Abstract

Previous literature about the structural characterization of the human cerebellum is related to the context of a specific pathology or focused in a restricted age range. In fact, studies about the cerebellum maturation across the lifespan are scarce and most of them considered the cerebellum as a whole without investigating each lobule. This lack of study can be explained by the lack of both accurate segmentation methods and data availability. Fortunately, during the last years, several cerebellum segmentation methods have been developed and many databases comprising subjects of different ages have been made publically available. This fact opens an opportunity window to obtain a more extensive analysis of the cerebellum maturation and aging. In this study, we have used a recent state‐of‐the‐art cerebellum segmentation method called CERES and a large data set (N = 2,831 images) from healthy controls covering the entire lifespan to provide a model for 12 cerebellum structures (i.e., lobules I‐II, III, IV, VI, Crus I, Crus II, VIIB, VIIIA, VIIIB, IX, and X). We found that lobules have generally an evolution that follows a trajectory composed by a fast growth and a slow degeneration having sometimes a plateau for absolute volumes, and a decreasing tendency (faster in early ages) for normalized volumes. Special consideration is dedicated to Crus II, where slow degeneration appears to stabilize in elder ages for absolute volumes, and to lobule X, which does not present any fast growth during childhood in absolute volumes and shows a slow growth for normalized volumes.

Keywords: aging, cerebellum trajectory, lifespan, maturation, MRI segmentation, patch‐based processing

In this work, we provide growth models for cerebellum lobules and tissues across the entire lifespan using 2,512 publicly available brain images.

1. INTRODUCTION

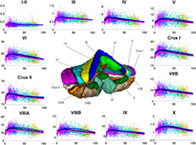

The human cerebellum, located below the cerebrum, is an important bilateral neuroanatomical structure connected to the cerebrum and the brain stem by means of two white matter fiber tracts called the cerebellar peduncles. At the opposite end of the peduncles, a series of gray matter folds called foliations can be grouped in left, right, and vermal (a central portion of the cerebellum) lobes. These lobes can also be classified into lobules. In this study, we used a cerebellum lobule classification consisting in 12 bilateral structures: lobules I‐II, III, IV, VI, Crus I, Crus II, VIIB, VIIIA, VIIIB, IX, and X (Park et al., 2014). Figure 1 shows an example of this segmentation protocol. Lobules are located surrounding the white matter starting by lobules I‐II and ending with lobule X following the order mentioned beforehand. Note that lobules I‐II are barely seen in Figure 1 since they represent a small portion of the cerebellar volume containing just a few voxels while the rest of the lobules have much larger volumes.

FIGURE 1.

Cerebellum segmentation protocol

The cerebellum has been related to motor tasks for a long time (Compston & Coles, 2008; Davie et al., 1995; Kase et al., 1993; Klockgether, 2008). However, more recent studies showed that the cerebellum is also involved in many cognitive functions (Middleton & Strick, 1997) such as language, learning and memory (Desmond, Gabrieli, & Glover, 1998; Riva & Giorgi, 2000; Stoodley & Schmahmann, 2009) and in emotional process (Schmahmann & Sherman, 1998). In fact, patients with cerebellar lesions limited to lobule VI experienced minimal motor impairment (Stoodley & Schmahmann, 2010). Specific cerebellum dysfunction have also been associated to cognitive impairment in various pathological conditions such as schizophrenia (Okugawa et al., 2002; James, James, Smith, & Javaloyes, 2004, Laidi et al., 2019, Nenadic et al., 2010), Alzheimer's disease (Thomann et al., 2008), Multiple Sclerosis (Moroso et al., 2017) and neurodevelopmental disorders Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism (Bishop, 2002; Courchesne et al., 1994; Ramnani, 2006; Seidman, Valera, & Makris, 2005).

In neuroimaging studies, different cerebellum lobules have been demonstrated to be involved in particular sensorimotor tasks and/or higher functions (Diamond, 2000; Habas et al., 2009; Krienen & Buckner, 2009; O'Reilly, Beckmann, Tomassini, Ramnani, & Johansen‐Berg, 2010). Finger tapping activates lobules IV, V, VIIIA, and VIIIB. Observing rotated letters involves activity in lobules VI, VIIB, and Crus II. Viewing emotional images produces activations in lobule VI. For memory tasks, activation peaks appeared in lobules V, VI, and Crus I. (Stoodley, Valera, & Schmahmann, 2012). Far beyond its initial role in motor skills, a growing body of literature supports the role of the cerebellum in a large panel of complex behaviors. Functional classification of cerebellum substructures based on either subjects presenting lesions (Stoodley & Schmahmann, 2010) or on functional connectivity recorded at rest (Guell, Schmahmann, Gabrieli, & Ghosh, 2018) revealed functional subdivisions of the cerebellum networks: double motor representation of the sensorimotors (lobules I–VI and VIII) and the triple nonmotor representations (lobules VI‐Crus I, Crus II–VIIB, IX–X). However, its mode of operation is still far from being elucidated. Its role in learning processes and adaptive plasticity suggests that it would play a key role during the development stages. In accordance, clinical studies indicate that cerebellum injuries occurring in childhood have much more dramatic functional consequences than when they occur in adulthood (Badura et al., 2018; Stoodley, 2016).

To gain a better understanding of how neurological structures are related to normal and pathological functions, the study of the evolution of their volume represents a valuable tool. For this reason, several previous works analyzed the evolution of different cerebrum and cerebellum structures at different age ranges. Luft et al. (1999) studied age‐related shrinkage patterns in subjects from 19 to 73 years old using 11 cerebellar structures. Sullivan et al., (2000) studied the effect different degrees of alcoholism in subjects between 23 and 72 years old using cerebellar hemispheres and four vermis regions. Jernigan et al. (2001) conducted a study with patients from 30 to 99 years old using cerebellar gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid. Raz et al. (2005) studied the evolution of the whole cerebellum volume on healthy adults over 49 years old. Fan et al. (2010) also found evidences of sexual dimorphism in a study with patients between 18 and 33 years old using 10 lobules and Tiemeier et al. (2010) showed that cerebellum maturation process extends to late adolescence presenting an inverted U‐shaped trajectory using images from patients with ages comprised between 5 and 24 years old and dividing the cerebellum into three main lobes and corpus medullare. Wierenga et al. (2014) focused in cerebellar cortex and an age range from 7 to 24 years old. Most recently, Sullivan et al. (2020) studied the effect of alcoholism in adolescence in healthy adolescents from 12 to 21 years old using 10 cerebellar structures. All these previous studies considered narrow age range in moderate samples size and they are based on various level of segmentation (global, lobes, lobules, tissue type). All these differences make it difficult to clearly describe a lifelong evolution of the cerebellum. Recently, (Han, An, Carass, Prince, & Resnick, 2020) conducted a study using 2,023 images from 822 participants comprising ages from 55 to 90 years old. They found that cerebellum volume trajectories vary spatially over time. Also found significant differences, both longitudinal and cross‐sectional, and five of the 28 studies cerebellar regions presented significant sex effects at baseline.

In this paper, we present a series of models of the trajectory of the cerebellum lobules based on a large set of 2,515 images. This set is covering a wide age range (from 1 to 94 years old) to produce robust and valuable normal growth models across the entire lifespan, as previously done by Coupé et al. in 2017.

Obtaining unbiased or unrestricted conclusions applicable to the entire lifespan is challenging. We have addressed this in two ways. First, we took advantage of the new Big Data sharing paradigm in neuroimaging (Poldrack and Gorgolewski, 2014) which gave us access to a large number of subjects (N = 2,831 before our quality control) comprising ages from 9 months to 94 years. Second, the images (gathered from different freely available data sets) have been processed using the same cerebellum segmentation pipeline (Romero et al., 2017). These images and their segmentation results were examined through a demanding multistage quality control to avoid poor quality acquisitions and segmentation errors that could affect the trajectories. To analyse the results and produce new knowledge, we modeled every structure growth with the best model between several options. We compared six models from simplest (linear) to most complex (hybrid) model as done in (Coupé et al., 2017) that cope with fast growth during development and slow atrophy during aging.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Image data

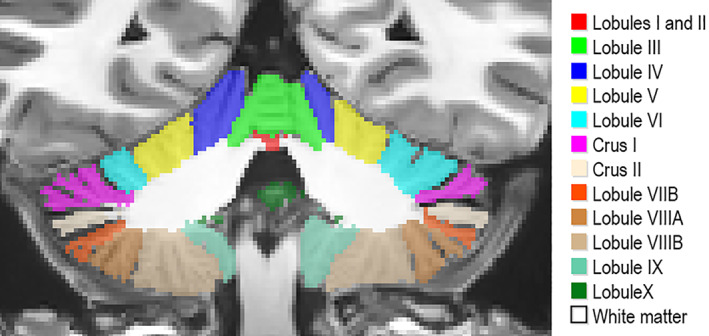

To perform this study, we used 2,515 from the total set of 2,832 after quality control. The data set consists of 3D MRI T1‐weighted images from healthy controls obtained from nine freely available data sets. The subjects have an age range from 1 to 94 years. Figure 2 shows the age distribution.

FIGURE 2.

Age distribution of cases used after quality control. Left chart shows age distribution for all the considered subjects. Right chart shows age distribution for child under 10 years old. Legend indicates the number of images for each data set after the quality control

The details of each data set are given below. In addition, Table 1 shows a summary of the information extracted from each data set:

TABLE 1.

Data set summary

| Data set | Acquisition | Before QC | After QC | Gender after QC | Age in years after QC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C‐MIND | 1 site with 3 T MR scanner | 266 | 182 |

F = 101 M = 81 |

8.77 (4.53) [1.09–18.86] |

| NDAR | 10 sites with 1.5 T and 3 T MR scanner | 147 | 135 |

F = 26 M = 109 |

15.35 (9.33) [6.75–60] |

| ABIDE | 20 sites with 3 T MR scanner | 528 | 450 |

F = 74 M = 376 |

17.50 (7.76) [6.5–56.2] |

| ICBM | 1 sites with 1.5 T MR scanner | 308 | 289 |

F = 140 M = 149 |

33.96 (14.34) [18–80] |

| IXI | 3 sites with 1.5 T and 3 T MR scanner | 588 | 519 |

F = 292 M = 227 |

48.90 (16.38) [19.98–86.2] |

| OASIS1 | 1 sites with 1.5 T MR scanner | 315 | 290 |

F = 182 M = 108 |

45.46 (23.80) [18–94] |

| AIBL | 2 sites with 1.5 T and 3 T MR scanners | 236 | 230 |

F = 121 M = 109 |

72.23 (6.70) [60–89] |

| ADNI 1 | 51 sites with 1.5 T MR scanner | 228 | 218 |

F = 107 M = 111 |

75.87 (5.01) [60–90] |

| ADNI 2 | 14 sites with 3 T MR scanners | 215 | 202 |

F = 109 M = 93 |

74.20 (6.44) [56.3–89] |

| Total | 103 sites with 1.5 T and 3 T scanners | 2,831 | 2,515 |

F = 1,152 (46%) M = 1,363 (54%) |

42.97 (26.07) [1.09–94] |

C‐MIND (N = 266, after QC N = 182): The images from the C‐MIND data set (https://research.cchmc.org/c-mind/) used in this study consist of 266 control subjects. All the images were acquired at the same site on a 3 T scanner. The MRI are 3D T1‐weighted MPRAGE high‐resolution anatomical scan of the entire brain with spatial resolution of 1 mm3 acquired using a 32 channel SENSE head‐coil.

NDAR (N = 147, after QC N = 135): The National Database for Autism Research (NDAR) is a national database funded by NIH (https://ndar.nih.gov). This database included 13 different cohorts acquired on 1.5 T MRI and 3 T scanners. In our study, we used 147 images of control subjects from the Lab Study 19 of National Database for Autism Research. For the NIHPD, T1‐weighted images were acquired at six different sites with 1.5 Tesla systems by General Electric (GE) and Siemens Medical Systems. The MRI are 3D T1‐weighted spoiled gradient recalled (SPGR) echo sequence with following parameters: TR = 22–25 ms, TE = 10–11 ms, flip angle = 30°, FoV = 256 mm IS × 256 mm AP, matrix size = 256 × 256:1 × 1 × 1 mm3 voxels, 160–180 slices of sagittal orientation. The participants chosen from the Lab Study 19 of NDAR were scanned using a 3 T Siemens Tim Trio scanner at each site. The MRI are 3D MPRAGE sequence (voxel dimensions: 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm3; image dimensions: 160 × 224 × 256, TE = 3.16 ms, TR = 2,400 ms).

ABIDE (N = 528, after QC N = 450): The images from the Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE) data set (http://fcon_1000.projects.nitrc.org/indi/abide/) used in this study consist of 528 control subjects acquired at 20 different sites on 3 T scanner. The MRI are T1‐weight MPRAGE image and the details of acquisition, informed consent, and site‐specific protocols are available on the website.

ICBM (N = 308, after QC N = 289): The images from the International Consortium for Brain Mapping (ICBM) data set (http://www.loni.usc.edu/ICBM/) used in this study consist of 308 normal subjects obtained through the LONI website. The MRI are T1‐weighted MPRAGE (fast field echo, TR = 17 ms, TE = 10 ms, flip angle = 30°, 256 × 256 matrix, 1 mm2 in plane resolution, 1 mm thick slices) acquired on a 1.5 T Philips GyroScan imaging system (Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands).

OASIS1 (N = 315, after QC N = 290): The images from the open access series of imaging studies (OASIS1) database (http://www.oasis-brains.org) used in this study consist of 315 control subjects. The MRI are T1‐weighted MPRAGE image (TR = 9.7 ms, TE = 4 ms, TI = 20 ms, flip angle = 10°, slice thickness = 1.25 mm, matrix size = 256 × 256, voxel dimensions = 1 × 1 × 1.25 mm3 resliced to 1 mm3, averages = 1) acquired on a 1.5‐T Vision scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany).

IXI (N = 588, after QC N = 519): The images from the Information eXtraction from Images (IXI) database (http://brain-development.org/ixi-dataset/) used in this study consist of 588 normal subjects. The MRI are T1weighted images collected at 3 sites with 1.5 and 3 T scanners (FoV = 256 mm × 256 mm, matrix size = 0.9375 × 0.9375 × 1.2 mm3).

ADNI1 (N = 228, after QC N = 218): The images from the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (http://adni.loni.usc.edu) used in this study consist of 228 control subjects from the 1.5 T baseline collection. These images were acquired on 1.5 T MR scanners at 60 different sites across the United States and Canada. A standardized MRI protocol to ensure cross‐site comparability was used. Typical MRI are 3D sagittal MPRAGE (repetition time (TR): 2,400 ms, minimum full TE, inversion time (TI): 1,000 ms, flip angle: 8°, 24 cm field of view, and a 192 × 192 × 166 acquisition matrix in the x‐, y‐, and z‐ dimensions, yielding a voxel size of 1.25 × 1.25 × 1.2 mm3, later reconstructed to get 1 mm3 isotropic voxel resolution).

ADNI2 (N = 215, after QC N = 202): The images from the ADNI2 database (second phase of the ADNI project) consist of 215 control subjects. Images were acquired on 3 T MR scanners with the standardized ADNI‐2 protocol, available online (www.loni.usc.edu). Typical MRI are T1‐weighted 3D MPRAGE sequence (repetition time 2,300 ms, echo time 2.98 ms, flip angle 9°, field of view 256 mm, resolution 1.1 × 1.1 × 1.2 mm3).

AIBL (N = 236, after QC = 230): The Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) database (http://www.aibl.csiro.au/) used in this study consists of 236 control subjects. The imaging protocol was defined to follow ADNI's guideline on the 3 T scanner (http://adni.loni.ucla.edu/research/protocols/mri-protocols) and a custom MPRAGE sequence was used on the 1.5 T scanner.

2.2. Image processing

All the images used in this study were processed using CERES pipeline (Romero et al., 2017) (part of the volBrain platform: http://volbrain.upv.es). volBrain is an open access online platform that provides Brain MRI processing including preprocessing and segmentation in a fully automated manner for academic and research purposes (Manjón & Coupe, 2016). Since it was launched in 2015, it has deployed five different segmentation pipelines (freely accessible to the scientific community) and currently is being used by more than 4,500 users (from more than 1700 academic and research centers around the world) and more than 245,000 cases have been already processed online.

The CERES preprocessing pipeline consists of a series of steps aimed to both enhance the image quality and transform the image to a common coordinate and intensity space. This preprocessing also aims to harmonize image features across individuals, sites, and manufacturers. The steps are the following: (a) Denoising using the spatially adaptive nonlocal means filter (Manjón, Tohka, & Robles, 2010) to reduce noise. (b) Inhomogeneity correction in native space using N4 bias field correction (Tustison et al., 2010) to improve the registration. (c) Affine registration to the MNI (Montreal Neurological Institute) space using ANTs (Avants, Tustison, & Song, 2009) and the MNI152 template. (d) Region of interest cropping around cerebellum area to reduce the computational burden. (e) Low dimensional nonlinear registration estimation using ANTs (Avants et al., 2009). CERES uses a registration strategy to move the whole template library to the case to be segmented space estimating only one transformation. The details of this step are described in the original paper (Romero et al., 2017). (f) Intensity normalization based on ROIs as done in (Asman & Landman, 2012) to achieve that all the cerebellum tissues have the same intensity across the data set.

The segmentation step consists of a patch‐based algorithm called OPAL (Giraud et al., 2016; Ta, Giraud, Collins, & Coupé, 2014) which uses an optimized version of the nonlocal label fusion (Coupé et al., 2011) using Patch Match (Barnes, Shechtman, Finkelstein, & Goldman, 2009). A data set of 10 (5 left–right flipped) T1‐weighted high‐resolution (0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5 mm after preprocessing) images manually segmented by experts into 26 structures (right and left lobules I‐II, III, IV, VI, Crus I, Crus II, VIIB, VIIIA, VIIIB, IX, X, and white matter) was used to construct the template library. The HR images were obtained from the CoBrALab site (http://cobralab.ca/atlases/Cerebellum.html). For more details about the image data, see (Park et al., 2014). In addition, to obtain the total intracranial volume (TIV) we used the segmentation method NICE (Manjon et al., 2014).

CERES segments the cerebellum in 26 structures, 13 on the left 13 on the right. One of the 13 structures is the white matter. Since we did not consider lateralization here, right and left volumes have been combined and finally 12 gray matter regions have been studied. For white matter segmentation, results have been presented with the whole cerebellum analysis.

2.3. Statistical analysis

It is common to find studies that use low order polynomial function to model structure volume trajectories as done in (Walhovd et al., 2011) where linear and quadratic models are used to model basal ganglia and brainstem aging over adulthood. In (Tiemeier et al., 2010) the author used cubic function to model cerebellum lobes trajectory across adolescence. Some studies have used Poisson curve (Lebel et al., 2012) or Gompertz‐like function (Makropoulos et al., 2016) to model fast brain development in childhood. Combining fast development occurring during childhood and slow aging occurring over adulthood requires more advanced models. Coupé et al. (2017) proposed to model fast growth in childhood and slow atrophy using hybrid models. We have tested several functions to model the trajectories for each structure under study and selected the best one. We compared them with decide which fits better the evolution of the cerebellar volumes across the lifespan as done in (Coupé et al., 2017) which are listed below:

|

1. Linear model | |

|

Vol = β 0 + β 1 Age + ε | |

|

2. Quadratic model | |

|

Vol = β 0 + β 1 Age + β 2 Age 2 + ε | |

|

3. Cubic model | |

|

Vol = β 0 + β 1 Age + β 2 Age 2 + β 3 Age 3 + ε | |

|

4. Linear hybrid model: Exponential cumulative distribution for growth with linear model aging | |

|

| |

|

5. Quadratic hybrid model: Exponential cumulative distribution for growth with quadratic model aging | |

|

| |

|

6. Cubic hybrid model: Exponential cumulative distribution for growth with cubic model aging | |

|

|

To select the best general model (no gender separation) for each structure, the six models are evaluated following three criteria. First, they are compared to the constant model using the F‐statistic (ANOVA) to determine if there exist significant differences (p < .05). Then, we require that all its coefficients are significant using a t‐statistic (p < .05). Finally, the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) is used to select the best model from the remaining candidates. BIC allow us to select the simplest model that represent most of the information.

Once a general model is selected, gender interactions in the trajectories are tested, β i Sex + β j Sex· Age in terms of volume and shape. All the statistic tests (t‐statistic, F‐statistic, BIC and R2) performed in this study were calculated using Matlab©.

2.4. Quality control

It has been demonstrated that quality control (QC) has a significant impact on trajectory results (Ducharme et al., 2016). In this study, we used a three stage QC to select adequate subjects consisting in the following steps. First, we removed 219 images (7.7% from the total) by visual inspection based on its image quality (this selection is shared with (Coupé et al., 2017) as we used the same data set). The second step was a visual inspection of the processing results of every subject done using the CERES PDF reports generated by volBrain platform. At this stage we validated preprocessing (denoising, intensity normalization, inhomogeneity correction, etc.), MNI registration, intracranial cavity extraction, cerebellum tissue classification and lobule segmentation. In this step, 492 images (15.1% from the total) were removed. Finally, we defined as possible outliers every case with a volume higher or lower than 2 SD of the estimated model for the total cerebellum volume model. After carefully checking this potential outlier cases by displaying its segmentation map using ITK Snap software (Yushkevich et al., 2006) we removed 70 more subjects (2.5% from the total). After the full QC process 2,515 remained from the 2,831 initial subjects (88.8% from the total).

3. RESULTS

A detailed explanation of the trajectories obtained for every structure and the justification of the selected model is listed below. We show both absolute volume models (cm3) and normalized volume models (absolute volume/Total Intracranial Volume in percent). As handedness is not available for all the cases in this study we decided to not consider lateralization.

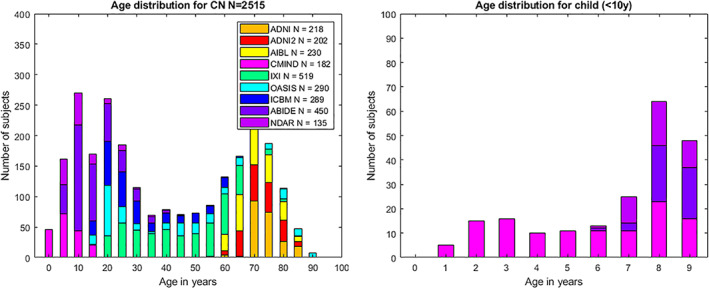

3.1. Cerebellum

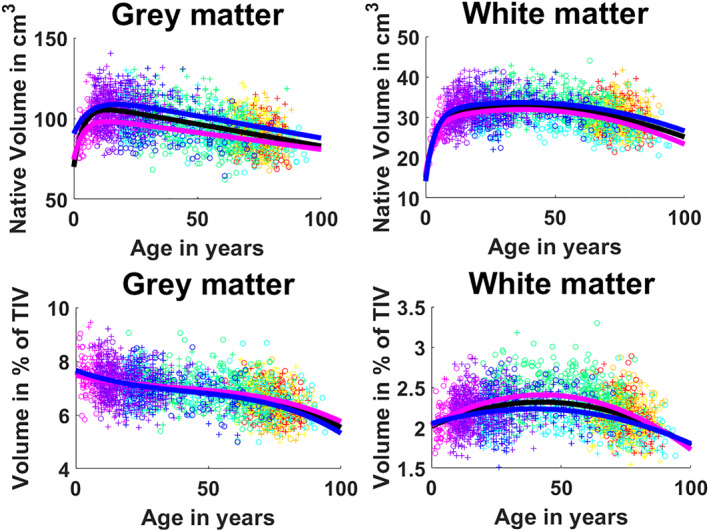

Cerebellum development and maturation, in absolute values, presents a rapid growth from 0 to 17 years for the general model (18 years for female and 21 years for male) followed by a slow decrease during the rest of the lifespan (See Figure 3). This is consistent with the model selection which resulted in a hybrid model combining an exponential cumulative distribution to represent the fast growth with a linear model to explain the slow decrease (p < .0001). In terms of normalized volumes, we found that the trajectory is divided in to three stages. First, a slow decrease (faster for male) until 25 years, followed by a plateau until 60–65 years and a slow decrease from this point (See Figure 3). This is consistent with Cubic model selected (p < .0001).

FIGURE 3.

Cerebellum trajectories for absolute values (left) and normalized values (right). General model is shown in black, female model in magenta and male model in blue. Dots color correspond to the different data sets used. Male cases are represented by “+”s and female cases are represented by “o”s

3.2. Cerebellum gray matter and white matter trajectories

In absolute values, we observe that WM presents a fast growth stage during youth that reaches its maximum around 10 years (See Figure 4). After this, WM shows an inverted U‐shape as it keeps growing slowly until 30–40 years. This trajectory is confirmed by the hybrid model selection (p < .0001) combining exponential cumulative distribution for growth and quadratic model for aging (See Table 2). For GM we have a similar fast growth during approximately the first 10 years followed by a constant slow decrease and a selected hybrid model combining an exponential cumulative distribution with a linear model (p < .0001). Focusing on the normalized volumes as percentage of the TIV, we see that GM shows a decreasing volume represented by a three‐stage trajectory, having a central plateau with slightly faster decreases in early years (until 25) and after the 60s which is modeled by a Cubic function (p < .0001) (see Table 3). For WM, despite the normalization, we still observe an inverted U‐shape with its maximum around 50 and a slightly faster degeneration than growth. The selected model for this was a cubic function (p < .0001).

FIGURE 4.

First row: Cerebellum gray matter and white matter trajectories for absolute values. Second row: Cerebellum gray matter and white matter trajectories for normalized values. General model is shown in black, female model in magenta and male model in blue. Dots color correspond to the different data sets used. Male cases are represented by “+”s and female cases are represented by “o”s

TABLE 2.

Model selection and statistics of model analysis for absolute volumes

| Absolute volume | Selected model | F‐statistic | R 2 | Model versus constant model p‐value of the F‐statistic based on ANOVA | Gender interaction p‐value of the t‐statistic on the coefficient | Age × gender interaction p‐value of the t‐statistic on the coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebellum | ||||||

| Global | Hybrid linear | 479 | .27 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p > .05 |

| Male | 223 | .25 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 193 | .25 | p < .0001 | |||

| Lobule I‐II | ||||||

| Global | Linear | 44.5 | .02 | p = .001 | p > .05 | p > .05 |

| Male | 26.7 | .02 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 5.55 | .004 | p = .019 | |||

| Lobule III | ||||||

| Global | Hybrid linear | 128 | .09 | p < .0001 | p > .05 | p > .05 |

| Male | 66.7 | .09 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 36.8 | .06 | p < .0001 | |||

| Lobule IV | ||||||

| Global | Hybrid linear | 303 | .19 | p < .0001 | p = .0002 | P > .05 |

| Male | 163 | .19 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 79.1 | .12 | p < .0001 | |||

| Lobule V | ||||||

| Global | Hybrid linear | 101 | .07 | p < .0001 | p = .006 | p > .05 |

| Male | 46.3 | .06 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 29 | .05 | p < .0001 | |||

| Lobule VI | ||||||

| Global | Hybrid linear | 313 | .2 | p < .0001 | p = .019 | p > .05 |

| Male | 141 | .17 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 118 | .17 | p < .0001 | |||

| Crus I | ||||||

| Global | Hybrid linear | 313 | .2 | p < .0001 | p = .002 | p > .05 |

| Male | 138 | .17 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 111 | .16 | p < .0001 | |||

| Crus II | ||||||

| Global | Hybrid second order | 192 | .19 | p < .0001 | p = .007 | p > .05 |

| Male | 87.5 | .16 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 63.7 | .14 | p < .0001 | |||

| Lobule VIIB | ||||||

| Global | Hybrid linear | 192 | .13 | p < .0001 | p = .006 | p > .05 |

| Male | 72.5 | .1 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 70.4 | .11 | p < .0001 | |||

| Lobule VIIIA | ||||||

| Global | Hybrid linear | 199 | .14 | p < .0001 | p = .0003 | p > .05 |

| Male | 72.6 | .1 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 80 | .12 | p < .0001 | |||

| Lobule VIIIB | ||||||

| Global | Hybrid linear | 155 | .11 | p < .0001 | p = .001 | p > .05 |

| Male | 55.8 | .07 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 70.1 | .11 | p < .0001 | |||

| Lobule IX | ||||||

| Global | Hybrid linear | 178 | .12 | p < .0001 | p = .03 | p > .05 |

| Male | 74.5 | .1 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 60.7 | .09 | p < .0001 | |||

| Lobule X | ||||||

| Global | Third order | 123 | .13 | p < .0001 | p = .04 | p > .05 |

| Male | 53.5 | .1 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 58.1 | .13 | p < .0001 | |||

| White matter | ||||||

| Global | Hybrid second order | 206 | .2 | p < .0001 | p = .05 | p > .05 |

| Male | 80.6 | .15 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 121 | .24 | p < .0001 | |||

| Gray matter | ||||||

| Global | Hybrid linear | 513 | .29 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | p > .05 |

| Male | 257 | .27 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 191 | .25 | p < .0001 | |||

TABLE 3.

Model selection and statistics of model analysis for normalized volumes

| Normalized volume | Selected model | F‐statistic | R 2 | Model versus constant model p‐value of the F‐statistic based on ANOVA | Gender interaction p‐value of the t‐statistic on the coefficient | Age × gender interaction p‐value of the t‐statistic on the coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebellum | ||||||

| Global | Third order | 237 | .22 | p < .0001 | p > .05 | p > .05 |

| Male | 169 | .27 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 96.9 | .2 | p < .0001 | |||

| Lobule I‐II | ||||||

| Global | Linear | 24.2 | .01 | p < .0001 | p > .05 | p > .05 |

| Male | 31 | .02 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 3.9 | .003 | p < .0001 | |||

| Lobule III | ||||||

| Global | Linear | 142 | .05 | p < .0001 | p > .05 | p > .05 |

| Male | 119 | .08 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 48.5 | .04 | p < .0001 | |||

| Lobule IV | ||||||

| Global | Third order | 143 | .15 | p < .0001 | p > .05 | p > .05 |

| Male | 120 | .21 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 4.8 | .09 | p < .0001 | |||

| Lobule V | ||||||

| Global | Second order | 31.1 | .02 | p < .0001 | p > .05 | p > .05 |

| Male | 29 | .04 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 12.1 | .02 | p < .0001 | |||

| Lobule VI | ||||||

| Global | Third order | 135 | .14 | p < .0001 | p > .05 | p > .05 |

| Male | 94.5 | .17 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 61.9 | .14 | p < .0001 | |||

| Crus I | ||||||

| Global | Linear | 397 | .14 | p < .0001 | p > .05 | p > .05 |

| Male | 283 | .17 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 143 | .11 | p < .0001 | |||

| Crus II | ||||||

| Global | Third order | 142 | .14 | p < .0001 | p > .05 | p > .05 |

| Male | 112 | .2 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 48.5 | .11 | p < .0001 | |||

| Lobule VIIB | ||||||

| Global | Third order | 81.3 | .09 | p < .0001 | p > .05 | p > .05 |

| Male | 58.6 | .11 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 31.8 | .07 | p < .0001 | |||

| Lobule VIIIA | ||||||

| Global | Linear | 234 | .09 | p < .0001 | p > .05 | p > .05 |

| Male | 109 | .07 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 103 | .08 | p < .0001 | |||

| Lobule VIIIB | ||||||

| Global | Second order | 100 | .07 | p < .0001 | p > .05 | p > .05 |

| Male | 41.6 | .06 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 51.7 | .08 | p < .0001 | |||

| Lobule IX | ||||||

| Global | Third order | 79.2 | .09 | p < .0001 | p > .05 | p > .05 |

| Male | 53.3 | .1 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 32.2 | .08 | p < .0001 | |||

| Lobule X | ||||||

| Global | Second order | 92.7 | .07 | p < .0001 | p > .05 | p > .05 |

| Male | 5.6 | .07 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 56.3 | .09 | p < .0001 | |||

| White matter | ||||||

| Global | Second order | 157 | .11 | p < .0001 | p = .05 | p > .05 |

| Male | 58.2 | .08 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 125 | .18 | p < .0001 | |||

| Gray matter | ||||||

| Global | Third order | 303 | .27 | p < .0001 | p > .05 | p > .05 |

| Male | 209 | .31 | p < .0001 | |||

| Female | 108 | .21 | p < .0001 | |||

3.3. Lobules I and II

Lobules I and II, which are treated as one structure in our segmentation protocol, showed an almost constant volume during the entire lifespan in both absolute and normalized volumes (see Figures 5 and 6) and this was supported by a selected linear model (p < .0001). It is important to note that, in our experience, the number of (visible) lobules can vary between subjects at 1 mm resolution. Indeed, the very difficult delineation task at 1 mm resolution of the smallest lobules may produce volumes near to zero. Therefore, segmentation errors can have huge effect when measuring small structures since the volume of a single voxel (1 × 1 × 1 mm3) start to be significant as it represents a greater percentage of the total volume compared to bigger structures. This may affect the trajectories of small structures as we are summarizing a whole structure in a few voxels. Lobules I and II are the smallest considered structures in this study, consequently these are the most impacted structures by using 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 resolution image.

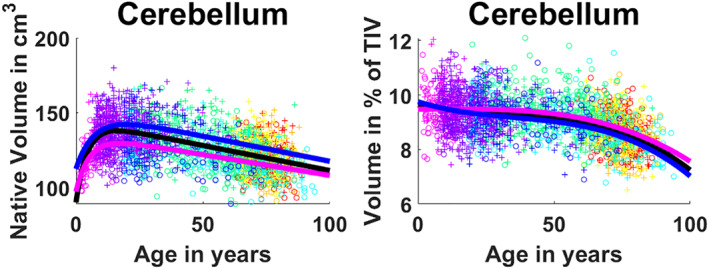

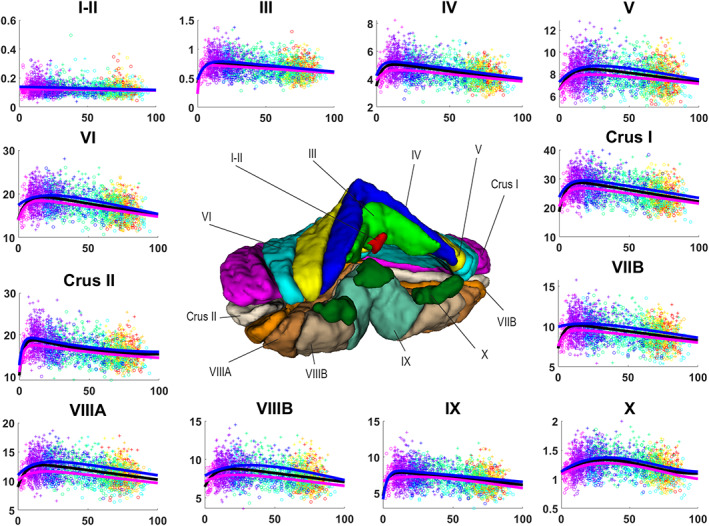

FIGURE 5.

Volume trajectories for absolute volumes in cm3 for cerebellum lobules. General model is shown in black, female model in magenta and male model in blue. Dots color correspond to the different data sets used. Vertical axis shows volume in cm3. Horizontal axis shows age in years. Male cases are represented by “+”s and female cases are represented by “o”s

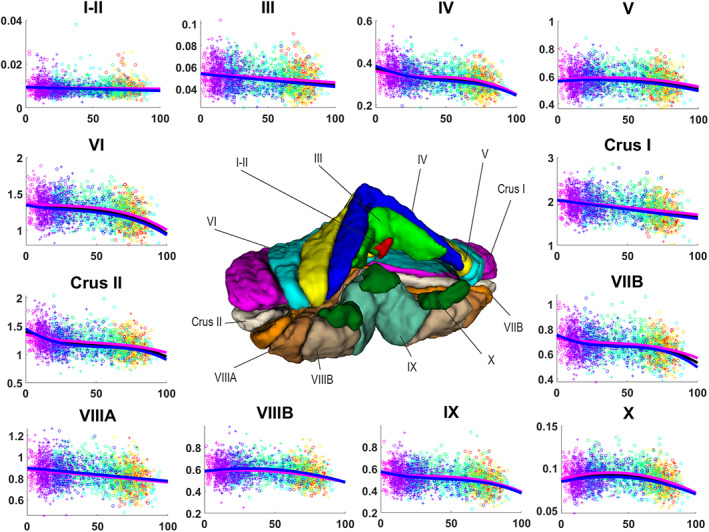

FIGURE 6.

Volume trajectories for normalized volumes for cerebellum lobules. General model is shown in black, female model in magenta and male model in blue. Dots color correspond to the different data sets used. Vertical axis shows volume in percentage to the TIV. Horizontal axis shows age in years. Male cases are represented by “+”s and female cases are represented by “o”s

3.4. Lobules III, IV, V, VI, Crus I, Crus II, VIIB, VIIIA, VIIIB, and IX

Analyzing the absolute values, lobules III, IV, V, VI, Crus I, VIIB, VIIIA, VIIIB, and IX presented a fast growth in early ages and a slow decrease during the rest of the lifespan (see Figure 5). Lobule IX showed the fastest growth reaching the maximum at around 5 years. The rest of the lobules (except for lobule VIIB) reached their maximums between 12 and 16 years. This was assessed by a hybrid linear model combing an exponential cumulative distribution during the fast growth and a linear function during aging (p < .0001). Lobule VIIIB showed a different trajectory for males presenting an inverted U‐shape which had its maximum around 30 years, being slightly asymmetrical with a faster aging than growth (see Figure 5) (p < .0001). Moreover, for the normalized values, lobules III, Crus I, and VIIA showed basically the same decrease ratio during the whole lifespan (see Figure 6) being represented by a selected linear model (p < .0001) while lobules IV, VI, and IX presented a more complex three‐stage trajectory composed by a slow decrease until around 20 years, followed by a plateau until 60–65 years, ending with a slow decrease. These trajectories were represented by a selected cubic model (p < .0001). Lobules V and VIIIB presented an inverted U‐shape trajectory adjusting to the pattern mentioned before (slightly faster growth) finding its maximum volume around 40 years (see Figure 5). These trajectories were modeled using a quadratic function (p < .0001). Finally, lobule VIIB presented a more complex trajectory composed by three stages starting by a fast decrease from 0 to 25 years followed by a plateau until 65–70 years to finish with another fast decrease (see Figure 5) which resulted in a selected cubic model (p < .0001). Crus II absolute values showed a rapid growth from 0 to around 7 years and then a slow decrease of the volume which is not linear neither an inverted U‐shape. It described a curve which reaches a plateau around 80 years and keep its volume constant from that point (see Figure 5). This is consistent with the model selection which results in a hybrid model (see Table 2) combining an exponential cumulative distribution with a quadratic function (p < .0001). For the normalized volume, Crus II presented a three‐stage trajectory starting with a fast decrease until 25 years following with a plateau and a second slightly slower decrease, starting at 60–66 years (see Figure 6), which corresponded to a cubic model selection (p < .0001).

3.5. Lobule X

At the global scale (absolute volumes), lobule X presented an inverted U‐shape trajectory that has a slow growth from 0 to around 30 years and a slow decrease from this point which tends to a plateau at 90 years (see Figure 5). A cubic model was selected (p < .0001) explaining this trajectory. For the normalized values the trajectory changed very little showing again an inverted U‐shape, this time with a slow growth until 40 years and a slow decrease (slightly faster than the growth) from this point (see Figure 6) resulting in a selected quadratic model (p < .0001).

3.6. Sexual dimorphism

Analyzing the absolute values, trajectories showed that males tend to have higher volumes. The whole cerebellum, the gray matter and the lobules IV and VIIIA showed significant sex differences (sex effect with p < .0001). Lobules V, VI, Crus I, VIIB, VIIIB, and IX also showed significant sex effect with p‐values under .006 (see Table 2). For the remaining structures sex effect did not reach statistical significance. As expected, relative volumes for male and female were not statistically different. Visual observation of Crus II and VIIB models suggests possible sex differences, one at the early ages and other for the elder cases.

4. DISCUSSION

In our study, we developed cerebellum maturation models covering the entire lifespan on a large sample size that lead to a better understanding of the cerebellum development and aging processes. According to our results, the cerebellum exhibits lifespan evolution principles common to cortex: an exponential growth starting for both compartments when raw volumes were considered and decline of gray matter and U‐shaped time course for white matter when normalized (Coupé et al., 2017). Moreover, we did not observe different lifespan pattern for the motor and the nonmotor counterparts described in functional classification of cerebellum substructures based on either subjects presenting lesions (Stoodley & Schmahmann, 2010) or on functional connectivity recorded at rest (Guell et al., 2018). Total cerebellum models for absolute values in the literature showed a descending linear trajectory from 19 to 73 years old (Luft et al., 1999). For adolescence ranges, trajectories followed an inverted U‐shape having its peak at 17 for males and 12 form females (Tiemeier et al., 2010). The same inverted U‐shape can be seen for males in (Wierenga et al., 2014) but not for females which showed a descending linear trajectory. These results (excepted for female models in Wierenga et al. (2014) are in line with our models which described a fast growth from 0 to 17 followed by a slow decrease for absolute values and a fairly constant decrease which accelerates at the end of the age interval. Regarding to normalized values, Raz et al., (2005) reported decreasing volumes in a baseline age representation for healthy participants over 49 years old for normalized volumes which is consistent with our findings. The same trajectories described for absolute values in (Tiemeier et al., 2010) are reported for normalized values. This is not in agreement with our models as we observed a slight decrease in normalized volumes during the childhood followed by a plateau during the adolescence.

Previous works reported descending trajectories for cerebellar gray matter. Sullivan et al. showed a linear descending trajectory from 19 to 73 years old (Sullivan, Deshmukh, Desmond, Lim, & Pfefferbaum, 2000) and obtained a quadratic descending curve from 12 to 21 years old for absolute values (Sullivan et al., 2020). These models are in line with our curves which showed a fast growth until 10 years old and a slow decrease for absolute values.

We showed a fast growth until 10 years old and a slow decrease for absolute values. This is in line with Sullivan et al. showing a linear descending trajectory from 19 to 73 years old (Sullivan et al., 2000) and obtained a quadratic descending curve from 12 to 21 years old for absolute values (Sullivan et al., 2020).

Regarding to cerebellar white matter trajectories, Sullivan et al. obtained a slowly ascending linear trajectory from 19 to 73 years old for absolute values (Sullivan et al., 2000) and reported a slow growth quadratic curve for the range of 12 to 21 years old (Sullivan et al., 2020). Our absolute volume models showed a fast growth of white matter until 10 years old followed by a flat U‐shape and a slow decrease from 40 years old for absolute values. This trajectory does not match perfectly with previous works trajectories but we think it is in good agreement if we take into account our larger age range which have an effect on the trajectory estimation.

(Temeire et al., 2010) obtained an inverted U‐shape trajectory for the ach inferior posterior lobe, superior posterior lobe and anterior lobe for absolute values. The inferior posterior lobe corresponds with our Crus II, VIIB, VIIIA, VIIIB, and IX. Comparing this trajectory with our results for the same age range we found that our models for lobules VIIB, VIIIB, and VIIIB are consistent with Tiemeier et al. (2010). However, our models for Crus II and lobule IX are slightly different as we obtained a linear decrease for IX and a slightly faster decrease for Crus II. We think that the fact that in (Tiemeier et al., 2010) consider the entire inferior posterior lobe could be hiding the differences between lobules. The superior posterior lobe corresponds to our VI, Crus I. The trajectory shown in (Tiemeier et al., 2010) is in line with our models for lobule VI and Crus I at the corresponding age range. Our models showed and inverted U‐shape following the fast growth. Finally, the anterior lobe corresponds to our lobules III, IV, and V. Tiemeier et al. (2010) results for anterior lobe matches with our models for lobules III, IV, and V that showed the same slightly curved inverted U‐shape.

Also, by using a segmentation protocol that divides the cerebellum in 12 structures, we provide specific results about sexual dimorphism (in absolute values) distinguishing lobules IV, V, VI, Crus I, VIIB, VIIIA, and VIIIB that significantly presented gender effect while the rest of lobules were not affected (Lobule IX showed marginal differences with a p = .03). In addition, we obtained that the whole cerebellum volume shows evidences of sexual dimorphism which is consistent with (Tiemeier et al., 2010).

We observed that the whole cerebellum volume shows evidences of sexual dimorphism which is consistent with (Tiemeier et al., 2010). In addition, by using a segmentation protocol that divides the cerebellum in 12 structures, we provide specific results about sexual dimorphism (in absolute values) distinguishing lobules IV, V, VI, Crus I, VIIB, VIIIA, and VIIIB that significantly presented gender effect while the rest of lobules were not affected (Lobule IX showed marginal differences with a p = .03). Finally, none of the structures showed significant interaction between sex and age, either in absolute or normalized volumes.

Our results are also in partial agreement with (Fan et al., 2010) in which only absolute values presented significant differences across gender. Gray matter volume showed significant differences in lobules V, right Crus I, VII, VIIB, and left IX, in agreement with our findings. However, Fan's study did not show any significant differences for lobules IV, VI and VIIA while reported significant differences for Crus II in contrast with our results. These inconsistencies could be explained by the use of a different segmentation protocol, the age range limited to 18 and 33 years old and the size of the data set of 112 images.

The trajectories we generated showed different evolution patterns. Lobules III, IV, V, VI, Crus I, VIIB, VIIIA, VIIIB, and IX showed a fast growth in the early ages represented by an exponential cumulative distribution followed by a slow decrease that adjusted to a linear function or slightly curved second order model. Crus II described a curve instead of an inverted U‐shape that fitted a quadratic model after the fast growth. Finally, lobule X followed an inverted U‐shape represented by a cubic function without the presence of a fast growth stage. We observed a late peak maturation at 30 years old for VIIIB and lobule X, a slow volume increase until 40–50 years old as for hippocampus and amygdala (Coupe et al., 2017). Since the cerebellum is involved in learning and experience based‐plasticity, the delayed peak maturation of these structures may support the implication of these two subparts in lifespan adaptation abilities.

From the functional point of view, the anterior lobe (lobules I to V) is mainly involved in the well‐recognized sensorimotor function of the cerebellum (Stoodley & Schmahmann, 2009), and the developmental peak showed at about 12 and 16 years (in absolute values) is probably related with the maturation of the control of movement in kids. However, lobule V is somewhat distinct, having an ample peak during late adolescence, which in the relative trajectory translates into a plateau extending along the second and third lifespan decades. This suggests that lobule V may be the principal locus of the plasticity related to motor learning in early and middle adulthood. Several studies have shown that lobule V is associated with hand movements (Bushara et al., 2001; Grodd, Hulsmann, Lotze, Wildgruber, & Erb, 2001), including finger tapping (Stoodley et al., 2012), which is consistent with a role of this lobule in learning skilled hand movements.

The superior posterior lobe (our lobules VI and Crus I) is mainly related to cognitive functions, such as working memory and executive functions (motor planning and tool use) (Stoodley & Schmahmann, 2018), and these functionality is likely related with the connectivity of this lobe (mainly Crus I) with prefrontal cortical areas (Balsters, Whelan, Robertson, & Ramnani, 2013). Our results show that these lobules VI and Crus I have maturation peaks (in absolute values), slightly delayed with respect to that of the anterior lobe. This suggests that the maturation peak could be influenced by the later development of the prefrontal cortex (Teffer & Semendeferi, 2012).

With regard to the inferior posterior lobe (lobules Crus II, VIIB, VIIIA, VIIIB, and IX), it has been associated with a variety of cognitive performance (Stoodley & Schmahmann, 2018). However, there is heterogeneity in the roles in which the different lobules are involved. Lobule VIII is a secondary sensorimotor structure (Bushara et al., 2001; Debas et al., 2010), and in fact the trajectory we found for VIIIB is similar to that of lobule V, which is more involved in motor function. In contrast, Crus II, VIIB, and IX are the lobules with more strong interconnections with association cortices such as the prefrontal cortex (Kelly & Strick, 2003; O'Reilly et al., 2010), and in fact they show a trajectory similar (in absolute values) to that of lobules VI and Crus I (the superior posterior lobe).

The lobule X (or flocculonodular lobe) corresponds to the vestibulocerebellum, and is mainly involved in maintaining balance, posture and eye movements (Schniepp, Möhwald, & Wuehr, 2017). The lifespan trajectory we found is somewhat surprising, since for such basic functions it would be expected an early maturation in infancy and a long plateau along most of the lifespan. In contrast, we found a late maturation (around the third decade of life, in absolute values). This suggests maintained plasticity levels along the first four decades of life. Consistent with this hypothesis, experimental studies in animals have revealed the existence of long‐term potentiation and long‐term depression phenomena underlying motor learning in the vestibulo ocular reflex (Broussard, Titley, Antflick, & Hampson, 2011). Thus, it is possible that the functions of lobule X require a high level of plasticity along most of the lifespan.

Trajectories presented in (Han et al., 2020) are in agreement with our results. The anterior lobe (corresponding to lobules I, II, III, IV, and V) shows a slightly curved descending trajectory that perfectly accommodates with our lobules I, II, III, VI, and V trajectories between 55 and 90 years old for normalized volumes. The posterior lobe (corresponding to lobules VI, VIIA, VIIIA, VIIIB, Crus I, Crus II, and IX) presented a constant descending straight line. This is in contrast with our finding where lobules VI, VIIA, VIIIB, Crus II, and XI showed a descending curve begin lobules VIIIA and Crus I the only ones fitting a descending straight line. This differences could be explained by the averaging effect in in the posterior lobe where Lobule VIIIA and Crus I have a significant higher volume than the other lobules. Finally, lobule X presents as well a slightly curved descending trajectory similar to our lobule X trajectory which follow a slightly steeper descent. This slope difference can be explained as our models can benefit from a wider age range. Sexual dimorphism findings in (Han et al., 2020) are no comparable to our results as we are considering the whole lifespan while (Han et al., 2020) is only considering participants over 55 years old.

This study has some limitations. First, image resolution of 1 mm3 does not allow us to extract reliable conclusions about lobules I‐II (due to their small size) as it presents a linear trajectory close to constant. Image inhomogeneities affect cerebellum, especially the inferior lobules that can be mislabeled as CSF due to the signal loss. Fortunately, the N4 bias corrector can cope with most of the inhomogeneities and the rest of cases were removed from the study during the quality control. In addition, gathering several data sets can be a limitation due to the introduction of artificial differences. However, we used at least two overlapping data sets for each five periods and CERES preprocessing pipeline is designed to mitigate the negative impact of the use of different acquisition protocols.

Finally, as occurred in (Coupé et al., 2017), after the quality control we were left with no subjects younger than 9 months and the results over this period might be less accurate. As Coupé et al. explained in their work, very few studies are performed focusing on newborn since the acquisition is difficult and the low contrast before 6 months and the fast myelination progress during the first 2 years makes the analysis challenging.

5. CONCLUSION

In this work, we have performed a cerebellum volumetric analysis at structure and substructure scales covering the entire lifespan, using a very large number of subjects. We have addressed several limitations of previous studies and provided new knowledge about lobules cerebellum development and maturation. We used absolute and relative cerebellum volumes to better understand the cerebellum evolution in different stages for both males and females.

As a result, we provided robust models that represent the evolution of cerebellum lobules along the whole lifespan of the human cerebellum. These estimated models are very useful to clinical studies by providing normal boundaries of volumetric subparts of the cerebellum. In the near future, these models will be available through our online platform volBrain.

The data that support the findings of this study are available in corresponding websites previously listed in the materials and methods section.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Spanish DPI2017‐87743‐R grant from the Ministerio de Economia, Industria y Competitividad of Spain. This work benefited from the support of the project DeepvolBrain of the French National Research Agency (ANR‐18‐CE45‐0013). This study was achieved within the context of the Laboratory of Excellence TRAIL ANR‐10‐LABX‐57 for the BigDataBrain project. Moreover, we thank the Investments for the future Program IdEx Bordeaux (ANR‐10‐IDEX‐ 03‐ 02, HL‐MRI Project), Cluster of excellence CPU and the CNRS/INSERM for the DeepMultiBrain project.

In addition, we want to thank the investigators that collected and made available all the data in the data sets we used: The C‐MIND Data Repository created by the C‐MIND study of Normal Brain Development. Conducted by Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center and UCLA. https://research.cchmc.org/c-mind. The NDAR data were obtained from the NIH‐supported National Database for Autism Research (NDAR). NDAR is a collaborative informatics system created by the National Institutes of Health to provide a national resource to support and accelerate research in autism. Conducted by the Brain Development Cooperative Group. http://pediatricmri.nih.gov/nihpd/info/participating_centers.html. The ADNI data used were obtained from the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). The ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering and through generous contributions from the following: Abbott, AstraZeneca AB, Bayer Schering Pharma AG, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Eisai Global Clinical Development, Elan, Genentech, GE Healthcare, GlaxoSmithKline, Innogenetics NV, Johnson & Johnson, Eli Lilly and Co., Medpace, Inc., Merck and Co., Inc., Novartis, Pfizer Inc., F. Hoffmann‐La Roche, Schering‐Plough, Synarc Inc., as well as nonprofit partners, the Alzheimer's Association and Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation, with participation from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Private sector contributions to the ADNI are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study was coordinated by the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study at the University of California, San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for NeuroImaging at the University of California, Los Angeles. The OASIS1 data used were obtained from the OASIS1 project (http://www.oasis-brains.org/). The AIBL data used were obtained from the AIBL study of aging (www.aibl.csiro.au). The ICBM data used and the IXI data used were supported by http://www.brain-development.org/. The ABIDE data used were supported by ABIDE funding resources listed at http://fcon_1000.projects.nitrc.org/indi/abide/. ABIDE primary support for the work by Adriana Di Martino. Primary support for the work by Michael P. Milham and the INDI team was provided by gifts from Joseph P. Healy and the Stavros Niarchos Foundation to the Child Mind Institute. http://fcon_1000.projects.nitrc.org/indi/abide/. This manuscript reflects the views of the authors and may not reflect the opinions or views of the database providers.

Romero JE, Coupe P, Lanuza E, Catheline G, Manjón JV, Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Toward a unified analysis of cerebellum maturation and aging across the entire lifespan: A MRI analysis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2021;42:1287–1303. 10.1002/hbm.25293

Funding information Stavros Niarchos Foundation; University of California, Los Angeles; University of California, San Diego; Northern California Institute for Research and Education; Foundation for the National Institutes of Health; U.S. Food and Drug Administration; Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation; Alzheimer's Association; F. Hoffmann‐La Roche; Novartis; Johnson & Johnson; GE Healthcare; Elan; Bristol‐Myers Squibb; Bayer Schering; National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering; National Institute on Aging; Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative; National Institutes of Health; Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center; French National Research Agency, Grant/Award Number: CE45‐0013

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

C‐MIND (N = 266, after QC N = 182): The images from the C‐MIND dataset (https://research.cchmc.org/c‐mind/) used in this study consist of 266 control subjects. All the images were acquired at the same site on a 3T scanner. The MRI are 3D T1‐weighted MPRAGE high‐resolution anatomical scan of the entire brain with spatial resolution of 1 mm3 acquired using a 32 channel SENSE head‐coil. NDAR (N = 147, after QC N = 135): The Database for Autism Research (NDAR) is a national database funded by NIH (https://ndar.nih.gov). This database included 13 different cohorts acquired on 1.5T MRI and 3T scanners. In our study, we used 147 images of control subjects from the Lab Study 19 of National Database for Autism Research. For the NIHPD, T1‐weighted images were acquired at six different sites with 1.5 Tesla systems by General Electric (GE) and Siemens Medical Systems. The MRI are 3D T1‐weighted spoiled gradient recalled (SPGR) echo sequence with following parameters: TR = 22‐25 ms, TE = 10‐11 ms, flip angle = 30°, FoV = 256 mm IS × 256 mm AP, matrix size = 256 × 256: 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 voxels, 160‐180 slices of sagittal orientation. The participants chosen from the Lab Study 19 of National Database for Autism Research (NDAR) were scanned using a 3T Siemens Tim Trio scanner at each site. The MRI are 3D MPRAGE sequence (voxel dimensions: 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm3; image dimensions: 160 × 224 × 256, TE = 3.16 ms, TR = 2,400 ms). ABIDE (N = 528, after QC N = 450): The images from the Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE) dataset (http://fcon_1000.projects.nitrc.org/indi/abide/) used in this study consist of 528 control subjects acquired at 20 different sites on 3T scanner. The MRI are T1‐weight MPRAGE image and the details of acquisition, informed consent, and site‐specific protocols are available on the website. ICBM (N = 308, after QC N = 289): The images from the International Consortium for Brain Mapping (ICBM) dataset (http://www.loni.usc.edu/ICBM/) used in this study consist of 308 normal subjects obtained through the LONI website. The MRI are T1‐weighted MPRAGE (fast field echo, TR = 17 ms, TE = 10 ms, flip angle = 30°, 256 × 256 matrix, 1 mm2 in plane resolution, 1 mm thick slices) acquired on a 1.5T Philips GyroScan imaging system (Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands). OASIS1 (N = 315, after QC N = 290): The images from the Open Access Series of Imaging Studies (OASIS1) database (http://www.oasis‐brains.org) used in this study consist of 315 control subjects. The MRI are T1‐weighted MPRAGE image (TR = 9.7 ms, TE = 4 ms, TI = 20 ms, flip angle = 10 degrees, slice thickness = 1.25 mm, matrix size = 256 × 256, voxel dimensions = 1 × 1 × 1.25 mm3 resliced to 1 mm3, averages = 1) acquired on a 1.5‐T Vision scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). IXI (N = 588, after QC N = 519): The images from the Information eXtraction from Images (IXI) database (http://brain‐development.org/ixi‐dataset/) used in this study consist of 588 normal subjects. The MRI are T1weighted images collected at 3 sites with 1.5 and 3T scanners (FoV = 256 mm × 256 mm, matrix size = 0.9375 × 0.9375 × 1.2 mm3). ADNI1 (N = 228, after QC N = 218): The images from the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (http://adni.loni.usc.edu) used in this study consist of 228 control subjects from the 1.5T baseline collection. These images were acquired on 1.5T MR scanners at 60 different sites across the United States and Canada. A standardized MRI protocol to ensure cross‐site comparability was used. Typical MRI are 3D sagittal MPRAGE (repetition time (TR): 2,400 ms, minimum full TE, inversion time (TI): 1,000 ms, flip angle: 8°, 24 cm field of view, and a 192 × 192 × 166 acquisition matrix in the x‐, y‐, and z‐ dimensions, yielding a voxel size of 1.25 × 1.25 × 1.2 mm3, later reconstructed to get 1 mm3 isotropic voxel resolution). ADNI2 (N = 215, after QC N = 202): The images from the ADNI2 database (second phase of the ADNI project) consist of 215 control subjects. Images were acquired on 3T MR scanners with the standardized ADNI‐2 protocol, available online (www.loni.usc.edu). Typical MRI are T1‐weighted 3D MPRAGE sequence (repetition time 2,300 ms, echo time 2.98 ms, flip angle 9°, field of view 256 mm, resolution 1.1 × 1.1 × 1.2 mm3). AIBL (N = 236, after QC = 230): The Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) database (http://www.aibl.csiro.au/) used in this study consists of 236 control subjects. The imaging protocol was defined to follow ADNI's guideline on the 3T scanner (http://adni.loni.ucla.edu/research/protocols/mri‐protocols) and a custom MPRAGE sequence was used on the 1.5T scanner.

REFERENCES

- Asman, A. J. and Landman, B. A. (2012). Muti‐atlas segmentation using non‐local STAPLE. MICCAI Workshop on Multi‐Atlas Lebling, 87–90.

- Avants, B. B. , Tustison, N. , & Song, G. (2009). Advanced normalization tools (ANTS). Insight Journal. [Google Scholar]

- Badura, A. , Verpeut, J. L. , Metzger, J. W. , Pereira, T. D. , Pisano, T. J. , Deverett, B. , … Wang, S. S.‐H. (2018). Normal cognitive and social development require posterior cerebellar activity. eLife, 7, e36401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsters, J. H. , Whelan, C. D. , Robertson, I. H. , & Ramnani, N. (2013). Cerebellum and cognition: Evidence for the encoding of higher order rules. Cerebral Cortex, 23(6), 1433–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, C. , Shechtman, E. , Finkelstein, A. , & Goldman, D. B. (2009). PatchMatch: A randomized correspondence algorithm for structural image editing. ACM Transactions on Graphics, 28(3), 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, D. V. (2002). Cerebellar abnormalities in developmental dyslexia: cause, correlate or consequence? Cortex, 38, 491–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broussard, D. M. , Titley, H. K. , Antflick, J. , & Hampson, D. R. (2011). Motor learning in the VOR: The cerebellar component. Experimental Brain Research, 210, 451–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushara, K. , Wheat, J. , Khan, A. , Mock, B. J. , Turski, P. A. , Sorenson, J. , & Brooks, B. R. (2001). Multiple tactile maps in the human cerebellum. Neuroreport, 12, 2483–2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compston, A. , & Coles, A. (2008). Multiple sclerosis. Lancet, 372, 1502–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coupé, P. , Catheline, G. , Lanuza, E. , & Manjón, J. V. (2017). Towards a unified analysis of brain maturation and aging across the entire lifespan: A MRI analysis. Human Brain Mapping, 38, 5501–5518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coupé, P. , Manjón, J. V. , Fonov, V. , Pruessner, J. , Robles, M. , & Collins, D. L. (2011). Patch‐based segmentation using expert priors: Application to hippocampus and ventricle segmentation. NeuroImage, 54, 940–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courchesne, E. , Saitoh, O. , Yeung‐Courchesne, R. , Press, G. A. , Lincoln, A. J. , Haas, R. H. , & Schreibman, L. (1994). Abnormality of cerebellar vermian lobules VI and VII in patients with infantile autism: Identification of hypoplastic and hyperplastic subgroups with MR imaging. AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology, 162, 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davie, C. A. , Barker, G. J. , Webb, S. , Tofts, P. S. , Thompson, A. J. , Harding, A. E. , … Miller, D. H. (1995). Persistent functional deficit in multiple sclerosis and autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia is associated with axon loss. Brain, 6, 1583–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debas, K. , Carrier, J. , Orban, P. , Barakat, M. , Lungu, O. , Vandewalle, G. , … Doyon, J. (2010). Brain plasticity related to the consolidation of motor sequence learning and motor adaptation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(41), 17839–17844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond, J. E. , Gabrieli, J. D. E. , & Glover, G. H. (1998). Dissociation of frontal and cerebellar activity in a cognitive task: Evidence for a distinction between selection and search. NeuroImage, 7, 368–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, A. (2000). Close interrelation of motor development and cognitive development and of the cerebellum and prefrontal cortex. Child Development, 71, 44–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme, S. , Albaugh, M. D. , Nguyen, T. V. , Hudziak, J. J. , Mateos‐Perez, J. M. , Labbe, A. , … Brain Development Cooperative Group . (2016). Trajectories of cortical thickness maturation in normal brain development—The importance of quality control procedures. NeuroImage, 125, 267–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan, L. , Tang, Y. , Sun, B. , Gong, G. , Chen, Z. J. , Lin, X. , & Liu, S. (2010). Sexual dimorphism and asymmetry in human cerebellum: An MRI‐based morphometric study. Brain Research, 1353, 60–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraud, R. , Ta, V. T. , Papadakis, N. , Manjón, J. V. , Collins, D. L. , Coupé, P. , & Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . (2016). An optimized PatchMatch for multi‐scale and multi‐feature label fusion. NeuroImage, 124(A), 770–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grodd, W. , Hulsmann, E. , Lotze, M. , Wildgruber, D. , & Erb, M. (2001). Sensorimotor mapping of the human cerebellum: fMRI evidence of somatotopic organization. Human Brain Mapping, 13, 55–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guell, X. , Schmahmann, J. D. , Gabrieli, J. D. E. , & Ghosh, S. S. (2018). Functional gradients of the cerebellum. eLife, 7, e36652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habas, C. , Kamdar, N. , Nguyen, D. , Prater, K. , Beckmann, C. F. , Menon, V. , & Greicius, M. D. (2009). Distinct cerebellar contributions to intrinsic connectivity networks. The Journal of Neuroscience, 29(26), 8586–8594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, S. , An, Y. , Carass, A. , Prince, J. L. , & Resnick, S. M. (2020). Longitudinal analysis of regional cerebellum volumes during normal aging. NeuroImage, 220, 117062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James, A. C. , James, S. , Smith, D. M. , & Javaloyes, A. (2004). Cerebellar, prefrontal cortex, and thalamic volumes over two time points in adolescent‐onset schizophrenia. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 1023–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan, T. L. , Archibald, S. L. , Fennema‐Notestine, C. , Gamst, A. C. , Stout, J. C. , Bonner, J. , & Hesselink, J. R. (2001). Effects of age on tissues and regions of the cerebrum and cerebellum. Neurobiology of Aging, 22, 581–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kase, C. S. , Norrving, B. , Levine, S. R. , Babikian, V. L. , Chodosh, E. H. , Wolf, P. A. , & Welch, K. M. (1993). Cerebellar infarction. Clinical and anatomic observations in 66 cases. Stroke, 24, 76–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, R. M. , & Strick, P. L. (2003). Cerebellar loops with motor cortex and prefrontal cortex of a nonhuman primate. Journal of Neuroscience, 23(23), 8432–8444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klockgether, T. (2008). The clinical diagnosis of autosomal dominant. Cerebellum, 7, 101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krienen, F. M. , & Buckner, R. L. (2009). Segregated fronto‐cerebellar circuits revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity. Cerebral Cortex, 19(10), 2485–2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laidi, C. , Hajek, T. , Spaniel, F. , Kolenic, M. , d'Albis, M. , Sarrazin, S. , … Houenou, J. (2019). Cerebellar parcellation in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 140, 468–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel, C. , Gee, M. , Camicioli, R. , Wieler, M. , Martin, W. , & Beaulieu, C. (2012). Diffusion tensor imaging of white matter tract evolution over the lifespan. NeuroImage, 60, 340–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luft, A. R. , Skalej, M. , Schulz, J. B. , Welte, D. , Kolb, R. , Burk, K. , … Voight, K. (1999). Patterns of age‐related shrinkage in cerebellum and brainstem observed in vivo using three‐dimensional MRI volumetry. Cerebral Cortex, 9, 712–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makropoulos, A. , Aljabar, P. , Wright, R. , Huning, B. , Merchant, N. , Arichi, T. , … Rueckert, D. (2016). Regional growth and atlasing of the developing human brain. NeuroImage, 125, 456–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manjón, J. V. and Coupe, P. (2016). volBrain: An online MRI brain volumetry system. Frontiers in Neuroinformatics, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Manjon, J. V. , Eskildsen, S. F. , Coupe, P. , Romero, J. E. , Collins, D. L. , & Robles, M. (2014). Nonlocal intracranial cavity extraction. International Journal of Biomedical Imaging, 2014, 820205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manjón, J. V. , Tohka, J. , & Robles, M. (2010). Improved estimates of partial volume coefficients from noisy brain mri using spatial context. NeuroImage, 53, 480–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, F. A. , & Strick, P. L. (1997). Cerebellar output channels. International Review of Neurobiology, 41, 61–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroso, A. , Ruet, A. , Lamargue‐Hamel, D. , Munsch, F. , Deloire, M. , Coupé, P. , … Brochet, B. (2017). Posterior lobules of the cerebellum and information processing speed at various stages of multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 88, 146–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nenadic, I. , Sauer, H. , & Gaser, C. (2010). Distinct pattern of brain structural deficits in subsyndromes of schizophrenia delineated by psychopathology. Neuroimage, 49, 1153–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okugawa, G. , Sedvall, G. , Nordström, M. , Andreasen, N. , Pierson, R. , Magnotta, V. , & Agartz, I. (2002). Selective reduction of the posterior superior vermis in men with chronic schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 55, 61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly, J. X. , Beckmann, C. F. , Tomassini, V. , Ramnani, N. , & Johansen‐Berg, H. (2010). Distinct and overlapping functional zones in the cerebellum defined by resting state functional connectivity. Cerebral Cortex, 20(4), 953–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, M. T. M. , Pipitone, J. , Baer, L. H. , Winterburn, J. L. , Shah, Y. , Chavez, S. , … Chakravarty, M. M. (2014). Derivation of high‐resolution MRI atlases of the human cerebellum at 3T and segmentation using multiple automatically generated templates. NeuroImage, 95, 217–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poldrack, R. , & Gorgolewski, K. (2014). Making big data open: Data sharing in neuroimaging. Nature Neuroscience, 17, 1510–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramnani, N. (2006). The primate cortico‐cerebellar system: Anatomy and function. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 7, 511–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz, N. , Lindenberger, U. , Rodrigue, K. M. , Kennedy, K. M. , Head, D. , Williamson, A. , … Acker, J. D. (2005). Regional brain changes in aging healthy adults: General trends, individual differences, and modifiers. Cerebral Cortex, 15, 1676–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riva, D. , & Giorgi, C. (2000). The cerebellum contributes to higher functions during development: Evidence from a series of children surgically treated for posterior fossa tumours. Brain, 123(5), 1051–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero, J. E. , Coupé, P. , Giraud, R. , Ta, V. T. , Fonov, V. , Park, M. T. M. , … Manjón, J. V. (2017). CERES: A new cerebellum lobule segmentation method. NeuroImage, 47, 916–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmahmann, J. D. , & Sherman, J. C. (1998). The cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. Brain, 4, 121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schniepp, R. , Möhwald, K. , & Wuehr, M. (2017). Gait ataxia in humans: Vestibular and cerebellar control of dynamic stability. Journal of Neurology, 264, 87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman, L. J. , Valera, E. M. , & Makris, N. (2005). Structural brain imaging of attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 57, 1263–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoodley, C. J. (2016). The cerebellum and neurodevelopmental disorders. Cerebellum, 15(1), 34–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoodley, C. J. , & Schmahmann, J. D. (2009). Functional topography in the human cerebellum: A meta‐analysis of neuroimaging studies. NeuroImage, 44(2), 489–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoodley, C. J. , & Schmahmann, J. D. (2010). Evidence for topographic organization in the cerebellum of motor control versus cognitive and affective processing. Cortex, 46(7), 831–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoodley, C. J. , & Schmahmann, J. D. (2018). Chapter 4 ‐ functional topography of the human cerebellum. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 154, 59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoodley, C. J. , Valera, E. M. , & Schmahmann, J. D. (2012). Functional topography of the cerebellum for motor and cognitive tasks: An fMRI study. NeuroImage, 59(2), 1560–1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, E. V. , Brumback, T. , Tapert, S. F. , Brown, S. A. , Baker, F. C. , Colrain, I. M. , & Pohl, K. M. (2020). Disturbed cerebellar growth trajectories in adolescents who initiate alcohol drinking. Biological Psychiatry, 87(7), 632–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, E. V. , Deshmukh, A. , Desmond, J. E. , Lim, K. O. , & Pfefferbaum, A. (2000). Cerebellar volume decline in Normal aging, alcoholism, and Korsakoff's syndrome: Relation to ataxia. Neuropsychology, 14(3), 341–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ta, V. T. , Giraud, R. , Collins, D. L. , & Coupé, P. (2014). Optimized patchMatch for near real time and accurate label fusion. Medical Image Computing and Computer‐Assisted Intervention, 17, 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teffer, K. , & Semendeferi, K. (2012). Chapter 9 ‐ human prefrontal cortex: Evolution, development, and pathology. Progress in Brain Research, 195, 191–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomann, P. A. , Schläfer, C. , Seidi, U. , Santos, V. D. , Essig, M. , & Schröder, J. (2008). The cerebellum in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease ‐ A structural MRI study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 42, 1198–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiemeier, H. , Lenroot, R. K. , Greenstein, D. K. , Tran, L. , Pierson, R. , & Giedd, J. N. (2010). Cerebellum development during childhood and adolescence: A longitudinal morphometric MRI study. NeuroImage, 49(1), 63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tustison, N. J. , Avants, B. B. , Cook, P. A. , Zheng, Y. , Egan, A. , Yushkevich, P. A. , & Gee, J. C. (2010). N4ITK: Improved N3 bias correction. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 29(6), 1310–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walhovd, K. B. , Westlye, L. T. , Amlien, I. , Espeseth, T. , Reinvang, I. , Raz, N. , … Fjell, A. M. (2011). Consistent neuroanatomical age‐related volume differences across multiple samples. Neurobiology of Aging, 32, 916–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierenga, L. , Langen, M. , Ambrosino, S. , van Dijk, S. , Oranje, B. , & Durston, S. (2014). Typical development of basal ganglia, hippocampus, amygdala and cerebellum from age 7 to 24. NeuroImage, 96, 67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yushkevich, P. A. , Piven, J. , Hazlett, H. C. , Smith, R. G. , Ho, S. , Gee, J. C. , & Gerig, G. (2006). User‐guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: Significantly improved efficiency and reliability. NeuroImage, 31, 1116–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement