Abstract

During the Middle Ages, Parma, in Northern Italy, undoubtedly represented a landmark for surgical science and practice all around Europe. Around the same period the Salernitan Medical School, already famous since the high Middle Ages, reached its whole scientific role. Due to the importance reached by the School, for centuries several physicians throughout Europe, aiming for an international fame, told they were “Salernitan”. One of the most famous examples is represented by Roger Frugardi, or Ruggero Frugardo, or Ruggero da Parma (before 1140 – about 1195), who was widely known as “Rogerius Salernitanus” (Roger of Salerno), meaning that his scientific success was a consequence of the affiliation to the Salernitan Medical School. Roger wrote an important book, the “Practica Chirurgiae” (Surgical Practice), also known as “Rogerina”, edited and published by his pupil Guido “the young” of Arezzo. It was the first Handbook of Surgery in the post-Latin Europe, containing important innovations, such as the very first description of a thyroidectomy, thus influencing surgical practice until late Renaissance. The Roger’s pupil Rolando dei Capelluti was the successor and extensor of his Master’s work. In his work he particularly developed the cranial surgery and the study of neurological diseases (e.g., epilepsy or mania). His masterwork, known as “Rolandina”, also influenced European surgery for centuries. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: Roger Frugardi, Roger of Parma, Rolando dei Capelluti, Roland of Parma, Practica Chirurgiae, Surgery in the Middle Ages

Introduction

During the Middle Ages, Parma, in Northern Italy, undoubtedly represented a landmark for surgical science and practice all around Europe. The roots of this magnificence must, however, be searched elsewhere, and precisely in Salerno. Here there was the Salernitan Medical School, already famous since the high Middle Ages. This School reached its whole scientific role between the 11th and 12th Centuries, then declining later, due to the rising of modern universities (1,2).

The Salernitan Medical School, was mainly funded on a Langobardic basis (3), since this city fell under Langobardic domination in the year 847, after the collapse of the Northern Italy Langobardic kingdom (4). Langobards gave a powerful speed up to the development of Salernitan culture, mainly acting as a vehicle for Greek and Arabic knowledge (5).

Due to the importance reached by the Salernitan Medical School, for centuries several physicians throughout Europe, aiming for an international fame, told they were “Salernitan”.

The Masters

For sure, one of the most famous examples is represented by Roger Frugardi, or Ruggero Frugardo, or Ruggero da Parma (before 1140 – about 1195): probably because of the aforementioned reasons, he was widely known as “Rogerius Salernitanus” (Roger of Salerno), to meaning that his scientific success was a consequence of the affiliation to the Salernitan Medical School. He was, however, actually Scandinavian, coming from Frugård (Finland). When he was a child, in the year 1154 he moved to Parma, where his father was based following the Emperor Frederyk I, the “Barbarossa” (6). Information on his life is substantially poor and we do not know if he has never been student in Salerno. Roger worked in the already existing Parmesan School of Surgery, gaining growing prestige and finally becoming a Master of it (6).

We have, however, plenty information on his work in Parma through two of his pupils. The first was Guido “the young” of Arezzo (that must be distinguished from the older Guido of Arezzo, 991/992 – after 1033, the Benedictine monk that was the inventor of musical notation, or staff notation, that replaced the ancient neumatic notation). (7). He was the editor and publisher of Roger’s work. The second was Rolando dei Capelluti, who worked at reviewing and completing the teacher’s work.

Roger, indeed, wrote an important book, the “Practica Chirurgiae” (Surgical Practice), also known as “Compendium Chirurgiae”, “Post Mundi Fabricam”, “Cyrurgia”, or “Rogerina”, edited and published in 1180 by Guido “the young” of Arezzo (6). It was the first Handbook of Surgery in the post-Latin Europe, paving the way for further western surgical manuals, thus influencing the surgical practice until late Renaissance. It is highly structured, presenting the problems in a pathologic-traumatological systematization. It is divided in 4 books, accounting for 127 chapters. The first book (44 chapters) concerns head affections, the second (16 chapters) concerns diseases and traumas of neck and throat, the third (50 chapters) deals with chest and abdomen problems, whilst the fourth (17 chapters) faces limbs diseases and traumas, and also several matters of general interest. The largest part of the textbook is involved in traumatology, but several encroachments in non-traumatic diseases are present (8).

Interestingly, before any description of a surgical procedure, he reported a rich pharmacopeia, showing the willingness to heal the patients in a bloodless way, avoiding surgery, that was, at those times, highly painful and risky (8).

Still remarkable are some descriptions. For example, citing the exploration of a scalp wound he wrote: «The finger must be introduced into the wound, then you should carefully explore, since no way better than finger touch does exist to recognize a skull fracture». Furthermore, describing the suture of a wound, he says: «The suture should be made with separate stitches, with a square-shaped needle, leaving one of the extremities open to introduce a drainage in it» (8).

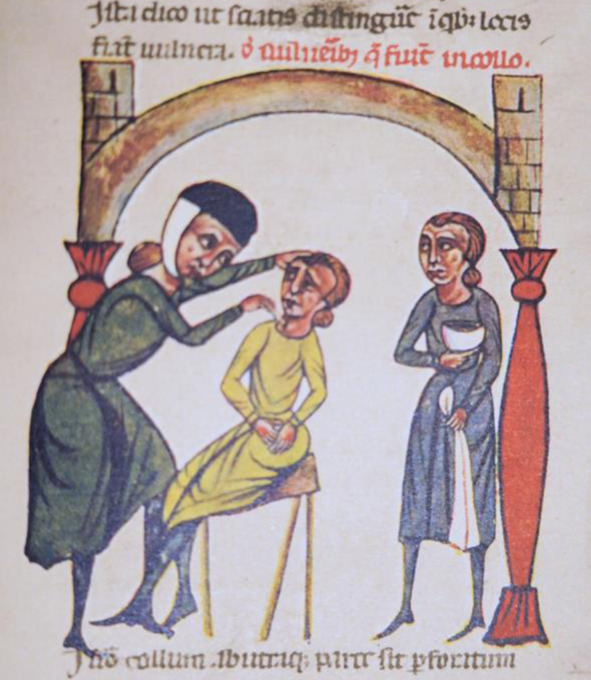

Particularly noteworthy is the complete description, absolutely astonishing in his times, of a thyroidectomy for goiter (Fig. 1) (9). This idea was so ahead of his time that it was rediscovered only about 700 years later by Guillaume Dupuytren, chief surgeon of the Hôtel-Dieu Hospital in Paris. This eminent scientist operated Napoleon Bonaparte of hemorrhoids and is universally renowned for his description of Dupuytren’s contracture, which he first operated in 1831, also publishing his experience in The Lancet (10). Dupuytren described the technique of thyroidectomy, closely resembling the description of Roger, in an article also published in The Lancet (11).

Figure 1.

Surgery for goiter, according to Roger Frugardi

Another important indication contained in the “Practica Chirurgiae” deals with the opportunity to put the patient in an anti-declivous position (Trendelemburg position, or rather Roger position?) in case of severe abdominal wounds (Fig. 2) (8,12).

Figure 2.

Anti-shock position, generally known as Trendelemburg position, as firstly described by Roger Frugardi

Among many others, Roger wrote a sentence that seems to forestall the now sadly famous “defensive medicine”. In case of wounds involving heart, lung, liver or stomach, his recommendation is, indeed, the following: «To avoid that patient’s death could be ascribed to our operation, it would be better to refuse the task» (8).

Roger was an independent observer, poorly influenced by the ancient “magistri”. He also was the first to use the term “lupus” to describe the classic malar rash (6).

It is quite certain that the inspirer of Roger was the ancient byzantine surgeon Paul of Aegina, active in the Byzantine Empire during the VII Century. Paul can be considered as the encoder and reviser of the whole body of scientific knowledge of the ancient times. His work was for sure known in Salerno, since it was here translated from Greek by the Montecassino’s monks (13,14).

We should recognize that in the same period, i.e., across the XI and XII Centuries, there was another important surgical school in Cordoba, Spain. The Master of this school was the Arab physician and surgeon Albucasi (Abu El Qasim). He wrote the “Kitab al Tasrif”, a Medical Encyclopedia consisting in 30 books, the 30th of which is totally devoted to surgery. Albucasi was also inspired by the work of Paul of Aegina, well known in the Hispano-Arabic cultural milieu (15). Roger could not know the Albucasi’s work, since the first Latin translation of this textbook was made in Toledo, by Gherardo da Cremona, in the year 1181, thus one year after the first publication of Roger’s “Practica Chirurgiae” (16).

Maybe the main shadow in Roger’s work was the persisting conviction that suppuration is the best way to obtain the healing of a wound, according to the Hippocratic and Galenic concept of “pus bonum et laudabile” (pus good and praiseworthy) (6). This concept, lasting for about one and a half millennium, was definitely challenged by the Italian surgeon Teodorico Borgognoni (1205-1296) and by the French surgeons Henri de Mondeville (1260-1320) and Guy de Chauliac (1300-1368). They bravely defied the Authority of the ancient Greeks (17).

As previously noted, the Roger’s pupil Rolando dei Capelluti (or Rolando Capelluti, or Rolando [dei] Capezzuti) was the successor and extensor of his Master’s work. If possible, his life is at least as mysterious as the Roger’s one. Even his name is not for sure the generally known one. Rolandus Parmensis (Roland of Parma), as he was known in his time, was born in Parma probably in the year 1198 and died in Bologna in the period between the years 1280 and 1286. The surname “Capellutus” is mentioned for the first time in the codex 1065 of the XV Century, treasured in the “Palatina” Library of Parma, probably written by the Parmesan physician Rolando Capelluti “the Young” with the aim to give an illustrious ancestry to his family (18). Rolando was the first doctor registered in the recently established College of doctors of Parma. The “colleges”, often also called with the attribute of “noble”, judged whether a doctor could practice within the city. Moreover, when University Studium, although not an academic structure, was present, they were allowed to take part of the commissions for the exams, degrees and licenses (for example for surgeons who did not need a medical degree). They also had a censorship function on members until canceled. The oldest information on the College of Parma are recorded in a manuscript preserved in the “Palatine” Library of Parma (Manuscript of Parma 1532) of the year 1440. The first names of the respective lists are written by the same hand because they were copied from a previous book, probably the original one of the year 1294. Doctors and surgeons are called “magistri” (masters), but the earliests are also referred to as “domini” (gentlemen). The first name on the list is Magister Rolandus de Capellutis Cyrugicus, i.e. Roland of Parma. Interestingly, in the list of surgeons of the first 150 years, his name is followed by five “domini” with the same surname, and also by the homonymous Rolando Capelluti “the Young”, just mentioned. It should be noted that in 1294 Roland was already dead, but starting the list of the College with his name was an opportunity to ennoble the whole category (19,20).

In those centuries no surgical books were published, as the same Roland states: «Medicina multi fuerunt libri conditi a plurimis, de chyrurgia nulli vel pauci» (Several books of medicine have been written, but surgical books are very rare, if any) (21).

As such, a few years after the publication of Roger’s “Practica Chirurgiae”, Roland edited a new extended version of the work of his master. This new textbook, entitled “Glossulae quatuor magistrorum super chirurgiam Rogerii et Rolandi” (Commentaries from four Masters on the surgery of Roger and Rolando), or “Rolandina” (from his own name, likewise the “Rogerina”), containing several “addictiones” (addenda or glosses), sometimes only explicative, but often supplementary, to the original manuscript (22). The date of the first edition is unknown and the work is firstly mentioned in the codex 7035 of the XIII Century, preserved in the Bibliothèque Nationale de Paris (23).

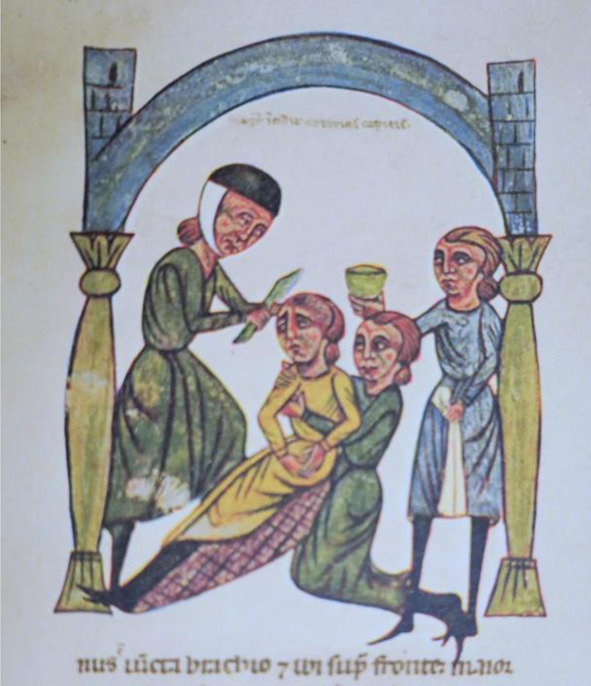

The “Rolandina”, likewise the “Rogerina”, is also divided in four books, although with a different distribution. The first book describes diseases and traumas of the head, with chapters describing methods of care for melancholy, epilepsy and several eyes, nose and ears sicknesses. The second book deals with wounds of neck and chest. The third book takes into consideration the fractures and wounds of upper limbs, various diseases of the abdomen, breast cancer, hernias and bladder stones. Finally, the fourth book describes fractures and wounds of lower limbs, as well as sciatica and arthritis (21). The vast majority of information on cranial surgery is original, as well as several considerations on the diseases of the nervous system (e.g., epilepsy or mania), that were totally absent in the “Rogerina” (21,24). A chilling example is the following: «To cure mania, you should drill the skull at vertex, so that spirits can exhale, while holding the patient enchained» (Fig. 3) (21).

Figure 3.

Surgery to cure mania, according to Roland of Parma

All the work is based on direct observations and the only Authors cited are Hippocrates and a not better identified “Alexander” (maybe Alexander Aphrodisius or Alexander Abonuteichos or Alexander Filaletes or Alexander of Tralles or the unidentified Author of the Liber Alexandri de agnoscendis febribus et pulsibus et urinis) (21).

Both “Rogerina” and “Rolandina” have been firstly printed by Boneto Locatelli, Master printer in Venice, in the year 1498 (shortly after Gutenberg’s invention, in the years 1440-1455 in Germany, of the printing press), in the context of a “Collectio Chirurgica” (Surgical Collection) published by Ottaviano Scoto. Following this first publication both the textbooks have been widespread throughout Europe for centuries, being translated in several different languages, including a curious translation in Venetian dialect published by the University of Padua (21,24).

In 1250 Roland moved to Bologna, becoming “lecturer” (i.e., professor) in the local University. Probably he died in Bologna, after a long career as a surgeon and teacher in that University between the years 1280 and 1286 (25,26).

Conclusion

Shortly after the rise and full international recognition of the University of Bologna, another important University encompassing medical studies rose up in France, i.e., Montpellier. This town is located close to Avignon, that at the time was the seat of the Popes (from 1305 to 1377). This circumstance made Montpellier’s University, founded in 1220, very capable of gain financial support aimed to sustain both the academic work and the local Hospital, thus making Montpellier the main medical school in Europe for about one century (27,28). The most famous surgeon and professor of Surgery in Montpellier during the “Pope’s period” was the aforementioned Guy de Chauliac (1300-1368). He, in his “Cyrurgia” (published in Avignon, in 1363), classified 5 Schools of Surgery, posing at the first place “Roger and Roland of Parma”, thus certifying their universal reputation and celebrity (29-31).

Notably, a few years ago, Roland was cited in the Chest Surgery Clinics of North America as one of the pioneers of thoracic surgery for the account, in his treatise, of the repair of a wound with part of the lung leaking. In this description we also have an indirect form of informed consent and even of defensive medicine. In fact, before intervening Roland explained the possible consequences and asked permission not only to the wounded but also to God and the Bishop, relatives and friends to avoid revenge and accusations of witchcraft or illegal acts (32).

Aknowledgements

The pictures are part of an original copy of “Carbonelli G. Editor. La chirurgia di Maestro Rolando da Parma detto dei Capezzuti. 1927, Serono Edizioni, Roma”, property of one of the Autors (R.V.), and have been photographed by another Author (G.C.).

Conflict of interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article

References

- 1.Sudhoff K. Salerno, a Medieval Health Resort and Medical School. In: Essays in the History of Medicine. 1926, Garrison Ed [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castiglioni A. The School of Salerno (Work of Roger) Bull Hist Med. 1938;6:883. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Longobardi U, Mitaritonno M, Cervellin G. Salernitan Medical School or Langobardic Medical School? Acta BioMedica. 2020 doi: 10.23750/abm.v92i2.9109. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jarnut J. Geschichte der Langobarden. 1982, Stuttgart-Berlin-Köln-Meinz [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corner GW. The Rise of Medicine at Salerno in the Twelfth Century. In: Lectures on the History of Medicine. 1937, Mayo Foundation, Rochester. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keil G. Roger Frugardi und die Tradition langobardischer Chirurgie. Sudhoffs Archiv 2002;LXXXVI:1-26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Randel DM. “Guido of Arezzo”, in The Harvard Biographical Dictionary of Music. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 1996:339–340. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenman LD. The Chirurgia of Roger Frugard, 2002, X libris Corporation, Bloomington, Indiana [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bifulco M, Cavallo P. Thyroidology in the medieval medical school of Salerno. Thyroid. 2007;17:39–40. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dupuytren G. Clinical Lectures on Surgery. The Lancet. 1834;22:222–225. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dupuytren G. Treatment of goiter by the seton. The Lancet. 1833;21:685. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belloni L. Historical notes on the inclined inverted or so-called Trendelemburg position. J Hist Med All Sci. 1949;IV:372–381. doi: 10.1093/jhmas/iv.4.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tabaneli M. Studi sulla chirurgia bizantina: Paolo d’Egina. 1965, Olschki, Firenze [Google Scholar]

- 14.Briau R. La chirurgie de Paul d’Egine. 2011, Nabu Press, Firenze [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salem Elsheikh M. Chirurgia di Abu El Qasim. 1992, Zeta, Firenze [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawn B. I quesiti salernitani: introduzione alla storia della letteratura problematica medica e scientifica nel Medio Evo e nel Rinascimento. 1969, Di Mauro Ed., Cava dei Tirreni, Salerno [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freiberg JA. The mythos of laudable pus along with an explanation for its origin. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2017;7:196–198. doi: 10.1080/20009666.2017.1343077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pezzana Affò A. Memorie degli scrittori e letterati parmigiani. 1789. Parma. I. pag. 122-128; 1827, VI, pag. 47-52. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandrini E. La matricola del collegio medico di Parma. Annali di storia delle università italiane. 2002;6:211–228. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Virdis R. L’almo collegio dei medici di Parma e i primi medici iscritti. In “Lo statuto ritrovato”, Atti della giornata di Studi sullo Statuto dei Dottori delle Arti e della Medicina dell’Almo Studio Parmense, AMMI. Parma. 2018:19–36. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carbonelli G. La chirurgia di Maestro Rolando da Parma detto dei Capezzuti. 1927, Serono Edizioni, Roma [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linge W. Analysis of the Rolandina and comparison with the Surgery of Roger. 1925, in Isis, IV, pag. 585-600 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garosi A. Brevi considerazioni sulla “Cyrurgia magistri Rolandi Parmensis” Bull. Senese di Storia Patria. 1934;V:455–461. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grassi G. La chirurgia cranica nella Rolandina. in Humana Studia. 1941;L:27–36. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fattorini Sarti M. De claris archigymnasii Bononiensis professoribus. 1888. Bononiae. I. 2:536 ss. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazzetti A. Repertorio di tutti i professori della famosa università di Bologna. 1847, Bologna University Press: p. 269 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bullough VL. The development of the Medical University at Montpellier to the end of the fourteenth Century. Bull History Med. 1956;30:508–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guest-Gornall R. The Montpellier school of medicine. Practitioner. 1970;205:234–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Watters DA. Guy de Chauliac: pre-eminent surgeon of the Middle Ages. ANZ J Surg. 2013;83:730–734. doi: 10.1111/ans.12349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thevenet A. Guy de Chauliac (1300-1370): the “father of surgery”. Ann Vasc Surg. 1993;7:208–212. doi: 10.1007/BF02001018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Chauliac G. The Major Surgery of Guy de Chauliac. An English Translation by Leonard D Rosenman. Bloomington: Xlibris. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fell SC. A brief history of pneumonectomy. Chest Surg Clin North Am. 2002;12:541–563. doi: 10.1016/s1052-3359(02)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]