Abstract

Study Objectives:

To assess the performance of the single-channel automatic sleep staging (AS) software ASEEGA in adult patients diagnosed with various sleep disorders.

Methods:

Sleep recordings were included of 95 patients (38 women, 40.5 ± 13.7 years) diagnosed with insomnia (n = 23), idiopathic hypersomnia (n = 24), narcolepsy (n = 24), and obstructive sleep apnea (n = 24). Visual staging (VS) was performed by two experts (VS1 and VS2) according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine rules. AS was based on the analysis of a single electroencephalogram channel (Cz-Pz), without any information from electro-oculography nor electromyography. The epoch-by-epoch agreement (concordance and Conger’s coefficient [κ]) was compared pairwise (VS1-VS2, AS-VS1, AS-VS2) and between AS and consensual VS. Sleep parameters were also compared.

Results:

The pairwise agreements were: between AS and VS1, 78.6% (κ = 0.70); AS and VS2, 75.0% (0.65); and VS1 and VS2, 79.5% (0.72). Agreement between AS and consensual VS was 85.6% (0.80), with the following distribution: insomnia 85.5% (0.80), narcolepsy 83.8% (0.78), idiopathic hypersomnia 86.1% (0.68), and obstructive sleep disorder 87.2% (0.82). A significant low-amplitude scorer effect was observed for most sleep parameters, not always driven by the same scorer. Hypnograms obtained with AS and VS exhibited very close sleep organization, except for 80% of rapid eye movement sleep onset in the group diagnosed with narcolepsy missed by AS.

Conclusions:

Agreement between AS and VS in sleep disorders is comparable to that reported in healthy individuals and to interexpert agreement in patients. ASEEGA could therefore be considered as a complementary sleep stage scoring tool in clinical practice, after improvement of rapid eye movement sleep onset detection.

Citation:

Peter-Derex L, Berthomier C, Taillard J, et al. Automatic analysis of single-channel sleep EEG in a large spectrum of sleep disorders. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17(3):393–402.

Keywords: sleep staging, visual analysis, automatic analysis, scoring software, sleep pathology

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Diagnosis of many sleep disorders relies on polysomnography recordings that are visually interpreted. Sleep visual analysis is time-consuming and experience-dependent, and full polysomnography equipment is cumbersome and expensive, which justifies the search for reliable alternatives. The ASEEGA automatic sleep staging software is based on the analysis of a single electroencephalogram channel, already validated in healthy subjects. In this study, we evaluate its performance in a population of adult patients with various sleep disorders.

Study Impact: ASEEGA automatic sleep staging demonstrates high performances for sleep staging in various sleep disorders, including neurological hypersomnia, insomnia, and sleep apnea syndrome. These results allow consideration of the use of this software in clinical practice.

INTRODUCTION

Diagnosis of many sleep disorders, such as sleep apnea syndrome and hypersomnia, relies on polysomnography (PSG).1,2 Manual/visual PSG staging, based on analysis of several physiological signals, is usually performed by sleep physicians or technicians according to Rechtschaffen and Kales rules or American Association of Sleep Medicine (AASM) published international recommendations.3,4 However, the process of sleep stage scoring is time-consuming and requires long-term training.5 Moreover, the result of visual staging depends on the scorer’s experience. As with all human processes, visual staging is associated with subjective decisions, resulting in an inter-rater variability quantifiable by interscorer agreement (or disagreement) in sleep stage assignment.6 The inter-rater agreement ranges between 78% and 82%, with lower values (around 70%) in recordings of patients compared with healthy individuals.7–9 Finally, full PSG equipment is bulky and expensive, and technical realization of this exam is tedious, as it requires the placement of several sensors, at least electroencephalography (EEG), electro-oculography (EOG), and electromyography (EMG).

Thus, the search for automated alternatives to visual staging (VS) that need fewer parameters to discriminate sleep stages is relevant and various approaches have been proposed, mainly in healthy individuals.10 These methods can be classified into multi- or single-channel processing, and whether the classification method is based on Bayesian probabilities or artificial neural networks.10,11 They consist of three main steps: data preprocessing (to remove artifacts and amplify informative components), feature extraction and analysis (mainly time-frequency/nonlinear features), and classification that usually aims at mimicking the visual scoring rules.3,4 Development and evaluation of software dedicated to automatic sleep staging (AS) have to face several issues, among which are: (1) technical difficulties related to the complexity of EEG signal, to its interindividual variations, and to the fact that staging rules leave room for interpretation and are continuously evolving; (2) validation issues, as no perfect “gold standard” exists for sleep staging, so that evaluation of AS performance is indirect, based on comparison between AS-VS agreement and VS-VS agreement; (3) the population included, as the development of AS concerns not only basic science research (and therefore its use in healthy people) but also sleep studies for clinical trials and practice, ie, in pathological cases. In these cases, EEG interpretation is often more difficult, as sleep may be more disrupted, differentiation between sleep stages may be subtle, and drugs may modify sleep features. All these issues have to be solved before considering the use of automatic methods for sleep staging in clinical practice.

ASEEGA software (Physip, Paris, France) was developed in the 2000s.12,13 It is based on automated analysis of a single EEG channel using a combination of multiple signal processing and classification techniques. The preprocessing part aims notably at adapting the analysis criteria to cope with EEG interindividual variability. The analysis part uses both frequential and temporal techniques to retrieve numerous 30-second-long and 1-second-long features as well as performing the detection of several sleep microstructural events. The classification part then reduces and summarizes this information by scoring sleep EEG into conventional sleep stages using artificial intelligence techniques such as pattern recognition and fuzzy logic. The method was validated in healthy individuals and demonstrated high agreement with VS, between 82.9% and 96% according to the number of vigilance stages considered, allowing its use in several research studies.12,14–16

The aim of the present study was to evaluate ASEEGA performance in clinical practice in a wide population of patients who had been diagnosed with various sleep disorders, including central disorders of hypersomnolence, insomnia, and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSA).

METHODS

Study participants

A total of 95 patients (38 women, 40.4 ± 13 years) who had benefited from full-night PSG between 2009 and 2014 were retrospectively included in this study. Consecutive patients in each of the diagnostic groups were included. Diagnosis was based on clinical evaluation and PSG (± multiple sleep latency test ± 24-hour bedrest ± actigraphy) results, according to ICSD2 recommendations (used at the time of the study).17 Insomnia (n = 23, 12 women, 43.5 years ± 15.3) was defined by the primary complaint of difficulty initiating sleep and maintaining sleep, waking too early, or nonrestorative or poor quality sleep, despite adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep, and one or more complaints of daytime impairment (fatigue, cognitive impairment, mood disturbances, worries about sleep, etc) due to the sleep difficulty. All insomnia subtypes could be included in the study. Idiopathic hypersomnia (IH) (n = 24, 15 women, 36.3 years ± 11.2) was defined by excessive daytime sleepiness with either duration of the major sleep episode > 10 hours on PSG (IH with long sleep time) or a less-than-8-minute mean sleep latency on Multiple Sleep Latency Test and less than 2 sleep-onset REM sleep periods (SOREMP) (IH without long sleep time), without any other condition accounting for the symptoms. Among the included IH patients, 10 were classified as “IH with long sleep time.” Narcolepsy (n = 24, 6 women, 34.4 years ± 13.1) was defined as daily excessive daytime sleepiness for at least 3 months with or without cataplexy but with a Multiple Sleep Latency Test ≤ 8 minutes, at least 2 SOREMP, and no other medical disorder accounting for the symptoms. For narcolepsy with cataplexy, diagnosis could alternatively be confirmed by hypocretin cerebrospinal fluid levels ≤ 110 pg/ml. Among included patients, 15 had been diagnosed with narcolepsy with cataplexy. OSA patients (n = 24, 5 women, 48.1 years ± 10.9) had daytime or night-time symptoms (daytime sleepiness, fatigue, insomnia, snoring, etc), more than 15 respiratory events per hour of sleep, including apnea (≥ 90% airflow reduction, assessed by the nasal pressure signal, lasting ≥ 10 seconds) and hypopnea (≥ 30% airflow reduction, assessed by the nasal pressure signal, lasting ≥ 10 seconds, and associated with either an arousal or a ≥ 3% oxygen desaturation) with evidence of respiratory effort during all these events, and no other medical condition explaining the symptoms.

A total of 63% of patients were taking at least 1 treatment at the time of the PSG recording, among which antidepressants (15% of patients), anxiolytic or sedative drugs (6%), wake-promoting drugs (12%), analgesics (12%) antihypertensive drugs (20%), antidiabetic drugs (12%), lipid-lowering medication (12%), and 20% other drugs (anticoagulants, hormonal treatments, antiepileptic drugs, etc). Two patients were recorded while taking sodium oxybate. According to the French law on biomedical research conducted on retrospective data collected in a clinical context, patients were informed that their data could be used for research purposes and gave their consent for this use.

Recordings

Full-night PSG were conducted in the Sleep Unit of the Neurological Hospital of Lyon. Patients arrived in the late afternoon and underwent instrumentation for the electrodes and sensors required for PSG. The following signals were recorded: electroencephalogram (Fp2-C4; C4-T4; T4-O2; Fp1-C3; C3-T3; T4-O2; Fz-Cz; Cz-Pz), electro-oculogram, chin and tibialis electromyogram, electrocardiography, nasal airflow (nasal pressure and thermistor), pulse oximetry, and respiratory efforts (thoracic and abdominal belts). Recordings were performed using a Brain Spy 3100 (Micromed S.p.A., Treviso, Italy), sampling frequency = 128 Hz, band pass filter: [0.15–34] Hz, 40 dB/decade, 16 bits with an amplitude resolution of 97.6 nV/bit.

Manual sleep stage scoring

The 95 polysomnograms were scored independently by 2 sleep specialists (VS1 and VS2) from 2 different sleep laboratories: Sleep Unit of Neurological Hospital, Lyon (HB) and SANPSY, Bordeaux (JT). Sleep staging was based on AASM recommendations for identification of N1, N2, N3, rapid eye movement sleep (REM sleep), and wakefulness (W).4,18

Automatic analysis

The EEG bipolar channel Cz-Pz of each of the 95 recordings was automatically analyzed by ASEEGA (version R 3.33.10), using the same epoch-splitting as in the visual staging. The choice of the Cz-Pz channel was based on the fact that vertex sensors are usually well tolerated by patients, are less contaminated by muscle and ocular movement artifacts, and that Pz allows recording of posterior rhythms such as alpha oscillations. Analyses were also performed on the C4-O2 channel (AASM-recommended montage). Since there is no continuous learning process involved in the algorithm, all the recordings were subjected to exactly the same analysis. The analysis time was typically 5 minutes per recording.

Statistics

Automatic and visual stage scorings were first compared on a strict epoch-by-epoch basis. Three metrics of agreement were used. First, the percentage agreement, defined as the percentage of epochs that were assigned the same sleep stage. Second, Conger’s kappa coefficient (Conger’s κ), which is the generalization of the Cohen’s kappa coefficient (Cohen’s κ) to the comparison of more than 2 raters. In the case of 2 raters, Conger’s κ and Cohen’s κ are equivalent. In order to avoid the overweighting or underweighting of short or long nights, respectively, in the agreement computations, the comparisons were based on pooled night stage scorings rather than on averaged agreements over nights. Last, the sensitivity (probability that AS assigns the same sleep stage as did the staging reference) and positive predictive value (probability that the staging reference would have staged as AS did) were computed for each sleep stage. The corresponding specificities and negative predictive values were also provided.

In addition to the assessment of the global agreement, where the 3 stage scorings were considered as a pool whatever the scorer, automatic staging was assessed by comparison with 3 kinds of references: first, by pairwise comparisons against independent scorers VS1 and VS2, where epochs staged as artifacts or unstaged by AS were discarded; second, against the consensus of the 2 visual scorers, VSa = VS1 and VS2, where, in addition, epochs of disagreement between experts were discarded; and finally, against another way of merging visual stage scorings that consists in the inclusion of all expert decisions (VSo = VS1 or VS2). Using this reference, a comparison for a given epoch would match if AS assigns the same sleep stage as did at least 1 expert. The comparison covers all the recordings (overall comparison) before being applied separately per pathology.

Automatic and the 2 visual stage scorings were also compared in terms of sleep parameter estimates, namely sleep onset latency, wake after sleep onset (WASO), total sleep time, time spent in REM sleep, time spent in N3, time spent in N2, time spent in N1, sleep efficiency (total sleep time/time in bed × 100) (SE), REM sleep latency, and number of sleep stage changes. Given the variability and the heteroscedasticity of the parameters, the statistical analyses were carried out using linear mixed-effect models. We accounted for the interpatient variability by defining them as effects with random intercepts, thus instructing the model to correct for any systematic differences between these variabilities. Lmer of R lme4 package provides tools to analyze mixed effects of linear models.19 We analyzed the influence of 2 possible mixed effects: (1) the pathologies (4 levels: insomnia, hypersomnia, narcolepsy, and OSA) and (2) the scorers (3 levels: AS, VS1, and VS2). For each parameter, we fit a model on log-parameter values to better approximate normality. To perform type II analysis of variance, Wald chi-squared tests were used. Bland-Altman plots were also provided in order to better visualize and understand potential systematic bias. All P-values were corrected for multiple testing using a Bonferroni correction. For post-hoc tests, the emmeans package was used and P-values were considered as significant at P < .05 and adjusted for the number of comparisons performed using the Tukey method.20

RESULTS

Epoch-by-epoch comparison

Overall comparison

Among the 99,819 recorded epochs, 1,161 (1.2%) were discarded by AS for signal quality reasons on Cz-Pz, and 9 (0.01%) were unstaged by 1 expert before sleep onset, leaving 98,649 epochs for the statistical comparisons. For the global comparison between the 3 stage scorings κ was 0.69. Regarding the pairwise comparisons, agreements were 79.5% (κ = 0.72) between VS1 and VS2, 78.6% (κ = 0.70) between VS1 and AS, and 75.0% (κ = 0.65) between VS2 and AS. When considering only the 78,264 epochs of visual consensus, the agreement between AS and VSa was 85.6% (κ = 0.80). Finally, after reinjecting the epochs of visual disagreement and considering when AS agreed with at least 1 scorer, the agreement between AS and all expert decisions (VSo) was 85.6% (κ = 0.80).

Per pathology comparison

For the global comparison between the 3 stage scorings, κ did not differ between pathologies. It was 0.69 for the insomnia, hypersomnia, and OSA groups, and 0.68 for the narcolepsy group. Pairwise comparisons by pathology between AS, VS1, VS2, and VSa are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Agreement (%) and Conger’s coefficient (κ) between automatic sleep staging (AS) and visual staging (VS) according to sleep disorders.

| Sleep Disorders Agreement % (κ) | Pairwise Comparisons | Gold Standard |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | AS vs VS1 | AS vs VS2 | VS1 vs VS2 | AS vs VS1 and VS2 | |

| Insomnia | 23 | 78.9 (.71) | 74.6 (.65) | 79.4 (.72) | 85.5 (.80) |

| Hypersomnia | 24 | 79.8 (.71) | 76.2 (.65) | 81.0 (.72) | 86.1 (.79) |

| Narcolepsy | 24 | 77.2 (.69) | 72.6 (.63) | 79.6 (.73) | 83.8 (.78) |

| OSA | 24 | 78.4 (.70) | 76.5 (.67) | 77.4 (.69) | 87.2 (.82) |

The 5 stages (Wake, N1, N2, N3, and REM sleep) were considered. OSA = obstructive sleep apnea.

Per stage comparison

The contingency matrix of the AS-vs-VSa comparison is reported in Table 2. The highest consensus was observed for N2 and wake, and lowest consensus for N1. The sensitivities and positive predictive values for each sleep stage are reported in Table 3. The highest sensitivities were reached for N3, N2, and REM sleep and the higher positive predictive values were observed for N2 and wake. The lowest performance was found for N1.

Table 2.

Contingency matrix of the epoch-by-epoch comparison between automatic staging (AS) and visual staging consensus (VSa).

| Contingency Matrix (Number of Epochs) | Consensus of Visual stagings (VSa = VS1 and VS2) | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unscored or Experts Disagree | Wake | REM Sleep | N1 | N2 | N3 | ||

| Automatic staging (AS) | |||||||

| Artifact | 135 | 863 | 74 | 19 | 66 | 4 | 1,161 |

| Wake | 1,887 | 12,376 | 297 | 701 | 174 | 1 | 15,436 |

| REM sleep | 4,238 | 933 | 12,849 | 936 | 1,086 | 0 | 20,042 |

| N1 | 2,089 | 796 | 506 | 829 | 736 | 2 | 4,958 |

| N2 | 8,123 | 901 | 726 | 657 | 31,904 | 986 | 43,297 |

| N3 | 4,057 | 44 | 12 | 2 | 1,747 | 9,063 | 14,925 |

| Total | 20,529 | 15,913 | 14,464 | 3,144 | 35,713 | 10,056 | 99,819 |

Boldfaced values indicate agreement between AS and VS consensus.

Table 3.

Comparison between visual scoring consensus and autoscoring.

| Se (%) | Sp (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wake | 82.2 | 98.1 | 91.3 | 95.9 |

| REM sleep | 89.3 | 95.4 | 81.3 | 97.5 |

| N1 | 26.5 | 97.3 | 28.9 | 97.0 |

| N2 | 89.5 | 92.3 | 90.7 | 91.3 |

| N3 | 90.2 | 97.4 | 83.4 | 98.5 |

NPV = negative predictive value, PPV = positive predictive value, REM = rapid eye movement, Se = sensitivity, Sp = specificity.

Alternative EEG channel

The use of another channel (C4-O2) led to similar results with respect to interscorer agreements and scoring efficiency. Detailed results including sensitivity and positive predictive values are presented in Table S1 (741.3KB, pdf) in the supplemental material.

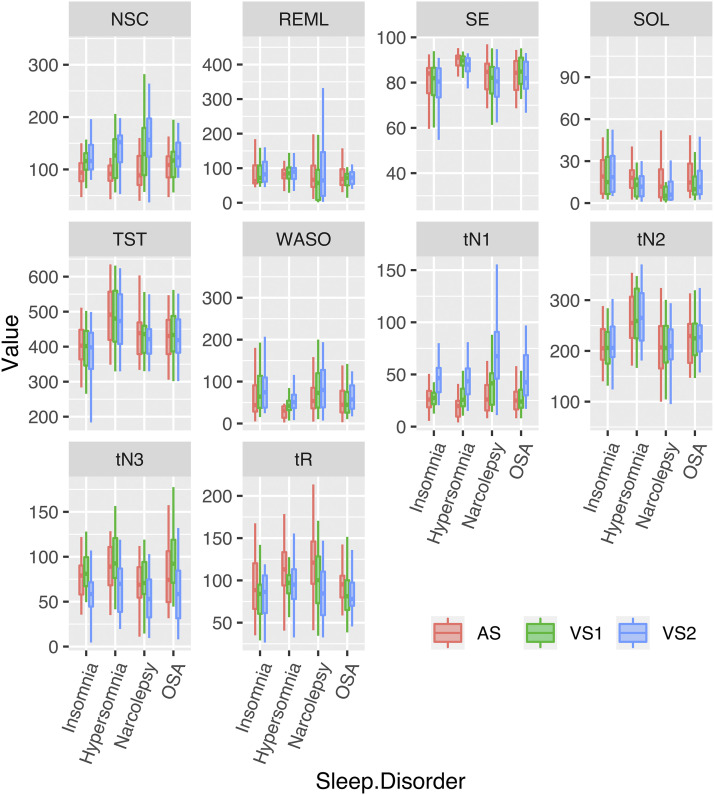

Sleep parameter comparison

Figure 1 summarizes the sleep parameter values for each scorer and each pathology (in the supplemental material, Table S2 (741.3KB, pdf) shows sleep parameters in the whole cohort of patients and Table S3 (741.3KB, pdf) shows sleep parameters in the whole cohort of patients per pathology). Analyses of variance revealed significant differences between VS1, VS2, and AS for all sleep parameters except for REM sleep latency. Depending on the pathology and sleep parameter, significant differences were driven by one or several scorers as specified, but interestingly not a single one in a systematic fashion. Post-hoc analysis revealed that total sleep time and sleep efficiency were significantly lower for VS2 than VS1 and AS, that sleep onset latency and time spent in REM sleep were significantly higher for AS than VS1 and VS2, and time spent in N3 was lower for VS2 than for VS1 and AS (and lower for AS than for VS1) (Table 4). A significant interaction between the sleep disorder (insomnia, IH, narcolepsy, or OSA) and the scorer (AS, VS1, VS2) was found for number of stage changes (P = .0008), WASO (P = .0228), and time spent in N1 (P = .0016). Post-hoc analyses revealed heterogeneous results depending on the sleep parameter and sleep disorder considered (Table 4). For number of stage changes, staging by VS1 and VS2 revealed a higher value than staging by AS for insomnia and hypersomnia, whereas staging by VS1 and AS differed from VS2 (higher values for VS2) for OSA, and the 3 stage scorings differed from another for narcolepsy. WASO was significantly lower as estimated by AS than by VS1 and VS2 for all sleep disorders except for OSA, where VS2 scored significantly more WASO than AS and VS1. Time spent in N1 was significantly higher when staged by VS2 than AS and VS1 for all sleep disorders, whereas in narcolepsy, staging results differed between the three scorers. In the supplemental material, detailed results of the above statistical analysis are given, and Bland and Altman plots are provided in Figure S1 (741.3KB, pdf) .

Figure 1. Sleep parameters according to the scorer and sleep disorder.

Representation of sleep parameter values (mean ± standard deviation, min-max) according to the scorer (red: automatic scoring [AS], green: visual staging 1 [VS1]; blue: visual staging 2 [VS2]) and to the sleep disorder (insomnia, idiopathic hypersomnia, narcolepsy, OSA). NSC = number of sleep stage changes, OSA = obstructive sleep apnea, REML = REM sleep latency, SE = sleep efficiency, SOL = sleep onset latency, TST = total sleep time, WASO = wake after sleep onset, tN1 = time in N1, tN2 = time in N2, tN3 = time in N3, tR = time in REM sleep.

Table 4.

Sleep parameter comparison.

| Sleep Parameters | No Interaction Scorer/Pathology | Interaction Scorer/Pathology Post-Hoc Analysis on Pathologies, Scorer Effect Driven by | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathology Effect | Scorer Effect (Driven by) | Interaction | Insomnia | Hypersomnia | Narcolepsy | OSA | |

| SOL | No | AS | — | — | — | — | — |

| WASO | — | — | P = .0228 | AS | AS | AS | VS2 |

| TST | Yes | VS2 | — | — | — | — | — |

| tN1 | — | — | P = .0016 | VS2 | VS2 | AS, VS1, VS2 | VS2 |

| tN2 | Yes | No | — | — | — | — | — |

| tN3 | Yes | AS, VS1, VS2 | — | — | — | — | — |

| tREM | No | AS | — | — | — | — | — |

| REML | No | No | — | — | — | — | — |

| SE | No | VS2 | — | — | — | — | — |

| NSC | — | — | P = .0008 | AS | AS | AS, VS1, VS2 | VS2 |

Results of the 2-way analysis of variance on log-parameter values, with scorers and pathologies as within and between subject factors, respectively. In case of interaction between scorers and pathologies, post-hoc tests were performed to further explain the observed differences between scorers according to the pathologies (detailed results are provided in the supplemental material). AS = automatic staging, NSC = number of sleep stage changes, OSA = obstructive sleep apnea, REML = REM sleep latency, SE = sleep efficiency, SOL = sleep onset latency, tN1 = time in N, tN2 = time in N2, tN3 = time in N3, tREM = time spent in REM sleep, TST = total sleep time, VS = visual staging, WASO = wake after sleep onset.

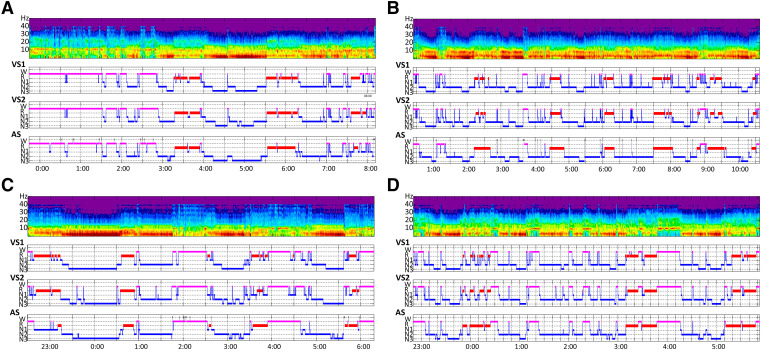

Qualitative comparison

Overall, qualitative comparison revealed that hypnograms obtained with VS and AS were very close in each patient group, despite a tendency toward a smoothing effect by AS in line with lower the number of stage changes as obtained with VS (Figure 2). However, even if REM sleep latency had not differed statistically between the 3 scorers in the whole population, in the narcolepsy diagnosis group 8 of 10 instances of REM sleep onset by VS1 were missed by AS, while 5 of 10 were detected by VS2. Other REM sleep episodes of the night were detected correctly in this group.

Figure 2. Four examples of patient with 4 plots each: from top to bottom time frequency analysis, hypnograms of visual scorers VS1 and VS2, and of ASEEGA automatic staging (AS).

(A) Patient with insomnia: global organizations of sleep are very similar between the visual scorers and AS. (B) Patient with idiopathic hypersomnia: in this example AS presented with less changes in sleep stages than VS, introducing a smoothing effect. (C) Patient with narcolepsy: AS did not detect the SOREMP. (D) Patient with OSA: typical organization of sleep with decrease of N3 and sleep fragmentation.

DISCUSSION

Our study reports for the first time a reliable automatic sleep stage scoring using single-channel analysis in various sleep disorders, including OSA, narcolepsy, IH, and insomnia. ASEEGA automatic sleep stage scoring reached 85.6% agreement with consensual VS in the whole cohort of patients and exhibited quite homogenous performances whichever sleep disorder is considered.

Numerous algorithms have been developed for semiautomatic/automatic sleep stage scoring since the pioneering work in the 70s.21,22 The performance of algorithms have improved over the years and most of them have achieved a satisfactory level of performance when tested on PSG recordings of healthy individuals (for review, see Fiorillo et al, 201923). However, the prospect of a clinical use, where the output of the analysis is intended to be a key input of a diagnostic procedure and the data are challenging, imposes stringent validation requirements and procedures. Our results are innovative because of (1) a population of patients with a wide range of sleep disorder diagnoses in which ASEEGA performance was evaluated, (2) the fact that no previous training in a wide database was needed, as the algorithm performed its analysis in a single-patient manner, adapting its staging criteria to each set of patient characteristics, and (3) the utilization of a single channel–based analysis.

The difficulty of sleep stage scoring in patients, especially in older ones taking drugs, is well known by physicians and technicians specialized in sleep medicine; their sleep is often more fragmented, with increased awakenings, includes less slow wave sleep, more sleep stage shifts, and perturbation of physiological microstructural features.24–26 Treatments, especially psychotropic drugs, can modify EEG and sleep structure, too.27,28 Most validation studies in the AS field select good-quality PSG recordings, whereas in clinical practice, technical issues are frequent. For all these reasons, the inter-rater agreement has been shown to be lower for patients’ than for healthy individuals’ recordings.9 Recently, Malafeev et al published a comparison of different algorithms using different signals (EEG alone or EEG+EOG+EMG) and reported overall high performance but heterogeneity regarding sleep stages and lower scores in patients (23 narcolepsy and 5 hypersomnia) compared with healthy participants.29 Such results stress the difficulties of sleep staging in patients. Validation of knowledge-based algorithms have been reported in patients diagnosed with OSA for the most part.30,31 More recently, artificial intelligence algorithms have been tested in other patient groups, such those diagnosed with insomnia, type 1 narcolepsy, restless leg syndrome, and periodic leg movements, but also Parkinson disease and cognitively-impaired and alcohol-treated patients.32–35 However, at the present time, very few automatic classification systems have reached a level of development compatible with clinical use, which implies a validation in normal individuals but also in patients with a high reliability and an easy utilization. Among them, the first commercial algorithm was the Morpheus sleep scoring system, developed by WideMed Ltd (Herzliya, Israel).36 It performs fully automated PSG data analysis that includes sleep stages, arousals and respiratory-event scoring, periodic leg movements and snoring detection, and ECG analysis. It has been validated in 31 study participants with suspected OSA; regarding 5-stage scoring, AS vs VS scoring agreement ranged from 73.3% to 77.7% (κ = 0.61–0.67) depending on the VS (2 scorers). The Somnolyzer 24-7 software proposed by the SIESTA group (Vienna, Austria) is based on the analysis of 1 central EEG channel, 2 EOG channels, and 1 chin EMG channel signals. It reached a level of agreement of 80% (Cohen’s κ = 0.72) compared to VS in a database of 277 recordings of adult patients diagnosed or not with sleep disorders (among which were OSA, Parkinson’s disease, and insomnia).37,38 Michele Sleep Scoring (Cerebra Medical Ltd, Winnipeg, Canada) developed by Younes et al is based on the analysis of central or frontal EEG channels.39 Its performance for the scoring of both sleep stages, arousals, and respiratory events has been evaluated mainly in healthy and OSA individuals but also in a few patients with neurological sleep disorders, with an agreement score ranging from 0.47 to 0.86 depending on the sleep stage considered.40 In the present study, we demonstrated high performance of ASEEGA, regarding percentage of agreement, sensitivity, and positive predictive values for each sleep stage, except stage N1, being the most ambiguous stage as previously reported.41 These performances are stable across 4 of the most common sleep disorders, representing the large majority of the activity of sleep labs. Our results also raise several issues regarding validation of AS algorithms in patients. In particular, whereas global performances remain high across patient groups, we find that interscorer epoch-by-epoch agreement is influenced by the pathology, which stresses the need for validation of AS software not only in OSA but also in various neurological sleep disorders. In most validation studies, however, pathologies have not or not sufficiently been identified in the dataset, and the agreement per pathology is not precisely documented.32,33 Our analyses of sleep parameters also reveal a significant scorer effect for almost all studied parameters, mainly of low amplitude but not always with the same cluster. This interexpert variability emphasizes the importance of using the confrontation of scorings performed by multiple scorers in AS algorithms evaluation, whereas some studies compare AS to one VS only, which exposes to the risk of overfitting this scoring, hence underfitting others.29,32 Including at least 2 scorings and building a more robust reference seems the appropriate way to address this issue. Although adding more scorings allows an increase in the robustness of the reference scoring,34,42 it also reduces the number of epochs included in the consensus scoring by excluding all difficult or ambiguous epochs where visual scorers disagree. The number of scorings included in a consensus should thus be considered in the interpretation of the indicators of agreement (percentage and κ).43

The second original aspect of our approach is that no database was required to train the system to a specific sleep disorder. Our study reflects real life sleep medicine practice: We included retrospectively, without any selection criteria regarding age, treatment, or technical quality, 95 PSG recordings of patients with various sleep disorder diagnoses and comorbidities (Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, depression, etc). More than 60% of our patients were taking medication at the time of the recording, among which more of one-third were psychotropic drugs. Whereas sleep scoring in these patients is often considered to be more difficult, this challenge did not decrease ASEEGA performance. Such results may be explained by the fact that ASEEGA adapts to the EEG behavior of the current recording to be analyzed without prior tuning or manual input. This is made possible by the use of classification rules that are flexible enough to adapt, for a given vigilance state, to various temporal and spectral contents according to the individuals or the sleep disorders involved. The development of these rules was an iterative process that addressed the EEG variability progressively by continually including additional recordings over time and adapted the classification rules accordingly. During this systematic setup phase, the purpose of the rule adaptation was to manage the new EEG content without decreasing the scoring performance on the existing database. A possible drawback of this capability to adapt the automated scoring rules to different behaviors may be that it allows such interindividual variability to tend to over-smooth the results, thus resulting in the above-mentioned lower number of sleep stage changes in AS compared to visual stage scoring. However, the ability of an AS software to adapt to each patient characteristic is crucial for considering its clinical use, as patient populations are not the same as “study populations,” and the necessity of selecting specific recordings and patients in which the algorithm can be used is not compatible with everyday practice.

Another strength of our study is the use of a single EEG channel for sleep classification. AS is all the more challenging as the number of signals processed is reduced. Comparisons of the performance of machine-learning algorithms according to the number of signals used by the algorithms (EEG alone or EEG+EOG+EMG) show that reducing the processed signals down to only 1 EEG alone entails a significant drop in performance for certain recordings and/or sleep stages.29,35 Only a few single-EEG channel algorithms have demonstrated validation in patients, mostly in OSA patients.30 Despite a reduced number of sensors, the ASEEGA algorithm reaches a level of performance at least equivalent to methods based on more, and more diversified, signals, equivalent on all 4 sleep disorders tested, and equivalent on data from healthy individuals and patients.12 The ability of the algorithm to differentiate vigilance states based only on EEG analysis is striking but echoes feedback from experienced scorers who report that they rely mostly on EEG, and suggests that all the needed information to score sleep is included in an EEG alone. Methods using only a single-EEG channel as input often perform worse, probably because sleep stage definition implies EOG and EMG characteristics, especially for REM sleep and sleep onset.3,18,44 Sleep onset latency was higher as detected by ASEEGA in our patients, and WASO was consequently lower, which highlights the difficulties of scoring transitional states. ASEEGA also showed its limits for SOREMP detection in patients diagnosed with narcolepsy. Abnormalities of REM sleep and of sleep stage transitions in narcolepsy may account for this finding.45 Even if a multiparameter (EEG+EOG+EMG)-based scoring appears to be more reliable, EMG signal can be misleading because some patients have a low muscle tone in wakefulness, others have a high muscle tone in REM sleep (as in REM sleep behavior disorders and narcolepsy), and because sometimes an EMG signal is of bad quality.46 From a practical point of view, reducing the number of sensors down to only 2 EEG sensors is an advantage as it reduces time and cost of the hook-up procedure and of data transfer in an e-health setting. With its sleep staging based on the analysis of a clinical grade EEG signal and otherwise fulfilling the technical requirements set forth by the AASM for accessibility to almost all PSG systems (sampling frequency of 200 Hz, no filters reducing the bandwidth except for the powerline filter, EDF format), ASEEGA is usable with existing PSG equipment and data. Full PSG datasets can be analyzed—only one EEG channel being processed in this case—as well as reduced montage limited to 1 EEG channel only. The hypnogram thus becomes available in clinical settings where it could be very helpful, for instance to improve the accuracy of the determination of the apnea-hypopnea index in a polygraphy framework by adding just 1 EEG channel providing sleep staging and thus determination of total sleep time.2,47 In the future, the implementation of arousals scoring may also allow an increase in sensitivity of hypopnea scoring.48

We have to acknowledge several limitations. Our study was retrospective and used recordings performed several years ago. Diagnosis criteria (according to ICSD) have evolved since 2015.49 However, the objective of the study was not to determine diagnosis value of ASEEGA for sleep disorders but to assess AS performance compared to VS in various clinical situations. Another limitation is linked to the fact that recordings were selected from the Lyon sleep database. Therefore, it is possible that VS1 (from Lyon) may have been influenced by reason of referral. More specifically, VS1 may have paid more attention to possible SOREMP (with potential over-scoring of SOREMP) in patients suspected of narcolepsy. On the contrary, VS2 may have considered SOREMP to be unlikely overall, which may have led to an under-scoring of SOREMP. The automatic scoring had no effect a priori on the probability of SOREMP occurrence, which may be considered as a strength for objective sleep scoring. ASEEGA analysis was performed on Cz-Pz, which is not a conventional channel according to the AASM procedure and scoring manuals. However, we do not believe that it influenced our results, as there is no evidence that the montage significantly influenced visual scoring, and as results obtained with ASEEGA in C4-O2 were close to those obtained with Cz-Pz.50 Even if Cz-Pz should be considered as the channel of choice for using ASEEGA, given its low contamination by artifacts, C4-O2 represents a reasonable alternative. In the absence of a control (healthy) group, we could not perform direct comparison of ASEEGA performance in healthy individuals and in patients, but ASEEGA has already been studied in nonpathological situations.12 As there is no optimal gold standard sleep scoring, ASEEGA was here compared with VS performed by 2 scorers; a greater number of scorers would have increased the accuracy of sleep scoring, as discussed previously. Nevertheless, the fact that scorers came from different institutions allowed us to avoid a “center” effect. Few epochs were removed from the performance analysis as they were discarded by AS for signal quality reasons. We do not believe that this approach, shared by other groups in several validation studies, significantly influenced our results given the low proportion of excluded epochs (1.2%).8 Our study focused on sleep staging, which is the first step in sleep recordings analysis. Since then, we have implemented detection of events (arousals) for evaluation in the patient population. Finally, this retrospective study was an “off-label” use of the algorithm, since its recording specifications were not met in terms of sampling frequency (Fs = 128Hz < minimum required of 200 Hz) and therefore in terms of low-pass filtering (Fc = 34 Hz < minimum required of 80 Hz). The consequences of this loss of information regarding the high frequencies are not easy to quantify in terms of classification, because it depends on the spectral content of each recording. It can be assumed that the vigilance states with high-frequency content, wake, and REM sleep might have been impacted in some cases.

CONCLUSIONS

ASEEGA performance in patients presenting with various sleep disorders reaches values obtained in healthy individuals. The high performance of a single-channel analysis for sleep stage discrimination challenges our understanding of sleep and highlights the importance of a close cooperation between engineers, researchers, and practitioners in the development of AS systems. The integration of AS algorithms in existing recording PSG devices may allow consideration of their utilization in clinical practice for sleep scoring, provided that there is reflection at the same time on the many obstacles, from regulatory requirements to professional evolving practices, to automatic scoring software adoption.23 The implementation of automated analysis could be an opportunity to address the major challenges that sleep medicine is and will be facing in terms of number of patients, quality of care, and sustainability of costs.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

All authors have seen and approved the manuscript. Work for this study was done at the authors’ respective institutions. C. Berthomier, P. Berthomier, and M. Brandewinder have ownership and directorship in Physip and are employees of Physip, which owns ASEEGA. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank to Dr. O. Benoit, MD, PhD, and J. Prado, PhD, for their helpful scientific and technical discussions at the early stages of this study.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AS

automatic sleep staging

- EEG

electroencephalography

- EMG

electromyography

- EOG

electro-oculography

- IH

idiopathic hypersomnia

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

- PSG

polysomnography

- REM sleep

rapid eye movement sleep

- SOREMP

sleep onset REM period

- VS

visual staging

- VSa

consensus of 2 visual scorers

- WASO

wake after sleep onset

REFERENCES

- 1.Fischer J, Dogas Z, Bassetti CL, et al.; Executive Committee (EC) of the Assembly of the National Sleep Societies (ANSS) ; Board of the European Sleep Research Society (ESRS), Regensburg, Germany . Standard procedures for adults in accredited sleep medicine centres in Europe. J Sleep Res. 2012;21(4):357–368. 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2011.00987.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kapur VK, Auckley DH, Chowdhuri S, et al. Clinical practice guideline for diagnostic testing for adult obstructive sleep apnea: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(3):479–504. 10.5664/jcsm.6506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A (eds). A Manual of Standardized Terminology, Techniques and Scoring System For Sleep Stage of Human Subjects. Bethesda, MD: US National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Blindness, Neurological Information Network; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry RB, Brooks R, Gamaldo CE, et al. ; for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine . The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. Version 2.4. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chediak A, Esparis B, Isaacson R, et al. How many polysomnograms must sleep fellows score before becoming proficient at scoring sleep? J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2(4):427–430. 10.5664/jcsm.26659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Penzel T, Zhang X, Fietze I. Inter-scorer reliability between sleep centers can teach us what to improve in the scoring rules. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(1):89–91. 10.5664/jcsm.2352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Younes M, Raneri J, Hanly P. Staging sleep in polysomnograms: analysis of inter-scorer variability. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(6):885–894. 10.5664/jcsm.5894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danker-Hopfe H, Anderer P, Zeitlhofer J, et al. Interrater reliability for sleep scoring according to the Rechtschaffen & Kales and the new AASM standard. J Sleep Res. 2009;18(1):74–84. 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00700.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Norman RG, Pal I, Stewart C, Walsleben JA, Rapoport DM. Interobserver agreement among sleep scorers from different centers in a large dataset. Sleep. 2000;23(7):901–908. 10.1093/sleep/23.7.1e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boostani R, Karimzadeh F, Nami M. A comparative review on sleep stage classification methods in patients and healthy individuals. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2017;140:77–91. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2016.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ronzhina M, Janoušek O, Kolářová J, Nováková M, Honzík P, Provazník I. Sleep scoring using artificial neural networks. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16(3):251–263. 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berthomier C, Drouot X, Herman-Stoïca M, et al. Automatic analysis of single-channel sleep EEG: validation in healthy individuals. Sleep. 2007;30(11):1587–1595. 10.1093/sleep/30.11.1587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berthomier C, Prado J, Benoit O. Automatic sleep EEG analysis using filter banks. Biomed Sci Instrum. 1999;35:241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dang-Vu TT, Hatch B, Salimi A, et al. Sleep spindles may predict response to cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia. Sleep Med. 2017;39:54–61. 10.1016/j.sleep.2017.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maire M, Reichert CF, Gabel V, et al. Human brain patterns underlying vigilant attention: impact of sleep debt, circadian phase and attentional engagement. Sci Rep 2018;8:970. 10.1038/s41598-017-17022-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaggioni G, Ly JQM, Muto V, et al. Age-related decrease in cortical excitability circadian variations during sleep loss and its links with cognition. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;78:52–63. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Academy of Sleep Medicine . International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic and Coding Manual. 2nd ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson AL Jr, Quan SF; for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine . The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. 1st ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67(1). 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lenth R, Buerkner P, Herve M, Love J, Riebl H, Singmann H. emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. R package version 1.4.1. The Comprehensive R Archive Network. Available from: https://github.com/rvlenth/emmeans. Accessed October 24, 2020. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Itil TM, Shapiro DM, Fink M, Kassebaum D. Digital computer classifications of EEG sleep stages. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1969;27(1):76–83. 10.1016/0013-4694(69)90112-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith JR, Karacan I. EEG sleep stage scoring by an automatic hybrid system. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1971;31(3):231–237. 10.1016/0013-4694(71)90092-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiorillo L, Puiatti A, Papandrea M, et al. Automated sleep scoring: A review of the latest approaches. Sleep Med Rev. 2019;48:101204. 10.1016/j.smrv.2019.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roth T, Dauvilliers Y, Mignot E, Montplaisir J, Paul J, Swick T, Zee P. Disrupted nighttime sleep in narcolepsy. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(9):955–965. 10.5664/jcsm.3004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bliwise DL. Sleep in normal aging and dementia. Sleep. 1993;16(1):40–81. 10.1093/sleep/16.1.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lusic Kalcina L, Valic M, Pecotic R, Pavlinac Dodig I, Dogas Z. Good and poor sleepers among OSA patients: sleep quality and overnight polysomnography findings. Neurol Sci. 2017;38(7):1299–1306. 10.1007/s10072-017-2978-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wichniak A, Wierzbicka A, Walęcka M, Jernajczyk W. Effects of Antidepressants on Sleep. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(9):63. 10.1007/s11920-017-0816-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borbély AA, Mattmann P, Loepfe M, Strauch I, Lehmann D. Effect of benzodiazepine hypnotics on all-night sleep EEG spectra. Hum Neurobiol. 1985;4(3):189–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malafeev A, Laptev D, Bauer S, et al. Automatic human sleep stage scoring using deep neural networks. Front Neurosci. 2018. 10.3389/fnins.2018.00781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stepnowsky C, Levendowski D, Popovic D, Ayappa I, Rapoport DM. Scoring accuracy of automated sleep staging from a bipolar electroocular recording compared to manual scoring by multiple raters. Sleep Med. 2013;14(11):1199–1207. 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park DY, Kim HJ, Kim CH, et al. Reliability and validity testing of automated scoring in obstructive sleep apnea diagnosis with the Embletta X100. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(2):493–497. 10.1002/lary.24878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patanaik A, Ong JL, Gooley JJ, Ancoli-Israel S, Chee MWL. An end-to-end framework for real-time automatic sleep stage classification. Sleep. 2018;41(5):zsy04. 10.1093/sleep/zsy041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biswal S, Sun H, Goparaju B, Westover MB, Sun J, Bianchi MT. Expert-level sleep scoring with deep neural networks. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(12):1643–1650. 10.1093/jamia/ocy131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stephansen JB, Olesen AN, Olsen M, et al. Neural network analysis of sleep stages enables efficient diagnosis of narcolepsy. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):5229. 10.1038/s41467-018-07229-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allocca G, Ma S, Martelli D, et al. Validation of ‘Somnivore’, a machine learning algorithm for automated scoring and analysis of polysomnography data. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:207. 10.3389/fnins.2019.00207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pittman SD, MacDonald MM, Fogel RB, et al. Assessment of automated scoring of polysomnographic recordings in a population with suspected sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep. 2004;27(7):1394–1403. 10.1093/sleep/27.7.1394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klosch G, Kemp B, Penzel T, et al. The SIESTA project polygraphic and clinical database. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag. 2001;20(3):51–57. 10.1109/51.932725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderer P, Gruber G, Parapatics S, et al. An E-health solution for automatic sleep classification according to Rechtschaffen and Kales: validation study of the Somnolyzer 24 x 7 utilizing the Siesta database. Neuropsychobiology. 2005;51(3):115–133. 10.1159/000085205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Younes M, Younes M, Giannouli E. Accuracy of Automatic Polysomnography Scoring Using Frontal Electrodes. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(5):735–746. 10.5664/jcsm.5808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuna ST, Benca R, Kushida CA, et al. Agreement in computer-assisted manual scoring of polysomnograms across sleep centers. Sleep. 2013;36(4):583–589. 10.5665/sleep.2550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenberg RS, Van Hout S. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine inter-scorer reliability program: sleep stage scoring. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(1):81–87. 10.5664/jcsm.2350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Younes M, Hanly PJ. Minimizing Interrater Variability in Staging Sleep by Use of Computer-Derived Features. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(10):1347–1356. 10.5664/jcsm.6186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berthomier C, Muto V, Schmidt C, et al. Exploring scoring methods for research studies: accuracy and variability of visual and automated sleep scoring. J Sleep Res. 2020;29(5):e12994. 10.1111/jsr.12994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Phan H, Andreotti F, Cooray N, Chén OY, De Vos M. Joint Classification and Prediction CNN Framework for Automatic Sleep Stage Classification. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2019;66(5):1285–1296. 10.1109/TBME.2018.2872652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mukai J, Uchida S, Miyazaki S, Nishihara K, Honda Y. Spectral analysis of all-night human sleep EEG in narcoleptic patients and normal subjects. J Sleep Res. 2003;12(1):63–71. 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2003.00331.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khalil A, Wright MA, Walker MC, Eriksson SH. Loss of rapid eye movement sleep atonia in patients with REM sleep behavioral disorder, narcolepsy, and isolated loss of REM atonia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9(10):1039–1048. 10.5664/jcsm.3078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sabil A, Vanbuis J, Baffet G, et al. Automatic identification of sleep and wakefulness using single-channel EEG and respiratory polygraphy signals for the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea. J Sleep Res. 2019;28(2):e12795. 10.1111/jsr.12795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malhotra RK, Kirsch DB, Kristo DA, et al. American Academy of Sleep Medicine Board of Directors . Polysomnography for obstructive sleep apnea should include arousal-based scoring: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine position statement. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(7):1245–1247. 10.5664/jcsm.7234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 3rd ed. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Duce B, Rego C, Milosavljevic J, Hukins C. The AASM recommended and acceptable EEG montages are comparable for the staging of sleep and scoring of EEG arousals. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(7):803–809. 10.5664/jcsm.3880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.