Abstract

Objectives:

To examine the relationship between pericardial fat (PCF) and cardiac structure and function among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients in the sub-Saharan African country of Uganda. People living with HIV (PLHIV) have altered fat distribution and an elevated risk for heart failure (HF). Whether altered quantity and radiodensity of fat surrounding the heart relates to cardiac dysfunction in this population is unknown.

Methods:

One hundred HIV-positive Ugandans on antiretroviral therapy were compared with 100 age- and sex-matched HIV-negative Ugandans; all were >45 years old with >1 cardiovascular disease risk factor. Subjects underwent ECG-gated non-contrast cardiac computed tomography and transthoracic echocardiography with speckle tracking strain imaging. Multivariable linear and logistic regression models were used to explore the association of PCF with echocardiographic outcomes.

Results:

Median age was 55 and 62% were female. Compared with uninfected controls, PLHIV had lower body-mass index (27 vs. 30, p=0.02) and less diabetes (26% vs. 45%, p=0.005). Median LV ejection fraction (LVEF) was 67%. In models adjusted for traditional risk factors, HIV was associated with 10.3 g/m2 higher left ventricular mass index (LVMI) (95% CI 3.22–17.4; p=0.005), 0.87% worse LV global longitudinal strain (GLS) (95% CI −1.66 – −0.07; p=0.03), and higher odds of diastolic dysfunction (OR 1.96; 95% CI 0.95–4.06; p=0.07). In adjusted models, PCF volume was significantly associated with increased LVMI and worse LV GLS, while PCF radiodensity was associated with worse LV GLS (all p<0.05).

Conclusions:

In Uganda, HIV infection, PCF volume and density are associated with abnormal cardiac structure and function.

Keywords: Pericardial fat, HIV, LV GLS

INTRODUCTION

Over the last 30 years, antiretroviral therapy (ART) has dramatically improved survival for the nearly 37 million people living with HIV (PLHIV) globally[1, 2]. Now, the risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD) is twice as high among PLHIV, and the total global burden of HIV-associated CVD has tripled in the last 20 years [3]. One contributor to CVD in this population is the development of adiposopathy (or “sick fat”), from a complex interaction of direct viral effects, ART, and underlying inflammatory processes [4, 5]. PLHIV are at increased risk of ectopic fat deposition [6, 7], as well as diastolic dysfunction (DD) and heart failure (HF) [8, 9, 10, 11]. Among the general population, increased pericardial fat (PCF) volume has been associated with increased cardiovascular events, stroke, and HF [12]; while decreased PCF density has been associated with increased coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores, independent of PCF volume [13]. Among PLHIV, PCF density has not been well studied, but increased PCF volume has been associated with increased CAC scores, myocardial perfusion defects, death, and myocardial infarction [14, 15, 16, 17]. Recently, HF with preserved ejection (HFpEF) has been associated with inflammation and abnormal fat depots [18, 19], which makes PLHIV an ideal study population for the development of this syndrome.

Although two-thirds of the global population of PLHIV reside in sub-Saharan Africa, where the population attributable risk of HIV-related CVD is the highest [1, 3], prior studies investigating the role of ectopic fat and cardiac dysfunction have been conducted mostly in males from high-income countries. Thus, there remains an unmet need to further characterize risk factors and surrogate markers of cardiac dysfunction in this population. Our primary objective was to determine whether PCF volume is associated with abnormal cardiac structure and function among PLHIV and uninfected controls in the sub-Saharan African country of Uganda. We further explored associations of HIV infection and novel measures of PCF radiodensity with cardiac structure and function.

METHODS

Study Group

We identified a convenience sample of 100 Ugandan PLHIV from the Joint Clinical Research Center near Kampala, Uganda currently on ART for >6 months with a stable regimen for >12 weeks prior to enrollment, and HIV viral load <400 copies/mL. These PLHIV were compared with 100 HIV-negative Ugandans recruited from internal medicine clinics in Kampala, Uganda who were prospectively age (+/−3 years)- and sex-matched to the PLHIV subjects. All subjects (PLHIV and controls) were >45 years of age and had at least one CVD risk factor (hypertension, low high-density lipoproteins [HDL], diabetes mellitus, smoking, or family history of early coronary artery disease). Patients were excluded if they had a history of known coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, or ischemic stroke, active uncontrolled chronic inflammatory condition, use of chemotherapy or immunomodulating agents (except for low dose aspirin), or estimated GFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2. Subjects were enrolled from April, 2015 to May, 2017.

All study procedures conducted in Uganda were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, the Joint Clinical Research Centre (JCRC; Kampala, Uganda) and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology. All subjects signed written informed consent. The JCRC Community Advisory Board was consulted for the design, conduct, and dissemination of our research.

2-Dimensional Echocardiography

Echocardiograms were performed with a Philips CX50 and a standardized protocol by a trained physician-sonographer. All 2-dimensional echocardiographic measurements of chamber size, left ventricular (LV) mass index, LV systolic function, and LV diastolic function were made based on the American Society of Echocardiography guidelines [20, 21]. Left atrial (LA) volume, LV volume, and LV ejection fraction (LVEF) were assessed using the biplane method of disks. When the LV endocardial border could not be reliably traced, the LVEF was estimated to the nearest 5% using all available views. Images with poor 2D or speckle tracking quality, E-A wave fusion, or missing wave forms were excluded from the relevant outcome measure.

Strain Analysis

Speckle tracking strain measurements were performed offline by a cardiologist (CLH), who was blinded to HIV status and clinical variables, using Image Arena, TomTec, 2D Cardiac Performance Analysis version 1.1.3. The LV endocardial border was traced at end-systole in the apical 2-, 4-, and 3-chamber views. The LV global longitudinal strain (GLS) was an average of 18 segmental peak systolic strain values. The intraclass correlation coefficient for repeated measurements of 20 randomly selected cases was 0.988.

Coronary Artery Calcium and Pericardial Fat Measurements

Subjects underwent ECG-gated non-contrast cardiac CT scans (128-slice Siemens Somatom) based on manufacturer recommended CAC scoring protocol with prospective ECG-gating at 60% of the R-R interval and tube voltage of 130kV as described previously [22].

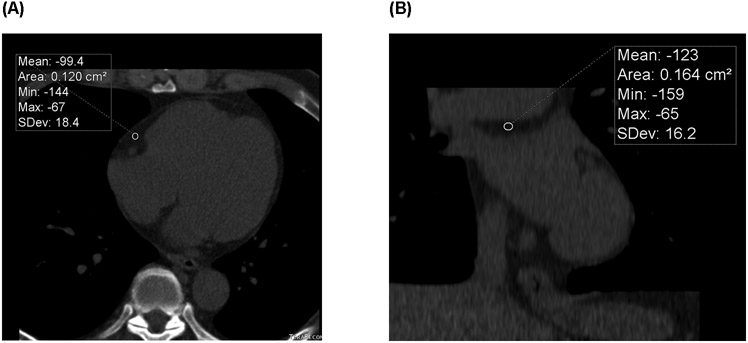

PCF volumes were quantified using a semi-automatic segmentation technique originally developed for the Framingham Heart Study [23]. The pericardium was manually traced on axial slices from the most cranial slice containing a coronary artery caudally through to the apex. Fat tissue was defined as pixels within a window of −195 to −45 Hounsfield Units (HU), and PCF was selected as all fat within the pericardial sac. Peri-aortic fat volume was identified as the fat surrounding the descending thoracic aorta (69 mm segment caudal to bifurcation of the pulmonary arteries). The PCF density was measured as the mean HU of a single 2 cm2 region of interest (ROI) in the right atrioventricular (AV) groove at the level of the proximal right coronary artery (RCA) (peri-RCA fat density) and the region above the LA (LA roof fat density) (Figure 1). Intraclass correlation coeffecients for repeated measurements made on n=20 subjects were excellent for PCF (ICC=0.981) and thoracic peri-aortic fat (0.974) and were in the good-to-excellent range for peri-RCA density (0.827) and LA roof fat density (0.795).

Figure 1. Example of Pericardial Fat with Radiodensity Measurements.

ECG-gated non-contrasted cardiac CT scan with a peri-RCA ROI measuring the mean HU in an axial view at the mid-RCA (large arrow) level (A), and a LA roof fat ROI measuring the mean HU in a coronal view (B). CT = computed tomography; HU = Hounsfield units; LA = left atrium; RCA = right coronary artery; ROI = region of interest

Statistical Analysis

Patient demographics, medical history, laboratory values, echocardiographic and CT variables were summarized as frequency (percentage) for categorical variables and median (interquartile range) for continuous variables, stratified by HIV status. Baseline characteristics were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables, and Pearson chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables as appropriate.

The primary analysis was to test the association of PCF volume with four echocardiographic measures of cardiac structure and function (LV mass index [LVMI], DD, LV GLS, and LVEF). The association of HIV and markers of PCF radiodensity (peri-RCA fat density, and LA roof fat density) with these four echocardiographic measures were tested in secondary analyses. For this sample of 200 total subjects and assuming a two-sided alpha of 0.0125 (adjusted for 4 comparisons) and 80% power, the minimal detectable effect size per one mL increase in PCF volume was 0.23 g/m2 for LV mass index, 0.10% for LV ejection fraction, and −0.03% for global longitudinal strain. The minimal detectable odds ratio for DD was 1.651 for one standard deviation increase in PCF above the mean.

The effect size of independent variables of interest (HIV, PCF volume, peri-RCA fat density, and LA roof fat density) on echocardiographic measures of cardiac structure and function (LVMI, DD, LV GLS, and LVEF) were calculated using unadjusted and multi-variable adjusted linear and logistic regression models. Co-variates in adjusted models were designated a priori for each model. Co-variates for the effect of HIV on echocardiographic outcomes included traditional CVD risk factors: age, sex, systolic blood pressure, diabetes, current smoker, and total cholesterol. Co-variates for the ectopic fat analyses additionally included HIV status and BMI (measure of total body adiposity).

Correlations between echocardiographic measures and HIV variables (current CD4+ cell count, nadir CD4+ cell count, duration of HIV, duration of ART, and current protease inhibitor use) were calculated using Pearson correlation coefficients for continuous variables or Point-Biserial correlation coefficients for binary variables.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). In general, a p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant and p <0.10 was considered borderline statistically significant. This threshold was adjusted for multiple comparisons in the primary analysis of the unadjusted association between PCF volume and the four echo parameters of interest, for which a p-value of 0.0125 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Baseline Subject Characteristics

The median age was 55 years and 62% were female. Compared to HIV uninfected controls, PLHIV had lower 10-year ASCVD risk scores (6.6% vs. 8.3%). PLHIV were less likely to have diabetes (26% vs. 45%) and had higher HDL levels (58 vs. 53 mg/dL). Although PLHIV had lower BMI (28.3 vs. 30 kg/m2), they had higher waist to hip ratio (WHR) (0.93 vs. 0.89), a marker of increased visceral adiposity. Overall, the rates of hypertension were high (85%) with a median systolic blood pressure of 152 mmHg, and rates of smoking were low (4%) but similar between groups. Subjects with HIV had a median CD4+ cell count of 531 cells/μL, median HIV duration of 11.7 years, and median duration of ART of 11 years. Approximately 19% were taking a protease inhibitor based regimen (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Cohort Characteristics Stratified by HIV Status

| HIV-Positive (N=100) |

HIV-Negative (N=100) |

Total Cohort (N=200) |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 54.5 (51 – 60) | 55 (50.5 – 60) | 55 (51 – 60) | 0.47 |

| Female | 62 (62%) | 62 (62%) | 124 (62%) | > 0.99 |

| Medical History | ||||

| Diabetes | 26 (26%) | 45 (45%) | 71 (35.5%) | 0.005 |

| Hypertension | 89 (89%) | 81 (81%) | 170 (85%) | 0.11 |

| Current Smoker | 4 (4%) | 4 (4%) | 8 (4%) | > 0.99 |

| Additional CVD Risk Factors | ||||

| BMI | 27.4 (23.3 - 32.0) | 30.4 (26.4 - 33.9) | 28.6 (25.1 - 33.3) | 0.02 |

| Waist:Hip Ratio | 0.91 (0.86 - 0.99) | 0.88 (0.84 - 0.94) | 0.90 (0.85 - 0.96) | <0.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 152 (140 - 167) | 152 (135 - 175) | 152 (138 - 170) | 0.40 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 217 (175 - 250) | 213 (181 - 245) | 215 (176 - 246) | 0.42 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 135 (107 - 166) | 139 (112 - 170) | 138 (110 - 169) | 0.91 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 58 (48 - 69) | 52 (44 - 60) | 55 (45 - 65) | 0.01 |

| ACC/AHA 10 yr ASCVD Risk (%) | 6.6 (3.3 - 10.9) | 8.3 (4.7 - 15.6) | 7.5 (4.1 - 12.4) | 0.05 |

| HIV Characteristics | ||||

| Current CD4+ Count (cells/μL) (N=71) | 531 (408 – 676) | NA | NA | NA |

| Nadir CD4+ count (cells/μL)(N=94) | 140.5 (68 – 215) | NA | NA | NA |

| HIV Duration (years)(N=94) | 11.7 (9.6 – 12.6) | NA | NA | NA |

| ART Duration (years)(N=97) | 11.1 (8.8 – 12.1) | NA | NA | NA |

| Current Protease Inhibitor Use | 19 (19.2%) | NA | NA | NA |

Values are n (%) or median (interquartile range).

Sample size is indicated at the top of the column unless otherwise noted.

ACC=American College of Cardiology; AHA=American Heart Association; ART=Antiretroviral Therapy; ASCVD=Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease; BMI=Body Mass Index; CAC=Coronary artery calcium; HDL=High-density lipoprotein; HIV=Human immunodeficiency virus; LDL=Low-density lipoprotein; SBP=Systolic blood pressure

Baseline Echocardiogram and CT Parameters

The median LVEF was 67% with no significant difference between groups, and only 9 subjects (4.5%) had an LVEF <50% (Table 2). Compared to controls, PLHIV had higher median LVMI [84.6 (IQR 68.1 - 102.8) vs. 74.1 (62.8 - 91.5) g/m2; p=0.007], but similar LV geometry (median regional wall thickness 0.49). More PLHIV had E/A ratio <0.8 (45% vs. 28%), with a numerically higher proportion of PLHIV with at least grade 1 DD (46% vs. 37%). However, there was no statistically significant difference between groups with regard to categorical DD, LA volume index [LAVI], or E/e’ ratios. PLHIV had significantly higher median PCF volumes [61 (IQR 44.7-79.7) vs. 48.9 (35.7-65.8) cm3; p<0.01; Table 3]. There was no difference in thoracic peri-aortic fat volume, peri-RCA fat density or LA roof fat density between groups. The majority of subjects had a CAC score of 0 (91%).

Table 2.

Echocardiographic Variables Stratified by HIV Status

| HIV-positive | HIV-negative | Total Cohort | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVEF (%) (N=194) | 67.9 (60.3 - 74.2) | 66.8 (60.1 - 74.2) | 66.9 (60.1 - 74.2) | 0.83 |

| LVMI (gm/m2)(N=179) | 84.6 (68.1 - 102.8) | 74.1 (62.8 - 91.5) | 79.7 (66.7 - 96.6) | 0.007 |

| Regional wall thickness (N=180) | 0.49 (0.42 - 0.55) | 0.49 (0.39 - 0.56) | 0.49 (0.41 – 0.56) | 0.54 |

| LV GLS (%)(N=196) | −16.0 (−18.0 - −14.5) | −17.0 (−19.2 - −14.6) | −16.4 (−18.8- −14.6) | 0.07 |

| LAVI (mL/m2)(N=194) | 20.7 (15.6 - 24.5) | 20.8 (16.4 - 25.3) | 20.8 (16.0 - 24.9) | 0.83 |

| Heart rate (beats/min)(N=200) | 73 (66 - 83) | 74 (67 - 81) | 74 (66 - 83) | 0.90 |

| E/A ratio (N=−176) | ||||

| <0.8 | 40 (45%) | 25 (28%) | 65 (37%) | 0.02 |

| 0.8-2.0 | 47 (53%) | 63 (72%) | 110 (62.5%) | |

| >2.0 | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Deceleration Time (ms) (N=176) | 235 (208 - 274) | 211 (187 - 250) | 223 (197 - 259) | 0.08 |

| E/e’ (N=172) | ||||

| <8 | 37 (44%) | 31 (36%) | 68 (40%) | 0.52 |

| 8 - 12 | 42 (49%) | 47 (54%) | 89 (52%) | |

| >12 | 6 (7%) | 9 (10%) | 15 (9%) | |

| Diastolic Dysfunction Grade (N=175) | ||||

| Normal | 48 (54.6%) | 55 (63.2%) | 103 (58.9%) | 0.38 |

| Grade 1 | 32 (36.4%) | 23 (26.4%) | 55 (31.4%) | |

| Grade 2 | 8 (9.1%) | 8 (9.2%) | 16 (9.1%) | |

| Grade 3 | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.2%) | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Grade 4 | --- | --- | --- | |

Values are n (%) or median (interquartile range).

Sample size is indicated by each variable (N).

HIV=Human immunodeficiency virus; LAVI=Left atrial volume index; LVEF=Left ventricular ejection fraction; LVMI=Left ventricular mass index

Table 3.

CT Variables Stratified by HIV Status

| HIV-positive | HIV-negative | Total Cohort | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pericardial Fat Variables | ||||

| Pericardial Fat Volume (cm3) (N=199) | 61 (44.7 - 79.7) | 48.9 (35.7 - 65.8) | 53.7 (38.7 - 74.2) | <0.001 |

| Peri-RCA Fat Density (HU) (N=199) | −94.7 (−114 - −71.3) | −95.8 (−115 - −70.7) | −95.5 (−114 - −71) | 0.84 |

| LA Roof Fat Density (HU) (N=199) | −61.3 (−78.7 - −52.8) | −66.7 (−82.9 - −52.7) | −63.5 (−79.6 - −52.8) | 0.19 |

| Coronary Artery Calcium Score (N=200) | ||||

| CAC = 0 | 88 (88%) | 94 (94%) | 182 (91%) | 0.36 |

| CAC = 1 – 100 | 7 (7%) | 4 (4%) | 11 (5.5%) | |

| CAC >100 | 5 (5%) | 2 (2%) | 7 (3.5%) | |

Values are n (%) or median (interquartile range).

Sample size is indicated by each variable (N).

CAC=Coronary artery calcium; CT=Computed tomography; HIV=Human immunodeficiency virus; LA=Left atrium; RCA=Right coronary artery

Effect of HIV Status on Cardiac Structure and Function

After adjusting for potential CVD risk factor confounders, PLHIV had 10.3 g/m2 higher LVMI (95% CI 3.22 – 17.4; p=0.005). Similarly, in adjusted models, PLHIV had modestly worse LV GLS (−0.87%; 95% CI −1.66 – −0.07; p=0.03) and borderline statistically significant increased risk of DD (OR 1.96; 95% CI 0.95 – 4.06; p=0.07) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Adjusted Effect* of HIV on Echocardiographic Variables of Cardiac Structure and Function

| LV Mass Index (g/m2) | Diastolic Dysfunction (OR) | LV GLS (%)† | LV Ejection Fraction (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect Size (95% CI) |

p value | Effect Size (95% CI) |

p value | Effect Size (95% CI) |

p value | Effect Size (95% CI) |

p value |

| 10.3 (3.2 - 17.4) | 0.005 | 2.0 (0.95 - 4.1) | 0.07 | −0.87 (−1.7 - −0.07) | 0.03 | 0.22 (−2.9 - 3.3) | 0.89 |

Adjustment variables: age, sex, systolic blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, current smoker, and total cholesterol

LV GLS is expressed as an absolute value change (i.e. negative change indicates worse strain and positive change indicates better strain).

In all models, HIV is the independent variable and the echocardiographic variables are the dependent variables. The effect size represents the difference in the continuous echocardiographic variable or odds of diastolic dysfunction among PLHIV vs. uninfected controls.

CI=confidence interval; GLS=global longitudinal strain; HIV=Human immunodeficiency virus; LV=left ventricular; OR=odds ratio

Effect of Pericardial Fat Volume and Radiodensity on Cardiac Structure and Function

In unadjusted models, PCF volume was associated with a significant increase in LVMI (0.22 g/m2 /cm3; 95% CI 0.08 – 0.37; p=0.002) and decrease in the LV GLS (−0.02% / cm3; 95% CI −0.03 - −0.004; p=0.02). Interestingly, the effects of PCF volume on LVMI were not substantially altered even when adjusting for BMI as a measure of total body adiposity or for WHR as a measure of visceral adiposity. Similarly, the association remained significant in fully adjusted models that further adjusted for traditional CVD risk factors (Table 5). The effect of PCF volume on LV GLS also remained significant in partially adjusted models after accounting for BMI or WHR, but did not meet statistical significance in fully adjusted models. There was no significant relationship observed between PCF volume and DD or LVEF (all p-values >0.1).

Table 5.

Effect of Pericardial Fat Volume on Echocardiographic Variables of Cardiac Structure and Function

| LV Mass Index (g/m2) | LV GLS (%)† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect Size (95% CI) | p value | Effect Size (95% CI) | p value | |

| Unadjusted Model | 0.22 (0.08 - 0.37) | 0.002 | −0.02 (−0.03 - −0.004) | 0.01 |

| Adjusted for HIV | 0.20 (0.05 - 0.34) | 0.009 | −0.02 (−0.03 - −0.001) | 0.04 |

| Adjusted for HIV and WHR | 0.18 (0.03 – 0.33) | 0.02 | −0.01 (−0.03 – 0.002) | 0.09 |

| Adjusted for HIV and BMI | 0.22 (0.07 - 0.37) | 0.004 | −0.02 (−0.03 - 0) | 0.05 |

| Adjusted for HIV, BMI, & CVD Risk Factors* | 0.17 (0.03 – 0.31) | 0.02 | −0.01 (−0.03 - 0.001) | 0.20 |

| Adjusted for HIV, WHR, & CVD Risk Factors* | 0.15 (0.02 – 0.29) | 0.03 | −0.01 (−0.03 – 0.004) | 0.14 |

CVD risk factors: age, sex, systolic blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, current smoker, and total cholesterol

LV GLS is expressed as an absolute value change (i.e. negative change indicates worse strain and positive change indicates better strain).

In all models, PCF is the dependent variable and the echocardiographic variables are the independent variables. The effect size is expressed as the corresponding change in the continuous echo variable or odds of diastolic dysfunction per 1 cm3 increase in PCF volume.

BMI=body mass index; CI=confidence interval; CVD=cardiovascular disease; GLS=global longitudinal strain; HIV=Human immunodeficiency virus; OR=odds ratio; PCF=pericardial fat; WHR=waist:hip ratio

In unadjusted models, peri-RCA fat density was associated with a significant reduction in GLS (−0.01% / HU; 95% CI −0.03 - 0.001; p=0.07), which remained significant after adjusting for HIV status, measures of adiposity, and other CVD risk factors (p=0.02). There was no significant association between peri-RCA fat density and LVMI, DD, or LVEF in unadjusted or adjusted models. There was no significant association between LA roof fat density and LVMI, DD, LV GLS, or LVEF in unadjusted or adjusted models (Table 6).

Table 6.

Effect of Pericardial Fat Density on Echocardiographic Variables of Cardiac Structure and Function

| LV Mass Index (g/m2) | LV GLS (%)† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect Size (95% CI) | p value | Effect Size (95% CI) | p value | |

| Peri-RCA Fat Density | ||||

| Unadjusted Model | 0.06 (−0.08 - 0.21) | 0.38 | −0.01 (−0.03 - 0.001) | 0.07 |

| Adjusted for HIV, BMI, & CVD Risk Factors* | 0.08 (−0.05 - 0.21) | 0.21 | −0.02 (−0.03 - −0.003) | 0.02 |

| Adjusted for HIV, WHR, & CVD Risk Factors* | 0.08 (−0.04 – 0.21) | 0.20 | −0.02 (−0.03 - −0.002) | 0.02 |

| LA Roof Fat Density | ||||

| Unadjusted Model | 0.19 (−0.04 - 0.43) | 0.10 | −0.01 (−0.03 - 0.01) | 0.39 |

| Adjusted for HIV, BMI, & CVD Risk Factors* | 0.11 (−0.10 - 0.32) | 0.30 | −0.006 (−0.03 - 0.02) | 0.62 |

| Adjusted for HIV, WHR, & CVD Risk Factors* | 0.11 (−0.09 – 0.32) | 0.28 | −0.005 (−0.03 – 0.02) | 0.67 |

CVD risk factors: age, sex, systolic blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, current smoker, and total cholesterol

LV GLS is expressed as an absolute value change (i.e. negative change indicates worse strain and positive change indicates better strain).

In all models, PCF radiodensity (peri-RCA or LA roof) is the dependent variable and the echocardiographic variables are the independent variables. The effect size is expressed as the corresponding change in the continuous echo variable or odds of diastolic dysfunction per one HU increase in PCF density.

HU= Hounsfield Units; BMI=body mass index; CI=confidence interval; CVD=cardiovascular disease; GLS=global longitudinal strain; HIV=Human immunodeficiency virus; LV=left ventricular; OR=odds ratio; PCF=pericardial fat; WHR=waist:hip ratio

In contrast to PCF, thoracic peri-aortic fat volumes were not associated with echocardiographic measures in any of the models (all p-values >0.05).

Correlation of HIV Variables and Cardiac Structure and Function

Current CD4+, nadir CD4+, duration of HIV, duration of ART, or use of protease inhibitors did not correlate with LVMI, GLS, or LVEF (all p >0.1; Supplemental Table 1).

DISCUSSION

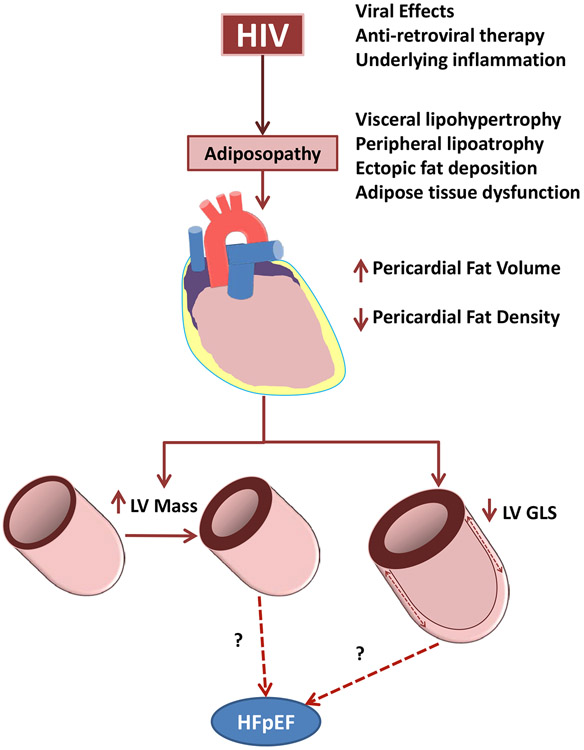

We and others have separately demonstrated in prior studies that PLHIV in high-income countries have alterations in ectopic fat deposition and increased risk of HF [6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]; however, these prior studies of PLHIV have not explored alterations in ectopic fat (i.e. “adiposopathy”) as a potential mechanism leading to clinical HF risk. Furthermore, none of these studies have been conducted in sub-Saharan Africa, where higher proportions of PLHIV are women and where population attributable risk of HIV-related CVD is highest [3]. Our current study begins to explore adiposopathy as one of many potential mechanisms of clinical HF risk in HIV by demonstrating that HIV-positive Ugandans have significantly more PCF volume, and that PCF volume and density are associated with abnormal cardiac structure and function, as evidenced by increased LV mass and decreased LV GLS (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Conceptual Interaction of HIV, Pericardial Fat, and Cardiac Structure and Function.

Chronic HIV infection contributes to adiposopathy through direct viral effects, ART, and underlying inflammatory process. This includes the development of increased pericardial fat volume with lower radiodensity on CT imaging. These changes in pericardial fat are associated with increased LV mass index and decreased LV GLS, independent of traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors. It remains to be seen whether these changes lead to the development of HFpEF. ART = antiretroviral therapy; CT = computed tomography; GLS = global longitudinal strain; HFpEF = heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; LV = left ventricular

HIV and Cardiac Structure and Function

Prior studies have identified HIV as a risk factor for subclinical alterations in cardiac structure and function [3, 24] and higher risk of clinical HF [8, 9, 10]. Studies of cardiac dysfunction in sub-Saharan Africa have included higher proportions of persons with more advanced immunosuppression. Our study confirms that well-treated Ugandan PLHIV with relatively normal CD4+ T-cell counts had on average 10.5 gm/m2 higher LVMI compared to HIV-negative subjects, and that this did not seem to be confounded by differences in traditional CVD risk factors. Furthermore, such alterations of myocardial structure may be leading to a statistically borderline doubling of DD risk and modestly worse LV GLS.

Prior studies from sub-Saharan Africa have described a higher prevalence of reduced LVEF. Our findings are consistent with more contemporary ART-treated PLHIV in high-income countries [24]. The worse LV GLS and increased LV mass among PLHIV may presage overt clinical myocardial dysfunction (i.e. HF); however, this hypothesis requires further investigation. High rates of poorly treated hypertension, a well-established risk factor for DD, were seen in both PLHIV and control cohorts (85%), which may have attenuated the effect of HIV specific factors. Furthermore, our PLHIV had relatively well controlled HIV (average CD4+ of 570 cells/μL), whereas more advanced immunosuppression has been associated with myocardial dysfunction [25].

Pericardial Fat Volume and Cardiac Structure

In this first study of PCF from sub-Saharan Africa, Ugandan PLHIV had significantly higher PCF volumes (61 cm3 vs. 49 cm3). Furthermore, PCF volume was associated with increased LVMI and worse LV GLS. Yet, because of small sample size, these data should be interpreted cautiously as a type-1 error may be possible.

PCF volume has been associated with HF and increased LVMI [12], and among PLHIV, PCF volume is associated with increased intra-myocardial fat [26]. PCF is hypothesized to contribute to CVD progression through inflammatory responses via systemic endocrine and direct local paracrine effects [5]. Even after controlling for measures of visceral adiposity (i.e. WHR), the effect of PCF volume on LVMI remained. Thus, our data suggest that increased PCF volume in PLHIV may lead to the development of abnormal myocardial structure and function, independent of other risk factors.

Pericardial Fat Density

Decreased PCF radiodensity is associated with increased adipocyte hypertrophy and lipid content [27] whereas increased PCF density may be due to inflammatory cell infiltration [28, 29]. Lower PCF density has been associated with increased CAC scores, independent of PCF volume, age, and BMI [13]. Conversely, higher peri-coronary radiodensity may reflect perivascular fat inflammation, which may directly affect coronary atherosclerosis and myocardial function. In our study we measured PCF density from two separate regions of interest (peri-RCA and the LA roof), and have shown for the first time that among HIV-positive subjects in sub-Saharan Africa, higher peri-RCA fat density was significantly associated with worse LV GLS, independent of HIV status, BMI, WHR, or other CVD risk factors. Interestingly there was no association between LVMI and PCF density, despite the strong associations we observed with PCF volume and LVMI. The association of PCF density with adverse clinical outcomes may be independent of PCF volume [13, 30], thus suggesting different mechanisms may account for these clinical effects.

Study Limitations

Although ours is the first of its kind to investigate the effects of PCF volume and density on cardiac structure and function among PLHIV in sub-Saharan Africa, the sample size may not have been adequate to detect some clinically important associations. Furthermore, while the associations between abnormal cardiac structure, DD, and systolic function (i.e. LVEF and LV GLS) are important, these outcomes do not represent the clinical syndrome of HF, which would require further investigation and longer term follow up. Our study purposefully targeted persons with ART-treated HIV infection, whereas prior data have suggested that untreated HIV is associated with worse cardiac outcomes. In addition, our population had higher rates of diabetes. Thus, our findings may not be applicable to areas of sub-Saharan Africa with limited access to ART or lower rates of diabetes. Finally, we sought to investigate the role of PCF specifically in this high-risk, endemic region of the world, and thus our findings may provide insight for PLHIV in other geographic areas, but should be applied with caution.

CONCLUSIONS

The paradigm for the development of myocardial dysfunction with a normal LVEF (i.e HFpEF) has shifted to focusing on underlying pro-inflammatory states [19], and HIV represents an ideal study model given the nature of the infection, treatment strategies, and association with co-morbid conditions such as adiposopathy. Our study shows that in the sub-Saharan country of Uganda, HIV infection is associated with increased PCF volume, and PCF volume and radiodensity are in turn associated with increased LV mass and worse LV GLS. While abnormal LV mass and LV GLS may be indicative of the early progression to HFpEF, further studies are needed to investigate the association of HIV and PCF with clinical HF syndromes in this endemic area.

Supplementary Material

What is already known about this subject?

People living with HIV (PLHIV) have altered fat distribution, including an increased risk for the development of pericardial fat (PCF), and an elevated risk for heart failure (HF). Whether altered quantity and radiodensity of fat surrounding the heart relates to cardiac dysfunction in this population is unknown. PLHIV whom reside in sub-Saharan Africa, have the highest attributable risk of HIV-related CVD.

What does this study add?

Among Ugandans with HIV, PCF volume is significantly increased, and is associated with increased LV mass and decreased LV GLS, independent of other risk factors. PCF density is also associated with decreased LV GLS. Thus, PCF volumes and radiodensity, may help identify PLHIV at higher risk for cardiac dysfunction.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

As the global population of PLHIV continues to grow, the risks of development of CVD, such as HFpEF, are becoming more prevalent and understanding the risk factors and mechanisms are vital. Our data provide insight into one possible mechanism for development of abnormal cardiac structure and function among PLHIV.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (K23 HL123341 to CTL).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive license (or non exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in HEART editions and any other BMJPGL products to exploit all subsidiary rights

REFERENCES

- 1.Fettig J, Swaminathan M, Murrill CS, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2014;28:323–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global Health Observatory (GHO) data: HIV/AIDS.

- 3.Shah ASV, Stelzle D, Lee KK, et al. Global Burden of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in People Living With HIV. Circulation 2018;138:1100–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bays HE. Adiposopathy is "sick fat" a cardiovascular disease? J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:2461–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buggey J, Longenecker CT. Heart fat in HIV: marker or mediator of risk? Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2017;12:572–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brener M, Ketlogetswe K, Budoff M, et al. Epicardial fat is associated with duration of antiretroviral therapy and coronary atherosclerosis. AIDS 2014;28:1635–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lo J, Abbara S, Rocha-Filho JA, et al. Increased epicardial adipose tissue volume in HIV-infected men and relationships to body composition and metabolic parameters. AIDS 2010;24:2127–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cerrato E, D'Ascenzo F, Biondi-Zoccai G, et al. Cardiac dysfunction in pauci symptomatic human immunodeficiency virus patients: a meta-analysis in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. Eur Heart J 2013;34:1432–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freiberg MS, Chang CH, Skanderson M, et al. Association Between HIV Infection and the Risk of Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction and Preserved Ejection Fraction in the Antiretroviral Therapy Era: Results From the Veterans Aging Cohort Study. JAMA Cardiol 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsue PY, Hunt PW, Ho JE, et al. Impact of HIV infection on diastolic function and left ventricular mass. Circ Heart Fail 2010;3:132–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Kindi SG, ElAmm C, Ginwalla M, et al. Heart failure in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: Epidemiology and management disparities. Int J Cardiol 2016;218:43–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah RV, Anderson A, Ding J, et al. Pericardial, But Not Hepatic, Fat by CT Is Associated With CV Outcomes and Structure: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franssens BT, Nathoe HM, Visseren FL, et al. Relation of Epicardial Adipose Tissue Radiodensity to Coronary Artery Calcium on Cardiac Computed Tomography in Patients at High Risk for Cardiovascular Disease. Am J Cardiol 2017;119:1359–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guaraldi G, Scaglioni R, Zona S, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue is an independent marker of cardiovascular risk in HIV-infected patients. AIDS 2011;25:1199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Longenecker CT, Jiang Y, Yun CH, et al. Perivascular fat, inflammation, and cardiovascular risk in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy. Int J Cardiol 2013;168:4039–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kristoffersen US, Lebech AM, Wiinberg N, et al. Silent ischemic heart disease and pericardial fat volume in HIV-infected patients: a case-control myocardial perfusion scintigraphy study. PLoS One 2013;8:e72066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raggi P, Zona S, Scaglioni R, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue and coronary artery calcium predict incident myocardial infarction and death in HIV-infected patients. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2015;9:553–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Packer M Epicardial Adipose Tissue May Mediate Deleterious Effects of Obesity and Inflammation on the Myocardium. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:2360–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paulus WJ, Tschope C. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:263–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagueh SF, Smiseth OA, Appleton CP, et al. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2016;29:277–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2015;28:1–39 e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alencherry B, Erem G, Mirembe G, et al. Coronary artery calcium, HIV and inflammation in Uganda compared with the USA. Open Heart 2019;6:e001046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox CS, Gona P, Hoffmann U, et al. Pericardial fat, intrathoracic fat, and measures of left ventricular structure and function: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2009;119:1586–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erqou S, Lodebo BT, Masri A, et al. Cardiac Dysfunction Among People Living With HIV. JACC: Heart Failure 2019;7:98–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okeke NL, Alenezi F, Bloomfield GS, et al. Determinants of Left Ventricular Hypertrophy and Diastolic Dysfunction in an HIV Clinical Cohort. J Card Fail 2018;24:496–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diaz-Zamudio M, Dey D, LaBounty T, et al. Increased pericardial fat accumulation is associated with increased intramyocardial lipid content and duration of highly active antiretroviral therapy exposure in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus: a 3T cardiovascular magnetic resonance feasibility study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2015;17:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee JJ, Pedley A, Hoffmann U, et al. Cross-Sectional Associations of Computed Tomography (CT)-Derived Adipose Tissue Density and Adipokines: The Framingham Heart Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5:e002545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Konishi M, Sugiyama S, Sato Y, et al. Pericardial fat inflammation correlates with coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 2010;213:649–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Antonopoulos AS, Sanna F, Sabharwal N, et al. Detecting human coronary inflammation by imaging perivascular fat. Science Translational Medicine 2017;9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Longenecker CT, Margevicius S, Liu Y, et al. Effect of Pericardial Fat Volume and Density on Markers of Insulin Resistance and Inflammation in Patients With Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection. Am J Cardiol 2017;120:1427–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.