Key Points

Question

Does immunotherapy with blinatumomab result in longer disease-free survival compared with chemotherapy as postreinduction consolidation therapy prior to hematopoietic stem cell transplant in children, adolescents, and young adults with high- and intermediate-risk first relapse of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 208 patients with high- and intermediate-risk first relapse of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and was terminated early, treatment with blinatumomab vs chemotherapy resulted in 2-year disease-free survival of 54% vs 39% of participants, but the difference was not statistically significant.

Meaning

Postreinduction treatment with blinatumomab compared with chemotherapy, followed by hematopoietic stem cell transplant, did not result in a statistically significant difference in disease-free survival, but study interpretation is limited by early termination with possible underpowering for the primary end point.

Abstract

Importance

Standard chemotherapy for first relapse of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) in children, adolescents, and young adults is associated with high rates of severe toxicities, subsequent relapse, and death, especially for patients with early relapse (high risk) or late relapse with residual disease after reinduction chemotherapy (intermediate risk). Blinatumomab, a bispecific CD3 to CD19 T cell–engaging antibody construct, is efficacious in relapsed/refractory B-ALL and has a favorable toxicity profile.

Objective

To determine whether substituting blinatumomab for intensive chemotherapy in consolidation therapy would improve survival in children, adolescents, and young adults with high- and intermediate-risk first relapse of B-ALL.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This trial was a randomized phase 3 clinical trial conducted by the Children’s Oncology Group at 155 hospitals in the US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand with enrollment from December 2014 to September 2019 and follow-up until September 30, 2020. Eligible patients included those aged 1 to 30 years with B-ALL first relapse, excluding those with Down syndrome, Philadelphia chromosome–positive ALL, prior hematopoietic stem cell transplant, or prior blinatumomab treatment (n = 669).

Interventions

All patients received a 4-week reinduction chemotherapy course, followed by randomized assignment to receive 2 cycles of blinatumomab (n = 105) or 2 cycles of multiagent chemotherapy (n = 103), each followed by transplant.

Main Outcome and Measures

The primary end point was disease-free survival and the secondary end point was overall survival, both from the time of randomization. The threshold for statistical significance was set at a 1-sided P <.025.

Results

Among 208 randomized patients (median age, 9 years; 97 [47%] females), 118 (57%) completed the randomized therapy. Randomization was terminated at the recommendation of the data and safety monitoring committee without meeting stopping rules for efficacy or futility; at that point, 80 of 131 planned events occurred. With 2.9 years of median follow-up, 2-year disease-free survival was 54.4% for the blinatumomab group vs 39.0% for the chemotherapy group (hazard ratio for disease progression or mortality, 0.70 [95% CI, 0.47-1.03]); 1-sided P = .03). Two-year overall survival was 71.3% for the blinatumomab group vs 58.4% for the chemotherapy group (hazard ratio for mortality, 0.62 [95% CI, 0.39-0.98]; 1-sided P = .02). Rates of notable serious adverse events included infection (15%), febrile neutropenia (5%), sepsis (2%), and mucositis (1%) for the blinatumomab group and infection (65%), febrile neutropenia (58%), sepsis (27%), and mucositis (28%) for the chemotherapy group.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among children, adolescents, and young adults with high- and intermediate-risk first relapse of B-ALL, postreinduction treatment with blinatumomab compared with chemotherapy, followed by transplant, did not result in a statistically significant difference in disease-free survival. However, study interpretation is limited by early termination with possible underpowering for the primary end point.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02101853

This randomized trial compares the effects of postreinduction therapy consolidation using blinatumomab, an antibody construct that links CD3+ T cells to CD19+ leukemia cells, vs chemotherapy on disease-free survival among children, adolescents, and young adults with first relapse of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Introduction

Survival for children, adolescents, and young adults with first relapse of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) is poor, especially in patients with early relapse, for whom 5-year survival is 25% to 50%.1,2,3,4,5 Standard first relapse treatment includes 4 weeks of reinduction chemotherapy followed by consolidation therapy, which includes 2 cycles of intensive multiagent chemotherapy for early bone marrow relapse (<36 months after diagnosis), followed by hematopoietic stem cell transplant.6 Many patients with early relapse cannot proceed to transplant due to adverse chemotherapy events, including serious infection,7 or inability to achieve the minimal residual disease (MRD)–negative second remission associated with optimal transplant outcomes.8,9 For late first bone marrow relapse (≥36 months after diagnosis), MRD greater than or equal to 0.1% after reinduction is associated with poor survival of approximately 50% to 60%,10,11 and consolidation therapy consists of intensive chemotherapy and transplant. Patients with late first marrow relapse and MRD less than 0.1% following reinduction have excellent survival with chemotherapy without transplant.10,11,12

Blinatumomab is a bispecific T cell–engaging antibody construct that links CD3+ T cells to CD19+ leukemia cells, inducing a cytotoxic immune response. Blinatumomab is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of adults and children with relapsed/refractory B-ALL,13,14 and received accelerated approval for MRD-positive B-ALL,15 which is conditional on confirmatory trials. This trial (AALL1331) is one of the confirmatory trials and was designed to determine whether substituting blinatumomab for chemotherapy consolidation after 1 cycle of standard reinduction chemotherapy improved disease-free survival in first relapse of B-ALL in children, adolescents, and young adults.

Methods

Trial Oversight

The trial protocol and amendments (eAppendix in Supplement 1) were approved by the National Cancer Institute Pediatric Central Institutional Review Board and by each trial center’s institutional review board. All patients or a parent/guardian provided written informed consent, which included information regarding evolving US Food and Drug Administration approval of blinatumomab. The independent Children’s Oncology Group data and safety monitoring committee met regularly to review trial safety and efficacy data according to its charter and standard operating procedures.

Eligibility and Reinduction

Patients aged 1 to 30 years with B-ALL first relapse were eligible. Exclusions included Down syndrome, Philadelphia chromosome–positive ALL, previous transplant, and previous blinatumomab treatment. All patients received 4 weeks of reinduction chemotherapy with vincristine, dexamethasone, pegasparagase, mitoxantrone, and risk-based intrathecal chemotherapy (eTable 1 in Supplement 2), which is the regimen used in the mitoxantrone-treated group in the UKALLR3 clinical trial.4

Postreinduction Evaluation and Risk Assignment

After reinduction, bone marrow aspiration was evaluated locally for morphologic response and centrally for flow cytometric MRD response (Borowitz laboratory at Johns Hopkins Hospital; sensitivity, 1 in 10 000).16 Evaluations for patients with central nervous system (CNS) or testicular extramedullary disease included lumbar puncture or testicular examination with biopsy if examination findings were equivocal. Postinduction risk groups were defined as follows: early treatment failure, defined as greater than 25% marrow blasts or failure to clear CNS leukemia; high risk, bone marrow (includes isolated bone marrow and combined bone marrow and extramedullary) relapse less than 36 months after diagnosis or isolated extramedullary relapse less than 18 months after diagnosis; intermediate risk, bone marrow relapse at least 36 months after diagnosis or isolated extramedullary relapse at least 18 months after diagnosis and MRD greater than or equal to 0.1%; and low risk, bone marrow relapse at least 36 months after diagnosis or isolated extramedullary relapse at least 18 months after diagnosis and MRD less than 0.1%.

Because previous studies have shown similar survival in these populations, patients with high- and intermediate-risk relapse were grouped together for randomization.10,11 The early treatment failure group was offered nonrandomized salvage therapy with blinatumomab. Herein are results for the high- and intermediate-risk group and for the early treatment failure group. Results for the randomized low-risk group have not yet been released by the data and safety monitoring committee.

Randomization

Following reinduction, individuals in the high- and intermediate-risk group were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive blinatumomab (experimental) or chemotherapy (control). To balance potential confounding factors, randomization was stratified by risk group (high vs intermediate risk), among the high risk group by site of relapse (bone marrow vs isolated extramedullary), and among the high-risk bone marrow relapse group by time from original diagnosis to relapse (<18 vs 18-36 months) and postreinduction MRD (<0.1% vs ≥0.1%).

Treatments and Evaluations

The blinatumomab group underwent 2 continuous 28-day infusion cycles of blinatumomab, 15 µg/m2 per day, separated by a 7-day break (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). The chemotherapy group underwent 2 chemotherapy cycles (4-week cycles), based on the UKALLR3 trial4 (eTable 3 in Supplement 2). Risk-adapted intrathecal therapy was provided to both groups. Response evaluation occurred following completion of each of the 2 cycles of randomized therapy. For flow MRD, the central laboratory was blinded to the treatment group. The MRD assay included a standard panel with CD19 and an additional CD19-independent panel.17 On completion of randomized therapy, patients underwent transplant. Transplant recommendations and procedures are described in the protocol (eAppendix in the Supplement 1).

The early treatment failure group was not eligible for randomization, but was eligible to receive up to 2 cycles of blinatumomab salvage therapy (eTable 4 in Supplement 2) unless they had residual CNS leukemia after reinduction.

Outcomes

The primary end point was disease-free survival, defined as time from randomization to late treatment failure (≥5% marrow blasts after first course of randomized therapy), relapse, second malignancy, or death. Patients without events were censored at their last follow-up date. The secondary end point was overall survival (time from randomization to death from any cause). An exploratory end point was rate of MRD negativity (<0.01%) after each course of randomized therapy. A post hoc end point was rate of proceeding to transplant. Adverse events (AEs) were graded based on the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.0), and grade 3 AEs or higher were categorized as severe. Select blinatumomab-related AEs were monitored in blinatumomab cycles 1 and 2, including cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity-related AEs, which were subclassified into seizures and encephalopathic AEs, such as cognitive disturbance, tremor, ataxia, or dysarthria.

For patients with early treatment failure who received salvage blinatumomab therapy, an exploratory end point was to estimate the rates of complete remission (<5% marrow blasts), MRD negativity (<0.01%), and proceeding to transplant in remission after salvage blinatumomab.

Race/Ethnicity

To comply with National Institutes of Health requirements, self-declared race/ethnicity data were collected by the researcher at each enrolling site, who chose from predefined categories for race (American Indian/Alaskan Native; Asian, Native Hawaiian, or other Pacific Islander; Black or African American; White; more than 1 race; and unknown or not reported) and ethnicity (not Hispanic or Latino, Hispanic or Latino, and unknown/not reported).

Statistical Analysis

The expected 2-year disease-free survival for patients with high- and intermediate-risk relapse who received the control treatment was 45%. Consistent with previous Children’s Oncology Group ALL trials,18,19 an approximate 40% reduction in events was considered to be clinically meaningful. Thus, AALL1331 was designed to detect an improvement to 63% disease-free survival (hazard ratio, 0.58) with 85% power and 1-sided α level of .025 with 110 patients per randomized group, with 2 interim analyses and 1 final analysis. One-sided testing was used because it facilitated efficient futility monitoring. The analysis set was defined as all patients randomized prior to June 30, 2019. Follow-up was current as of September 30, 2020. Patients with missing outcome data were censored at the time of last follow-up (Figure 1). Efficacy stopping boundaries were based on the O’Brien-Fleming spending function.20,21 Futility boundaries were based on testing the alternative hypothesis at the .024 level.22 AEs were assessed in the as-treated population (randomized patients who received ≥1 dose of the randomized therapy).

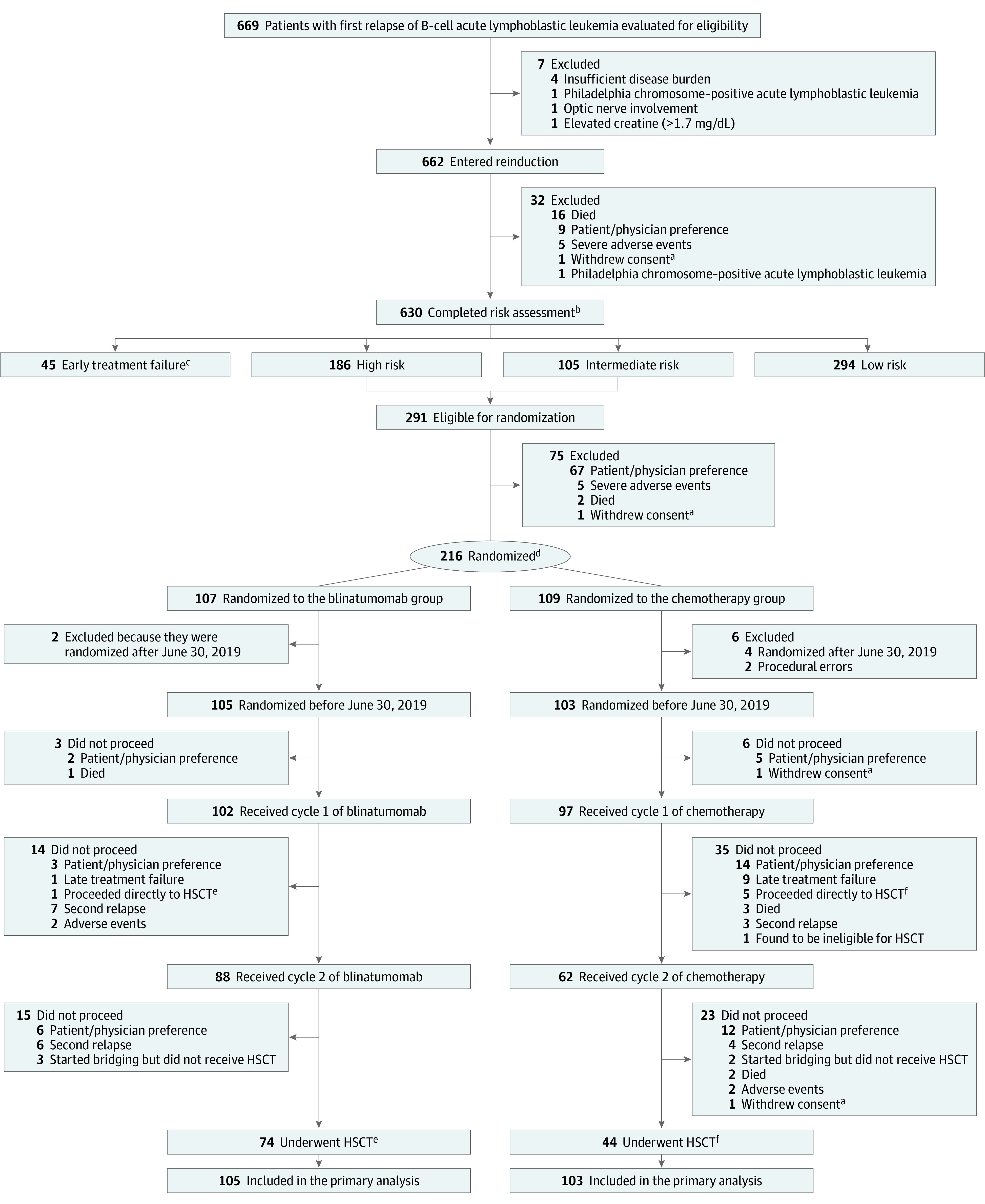

Figure 1. Flow of Patients in a Study of the Effect of Postreinduction Consolidation With Blinatumomab vs Chemotherapy .

Patients for whom protocol-specified therapy was stopped for nonevents continued to be followed up for events in the primary analysis.

aPatients were censored at the time of withdrawal of consent in the analyses.

bEarly treatment failure: >25% marrow blasts or failure to clear central nervous system leukemia; high risk, bone marrow relapse <36 mo or isolated extramedullary relapse <18 mo after diagnosis; intermediate risk, bone marrow relapse ≥36 mo or isolated extramedullary relapse ≥18 mo after diagnosis and minimal residual disease (MRD) ≥0.1%; and low risk, same as intermediate except MRD <0.1%.

cTwenty-two given blinatumomab and included in an exploratory analysis.

dIn a 1:1 ratio stratified by risk group, site of relapse, first remission duration, and postreinduction MRD.

eOne proceeded to hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) after cycle 1.

fFive patients proceeded to HSCT after cycle 1.

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate disease-free survival and overall survival rates, with standard errors assessed with the Greenwood method.23 A 1-sided stratified log-rank test was used to compare disease-free survival and overall survival between randomized groups, with a significance threshold of 1-sided P = .025. Hazard ratios and associated 95% CIs were calculated using stratified Cox proportional hazards models. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using graphical diagnostics and verified based on scaled Schoenfeld residuals.24 Comparisons of categorical variables were performed with Pearson χ2 tests or Fisher exact tests as appropriate, with a significance threshold of 2-sided P = .05. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, findings for analyses of secondary end points should be interpreted as exploratory. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata, version 15.1 (StataCorp).

Results

Early Closure of Randomization

Randomization commenced in January 2015. Following a planned interim analysis in September 2019 using a data cut-off of June 30, 2019, when 80 of 131 (61%) anticipated events occurred, the data and safety monitoring committee recommended the randomization be halted early. The P value for disease-free survival at this time was P = .06. The critical P value for the efficacy stopping rule was P = .004. Although the disease-free survival efficacy stopping rule was not met, the combination of higher disease-free survival and overall survival, lower rates of serious toxicity, and higher rates of MRD clearance for blinatumomab relative to chemotherapy prompted the data and safety monitoring committee to recommend closure of the high- and intermediate-risk randomization due to loss of clinical equipoise between the randomized treatments.

Patients and Treatment

A total of 214 patients (of a planned 220 patients) were randomized (107 to each group; Figure 1); 6 patients randomized after June 30, 2019, (2 in the blinatumomab group and 4 in the chemotherapy group) were excluded from analyses because their postrandomization therapy was affected by early randomization closure and crossover of patients in the chemotherapy group to receive blinatumomab. Thus, the final analysis included 208 randomized patients (105 in the blinatumomab group and 103 in the chemotherapy group). The groups were well-balanced in terms of baseline characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Participants in a Study of the Effect of Postreinduction Consolidation With Blinatumomab vs Chemotherapy in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults With First Relapse of B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Blinatumomab (n = 105) | Chemotherapy (n = 103) | |

| Age at enrollment, y | ||

| Median (IQR) | 9 (6-16) | 9 (5-16) |

| 1-9 | 55 (52.4) | 55 (53.4) |

| 10-12 | 10 (9.5) | 11 (10.7) |

| 13-17 | 25 (23.8) | 19 (18.4) |

| 18-20 | 8 (7.6) | 10 (9.7) |

| 21-27a | 7 (6.7) | 8 (7.8) |

| Age at initial diagnosis, y | ||

| Median (IQR) | 6 (3-13) | 6 (3-13) |

| <1 | 7 (6.7) | 10 (9.7) |

| 1-9 | 56 (53.3) | 55 (53.4) |

| 10-12 | 16 (15.2) | 11 (10.7) |

| 13-17 | 24 (22.9) | 18 (17.5) |

| 18-26a | 2 (1.9) | 9 (8.7) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 48 (45.7) | 49 (47.6) |

| Male | 57 (54.3) | 54 (52.4) |

| Race | n = 83 | n = 89 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 (2.4) | 0 |

| Asian | 4 (4.8) | 4 (4.5) |

| Black or African American | 7 (8.4) | 18 (20.2) |

| White | 69 (83.1) | 66 (74.2) |

| Multiple | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.1) |

| Ethnicity | n = 97 | n = 98 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 36 (37.1) | 34 (34.7) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 61 (62.9) | 64 (65.3) |

| Site of relapse | ||

| Marrow (≥36 mo after diagnosis) | 36 (34.3) | 34 (33.0) |

| Marrow (18-36 mo after diagnosis) | 41 (39.0) | 41 (39.8) |

| MRD ≥0.1%, No.b | 19 | 19 |

| MRD <0.1%, No.b | 22 | 21 |

| MRD unknown, No.b | 0 | 1c |

| Marrow (<18 mo after diagnosis) | 18 (17.1) | 18 (17.5) |

| MRD ≥0.1%, No.b | 8 | 8 |

| MRD <0.1%, No.b | 9 | 10 |

| MRD unknown, No.b | 1d | 0 |

| Isolated extramedullary (<18 mo after diagnosis) | 10 (9.5) | 10 (9.7) |

| Risk group assignment after reinduction | ||

| High risk | 69 (65.7) | 69 (67.0) |

| Intermediate risk | 36 (34.3) | 34 (33.0) |

| Cytogenetic groupe | ||

| Favorable | 21 (23.3) | 16 (17.6) |

| ETV6-RUNX1, No. | 12 | 8 |

| Hyperdiploid with +4, +10, No. | 9 | 8 |

| Unfavorable | 7 (7.8) | 10 (11) |

| KMT2A-rearranged, No. | 7 | 9 |

| Hypodiploid, No. | 0 | 1 |

| Other | 62 (68.9) | 65 (71.4) |

| Unknown, No. | 15 | 12 |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Patients aged up to 30 years were eligible for inclusion; however, no patient enrolled was older than 26 years at initial diagnosis or 27 years at enrollment.

Minimal residual disease (MRD) is ascertained by assays of blood specimens that use polymerase chain reactions or flow cytometry to detect acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells; MRD is defined by the presence of at least 0.01% acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells in a posttreatment blood specimen and predicts the likelihood of relapse.

This patient’s MRD after reinduction was unsatisfactory. The patient was treated as stratum “high-risk patients (marrow ≥18 to <36 mo; MRD <0.1%)” for randomization.

This patient’s MRD after reinduction was indeterminate due to a strange immunophenotype. The patient was categorized in the high-risk group for randomization.

Reported by site using indicated categorical choices, which included the “unknown” category, based on cytogenetic results from original diagnosis. The indicated cytogenetic categories were of interest due to their known association with either favorable or unfavorable prognosis in the setting of upfront treatment.

Primary End Point: Disease-Free Survival

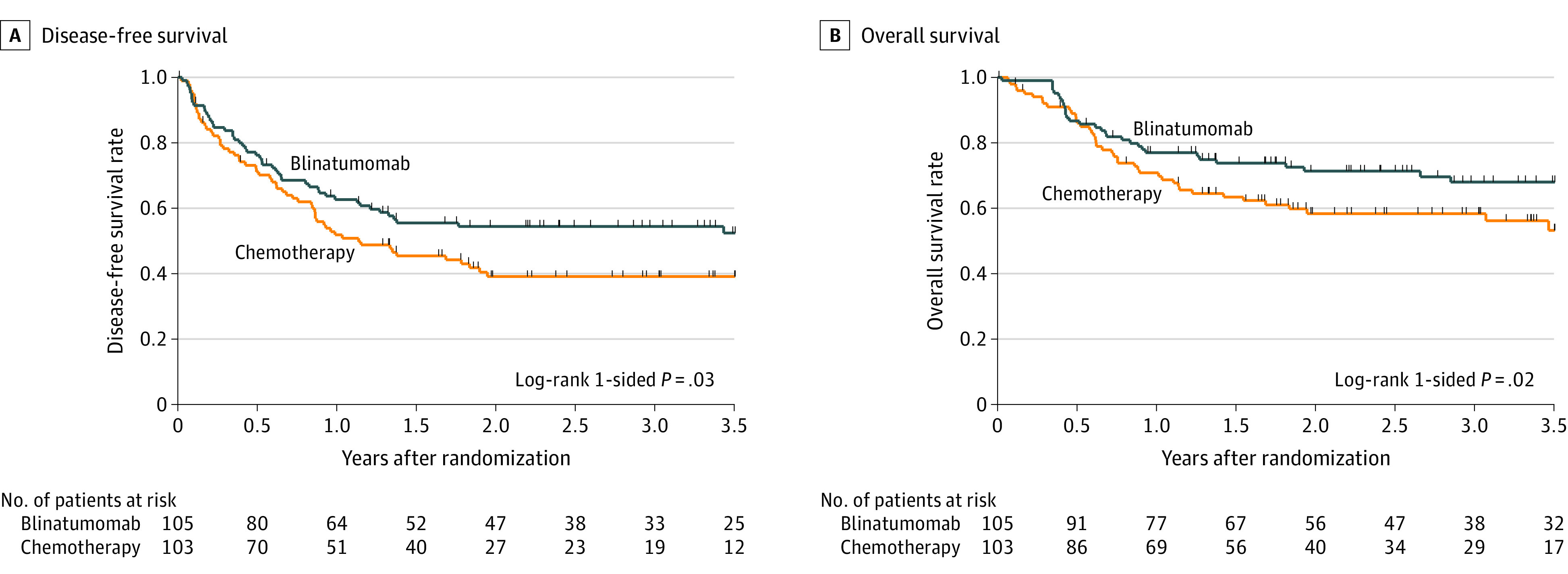

As of September 30, 2020, the median follow-up among living patients was 2.9 years (range, 0-5.6 years; interquartile range, 1.8-3.9 years) and the 2-year disease-free survival rate was 54.4% for the blinatumomab group vs 39.0% for the chemotherapy group (hazard ratio for disease progression or mortality, 0.70 [95% CI, 0.47-1.03]) (Figure 2A). This difference was not statistically significant (1-sided P = .03). First disease-free survival events are shown in Table 2. All first disease-free survival events occurred within 2 years of randomization with 1 exception (1 patient in the blinatumomab group relapsed in month 41), with median time to event of 6 months (range, 8 days to 41 months; interquartile range, 2.2-10.7 months) and no significant differences in event timing between the groups. Of the 208 randomized patients, 6 (3%) withdrew consent or were lost to follow-up with less than 2 years of follow-up.

Figure 2. Disease-Free and Overall Survival in a Study of the Effect of Postreinduction Consolidation With Blinatumomab vs Chemotherapy on Disease-Free Survival in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults With First Relapse of B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia.

The median (interquartile range) length of follow-up among living patients was 2.9 (1.8-3.9) years for all patients, 3.1 (1.8-3.9) years for the blinatumomab group, and 2.7 (1.7-3.6) years for the chemotherapy group. A, Two-year disease-free survival was 54.4% for the blinatumomab group vs 39.0% for the chemotherapy group (hazard ratio for disease progression or mortality, 0.70 [95% CI, 0.47-1.03]). B, Two-year overall survival was 71.3% for the blinatumomab group vs 58.4% for the chemotherapy group (hazard ratio for mortality, 0.62 [95% CI, 0.39-0.98]). Tic marks indicate censoring.

Table 2. Outcomes in a Study of the Effect of Postreinduction Consolidation With Blinatumomab vs Chemotherapy in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults With First Relapse of B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia.

| End point | No. (%) | Absolute difference (95% CI), % | Odds ratio (95% CI)a | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blinatumomab (n = 105) | Chemotherapy (n = 103) | ||||

| First event (components of the primary end point)b | |||||

| Late treatment failurec | 1 (1) | 9 (9) | −8 (−14 to −2) | ||

| Relapse | 35 (33) | 32 (31) | 2 (−10 to 15) | ||

| Death | 12 (11) | 18 (17) | −6 (−16 to 3) | ||

| Exploratory end pointsd | |||||

| Negative MRD at the end of reinduction | 26 (25) | 31 (30) | −5 (−17 to 7) | 0.76 (0.4 to 1.5)e | .39 |

| Negative MRD at the end of cycle 1 | 79 (75) | 33 (32) | 43 (31 to 55) | 6.4 (3.4 to 12.4)e | <.001 |

| Negative MRD at the end of cycle 2 | 69 (66) | 33 (32) | 34 (21 to 46) | 4.1(2.2 to 7.6)e | <.001 |

| Underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplantf | 74 (70) | 44 (43) | 27 (15 to 41) | 3.2 (1.7 to 5.9) | <.001 |

Odds ratios and P values are not shown for the comparisons of event rates because these are competing events.

All events but 1 took place within 2 years of randomization.

Late treatment failure was defined as ≥5% blasts in marrow after cycle 1.

Minimal residual disease (MRD) is ascertained by assays of blood specimens that use polymerase chain reactions or flow cytometry to detect acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells; MRD is defined by the presence of at least 0.01% acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells in a posttreatment blood specimen and predicts the likelihood of relapse. Negative MRD is defined as MRD less than 0.01%.

The odds ratio for negative MRD represents the odds of negative MRD in the blinatumomab group vs the chemotherapy group. In this analysis, positive MRD (defined as MRD ≥0.01% or MRD <0.1% with sensitivity of 1 in 1000) or no MRD data are considered as not having negative MRD. The rationale for including patients with no MRD data in this analysis is that the lack of MRD data was due to death, relapse, or removal from protocol therapy because of an adverse event or other poor response to therapy, so it is appropriate to include them as the converse of the optimal outcome of being able to submit a sample and have negative MRD.

Received transplant without intervening nonprotocol therapy.

Secondary End Point: Overall Survival

The 2-year overall survival rate was 71.3% for the blinatumomab group vs 58.4% for the chemotherapy group (hazard ratio for mortality, 0.62 [95% CI, 0.39-0.98]) (Figure 2B). This difference was statistically significant (1-sided P = .02). All deaths occurred within 2 years, with 5 exceptions (3 patients in the blinatumomab group died in months 31, 34, and 45 and 2 patients in the chemotherapy group died in months 36 and 41, all following earlier relapse).

Exploratory End Point: MRD

The percentages of patients who had detectable MRD prior to and after each cycle of postrandomization therapy are shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences between groups at the time of randomization (P = .39). After the first cycle of randomized therapy, the MRD negativity rate was 75% for the blinatumomab group vs 32% for the chemotherapy group (difference, 43% [95% CI, 31%-55%]; P < .001). The significant difference in MRD negativity persisted following the second cycle of randomized therapy (66% in the blinatumomab group vs 32% in the chemotherapy group; difference, 34% [95% CI, 21%-46%]; P < .001). Compared with the blinatumomab group, the chemotherapy group had more patients with no MRD data (primarily due to death, relapse, or severe AEs). For the blinatumomab group, the MRD negativity percentage dropped between the first (75%) and second (66%) cycles. Of the 15 patients who did not have negative MRD after the first cycle of blinatumomab, 5 (33%) had negative MRD after the second cycle (eTable 5 in Supplement 2). However, of the 79 patients that had negative MRD after the first blinatumomab cycle, 8 (10%) reverted to being MRD-positive and 2 (3%) relapsed after cycle 2 (eTable 6 in Supplement 2). All 10 of these patients had high-risk bone marrow relapse. Of the 8 cases of MRD re-emergence following the second cycle of blinatumomab, 7 were assessable for CD19 expression by flow cytometry and 1 had too few residual cells for characterization. Of these, 3 were CD19-negative (antigen loss) and 4 were CD19-positive. Of the 2 relapses, 1 was CD19-negative and 1 was CD19-positive.

Post Hoc End Point: Proceeding to Transplant

The percentages of patients in each randomized group who began postrandomization therapy and successfully proceeded to transplant without receiving nonprotocol therapy are shown in Table 2. For the blinatumomab group, 70% proceeded to transplant, compared with 43% for the chemotherapy group (difference, 27% [95% CI, 15%-41%]; P < .001).

AE End Point

The rates of AEs for the randomized groups are summarized in Table 3, which displays toxicities for each randomized cycle, and in eTable 7 in Supplement 2, which displays cumulative rates for both randomized cycles. The grade 3 and higher AEs with cumulative rates higher than 25% for the blinatumomab group (eTable 7 in Supplement 2) included cytopenias (neutrophils [47%], lymphocytes [40%], and white blood cells [34%]). The grade 3 and higher AEs with cumulative rates higher than 25% for the chemotherapy group (eTable 7 in Supplement 2) included cytopenias (platelets [67%], neutrophils [64%], anemia [62%], white blood cells [61%], and lymphocytes [34%]), febrile neutropenia (58%), increased alanine aminotransferase (41%), mucositis (28%), and sepsis (27%).

Table 3. Adverse Events in a Study of the Effect of Postreinduction Consolidation With Blinatumomab vs Chemotherapy in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults With First Relapse of B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia.

| Adverse event | No. (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle 1 | Cycle 2 | |||||||

| Blinatumomab (n = 102) | Chemotherapy (n = 97) | Blinatumomab (n = 88) | Chemotherapy (n = 62) | |||||

| Any grade | Grade ≥3a | Any grade | Grade ≥3a | Any grade | Grade ≥3a | Any grade | Grade ≥3a | |

| Patients with any adverse event | 99 (97) | 77 (76) | 89 (92) | 88 (91) | 81 (92) | 49 (56) | 55 (89) | 52 (84) |

| Anemia | 77 (76) | 15 (15) | 63 (65) | 51 (53) | 39 (44) | 4 (5) | 36 (58) | 35 (57) |

| White blood cell decreased | 67 (66) | 25 (25) | 59 (61) | 55 (57) | 50 (57) | 13 (15) | 30 (48) | 30 (48) |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 65 (64) | 12 (12) | 62 (64) | 38 (39) | 37 (42) | 6 (7) | 27 (44) | 8 (13) |

| Fever | 54 (53) | 6 (6) | 24 (25) | 5 (5) | 20 (23) | 2 (2) | 20 (32) | 6 (10) |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 51 (50) | 34 (33) | 58 (60) | 57 (59) | 43 (49) | 25 (28) | 32 (52) | 31 (50) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 49 (48) | 9 (9) | 51 (53) | 14 (14) | 26 (30) | 1 (1) | 24 (39) | 3 (5) |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 47 (46) | 0 | 43 (44) | 6 (6) | 18 (21) | 0 | 23 (37) | 1 (2) |

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 43 (42) | 37 (36) | 32 (33) | 30 (31) | 33 (38) | 18 (21) | 16 (26) | 15 (24) |

| Platelet count decreased | 43 (42) | 8 (8) | 63 (65) | 56 (58) | 18 (21) | 3 (3) | 37 (60) | 34 (55) |

| Hyperglycemia | 32 (31) | 2 (2) | 24 (25) | 6 (6) | 31 (35) | 2 (2) | 19 (31) | 8 (13) |

| Hypocalcemia | 31 (30) | 2 (2) | 36 (37) | 6 (6) | 12 (14) | 0 | 18 (29) | 0 |

| Hypokalemia | 28 (28) | 7 (7) | 36 (37) | 19 (20) | 21 (24) | 2 (2) | 28 (45) | 14 (23) |

| Hypophosphatemia | 18 (18) | 0 | 18 (19) | 5 (5) | 8 (9) | 0 | 7 (11) | 2 (3) |

| Hypotension | 16 (16) | 1 (1) | 11 (11) | 7 (7) | 12 (14) | 3 (3) | 7 (11) | 4 (7) |

| Blood bilirubin increased | 15 (15) | 2 (2) | 31 (32) | 7 (7) | 4 (5) | 0 | 16 (26) | 2 (3) |

| Infectionb,c | 15 (15) | 10 (10) | 48 (49) | 39 (40) | 20 (23) | 9 (10) | 42 (68) | 38 (61) |

| Vomiting | 14 (14) | 0 | 20 (21) | 2 (2) | 15 (17) | 1 (1) | 13 (21) | 4 (7) |

| GGT increased | 12 (12) | 4 (4) | 9 (9) | 5 (5) | 5 (6) | 1 (1) | 3 (5) | 1 (2) |

| Anorexia | 11 (11) | 4 (5) | 15 (16) | 12 (12) | 6 (7) | 2 (2) | 8 (13) | 4 (7) |

| Febrile neutropeniab | 6 (6) | 5 (5) | 43 (44) | 43 (44) | 0 | 0 | 28 (45) | 28 (45) |

| Mucositis oralb | 4 (4) | 0 | 44 (45) | 25 (26) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 16 (26) | 5 (8) |

| Sepsisb | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 13 (13) | 13 (13) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 14 (23) | 14 (23) |

| Typhlitis | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 4 (7) | 4 (7) |

| Blinatumomab-related adverse event | ||||||||

| Cytokine release syndromed | 22 (22) | 1 (1) | NA | NA | 1 (1) | 0 | NA | NA |

| Encephalopathy | 11 (11) | 2 (2) | NA | NA | 7 (8) | 2 (2) | NA | NA |

| Seizure | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | NA | NA | 1 (1) | 0 | NA | NA |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Grading was performed according to the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.0). Grading ranges from 1 to 5, with 3 indicating severe or medically significant but not immediately life-threatening; 4, life-threatening and indicating urgent intervention; and 5, death. Grades were assigned by the treating physician and select serious adverse events, as defined in the protocol, are reported per federal guidelines.

These 4 adverse events of special interest were identified based on their known association with life-threatening complications.

Includes catheter-related, lung, skin, upper respiratory tract, and urinary tract infections.

Cytokine release syndrome is a toxicity caused by rapid release of cytokines into the blood known to occur with immunotherapies including blinatumomab. Signs and symptoms of cytokine release syndrome include fever, nausea, headache, rash, tachycardia, hypotension, and tachypnea.

Four AEs of special interest were identified based on their known association with life-threatening complications (infection, febrile neutropenia, mucositis, and sepsis). The cumulative rates of these AEs in the blinatumomab group were 15% for infection, 5% for febrile neutropenia, 1% for mucositis, and 2% for sepsis (eTable 7 in Supplement 2). The cumulative rates of these AEs in the chemotherapy group were 65% for infection, 58% for febrile neutropenia, 28% for mucositis, and 27% for sepsis (eTable 7 in Supplement 2). There were 5 toxic deaths during chemotherapy cycles 1 and 2 (all infections) vs none during blinatumomab cycles 1 and 2. Four of the 5 toxic deaths were adolescent and young adult patients (aged 14, 17, 23, and 26 y). The rates of blinatumomab-related AEs of any grade and of greater than or equal to grade 3 were as follows: 22% and 1% in cycle 1 and 1% and 0% in cycle 2 for cytokine release syndrome, 11% and 2% in cycle 1 and 8% and 2% in cycle 2 for encephalopathy, and 4% and 1% in cycle 1 and 1% and 0% in cycle 2 for seizure (Table 3). All blinatumomab-related AEs were fully reversible, with no AE-related deaths. Of 102 patients who underwent cycle 1 and 88 patients who underwent cycle 2 in the blinatumomab group, 19 (19%) and 15 (17%) had a blinatumomab dose reduction based on protocol-specified criteria (eAppendix in Supplement 1).

Subgroup Outcomes

Analyses of disease-free survival, overall survival, MRD, rates of transplant, and events for the high- and intermediate-risk subgroups are shown in the eFigure and eTable 8 in Supplement 2. Analyses of baseline characteristics, disease-free survival, and overall survival for adolescent and young adult (aged 18-30 years) and child (aged <18 years) subgroups are shown in eTable 9 and the eFigure in Supplement 2.

Exploratory End Point: Outcomes for Patients Ineligible for Randomization Due to Early Treatment Failure

A total of 45 patients met criteria for early treatment failure (eTable 10 in Supplement 2) and were not eligible for randomization. Three had persistent CNS disease and were ineligible to receive salvage blinatumomab. Among the 42 patients with early treatment failure who were eligible, 20 pursued other therapies and 22 received salvage blinatumomab. Five of 22 patients (23%) had morphologic remission (<5% marrow blasts) after 1 cycle of salvage blinatumomab. Of these 5 patients, 3 had negative MRD after either 1 cycle (n = 2) or 2 cycles (n = 1). All 3 patients who had negative MRD proceeded to transplant. The 2 patients who did not have negative MRD did not proceed to transplant in remission.

Discussion

Among children, adolescents, and young adults with high- and intermediate-risk first relapse of B-ALL, postreinduction treatment with blinatumomab, compared with chemotherapy, followed by hematopoietic stem cell transplant did not result in a statistically significant difference in disease-free survival. Because the randomization was terminated early by the independent data and safety monitoring board, the primary analysis set included 208 patients instead of the planned 220, so it is possible that the trial was underpowered for the primary endpoint of disease-free survival.

Patients with early treatment failure with at least 25% marrow blasts after reinduction chemotherapy were not eligible for randomization, but were eligible to receive up to 2 blinatumomab cycles. Based on the experience of the 22 patients with early treatment failure who were nonrandomly assigned to receive blinatumomab therapy, the success rate in the salvage setting was low. This outcome supports findings of previous studies that identified high bone marrow blast percentage as a risk factor for blinatumomab resistance.13,14

The recommendation of early termination of the high- and intermediate-risk randomization was based not on the triggering of the predefined disease-free survival–based or adverse event–based stopping rule, but rather on a combined assessment of disease-free survival and the predefined secondary and exploratory end points of overall survival, MRD, and comparative adverse event profiles, all of which favored blinatumomab over chemotherapy. The data and safety monitoring committee concluded that the totality of data demonstrated a loss of clinical equipoise.

To our knowledge, this is the first randomized trial suggesting a survival benefit for immunotherapy in patients with B-ALL. The TOWER study of adults with relapsed or treatment-refractory ALL showed increased median survival duration from 4 months with chemotherapy to 7.7 months with blinatumomab, but there was no statistically significant difference in overall survival.13 Similarly, the INO-VATE randomized study, including adults with relapsed/refractory B-ALL, of the anti-CD22 immunoconjugate inotuzumab showed increased median survival duration but no difference in survival.25 Nonrandomized trials of blinatumomab for adults with MRD-positive B-ALL and of CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cells in patients aged 3 to 25 years with relapsed/refractory B-ALL showed improved overall survival, but are limited by historical control comparisons.15,26

The goal of treatment for participants in this trial was to provide a “bridge” to stem cell transplant, which is necessary to achieve durable remission. Trial participants treated with blinatumomab had higher rates of becoming MRD-negative and lower rates of AEs than the group treated with chemotherapy, which may explain the higher percentage of participants who were able to continue to transplant. The survival benefit of blinatumomab compared with chemotherapy is likely derived from the percentage of patients who were able to undergo transplant. This trial was designed for all patients to receive 2 cycles of either chemotherapy or blinatumomab followed by transplant. Given the high rate of MRD negativity after cycle 1 of blinatumomab and because some patients who had negative MRD after the first blinatumomab cycle reverted to having positive MRD after the second cycle, future trials should test proceeding directly to transplant after 1 blinatumomab cycle for patients that have MRD negativity. Conversely, continuation of blinatumomab for a second cycle may be appropriate in patients with MRD positivity, because one-third of these patients had MRD negativity after the second cycle of blinatumomab.

The efficacy of blinatumomab relative to chemotherapy for patients with low-risk relapsed B-ALL who are not treated with transplant is not yet known. Study results for the low-risk cohort in this trial will be informative, but have not yet been released by the data and safety monitoring committee.

This trial included patients aged 18 to 30 years, which accounted for 16% of the randomized participants. The UKALLR3 study, the model for the control chemotherapy treatment in this trial, only included patients aged 18 years and younger.4 Although the current trial demonstrates the feasibility of incorporating young adults into pediatric cooperative group relapse ALL trials, it also highlights the challenge of greater chemotherapy-related toxicity in young adults.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the disease-free survival comparison is underpowered due to early termination of the high- and intermediate-risk randomization. Second, interpretation of the secondary, exploratory, and post hoc end points is limited by the lack of planned adjustment for multiple comparisons. Third, the transplant procedures (eg, donor, preparatory regimen) were not fully standardized or prescribed, and thus varied among trial participants.

Conclusions

Among children, adolescents, and young adults with high- and intermediate-risk first relapse of B-ALL, postreinduction treatment with blinatumomab, compared with chemotherapy, followed by transplant did not result in a statistically significant difference in disease-free survival. However, study interpretation is limited by early termination with possible underpowering for the primary end point.

Trial protocol and statistical analysis plan

eTable 1. Reinduction treatment

eTable 2. Randomized treatment, blinatumomab group

eTable 3. Randomized treatment, chemotherapy group

eTable 4. Non-randomized treatment, early treatment failure group

eTable 5. MRD transitions

eTable 6. CD19 expression for blinatumomab patients with recurrent MRD

eTable 7. Adverse event summary (cumulative for cycle 1 and cycle 2)

eTable 8. MRD, transplant rates and events according to risk groups

eTable 9. Baseline characteristics for randomized patients by age group

eFigure. Survival plots for subgroups

eTable 10. Baseline characteristics for early treatment failure patients

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Nguyen K, Devidas M, Cheng SC, et al. ; Children’s Oncology Group . Factors influencing survival after relapse from acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Children’s Oncology Group study. Leukemia. 2008;22(12):2142-2150. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horton TM, Whitlock JA, Lu X, et al. Bortezomib reinduction chemotherapy in high-risk ALL in first relapse: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Br J Haematol. 2019;186(2):274-285. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raetz EA, Cairo MS, Borowitz MJ, et al. Re-induction chemoimmunotherapy with epratuzumab in relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): phase II results from Children’s Oncology Group (COG) study ADVL04P2. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(7):1171-1175. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parker C, Waters R, Leighton C, et al. Effect of mitoxantrone on outcome of children with first relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL R3): an open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9757):2009-2017. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62002-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tallen G, Ratei R, Mann G, et al. Long-term outcome in children with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia after time-point and site-of-relapse stratification and intensified short-course multidrug chemotherapy: results of trial ALL-REZ BFM 90. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(14):2339-2347. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Locatelli F, Schrappe M, Bernardo ME, Rutella S. How I treat relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2012;120(14):2807-2816. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-265884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oskarsson T, Soderhall S, Arvidson J, et al. Treatment-related mortality in relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(4). doi: 10.1002/pbc.26909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pulsipher MA, Carlson C, Langholz B, et al. IgH-V(D)J NGS-MRD measurement pre- and early post-allotransplant defines very low- and very high-risk ALL patients. Blood. 2015;125(22):3501-3508. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-12-615757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bader P, Salzmann-Manrique E, Balduzzi A, et al. More precisely defining risk peri-HCT in pediatric ALL: pre- vs post-MRD measures, serial positivity, and risk modeling. Blood Adv. 2019;3(21):3393-3405. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lew G, Chen Y, Lu X, et al. Outcomes after late bone marrow and very early central nervous system relapse of childhood B-Acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Children's Oncology Group phase III study AALL0433. Haematologica. 2021;106(1):46-55. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.237230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eckert C, Groeneveld-Krentz S, Kirschner-Schwabe R, et al. ; ALL-REZ BFM Trial Group . Improving stratification for children with late bone marrow B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia relapses with refined response classification and integration of genetics. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(36):3493-3506. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker C, Krishnan S, Hamadeh L, et al. Outcomes of patients with childhood B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia with late bone marrow relapses: long-term follow-up of the ALLR3 open-label randomised trial. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6(4):e204-e216. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(19)30003-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kantarjian H, Stein A, Gökbuget N, et al. Blinatumomab versus chemotherapy for advanced acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(9):836-847. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1609783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von Stackelberg A, Locatelli F, Zugmaier G, et al. Phase i/phase ii study of blinatumomab in pediatric patients with relapsed/refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(36):4381-4389. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.3301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gökbuget N, Dombret H, Bonifacio M, et al. Blinatumomab for minimal residual disease in adults with B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2018;131(14):1522-1531. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-08-798322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borowitz MJ, Devidas M, Hunger SP, et al. ; Children’s Oncology Group . Clinical significance of minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and its relationship to other prognostic factors: a Children’s Oncology Group study. Blood. 2008;111(12):5477-5485. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-132837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cherian S, Miller V, McCullouch V, Dougherty K, Fromm JR, Wood BL. A novel flow cytometric assay for detection of residual disease in patients with B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma post anti-CD19 therapy. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2018;94(1):112-120. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.21482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunsmore KP, Winter SS, Devidas M, et al. Children’s Oncology Group AALL0434: a phase III randomized clinical trial testing nelarabine in newly diagnosed T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(28):3282-3293. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.00256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larsen EC, Devidas M, Chen S, et al. Dexamethasone and high-dose methotrexate improve outcome for children and young adults with high-risk b-acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from Children’s Oncology Group study AALL0232. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(20):2380-2388. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.4544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lan KKG, Demets DL. Discrete sequential boundaries for clinical trials. Biometrika. 1983;70(3):659-663. doi: 10.1093/biomet/70.3.659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Brien PC, Fleming TR. A multiple testing procedure for clinical trials. Biometrics. 1979;35(3):549-556. doi: 10.2307/2530245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freidlin B, Korn EL. A comment on futility monitoring. Control Clin Trials. 2002;23(4):355-366. doi: 10.1016/S0197-2456(02)00218-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalbfleisch, JD, Prentice, RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81(3):515-526. doi: 10.1093/biomet/81.3.515. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kantarjian HM, DeAngelo DJ, Stelljes M, et al. Inotuzumab ozogamicin versus standard therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):740-753. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maude SL, Laetsch TW, Buechner J, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(5):439-448. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol and statistical analysis plan

eTable 1. Reinduction treatment

eTable 2. Randomized treatment, blinatumomab group

eTable 3. Randomized treatment, chemotherapy group

eTable 4. Non-randomized treatment, early treatment failure group

eTable 5. MRD transitions

eTable 6. CD19 expression for blinatumomab patients with recurrent MRD

eTable 7. Adverse event summary (cumulative for cycle 1 and cycle 2)

eTable 8. MRD, transplant rates and events according to risk groups

eTable 9. Baseline characteristics for randomized patients by age group

eFigure. Survival plots for subgroups

eTable 10. Baseline characteristics for early treatment failure patients

Data sharing statement