Abstract

South Korea’s COVID-19 control strategy has been widely emulated. Korea’s ability to rapidly achieve disease control in early 2020 without a “Great Lockdown” despite its proximity to China and high population density make its achievement particularly intriguing. This paper helps explain Korea’s pre-existing capabilities which enabled the rapid and effective implementation of its COVID-19 control strategies. A systematic assessment across multiple domains demonstrates that South Korea’s advantages in controlling its epidemic are owed tremendously to legal and organizational reforms enacted after the MERS outbreak in 2015. Successful implementation of the Korean strategy required more than just a set of actions, measures and policies. It relied on a pre-existing legal framework, financing arrangements, governance and a workforce experienced in outbreak management.

Keywords: South Korea, COVID-19, MERS, Pre-exiting capabilities, Lessons learned, Preparedness, Response

1. Introduction

The impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been catastrophic, despite countries scrambling to respond with various measures to control the COVID-19 pandemic. The effectiveness of” the Great Lockdown” [1] depends on countries’ “pre-existing factors” such as prior institutional capabilities, social cohesion, and governance. There is no one-size-fits-all recipe.

Countries with early success in COVID-19 control have been lionized in the press [[2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7]]. South Korea’s COVID-19 control strategy emerged as a model to emulate, as it was one of the first countries that “flattened the curve” in 2020, despite its proximity to China and high population density [4,6,8]. For two weeks in late February, Korea had the highest number of confirmed COVID-19 cases outside China. The epidemic, however, was controlled rapidly. The elements of the South Korean approach – Test, Trace and Isolate, with the use of information and communication technology (ICT) and public-private partnership (PPP) – have gained broad consensus as a key for success [[4], [5], [6], [7],9]. However, there are limited assessments which are widely available on why such policies were developed and what enabled their successful implementation.

This paper documents the capabilities that enabled successful implementation of policies and strategies to control COVID-19 which has contributed in bending the first wave in South Korea. We conducted a systematic assessment of the capabilities that enabled rapid implementation of control polices, and then discuss lessons learned during the first wave of the epidemic in the country. Factors that allowed execution of the control strategy will remain relevant to recurrent outbreaks of COVID-19 and future infectious disease threats.

2. Epidemiological overview

South Korea was one of the first countries to be hit by COVID-19 due to its geographic proximity to China. The first case was confirmed on February 20th, and by February 29th, Korea had the highest number of confirmed cases outside China, reaching a peak of 909 new cases [10,11]. This spike originated from a cluster of a ‘Shincheonji’ [7] church, a secretive cult in the city of Daegu, a city of approximately 2.5 million people (hereafter referred to as ‘Daegu church’) [12]. However, in less than 2 weeks after the peak, the epidemic had already shifted to the stabilizing phase through an aggressive test-trace-isolate strategy [13,14]. Since mid-March, South Korea reduced its incidence rates by more than 90 % from its peak, achieving zero new domestic infections by May 6th [12,15]. There have been, though, a few setbacks along the way mostly in and around Seoul, including the second major outbreak in August again originated from a mega church [16]. However, Korea sustained some of the lowest cumulative incidence rates and case fatality rates among countries during the first wave and subsequent waves of COVID-19 without implementing draconian lockdown measures [4,5].

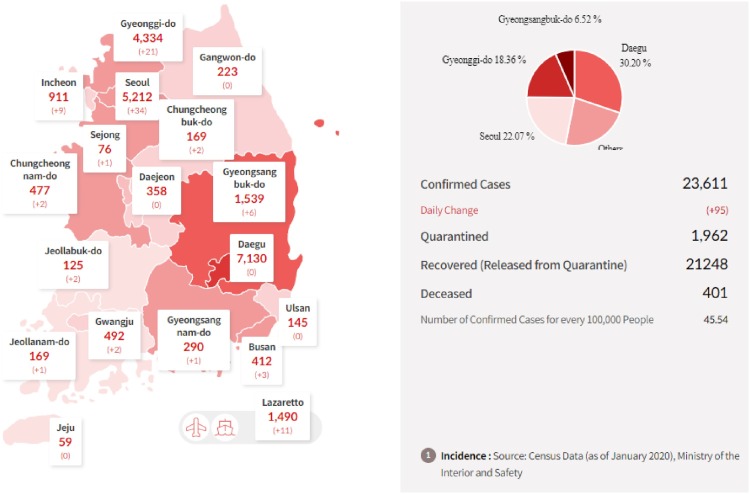

South Korea’s first big outbreak of 2020 occurred in a church in Daegu. With immediate control measures set from both the central and local government, the virus was contained within Daegu province which contributed to 80 % of total confirmed cases until June [5,17,18]. Subsequently, however, especially with the second outbreak in August, the epidemic spread to other provinces (Exhibit 1 ) [10,15,17,19]. Cumulative incidence rates among those in their 20 s is highest (69 per 100,000) as of late September, 2020 [15,20]. This contributes to the relatively young age-distribution among those with confirmed cases and relatively low overall case fatality rate overall (1.7 %).

Exhibit 1.

Cumulative Confirmed Cases by Provinces in Korea.

Source: Korea Ministry of Health and Welfare (as of September 27th 2020) [3], Census Data, Ministry of the Interior and Safety.

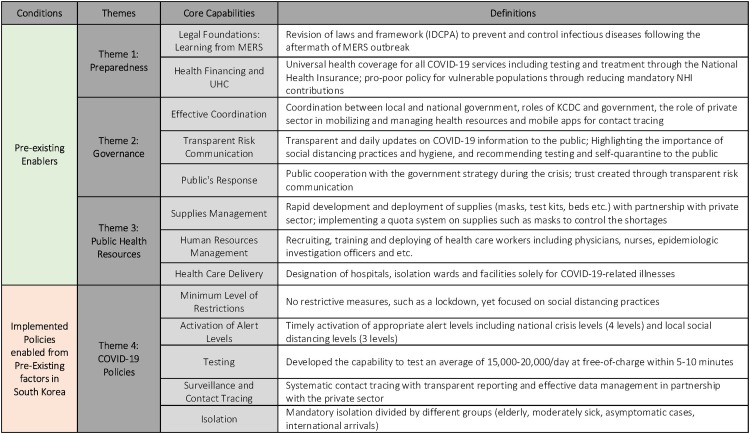

3. Materials and methods

We adapt and revise a framework from the WHO’s Joint External Evaluation (JEE) to systematically examine factors for South Korea’s capability to control COVID-19. The JEE framework assesses countries’ capacity to prevent, detect, and rapidly respond to public health risks. For this paper, we simplify JEE’s 49 indicators and 19 domains into four broad themes, including ‘Preparedness, ‘Governance’, ‘Public Health Resources’, and ‘COVID-19 Policies’, and thirteen core capabilities to better understand the pre-existing factors of health security in Korea (Exhibit 2 ). The first three themes are the “pre-existing enablers” that distinguish Korea from others, which allowed South Korea to implement effective and relevant COVID-19 policies (Theme 4).

Exhibit 2.

Core Capabilities Framework.

Source: Authors. Adapted from WHO’s JEE framework (2020).

An extensive literature review was performed to systematically assess Korea’s political economy, strategies and policies related to infectious diseases, and societal response to governmental measures. Literature databases included government reports and Korean government databases, scholarly articles and journals, international and local news articles. Scholarly and grey-literature databases include Google Scholar, PubMed, Korean search engines (Naver and Daum which are equivalent to Google), and websites (Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC), WHO, World Bank, Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) COVID-19 Resources, Our World in Data, Brookings institute, Health System Global, and South Korea’s Law and Regulation (Infectious Disease Control and Prevention Act (IDCPA)). News articles have played a significant role in the literature review process due to the revolving nature of the virus and polices.

Key search terms were informed by, but not limited to, WHO’s JEE framework and our revised ‘Core Capabilities Framework’. The search terms included “South Korea and COVID-19”, “MERS”, “preparedness”, “governance”, “public health resources”, “policies implemented”, “lessons learned”, “legal foundation after MERS”, “health financing and UHC”, “government coordination”, “government role”, “role of private sector”, “risk communication”, “public’s response”, “supplies management”, “innovative methods”, “healthcare workers mobilization”, “restrictions and lockdown”, “alert levels”, “social distancing levels”, “testing”, “surveillance and contact tracing”, and “isolation”. Both English and Korean articles have been considered to broaden the reach of information and data and to validate the claims. All articles and reports deemed relevant after title and/or abstract review have been considered for literature review. See Appendix 1 for full electronic search strategy.

The timeline of the systematic assessment extended from a few months prior to the inception of the MERS outbreak in South Korea (January 2015) to end of July 2020, to review all the literature available to date to thoroughly examine information on COVID-19. The 2015 start date offered perspective on how Korea’s approach was informed by MERS. The paper, however, has a limitation insofar that news and coverage of the epidemic is still evolving. Furthermore, because we relied on news articles, there may have been variations in the rigor used by journalists to support their claims with evidence. However, we cross-checked and triangulated news articles with Korean policy personnels to ensure the claims were accurate and reliable.

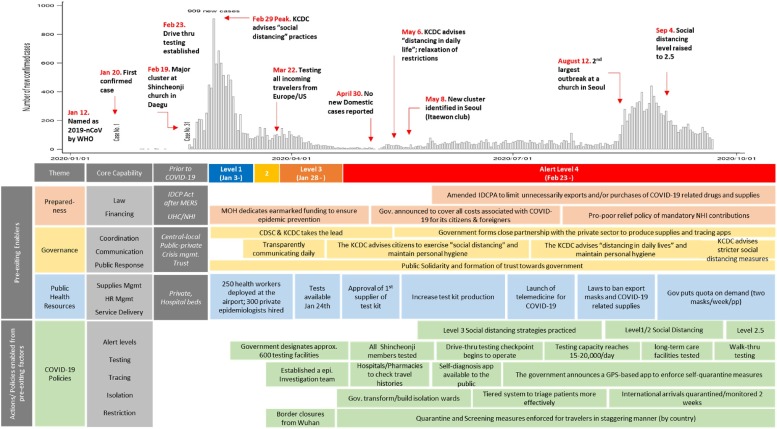

Below we discuss each of the twelve core capabilities in detail to better understand the pre-existing factors and actions taken to control the pandemic in Korea. Key capabilities of Korea’s COVID-19 response are presented in Exhibit 3 . Please see Appendix 2 for detailed timeline of Korea’s COVID-19 response and major events.

Exhibit 3.

Timeline of Policy and Actions taken to Control COVID-19.

Source: Authors’ synthesis using data from KCDC, news articles and journals.

4. Results: systematic review of core capabilities of South Korea

4.1. Theme 1: preparedness

4.1.1. Legal foundation: learning from MERS

Korea learned painful lessons during the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) crisis in 2015. South Korea had the largest outbreak outside the Arabian Peninsula [21]. The government’s inadequate response revealed significant drawbacks of its infectious disease control system and generated considerable criticism [7,22,23].

After the MERS outbreak, the country significantly reformed its laws and regulations to improve pandemic preparedness and response. The government established and revised the infectious disease prevention and control laws and frameworks. Twice in 2015, the Infectious Disease Control and Prevention Act (IDCPA) was amended [5], laying legal foundations for all dimensions of pandemic control. These amendments reinforced the leading authority of Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) and increased funding earmarked for pandemic preparedness. These funds allowed KCDC to recruit and retain healthcare workers and epidemic intelligence service (EIS) officers for outbreak management, infectious disease surveillance and response [7,24].

The IDCPA was further revised to enable extensive contact tracing [5]. It incorporated various investigation methods to allow KCDC and the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MoHW) to retrieve personal information such as GPS location and credit card transactions for accurate tracing [25]. In December 2015, the law was further revised, to allocate resources and mobilize public and private stakeholders and set clear roles and responsibilities, including financial, to control the outbreak. Public disclosure provisions were also included in the amendments for transparent communication during an outbreak.

Even during the COVID-19 crisis, the government further amended the Act to quickly react to the surging demand for supplies through limiting unnecessary exports and/or purchases of COVID-19 related drugs and supplies [5]. The amendment also enabled the government to distribute resources and mobilize various actors across the whole of society in the effort to fight against the spread of infectious disease [26]. By early March of 2020, the Mayor of Daegu city was able to secure more than 3000 beds with the amended Act [26]. These agile, rapid, real time amendments to the national authorizing legislation for disease control enabled urgent and decisive responses by a seasoned public health workforce, many of whom stayed in the workforce following the MERS outbreak.

4.1.2. Health financing and universal health coverage (UHC)

Under universal health coverage since 1989, all patients have access to all health services which are covered by the National Health Insurance (NHI) [27]. Although more than 90 % of health facilities are private, they are required to participate in the NHI system with the same contract conditions for both public and private providers set by NHI law. For communicable diseases, such as COVID-19, NHI covers the fees for all patients and providers. COVID-19 related copayments are exempted for citizens and foreigners under the NHI law. This funding is earmarked within the government’s budget, and its’ supportive public finance environment enabled to allocate budget funds to the response [28]. Testing is also performed free-of-charge in most cases. In addition, Korea implemented a pro-poor relief measure to provide a discount on the mandatory NHI contributions for people who are heavily affected from the outbreak. For instance, for the bottom 20 %, 50 % of the contribution is discounted, while a 30 % discount is applied for the 20–40 % income quintile [14]. The most COVID-19 affected area, Daegu city, received a 50 % discount for the bottom 50 % of the population [14]. During the quarantine, the government pays a cash support to compensate for the income loss. Korea’s COVID-19 experience highlights how UHC and pro-poor policies can be important foundations to cope with an epidemic and health security crisis.

4.2. Theme 2: governance

4.2.1. Effective government coordination

4.2.1.1. Coordination between the local and national government

During the MERS epidemic, coordination failed at various levels: within Korea’s central government, between the central and local governments, and between health authorities and private medical institutions [29]. It not only suffered from unclear sets of roles and responsibilities, but also led to conflicts between the national and local authorities.

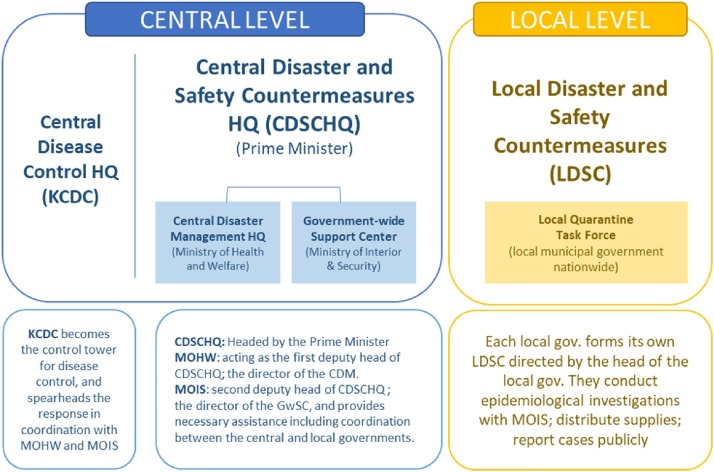

In the aftermath of MERS, strong national leadership and coordination were identified as critical, and the amendments of IDCPA in 2015 and 2017 included clear roles and responsibilities of central, state, and local governments as well as private institutions. In the response to COVID-19, the Central Disaster and Safety Countermeasures Headquarters (CDSCHQ), headed by the Prime Minister, directed the pandemic responses in coordination with the KCDC and local governments (Exhibit 4 ). It designated local governments to be responsible for disease control measures as well. KCDC also established the Office of Risk Communications to provide transparent and timely guidelines to the public.

Exhibit 4.

Response Systems of the Korean Government.

Source: Authors’ synthesis using data adapted from KCDC (2020).

South Korea, although decentralized with nine provinces, was able to implement a consistent national response to the pandemic. Grounded by the legal system, coordinated efforts between central and local government enabled Korea to effectively control COVID-19. Local authorities quickly acted and implemented local-level measures, e.g., closure of Daegu church-related facilities and meetings, but at the same time collaborated and followed the guidelines of KCDC and MoH, e.g., triage and treatment of COVID-19 patients as well as contact tracing and epidemiological investigation. Effective coordination between local and central government facilitated resource mobilization, data and reporting, and rapid testing of all 200,000 Daegu church members which allowed containment and control of the epidemic at the onset [12].

4.2.1.2. The role of private sector

The experience of MERS also prodded government under the President Moon Jae-in’s administration to build linkages enabling cooperation with the private sector in developing and deploying testing and treatment resources. Many private biotechnologies in Korea focused their research and development on infectious diseases after MERS, which also enabled effective public-private partnerships [7,30]. As a result, even before the first case in Korea, private test kit companies started looking into producing test kits in close partnership with the government, which allowed the production of 18,000–20,000 tests per day by the end of March. Protective masks were also produced by private companies and deployed to health care providers and citizens in just a few weeks after the first confirmed case. Contact tracing mobile apps were also produced by private companies and entrepreneurs with the public data available by the government [31]. Isolation wards (e.g., residential treatment centers for patients with mild symptoms) were also transformed from retreat centers owned by private corporations, which followed from policy also designated by the national government [3].

4.2.2. Transparent risk communication

Inadequate information disclosure was one of the main reasons for failures in the MERS epidemic control. MERS taught Korea how important effective crisis communication matters to counter misinformation. In 2015, the Korean government made amendments to the IDCPA, which mandated transparent and timely risk communications to the public [7,32,33]. Since the onset of the first case of COVID-19, the Minister of Health and Welfare and the Director of KCDC have been providing briefings everyday with detailed data and risks of COVID-19, and the importance of social distancing and hygiene though different platforms available, including a COVID-19 official website, TV and radio broadcasting, social media, and text messages [13,14,33,34]. The government made a conscious effort to create a sense of trust through timely and transparent crisis communication. In a recent opinion survey, 75.3 % mentioned that they trust the regular briefings by the government and 92.2 % trust KCDC [35]. These communications systems allowed citizens to not only form trust in the government, but also created a form of solidarity among the citizens.

4.2.3. Public’s response

The voluntary cooperation of the public — getting tested, wearing masks, self-isolating when symptoms arise, and social distancing in general – was essential in containing the virus [4,5,18,36]. The public’s consensus around taking precautionary measures and complying with the government was a result of the MERS outbreak [29,32]. The painful lessons learned from MERS and swift reforms made by the government solidified trust between the government and the public. The government provided transparent risk communication to the public which enabled citizens to follow those guidelines. Although the country experienced backlash due to privacy concerns after its extensive law revisions, public perception of the government’s response measures in a fully democratic country have generally been positive [37]. Without public cooperation, strategies to control COVID-19 would not have been possible. South Korea, thus, did not need to adopt more forceful measures as seen in China, and increasingly, in the US and Europe [1,33,38].

4.3. Theme 3: public health resources

4.3.1. Supplies management

The government adopted diverse measures to mobilize, secure and control the supplies. As the first early cases of COVID-19 were reported, the KCDC met with test kit producers and was already on a fast-track to prepare mass production of rapid diagnostic test kits. On the 4th of February, the test kit company received the government’s “emergency approval”, which was introduced after the MERS epidemic and allowed for a fast-track approval during outbreaks, and the next day test kits were distributed to health facilities across the country [7,9,13,14]. Test kit producers also received funds to rapidly develop test kits and to develop an epidemiological investigation support system under the National R&D Program. With this partnership, testing capacity reached 18,000–20,000 per day by mid-March [14].

The government imposed a limit of two masks a week per person, which were distributed on designated days of the week depending on birth year [14]. Real-time data on distributed masks is captured under the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) system of NHI and are publicly available through mobile applications and web services, addressing supply shortages and distribution inefficiency [13]. As the data are publicly available, it allows private sectors to develop various online and mobile services, enabling citizens to locate pharmacies with masks in stock. As domestic supply stabilized, the Korean government joined to reduce the global shortage of masks by sending out millions of masks to more than 22 countries [39].

4.3.2. Human resource management

The government was aggressive in recruiting health care professionals in order to support patient care and infection control in Daegu and Gyeongbuk Province. At the onset of the outbreak, the local government hired an additional 2400 health care workers in Daegu alone [7,14]. Hundreds of physicians and nurses also volunteered to participate in the COVID-19 response which helped meet the surging demand [40]. However, maintaining the supply of health workforce has been a challenge to meet surging demand, partly due to the current legal framework, which gives inadequate authority for the government to distribute and deploy health workers during a crisis. The government is currently looking at revising this legal framework [5,32,41].

Insufficient capacity to lead an epidemiological investigation and/or contract tracing was also a major pitfall during the MERS outbreak [7,22,29,32]. The revision of the IDCP Act after MERS enabled the government to recruit at least 30 epidemic intelligence service (EIS) officers within the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW). Right after the first confirmed case in the country, the act was again revised to increase epidemiological investigation capacity which enabled the government to hire a minimum of 100 EIS officers effective with MOHW’s budget [5]. In the beginning of March, this workforce of hundreds of EIS were already deployed for contact tracing with access to different types of data, including those from interviews, credit cards and mobile apps.

4.3.3. Health care delivery

Thanks to the flattening of the epidemiological curve, Korea did not suffer from a lack of hospital beds even during the apex of COVID-19, except for a short period of time in Daegu when there was a surge of patients [3,42]. The country has the second highest hospital bed capacity among OECD countries, which worked in its favor during the crisis. Nevertheless, the government implemented a strategy following the guidelines from the IDCPA to prepare for the worst. In early March, the government designated 69 public hospitals with approximately 7500 hospital beds (approx. 2.5 % of total hospital beds in Korea) solely for COVID-19 treatment, and most COVID-19 cases were treated in public facilities, while most private health facilities were hesitant in providing care and treatment for COVID-19 related illnesses [14]. Patients confirmed to have COVID-19 were classified by the severity of symptoms and treated accordingly. Moderate, mild, or asymptomatic patients stayed at community treatment centers operated by local governments [43]. Designation of treatment hospitals was a lesson learnt from the MERS outbreak when some health facilities were reluctant to accept MERS patients due to infections.

To secure a continuum of services for the non-COVID-19 related illnesses, “safety guaranteed healthy facilities” (SGHF), which separate patient paths for respiratory symptoms and other diseases, were also designated so that people could go freely without worrying about getting infected by the virus [5,14]. These designated SGHF account for approximately 20 % of total health facilities in the country and has helped to lessen the relative decrease of health care utilizations especially after outbreak, where Korea’s reduction of health utilization was far less compared to other OECD countries [14]. To continue certain health services, telemedicine was also implemented at the end of February to give over-the-phone medical consultation and prescriptions temporarily until the COVID-19 outbreak ends [14].

4.4. Theme 4: COVID-19 policies

4.4.1. Minimum level of restrictions

South Korea is one of the few countries that did not exercise restrictive measures, such as a large-scale lockdown, to contain COVID-19 successfully [4,19,42]. Instead, the government focused on aggressive testing, tracing, and isolating with strong leadership [4,13,42,44]. Reluctance to this lockdown is based on prior experience with MERS and its sharp economic downturn experienced with the lockdown. Unnecessary shutdown of schools and border restrictions across the country were executed due to excessive anxiety and fear that was spreading at that time [23].

For COVID-19, the government heavily emphasized social distancing and hygiene practices rather than a complete lockdown as we have seen in many of the developed countries [38,45]. Even in the midst of a pandemic, South Korea ran a nationwide general election to balance its obligations to public health and civil liberties. Citizens in self-isolation were allowed to cast their ballots after regular voting hours [46]. This minimum restriction has lessened the devastating economic impacts of COVID-19, and projected to be the least affected by COVID-19 of all OECD countries [38,42,45,47].

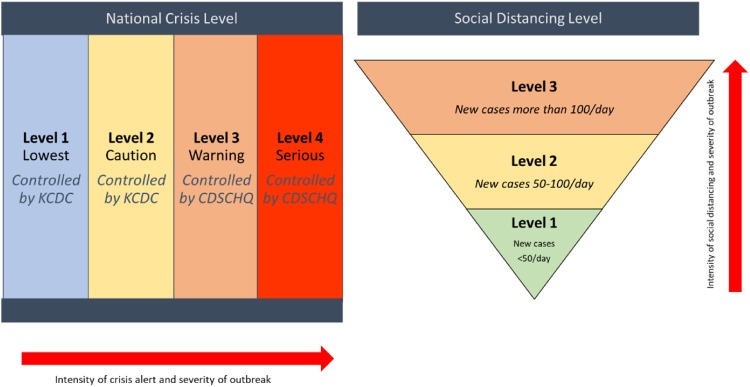

4.5. Timely activation of alert levels

4.5.1. National crisis levels

Korea’s management plan for infectious diseases establishes four crisis levels: attention, caution, alert, and severe, which is implemented in the national level (Exhibit 5 ). A key lesson learned from the MERS epidemic was the importance of timely activation of an appropriate level, as it allows the country to prepare for and respond to an outbreak at different stages. This activation enables government to take sweeping measures to contain COVID-19, from locking down the city to contact tracing, depending on the severity of the outbreak [13,14]. The management plan also strengthens coordination between the central government and local government to help contain the spread of the virus. Level 1 and 2 are managed by the KCDC while the higher levels are managed by the CDSCHQ [14].

Exhibit 5.

Alert Levels: National Crisis Level and Social Distancing Level.

Source: Authors’ synthesis using data adapted from government documents.

Crisis alert level 1 was raised on January 3rd, 2020, three days after COVID-19 was reported to WHO from China [14]. Under the activated systems, the government was able to start preventive measures, establishing preparedness and response plans, specifying the roles of relevant institutions, and activating potential personnel for epidemic control, including contract tracers. The highest level was raised on February 23rd, once the Daegu church outbreak was identified [14]. Elevating the alert to the maximum level allowed the government to coordinate with different line ministries and the private sector to take drastic measures such as restricting certain flights to and from South Korea, closing schools and limiting public transportation [14,19]. Border closings and draconian lockdowns were possible under the maximum alert level, but these measures were not implemented.

4.5.2. Social distancing levels

The Korean government implemented a three-tier social distancing scheme, which adjusts the intensity of infectious disease prevention guidelines depending on the severity of the outbreak (Exhibit 5). The level of social distancing is decided on the basis of the average number of daily new cases, percentage of new cases for which the origin of infection cannot be identified, impact on the economy, among other factors [14,48,49]. These measures can be undertaken by all levels of government including central, provincial, city and municipal governments, depending on its area’s severity of the outbreak [14]. The higher the level, the stricter the social distancing guidelines.

South Korea was mostly at Level 1 during the first half of 2020 when the virus was deemed to be manageable under the current medical system, with the daily rise of COVID-19 cases staying below 50 on average [12]. However, in early July 2020, there was an increase to Alert Level 2 in the western regions, including Gwangju and South Jeonla Province after seeing a sporadic cluster in that region [12]. Most recently, with the “second wave” in late August, the government tightened its social distancing rules by raising its social distancing level to 2.5 in the Greater Seoul area [49].

Government’s well-planned guidelines and its proactive measures played a significant role in achieving good social distancing and hygiene practices by the public. The government educated the public about the emerging virus and good prevention practices, which fostered an environment for citizens to know and follow the guidance provided from their public health authorities.

4.6. Rapid testing

South Korea and the United States both reported their first confirmed cases on January 20th [12,50]. One month later, Korea had the highest testing rates, while the US was ranking near the bottom [12,51]. This difference highlights Korea’s agility to reallocate productive capability and health workers. There was rapid scale up of domestically produced test-kits in the private sector and the construction of innovative and high-throughput screening clinics to ensure their immediate use [9,40]. This was also learned from MERS, where a lack of testing capabilities contributed to the spread of the outbreak. Prior to the first case confirmed in Korea, KCDC received viral specimens from China to develop test kits [3,13,14], and the government started producing diagnostic tools in partnership with private sectors.

The country built approximately 600 testing centers in March as soon as the first national alert was raised [7,19]. Innovative approaches were used to conduct tests at scale while minimizing the risk of transmission. Drive-thru testing was used early on, which takes less than 10 min and provides results to patients within a day of testing, which has been replicated globally [44]. Recently, a ‘Walk-thru’ testing method was rolled out for urban areas, which requires an even smaller space and shorter testing time.

4.7. Surveillance and contact tracing

After the MERS epidemic, Korea built its system for real-time surveillance and extensive contact tracing [3,7,13,29]. The IDCPA mandated KCDC and local governments to establish a team of epidemic intelligence service (EIS) officers to conduct epidemiological investigations without delay in the case of a possible infectious disease outbreak [13,23,29,36]. Contact tracing is heavily reliant on the use of information communication and technology (ICT), which is enabled by public-private partnerships with telecommunications companies and researchers in order to achieve real-time data and surveillance.

Transparent disclosure of real-time information to the public, mandated by the IDCPA, has been critical [3,29,32]. Private developers utilized the public data from KCDC to create innovative mobile apps and dashboards, allowing extensive contact tracing and real-time surveillance [13,31,32]. The data and apps were also used to update the general public. For instance, the database discloses the status of COVID-19 cases by cities and provinces, and includes maps that direct users to the nearest testing facilities and mask vendors, as well as information around ‘clean zones’ - places that have been disinfected following visits by confirmed patients [13,14]. This comprehensive digital contact tracing allowed accurate and early case detection, which enabled the country to control the outbreak within weeks.

Successful contact tracing and surveillance came with a price, however. Under the Personal Information Protection Act (PIPA), Korea can impose strict compliance requirements on entities that collect any information that could be used to identify a specific person [52]. The government can collect and use data without the need to obtain consent [37]. Although initially this was not well-received from the public, after experiencing MERS, the general public quickly learned to accept their privacy concerns. We acknowledge that Korea’s approach to data collection, surveillance, and contract tracing may not be replicable to many and may be frustrated by their personal data protection laws.

4.8. Isolation

South Korea’s strict quarantine and isolation measures have been one of the hallmarks to contain COVID-19. According to a study by the University of Southampton, early detection and isolation of cases were estimated to prevent more infections than travel restrictions [17,53]. Due to surging cases in the country, the government adopted a tiered system to separate the sick from the healthy. The severely ill and elderly are sent to hospitals. Moderately sick people are sent to an isolation center where traced and monitored. Asymptotic cases are asked to self-quarantine at home. International arrivals are also subject to mandatory testing and two weeks of mandatory quarantine and self-isolation. After the Daegu church incident, the local government ordered church members to self-isolate and be tested with the help of robust contact tracing [17]. After this outbreak, the ill individuals were isolated or hospitalized, and asymptomatic contacts were self-quarantined and monitored. At the same time, the Korean government established dedicated facilities for isolation, which transformed certain health facilities into temporary isolation wards to relieve hospital bed shortages [3,17]. Although testing and tracing are critical, without an effective strategy to isolate the sick from the healthy, the virus might be still spreading.

5. Discussion

Early and rapid response for COVID-19 made it possible for Korea to rapidly flatten the first epidemic curve in early 2020 despite proximity to China. Even during the latest surge in December 2020, the level of new infections was substantially smaller than what was expected by the prediction models by Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) [54] and lower than most other OECD countries [55]. Our evidence shows that a major factor that enabled a successful Korean response to the epidemic is its recent history of coping with MERS. This history led to institutional reforms and transparent governance that was put into place prior to COVID-19 and which made Korea’s systematic response more effective.

The revision of the IDCP Act following Korea’s 2015 MERS outbreak was a key step to develop the capacity for extensive contact tracing, public disclosure of information, and the coordination of central and local governments with the leadership of KCDC. In a health emergency like COVID-19, leadership and authority by the central government was able to quickly increase the response capacity of the country, as compared to a bottom-up approach in a highly decentralized system, like the United States [31].

A spillover effect of the MERS outbreak was an openness to making rapid legislative changes to the disease control act and a tolerance with trial-and-error as the situation evolved [4]. Initially all those who tested positive for COVID-19 were hospitalized. However, hospitalization of all patients overloaded the health system, resulting in a shortage of beds and health workers for severe COVID-19 patients, especially Daegu, where a large outbreak had occurred. After some patients died at home waiting for hospitalization, the government quickly responded, and patients were prioritized based on severity and reallocated to other provinces. Large suburban residential buildings were transformed to house patients with milder symptoms whose condition was evaluated daily by a physician. Heightened flexibility in the face of a crisis enabled passage of long-stalled health system reforms, including telemedicine, which was temporarily allowed in a limited scope to protect patients with existing conditions and minimize the exposure of health providers.

Transparent communication was essential as it helped the public trust the government and comply with government recommendations. Most people voluntarily followed government recommendations on social distancing, wearing masks, hand washing, cancelling meetings, working from home and did so without major restrictive measures. The popularity of President Moon Jae-In and his party increased due to the rapid and successful response to the pandemic. This contributed to the landslide victory of the President’s party in the general election on April 15, resulting in the lowest number of seats by the conservative (opposition) party in the National Assembly in 30 years.

From the beginning of the response to COVID-19, there was a debate about border closure, especially whether to restrict entry of visitors from China. Taiwan and Singapore implemented a restriction against Chinese visitors in early February. The South Korean government’s reluctance to introduce the ban on entry from China, except for visitors from Wuhan, was related to the consideration of its sensitive political relations with China. More importantly, Korea is an open economy and its supply chains are very closely linked with China. The government was worried about the potentially negative impact that the closure of its border could have on the Korean economy in the long run.

Amid its “success”, Korea too, however, faces myriad challenges. First, protecting the vulnerable population has been a struggle [4]. Even after transmission among the general population declined, outbreaks in long-term care hospitals and nursing homes continued. Self-employed, temporary workers and employees in certain industries who could not work from home were at higher risk from COVID-19. s, disclosure of highly detailed information on the restaurants and shops that had positive cases has had a sustained impact on affected business establishments. Lastly, the role of public health care providers became increasingly critical [4]. Although all private health care providers are part of the NHI system, they were less willing to treat COVID-19 patients. Allocation of COVID-19 patients and coordination among health providers could have been more seamless if Korea had more public providers, which currently account for only about 10 % of total providers.

Although the Korean response to COVID-19 has worked effectively and there’s much to learn from, it is critical that other countries to consider their own political and social context when applying strategies learned from South Korea as it may be difficult to emulate. There are, however, some important lessons from Korea that can provide important policy implications. Preparing a legal foundation and infrastructure for infectious disease control can be a key precondition to establishing and empowering dedicated government agencies with high capacity for infectious disease prevention and control. Having the political capability to quickly modify legal infrastructure as circumstances evolved was equally important. A policy such as extensive contact tracing can be quite contentious, thus it will be more effective if it is based on broadly supported legislation and social consensus. Mass scale testing was one of the most important strategies of Korea for early detection and isolation of cases, but this strategy cannot be implemented unless an infrastructure of laboratories, personnel, and reporting is in place.

This paper has systematically highlighted capabilities that sped the implementation of COVID-19 control. However, as mentioned, there’s no one-size-fits-all recipe. Each country should take stock of their strengths and gaps in a health system’s ability to prevent, detect, and respond. And they need to shore up their capability deficits and the country needs to strengthen their infectious disease prevention and control measures as COVID-19 will not be the last one coming.

6. Conclusion

This systematic assessment of South Korea’s capabilities to control the virus highlights the importance of Korea’s ‘pre-existing enablers,’ which allowed it to implement COVID-19 control policies that were highly successful. Korea embraced lessons learned from its past brush with MERS and rebuilt stronger legal and institutional foundations for effective infectious disease preparedness and response. Although the story of COVID-19 has not ended and will continue to evolve, we hope that the ‘core capability framework’ outlined here and illustrated by Korea provides a platform for other countries to assess their pre-existing capabilities so they can make their health systems more resilient to coming challenges.

Funding source

The authors did not receive any funding for the paper.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful for the support of DB from the Robert Wood Johnson (RWJ) Foundation (grant #78116).

Footnotes

Open Access for this article is made possible by a collaboration between Health Policy and The European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies.

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2021.02.011.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.IMF . World Economic Outlook; 2020. World economic outlook, april 2020: the great lockdown. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beech H. New York Times; 2020. Tracking the coronavirus: how crowded Asian cities tackled an epidemic. March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Health . In: Our world in data. ALapot Ei G, editor. 2020. EiG. Health.https://ourworldindata.org/covid-exemplar-south-korea Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwon. S. Global Hs, 2020. Available from: https://healthsystemsglobal.org/news/covid-19-lessons-from-south-korea/.

- 5.Oh J., Lee J.-K., Schwarz D., Ratcliffe H.L., Markuns J.F., Hirschhorn L.R. National response to COVID-19 in the Republic of Korea and lessons learned for other countries. Health Systems & Reform. 2020;6(1):e–1753464. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2020.1753464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moradi H., Vaezi A. Lessons learned from Korea: COVID-19 pandemic. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 2020;41(7):873–874. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim J.-H.A., Ahreum Julia Oh, Jackie Seungju. 2020. Emerging covid-19 success story: South Korea learned the lessons of MERS. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song J.-Y., Yun J.-G., Noh J.-Y., Cheong H.-J., Kim W.-J. Covid-19 in South Korea — challenges of subclinical manifestations. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382(19):1858–1859. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajan S., Cylus J., McKee M. What do countries need to do to implement effective ‘find, test, trace, isolate and support’ systems? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2020;113:245–250. doi: 10.1177/0141076820939395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.2020. COVID-19 in Republic of Korea: MOHW: center disaster control management HQ (CDCMHQ)http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/en [Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ki M. Epidemiologic characteristics of early cases with 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) disease in Korea. Epidemiol Health. 2020;42(0) doi: 10.4178/epih.e2020007. e2020007-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.KCDC . 2020. COVID-19 in South Korea. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Health RoK . 2020. Flattening the curve on COVID-19: how Korea responded to a pandemic using ICT. April 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ministry of Health RoK . 2020. Tackling COVID-19: health, quarantine and economic measures. Korea. March 31 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi Y. 2020. COVID-19 in South Korea. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim D.W. 2021. Public scapegoat: the socio-political ecology of the Korean church during the COVID-19 Pandemic1. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim J.-H., An J.A.-R., Min P.-k, Bitton A., Gawande A.A. How South Korea responded to the COVID-19 outbreak in Daegu. NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery. 2020;1(4) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi S., Ki M. Estimating the reproductive number and the outbreak size of COVID-19 in Korea. Epidemiology Health. 2020;42(0) doi: 10.4178/epih.e2020011. e2020011-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sang-Hun M.Fa C. New York Times; 2020. How South Korea flattened the curve. April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dudel C., Riffe T., Acosta E., van Raalte A.A., Strozza C., Myrskyla M. Monitoring trends and differences in COVID-19 case fatality rates using decomposition methods: contributions of age structure and age-specific fatality. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238904. 2020.03.31.20048397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oh M.-D., Park W.B., Park S.-W., Choe P.G., Bang J.H., Song K.-H., et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome: what we learned from the 2015 outbreak in the Republic of Korea. The Korean Journal of Internal Medicine. 2018;33(2):233–246. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2018.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ha K.-M. A lesson learned from the MERS outbreak in South Korea in 2015. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2016;92(3):232–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee C., Ki M. Strengthening epidemiologic investigation of infectious diseases in Korea: lessons from the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome outbreak. Epidemiology and Health. 2015;37 doi: 10.4178/epih/e2015040. e2015040-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park M. Infectious disease-related laws: prevention and control measures. Epidemiology and Health. 2017;39 doi: 10.4178/epih.e2017033. e2017033-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park S., Choi G.J., Ko H. Information technology–based tracing strategy in response to COVID-19 in South Korea—privacy controversies. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee S. Vergassungsblog; 2020. Fighting COVID 19 – legal powers and risks: South Korea. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwon S. Thirty years of national health insurance in South Korea: lessons for achieving universal health care coverage. Health Policy Planning. 2008;24(1):63–71. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barroy H.W., Pescetto Ding, Kutzin Claudia, Joseph . WHO; Geneva, Swizerland: 2020. How to budget for COVID-19 response? [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee K.-M., Jung K. Factors influencing the response to infectious diseases: focusing on the case of SARS and MERS in South Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019;16(8):1432. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16081432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zatstrow M. Geographic. N, editor 2020.

- 31.Kim B. Lawfare and Brookings; 2020. Lessons for America: how South Korean authorities used law to fight the coronavirus. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noh J.-W., Yoo K.-B., Kwon Y.D., Hong J.H., Lee Y., Park K. Effect of information disclosure policy on control of infectious disease: MERS-CoV outbreak in South Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(1):305. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17010305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee D., Heo K., Seo Y. COVID-19 in South Korea: lessons for developing countries. World Development. 2020;135 doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim I., Lee J., Lee J., Shin E., Chu C., Lee S.K. KCDC risk assessments on the initial phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in Korea. Osong Public Health and Research Perspectives. 2020;11(2):67–73. doi: 10.24171/j.phrp.2020.11.2.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.You M. 2020. Risk perception by public on COVID-19: 4th wave. 2020 april 17. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaw R., Kim Y.-k, Hua J. Governance, technology and citizen behavior in pandemic: lessons from COVID-19 in East Asia. Progress in Disaster Science. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan H. Thomas Reuter; 2020. Pervasive personal data collection at the heart of South Korea’s COVID-19 success may not translate. [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Neill J. World Economic Forum; 2020. South Korea’s economy is doing better than any other OECD country. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bowden J. The Hill; 2020. South Korea sends 2M masks to US to fight coronavirus. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seo E., Mun E., Kim W., Lee C. Fighting the COVID-19 pandemic: onsite mass workplace testing for COVID-19 in the Republic of Korea. Annals of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2020;32(1) doi: 10.35371/aoem.2020.32.e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagelhout G.E., Hummel K., de Goeij M.C.M., de Vries H., Kaner E., Lemmens P. How economic recessions and unemployment affect illegal drug use: a systematic realist literature review. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2017;44:69–83. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Larsen M.S. COVID-19 has crushed everybody’s economy—except for South Korea’s. Foreign Policy. 2020 SEPTEMBER 16, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 43.You J. Lessons from South Korea’s Covid-19 policy response. The American Review of Public Administration. 2020;50(6-7):801–808. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kwon K.T., Ko J.-H., Shin H., Sung M., Kim J.Y. Drive-through screening center for COVID-19: a safe and efficient screening system against massive community outbreak. Journal of Korean Medical Science. 2020;35(11) doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Austermann F., Shen W., Slim A. Governmental responses to COVID-19 and its economic impact: a brief Euro-Asian comparison. Asia Europe Journal. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s10308-020-00577-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sang-Hun C. New York Times; 2020. South Korea goes to the polls, coronavirus pandemic or not. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wallheimer B. Chicago Booth Review; 2020. How South Korea limited COVID-19 deaths and economic damage. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park C-k, Pandemic TC, editors. SCMP. 2020. Available from: https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/health-environment/article/3087152/coronavirus-south-korea-grapples-new-infection.

- 49.Ock H.-j.S. The Korea Herald; 2020. Korea extends Level 2.5 social distancing campaign in Greater Seoul area. September 5, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harcourt J., Tamin A., Lu X., Kamili S., Sakthivel S., Murray J., et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 from patient with coronavirus disease, United States. Emerging Infectious Disease Journal. 2020;26(6):1266. doi: 10.3201/eid2606.200516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Data . 2020. OWi. Coronavirus (COVID-19) testing. [Google Scholar]

- 52.2011. Personal Information Protection Act (PIPA) [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lai S., Ruktanonchai N.W., Zhou L., Prosper O., Luo W., Floyd J.R., et al. Effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions for containing the COVID-19 outbreak in China. medRxiv. 2020 2020.03.03.20029843. [Google Scholar]

- 54.IHME . Evaluation C--IfHMa. 2020. COVID-19 projections. editor. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Choi Y. 2021. Available from: https://rpubs.com/YJ_Choi/KCOVID_Global.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.