Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19) is an acute respiratory illness, caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus2 (SARS-COV2) which quickly grew to a pandemic in late 2019 and led to substantial public health problems. Among the extrapulmonary manifestations reported, cardiovascular implications are remarkable as they can be potentially lethal. There have been rare reports of pericardial involvement, despite the pronounced cardiovascular complications including acute myocardial injury, myocarditis, arrhythmia, cardiogenic shock and venous thromboembolism. Herein, we reported a young man with cardiac tamponade as the presenting feature of COVID-19.

Case summary

An otherwise healthy 28-year-old man, was admitted with pleuritic chest pain and shortness of breath and was diagnosed with COVID-19 associated cardiac tamponade. Emergency pericardiocentesis yielded large amount of hemorrhagic pericardial effusion which resulted in symptom relief. He was successfully treated with pericardiocentesis followed by anti-viral and anti-inflammatory medications and remained asymptomatic in 1-month follow-up.

Conclusion

We highlight this case to mention that “hemorrhagic” cardiac tamponade can be a life-threatening complication of COVID-19, which can be treated if diagnosed early. Therefore, clinicians should be fully aware of this cardiac complication to consider in deteriorating COVID-19 patients.

Abbreviation list

COVID-19=Coronavirus Disease 2019 SARS-COV2=Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 LVEF=Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction RR=Reference Range LDH=Lactate Dehydrogenase CPK=Creatine Phosphokinase CK-MB=Creatine Kinase-Myoglobin Binding RT-PCR= Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction cTNI=Cardiac Troponin I NT-pro-BNP=N-Terminal pro-B-type Natriuretic Peptide

What is important

Hemorrhagic cardiac tamponade should be considered as complication or presenting feature of COVID-19 infection. In this critical situation, intensive treatment must be initiated as soon as possible to reduce the mortality rate and avoid later complications. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: COVID-19, cardiac tamponade, pericardial effusion, case report

Introduction

SARS-COV2 infection, causes a mild illness in most cases, however in some patients it progresses to a severe respiratory disease characterized by hyperinflammatory syndrome, multi-organ failure and death. (1,2)

As the disease spread globally, various cardiovascular complications have been recognized. Studies suggest that these complications may be caused by the “activation of coagulation pathways, proinflammatory effects and endothelial cell dysfunction” by the virus.(3)we presented a case of covid-19 associated cardiac tamponade to emphasize this rare but life threatening complication of the disease.

Case presentation

A 28-year old man, with no known previous medical history, was admitted to the emergency department with a 6-day history of pleuritic chest pain and gradual-onset shortness of breath. The patient also noted going through upper respiratory tract infection symptoms (fever, malaise and rhinorrhea) a couple of days before the onset of above-mentioned symptoms which had got better gradually without seeking medical advice. Moreover, he reported new onset anosmia from one week before admission. The patient’s history of smoking was remarkable in his record.

Upon admission, his blood pressure was measured at 95/60 mmHg and he had tachycardia with heart rate of 125 beats per minute.

He was afebrile (temperature: 36.8 degree centigrade) and in respiratory distress with oxygen saturation of 85% in room air.

On physical examination heart sounds were determined to be muffled, no gallop or heart murmurs were detected and only tachycardia was noticed. The Jugular Venous Pressure (JVP) was also prominent (10 cm H2o) and lung auscultation revealed normal vesicular breath sounds.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE), acute coronary syndrome (ACS), myo-pericarditis and pneumonia.

Investigations

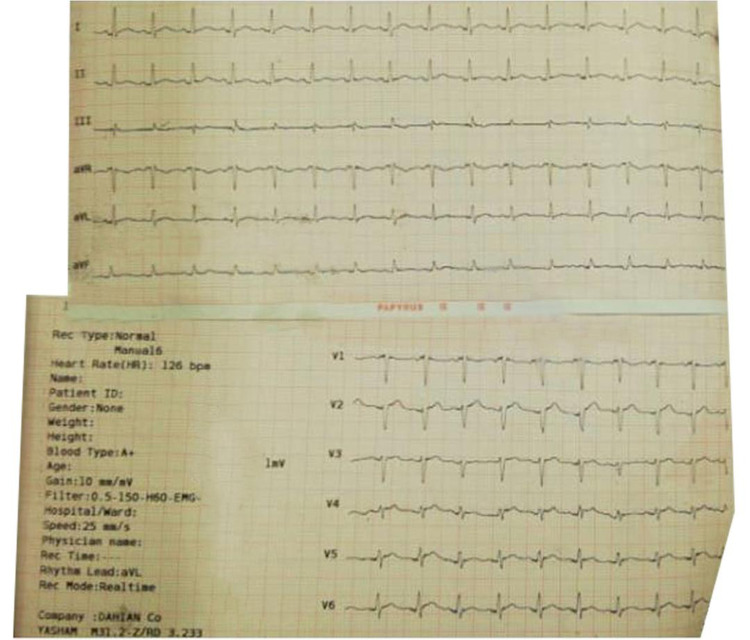

The electrocardiogram (ECG) taken at the beginning, indicated sinus tachycardia and electrical alternans with no significant ST-T changes. (figure 1)

Figure 1.

The patient’s electrocardiogram showing sinus tachycardia and some degree of electrical alternans.

Laboratory tests performed on admission showed polymorphonuclear dominant leukocytosis (white blood cell:12100, neutrophil:69.4%, lymphocyte:28.6%, monocyte:7%, eosinophil:3%), Anemia(Hemoglobin:11.5g/dl, MCV:78.43, MCH:25.05), elevated C-Reactive Protein (CRP=28.1 mg/dl; Reference Range(RR)< 5.9 mg/dl) and Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR=90 mm/hr) but cardiac biomarkers including cTnI, cpk and ck-mb levels were normal (cTnI:0.01 ng/ml, cpk:49, ck-mb:19.6). NT-pro-BNP (780 Pg/ml ; RR< 300) and D-dimer(4397 ng/ml ;RR= 0-500 ng/ml) levels were elevated.

Renal and liver function tests were within normal limits(urea:30.3 mg/dl, creatinine:1 mg/dl, Ast:33 u/l, Alt:64 U/L, Alp:311 u/l, total bilirubin:1.45 mg/dl)

Venous Blood Gas at the time of admission showed mixed respiratory acidosis and metabolic alkalosis (PH: 7.42 mmHg, PCo2: 51.9 mmHg, HCO3:32.2 meq /l).

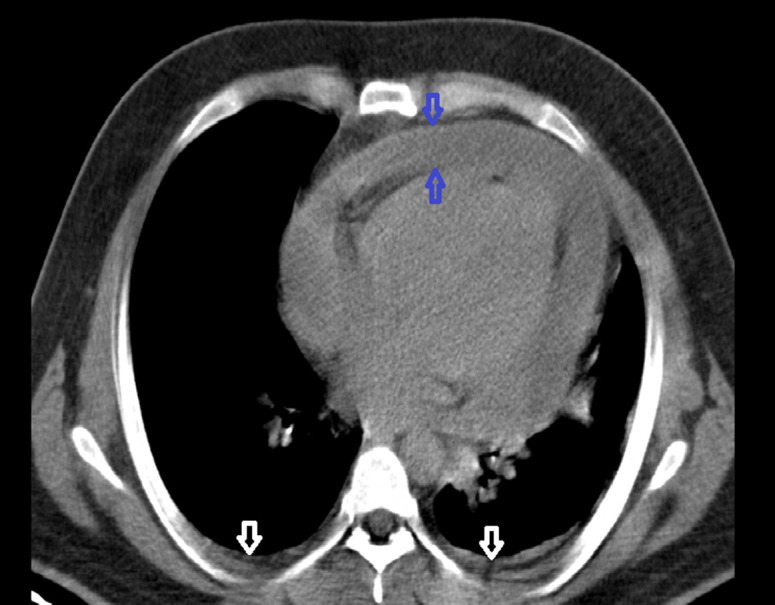

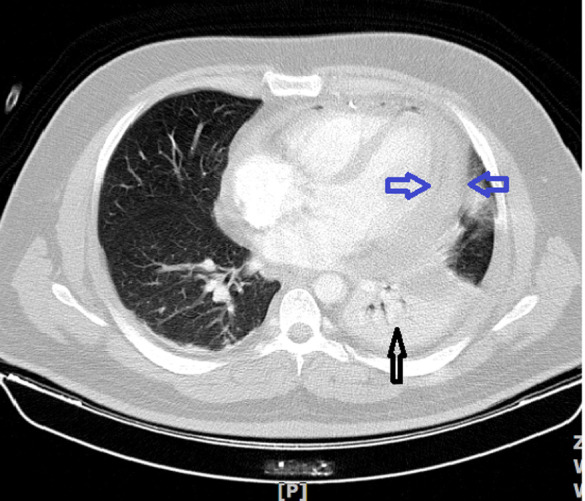

Considering the outbreak of COVID-19 and patient’s symptoms of dyspnea and pleuritic chest pain together with tachycardia, a Chest CT-scan with and without contrast was performed. The results indicated severe pericardial effusion (figure 2) and left lower lobe collapse consolidation accompanied with bilateral pleural effusion which was more prominent on the left side(figure 3). Furthermore, the scan showed no evidence of pulmonary thromboembolism.

Figure 2.

Chest CT scan evidences of pericardial effusion (blue arrows) together with bilateral pleural effusion (white arrows).

Figure 3.

Patient’s Chest CT scan showing Left Lower Lobe collapse consolidation (black arrow) and pericardial effusion (blue arrows).

An emergency echocardiogram showed a large pericardial effusion, Right atrial inversion and right ventricular diastolic collapse, with increased respiratory variation in mitral and tricuspid inflows and dilated Inferior Vena Cava consistent with cardiac tamponade. Cardiac systolic function was preserved (LVEF: 55%). (figure 4)

Figure 4.

2D echocardiography, parasternal long axis view, showing severe pericardial effusion (arrows).

Interventions

Fluoroscopic-guided catheter pericardiocentesis was done and 500 ml bloody fluid was drained instantaneously followed by another 200 ml gradual drainage within the next three days from the drainage catheter. Pericardial fluid analysis indicated Glucose:68 mg/dl, Red blood cell:320000, WBC:13000 (with 70% polymorphonuclear and 30% mononuclear), protein:4.9 g/dl, LDH:233 u/l, Adenosine deaminase (ADA):Negative(ADA level=25.6 ;RR < 33).

Pericardial fluid gram stain, culture and cytology were concluded negative. Pericardial fluid testing for SARS-COV-2 was not available at our center.

Patient’s respiratory distress and hypotension was resolved after pericardiocentesis was done and he was admitted into the Cardiac Care Unit.

Subsequent laboratory tests were also done to evaluate the causes of pericardial effusion. All collagen-vascular panel was negative. More, PPD and Bk smear of sputum were also negative.

Lipid profile, electrolytes, uric acid were within the normal range, and HIV Antibody, HCV Antibody and HBS Antigen results were proven negative.

Due to high clinical suspicion, a Polymerase Chain Reaction( PCR) test for novel coronavirus(SARS-COV-2) from a nasopharyngeal swab was performed which turned positive.(RT-PCR corona virus(RD-RP gene):positive, RT-PCR COVID-19(E-gene):positive)

Another positive PCR test result which was done with a 24hour-interval confirmed the diagnosis.

Based on positive COVID-19 PCR and pericardial involvement, the patient was treated with Lopinavir- Ritonavir 400/100 mg twice a day for 14 days. Also Ibuprofen 600 mg three times a day was prescribed for one week and was then tapered. Moreover, colchicine 0.5 mg twice daily was started and continued. His condition improved over the next few days and subsequently he was discharged from the hospital.

Follow-up

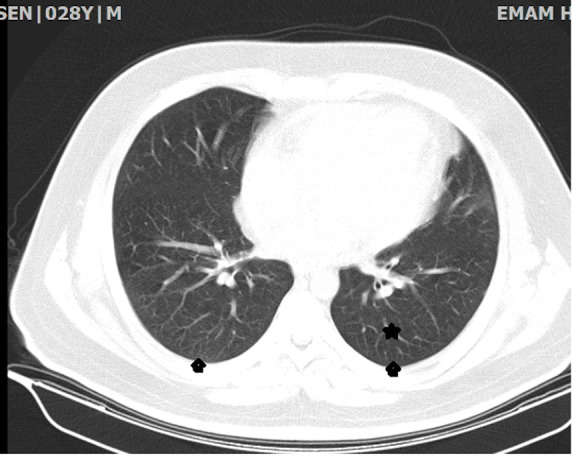

The patient had significant improvement with anti-viral as well as anti-inflammatory medications. In the 1-month follow-up, he remained asymptomatic and the control echocardiogram demonstrated only trivial residual pericardial effusion. Also pleural effusion and collapse consolidation on chest CT scan were resolved. (Figure 5)

Figure 5.

Follow-up chest CT scan showing resolution of pleural effusion (arrow heads) and collapse consolidation (star).

In the laboratory tests, anemia was corrected (Hemoglobin: 14), which may indicate that the initial hemoglobin drop could also be due to his hemorrhagic pericardial effusion.

Discussion

Coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19), caused by a novel Coronavirus (SARS-COV2), was first reported from Wuhan, China in late December 2019, and rapidly led to a global pandemic.(4)

To date, about 10.5 million confirmed cases have been documented from 213 countries, and 512842 of those cases have resulted in mortality (2 July 2020). (5)

Symptoms usually include fever, dry cough and shortness of breath and lungs are the most affected organs (6). However, there have been reports of extrapulmonary involvement such as cardiovascular implications from around the world. (7)

The cardiovascular implications of COVID-19 are important in several ways. In addition to the fact that patients with underlying cardiovascular diseases, are more likely to develop severe illness and higher mortality rate(8), COVID-19 causes a number of cardiovascular complications including acute myocardial injury, myocarditis, arrhythmia, venous thromboembolism and cardiogenic shock, however there have been rare reports of pericardial involvement.(9,10)

In a study, evaluation of chest CT scan findings in COVID-19 patients, revealed that pericardial effusion was seen in approximately 5% of these patients, which “may indicate the occurrence of severe inflammation”.(11)

Herein, we reported a young man with chest pain and progressive shortness of breath, who underwent pericardiocentesis due to evidence of massive pericardial effusion in Chest Ct scan and signs of cardiac tamponade on bedside echocardiography. As a consequence, significant improvement in his general condition was achieved following the drainage of large amount of bloody fluid.

The SARS-COV2 PCR was the only remarkable positive test result among the complete work up which has been done for evaluation of the possible causes of pericardial effusion. Complementary investigations for malignancy, Immune and inflammatory diseases (connective tissue disease, Dressler syndrome), hypothyroidism, TB and HIV were proven negative.

Our patient was a young man, presented with pleuropericarditis following the flu-like symptoms and anosmia. There were no other identified causes of pleuropericarditis other than COVID-19 infection which its PCR test turned positive for two times. Thus, his hemorrhagic pericardial effusion was attributed to the COVID-19 infection, as the most probable etiologic factor.

His pulmonary involvement was pleural effusion leading to collapse consolidation of left lower lobe, which was not typical for COVID-19, as there have been reports of cases of COVID-19 associated cardiac tamponade without the typical pulmonary involvement (12, 13). The remarkable point in this patient, was primary cardiac involvement by coronavirus without the typical radiologic findings of pulmonary involvement in chest CT scan.

Hemorrhagic pericardial effusion has been explained in pericarditis due to malignancy, tuberculous pericarditis, collagen-vascular diseases, uremia, trauma, irradiation, post myocardial infarction syndrome, streptococcal infection and idiopathic pericarditis. (14)

The association of bloody pericardial effusion with viral infections is less known but it has been reported in coxsackievirus. (15)

Patients with massive hemorrhagic pericardial effusion may be at risks of recurrence and constrictive pericarditis, if not treated intensively. (16) Therefore, in case of hemorrhagic pericardial effusion, intensive treatment must be started as soon as possible to prevent recurrence and constrictive pericarditis.

Among the rare reports of patients with cardiac tamponade secondary to COVID-19, the presence of bloody pericardial effusion in two patients were noted. (12, 17)

To our knowledge, our patient is the third case of “hemorrhagic” cardiac tamponade in the context of COVID-19 infection, but unlike previous cases he was a healthy young man with no previous comorbidity.

This suggests that COVID-19 can be a potential etiological factor of hemorrhagic cardiac tamponade and highlights the importance of further investigations on the mechanisms by which coronavirus causes hemorrhagic pericardial effusion.

We highlight this case to mention that hemorrhagic cardiac tamponade can be a life-threatening complication or presenting feature of COVID-19, which can be treated if diagnosed early. Therefore, clinicians should be fully aware of this cardiac complication to consider in deteriorating COVID-19 patients.

Consent

The author/s confirm that written consent for submission and publication of this case report including images and associated text has been obtained from the patient in line with COPE guidance.

Acknowledgement

Authors declare their thanks to the participating patient and staff of our cardiology ward.

Conflict of interest

none declared.

Funding Information

There was no funding or financial support for this report.

Disclosures

The authors have no relevant disclosures in regards to this article.

References

- 1.Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L, Song J. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive care medicine. 2020 Mar 3:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehra MR1, Desai SS1, Kuy S1, Henry TD1, Patel AN1. Cardiovascular Disease, Drug Therapy, and Mortality in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 May 1 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007621. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 3.Nguyen JL, Yang W, Ito K, Matte TD, Shaman J, Kinney PL. Seasonal influenza infections and cardiovascular disease mortality. JAMA cardiology. 2016 Jun 1;1(3):274–81. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.0433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. New Engl J Med. 2020 Jan 24 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World health organization. Coronavirus Disease(COVID-19)situation reports. 2020 https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200702-covid-19-sitrep-164.pdf?sfvrsn=ac074f58_2 . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sardu C, Gambardella J, Morelli MB, Wang X, Marfella R, Santulli G. Is COVID-19 an Endothelial Disease? Clinical and Basic Evidence. Preprints. 2020;10:20944. doi: 10.3390/jcm9051417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inciardi RM, Lupi L, Zaccone G, Italia L, Raffo M, Tomasoni D, et al. Cardiac involvement in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA cardiol. 2020 Mar 27 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng YY, Ma YT, Zhang JY, Xie X. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17(5):259–60. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Driggin E, Madhavan MV, Bikdeli B, Chuich T, Laracy J, Bondi-Zoccai G, et al. Cardiovascular considerations for patients, health care workers, and health systems during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2020 Mar 19 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vetta F, Vetta G, Marinaccio L. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Cardiovascular Disease: A Vicious Circle. J Cardiol Cardiovasc Res. 2020;1(2):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ye Z, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Huang Z, Song B. Chest CT manifestations of new coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a pictorial review. European Radiology. 2020 Mar 19:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06801-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dabbagh MF, Aurora L, D’Souza P, Weinmann AJ, Bhargava P, Basir MB. Cardiac Tamponade Secondary to COVID-19. JACC: Case Reports. 2020 Apr 23 doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inciardi RM, Lupi L, Zaccone G, Italia L, Raffo M, Tomasoni D, et al. Cardiac involvement in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA cardiology. 2020 Mar 27 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braunwald E. Pericardial disease. In: Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, editors. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012. pp. 1971–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamasaki A, Uchida T, Yamashita A, Akabane K, Sadahiro M. Cardiac tamponade caused by acute coxsackievirus infection related pericarditis complicated by aortic stenosis in a hemodialysis patient: a case report. Surgical case reports. 2018 Dec 1;4(1):141. doi: 10.1186/s40792-018-0550-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rivero A, Acena A, Orejas M, Hernandez-Estefania R. Recurrent haemorrhagic pericardial effusion due to idiopathic pericarditis: a case report. European Heart Journal-Case Reports. 2019 Mar;3(1):ytz018. doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytz018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh R, Fuentes S, Ellison H, Chavez M, Hadidi OF, Khoshnevis G, et al. Case of Hemorrhagic Cardiac Tamponade in a Patient with COVID-19 Infection. CASE: Cardiovascular Imaging Case Reports. 2020 Jun 4 doi: 10.1016/j.case.2020.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]