Abstract

In the last two decades, metal−organic frameworks (MOFs) have attracted overwhelming attention. With readily tunable structures and functionalities, MOFs offer an unprecedentedly vast degree of design flexibility from enormous number of inorganic and organic building blocks or via postsynthetic modification to produce functional nanoporous materials. A large extent of experimental and computational studies of MOFs have been focused on gas phase applications, particularly the storage of low‐carbon footprint energy carriers and the separation of CO2‐containing gas mixtures. With progressive success in the synthesis of water‐ and solvent‐resistant MOFs over the past several years, the increasingly active exploration of MOFs has been witnessed for widespread liquid phase applications such as liquid fuel purification, aromatics separation, water treatment, solvent recovery, chemical sensing, chiral separation, drug delivery, biomolecule encapsulation and separation. At this juncture, the recent experimental and computational studies are summarized herein for these multifaceted liquid phase applications to demonstrate the rapid advance in this burgeoning field. The challenges and opportunities moving from laboratory scale towards practical applications are discussed.

Keywords: computations, liquid phase applications, metal−organic frameworks, nanoporous materials

There has been rapidly increasing interest to apply metal‐organic frameworks (MOFs) for liquid phase applications. Remarkable progress and significant advance in this field have been achieved over the last several years. Herein, the recent experimental and computational studies using MOFs for multifaceted liquid phase applications in energy, environmental and pharmaceutical sectors are summarized.

1. Introduction

The field of porous crystalline materials has received flourishing attention due to the possibilities to form well‐defined structures by molecular building blocks with spatial control over atomic scale.[ 1 ] In the controllable porous space of these materials, guest molecules exhibit intriguing properties significantly different from bulk phase, thus leading to a wide range of applications. As a typical class of porous crystalline materials, zeolites comprise tetrahedral SiO4 and AlO4 units connected via corner‐sharing oxygen atoms to form highly ordered pores and crystalline skeletons. Due to the restriction of tetrahedral skeletons, zeolites can be produced with a limited number of structures. Since the first natural zeolite (stilbite) discovered in 1756, currently there are only 240 zeolites of distinct framework topologies.[ 2 ] In the last two decades, metal−organic frameworks (MOFs) have emerged as a special class of porous crystalline materials.[ 3 ] In remarkable contrast to zeolites, MOFs can be synthesized from an extremely wide range of inorganic clusters (e.g., trigonal, tetrahedral, and octahedral) and organic linkers (e.g., carboxylates, imidazolates, and tetrazolates). More importantly, judicious selection of building blocks allows for readily tailoring MOF structures and functionalities in a rational manner. To date, over 100 000 MOFs have been synthesized with their crystal structures deposited in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre.[ 4 ] Not only their structural diversity and tailorability, but the unique features like framework flexibility and chirality make MOFs very attractive than other classes of porous materials. Therefore, MOFs have been identified as a topical area in materials science and technology, and considered as versatile materials for many important potential applications such as storage, separation, drug delivery, sensing and catalysis.[ 5 , 6 , 7 ]

In early years of development, MOFs were primarily examined for gas storage of low‐carbon footprint energy carriers (e.g., H2 and CH4),[ 8 , 9 ] as largely inspired by the unprecedented surface areas and pore volumes. With inherent similarity to the molecular sieve characteristics of zeolites, meanwhile, there was also a great interest to apply MOFs as adsorbents or membranes for chemical separation, particularly the separation of CO2‐containing gas mixtures.[ 10 , 11 ] Impressive performance in gas storage and separation was achieved by tailor‐made MOFs with various atomic structures, topologies networks, pore dimensions, as well as surface chemistries.[ 12 ] Recently, along with the traditional applications in gas phase, new promising avenues have emerged for MOFs including hydrocarbon separation, water treatment, solvent recovery, catalysis, luminescence, optics, thermal/mechanical/magnetic/electronic properties, etc.[ 13 ] Such evolution is clearly evidenced from Figure 1 based on the papers presented in the past five MOF conferences. In the 1st one (2010), 58% of papers were focused on gas phase applications and this percentage dropped to 32% in the 5th one (2018). By contrast, more papers appeared for new avenues, particularly liquid phase applications rose from 7% in 2010 to 24% in 2018.

Figure 1.

Percentage of papers presented at MOF conferences: MOF‐2010 (Marseille, France), MOF‐2012 (Edinburgh, UK), MOF‐2014 (Kobe, Japan), MOF‐2016 (California, USA), and MOF‐2018 (Auckland, New Zealand).

Liquids such as water, organic solvents and fuels are closely related to human activities and largely used in industries. In many applications, liquid phase operation is preferred over gas phase. For instance, heat‐sensitive compounds may be safely separated in a solution at room temperature, rather than being heated into gas or vapor. Many soluble compounds (e.g., amino acids, proteins, drugs, nucleic acids, antioxidants, carbohydrates, natural and synthetic polymers) can be dissolved in a solvent and purified, whereas gas phase separation is suitable for gaseous mixtures or volatile compounds.

One early application of MOFs in a liquid phase was the selective adsorption and inclusion of aromatic and non‐aromatic components (e.g., benzene, nitrobenzene, cyanobenzene and chlorobenzene) from solvents.[ 14 ] However, actual implementation for liquid phase applications was impeded by low stability of MOFs. Due to the relatively weak coordination bonds between metals and ligands, a large number of MOFs are chemically unstable in solvents or under harsh conditions. This is why the early studies for MOFs were primarily focused on gas phase, despite the presence of impressive porosity.[ 15 ] With the improved understanding towards metal‐ligand lability and MOF structural instability in water, acid/base and harsh solvent conditions, several strategies have been developed to design stable MOFs, particularly water stable MOFs. The strategies can be broadly categorized into de novo synthesis and postsynthetic modification. In de novo synthesis, hard/soft acid‐base principle is often used to choose the combination of metal‐ligand to reduce lability. For example, it is increasingly recognized that higher valence cations such as group‐IV metals can interact strongly with organic ligands; particularly zirconium‐based cluster is able to produce MOFs with superior hydrolytic, thermal and chemical stability. On the other hand, stable MOFs with low valence metals can be synthesized from nitrogen‐containing ligands such as imidazolates, pyrazolates, triazolates, and tetrazolates.[ 16 ] In postsynthetic modification, appropriate functional groups are usually incorporated into existing MOFs or the coordination bonds of certain unstable building units are modified to enhance strength. Such modification to synthesize stable MOFs is not easily achievable through de novo route.[ 17 ] Based on these strategies, more water‐ and solvent‐resistant MOFs have been successfully synthesized in the past several years. Therefore, as evidenced from the trend in Figure 1, there has been rapidly increasing interest in liquid phase applications.

As shown in Figure 2 , the potential liquid phase applications for MOFs are in a myriad range such as liquid fuel purification, aromatics separation, water treatment, solvent recovery, chemical sensing, chiral separation, drug delivery, biomolecule encapsulation and separation. It is worthwhile to note that some of these applications are beyond reach to other porous materials like zeolites. For example, drugs and biomolecules usually have diameters in a nanometer scale and are larger than the windows of most zeolites. Therefore, drug delivery and biomolecule encapsulation can hardly be achieved by zeolites; instead, biocompatible MOFs can be used. Moreover, the organic linkers of MOFs may exert favorable interactions with organic solvents, allowing for efficient solvent recovery. Asymmetric centers introduced into MOFs can be applied to enantioselective separation. Due to limited availability of pore size and inorganic nature, zeolites may not be appropriate for these specific applications. Moreover, MOFs offer an unprecedentedly large degree of tunability and structural diversity, as well as the wide range of chemical and physical properties. All these salient features facilitate the utilization of MOFs for liquid phase applications.

Figure 2.

Liquid phase applications of MOFs.

Compared with numerous reviews summarized for gas separation, there were only few reviews exclusively for liquid separation.[ 18 , 19 , 20 ] These reviews discussed experimental studies on MOFs for liquid separation, not for general liquid phase applications. In this review, we attempt to summarize the recent experimental studies for a wide variety of liquid phase applications in energy, environmental and pharmaceutical sectors, including liquid fuel purification, aromatics separation, water treatment, solvent recovery, chemical sensing, chiral separation, drug delivery, biomolecule encapsulation and separation. In addition, representative computational efforts are also discussed. With ever‐growing mathematical algorithms and physical resources, computational studies have become an invaluable tool in materials characterization, screening and design. By comprehensively and critically summarizing the current state of MOFs for liquid phase applications, this review will provide systematic overview and facilitate the rational development of new MOFs in this important field.

2. Energy Sector

In the chemical and petrochemical industries, hydrocarbon is usually produced as a mixture and required to be separated. Traditional technology for hydrocarbon separation is distillation due to its simplicity and maturity in operation. However, distillation is energy intensive, particularly for the separation of liquids with closely boiling points and not suitable for temperature‐sensitive compounds. Adsorption and membrane technologies using MOFs provide superior alternatives to distillation. The recent development using MOFs for liquid phase hydrocarbon separation is summarized here, including liquid fuel purification and aromatics separation.

2.1. Liquid Fuel Purification

Gasoline and diesel are commonly used liquid fuels for transportation. Though gasoline has approximately equal portion of aliphatic and aromatic components, the major component in diesel is aliphatic hydrocarbons. The presence of impurities like sulfur‐ and nitrogen‐containing compounds (NCCs and SCCs) adversely affect fuel efficiency and cause environmental pollution.[ 21 ] Moreover, these compounds can poison catalysts during combustion. Therefore, the impurities are required to be removed to produce cleaner liquid fuels. Hydrodenitrogenation and hydrodesulfurization are usually used to remove nonaromatic NCCs and SCCs, respectively. These techniques are less efficient for sterically hindered counterparts such as benzothiophene (BT), dibenzothiophene (DBT), 4,6‐dimethyldibenzothiophene (DMDBT), pyridines, and pyrroles.[ 22 ] As an alternative, desulfurization and denitrogenation by adsorption in porous materials have attracted considerable attention due to low operating temperature and pressure, and the capability to achieve ultraclean fuels affordably. Traditional porous materials including zeolites and activated carbons have been tested for liquid fuel purification; however, they lack fast adsorption kinetics and high capacity, thus not widely used. The most important task currently is to develop adsorbents that are able to remove NCCs and SCCs with high selectivity from complex hydrocarbon mixtures.

Table 1 lists the recent studies using MOFs for liquid fuel purification. Matzger's group examined the performance of five chemically diverse MOFs (HKUST‐1, UMCM‐150, MOF‐505, MOF‐5, and MOF‐177) for removing organosulfurs (BT, DBT, and DMDBT) in isooctane. These MOFs were found to exhibit excellent adsorption capacities, which are higher than NaY zeolite, indicating strong affinity between the frameworks and organosulfurs. UMCM‐150 and MOF‐505 have the highest affinity for DBT as evidenced in Figure 3 by the closest contact of DBT with UMCM‐150 and MOF‐505.[ 23 ] Moreover, they carried out packed‐bed breakthrough experiments to remove DBT and DMDBT in model and authentic diesels, respectively. Exceptional amounts of solutions were desulfurized before breakthrough point. This study demonstrates the practicality of MOFs for the desulfurization of liquid fuels. Even in the presence of competitive aromatic compounds, these MOFs could still selectively adsorb DBT and DMDBT, in contrast to zeolites and activated carbons.[ 24 ]

Table 1.

Liquid Fuel Purification

| Mixture | MOF | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| BT, DBT, DMDBT in iso‐octane | HKUST‐1, UMCM‐150, MOF‐505, MOF‐5, MOF‐177 | [ 23 ] |

| DBT, DMDBT in diesel | HKUST‐1, UMCM‐150, MOF‐505, MOF‐5, MOF‐177 | [ 24 ] |

| DBT, DMDBT in i‐octane | UMCM‐152, UMCM‐153 | [ 25 ] |

| DBT, DMDBT in iso‐octane | UMCM‐150 | [ 26 ] |

| Thiophene, tetrahydrothiophene in gasoline and diesel | Zn‐MOF, Cu‐DABCO‐MOF, Cu‐Iso‐MOF,Cu‐BTC | [ 27 ] |

| BT in n‐octane | MIL‐53(Al), MIL‐53(Cr), MIL‐47(V) | [ 28 ] |

| BT in n‐octane | CuCl2/MIL‐47 | [ 29 ] |

| BT in n‐octane | PWA‐Cu‐BTC | [ 30 ] |

| BT in n‐octane, toulene/n‐octane | CuCl2/V‐BDC, CuCl2/Al‐BDC, CuCl2/Cr‐BDC | [ 31 ] |

| BT in n‐octane, toulene/octane mixture | IL/MIL‐101 | [ 32 ] |

| BT, DBT in n‐octane | MOF dispersed in MIL‐100(Fe), CuBTC | [ 33 ] |

| Quinoline, indole in n‐octane, p‐xylene | MIL‐101(Cr) | [ 34 ] |

| Quinoline, indole in n‐octane, p‐xylene | PWA/MIL‐101(Cr) | [ 35 ] |

| Quinoline, indole in n‐octane, p‐xylene | GO/MIL‐101 | [ 36 ] |

| Quinoline, indole in n‐octane | CuCl/MIL‐100(Cr) | [ 37 ] |

| Quinoline, indole in n‐octane | AlCl3/MIL‐100(Fe) | [ 38 ] |

| Quinoline, indole, pyrrole, and methylpyrrole in n‐octane | UiO‐66, UiO‐66‐NH2 | [ 39 ] |

| Quinoline and indole in n‐otcane | UiO‐66‐NH‐SO3H, UiO‐66‐NH2 | [ 40 ] |

| Quinoline and indole in n‐octane | Polyaniline‐encapsulated MIL‐101 | [ 41 ] |

| Thiophene in naphtha | HKUST‐1, CPO‐27‐Ni, rho‐ZMOF, ZIF‐8, ZIF‐76 | [ 42 ] |

| BT, DBT in iso‐octane | [Cu(L)1/3(H2O)]⋅8 DMA | [ 43 ] |

| BT, DBT, 3‐MT in n‐octane | Cu‐BTC, Cu‐BDC, Cr‐BTC, Cr‐BDC | [ 44 ] |

| BT, DBT in isooctane | IFMC‐16 | [ 45 ] |

| Benzothiophene, benzothiazole, indole in isopropanol and heptane | MIL‐53 | [ 46 ] |

| DBT in benzene (aromatic oil), n‐octane (aliphatic oil), and mixed oil | MOF‐5 | [ 47 ] |

| DBT in n‐octane, DBT in benzene, p‐xylene, napthalene/n‐octane mixture | MIL‐101(Cr), PTA/MIL‐101(Cr) | [ 48 ] |

| Thiophene, BT, DBT in n‐octane | Fe3O4‐PAA‐MOF‐199 | [ 49 ] |

| N‐compounds in light cycle oil | MIL‐101(Cr) | [ 50 ] |

| Aliphatic C5‐diolefins, mono‐olefins and paraffins | MIL‐96 and Cu3(BTC)2 | [ 51 ] |

| Indole and carbazoles in toluene and heptane | MIL‐100(Fe, Cr, Al), MIL‐101(Cr), MIL‐47, MIL‐53, Cu3(BTC)2, CPO‐27(Ni,Co) | [ 52 ] |

| Indole and 1,2‐dimethylindole in heptane | MIL‐100(Al, Cr, Fe,V) | [ 53 ] |

| Pyridine, pyrrole, quinoline and indole in n‐octane | MIL‐96(Al), MIL‐53(Al), MIL‐101(Cr) | [ 54 ] |

| Quinoline, indole, DBT,4,6‐DMDBT, naphthalene in n‐octane | MIL‐101(Cr), MIL‐100(Fe), Cu‐BTC | [ 55 ] |

| Thiophene in n‐octane | Cu‐BTC or MIL‐101/PDMS MMM, Ag+@COF‐Pebax | [ 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 ] |

| Thiophene in iso‐octane | Zeolite beta @ HKUST‐1 | [ 61 ] |

| Methanol/water | Cu(R‐GLA‐Me)(4,4’‐Bipy)0.5 | [ 62 ] |

| C1‐C5 alcohols/water | ZIF‐8 | [ 63 ] |

| Biobutanol/fermentation broth | ZIF‐8 | [ 64 ] |

| 2,5‐dimethylfuran and 2‐methylfuran in butanol | ZIF‐7, ZIF‐8, and ZIF‐71 | [ 65 ] |

| Methanol, ethanol/water | Cu2(bza)4(pyz)/PDMS membrane | [ 66 ] |

| C2‐C5 alcohols/water | ZIF‐8/PMPS membrane | [ 67 ] |

| TP, BT and DBT | Cr‐MIL‐101‐SO3Ag | [ 68 ] |

| BT in n‐octane | IL@MIL‐101 | [ 69 ] |

| DBT, BT | MOF‐74 | [ 70 ] |

| Ethanol, t‐butanol, ester/water | MIL‐53 and MIL‐96 membranes | [ 71 ] |

| Alcohols/water, dimethyl carbonate/methanol | ZIF‐71 membrane | [ 72 ] |

| Butanol/water | ZIF‐8‐PDMS membrane | [ 73 ] |

| Ethanol/water | ZIF‐71/PDMS MMM | [ 74 ] |

| Ethanol/water | Sm‐DOBDC membrane | [ 75 ] |

| Methanol/MTBE | UiO‐66 membrane | [ 76 ] |

| Ethanol/water | Na‐rho‐ZMOF and Zn4O(bdc)(bpz)2 | [ 77 ] (sim.) |

| Ethanol/water | ZIF‐8, ‐25, ‐71, ‐90, ‐96, and ‐97 | [ 78 ] (sim.) |

| Ethanol/water | ZIF‐68, ‐69, ‐78, ‐79, and ‐81 | [ 79 ] (sim.) |

| Glycerol/methanol | IRMOF‐1 | [ 80 ] (sim.) |

Figure 3.

Locations of a DBT molecule in a) MOF‐177, b) MOF‐5, c) UMCM‐150, d) HKUST‐1, and e) MOF‐505. Reproduced with permission.[ 23 ] Copyright 2008, American Chemical Society.

Khan and Jhung systematically investigated the removal of NCCs and SCCs from liquid fuels by loading inorganic salts into MOFs as additional adsorption sites. Particularly, CuCl2 loaded MIL‐47 showed remarkable adsorption capacity for BT through the π‐complexation with Cu+ resulted from the reduction of loaded Cu2+ ions.[ 29 ] Later, other compounds (e.g., AlCl3 and phosphotungstic acid) were also loaded. A stable Cu(I)‐compound [(Cu2(pyrazine)2(SO4)(H2O)2)n, denoted as CP] was employed to form composites in MIL‐100(Fe) and CuBTC. The prepared CP/MIL‐100(Fe) and CP/CuBTC composites were examined for the adsorptive removal of SCCs. The adsorption capacity of BT was found to increase with increasing CP content and the highest capacity was observed at a medium CP content denoted as CP(m)/MIL‐100(Fe). At the highest CP content, the capacity of BT was reduced as a result of an excessive degree of pore blocking. High adsorption capacity was also seen for DBT in CP(m)/MIL‐100(Fe). This study demonstrates the beneficial utilization of added active sites in porous MOFs for adsorption.[ 33 ] Jhung and co‐workers further used MOF‐based composites to remove NCCs from liquid fuels. Specifically, polyaniline (pANI) encapsulated MIL‐101(Cr) was prepared via a ship‐in‐bottle strategy and applied in the adsorption of both basic quinoline and neutral indole. Record high adsorption capacities were obtained, as shown in Figure 4 , attributed to hydrogen bonding, acid–base interaction and cation−π interaction between the composites and adsorbates. It was suggested that protonated pANI‐encapsulated MOFs (P‐pANI) could be a new type of adsorbents for very efficient removal of NCCs from liquid fuels.[ 41 ]

Figure 4.

a) Schematic of N‐compounds adsorption in pANI‐loaded MIL‐101, b) adsorption isotherms of indole in MIL‐101 and P‐pANI‐5. Reproduced with permission.[ 41 ] Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society.

De Vos's group investigated and compared the separation mechanisms of aliphatic C5‐diolefins, mono‐olefins and paraffins in two MOFs (MIL‐96 and Cu3(BTC)2) and two zeolites (CHA and LTA). These hydrocarbons represent a typical feed produced by a steam cracker. MIL‐96 and CHA were found to adsorb trans‐piperylene preferably from a mixture of three C5‐diolefin isomers with high separation factor. The capacity was higher compared with 5A zeolite as attributed to more efficient packing of trans‐isomer. In addition, CHA could separate cis‐piperylene and isoprene due to the size exclusion of branched isomers. Thus, CHA was shown suitable candidate for separating three C5‐diolefin isomers, as well as separating linear from branched mono‐olefins and paraffins. Cu3(BTC)2 was demonstrated to be able to separate C5‐olefins from paraffins. Interestingly, MIL‐96 was revealed to be the only material that could separate three C5‐diolefin isomers from C5‐mono‐olefins and paraffins. Based on these observations, a flow scheme illustrated in Figure 5 was devised for the separation of C5‐cut from a steam cracker. By a combination MOFs and zeolites, C5‐hydrocarons could be completely separated.[ 51 ]

Figure 5.

Flow scheme for the separation of C5‐cut from a steam cracker. Reproduced with permission.[ 51 ] Copyright 2010, American Chemical Society.

In addition to being used as adsorbents, MOFs have been used as nanofillers into polymer membranes for the fabrication of mixed‐matrix membranes (MMMs). Cao and co‐workers added 8 wt% of Cu3(BTC)2 in polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) membranes and tested for pervaporative removal of thiophene from model gasoline. The MOF particles were found to reduce permeation resistance and facilitate the selective transport of thiophene. In comparison with pristine PDMS membranes, the flux and enrichment factor were increased by 100% and 75%, respectively.[ 56 ] In a separate study, MIL‐101(Cr)/PDMS membranes with 6% loading supported on polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) were examined for the desulfurization of model gasoline and thiophene/n‐octane mixture. Compared with the pristine membrane, increase of 136% and 38% was observed in flux and enrichment factor, respectively. The packing of PDMS chains was intervened by MIL‐101(Cr) particles, thus resulting in larger fractional free volume and enhanced flux.[ 58 ] They further synthesized hybrid membranes of amine‐functionalized NH2‐MIL‐125(Ti) loaded with Ag+, coined as Ag+@NH2‐MIL‐125(Ti), and investigated for pervaporative desulfurization. It was found that the immobilized Ag+ could form reversible π‐complexation with thiophene and attain facilitated thiophene‐selective transport. On the other hand, the presence of Ag+ reduced the effective pore size and increased the diffusion selectivity of thiophene via a sieving mechanism illustrated in Figure 6a. As a result, Pebax membrane with 1.0 wt% Ag+@NH2‐MIL‐125(Ti) exhibited an increase in flux and enrichment factor by 34% and 33%, respectively. As shown in Figure 6b, Pebax‐Ag+@NH2‐MIL‐1.0 was found to outperform over many other membranes reported in the literature. This study recommends the integration of multiple transport mechanisms by using MOFs as nanofillers to achieve superior separation performance.[ 60 ]

Figure 6.

a) Thiophene sieving mechanism, b) pervaporative desulfurization performance of Pebax‐Ag+@NH2‐MIL‐1.0/polysulfone hybrid membrane and other membranes. Reproduced with permission.[ 60 ] Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society.

The depletion of fossil fuels has sparked enormous interest to develop alternative energy resources such as renewable biofuels. Compared with conventional fuels, biofuels are environmentally benign and carbon neutral with less emission of gaseous pollutants. As‐produced biofuels (e.g., bioethanol and biobutanol) contain a large amount of water and it is crucial to separate alcohols and water. Due to the formation of low‐boiling azeotropes, however, complete removal of water by distillation is not feasible. Moreover, alcohols are the minor components after fermentation and the separation of alcohols via distillation is energy intensive. In this context, a number of MOFs have been examined as adsorbents for biofuel purification.

Denayer and co‐workers used zeolitic imidazolate framework‐8 (ZIF‐8) for the adsorption of methanol, ethanol, propanol, butanol and acetone from aqueous mixtures. High capacity of butanol was observed, which significantly exceeds those in active carbon and silicalite. Concentrated butanol could be obtained by the regeneration of adsorption column with methanol and mild heating.[ 63 ] Subsequently, they conducted batch and breakthrough measurements of ZIF‐8, active carbon, silicalite and SAPO‐34 for biobutanol purification. Other compounds present in a real ABE (acetone‐butanol‐ethanol) fermentation were found to have an insignificant effect on the adsorption of butanol in ZIF‐8, while SAPO‐34 exhibited high affinity for water and ethanol, but not for butanol. This study suggests that the combination of ZIF‐8 and SAPO‐34 might be attractive for the recovery and purification of biobutanol by adsorption.[ 64 ]

Recently, Nair and co‐workers utilized MOFs in a simulated moving bed (SMB) process to demonstrate the purification of solvents (e.g., butanol) and the concurrent production of furanics (e.g., 2,5‐dimethylfuran, 2,5‐DMF) from multicomponent biofuel reactor exit streams. Via adsorption measurements and ideal adsorbed solution theory (IAST) predictions, ZIF‐8 was revealed to have particularly favorable furan‐selective behavior. Preferable adsorption of DMF was verified by liquid phase breakthrough measurements as shown in Figure 7a,b. An iterative refinement of multicomponent adsorption model as well as detailed dynamic SMB simulation, shown Figure 7c,d, were performed for a realistic multicomponent feed stream until the process converging to satisfy the extract and raffinate purity and recovery requirements. The ZIF‐based SMB was predicted to reach a productivity similar to those of current SMB processes for the production of petrochemical aromatics such as p‐xylene.[ 65 ]

Figure 7.

a,b) Typical result of a liquid breakthrough measurement using a binary feed containing DMF (green) and butanol (blue). Red: ZIF‐8. Green: ZIF‐71. Black: UiO‐66. Blue: FA‐UiO‐66. The solid curves represent IAST predictions. c,d) SMB and simulated liquid composition profiles along the axial position coordinate using ZIF‐8 and multicomponent Langmuir adsorption model. Reproduced with permission.[ 65 ] Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society.

Meanwhile, MOF‐based membranes have been investigated for biofuel purification. By dispersing [Cu2(bza)4(pyz)] (bza = benzoate, pyz = pyrazine) into PDMS to form a MMM, Takamizawa et al. attempted to separate alcohol/water mixtures by pervaporation. The membrane showed effective separation capability with separation factors of 5.6 and 4.7 for methanol/water and ethanol/water mixtures, respectively.[ 66 ] Similarly, Liu et al. prepared a MMM by doping ZIF‐8 in a silicone rubber polymethylphenylsiloxane (PMPS) membrane and applied for the pervaporation separation of alcohols/water mixture. Both flux and selectivity were found to increase simultaneously with increasing ZIF‐8 and higher than those in the pristine PMPS membrane. Furthermore, the separation performance was enhanced with the carbon number of alcohols due to the increased adsorption capacity and selectivity.[ 67 ]

Instead of MMMs, Jin and co‐workers developed a facile reactive seeding method to prepare continuous MIL‐53 and MIL‐96 membranes on an alumina support. As illustrated in Figure 8 , the porous support acted as an inorganic source reacting with organic precursor to grow a seeding layer. The prepared membranes were tested in pervaporation to separate the mixtures of organics (ethanol, t‐butanol and ester)/water. High selectivity was obtained and the membranes exhibited good stability.[ 71 ] Dong and Lin prepared an organophilic ZIF‐71 membrane on a porous ZnO substrate for the pervaporation separation of alcohol/water and dimethyl carbonate (DMC)/methanol mixtures. Good performance was observed particularly for the separation of DMC from methanol, confirming the gate opening effect of ZIF‐71. This study demonstrates that ZIF‐71 membrane is promising for the separation of not only organics/water but also organics/organics mixtures.[ 72 ]

Figure 8.

Reactive seeding method to prepare MIL‐53 membrane on an alumina support. Reproduced with permission.[ 71 ] Copyright 2011, Royal Society of Chemistry.

There were a few simulation studies reported on biofuel purification. Jiang and co‐workers simulated the purification of ethanol/water mixtures in Na‐rho‐ZMOF and Zn4O(bdc)(bpz)2 membranes at both pervaporation (50 °C) and vapor permeation (100 °C) conditions. In hydrophilic Na‐rho‐ZMOF, water was found to be preferentially adsorbed over ethanol due to its strong interaction with the anionic framework and nonframework Na+ ions, and the adsorption selectivity of water/ethanol was higher at a lower composition of water. With increasing water composition, the diffusion selectivity of water/ethanol was observed to increase. In contrast, ethanol was adsorbed more in hydrophobic Zn4O(bdc)(bpz)2 as attributed to the favorable interaction with methyl groups, and the adsorption selectivity of ethanol/water was higher at a lower composition of ethanol. With increasing ethanol composition, the diffusion selectivity of ethanol/water increased slightly. As demonstrated in Figure 9 , the maximum permselectivity in Na‐rho‐ZMOF is about 12 by vapor permeation and Na‐rho‐ZMOF is preferable for biofuel dehydration. In Zn4O(bdc)(bpz)2, the maximum permselectivity is 75 by pervaporation and Zn4O(bdc)(bpz)2 is promising for biofuel recovery. This study presents microscopic insight into the separation of water/ethanol mixtures in hydrophilic and hydrophobic MOF membranes, imparts that hydrophobic MOF is superior to hydrophilic counterpart for biofuel purification.[ 77 ]

Figure 9.

Permselectivities for water/ethanol mixtures in Na‐rho‐ZMOF and Zn4O(bdc)(bpz)2. Reproduced with permission.[ 77 ] Copyright 2011, Royal Society of Chemistry.

They subsequently simulated the adsorption and separation of ethanol/water mixtures in six ZIFs (ZIF‐8, ‐25, ‐71, ‐90, ‐96, and ‐97) with different functional groups. The adsorption isotherms of pure ethanol and water were predicted to agree fairly well with experimental data. Interestingly, the atomic charges in asymmetrically functionalized ZIF‐90, ‐96, and ‐97 were revealed to have important effect on adsorption, in remarkable contrast to symmetrically functionalized ZIF‐8, ‐25, and ‐71. The framework hydrophobicity as well as cage size were determined to govern ethanol/water selectivity, with ZIF‐8 exhibiting the highest selectivity among the six ZIFs.[ 78 ] Later, a series of isoreticular ZIFs (ZIF‐68, ‐69, ‐78, ‐79, and ‐81) with GME topology but different organic linkers were also examined as adsorbents for ethanol/water separation. Among the five ZIFs, ZIF‐79 with hydrophobic –CH3 groups was shown to possess the highest adsorptive selectivity.[ 79 ] These simulation efforts provide microscopic insights into the adsorption‐based separation of ethanol/water mixtures and would facilitate the development of new MOFs for biofuel purification.

To better understand biofuel/biochemical processing in a representative catalytic cycle, Li et al. conducted a simulation study on the adsorption and diffusion of glycerol/methanol mixtures in IRMOF‐1. The liquid mixtures were assumed to be ideal solutions and the Raoult's Law was used to estimate the fugacity of each component. The presence of a small amount of methanol was found to promote the adsorption of glycerol. The diffusion of glycerol was not affected by a low concentration of methanol, but enhanced with increasing methanol concentration. However, methanol diffusivity was found to be is a complex due to the interplay between the interaction with IRMOF‐1 framework and intermolecular steric effect.[ 80 ]

As discussed above, the application of MOFs for liquid fuel purification was first tested by adsorption and later by membrane operation. Majority of the studies listed in Table 1 were to explore MOFs with various textural properties and interaction sites. When used as adsorbents, MOFs are generally superior to other porous materials because of higher adsorption capacities, more selective and easier regeneration. This is attributed to the combination of specific interactions such as acid–base interaction, π–π complexation, van der Waals force, as well as H‐bonding with active sites in MOFs. The general trend for adsorption selectivity in MOFs is NCCs > SCCs > aromatics > aliphatics. MOF‐based membranes are relatively less investigated for liquid fuel purification. Integration of multiple transport mechanisms is revealed to be critical for membrane separation of compounds with similar properties. For biofuel purification, however, hydrophobic/hydrophilic interactions dominate membrane performance. In general, MOFs with unsaturated metal nodes offer an additional route for incorporating metals to facilitate interaction and permeation.

2.2. Aromatics Separation

While the above is focused on the purification of aliphatic liquid fuels, the separation of aromatics has also received considerable interest, particularly on xylenes and related aromatics (e.g., ethylbenzene and styrene). With an annual production of several million tons, xylenes are produced by the catalytic reforming of crude oil.[ 81 ] After catalytic reforming, xylenes exist as part of BTEX aromatics (benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylenes) in a colorless liquid state. Xylenes have three isomers namely p‐, o‐, and m‐xylene, and each isomer is useful as a raw material for the manufacturing of various high‐value added chemicals and polymers;[ 82 ] therefore, it is crucial to separate these aromatics. Crystallization and adsorption are two main processes industrially practiced for aromatics separation. Between these two, adsorption is preferred because of a larger production rate and a significantly higher recovery at a lower cost. One major limitation with the industrially used adsorbents (BaX and KBaY) is the selectivity of p‐ over m‐xylene is not sufficiently high. Improving this selectivity is of paramount interest and industrial relevance.

Table 2 summarizes the studies on aromatics separation using MOFs as adsorbents or membranes. Early studies were conducted notably by De Vos and co‐workers. Among MIL‐47, MIL‐53, and Cu3(BTC)2 with similar pore aperture size, MIL‐47 was identified through breakthrough and chromatographic experiments to possess highest selectivity for the separation of C8 alkylaromatics (xylenes and ethylbenzene).[ 83 ] They also combined batch, pulse chromatographic and breakthrough experiments with MIL‐53 to examine the selective adsorption of C8, C9, and C10 alkylaromatics (xylenes, ethylbenzene, ethyltoluenes and cymenes). MIL‐53 displayed a pronounced preference for ortho‐isomers from a feed of alkylaromatic isomers and appeared to be more effective to host large ethyltoluenes and cymenes than MIL‐47.[ 84 ] Similar study was reported for the separation of olefins, alkylnaphthalenes and dichlorobenzenes in MIL‐47, MIL‐53 and Cu3(BTC)2. While Cu3(BTC)2 showed a remarkable preference for cis‐olefins over trans‐olefins via π‐complexation on its open metal sites, both MIL‐47 and MIL‐53 could separate 1,4‐dimethylnaphthalene from other alkylnaphthalene isomers, as well as p‐ and m‐dichlorobenzene. For alkylnaphthalenes, enthalpic interaction was revealed as an important factor governing selectivity; however, packing effect might dominate the selectivity of dichlorobenzenes.[ 86 ] In a follow‐up study, the separation of ethylbenzene (EB)/styrene (St) on Cu3(BTC)2 was investigated to demonstrate the role of specific interactions between the π‐electrons of aromatic compounds and Cu2+ sites (Figure 10a). Figure 10b shows the breakthrough elution profiles of EB and St with a separation factor of ≈ 2. A roll‐up‐effect was also observed due to the displacement of less preferred EB by more strongly adsorbing St.[ 89 ] They also examined the capability of three MOFs (MIL‐125, MIL‐125‐NH2 and CAU‐1‐NH2) for the separation of xylenes, ethyltoluenes and cymenes dissolved in heptane. Para‐selective adsorption was observed in the three MOFs, particularly the selectivity of p‐cymene over m‐cymene was measured to be >109 in MIL‐125‐NH2. The experimental data were in accord with simulation predictions; however, the simulations were conducted in a vapor phase, not a full representation of liquid separation.[ 91 ]

Table 2.

Aromatics Separation

| Aromatics | MOF | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Xylenes, ethylbenzene | MIL‐47, MIL‐53, Cu3(BTC)2 | [ 83 ] |

| Xylenes, ethylbenzene, ethyltoluenes, cymenes | MIL‐53 | [ 84 ] |

| Xylenes, ehtyltoluenes, dichlorobenzenes, toluidines, cresols | MIL‐47 | [ 85 ] |

| Alkylnaphthalenes, dichlorobenzenes | MIL‐47, MIL‐53, Cu3(BTC)2 | [ 86 ] |

| Ethylbenzene/styrene, p‐ethyltoluene/p‐methylstyrene | Cu3(BTC)2/silica composites | [ 87 ] |

| Ethylbenzene, styrene, toluene, o‐xylene | MIL‐47, MIL‐53 | [ 88 ] |

| Ethylbenzene/styrene, vinyltoluenes/ethyltoluenes | Cu3(BTC)2 | [ 89 ] |

| Methylnaphthalenes, dimethylnaphthalene, naphthalene | Cu2(bdc)2(dabco) | [ 90 ] |

| Xylenes, ethyltoluenes, cymenes | MIL‐125, MIL‐125‐NH2, CAU‐1‐NH2 | [ 91 ] |

| n‐propylbenzene, cumene | MIL‐47 | [ 92 ] |

| BTEX | MIL‐53 | [ 93 ] |

| Ethylbenzene, p‐xylene, o‐xylene | MIL‐53(Al) | [ 94 ] |

| Xylenes batch adsorption | Al‐MOF, CAU‐13 | [ 95 ] |

| C8 alkyaromatics, dihydroxybenzene isomers, butanol isomers | Cu(CDC) | [ 96 ] |

| cis/trans‐1,3‐dimethylcyclohexane and 4‐ethylcyclohexanol | MIL‐125(Ti) | [ 97 ] |

| Xylenes, ethylbenzene, dichlorobenzene, chlorotoluenes, styrene | MIL‐101 | [ 98 ] |

| Xylenes, dichlorobenzene, chlorotoluenes, toluene, naphthalene, anthracene, phenanthrene, pyrene, etc. | MIL‐53 | [ 99 , 100 ] |

| Nitroaniline, aminophenol, naphthol isomers, sulfadimidine, and sulfanilamide | MIL‐101(Cr) | [ 101 ] |

| BTE, naphthalene and 1‐chloronaphthalene; aniline, acetanilide, 2‐nitroaniline and 1‐naphthylamine, isomers of chloroaniline or toluidine | MIL‐100 | [ 102 ] |

| Neutral polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, acetanilide, 4‐fluoroaniline, 2‐nitroaniline, 1‐naphthylamine, resorcinol, m‐cresol, 2,6‐dimethylphenol, 2,6‐dichlorophenol, 1‐naphthol, 1‐methylnaphthalene, 1‐chloronaphthalene | UiO‐66‐poly(MAA‐co‐EDMA) | [ 103 ] |

| Endocrine‐disrupting chemicals, pesticides | ZIF‐8/silica | [ 103 ] |

| Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, phenols, anilines | COF TpPa‐MA | [ 104 ] |

| Xylene, chlorotoluene and cymene | MIL‐101(Cr) poly(BMA‐EDMA) | [ 105 ] |

| Benzene, ehtylbenzene, styrene, naphthalene, anthracene, phenanthrene, pyrene | MOF‐5, Cu3(BTC)2 | [ 106 ] |

| Ethylcinnamate, styrene, n‐heptane, i‐octane, dichloromethane | MOF‐5, Cu3(BTC)2, MIL‐101, DUT‐5, 6, 7, 9, ZIF‐8, Zn4O(btb)2, Zn2(bdc)2(dabco) | [ 107 ] |

| Xylenes | UiO‐66 | [ 108 ] |

| Xylenes | ZIF‐8 | [ 109 ] |

| 3ʹ‐hydroxyacetophenone, 3‐(1‐hydroxy phenyl) ethanol, 3‐[1‐(methylamino)ethyl] phenol, 3‐[1‐(dimethylamino)ethyl] phenol | HKUST‐1, MIL‐47, ZIF‐8 | [ 110 ] |

| Ethylbenzene, styrene | HKUST‐1 | [ 111 ] |

| Substituted benzenes and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons | UiO‐66 | [ 112 ] |

| Xylene, dichlorobenzene, chlorotoluene and nitroaniline isomers | MIL‐53 | [ 113 ] |

| n‐hexane, benzene, mesitylene | ZIF‐8 membrane | [ 114 ] |

| Xylene isomers | Zn2(BDC)2DABCO membrane | [ 115 ] |

| p‐xylene, o‐xylene | MOF‐5 membrane | [ 116 ] |

| Toluene, xylene, and 1,3,5‐triiso propylbenzene | MOF‐5 membrane | [ 117 ] |

| Toluene/n‐heptane, benzene/cyclohexane | MOP/W3000 MMM | [ 118 ] |

| Toluene/n‐heptane | Cu3(BTC)2/PVA MMM | [ 119 ] |

| Toluene/n‐heptane, benzene/cyclohexane | [MOP‐X, X = SO3NanHm, OH and tBu]/W3000 | [ 120 ] |

| Toluene/iso‐octane, benzene/cyclohexane, toluene/cyclohexane and toluene/n‐heptane | Co(HCOO)2/ PEBA MMM | [ 121 ] |

| Substituted benzenes and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons | UiO‐66‐NH2,UiO‐67 | [ 122 ] |

| Divinylbenzene and ethylvinylbenzene isomers | MIL‐53, MIL‐100 | [ 123 ] |

| Nitrobenzenes, nitrotoluenes, triphenyl benzene and tris(4‐bromobenzyl)benzene | UMCM‐310 | [ 124 ] |

| Cyclohexene or benzene from cyclohexane | HKUST‐1‐silica composite | [ 125 ] |

| C8‐isomers, dichlorobenzene isomers, styrene and ethylbenzene | UiO‐67/silica composite | [ 126 ] |

| Xylenes and ethylbenzene | Co2(dobdc), Co2(m‐dobdc) | [ 127 ] |

| Xylenes | MIL‐101 | [ 128 ] (sim.) |

| Xylenes | 14 MOFs | [ 129 ] (sim.) |

| Xylenes | MIL‐53(Al) | [ 130 ] (exp./sim.) |

| Xylenes | 2500 MOFs | [ 131 ] (sim./exp.) |

| Xylenes | MIL‐160 on PDA‐modified α‐Al2O3 support | [ 132 ] (exp./sim.) |

Figure 10.

a) Ethylbenzene (EB)/styrene (St) separation on Cu3(BTC)2. b) breakthrough elution profiles of EB and St. Reproduced with permission.[ 89 ] Copyright 2011, American Chemical Society.

Based on high‐performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), Yang and Yan applied slurry‐packed MIL‐101 column for the separation of xylenes, ethylbenzene, dichlorobenzene, chlorotoluenes and styrene. MIL‐101 was found to offer high affinity for ortho‐isomer, allowing fast and selective separation of isomers as shown in Figure 11 . For xylenes, dichlorobenzene and chlorotoluenes, the separation was controlled by entropy effect; while enthalpy change played a dominant role in ethylbenzene and styrene.[ 98 ] Subsequently, they used MIL‐53 as a stationary phase and explored the separation of xylenes, dichlorobenzene, chlorotoluenes, toluene, naphthalene, anthracene, phenanthrene and pyrene, as well as polar analytes. High resolution and good precision were obtained and the effects of mobile phase composition, injected sample mass and temperature were examined. The great potential of HPLC separation using MOF‐packed columns was envisioned from the combined mechanisms of size‐exclusion, shape selectivity and hydrophobicity.[ 99 , 100 ]

Figure 11.

HPLC chromatograms on MIL‐101 slurry‐packed column for the separation of a) xylenes and ethylbenzene b) dichlorobenzenes. Reproduced with permission.[ 98 ] Copyright 2011, American Chemical Society.

Matzger and co‐workers evaluated MOF‐5 and Cu3(BTC)2 for the shape and size selective separation of benzene, ehtylbenzene, styrene, naphthalene, anthracene, phenanthrene, pyrene, 1,3,5‐triphenylbenzene and 1,3,5,‐tris(4‐bromophenyl)benzene. Excellent performance was achieved based on a combination of adsorption and molecular sieving.[ 106 ] Adsorption of ethyl cinnamate and styrene from solvents was reported by Henschel et al. in various MOFs such as MOF‐5, Cu3(BTC)2, MIL‐101, DUT‐5,6,7,9, ZIF‐8, Zn4O(btb)2, and Zn2(bdc)2(dabco). They found that adsorption capacity was strongly dependent of framework chemistry, pore size and shape, as well as pore volume. Additionally, the size and polarity of solvent also appeared to have significant effects.[ 107 ] UiO‐66 was studied by Moreira et al. for the separation of xylenes using n‐heptane as an eluent. By pulse experiment, UiO‐66 was shown to preferentially adsorb o‐xylene. From binary and multicomponent breakthrough experiments, the selectivities were determined to be 1.8 and 2.4 for o‐xylene over m‐xylene and p‐xylene, respectively.[ 108 ] Peralta et al. presented the separation of xylene isomers in ZIF‐8 on the basis of molecular sieving mechanism. The highest capacity was seen for p‐xylene because of the smallest size, whereas o‐xylene with the largest size exhibited the least capacity. The rate of adsorption was also governed by the size of xylene, decreasing from p‐ to m‐ and to o‐xylene. In liquid phase breakthrough experiments, the separation efficiency was lower compared with that in gas phase. The quite dispersed breakthrough fronts indicated slow diffusion of xylenes into the sodalite cage of ZIF‐8. In addition, structural analysis suggested that the diffusion might occur via the transitory deformation of pore aperture in ZIF‐8.[ 109 ]

In addition to adsorptive and chromatographic separation, recent endeavor has applied MOF membranes for aromatics and aromatic/aliphatic mixtures. Caro and co‐workers prepared a thin‐film composite ZIF‐8 membrane on α‐Al2O3 support with ZIF‐8 layer of about 15 µm thickness continuously and densely grown. The membrane was evaluated for the pervaporation separation of n‐hexane/benzene and n‐hexane/mesitylene mixtures. The measured separation factor was lower than the predicted ideal permselectivity for n‐hexane/benzene as the mobile component n‐hexane was blocked by less mobile benzene. For n‐hexane/mesitylene, however, n‐hexane flux was increasingly reduced by pore entrance blocking with increasing mesitylene concentration.[ 114 ] Kang et al. synthesized a continuous‐growth Zn2(BDC)2DABCO membrane on a porous SiO2 substrate. To prepare MOF membrane by a second growth approach, as illustrated in Figure 12 , the surface of porous SiO2 was first modified with a linker 3‐aminopropyl‐triethoxysilane (APTES). The coordination of NH2 groups in APTES and zinc sites in the seed crystals increased the binding force between membrane and support. The membrane performance for the separation of xylene isomers was investigated. In contrast with zeolite membrane, this MOF membrane showed greater permeability for o‐xylene and m‐xylene with larger kinetic diameters due to the selective adsorption on the framework.[ 115 ]

Figure 12.

(Top) Zn2(BDC)2DABCO membrane preparation by a secondary growth approach. (Bottom) Cross‐section SEM image and EDS map of Zn2(BDC)2DABCO membrane grown after four cycles. Reproduced with permission.[ 115 ] Copyright 2013, Elsevier.

On the other hand, Li and co‐workers embedded soluble metal‐organic polyhedral (MOPs) into W3000 polymer to produce hybrid membranes for the PV separation of aromatic/aliphatic mixtures. For toluene recovery from its equimolar n‐heptane solution, a separation factor of 19.0 and a flux of 220.5 g m−2 h−1 were obtained at 4.8 wt% MOP loading and comparable with other reported membranes. As illustrated in Figure 13a, the embedding of MOP into W3000 could create preferential pathways for toluene due to high affinity of the coordinative unsaturated sites or π‐bond sites in MOPs. Moreover, the cavities of MOP were blocked by adsorbed toluene on these active sites located near MOP pore windows, thus restricting the entrance of n‐heptane even though n‐heptane is smaller than toluene. This resulted in increase of both flux and separation factor with increasing MOP loading. It was found that toluene transport favored through W3000 layer due to the presence of polar groups in MOP. Overall, the separation performance of hybrid MOP/W3000 membranes were significantly improved.[ 118 ] Subsequently, by using Cu3(BTC)2 as a filler in poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA), another MOF/polymer hybrid membrane was prepared and tested for the separation of 50 wt% toluene/n‐heptane mixtures through pervaporation. The separation factor and flux were improved upon comparison with pristine PVA membrane, specifically, from 8.9 and 14 g m−2 h−1 to 17.9 and 133 g m−2 h−1, respectively. The transport mechanism of permeating components in the selective layer of Cu3(BTC)2/PVA membrane was proposed as shown in Figure 13b. Presumably, the empty 3d‐orbitals of Cu2+ ion could contribute to d‐π conjugation interaction between the unsaturated metal ion and aromatic molecule, which resulted in a solubility difference relative to aliphatic compounds in the membrane. Furthermore, the selective layer in Cu3(BTC)2/PVA might bind toluene more strongly than n‐heptane, thus improving separation performance.[ 119 ]

Figure 13.

Toluene/n‐heptane separation through a) MOP/W3000, b) Cu3(BTC)2/PVA hybrid membranes. a) Reproduced with permission.[ 118 ] Copyright 2014, Royal Society of Chemistry. b) Reproduced with permission.[ 119 ] Copyright 2015, Elsevier.

The MOP/W3000 and Cu3(BTC)2/PVA hybrid membranes by Li and co‐workers[ 118 , 119 ] showed better separation capability than the pristine polymer counterparts; nevertheless, their performance was found not always improved upon increasing MOF loading. To provide in‐depth understanding, they further synthesized Co(HCOO)2/polyether‐block‐amide (PEBA) membranes for the separation of toluene and n‐heptane mixtures. When Co(HCOO)2 loading was increased from 1 to 8 wt%, the separation factor initially increased and then decreased, while the flux kept increasing; at a loading of 4 wt%, the highest separation factor was achieved. When the loading was low, Co(HCOO)2 particles would contribute to the enhanced interaction between toluene and membrane, and increase fractional free volume. Thus the flux and separation factor were increased. At excessive loading, however, the particles would aggregate and form certain defects on the membrane surface. Consequently, the flux was increased while the separation factor was decreased.[ 121 ]

Along with the above‐discussed experimental studies, simulations were performed for xylene separation by MOFs. Jiang and co‐workers reported a molecular dynamics (MD) simulation study to examine liquid separation of xylenes with hexane as a mobile phase and MIL‐101 as a stationary phase.[ 128 ] As demonstrated in Figure 14 , the transport velocities of three xylenes isomers were predicted to rise as p‐xylene > m‐xylene > o‐xylene, consistent with experiment. The interactions of p‐, m‐, and o‐xylenes with MIL‐101 (∆E framework) increased from −24.6, −27.0 to −29.0 kJ mol−1, while the interactions with hexane (∆E solvent) decreased from −37.3, −36.9 to −36.5 kJ mol−1. Therefore, p‐xylene interacted the most weakly with MIL‐101 but the most strongly with hexane, thus exhibiting the fastest transport velocity. The ΔΔE ( = ∆E solvent − ∆E framework) were estimated to be −12.7, −9.9, and −7.5 kJ mol−1 for p‐, m‐, and o‐xylenes, respectively, with the same decreasing trend as the transport velocities. The difference in ΔΔE among the three xylenes was greater than in either ΔE framework or ΔE solvent, suggesting a cooperative contribution of solute‐framework and solute‐solvent interactions to the observed separation. In accord with energetic analysis, structural analysis based on radial distribution functions further indicated the closest contact of o‐xylene to MIL‐101.[ 128 ]

Figure 14.

a) Transport velocities of xylene isomers versus external force. b) Interaction energies of xylene isomers with MIL‐101 and hexane, respectively. Reproduced with permission.[ 128 ] Copyright 2013, American Chemical Society.

Based on grand‐canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) simulations, Torres‐Knoop et al. examined 14 MOFs, as well as 12 zeolites, for the adsorption and separation of xylene isomers, highlighted the crucial role of channel dimension in governing separation. With commensurate stacking, MAF‐X8 was identified as a promising candidate for p‐xylene adsorption.[ 129 ] Agrawal et al. combined experiment and computation to study the adsorption and separation of xylene isomers by flexible MIL‐53 with a focus on the effects of different metals (Al, Cr and Ga). Compared with MIL‐53(Cr) and MIL‐53(Ga), MIL‐53(Al) was found to have the highest gravimetric saturation capacity and the lowest transition pressure for o‐xylene. In accord with this trend, high o‐xylene selectivity was obtained with MIL‐53(Al) being the most selective and the simulation showed good overall agreement with experiment.[ 130 ] From computational screening of ≈ 2500 MOFs, Sholl and co‐workers predicted two MOFs (MOF‐48 and MIL‐140B) with comparable performance to zeolite BaX, which is currently used in industrial p‐xylene enrichment from C8 aromatics mixture; then they synthesized the top performing MOFs and evaluated through breakthrough adsorption experiment.[ 131 ]

Huang and co‐workers reported the selective separation of p‐xylene from its isomers by pervaporation using a highly selective and stable MIL‐160 membrane. As illustrated in Figure 15a, the suitable pore size (0.5–0.6 nm) of MIL‐160 was expected to allow p‐xylene to pass through, while excluding bulkier o‐/m‐xylenes. However, it was found that both m‐xylene and o‐xylene could enter into the channels of MIL‐160. This was attributed to the effect of framework flexibility and further supported by molecular simulation. As illustrated by the simulation snapshot in Figure 15b, p‐xylene was shown to be predominantly adsorbed over o‐xylene in MIL‐160 due to its stronger interaction with MIL‐160 than o‐xylene. As a result of both higher adsorption and diffusion selectivities of p‐xylene over o‐xylene, p‐xylene was observed to possess a higher permeability than o‐xylene through the membrane. This study reveals MIL‐160 membrane as a promising candidate for the separation of xylene isomers by pervaporation. [ 132 ]

Figure 15.

a) Schematic representation of the separation of p‐xylene from o‐xylene and m‐xylene through MIL‐160 membrane. b) Simulation snapshot of p‐xylene (green) and o‐xylene (yellow) adsorbed in MIL‐160 at 75 °C and 10 kPa, showing an enrichment of p‐xylene over o‐xylene due to the stronger interaction between p‐xylene and MIL‐160. Reproduced with permission.[ 132 ] Copyright 2018, Wiley‐VCH.

Predominant studies listed in Table 2 for aromatics separation were focused on selective adsorption of isomeric aromatics. These studies indicate that the underlying mechanisms for aromatics separation are a complex interplay of many factors including size‐, shape‐ and topology‐based exclusion, entropic and packing effect; meanwhile, aromatics‐MOF interaction like π‐complexation, enthalpic effect, solvent polarity and hydrophobicity all come into play for separation. Engaging such a large variation of strategies to tune separation performance is not possible for traditional porous materials. Moreover, the unique structural flexibility of MOFs due to breathing or gate‐opening (e.g., MIL‐53) provides additional tunability for separation. The implementation of MOF‐based membranes in aromatics separation is in its incipiency, primarily by pervaporation.[ 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 , 120 ]

3. Environmental Sector

3.1. Water Treatment

Water scarcity has been a global concern and how to efficiently supply fresh water is a topical issue. Meanwhile, substantial amount of contaminants such as metal ions and organic compounds (e.g., aromatics, dyes, and pharmaceuticals) have been introduced into water due to increasing world population and economic development. It is indispensable to remove these contaminants from water, thus minimizing health and environmental risks. A handful of techniques have been proposed for water treatment such as ion exchange, adsorption and membrane filtration using inorganic and polymeric materials.[ 133 ] However, these materials usually possess small pores, thus leading to slow kinetics and low capacity.

MOFs have been examined to remove ions and organics as summarized in Table 3 . Mi et al. reported a zinc ferrocenyl sulfonate MOF, Zn(4,4’‐bpy)2‐(FcphSO3)2 as a molecular aspirator for the removal of toxic metal ions (Pb2+, Cd2+, Cu2+, Mn2+, Co2+, Ni2+, and Zn2+). They observed that a powdered sample could remove metal ions mainly by sorption; however, ion exchange was observed in a single crystalline sample. Figure 16 plots the percentages of adsorbed metal ions (columns a–c) and exchanged Zn2+ ions (columns d–f) from solutions at different concentrations of metal ions. With increasing ion concentration, the percentage of exchanged Zn2+ ions and the quantity of adsorbed metal ions were found to increase. Thus, metal ion sorption occurred mainly in a dilute solution, whereas both ion sorption and exchange were present in a concentrated solution. This study implies the complex mechanisms involved in the removal of metal ions by a MOF.[ 135 ]

Table 3.

Removal of ions and organics from water

| Species | MOF | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Mn2+, Zn2+, Pb2+ | Cd(bpp)2‐(O3SFcSO3), Cd(bpy)2‐(O3SFcSO3) | [ 134 ] |

| Mn2+, Zn2+, Pb2+, Cd2+ | Zn(4,4’‐bpy)2‐(FcphSO3)2 | [ 135 ] |

| Li+‐Cs+, Mg2+‐Ba2+, Mn2+‐Zn2+, Fe3+ | NaLa(H4L) | [ 136 ] |

| Cd2+, Hg2+ | PCN‐100, PCN‐101 | [ 137 ] |

| Cd2+ | Cu3(BTC)2‐SO3H | [ 138 ] |

| CH3Hg+, Hg2+ | BioMOF | [ 139 ] |

| Hg2+ | Thiol‐functionalized HKUST‐1 | [ 140 ] |

| As5+ | Fe‐BTC | [ 141 ] |

| Hg2+, Bi3+, Zn2+, Pb2+, Cd2+ | UiO‐66 | [ 142 ] |

| Hg2+ | Thiol‐laced UiO‐66 | [ 143 ] |

| Hg2+, Pb2+ | Fe‐BTC/PDA composite | [ 144 ] |

| Cu2+, Ni2+ | UiO‐66(Zr)‐2COOH | [ 145 ] |

| Cu2+, Co2+ | [Zn(trz)(H2betc)0.5]·DMF | [ 146 ] |

| Pb2+ | MOF‐5, UiO‐66, MIL‐101(Cr), MIL‐53(Fe), ZIF‐8, MOF‐5, IRMOF‐3 | [ 147 ] |

| Pb2+ | DUT‐67 | [ 148 ] |

| Cs+, Sr2+ | MIL‐101‐SO3H | [ 149 ] |

| Ba2+ | MIL‐101‐SO3H, MOF‐808‐SO4 | [ 150 ] |

| Cu2+ | [(Zn3L3(H2O)6][(Na)(NO3)] | [ 151 ] |

| UO2 2+, UO2(OH)+, UO2(OH)2+ | HKUST‐1 | [ 152 ] |

| UO2 2+ | UiO‐68‐NH2, UiO‐68‐P(O)(OEt)2, UiO‐68‐P(O)(OH)2 | [ 153 ] |

| UO2 2+ | MOF‐76 | [ 154 ] |

| UO2 2+ | Amine‐derived UiO‐66 | [ 155 ] |

| UO2 2+ | Zn‐MOF | [ 156 ] |

| UO2 2+ | MISS‐PAF‐1 | [ 157 ] |

| Cs+ | [(CH3)2NH2]4[(UO2)4(TBAPy)3]·18DMF·17H2O, [(CH3)2NH2]4[(UO2)4(TBAPy)3]·22DMF·37H2O | [ 158 ] |

| As5+, ethylene blue | MFC‐N‐100 | [ 159 ] |

| Cd2+ | CTF‐1 | [ 160 ] |

| As3+ | MIL‐100(Fe) | [ 161 ] |

| Pb2+ | Fe3O4/MIL‐96(Al) | [ 162 ] |

| Co2+, Cd2+, Cu2+, Cr3+, Fe2+, and Pb2+ | TMU‐6,TMU‐21, TMU‐23, TMU‐24 | [ 163 ] |

| SO4 2− | Urea‐functionalized MOF | [ 164 ] |

| F− | MIL‐53(Al, Fe, Cr), MIL‐68, CAU‐1, CAU‐6, UiO‐66(Hf, Zr), ZIF‐7, ‐8, ‐9 | [ 165 ] |

| F− | MIL‐96 | [ 166 ] |

| I− | MOF@cellulose aerogels | [ 167 ] |

| Cr2O7 2− | FIR‐53, FIR‐54 | [ 168 ] |

| Cr2O7 2− | ZJU‐101 | [ 169 ] |

| Cr2O7 2− , MnO4 − | Cationic Ni‐MOF | [ 170 ] |

| HCrO4 − , CrO4 2− | TMU‐30 | [ 171 ] |

| MnO4 −, ReO4 − | SLUG‐21, SLUG‐22 | [ 172 ] |

| H2ASO4 −, HASO4 2− | UiO‐66 | [ 173 ] |

| ASO4 3−, ASO3 3− | UiO‐66 analogues | [ 174 ] |

| ASO4 3− | NH2‐MIL‐88(Fe) | [ 175 ] |

| ASO4 3− | ZIF‐8/sodium alginate | [ 176 ] |

| SeO4 2−, SeO3 2− | NU‐1000, UiO‐66, UiO‐67 | [ 177 ] |

| Cr2O7 2− | MOF+ | [ 178 ] |

| NaCl | UiO‐66 membrane | [ 179 ] |

| NaCl | MIL‐53/PVA membranes | [ 180 ] |

| Benzene | MIL‐101 | [ 181 ] |

| Methyl orange, methylene blue | MIL‐53, MIL‐101, MOF‐235 | [ 182 , 183 ] |

| HAsO4 2−, methylene blue, rhodamine B, coomassie brilliant blue G‐250 | MIL‐100(Fe), MIL‐100(Al) | [ 184 ] |

| Methanol, ethanol, acetone, tetrahydrofuran | Zn2(IDC)4(OH)2(Hprz)2 | [ 185 ] |

| Acetonitrile | Basolite F300, Z1200, C300, A100 | [ 186 ] |

| Xylenol orange | MIL‐101 | [ 187 ] |

| Phenol, p‐cresol, sugar | MIL‐53 | [ 188 ] |

| Nitrobenzene | MIL‐53 | [ 189 ] |

| Malachite green | MIL‐53, MIL‐100 | [ 190 ] |

| Congo red, brilliant black, direct red, etc. | MBioF | [ 191 ] |

| Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons | Fe‐BTC | [ 192 ] |

| Saturated hydrocarbons | PCPF‐1 | [ 193 ] |

| MnO4 −, dyes, methyl blue, methyl orange | 3D‐ionic COFs | [ 194 ] |

| Furosemide, sulfasalazine | HKUST‐1, MIL‐100 | [ 195 ] |

| Naproxen, clofibric acid | MIL‐100, MIL‐101 | [ 196 ] |

| Saccharin, acesulfame, cyclamate | MAF‐6 | [ 197 ] |

| Rhodamine B | Carbonized CoMOF | [ 198 ] |

| Atrazine | ZIF‐8, UiO‐66, and UiO‐67 | [ 199 ] |

| Methylene blue | JLUE‐COP‐1 and JLUE‐COP‐2 | [ 200 ] |

| Methylene blue | MIL‐100(Fe)‐KG, ZIF‐8‐KG, CuBTC‐KG | [ 201 ] |

| Methylene blue | PVBA‐UiO‐66 | [ 202 ] |

| Oil (n‐hexane, gasoline, soybean oil, diesel, toluene) | F‐ZIF‐90@PDA@sponge | [ 203 ] |

| Dye | ZIF‐8 on PVDF hollow fibers | [ 204 ] |

| NaCl | ZIF‐8 membrane | [ 205 ] (sim.) |

| NaCl | ZIF‐25, ‐71, ‐93, ‐96, and ‐97 | [ 206 ] (sim.) |

| NaCl | ZIF‐8, ‐93, ‐95, ‐97, and ‐100 | [ 207 ] (sim.) |

| NaCl | ZIF‐25 | [ 208 ] (sim.) |

| NaCl | ZIF‐8 | [ 209 ] (sim.) |

| Pb2+ | Na‐rho‐ZMOF | [ 210 ] (sim.) |

| Dimethyl sulfoxide | Zn4O(bdc)(bpz)2, Zn(bdc)(ted)0.5, ZIF‐71 | [ 211 ] (sim.) |

| Dimethyl sulfoxide | UiO‐66, UiO‐66‐F4, ‐(CH3)2, ‐(COOH)2, ‐(CF3)2, and ‐naphthyl | [ 212 ] (sim.) |

| Aniline and phenol | MIL‐53(Al) | [ 213 ] (exp./sim.) |

| Pd2+, Pt4+, Au3+ | Zr‐MOFs, UiO‐66‐NH2 | [ 214 ] (exp./DFT) |

| NaCl | ZIF‐7, ‐8, and ‐90 on α‐Al2O3 | [ 215 ] (exp./sim.) |

| NaCl, MgCl2, FeCl3, Na2SO4, MgSO4 | COF membranes | [ 216 ] (exp./sim.) |

Figure 16.

Percentages of adsorbed metal ions and exchanged Zn2+ ions by Zn(4,4’‐bpy)2‐(FcphSO3)2 from the solutions at different concentrations of Mn2+, Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Cd2+, and Pb2+. The red, orange, and yellow columns represent the percentages of exchanged Zn2+ ions from solutions at 10, 100, and 1000 µg mL−1, respectively, whereas the brown, blue, and cyan columns represent the percentages of adsorbed metal ions from solution at 10, 100, and 1000 µg mL−1, respectively. Reproduced with permission.[ 135 ] Copyright 2008, Wiley‐VCH.

By the coordination bonding of Cu2+ with –SH group in dithioglycol, Ke et al. functionalized HKUST‐1 and found it to possess remarkably high adsorption affinity and capacity for Hg2+, while the unfunctionalized counterpart showed no adsorption of Hg2+.[ 140 ] Through a simple solvothermal method, Zhu et al. synthesized Fe‐BTC and examined the kinetics and thermodynamics of As5+ adsorption. Fe‐BTC was found to possess high As5+ adsorption capacity, about 6.5 times that of 50 nm Fe2O3 nanoparticles.[ 141 ] Lin and co‐workers prepared three highly porous and stable MOFs with UiO‐68 network topology using amino‐TPDC or TPDC bridging ligands. These phosphorylurea‐derived MOFs were found to be efficient in sorbing uranyl ions from water and artificial seawater. The highest saturation capacity was up to 217 mg g−1, at least fourfold larger than that in amidoxime polymers. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations in both gas phase and water revealed that two phosphorylurea groups could bind favorably to one uranyl ion.[ 153 ] To provide systematic insight into the effects of functional groups on adsorption of metal ions, Esrafili et al. synthesized four isoreticular Zn‐based MOFs (TMU‐6, ‐21, ‐23, and ‐24 shown in Figure 17 ) by a mechanochemical method. Compared with imine and naphthyl groups, amide and phenyl groups in these MOFs were found to have greater adsorption of metal ions. Amide‐containing TMU‐23 showed efficient extraction and removal of metal ions (Co2+, Cd2+, Cu2+, Cr3+, Fe2+, and Pb2+). In addition, DFT calculations were performed on possible coordination between ion and functional group in each MOF.[ 163 ]

Figure 17.

Pores with imine and amide groups in a) TMU‐6, b) TMU‐21, c) TMU‐23, and d) TMU‐24. Reproduced with permission.[ 163 ] Copyright 2018, Royal Society of Chemistry.

Under microwave irradiation, Jhung et al. synthesized MIL‐101(Cr) and examined benzene adsorption from aqueous solutions. Compared with activated carbon, MIL‐101 was observed to adsorb a higher amount of benzene. Additionally, the rate of benzene adsorption was faster due to the giant pores in MIL‐101.[ 181 ] They further reported the removal of harmful dyes, anionic methyl orange (MO) and cationic methylene blue (MB) from aqueous solutions using MIL‐53, MIL‐101, and MOF‐235. The removal was revealed to be a spontaneous endothermic process and driven by entropy effect rather than enthalpy change.[ 182 , 183 ] Chen et al. reported kinetic and thermodynamic studies on the adsorption of xylenol orange (XO) into MIL‐101 from wastewater. A pseudo second‐order kinetic model was found to well describe experimental data. Thermodynamic parameters including free energy, enthalpy and entropy of adsorption were obtained and all were in favor of XO adsorption. Interestingly, the adsorbed amount was found to decrease with increasing pH value of XO solution and approach zero at pH = 12. As illustrated in Figure 18 , the adsorption mechanism was attributed to charge interaction between XO and MIL‐101. Compared with active carbon and MCM‐41, MIL‐101 was shown better adsorption capacity over a wider concentration range, suggesting a great prospect for dye removal.[ 187 ]

Figure 18.

Adsorption of xylenol organe (represented by R‐SO3 −) in MIL‐101. Reproduced with permission.[ 187 ] Copyright 2012, Elsevier.

Hybrid gels in a capillary using Fe‐BTC were fabricated by Hu et al. and coupled with HPLC for the online enrichment of trace polycyclic aromatics from water and of amphetamines drugs from urine. As attributed to π–π interactions between the Fe‐BTC framework and aromatic rings of analytes, excellent enrichment performance was observed.[ 192 ] Via homo‐coupling reaction of a custom‐designed ligand, Ma and co‐workers synthesized a highly porous covalent porphyrin framework (PCPF‐1) with a strong hydrophobicity. PCPF‐1 was shown high adsorptive capacities for both vapor and liquid saturated C5‐C8 hydrocarbons as well as liquid gasoline towards the cleanup of oil spill in water.[ 193 ]

Pharmaceutical compounds have turned out to be an emerging class of environmental contaminants in water, thus are required to be removed. Cychosz and Matzger examined water stability of seven microporous MOFs using power X‐ray diffraction, then tested HKUST‐1 and MIL‐100 for the adsorption of furosemide and sulfasalazine. Large adsorption capacities were obtained in MIL‐100, implying the potential application of MIL‐100 for water purification.[ 195 ] The adsorptive removal of two typical pharmaceuticals and personal care products (naproxen and clofibric acid) was also investigated by Jhung and co‐workers in MIL‐100 and MIL‐101, as well as in activated carbon. The adsorption rate and capacity were found to decrease in the order of MIL‐101 > MIL‐100 > activated carbon, largely depending on the pore size and volume of adsorbent.[ 196 ]

It is worthwhile to note that Jiang's group reported several simulation studies on water treatment by MOFs, including water desalination, removal of toxic Pb2+ and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) from water. Specifically, ZIF‐8 membrane was demonstrated to act as a reverse osmosis (RO) membrane to seawater desalination, as shown in Figure 19 . Under a sufficiently large external pressure, water was observed to permeate through the ZIF‐8 membrane, whereas Na+ and Cl− ions could not due to the sieving of small apertures in ZIF‐8. Water flux was found to scale linearly with the external pressure. Because of the surface interaction and geometrical confinement, water in the membrane was predicted to experience less hydrogen‐bonding and longer life time compared with bulk water.[ 205 ] Subsequently, water desalination was simulated through five ZIF membranes (ZIF‐25, ‐71, ‐93, ‐96, and ‐97) with identical topology but different functional groups. With larger apertures, ZIF‐25, ‐71, and ‐96 were shown to possess a much higher water flux than ZIF‐93 and ‐97. However, the polarity of functional group rather than aperture size was revealed to determine water flux through ZIF‐25, ‐71, and ‐96. Among the three, ZIF‐25 with hydrophobic –CH3 groups showed the highest flux despite the smallest aperture size. Water molecules were observed to go through fast flushing motion in ZIF‐25, but frequent jumping in ZIF‐96 and particularly in ZIF‐97.[ 206 ] Furthermore, seawater pervaporation in series of ZIFs (ZIF‐8, ‐93, ‐95, ‐97, and ‐100) was simulated. ZIF‐100 with the largest aperture was predicted to possess the highest water permeability of 5 × 10−4 kg m m−2 h−1 bar−1, which is higher than commercial RO membranes, zeolite and graphene oxide membranes. For ZIF‐8, ‐93, ‐95, and ‐97 with similar aperture size, water flux was revealed to depend on framework hydrophobicity. A to‐and‐fro motion was seen for water in ZIF‐100, such information on dynamic properties of water is useful to design new membranes for water desalination.[ 207 ]

Figure 19.

a) Water desalination through a ZIF‐8 membrane. Two chambers (aqueous solution with 0.5 M NaCl on the left and pure water bath on the right) were separated by a ZIF‐8 membrane. ZIF‐8, yellow; Na+, blue; Cl−, gray; H of H2O, white; O of H2O, magenta (left chamber), and green (right chamber). b) Number of net transferred water molecules from NaCl solution to pure water bath. Reproduced with permission.[ 205 ] Copyright 2011, American Institute of Physics.

To remove toxic ions from water, Nalaparaju and Jiang simulated the exchange of Pb2+ ions in aqueous solution with Na+ ions in Na‐rho‐ZMOF. Figure 20 shows the ion‐exchange process at different durations. Initially, Pb2+ and Cl− ions were in the solution and Na+ ions in rho‐ZMOF. Once starting simulation, Pb2+ ions were observed to rapidly move into the framework, while Na+ ions moving out. At 0.2 ns, a large number of Pb2+ ions moved into rho‐ZMOF, particularly near the solution/rho‐ZMOF interface. Meanwhile, Na+ ions moved out and stayed in the solution. Once exchanged, Pb2+ ions were found to prefer staying in the framework without moving back to solution. At 2 ns, all the Pb2+ ions were exchanged and resided in the framework. By umbrella sampling, the potentials of mean force (PMFs) were estimated for ions moving from the solution into rho‐ZMOF. The PMF for Pb2+ was predicted about −10 k B T and more favorable than −5 k B T for Na+. From the residence‐time distributions and mean‐squared displacements, all the exchanged Pb2+ ions were shown to constantly stay in rho‐ZMOF without exchanging with other ions in the solution. The exchanged Pb2+ ions in rho‐ZMOF were identified to locate at the 8‐, 6‐, and 4‐member rings with different dynamics.[ 210 ] This simulation study provides microscopic insight into ion exchange between aqueous solution and rho‐ZMOF. However, it should be noted that the solvent (water) was represented by a dielectric continuum. While offering several advantages, the implicit solvent approach lacks atomistic resolution particularly in dynamics. To more precisely describe the dynamics, solvent molecules should be explicitly taken into account, but simulation will be substantially longer.

Figure 20.

Removal of Pb2+ by ion exchange in Na‐rho‐ZMOF at 0, 0.2, and 2 ns, respectively. Pb2+: orange; Cl−: green; Na+: blue. Reproduced with permission.[ 210 ] Copyright 2012, American Chemical Society.

Nalaparaju and Jiang also conducted a simulation study to examine DMSO recovery from aqueous solution by Zn4O(bdc)(bpz)2, Zn(bdc)(ted)0.5, and ZIF‐71. Due to the hydrophobic nature, the three MOFs showed highly selective adsorption of DMSO from DMSO/H2O mixtures. The adsorption selectivity of DMSO over H2O was increased initially with increasing the composition of DMSO (X DMSO), then decreased within the range of X DMSO considered in the study. The initial increase was attributed to the favorable interaction of DMSO with multiple adsorption sites in the framework. However, the interaction could weaken when most adsorption sites were occupied and furthermore smaller H2O molecules were more easily fill into the framework; consequently, a decrease in selectivity was seen at high X DMSO. The highest selectivity was predicted up to 1700 in ZIF‐71; nonetheless, the recovery capacity of DMSO in ZIF‐71 was substantially smaller than in Zn4O(bdc)(bpz)2 and Zn(bdc)(ted)0.5. Therefore, Zn4O(bdc)(bpz)2 and Zn(bdc)(ted)0.5 might be practically better among the three MOFs for DMSO recovery.[ 211 ]

By combining experiment and simulation, the adsorption of aniline/phenol from aqueous solutions by MIL‐53(Al) was investigated by Zhong and co‐workers. Besides framework flexibility, coadsorbed water molecules were also found to affect the adsorption of both aniline and phenol. Interestingly, more water molecules were trapped in MIL‐53(Al) accompanying with phenol adsorption (0.64 water molecules per unit cell versus 0.11 in the case of aniline adsorption). This was attributed to stronger hydrogen bonding of phenol with water than of aniline. This study suggests such a flexible material might be useful for separating aniline/phenol from their mixed aqueous solutions.[ 213 ] Yun and co‐workers explored the adsorption of PdCl4 2−, PtCl6 2−, and AuCl4 − from strongly acidic solutions by UiO‐66 and UiO‐66‐NH2. Experimentally, both MOFs showed rapid uptake rate and high adsorption capacity. As shown in Figure 21 , their DFT calculations indicated the anions binding onto two Zr sites with energies higher than those binding onto one Zr site. The inner‐sphere complexation between anions and incompletely coordinated Zr sites was revealed to be the key mechanism contributing to the adsorption. In UiO‐66‐NH2, additional electrostatic attraction between the protonated amine group (–NH3 +) and anions was observed along with the partial reduction of bound anions.[ 214 ] Through post‐modification, Huang and co‐workers constricted the pore aperture of a covalent organic framework (COF) membrane, IISERP‐COOH‐COF1. With superior stability, the membrane exhibited high water permeance above 0.5 L m−2 h−1 bar−1 and superior ion rejection for various salts (82.9% NaCl, 90.6% MgCl2, 99.6% FeCl3, 96.3% Na2SO4, and 97.2% MgSO4). The experimental observation was supported by molecular simulation.[ 216 ]

Figure 21.

Binding energies of anions onto a) one Zr site and b) two Zr sites. c) Binding modes and reduction pathways of anions in UiO‐66‐NH2. Reproduced with permission.[ 214 ] Copyright 2017, Royal Society of Chemistry.

The development of water stable MOFs, particularly MIL, UiO and ZIF families, has provided plenty of opportunities to use MOFs for water treatment. As discussed above, with diversified pores, topologies and structures, MOFs can adsorb a wide variety of molecules ranging from small ions to large organics from water or aqueous solutions. For cation removal, MOFs possess the intrinsic mechanisms from both organic and inorganic counterparts, such as chelation by organic functional groups and ion exchange with framework or nonframework ions. MOFs can also be used for selective anion removal by ion exchange, which is not easily achievable in many other porous materials.[ 164 ] For organics removal, pore volume, surface area, π–π and electrostatic interactions are the main governing factors. Compared with zeolites and activated carbons, MOFs exhibit higher capacity and efficiency for the removal of large organics. Furthermore, MOFs have been tested for membrane‐based water treatment processes such as ultrafiltration, forward osmosis, reverse osmosis and nanofiltration. Computational studies are instrumental to provide mechanistic insights into the fundamental mechanisms of adsorption, ion exchange and membrane separation for water treatment.

3.2. Solvent Recovery

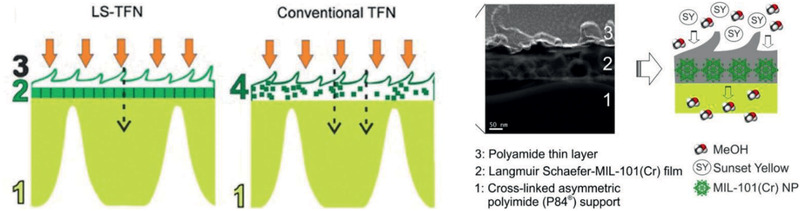

In the chemical and pharmaceutical industries, organic solvents are widely used as raw materials, reaction media and cleaning agents. A large amount of solvents after use are simply disposed by incineration. From environmental and economic aspects, it is beneficial to recover solvents. Adsorption is not well‐suited for large‐scale solvent recovery due to high energy consumption, low efficiency and difficulty in recycling. Instead, membrane separation is more effective with low energy requirement, high selectivity, flexibility in design and environmental friendliness. Organic solvent nanofiltration (OSN) is a promising membrane‐based, energy efficient technology for solvent recovery. Most of the current OSN membranes are polymer based. To attain superior‐performance OSN, a narrow pore size distribution is important for the discrimination of molecules of similar size, which however is difficult to be produced in polymer membranes. In this aspect, microporous crystalline materials are of immense potential to be developed into OSN membranes. Recently, different types of MOF‐based OSN membranes have been produced, namely, mixed‐matrix membranes (MMMs), thin‐film nanocomposite (TFN) membranes, and thin‐film composite (TFC) membranes. Examples of these membrane used for solvent recovery are listed in Table 4 .

Table 4.

Solvent Recovery

| Solution | MOF | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| MMM | ||

| Rose bengal in isopropanol | Cu3(BTC)2, MIL‐47, MIL‐53, ZIF‐8/PDMS | [ 217 ] |

| Polystyrene oligomer, methyl styrene dimer in acetone | ISG HKUST‐1/PI P84 | [ 218 , 219 ] |

| Brilliant blue G in ethanol | MIL‐53(Al)/PMIA | [ 220 ] |

| Reactive red 120, methyl blue, reactive orange 16, methyl red in methanol | Cu‐BTC/PPSU | [ 221 ] |

| Reactive orange 16 in methanol | Cu‐BTC/PPSU | [ 222 ] |

| Rose bengal, methylene red in methanol | ZIF‐8@resin microspheres/PPSU | [ 223 ] |

| Congo red in ethanol and IPA | Carbonized ZIF‐8/PI | [ 224 ] |

| TFN | ||

| Polystyrene oligomer in methanol and tetrahydrofuran | NH2‐MIL‐53(Al), MIL‐53(Al), ZIF‐8, MIL‐101(Cr)/P84 | [ 225 ] |

| Acridine orange, sunset yellow, and Rose bengal in methanol | MIL‐101(Cr), MIL‐68(Al), ZIF‐11/P84 | [ 226 ] |

| Sunset yellow, acridine orange in methanol | MIL‐101(Cr) and ZIF‐11/P84 | [ 227 ] |

| Sunset yellow in methanol | ZIF‐8 and ZIF‐67/P84 | [ 228 ] |

| Methyl blue dye in methanol | ZIF‐8@GO composite/PEI | [ 229 ] |

| Rose bengal in various solvents | UiO‐66/PA | [ 230 ] |

| Tetracyline in methanol | DA‐UiO‐66‐NH2/PI | [ 231 ] |

| Rose bengal in ethanol | PAF‐1/PTMSP | [ 232 ] |

| Erythromycin and dyes in methanol, tetrahydrofuran, dimethyl formamide and butyl acetate | β‐CD@ZIF‐8/PA | [ 233 ] |

| Sunset yellow in methanol | ZIF‐8, ZIF‐93 and UiO‐66/P84 | [ 234 ] |

| Rose bengal, sunset yellow in methanol | LS‐MIL‐101(Cr)/P84 | [ 235 ] |

| Rhodamine B in ethanol and Rose bengal in DMF | SNW‐1 COF/PI | [ 236 ] |

| TFC | ||

| Rose bengal in ethanol or IPA | ZIF‐8/PES | [ 237 ] |

| Polystyrene oligomer, methyl styrene dimer in acetone | HKUST‐1/P84 | [ 238 ] |

| Brilliant blue R dye in IPA | Zn(BDC)/PAN | [ 239 ] |

| Rose bengal dye in methanol and isopropanol | MIL‐53(Al) and NH2‐MIL‐53(Al) | [ 240 ] |

| Dyes in acetonitrile, acetone, methanol, ethanol, isopropanol and dimethylformamide | CON films | [ 241 ] |

| Paracetamol in methanol, ethanol, acetonitrile, acetone and n‐hexane | ZIF‐25, ‐71, ‐96 | [ 242 ] (sim.) |

| FDA, PRM, MSD and NRD in acetonitrile, acetone, methanol, ethanol, IPA, MEK, and n‐hexane | COFs | [ 243 ] (sim.) |