Abstract

Ultrasound can modulate activity in the central nervous system, including the induction of motor responses in rodents. Recent studies investigating ultrasound-induced motor movements have described mostly bilateral limb responses, but quantitative evaluations have failed to show lateralization or differences in response characteristics between separate limbs or how specific brain targets dictate distinct limb responses. This study uses high-resolution focused ultrasound (FUS) to elicit motor responses in anesthetized mice in vivo and four-limb electromyography (EMG) to evaluate the latency, duration, and power of paired motor responses (n = 1768). The results show that FUS generates target-specific differences in EMG characteristics and that brain targets separated by as little as 1 mm can modulate the responses in individual limbs differentially. Exploiting these differences may provide a tool for quantifying the susceptibility of underlying neural volumes to FUS, understanding the functioning of the targeted neuroanatomy, and aiding in mechanistic studies of this non-invasive neuromodulation technique.

Keywords: brain stimulation, focused ultrasound, locomotion, motor response, neuromodulation

Introduction

Brain neuromodulation consists of stimulating or depressing brain activity using exogenous stimuli. Methods with improved spatial, temporal, and functional selectivity can help to unravel the brain functioning and how complex neural circuits interact in time and space in the healthy and diseased brain. Despite the lack of a complete understanding of the mechanisms involved in the interaction of ultrasound waves with neuronal function (Kamimura et al. 2020a), the capability of focused ultrasound (FUS) in noninvasively eliciting motor responses has been demonstrated in multiple animal studies (Kim et al. 2014, King et al. 2014, Gulick et al. 2017, Mehic et al. 2014, Naor et al. 2016, Wang et al. 2020). Utilizing a lower-resolution FUS transducer with a large beam width on the murine brain (i.e., frequency: 500-kHz; focal width: 3 mm) has shown robust elicitation of limb movements at a wide array of brain targets both near the motor cortex and posterior brain regions.

Despite the robust motor response elicitation, an intriguing inconsistent or lack of lateralization of limb movements have been observed when sonicating the left and right portions of the motor cortex (King et al. 2014). These effects have been attributed to the potential simultaneous activation of subcortical structures arising from long acoustic foci due to the use of small aperture transducers in the kHz-range or the formation of extra-focal pressure peaks from standing waves due to the long pulse lengths typically implemented (Kamimura et al. 2015). The use of the megahertz-range can provide a millimetric spatial specificity of FUS (Li et al. 2016, Kamimura et al. 2016). Selective brain targets produced specific contra- or ipsilateral limb movements, and some of those targets elicited equal and opposite responses following sonication of the paired target in the opposite hemisphere using a high-resolution FUS transducer (frequency: 1.94-MHz; focal width: 1 mm) (Kamimura et al. 2016). Follow-up studies (Constans et al. 2018, Kamimura et al. 2020b) hypothesized that the temperature elevation resulting from the increase of the acoustic pressure necessary to transmit high-frequency pulses through the skull could enhance the FUS neuromodulatory effects. Interestingly, previous studies employing a high-resolution FUS transducer (frequency: 2-MHz; focal width: 1.5 mm) also reported inconsistent lateralization of limb responses (Mehic et al. 2014). Therefore, a detailed quantitative evaluation of motor responses elicited by high-frequency FUS pulses capable of eliciting motor responses while avoiding high-temperature elevation remains a gap in the literature.

In general, little is still known about the relationship between sonicated neural volumes and limb response characteristics and whether certain brain targets demonstrate lateralization of limb movements or preference for forelimb versus hindlimb movements. In this study, a high-resolution FUS sonication scheme using a shorter duration and a longer interval between successive pulses was used to favor non-thermal mechanisms. Four-limb EMG recordings were acquired in mice to determine whether FUS-elicited motor responses are target-specific and limb-dependent. Quantitative EMG evaluations of response latency, duration, and power were used to compare limb responses following FUS neuromodulation of brain regions often investigated in previous studies.

Materials and Methods

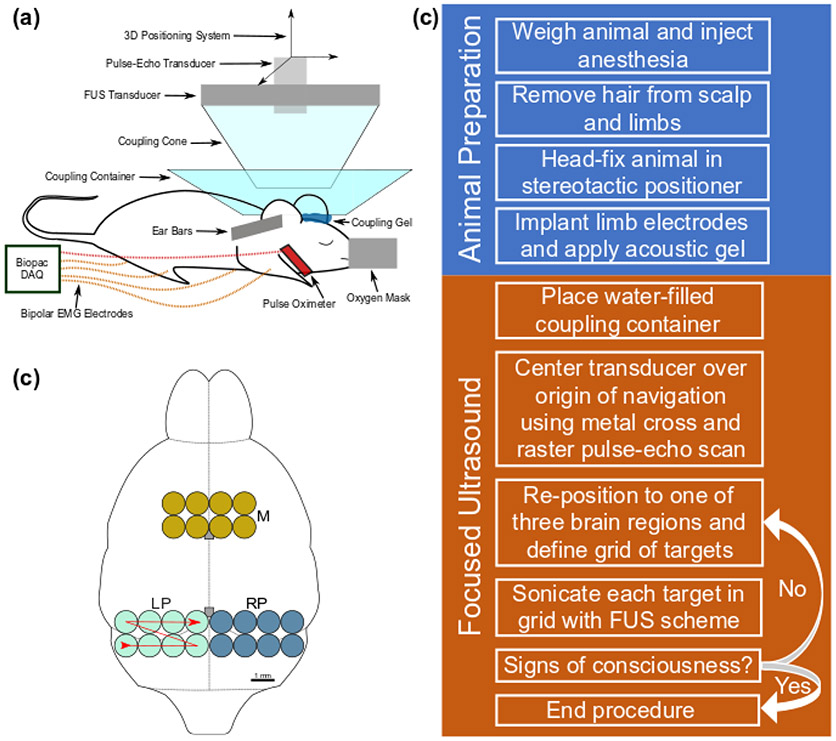

Animal Preparation

All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Columbia University. Wild-type mice (C57BL-6, 26.5 ± 3.2 g, n = 3) were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (65 mg/kg) and kept in the cage until toe pinches resulted in no pedal reflex. The hair was removed from the scalp and limbs using an electric razor and depilatory cream. The subject was mounted in a stereotaxic frame (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA, USA), and an electric heating pad maintained the animal’s body temperature for the duration of the experiment. An infrared pulse-oximeter sensor (MouseOx Plus, Starr Life Sciences Corp., Torrington, CT, USA) placed on the thigh indicated the depth of anesthesia. A pair of bipolar EMG electrodes was placed in each limb. The EMG and pulse-oximetry signals were recorded throughout the procedure (MP150, Biopac Systems, Inc. Santa Barbara, CA, USA).

Ultrasonic neuromodulation

A single-element 2-MHz FUS transducer (Imasonic SAS, Voray-sur-l’Ognon, France) mounted onto a 3-axis positioning system and controlled programmatically with MATLAB was driven by a function generator (33220A, Keysight Technologies Inc., Santa Rosa, CA, USA) with its signal amplified by a 50-dB power amplifier (ENI, Inc., Rochester, NY, USA). Water containers allowed for the acoustic coupling of the mouse head to the transducer (Figure 1a and Appendix A). Three sonication regions (Figure 1b), each consisting of eight targets in a 2 x 4 target grid, with targets spaced by 1 mm in both lateral dimensions, were chosen from spatially separate areas of the brain corresponding to areas investigated in the literature. A description of the targeting procedure is provided in Appendix B. The motor region (M) included most of the motor cortex. The two posterior regions were situated entirely in the left or right hemispheres, denoted LP (left posterior) and RP (right posterior), respectively. Each target was sonicated 10 times for statistical purposes before repositioning the transducer at the next target. The transducer was returned to the origin of navigation after sonicating an entire set of regional targets. Based on previous work (Kamimura et al. 2016), the acoustic parameters used in this study were: peak pressure (P) of 1.76 MPa, pulse repetition frequency (PRF) of 1 kHz, pulse length (tpl) of 0.5 ms, spatial peak pulse average intensity (ISPPA) of 97 W/cm2; calculated using Eq. 1 and the acoustic impedance of brain tissue, Z = 1.6x106 kg·sec−1m−2 (Azhari 2010). A summary of the transducer configuration can be seen in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Experimental setup. (a) The focused ultrasound system and signal acquisition equipment are labelled on the diagram of a head-fixed mouse in a stereotactic positioner. (b) An outline of the mouse brain is shown with the three brain regions investigated (M: motor, LP: left posterior, RP: right posterior). The red line denotes the sequence of target sonication from 1 to 8. Two grey boxes along the midline denote the bregma and lambda landmarks from top to bottom, respectively. (c) A general outline of the experimental procedure.

Table 1.

Methods Parameters

| Category | Parameter | Value/Model |

|---|---|---|

| FUS | Transducer | Single-element (radius of curvature = 60 mm, aperture = 70 mm, inner hole diameter = 20 mm, f -number = 0.86) |

| Focal Size | 1 mm (lateral) 8.7 mm (axial) |

|

| Center Frequency | 2 MHz | |

| Pressure (Intensity, ISPPA) | 1.76 MPa (97 W/cm2) | |

| Pulse Duration | 0.5 ms | |

| PRF | 1 kHz | |

| EMG | Electrodes | Bipolar, 0.0018” PTFE-insulated stainless-steel wire |

| Recording Sites | Triceps brachii (forelimbs), biceps femoris (hindlimbs) | |

| Data Acquisition | 0.5-5 kHz analog bandpass filtering 10 kHz sampling frequency 2000 gain factor |

FUS: focused ultrasound, EMG: electromyography, PRF: pulse repetition frequency

| (Eq. 1) |

Different from our previous work (Kamimura et al. 2016), sonications were applied for 300 ms at 5-second intervals (versus 1 s duration at 1 s interval used before) in order to reduce potential cumulative effects associated with repetitive sonications like temperature elevation. These acoustic parameters were used throughout the study since the goal was to evaluate differing response characteristics and not determine the efficacy of the full ultrasound parameter space.

The experiment was performed using light anesthesia levels with an average heart rate preceding the first successful response of 638 ± 69 min−1. Once responses were visually elicited and associated responses had been acquired from a region, the transducer was repositioned in one of the two other regions. The process of sonicating all the targets within a region and then repositioning the transducer in a different region was repeated until the animal showed signs of consciousness.

Electromyography (EMG)

Bipolar EMG electrodes were made in-house according to the procedure outlined by Tufail et al. (2011) using 0.0018” polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) insulated stainless steel wire (California Fine Wire, Grover Beach, CA). The electrodes were implanted into the triceps brachii and biceps femoris in the forelimbs and hind limbs, respectively. Ground reference electrodes were implanted underneath the skin of the back. Signals were sent through EMG-specific amplifier modules (EMG100C in hind limbs and EMG2-R in forelimbs, Biopac Systems, Inc., Goleta, CA, USA) with bandpass filtering between 500 Hz and 5 kHz with a gain factor of 2000. The signal was then digitized at 10 kHz using the data acquisition board (MP150, Biopac Systems, Inc., Goleta, CA, USA). A summary of the EMG configuration can be found in Table 1. Response latency and duration were evaluated using the root-mean-square (RMS) signals. Response latency was the time between stimulus onset and when the signal surpassed the activation threshold in the 300 ms window (i.e., duration of sonication) following the onset. Response duration was the cumulative time that the signal was above the activation threshold between the onset of the contraction (i.e., latency) and the 2 seconds following the FUS stimulus. The signal power was calculated by integrating the squared singular spectrum analysis-reconstructed EMG signals over 2 seconds following the FUS stimulus onset. Details on the EMG signal processing can be found in Appendix C.

Beam Profile Simulation

K-Wave, an open-source MATLAB-based simulation package for modeling ultrasound fields (Treeby and Cox 2010), was used to estimate the transcranial beam profile and pressure field patterns, including the formation of standing waves due to skull reverberations. A mouse micro-CT with 0.08 mm isotropic resolution and a Hounsfield unit conversion k-Wave script was used to determine the properties of the simulated skull-brain medium (Kamimura et al. 2015). Free water simulations were performed to find the optimal in silico transducer geometry to match water tank measurements using a hydrophone. This geometry was implemented in simulations using the simulated skull-brain medium. Two-dimensional simulations were performed for every brain target in the experiment.

Thermocouple measurements

An ultra-fast fine wire T-type thermocouple probe (maximum diameter: 0.28 mm, accuracy: ±0.1°C, time constant: 0.005 s; model IT-23, Thermoworks, USA) was used to measure subranial temperature elevation associated with sonication. A small window craniotomy was performed towards the lateral edge of the skull in an anesthetized mouse. The thermocouple was inserted towards the midline just below the skull surface, where the peak temperature rise is expected. A datalogger (DI-245, DataQ Instruments, Inc., USA) connected via USB port to a computer acquired the data at 2-kHz sampling frequency. The transducer was positioned over the location of the thermocouple. The full sonication scheme was then performed while the acquiring temperature readings from the thermocouple. Modeling of the Bioheat equation (Pennes 1948) based on previously developed techniques was used to remove the viscous heating effect (Kamimura et al. 2020b).

Statistical Analysis

Only targets with at least 4 successful responses were included in this analysis to avoid outliers due to random or inconsistent responses. A total of 5 regions across 3 mice produced sufficient four-limb responses to perform statistical analysis. Only targets with at least 4 successful responses were included in this analysis to avoid outliers due to random or inconsistent responses. A fixed-effects two-way ANOVA was used to determine the contribution of the two main effects (target and limb) as well as determine interactions between the sonicated brain targets and the motor responses in individual limbs. Tukey corrections were applied for multiple comparison tests when evaluating the main effects. Pearson correlations were used to evaluate the relationship between limb responses and EMG characteristics. Linear regressions were implemented to determine the effects of repetitive sonications. The stack of p-values associated with tests for non-zero slopes was subject to Holm-Sidak corrections for multiple comparisons. Mann-Whitney tests were used to evaluate response lateralization between hemispheres and to determine the effects of mediolateral target positioning. One-way ANOVA was used in the repeatability portion without corrections for multiple comparisons to more easily describe subtle trends over long periods.

Evaluation of auditory effects

To address a potential effect related to the startle responses from indirectly activating auditory pathways by FUS (Sato et al. 2018, Guo et al. 2018), an experiment was performed at two targets (Targets 6 and 7 in the RP and LP regions, respectively) in one subject to compare the responses from ultrasound stimuli, auditory stimuli, and a sham condition in which the function generator produced no output. Fifteen trials from each group were performed in a fully-randomized order at each location for a total of 30 from each group. The audible tone used was a 93.7 ± 2 dBC, 16 kHz tone, which is the peak hearing frequency of mice (Heffner and Heffner 2007), applied for the same duration as the 300 ms ultrasound stimulus. The responses from all conditions were bandpass filtered between 500 Hz and 3 kHz to remove interference arising from the auditory stimulus. The 300 ms window following the onset of the stimulus was evaluated. The tone was generated in MATLAB and broadcast through two computer speakers (Dell A225, Dell Technologies, Round Rock, TX, USA) placed approximately 7 cm on either side of the head-fixed mouse. The sound level of the tone was measured by a sound level meter application developed by the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health at the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Celestina et al. 2018).

Results

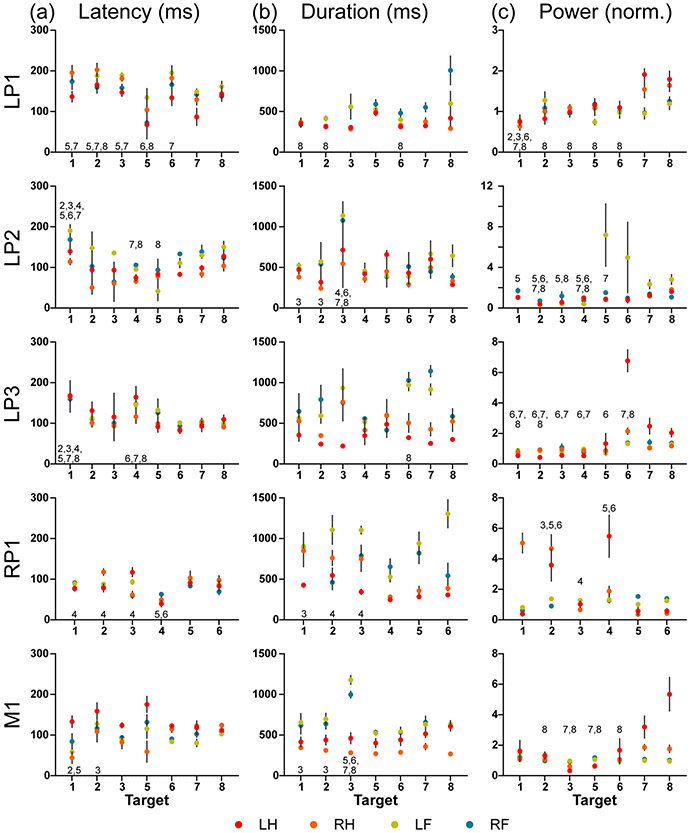

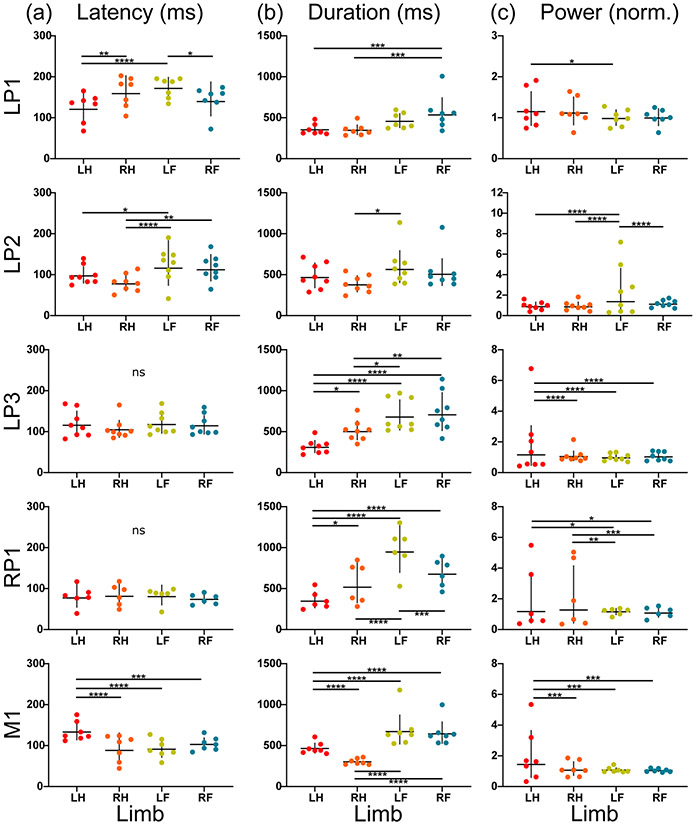

Three different regions were investigated: LP, RP, and M. The LP region was evaluated in 3 subjects (LP1, LP2, LP3), while the RP and M regions were each evaluated in one subject (RP1 and M1, respectively). The two main effects (target-based and limb-based effects) were used to demonstrate response differences without respect to the limb (target-based) and without respect to the target (limb-based). Each of the five total regions evaluated demonstrated significant target-based differences (p < 0.05) for all EMG characteristics evaluated: latency, duration, and power (Figure 2). Limb-based evaluations revealed significant differences (p < 0.05) among limbs in all regions for each EMG characteristic except for latency in regions LP3 and RP1 (Figure 3).

Fig. 2.

The four-limb EMG response (a) latency, (b) duration, and (c) power for the five regions (left posterior: LP1, LP2, LP3; right posterior: RP1; motor: M1) are shown grouped by targets (Targets 1-8). The geometric mean (+/− standard deviation) are denoted on each plot. A two-way ANOVA using target and limb as main effects and multiple comparison tests with Tukey correction were used to evaluate the significant main target effect. The significant pairings of targets (p < 0.05) are labeled by the target number showing significance. Significant pairings are not labeled reciprocally.

Fig. 3.

The four-limb EMG response (a) latency, (b) duration, and (c) power for each region (left posterior: LP1, LP2, LP3; right posterior: RP1; motor: M1) are shown grouped by limb (LH = left hindlimb, RH = right hindlimb, LF = left forelimb, RF = right forelimb). The geometric mean (+/− standard deviation) are denoted on each plot. A two-way ANOVA using target and limb as main effects and multiple comparison tests with Tukey correction were used to evaluate significance (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001).

The target-based effect on the EMG characteristics typically modulated limb responses in the same manner such that a target eliciting shorter average response latencies would result in shorter latencies among all limbs. Correlation analysis on the response latencies between each limb pair showed that limb activity was highly correlated, such that 25 of the 30 possible limb pairings across the 5 regions (6 pairwise comparisons per region) demonstrated significant positive correlations (p > 0.05) between limbs (Supplementary Figure 1).

However, the comparison using two-way ANOVA revealed significant interaction terms (p < 0.05) between the target- and limb-based effects in multiple regions for latency (RP1, M1), duration (LP1, LP3, RP1, M1), and power (LP1, LP2, LP3, RP1, M1). These interaction terms revealed that although response characteristics tended to be highly correlated, particular targets within regions with significant interaction terms affected limbs differently.

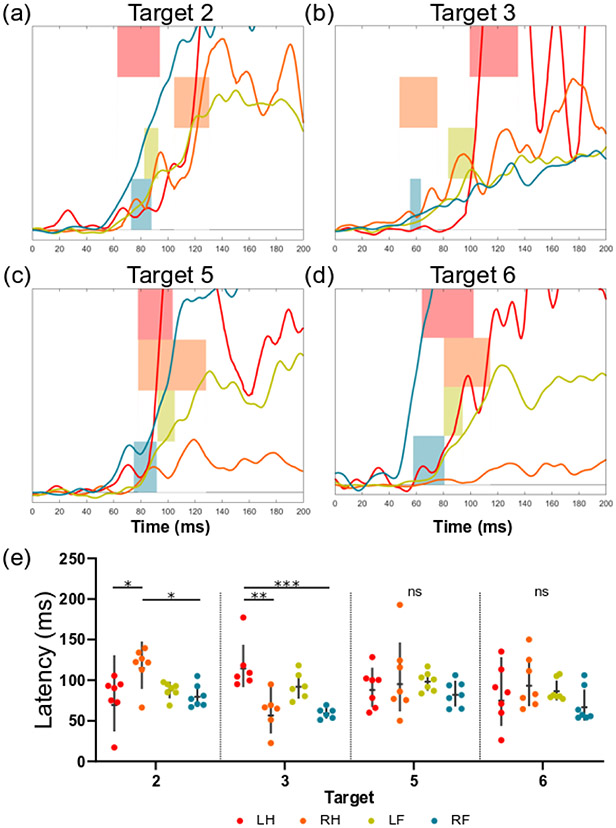

A more detailed evaluation of regions that exhibited significant target-limb interaction terms can be used to investigate how individual targets affect limbs differentially. Four targets with the highest response rate (n > 6) from region RP1 highlight the interaction effect on latency (Figure 4). Targets 2 and 3 both revealed significant differences in latency between the hindlimbs (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively). However, the left hindlimb had a shorter latency than the right at Target 2 (78.4 ± 27.2 ms and 117.6 ± 22.4 ms, respectively), while the right hindlimb had a shorter latency than the left at Target 3 (61.4 ± 21.7 ms and 117.2 ± 27.7 ms, respectively) while no differences between limb response latency were observed at Targets 5 and 6.

Fig. 4.

The effect of a significant interaction term for response latency is shown for four targets in the right posterior region (RP1 from Figure 2). (a-d) For each target, the RMS signals for the first 200ms post-stimulus onset are shown for each limb. The overlaid horizontal bars represent the 90% confidence interval of mean latencies for each limb. (e) The response latencies for each limb and target of interest are shown (geometric mean +/− geometric SD). Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used to evaluate the simple effects between limb groups for each target (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001).

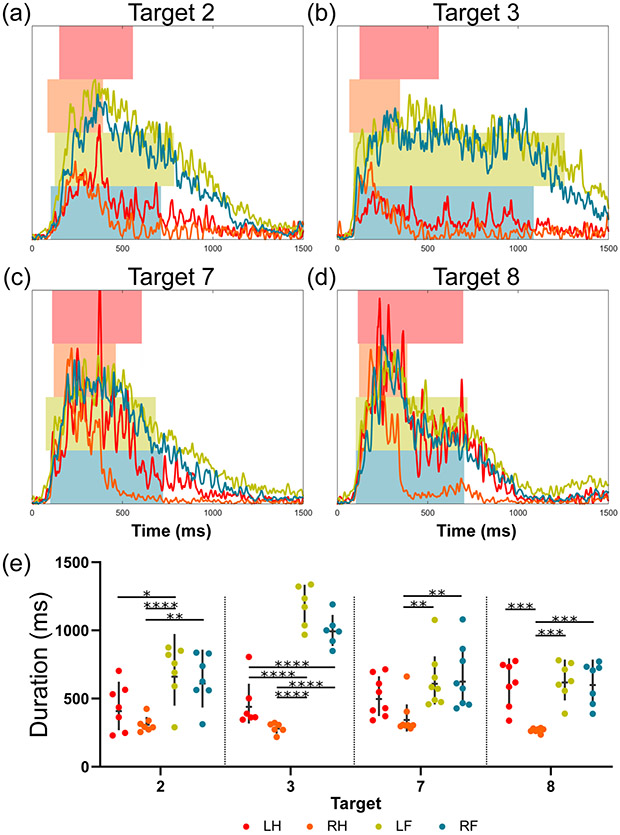

Similarly, four high response targets (n > 6) from region M1 show that the response durations in the four limbs depended on the target sonicated (Figure 5). At Target 3, the response duration of the left hindlimb (461.2 ± 162.3 ms) was significantly shorter than those of the left and right hindlimbs (1178.6 ± 137.4 ms and 998.3 ± 105.3 ms, respectively). However, at Target 8, there is no difference between response durations of the left hindlimb, left forelimb, and right forelimb (605.7 ± 153.0 ms, 632.9 ± 125.7 ms, and 617.6 ± 141.6 ms, respectively). In fact, the response durations of both forelimbs at Target 3 were longer than at any other sonicated target (Figure 2b).

Fig. 5.

The effect of a significant interaction term for response duration is shown for four targets in the motor region (M1 from Figure 2). (a-d) For each target, the first 1500 ms of the mean RMS signals are shown for each limb. Signal traces have been normalized by the regional maxima of each respective limb. The left and right bar edges of the overlaid bars represent the mean onset and offset of the motor activity, respectively. (e) The response durations for each limb and target of interest are shown (geometric mean +/− geometric SD). Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used to evaluate the simple effects between limb groups for each target (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001).

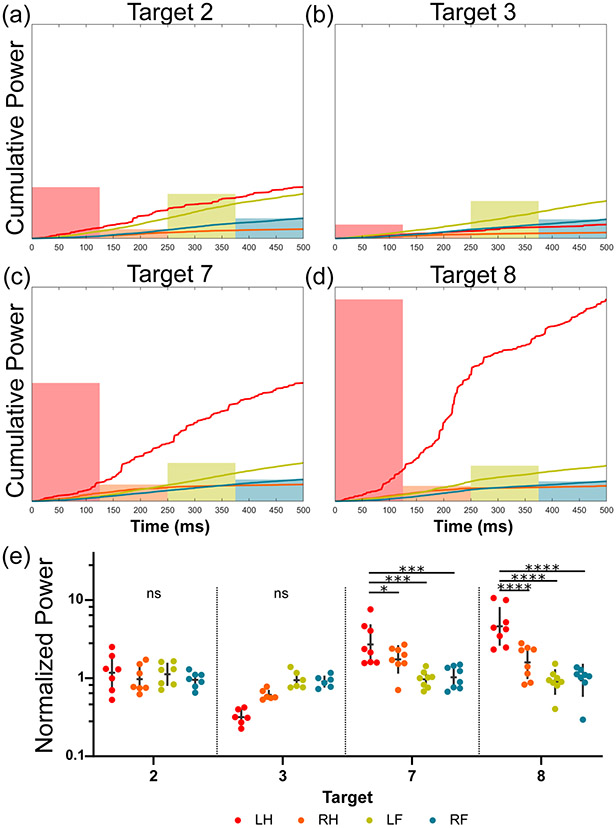

The target-limb interaction in response power was evaluated in region M1 (Figure 6) for four high response targets (n > 6). In this example, the left hindlimb revealed significantly higher power than the other three limbs at Targets 7 and 8 (p < 0.05). Although there were no power differences between limbs at Targets 2 or 3, it may be seen qualitatively that the left hindlimb is either the same or trends towards having a lower power than the other limbs.

Fig. 6.

The effect of a significant interaction term for response power is depicted for four targets in the motor region (M1 from Figure 2). (a-d) For each target, the mean cumulative power signals for the first 500 ms post contraction onset are shown for each limb. The overlaid bars represent the mean power of the motor response ensemble over this period, respectively. (e) The response power for each limb and target of interest is shown (geometric mean +/− geometric SD). Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used to evaluate the simple effects between limb groups for each target (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001).

The combined overall success rate for acquisitions from all limbs and subjects (n = 1874) was 81.1%. The mean latency and duration for these successful motor responses (n = 1521) were 104.83 ± 54.3 ms and 433.5 ± 108.6 ms, respectively. No differences in success rate were identified between limbs or between regions. An evaluation of the relationship between response characteristics was performed on all successful four-limb responses (Supplementary Figure 2). The response latency was significantly negatively correlated with both duration and power (p < 0.0001 and p < 0.001, respectively). In other words, the duration and power increased as latency decreased. Interestingly, response duration and power were also negatively correlated, such that the signal power increased when response duration decreased (p < 0.05).

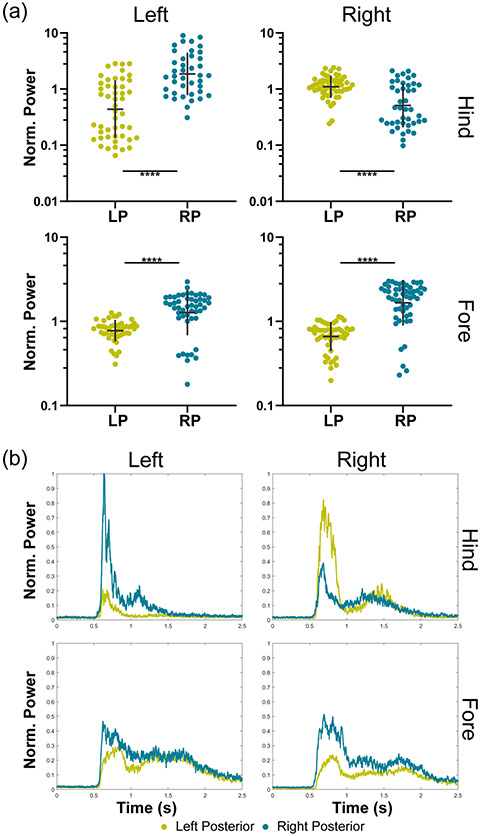

Another evaluation was performed to check whether observed motor movements demonstrated lateralization (Figure 7a). Responses from the LP3 and RP1 regions represent the left and right posterior regions of a single subject. The hindlimbs showed significant contra-lateralization of signal power between the left and right hemispheric targets (p < 0.0001). The forelimbs also presented a significant difference (p < 0.0001); however, the trend was the same for both groups such that the right posterior region generated a more robust response in both forelimbs. These effects can be seen qualitatively in the mean RMS envelopes for each limb (Figure 7b).

Fig. 7.

The evaluation of lateralization of responses is depicted by grouping responses from either the left or right posterior regions by limb and comparing response power. (a) The mean normalized responses for each limb are shown between the left posterior (LP) and right posterior (RP) groups. Mann-Whitney tests were used to make pairwise comparisons between the left and right posterior regions for each limb (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001). There were between 40 and 55 responses in each of the hindlimb groups and between 48 and 53 responses in each of the forelimb groups. Response power from the hindlimbs was significantly contra-lateralized. The response power of the left forelimb (LF) was significantly contra-lateralized, while the right forelimb (RF) was significantly ipsilateralized. (b) The RMS signals for each limb in each of the two regions are shown with the onset of ultrasound at 0.5 seconds.

Linear regressions were performed on the EMG characteristics at each target for all limbs and regions to evaluate whether repetitive sonications at 5-second intervals promoted or impeded responses in successive sonications. The slopes from the regressions were statistically tested to determine whether they were non-zero (Supplementary Figure 3). It was determined that there were no significant non-zero slopes for either response latency, duration, or power. Repetitive sonications at the interval used in this study did not affect the responses of successive sonications.

An in vivo thermocouple experiment was performed to evaluate the thermal effects of the transcranial FUS (Supplementary Figure 4). The parameters used in this study resulted in a peak temperature rise of 2.3 ± 0.1°C at the end of the last 300 ms pulse. The thermal energy did not accumulate over successive sonications, as observed in our previous study (Kamimura et al. 2016), where the peak temperature elevation at the end of 10 successive 1-s pulses was 6.8 ± 0.7°C. Any potential thermal effects were, therefore, trial-independent in the present study.

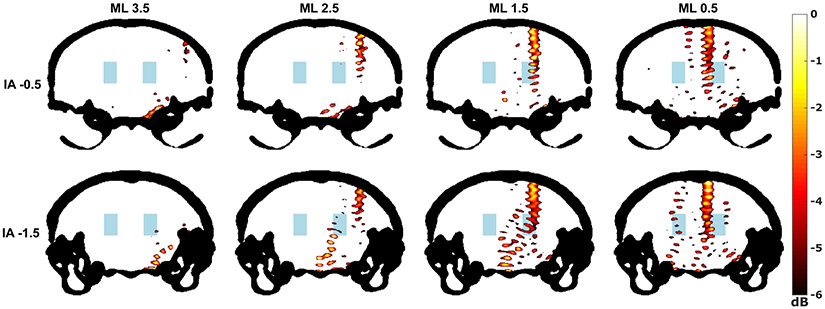

Simulations revealed that focusing through the skull was possible but that standing waves were present at locations in the skull cavity outside of the predicted acoustic focus, particularly near the center and base of the skull (Figure 8). Unsurprisingly, it was also observed that the de-focusing of the ultrasound beam increased at more lateral transducer positions where the incidence angle with the skull became less orthogonal. Lastly, simulations found that the side lobes of the ultrasound beam in certain transducer positions exceed −3dB of the peak negative pressure measured inside the focus.

Fig. 8.

Simulations were performed using k-Wave (Treeby and Cox 2010). The coronal slices corresponding to the front and back rows of the right posterior (RP) region were selected from a mouse micro-CT and used to determine the properties of the simulated propagation medium. Each of the eight targets of the RP region is shown and labeled by their mediolateral (ML) distance from the midline and from their distance from the interaural line (IA) in millimeters using mouse brain atlas coordinates (Paxinos and Franklin 2008). The peak pressure fields (dB scale) within the skull (black) are shown. Areas with pressure below −6dB are not colorized. The blue region represents the approximate location of the mesencephalic locomotor region (Roseberry et al. 2016).

An analysis of the effect of mediolateral positioning of the FUS transducer determined that there were no consistent significant differences between medial or lateral targets (Supplementary Figure 5). Only the duration characteristic for the forelimb comparison revealed slight significance (p = 0.0436) such that lateral targets exhibited longer response durations than medial targets.

A comparative post hoc evaluation of responses acquired at the same targets in the same subjects after periods longer than 15 minutes was performed to evaluate the repeatability of responses over time. The first region shows a high level of similarity between the two rounds (Supplementary Figure 6a). The second region did not show common significance between targets; however, trends may still be apparent qualitatively across successive rounds (Supplementary Figure 6b). A notable result is that the response latencies are significantly faster in the second rounds for both examples (p < 0.001).

The comparison of auditory stimuli, FUS, and sham demonstrated that FUS was significantly more effective at eliciting motor responses (p < 0.05). Of the 30 combined randomized trials, the auditory stimulus failed to elicit any motor responses, while FUS generated motor responses in 77% of trials with a mean latency of 54.6 ± 22.7 ms (n = 23). The sham condition yielded responses in 7% of trials with a latency of 171.9 ± 181.1 ms (n = 2).

Discussion

In this study, FUS brain neuromodulation was shown to elicit a variety of motor responses. Brain structures explored in previous studies were investigated with detailed quantitative EMG analysis of four-limb motor movements in mice. We found that given the size of the acoustic focus relative to the mouse-head and the distortion it undergoes passing through the skull, motor responses are more likely the outcome of a multitude of simultaneously activated (or inactivated) circuits that interact in complex ways, which may explain the inconsistent bilateral responses in previous studies. The distinct EMG responses obtained from the limbs show that unilateral sonications can neuromodulate different brain circuits that generate bilateral motor movements with target-specific characteristics. Our results suggest that bilateral responses are primarily elicited by subcortical activation and that FUS modulation of specific cortical and subcortical circuits generates target-specific motor responses.

The results for EMG response latency, duration, and power demonstrate the spatial specificity of FUS neuromodulation in all four limbs. EMG response characteristics varied significantly between brain targets. Although responses from all four limbs were significantly correlated and almost exclusively bilateral, individual brain targets did not always produce the same target-dependent differences across all limbs. In fact, the interaction terms from the two-way ANOVA identified brain targets producing unique divergences from the highly correlated responses such that limbs appeared to be affected differentially. This observation suggests that different neural circuits may be innervated at different targets. In other words, FUS does not necessarily elicit a whole-brain, non-specific, or startle response that results in motor movements. The correlation analysis between EMG characteristics evaluation revealed significant and intuitive relationships between the response latency, duration, and power. Faster latencies can be associated with more excitable brain targets and are therefore likely to result in more robust and more extended duration motor responses. A long latency brain target is either not very excitable or involves a preference towards inhibitory activity in those neural volumes, which would negatively affect the duration and magnitude of responses. Divergences from these trends may provide additional evidence of the relative excitability and functioning of the underlying neuroanatomy.

The mechanism of FUS neuromodulation likely involves cell-type-selective activation that affects the ion channels of neurons either directly or indirectly via manipulations of the plasma membranes (Kamimura et al. 2020a). It has been proposed that a neuron’s susceptibility to FUS is determined by its unique ion channel expression (Plaskin et al. 2014). In this manner, neural volumes in the brain, each with a high diversity of neuron classifications, are likely to have markedly different activation thresholds that can be independently manipulated by adjusting ultrasound parameters like pressure, pulse repetition frequency, and duty cycle. However, investigations of the parameter dependence of FUS neuromodulation are still in their infancy and the variability of neuron-type susceptibility in the brain it is not yet known, which confounds investigations like the present study because activation of, for example, low-threshold locomotion-associated regions in the midbrain may be the driving force for the bilateral motor responses observed presently and in literature. Parametric studies employing functional neuroimaging techniques can be used to help elucidate such differences.

Motor movements were elicited following sonication of an anterior region encompassing the motor cortex and two posterior regions spatially segregated from the motor cortex. Cortical microstimulation in the motor-related monkey precentral gyrus has shown that while short duration electrical stimuli generated muscle twitches, stimuli with behaviorally relevant durations (100-500 ms) resulted in a wide array of repeatable complex movements (Graziano et al. 2002) like bringing the subject’s hand to its mouth and even opening its mouth. The long duration motor responses typically observed in this study may similarly represent such coordinated movements. Although cortical activity is canonically contralateral to its physiological function, the ubiquity of bilateral responses observed in the present study and others may result from subcortical activation, either exclusively or in addition to cortical activation. Literature suggests that bilateral motor movements following unilateral stimulation of the motor region in mice can result from cortical activation under certain conditions. For example, eliciting ipsilateral movements requires much higher intensity stimuli than required to produce contralateral movements (Brus-Ramer et al. 2009). The ultrasound pressure employed in this study (1.76 MPa) may be high enough to elicit ipsilateral movements in a similar manner, or via activation of subcortical interhemispheric connections considering that FUS can induce subcortical activation at pressures as low as 1.20 MPa (Kamimura et al. 2016).

Stimulation of posterior regions in electrical and optogenetic experiments have also yielded bilateral motor movements. Posterior regions such as the mesencephalic locomotor region (MLR), which includes the cuneiform (CnF) and pedunculopontine (PPN) have been associated with locomotor control, although other nearby areas of the midbrain have also been indicated (Roseberry et al. 2016, Garcia-Rill et al. 1987, Caggiano et al. 2018, Bachmann et al. 2014). Locomotor control allows for the organization of stepping order and speed that result in different gait patterns like walking or galloping (Bellardita and Kiehn 2015, Roseberry et al. 2016), which can be selectively induced by adjusting electrical stimulation parameters like frequency and intensity (Garcia-Rill et al. 1987). Optogenetic stimulation of the CnF and PPN has also been shown to produce a wide range of speed and gait patterns with a latency of 100 to 150 ms (Caggiano et al. 2018). These observations indicate the possibility of locomotion-associated regions being responsible for the diversity of motor movements observed with FUS neuromodulation in posterior regions. FUS may elicit specific gait patterns like those demonstrated with established techniques, which could explain the differences in latencies between limbs observed in this study as latency differences would amount to a planned stepping order. For example, the alternating stepping order observed between neighboring targets in Figure 6e could simply represent different gait patterns. Differences in duration and power may similarly be explained with different gait patterns since more robust and more extended responses would correspond to stronger movements like bound or gallop (Bellardita and Kiehn 2015). For example, Figure 7e shows the forelimbs presenting a longer duration than the hindlimbs at one posterior location while demonstrating little or no difference at another. Optogenetic investigations of the basal ganglia have demonstrated that motor-related striatal neurons project to the MLR and that activating those neurons results in the initiation of locomotion and a general increase in spiking activity throughout the MLR (Roseberry et al. 2016). FUS-induced subcortical activation of motor-related striatal neurons may, therefore, also initiate locomotion.

The FUS sequence used in this study was designed with long interstimulus periods to mitigate thermal accumulation between consecutive sonications. Results showed that repetitive sonications did not produce the same accumulation of thermal energy between trials that may explain the unilateral responses observed in a previous study (Kamimura et al. 2016, Kamimura et al. 2020b). Although high-temperature elevations are sufficient to induce neuron depolarization (Shapiro et al. 2012), the temperature rise measured in this study was modest and occurred predominantly near the skull interface, making it unlikely to affect subcortical regions, particularly over the 40 ms period of some short-latency targets. It was also unknown whether repetitive sonications at individual targets could still result in excitatory or inhibitory cumulative effects from other factors like the depletion of neurotransmitters. However, linear regression analysis revealed that repetitive sonications at the interval applied in this study did not affect the EMG characteristics of successive sonications and were, therefore, determined to be independent of one another.

Recent studies have hypothesized that ultrasound-elicited motor responses may result from startle reflexes via the indirect activation of auditory pathways (Sato et al. 2018, Guo et al. 2018). However, a follow-up study (Mohammadjavadi et al. 2019) demonstrated that eliminating auditory pathways did not affect the ultrasound-elicited motor responses and that latencies of responses generated by ultrasound significantly exceed those from startle reflexes (~10 ms). The argument made by the authors was that, although the pulse repetition frequency and ultrasound frequency in most studies fall outside the established hearing range of mice (2.3-85.5 kHz), the square pulse envelopes induce high-frequency vibrations in the skull that do fall within that range (Heffner and Heffner 2007). The 16-kHz tone was therefore chosen in order to maximize the animal’s perception to auditory stimuli. The crude auditory evaluation performed in this study showed that responses from loud auditory stimuli (93.7 ± 2 dBC) were no different from sham group responses. An important limitation in this evaluation is that the exact magnitude of a perceived audible tone generated by FUS is unknown. However, the large differences observed in EMG characteristics, including the specificity of limb response sequences found in this study, provide support for a non-auditory mechanism since an auditory mechanism would likely demonstrate a non-specific response. Furthermore, the changes in conduction time of an auditory stimulus through the skull bone at neighboring targets are several orders of magnitude shorter than the differences in latency observed between them.

One limitation in this study was that the skull attenuates, distorts, and reverberates propagating ultrasound resulting in de-focusing and standing wave formations. Simulations confirmed that extra focal pressure peaks are generated in regions of the midbrain and near the base of the skull for both lateral and medial targets and that the long acoustic focus penetrated both cortical and subcortical brain regions. It is therefore not definitive where activation that initiated locomotion originated. Comparisons between motor responses from lateral and medial targets did not show consistent differences in their activity. However, the orientation of pyramidal axons differs between medial and lateral targets, which has an unknown effect on the activation threshold. Future work will require greater focal control of the acoustic energy in order to restrict activation more locally, for example, using coded excitation (Kamimura et al. 2015) or short-pulses (Morse et al. 2019).

Another limitation was the anesthesia utilized. Injectable anesthetics have inherently decreasing efficacy over time, and it is unknown how anesthetic mechanisms interact with that of FUS, making it difficult to determine whether changes in responses over time are due to the waning of anesthesia or that responses are not repeatable at individual brain targets (Jerusalem et al. 2019). Response latency trends were nevertheless demonstrated to be consistent over long periods but showed an overall decrease between rounds, likely a consequence of waning anesthesia. It is, therefore, possible that waning anesthesia levels during the regional sonication period (~7 mins) affect the observed differences between sequentially sonicated regional targets. Although this effect was not evaluated exhaustively, the results in Figure 2a suggest that the large non-linear changes in response latencies between targets were not primarily a result of lower levels of sedation. Nevertheless, randomizing the sonication order of targets and employing controlled rate infusions of anesthesia or non-sedated studies are recommended for all future investigations.

In summary, quantitative EMG analysis of FUS-elicited motor movements in anesthetized mice showed that limb sequence and contraction robustness depend on the neural target subject to FUS. Such differences are potentially a manifestation of activating subcortical locomotor-control regions shown capable of generating specific gait patterns in mice. The ability to generate bilateral motor responses is likely driven primarily by subcortical activation and potentially selectively modulated by inputs from activated areas of the cortex. These results also provide further evidence for neuron-type specific susceptibility to FUS and provide a quantitative technique for investigating the effects of employing a wider subset of the ultrasound parameter space in future work.

Conclusion

Detailed quantitative EMG analysis of four-limb bilateral motor responses elicited by FUS in mice in vivo reveals that response characteristics do not solely depend on the brain target subject to the sonication. Brain targets both anteriorly located near the motor cortex and posteriorly located near areas of the midbrain associated with locomotor control, respond to FUS in limb-dependent manners such that four-limb responses may even represent different gait patterns like those observed with established electrical or optogenetic techniques. These differences arise from sonicating targets separated by as little as 1 mm. Alternative driving forces like thermal accumulation, transducer orientation, or activation of auditory pathways do not account for the types of responses observed here. Our results provide further evidence for the proposed neuron-type specificity of FUS neuromodulation and introduce a quantitative metric for evaluating the effects of a wider subset of the ultrasound parameter space by identifying changes in limb patterns at individual targets and help understand the susceptibility of underlying neural volumes to FUS. This can facilitate future mechanistic studies of ultrasound neuromodulation techniques and guide future investigations towards clinical applications.

Supplementary Material

Supp. Fig. 1. The Pearson correlation coefficient matrices for response latencies between limbs (LH = left hindlimb, RH = right hindlimb, LF = left forelimb, RF = right forelimb) are shown for each of the five regions (left posterior: LP1, LP2, LP3; right posterior: RP1; motor: M1). Significant correlation coefficients (p < 0.05) are white and non-significant correlations are red. 25 of the 30 possible coefficients among the five regions were determined to be significant. The motor region demonstrated the least correlation of the regions evaluated.

Supp. Fig. 2. The correlation of the three motor response characteristics was evaluated using acquisitions from all limbs, targets, and regions with successful simultaneous responses in all four-limbs (n = 1768). Scatter plots with linear regression lines in red are shown for (a) latency versus duration and (b) latency versus power. The slopes of both regression lines are significantly non-zero (p < 0.0001 and p < 0.001, respectively). The response latency was significantly negatively correlated with both response power (p < 0.0001) and duration (p < 0.0001) such that power and duration tended to increase for shorter latency responses. Response power and duration were significantly negatively correlated (p < 0.05) such that power decreased as duration increased.

Supp. Fig. 3. The results of the cumulative effect investigation associated with repetitive sonications are shown. Linear regressions were performed on the response sets with successful simultaneous four-limb activation for every target sonicated. The p-values from tests for non-zero slopes were calculated and plotted for (a) latency, (b) duration, and (c) power. The stack of all p-values was subject to Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons revealing no significant trends (i.e., non-zero slopes) for any target.

Supp. Fig. 4. Transcranial thermocouple measurements were recorded in mouse brain in vivo (n = 3) with the viscous heating component removed using an iterative curve fitting technique (Kamimura et al. 2020b). The temperature elevation measured directly under the skull is shown for the parameters used in this study (0.3/4.7s on/off) and in the prior study by Kamimura et al. (2016) (1/1s on/off). The peak temperature elevation was 2.3 ± 0.1°C and 6.8 ± 0.7°C for the two studies, respectively. Additionally, no thermal accumulation occurred between trials in this study.

Supp. Fig. 5. The results for the mediolateral dependence of response characteristics are shown. The groups are separated by medial and lateral groups and further separated by forelimbs and hindlimbs to account for differences that may be inherent to them. The response (a) latency, (b) duration, and (c) power are shown for each grouping. Mann-Whitney tests were used to determine differences with the Holm-Sidak corrections for multiple comparisons (* p < 0.05). There was no significant difference between the evaluated groups, except for a modest difference for the duration characteristic in the forelimbs (p = 0.0436) such that lateral targets exhibited longer durations.

Supp. Fig. 6. A coarse evaluation of response repeatability was performed using the latency characteristic. Latency was used to determine similarities between successive rounds for these two regions belonging to two different subjects. (a) The first subject had a high degree of significant similarities between rounds. (b) The second subject did not show any common significant pairs; however, it can be seen qualitatively that a common trend exists between successive rounds. One-way ANOVA and multiple comparison tests without corrections were performed on the targets with at least 3 successful responses in each round. Only target pairs showing significance in both rounds are denoted with the lowest significance level from either round (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Supp. Fig. 7. Simulations were performed using k-Wave (Treeby and Cox 2010). The coronal slices corresponding to the front and back rows of the (a) motor and (b) right posterior regions, respectively, were selected from a mouse micro-CT and used to determine the properties of the simulated propagation medium. Each of the eight targets of the two regions is shown and labeled by their mediolateral (ML) distance from the midline and their distance from the interaural line (IA) in millimeters using mouse brain atlas coordinates (Paxinos and Franklin 2008). The peak pressure fields (dB scale) within the skull (black) are shown. Areas with pressure below −6dB are not colorized. The blue region represents the approximate location of the striatum in (a) and the mesencephalic locomotor region in (b), determined by Roseberry et al. (2016). The ultrasound could be successfully focused transcranially. However, extra-focal pressure peaks from standing waves are highly prevalent at all targets, particularly in areas of the midbrain and base of the skull.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through a National Cancer Institute grant R01EB027576.

Appendices

A. Transducer details

The transducer output was calibrated using a hydrophone (HNP-0200, Onda Corp., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) in a water tank both in free water and through an ex vivo mouse skull to determine skull attenuation and pressure levels. The transducer casing had an attached coupling cone filled with degassed water (Figure 1a). A custom degassed water-filled container was prepared with a window at its bottom and covered with an acoustically transparent membrane (Tegaderm, 3M Company, St. Paul, MN, USA). Degassed acoustically transparent gel (Aquasonic Ultrasound Transmission Gel, Bio-Medical Instruments, Inc., Clinton, MI, USA) was placed between the mouse head and the container.

B. Targeting procedure

A metal cross was first placed into the coupling container directly over the lambda skull suture, which is visible through the depilated scalp. The transducer was centered over the cross by performing a pulse-echo C-scan using a confocal single-element transducer (center frequency: 10 MHz, focal depth: 60 mm, diameter: 22.4 mm; model U8517133, Olympus NDT, Waltham, MA, USA). The metal cross was then removed from the coupling container. The transducer focus was repositioned 2 mm anterior of the lambda suture, which was used as the origin of navigation during targeting.

C. EMG Signal Processing

Singular spectrum analysis with a technique for automated window length selection was used for noise reduction in EMG signals (Vautard and Ghil 1989, Wang et al. 2015). The determined optimal window length was used for processing all EMG signals. Principal components were chosen that maximized signal during stimuli and minimized signal during off periods and used for all EMG processing. Nevertheless, EMG signals from an entire region were acquired in single files, subject to the same decomposition and reconstruction, and later separated by individual trials. This processing modality allowed for the use of constant activation thresholds for entire data sets instead of basing thresholds on the signal activity during pre-stimulus windows for individual trials as performed in other studies (King et al. 2014).

A moving root-mean-square (RMS) function with a 20 ms window length was used to generate signal envelopes for activation detection. The signal noise floor was fitted with a gamma distribution, and critical value (α = 0.001) was used to determine the activation threshold for each limb. Activation thresholds for each limb were used for all trials in a region. Trials were excluded if activity in the 60 ms window prior to stimulus surpassed the threshold. This conservative approach removed trials with even small amounts of activity in the pre-stimulus window (tprestim = 60 ms). Furthermore, only trials with simultaneous nonexcluded responses in all four limbs were used in statistical comparisons between limbs in order to remove intertrial variability.

References

- Azhari H Basics of biomedical ultrasound for engineers. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann LC, Matis A, Lindau NT, Felder P, Gullo M, Schwab ME. Deep Brain Stimulation of the Midbrain Locomotor Region Improves Paretic Hindlimb Function After Spinal Cord Injury in Rats. Sci Transl Med 2013;5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellardita C, Kiehn O. Phenotypic Characterization of Speed-Associated Gait Changes in Mice Reveals Modular Organization of Locomotor Networks. Curr Biol 2015;25:1426–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brus-Ramer M, Carmel JB, Martin JH. Motor Cortex Bilateral Motor Representation Depends on Subcortical and Interhemispheric Interactions. J Neurosci 2009;29:6196–6206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiano V, Leiras R, Goñi-Erro H, Masini D, Bellardita C, Bouvier J, Caldeira V, Fisone G, Kiehn O. Midbrain circuits that set locomotor speed and gait selection. Nature 2018;553:455–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celestina M, Hrovat J, Kardous CA. Smartphone-based sound level measurement apps: Evaluation of compliance with international sound level meter standards. Appl 2018;139:119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Constans C, Mateo P, Tanter M, Aubry J-F. Potential impact of thermal effects during ultrasonic neurostimulation: retrospective numerical estimation of temperature elevation in seven rodent setups. Phys Med Biol 2018;63:025003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Rill E, Houser C, Skinner R, Smith W, Woodward D. Locomotion-inducing sites in the vicinity of the pedunculopontine nucleus. Brain Res Bull 1987;18:731–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano MSA, Taylor CSR, Moore T. Complex movements evoked by microstimulation of precentral cortex. Neuron 2002;34:841–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulick DW, Li T, Kleim JA, Towe BC. Comparison of Electrical and Ultrasound Neurostimulation in Rat Motor Cortex. Ultrasound Med Biol 2017;43, 2824–2833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Hamilton M, Offutt SJ, Gloeckner CD, Li T, Kim Y, Legon W, Alford JK, Lim HH. Ultrasound Produces Extensive Brain Activation via a Cochlear Pathway. Neuron 2018;98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner H, Heffner R. Hearing Ranges of laboratory animals. JAALAS 2007;46. 20–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerusalem A, Al-Rekabi Z, Chen H, Ercole A, Malboubi M, TamayoElizalde M, et al. Electrophysiological-mechanical coupling in the neuronal membrane its role in ultrasound neuromodulation general anaesthesia. Acta Biomater. 2019;97:116–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josset N, Roussel M, Lemieux M, Lafrance-Zoubga D, Rastqar A, Bretzner F. Distinct Contributions of Mesencephalic Locomotor Region Nuclei to Locomotor Control in the Freely Behaving Mouse. Curr Biol 2018;28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamimura HAS, Wang S, Wu S-Y, Karakatsani ME, Acosta C, Carneiro AAO, Konofagou EE. Chirp- and random-based coded ultrasonic excitation for localized blood-brain barrier opening. Phys Med Biol 2015;60:7695–7712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamimura HAS, Wang S, Chen H, Wang Q, Aurup C, Acosta C, Carneiro AAO, Konofagou EE. Focused ultrasound neuromodulation of cortical and subcortical brain structures using 1.9 MHz. Med Phys 2016;43:5730–5735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamimura HAS, Conti A, Toschi N and Konofagou EE. Ultrasound Neuromodulation: Mechanisms and the Potential of Multimodal Stimulation for Neuronal Function Assessment Front Phys 2020a;8:150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamimura HAS, Aurup C, Bendau EV, Saharkhiz N, Kim MG, Konofagou EE. Iterative Curve Fitting of the Bioheat Transfer Equation for Thermocouple-Based Temperature Estimation In Vitro and In Vivo. IEEE T Ultrason Ferr 2020b;67:70–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Lee SD, Chiu A, Yoo SS, Park S. Estimation of the spatial profile of neuromodulation and the temporal latency in motor responses induced by focused ultrasound brain stimulation. NeuroReport 2014;25(7):475–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King RL, Brown JR, Pauly KB. Localization of Ultrasound-Induced In Vivo Neurostimulation in the Mouse Model. Ultrasound Med Biol 2014;40:1512–1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G-F, Zhao H-X, Zhou H, Yan F, Wang J-Y, Xu C-X, Wang C-Z, Niu L-L, Meng L, Wu S, Zhang H-L, Qiu W-B, Zheng H-R. Improved Anatomical Specificity of Non-invasive Neuro-stimulation by High Frequency (5 MHz) Ultrasound. Sci Rep 2016;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehić E, Xu JM, Caler CJ, Coulson NK, Moritz CT, Mourad PD. Increased Anatomical Specificity of Neuromodulation via Modulated Focused Ultrasound. PLoS ONE 2014;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadjavadi M, Ye PP, Xia A, Brown J, Popelka G, Pauly KB. Elimination of peripheral auditory pathway activation does not affect motor responses from ultrasound neuromodulation. Brain Stimul 2019;12:901–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse SV, Pouliopoulos AN, Chan TG, Copping MJ, Lin J, Long NJ, Choi JJ. Rapid Short-pulse Ultrasound Delivers Drugs Uniformly across the Murine Blood-Brain Barrier with Negligible Disruption. Radiology 2019;291:459–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naor O, Krupa S, Shoham S. Ultrasonic neuromodulation. J. Neural Eng 2016;13:031003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. Paxinos and Franklins the mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates: Paxinos George, Franklin Keith B.J.. London: Academic Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pennes HH. Analysis of Tissue and Arterial Blood Temperatures in the Resting Human Forearm. J Appl Physiol 1948;1:93–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaksin M, Shoham S, Kimmel E. Intramembrane Cavitation as a Predictive Bio-Piezoelectric Mechanism for Ultrasonic Brain Stimulation. Phys Rev X 2014;4. [Google Scholar]

- Roseberry TK, Lee AM, Lalive AL, Wilbrecht L, Bonci A, Kreitzer AC. Cell-Type-Specific Control of Brainstem Locomotor Circuits by Basal Ganglia. Cell 2016;164:526–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Shapiro MG, Tsao DY. Ultrasonic Neuromodulation Causes Widespread Cortical Activation via an Indirect Auditory Mechanism. Neuron 2018;98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro MG, Homma K, Villarreal S, Richter C-P, Bezanilla F. Infrared light excites cells by changing their electrical capacitance. Nat Commun 2012;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treeby BE, Cox BT. k-Wave: MATLAB toolbox for the simulation and reconstruction of photoacoustic wave fields. J Biomed Opt 2010;15:021314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vautard R, Ghil M. Singular spectrum analysis in non-linear dynamics, with applications to paleoclimatic time series. Physica D 1989;35:395–424. [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Ma H-G, Liu G-Q, Zuo D-G. Selection of window length for singular spectrum analysis. J Franklin Inst 2015;352:1541–1560. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Yan J, Wang Z, Li X, Yuan Y. Neuromodulation Effects of Ultrasound Stimulation Under Different Parameters on Mouse Motor Cortex. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2020;67:291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supp. Fig. 1. The Pearson correlation coefficient matrices for response latencies between limbs (LH = left hindlimb, RH = right hindlimb, LF = left forelimb, RF = right forelimb) are shown for each of the five regions (left posterior: LP1, LP2, LP3; right posterior: RP1; motor: M1). Significant correlation coefficients (p < 0.05) are white and non-significant correlations are red. 25 of the 30 possible coefficients among the five regions were determined to be significant. The motor region demonstrated the least correlation of the regions evaluated.

Supp. Fig. 2. The correlation of the three motor response characteristics was evaluated using acquisitions from all limbs, targets, and regions with successful simultaneous responses in all four-limbs (n = 1768). Scatter plots with linear regression lines in red are shown for (a) latency versus duration and (b) latency versus power. The slopes of both regression lines are significantly non-zero (p < 0.0001 and p < 0.001, respectively). The response latency was significantly negatively correlated with both response power (p < 0.0001) and duration (p < 0.0001) such that power and duration tended to increase for shorter latency responses. Response power and duration were significantly negatively correlated (p < 0.05) such that power decreased as duration increased.

Supp. Fig. 3. The results of the cumulative effect investigation associated with repetitive sonications are shown. Linear regressions were performed on the response sets with successful simultaneous four-limb activation for every target sonicated. The p-values from tests for non-zero slopes were calculated and plotted for (a) latency, (b) duration, and (c) power. The stack of all p-values was subject to Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons revealing no significant trends (i.e., non-zero slopes) for any target.

Supp. Fig. 4. Transcranial thermocouple measurements were recorded in mouse brain in vivo (n = 3) with the viscous heating component removed using an iterative curve fitting technique (Kamimura et al. 2020b). The temperature elevation measured directly under the skull is shown for the parameters used in this study (0.3/4.7s on/off) and in the prior study by Kamimura et al. (2016) (1/1s on/off). The peak temperature elevation was 2.3 ± 0.1°C and 6.8 ± 0.7°C for the two studies, respectively. Additionally, no thermal accumulation occurred between trials in this study.

Supp. Fig. 5. The results for the mediolateral dependence of response characteristics are shown. The groups are separated by medial and lateral groups and further separated by forelimbs and hindlimbs to account for differences that may be inherent to them. The response (a) latency, (b) duration, and (c) power are shown for each grouping. Mann-Whitney tests were used to determine differences with the Holm-Sidak corrections for multiple comparisons (* p < 0.05). There was no significant difference between the evaluated groups, except for a modest difference for the duration characteristic in the forelimbs (p = 0.0436) such that lateral targets exhibited longer durations.

Supp. Fig. 6. A coarse evaluation of response repeatability was performed using the latency characteristic. Latency was used to determine similarities between successive rounds for these two regions belonging to two different subjects. (a) The first subject had a high degree of significant similarities between rounds. (b) The second subject did not show any common significant pairs; however, it can be seen qualitatively that a common trend exists between successive rounds. One-way ANOVA and multiple comparison tests without corrections were performed on the targets with at least 3 successful responses in each round. Only target pairs showing significance in both rounds are denoted with the lowest significance level from either round (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Supp. Fig. 7. Simulations were performed using k-Wave (Treeby and Cox 2010). The coronal slices corresponding to the front and back rows of the (a) motor and (b) right posterior regions, respectively, were selected from a mouse micro-CT and used to determine the properties of the simulated propagation medium. Each of the eight targets of the two regions is shown and labeled by their mediolateral (ML) distance from the midline and their distance from the interaural line (IA) in millimeters using mouse brain atlas coordinates (Paxinos and Franklin 2008). The peak pressure fields (dB scale) within the skull (black) are shown. Areas with pressure below −6dB are not colorized. The blue region represents the approximate location of the striatum in (a) and the mesencephalic locomotor region in (b), determined by Roseberry et al. (2016). The ultrasound could be successfully focused transcranially. However, extra-focal pressure peaks from standing waves are highly prevalent at all targets, particularly in areas of the midbrain and base of the skull.