Scholar]

- Stattin H, Kerr M, 2000. Parental monitoring: a reinterpretation. Child Dev 71, 1072–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan AE, Judd CM, Axelson DA, Miklowitz DJ, 2012. Family functioning and the course of adolescent bipolar disorder. Behav Ther 43, 837–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swendsen JD, Merikangas KR, Canino GJ, Kessler RC, Rubio-Stipec M, Angst J, 1998. The comorbidity of alcoholism with anxiety and depressive disorders in four geographic communities. Compr Psychiatry 39, 176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson KL, Brown SA, Abrantes A, 2004. Psychiatric comorbidity and substance use treatment outcomes of adolescents. Psychol Addict Behav 18, 160–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Vorst H, Engels RC, Meeus W, Dekovic M, 2006. Parental attachment, parental control, and early development of alcohol use: a longitudinal study. Psychol Addict Behav 20, 107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Loon LMA, Van de Ven MOM, Van Doesum KTM, Witteman CLM, Hosman CMH, 2014. The Relation Between Parental Mental Illness and Adolescent Mental Health: The Role of Family Factors. Journal of Child and Family Studies 23, 1201–1214. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner BM, Cole RE, Schwartzman P, 1996. Comorbidity of symptoms among junior and senior high school suicide attempters. Suicide Life Threat Behav 26, 300–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner BM, Silverman MAC, Martin CE, 2003. Family factors in youth suicidal behaviors. Sage Publications, pp. 1171–1191. [Google Scholar]

- Weersing VR, Jeffreys M, Do MT, Schwartz KT, Bolano C, 2017. Evidence Base Update of Psychosocial Treatments for Child and Adolescent Depression. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 46, 11–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein SM, Henry DB, Katz AC, Peters AT, West AE, 2015. Treatment moderators of child- and family-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for pediatric bipolar disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 54, 116–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westling E, Andrews JA, Hampson SE, Peterson M, 2008. Pubertal timing and substance use: the effects of gender, parental monitoring and deviant peers. J Adolesc Health 42, 555–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, Martelon M, Kruesi MJ, Parcell T, Westerberg D, Schillinger M, Gignac M, Biederman J, 2009. Does conduct disorder mediate the development of substance use disorders in adolescents with bipolar disorder? A case-control family study. J Clin Psychiatry 70, 259–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff J, Esposito-Smythers C, Frazier E, Stout R, Gomez J, Massing-Schaffer M, Nestor B, Cheek S, Graves H, Yen S, Hunt J, Spirito A, 2020. A randomized trial of an integrated cognitive behavioral treatment protocol for adolescents receiving home-based services for co-occurring disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat 116, 108055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngstrom EA, Youngstrom JK, Freeman AJ, De Los Reyes A, Feeny NC, Findling RL, 2011. Informants are not all equal: predictors and correlates of clinician judgments about caregiver and youth credibility. Journal of child and adolescent psychopharmacology 21, 407–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]