Abstract

Background

Limited data are available about the predictors and outcomes associated with prolonged SARS-CoV-2 RNA shedding (VS).

Methods

A retrospective study including COVID-19 patients admitted to an Italian hospital between March 1 and July 1, 2020. Predictors of viral clearance (VC) and prolonged VS from the upper respiratory tract were assessed by Poisson regression and logistic regression analyses. The causal relation between VS and clinical outcomes was evaluated through an inverse probability weighted Cox model.

Results

The study included 536 subjects. The median duration of VS from symptoms onset was 18 days. The estimated 30-day probability of VC was 70.2%. Patients with comorbidities, lymphopenia at hospital admission, or moderate/severe respiratory disease had a lower chance of VC. The development of moderate/severe respiratory failure, delayed hospital admission after symptoms onset, baseline comorbidities, or D-dimer >1000 ng/mL at admission independently predicted prolonged VS. The achievement of VC doubled the chance of clinical recovery and reduced the probability of death/mechanical ventilation.

Conclusions

Respiratory disease severity, comorbidities, delayed hospital admission and inflammatory markers negatively predicted VC, which resulted to be associated with better clinical outcomes. These findings highlight the importance of prompt hospitalization of symptomatic patients, especially where signs of severity or comorbidities are present.

Keywords: Coronavirus; SARS-CoV-2; COVID-19, viral clearance, viral shedding; Risk factors

Introduction

The emergence and rapid spread of the COVID-19 outbreak, caused by SARS-CoV-2, has become a global health emergency and one of our century's greatest challenges. As of February 24, 2021, approximately 111 million confirmed cases and more than 2.4 million deaths had been reported worldwide (Anon, 2020).

Several reports have shown that the shedding profile of SARS-CoV-2 differs from other coronaviruses but is similar to that of the influenza virus (To et al., 2020, He et al., 2020). Viral RNA can be detected in the upper respiratory tract (URT) a few days before symptoms onset, subsequently peaks within the first week of infection, and then gradually declines over time (To et al., 2020, He et al., 2020, Wolfel et al., 2020). According to recent evidence, the median duration of SARS-CoV-2 shedding in the URT is 17 days (Cevik et al., 2020). However, longer durations, up to 83 days, have been described (Li et al., 2020a). In several studies, mostly conducted in small cohorts, prolonged viral RNA shedding (VS) has been variously associated with male sex (Xu et al., 2020), older age (Wang et al., 2020, Du et al., 2020), disease severity (Xu et al., 2020, Du et al., 2020, Zhou et al., 2020a, Liu et al., 2020a, Zheng et al., 2020), delayed hospital admission/therapy start after symptoms onset (Xu et al., 2020, Qi et al., 2020, Fu et al., 2020) and comorbidities (Fu et al., 2020).

Several studies have questioned the correlation between the duration of VS and the duration of infectivity, showing that live virus can be cultured from respiratory samples for a significantly shorter time compared to detection of viral RNA by molecular methods, with a probability of detecting infectious virus lower than 5% after 15 days from symptoms onset (Wolfel et al., 2020, van Kampen et al., 2021). Although these findings have led to the update of isolation criteria in several international guidelines (WHO, 2020, CDC, 2020), decisions on infection prevention are still widely guided by strategies based on viral RNA detection. Therefore, further investigation on duration of VS and factors associated with prolonged shedding carried out on larger populations,may help to improve clinical management of COVID-19 patients.

Based on a large cohort of patients with COVID-19 admitted to an Italian reference hospital, this study aimed to estimate the time to SARS-CoV-2 clearance from the URT, identify predictive factors of both viral clearance (VC) and prolonged VS, and explore associations between VC and clinical outcomes.

Methods

Study design and population

We undertook an observational, retrospective, single-centre study including all consecutive adult patients with a confirmed diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection, made by detection of viral RNA from a respiratory specimen, admitted to the National Institute for Infectious Diseases Lazzaro Spallanzani IRCCS (Rome, Italy) between March 1 and July 1, 2020. Patients who did not have a date for symptoms onset or at least one post-diagnosis follow-up nasopharyngeal (NPS) or throat swab (TS) for SARS-CoV-2 were excluded from the analysis.

Data collection

Epidemiological, demographic, clinical, and laboratory data and information on treatments and outcomes of all patients with a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis were collected and recorded using a standardized electronic database (ReCOVery study).

The study was approved by our local ethics committee.

Virological assessment and clinical management

For all included patients, the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed on at least 1 respiratory specimen by the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA through real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) targeting the E and RdRp viral genes (Corman et al., 2020). Respiratory tract specimens included were NPS, TS, sputum, bronchoaspirate (BAS) and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid. During hospitalization, all patients underwent follow-up NPS and TS to assess VC. The frequency of NPS or TS follow-up was an average of every 3 days (interquartile range [IQR] 1–4) but it was not completely consistent as it depended on the treating physician’s judgment and the hospital’s internal protocol. The therapeutic management of patients was based on internal hospital protocol, national and international guidelines and clinical judgment, according to the best evidence available at the time.

Definitions

VC was defined as negative RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 on 2 consecutive NPS or TS. We considered acceptable a negative viral RNA on a single NPS or TS if it was the last available sample.

Prolonged VS was defined as detecting SARS-CoV-2 RNA on respiratory specimens for >18 days (the median duration of VS in our population). We considered the longest shedders as those patients in whom the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA on respiratory specimens was ≥26 days (75° percentile of VS duration in our population).

We defined clinical recovery as being discharged from the hospital (including transfer to a non-acute healthcare facility) or weaning off oxygen in patients who underwent oxygen therapy during the hospitalization who had not needed it before admission.

The severity of respiratory disease was defined as mild, for a ratio of arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO2) to fractional inspired oxygen (FiO2) between ≤300 mmHg and >200 mmHg; moderate, PaO2/FiO2 ratio between ≤200 mmHg and >100 mmHg; severe, PaO2/FiO2 ratio ≤100 mmHg (ARDS Definition Task Force, 2012).

Statistical analysis

Continuous and categorical variables were expressed as medians with IQRs and as numbers (%), respectively. The cumulative probability of achieving VC was estimated by Kaplan–Meier curves in the overall population and after stratifying by the severity of respiratory disease developed during hospitalization. In this latter analysis, the differences between groups were compared by the log-rank statistic test. Multivariable Poisson regression analysis was used to assess independent risk factors of VC, and multivariable logistic regression analysis to identify predictive factors of prolonged VS. In both multivariable analyses, significant factors identified on univariate analysis and other a priori identified confounders (age, sex) were included as covariates in the multivariable models. The causal relation between the duration of VS and the probability of positive (clinical recovery) and negative (invasive mechanical ventilation or death) clinical outcomes were evaluated using an inverse probability weighted (IPW) multivariable Cox model. The following factors were a priori included as covariates in the model: sex, age, number of comorbidities, antiviral therapy (yes vs no), immunomodulatory therapy and PaO2/FiO2 ratio during hospitalization. In all the performed analysis, the date of symptoms onset was considered as the baseline date. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA (version 15.1, College Station, Texas, USA). A P-value <0.05 indicated conventional statistical significance.

Results

Patients’ characteristics at hospital admission, therapeutic aspects and main clinical outcomes

Overall, 630 adult subjects were admitted to our centre with a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis during the observation period. After excluding 94 patients for whom the date of symptoms onset was not available (n = 89) or who did not have any follow-up swabs after diagnosis (n = 5), a total of 536 patients were included in the analysis. The main characteristics at hospital admission are shown in Table 1 . The majority of subjects were male (64.6%), with a median age of 63 years (IQR 51–75). Most patients (63.8%) had at least one underlying concomitant disease, including diabetes (14%), hypertension (40.3%) and heart disease (24.6%). At hospital admission, which occurred within a median time of 8 days (IQR 4–11) from symptoms onset, 92% of patients had evidence of lung involvement, and approximately one third showed respiratory failure with a PaO2/FiO2 ratio of ≤300 mmHg. Antiviral therapy was started in 454 patients (84.7%), soon after hospital admission for most patients, with protease inhibitors in 25.3%, hydroxychloroquine in 18.3%, and protease inhibitors combined with hydroxychloroquine in 49.7%. A minority of patients (6.6%) were enrolled in randomized clinical trials and started remdesivir, most of them (83.3%) after initial antiviral therapy. Immunomodulatory therapy with cytokines inhibitors was given to 19.8% of patients and systemic corticosteroids to 41.8%, mostly (93.7%) in association with antivirals (specifically, in 61 patients with protease inhibitors, 22 with hydroxychloroquine, 107 with protease inhibitors plus hydroxychloroquine, and 20 with remdesivir).

Table 1.

Patients’ clinical characteristics on hospital admission, therapeutic aspects and main clinical outcomes.

| Clinical characteristics at hospital admission | Overall Sample (N = 536) |

|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 346 (64.6 %) |

| Age, years | |

| Median (IQR) | 63 (51–75) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| None | 194 (36.2 %) |

| 1 | 133 (24.8 %) |

| 2 | 78 (14.6 %) |

| ≥3 | 131 (24.4 %) |

| Diabetes | 75 (14.0 %) |

| Hypertension | 216 (40.3 %) |

| Cardiovascular | 132 (24.6 %) |

| Respiratory, including asthma | 94 (17.5 %) |

| Neoplasm | 54 (10.1 %) |

| Days from symptoms onset to hospital admission | |

| Median (IQR) | 8 (4–11) |

| Severe respiratory disease, n (%) | |

| PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300 mmHg | 175 (32.7 %) |

| PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 200 mmHg | 70 (13.1 %) |

| Radiologic evidence of pneumonia, n (%) | |

| yes | 493 (92.0 %) |

| Inflammatory index, n (%) | |

| Lymphocytes count < 1.0 × 109/L | 207 (38.6 %) |

| D-dimer > 103 ng/mL | 304 (56.7 %) |

| Serum Ferritin > 500 ng/mL | 206 (38.4 %) |

| Treatment and main outcomes during hospitalization | |

|---|---|

| Days from symptoms onset to antiviral therapy | |

| Median (IQR) | 8 (5–11) |

| Antiviral treatment, n (%) | |

| None | 82 (15.3 %) |

| Yes | 454 (84.7 %) |

|

115 (25.3 %) |

|

83 (18.3 %) |

|

226 (49.7 %) |

|

30 (6.6 %) |

|

5 (16.7 %) |

|

7 (23.3 %) |

|

6 (20.0 %) |

|

12 (40.0 %) |

| Immunomodulatory therapy, n (%) | |

| Cytokines inhibitors | 106 (19.8 %) |

| Corticosteroids | 224 (41.8 %) |

|

14 (6.3 %) |

|

210 (93.7 %) |

| Duration of viral shedding from symptoms onset, | |

| Median (IQR) | 18 (12–26) |

| Patients achieving viral clearance, n (%) | |

| Total | 359 (66.9 %) |

| Patients who developed respiratory failure during hospitalization, n (%) | |

| PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300 mmHg | 128 (23.8 %) |

| PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 200 mmHg | 75 (14.0 %) |

| Patients who needed respiratory support, n (%) | |

| Oxygen therapy | 403 (75.3 %) |

| NPPV | 133 (24.8 %) |

| IMV | 51 (9.5 %) |

| Hospitalization outcomes, n (%) | |

| Death | 63 (11.8 %) |

| Discharged at home | 372 (69.4 %) |

| Transferred to non-acute healthcare facility | 101 (18.8 %) |

| Death with positive NPS/TS | 46 (8.6 %) |

| Discharged/transferred with positive NPS/TS | 122 (24.4 %) |

| Hospitalization length, days | |

| Median (IQR) | 12 (7–20) |

| Follow-up, days | |

| Median (IQR) | 18 (12–26) |

Abbreviations: n, number; IQR, interquartile range; PaO2, arterial oxygen partial pressure; FiO2, fractional inspired oxygen; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; PI/b, boosted protease inhibitors; NPPV, Non-Invasive Positive Pressure Ventilation; IMV, Invasive Mechanical Ventilation, NPS, nasopharyngeal swab; TS, throat swab.

The median time of VC from URT was 18 days (IQR 12–26) from symptoms onset. Over a median time of hospitalization of 12 days (IQR 7–20), 473 patients (88.2%) were discharged or transferred to non-acute healthcare facilities, and 63 (11.8%) died. During hospitalization, 128 patients (23.8%) developed respiratory failure, which was moderate to severe (PaO2/FiO2 ratio ≤200 mmHg) in 75/128 patients. Supplemental oxygen was given to 403 patients (75.3%), including non-invasive positive pressure ventilation in 133 and invasive mechanical ventilation in 51 (Table 1). The majority of the longest shedders (≥26 days from symptoms onset) were male (65.4%) with a median age of 68 years (IQR 53–78), and 78.4% of them had at least 1 underlying concomitant disease. For the longest shedders, hospital admission occurred within a median of 12 days (7–24) and 37.4% of them had a PaO2/FiO2 ratio of ≤300 mmHg at admission.

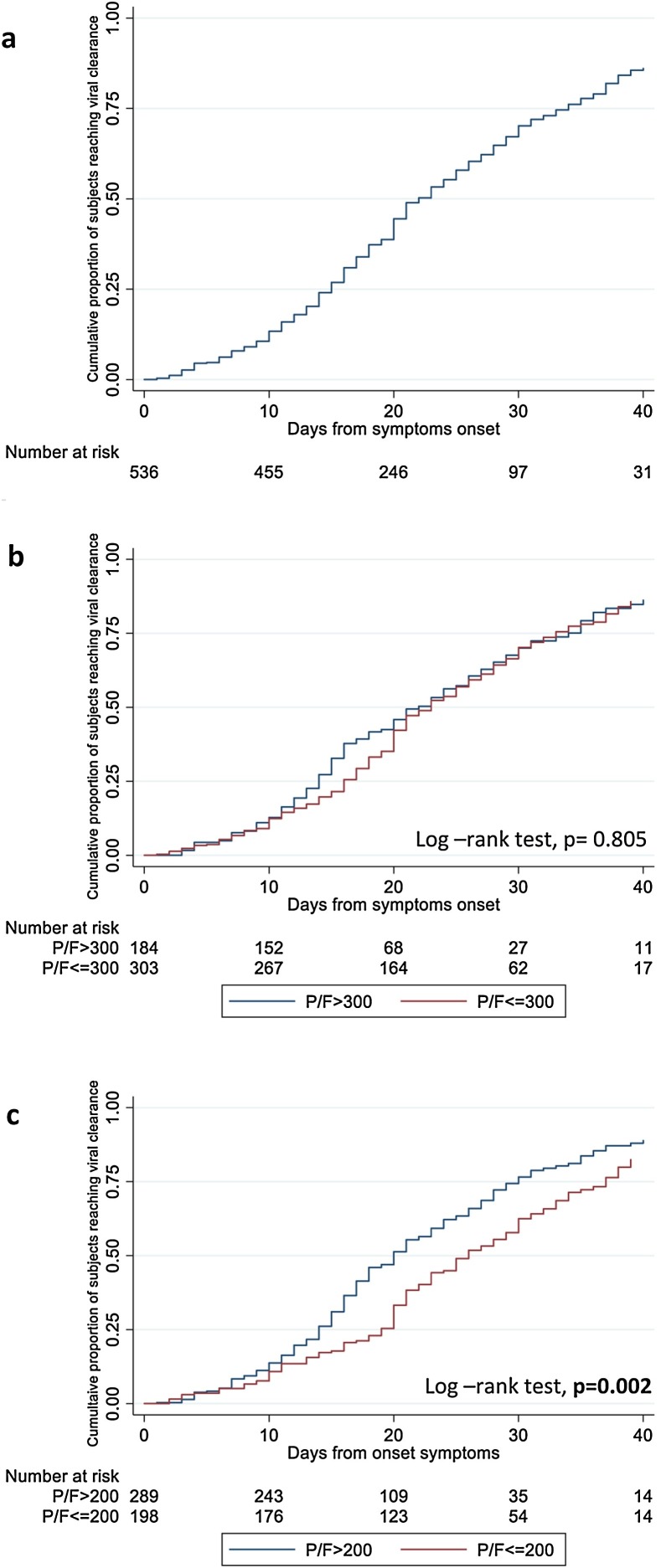

Probability of viral clearance and associated risk factors

Over a median follow-up of 18 days (IQR 12–26), 359 patients (66.9%) achieved VC. In 34 (9.5%) of these 359 patients the achievement of VC was considered after a single negative swab since it was the last available sample. Of note, four of these 34 patients died after the last negative follow-up specimen, while 8 had intermittent VS before the last available swab. The shortest duration of VS observed in our population was 1 day, while the longest was 73 days. In the overall population, the estimated probability of achieving VC at 20 days and 30 days from symptoms onset was 44.5% (95% CI: 40–49) and 70.2% (95% CI: 65–75), respectively (Figure 1 a). After stratifying by the severity of respiratory disease, the cumulative probability of VC from the URT was significantly lower in patients who developed moderate/severe respiratory failure (PaO2/FiO2 ratio ≤200 mmHg) compared to those who maintained a PaO2/FiO2 ratio of >200 mmHg during hospitalization (P = 0.002, Figure 1c). The probability of VC did not differ after stratifying for less severe respiratory failure (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves estimating the cumulative probability of viral clearance in total population (a) and after stratifying by the severity of respiratory disease [PaO2/FiO2 ratio ≤300 mmHg versus >300 mmHg (b) andPaO2/FiO2 ratio ≤200 mmHg versus >200 mmHg (c)].

At the multivariable Poisson regression analysis, patients who developed moderate/severe respiratory failure (PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 200 mmHg) either at hospital admission or during hospitalization were less likely to achieve VC (adjusted incidence rate ratio [aIRR] 0.42, 95% CI: 0.27−0.66, P < 0.001). Similarly, patients who had underlying comorbidities (aIRR 0.88 for each additional comorbidity, 95% CI: 0.80−0.96, P = 0.004) and lymphopenia (lymphocytes count below 1.0 × 109/L) at hospital admission (aIRR 0.75, 95% CI: 0.58−0.98, P = 0.032) were found to be associated with a lower probability of VC (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Predictive factors of viral clearance by Poisson regression analysis.

| Crude IRR (95 % CI) | p-value | Adjusted IRR (95 % CI) | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||||

| Male vs Female | 1.01 (0.82–1.26) | 0.904 | 1.03 (0.82–1.29) | 0.798 | |||

| Age | |||||||

| For 10 years older | 0.96 (0.90–1.02) | 0.217 | 1.03 (0.95–1.12) | 0.419 | |||

| Underlying comorbidities | |||||||

| For each more | 0.90 (0.84−0.97) | 0.005 | 0.88 (0.80−0.96) | 0.004 | |||

| Inflammatory index at hospital admission | |||||||

| Lymphocytes count < 1.0 × 109/L | 0.69 (0.54−0.87) | 0.002 | 0.75 (0.58−0.98) | 0.032 | |||

| D-dimer > 103 ng/mL | 1.16 (0.89–1.51) | 0.271 | |||||

| Serum Ferritin > 500 ng/mL | 1.07 (0.82–1.39) | 0.631 | |||||

| Severity of respiratory diseasea | |||||||

| PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 200 versus > 200 mmHg | 0.61 (0.47−0.79) | <0.001 | 0.42 (0.27−0.66) | <0.001 | |||

| Time from symptoms onset to admission | |||||||

| for 1 day more | 0.98 (0.97−0.99) | <0.001 | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | 0.378 | |||

| Antiviral therapya | |||||||

| Yes versus no | 2.81 (2.23–3.53) | <0.001 | 1.16 (0.77–1.74) | 0.490 | |||

| Corticosteroidsa | |||||||

| Yes versus no | 1.57 (1.25–1.95) | <0.001 | 1.12 (0.85–1.46) | 0.419 | |||

| Cytokines inhibitors | |||||||

| Yes versus no | 1.04 (0.81–1.33) | 0.783 | 0.95 (0.73–1.23) | 0.677 | |||

Abbreviations: IRR, incidence rate ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Time updated variable.

Risk factors for prolonged viral shedding

Overall, 258 patients showed detectable SARS-CoV-2 RNA in URT specimens for more than 18 days. Analysing predictive factors of prolonged VS by multivariable logistic regression analysis, having underlying comorbidities (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.25 for each additional comorbidity, 95% CI: 1.04–1.51, P = 0.019) and having developed moderate/severe respiratory failure (PaO2/FiO2 ratio ≤200 mmHg) during hospitalization (aOR 2.65, 95% CI: 1.39–5.05, P = 0.003) were significantly associated to increased odds of slower VC. Additionally, delayed hospital admission after illness onset (aOR 1.18 for each additional day of symptoms before hospitalization, 95% CI: 1.12-1.23, P < 0.001) and a high value of D-dimer (above 1000 ng/mL) at admission (aOR 1.76, 95% CI: 1.04–2.99, P = 0.035) significantly predicted a prolonged VS (Table 3 ). Finally, the use of steroid therapy showed a trend toward significance as a predictive factor of prolonged VS (aOR 1.79, 95% CI: 0.95–3.39, P = 0.073).

Table 3.

Predictive factors of prolonged viral shedding (> 18 days) by Logistic regression analysis (on 438 patientsa).

| Crude OR (95 % CI) | p-value | Adjusted OR (95 % CI) | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||||

| Female vs Male | 0.72 (0.48–1.08) | 0.112 | 0.90 (0.55–1.46) | 0.668 | |||

| Age | |||||||

| For 10 years older | 1.15 (1.02–1.30) | 0.022 | 1.02 (0.85–1.23) | 0.804 | |||

| Underlying comorbidities | |||||||

| For each more | 1.22 (1.07–1.39) | 0.003 | 1.25 (1.04–1.51) | 0.019 | |||

| Inflammatory index at hospital admission | |||||||

| Lymphocytes count < 1.0 × 109/L | 1.05 (0.77–1.42) | 0.764 | |||||

| D-dimer > 103 ng/mL | 0.90 (0.84−0.96) | 0.002 | 1.76 (1.04–2.99) | 0.035 | |||

| Serum Ferritin > 500 ng/mL | 0.96 (0.90–1.02) | 0.153 | |||||

| Severity of respiratory disease at hospital admission, | |||||||

| PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 200 versus > 200 mmHg | 2.32 (1.23–4.39) | 0.010 | 0.86 (0.38–1.95) | 0.711 | |||

| Severity of respiratory disease during hospitalization, | |||||||

| PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 200 versus > 200 mmHg | 3.05 (1.98–4.69) | <0.001 | 2.65 (1.39–5.05) | 0.003 | |||

| Time from symptoms onset to admission | |||||||

| for 1 day more | 1.13 (1.09–1.18) | <0.001 | 1.18 (1.12–1.23) | <0.001 | |||

| Antiviral therapy | |||||||

| Yes versus no | 1.24 (0.74–2.09) | 0.413 | 1.75 (0.81–3.81) | 0.158 | |||

| Corticosteroids | |||||||

| Yes versus no | 2.75 (1.64–4.59) | <0.001 | 1.79 (0.95–3.39) | 0.073 | |||

| Cytokines inhibitors | |||||||

| Yes versus no | 2.77 (1.86–4.13) | <0.001 | 1.53 (0.90–2.59) | 0.116 | |||

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Excluding patients who died before 18 days without virological clearance and those discharged with viral shedding before 18 days in whom the data about the follow-up swabs performed after hospitalization were not available.

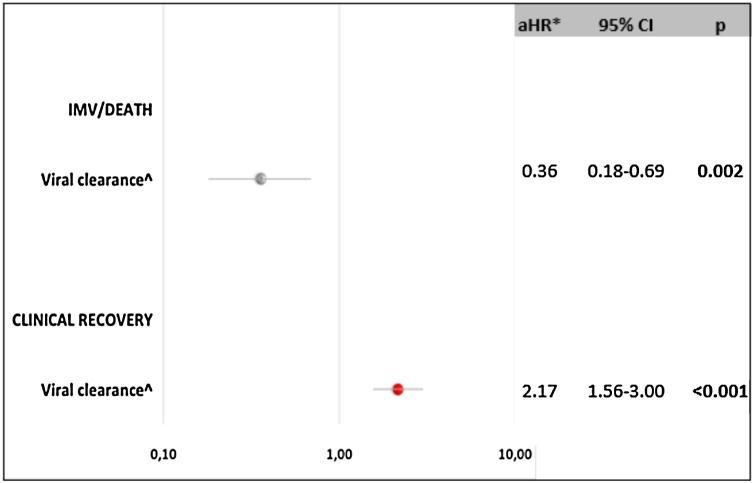

Association between viral RNA shedding and clinical outcomes

The potential causal relationship between the achievement of VC and the occurrence of the main clinical outcomes was explored by a multivariable IPW Cox model (Figure 2 ). After controlling for the main confounding factors listed in Methods, we found that VC strongly predicted clinical recovery (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 2.17, 95% CI: 1.56–3.00, P < 0.001) and reduced the probability of invasive mechanical ventilation or death by more than 60% (aHR 0.36, 95% CI: 0.18−0.69, P = 0.002).

Figure 2.

Causal relation between viral clearance and main clinical outcomes by Inverse Probability Weighted Cox regression Analysis.

Abbreviations: aHRadjusted hazard ratio; CIconfidence interval; IMVinvasive mechanical ventilation

*After adjusting for gender, age, number of comorbidities, use of antiviral therapy (yes versus no), use of cytokines inhibitors (yes versus no), use of steroids (yes versus no), PaO2/FiO2 ratio (≤200 mmHg versus >200) during hospitalization (time updated variable).

Discussion

This retrospective study focused on the duration of VS from the URT and the factors associated with both VC and prolonged VS.

In our cohort the median duration of VS, from symptoms onset to VC, was 18 days. This finding is in line with a recent systematic review and metanalysis, which reported a mean duration of viral detection from the URT of 17 days, from an analysis of 43 studies including 3229 subjects (Cevik et al., 2020). However, the median duration of SARS-CoV-2 shedding in the respiratory tract varies widely in the different studies, ranging between 11 and 31 days (Li et al., 2020a, Xu et al., 2020, Zhou et al., 2020a, Qi et al., 2020, Zhou et al., 2020b). This variability could be partially explained by the heterogeneity of study populations, particularly regarding the clinical conditions, and the different kind of specimens considered.Similarly, also the maximum persistence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA differ significantly among the studies, with the longest described VS duration of 83 days, lasting even after symptoms resolution and seroconversion (Li et al., 2020a). Our study found a maximum VS duration of 73 days, one of the longest reported to date. In our cohort, patients with the longest VS duration were mainly characterized by advanced age, underlying comorbidities and a delayed hospital admission (>10 days after illness onset) and a severe clinical presentation of the disease.

In the current study, the severity of illness, delayed admission to hospital after symptoms onset, presence of underlying comorbidities and alteration of inflammatory index at hospital admission were identified as independent risk factors of delayed VC and/or prolonged VS.

The association between the severity of COVID-19 disease and duration of VS has already been widely reported (Xu et al., 2020, Du et al., 2020, Zhou et al., 2020a, Liu et al., 2020a, Zheng et al., 2020). Although several studies have described similar (To et al., 2020, Cevik et al., 2020, Yilmaz et al., 2021) or even longer (Cevik et al., 2020) duration of VS in the URT in mild compared to severe cases, the majority of reports found that patients with more severe illness shed viral RNA for a longer period (Cevik et al., 2020, Xu et al., 2020, Du et al., 2020, Zhou et al., 2020a, Liu et al., 2020a, Zheng et al., 2020, Fontana et al., 2020). However, the definition of severity among these studies is not homogeneous. Most studies evaluated the differences in VS duration between mild and severe cases (Du et al., 2020, Liu et al., 2020a, Zheng et al., 2020). Conversely, Zhou et al. compared severe versus critical cases (Zhou et al., 2020), and in Xu et al., invasive mechanical ventilation was used as a proxy for illness severity (Xu et al., 2020). In this study, we used PaO2/FiO2 ratio to define disease severity, according to the Berlin definition of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS Definition Task Force, 2012). We found that a PaO2/FiO2 ratio of ≤200, corresponding to moderate to severe respiratory failure (ARDS Definition Task Force, 2012), was associated with a delayed VC/prolonged VS. Of note, in a recent study, the correlation between disease severity and longer persistence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in respiratory tract samples has also been confirmed using virus cultures, which are considered a more reliable index of infectivity compared to molecular methods (van Kampen et al., 2021). The association between illness severity and prolonged VS, which has previously been described for MERS and influenza virus (Oh et al., 2016, Wang et al., 2018), might be partially explained by the higher viral loads reported in severe COVID-19 cases compared to mild ones (He et al., 2020, Liu et al., 2020a, Zheng et al., 2020).

Noteworthy, in the current study, the relationship between VS duration and the clinical course of COVID-19 appeared to be bidirectional. Consistent with data from other coronavirus and influenza virus infections (Wang et al., 2018, Arabi et al., 2017), we found that VC from the URT almost doubled the odds of clinical recovery and reduced the risk of worse clinical outcomes. The ongoing pro-inflammatory stimulus due to the persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in the respiratory tract and the resulting organ damage may contribute to explaining this finding.

Although comorbidities have been identified as one of the main prognostic factors for COVID-19 severity, only a few studies have reported an association with the duration of VS (Fu et al., 2020, Xiao et al., 2020). Several conditions, including coronary heart disease (Fu et al., 2020), hypertension (Xiao et al., 2020) and diabetes (Xiao et al., 2020), have been linked to a longer persistence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in respiratory tract. Our study did not find an association between specific comorbidities and the persistence of viral RNA. Rather we observed that patients with underlying comorbidities were more likely to have both slower VC and prolonged viral detection with an increased risk for each additional comorbidity.

In our cohort, we found that deferred hospital admission after the onset of symptoms increased the probability of prolonged VS by approximately 15% per day. This finding, already reported in previous studies (Xu et al., 2020, Qi et al., 2020, Li et al., 2020b, Xudan et al., 2020), may suggest a potential effect of antiviral treatments on SARS-CoV-2 clearance, as demonstrated for influenza A infection (Wang et al., 2018). This hypothesis is also supported by the viral dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 characterized by a peak in viral load at the time of, or shortly before, symptoms onset. However, contrary to influenza A infection, none of the antiviral regimens considered in this study have shown clear advantages in limiting the duration of viral shedding (Cevik et al., 2020). Additionally, in our cohort, the use of antiviral therapy was not associated with either the probability of VC or prolonged VS. An alternative explanation for this result is that the application of general supportive measures alone might have reduced the length of VS. The association between the time from symptoms onset to hospitalization and the duration of SARS-CoV-2 shedding is a key finding of this study which highlights the importance of a medical strategy based on rapid testing of symptomatic patients and prompt hospitalization and management of the infected patients.

The role of corticosteroids in the management of COVID-19 is still a matter of debate. Although data from recent randomised clinical trials have shown a potential beneficial effect of steroid therapy on survival in severe/critically-ill patients (The WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group, 2020, RECOVERY Collaborative Group et al., 2020), their impact on VS remains more uncertain, with some evidence indicating a possible association with a delayed VC (van Paassen et al., 2020). In our cohort, we did not observe a clear association between the use of corticosteroids and a prolonged VS, as previously described in both SARS-CoV-2 and other coronavirus infections (Li et al., 2020b, Arabi et al., 2018). However, further evidence from ongoing clinical trials might better clarify the role of corticosteroids in COVID-19 treatment.

Finally, alteration of pro-inflammatory markers, and particularly lymphopenia and elevated D-dimer, at the time of hospital admission was found to be an independent risk factor of prolonged VS. Given the role of the immune response in the clinical course of COVID-19, these indices have already been identified as markers of disease severity (Zhou et al., 2020a), and a recent study found that the alteration of the inflammatory markers was more frequent in patients with prolonged VS(Qi et al., 2020, Liu et al., 2020b). However, an independent association with VS has not previously been observed, and further studies are warranted to confirm this result.

Our study has several limitations. First, the study could be prone to bias related to unmeasured confounders due to its observational nature. Second, the retrospective collection of medical records may have introduced bias due to potentially inaccurate data reporting. Third, the estimated duration of VS could have been influenced by heterogeneity in the frequency of specimen collection and the type of respiratory specimen used. Additionally, the lack of any quantitative determination of viral load, even through an indirect measure such as cycle-threshold value, do not allow us to draw any conclusion about the potential infectiousness of long-term shedders. Finally, the single-centre nature of the study may limit the generalizability of our findings. However, the study's main strength is its large sample size; to our knowledge, this is one of the largest cohorts in which the duration of SARS-CoV-2 RNA shedding has been investigated. Thus, this study provides significant information on the dynamics of VS and the determinants of delayed VC.

In conclusion, through a large retrospective cohort study, we found that severity of respiratory disease, delayed admission to hospital after the onset of symptoms, presence of underlying comorbidities and alteration of pro-inflammatory markers at the time of hospitalization independently predicted a longer persistence of SARS-CoV-RNA in the upper respiratory tract. Furthermore, our data showed that a more rapid achievement of VC was independently associated with better clinical outcomes and survival. These findings suggest a more rapid VC and limit on the worse clinical outcomes could be achieved through a medical strategy based on rapid testing of symptomatic subjects and prompt hospitalization and therapy initiation for patients with a confirmed diagnosis, especially where signs of severity and concomitant medical conditions are present. Infection control and prevention criteria might also consider the disease's clinical course, addressing test-based isolation strategies or longer isolation periods for patients with severe/critical COVID-19.

Author contributions

AM was a major contributor in writing the manuscript; PL analysed data; CC, RG, EL, AC, MBV, FT, SC, LL, FDG, GDO, FP, EN, CA, NP, GI, FV, EG, MRC have participated in the research and acquisition of data; AA made substantial contributions to the conception of the work and interpretation of data.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest

Funding

This work was supported by Line one - Ricerca Corrente ‘Infezioni Emergenti e Riemergenti’ and by Progetto COVID 2020 12,371,675 both funded by Italian Ministry of Health.

Acknowledgments

Collaborators Members of the National Institute for Infectious Diseases (INMI) ReCOVeRI study group: Maria Alessandra Abbonizio, Amina Abdeddaim, Elisabetta Agostini, Chiara Agrati, Fabrizio Albarello, Gioia Amadei, Alessandra Amendola, Andrea Antinori, Maria Assunta Antonica, Mario Antonini, Tommaso Ascoli Bartoli, Francesco Baldini, Raffaella Barbaro, Barbara Bartolini, Rita Bellagamba, Martina Benigni, Nazario Bevilacqua, Gianluigi Biava, Michele Bibas, Licia Bordi, Veronica Bordoni, Evangelo Boumis, Marta Branca, Rosanna Buonomo, Donatella Busso, Marta Camici, Paolo Campioni, Flaminia Canichella, Maria Rosaria Capobianchi, Alessandro Capone, Cinzia Caporale, Emanuela Caraffa, Ilaria Caravella, Fabrizio Carletti, Concetta Castilletti, Adriana Cataldo, Stefano Cerilli, Carlotta Cerva, Roberta Chiappini, Pierangelo Chinello, Maria Assunta Cianfarani, Carmine Ciaralli, Claudia Cimaglia, Nicola Cinicola, Veronica Ciotti, Stefania Cicalini, Francesca Colavita, Angela Corpolongo, Massimo Cristofaro, Salvatore Curiale, Alessandra D’Abramo, Cristina Dantimi, Alessia De Angelis, Giada De Angelis, Maria Grazia De Palo, Federico De Zottis, Virginia Di Bari, Rachele Di Lorenzo, Federica Di Stefano, Gianpiero D’Offizi, Davide Donno, Francesca Evangelista, Francesca Faraglia, Anna Farina, Federica Ferraro, Lorena Fiorentini, Andrea Frustaci, Matteo Fusetti, Vincenzo Galati, Roberta Gagliardini, Paola Gallì, Gabriele Garotto, Ilaria Gaviano, Saba Gebremeskel Tekle, Maria Letizia Giancola, Filippo Giansante, Emanuela Giombini, Guido Granata, Maria Cristina Greci, Elisabetta Grilli, Susanna Grisetti, Gina Gualano, Fabio Iacomi, Marta Iaconi, Giuseppina Iannicelli, Carlo Inversi, Giuseppe Ippolito, Eleonora Lalle, Maria Elena Lamanna, Simone Lanini, Daniele Lapa, Luciana Lepore, Raffaella Libertone, Raffaella Lionetti, Giuseppina Liuzzi, Laura Loiacono, Andrea Lucia, Franco Lufrani, Manuela Macchione, Gaetano Maffongelli, Alessandra Marani, Luisa Marchioni, Andrea Mariano, Maria Cristina Marini, Micaela Maritti, Annelisa Mastrobattista, Ilaria Mastrorosa, Giulia Matusali, Valentina Mazzotta, Paola Mencarini, Silvia Meschi, Francesco Messina, Sibiana Micarelli, Giulia Mogavero, Annalisa Mondi, Marzia Montalbano, Chiara Montaldo, Silvia Mosti, Silvia Murachelli, Maria Musso, Michela Nardi, Assunta Navarra, Emanuele Nicastri, Martina Nocioni, Pasquale Noto, Roberto Noto, Alessandra Oliva, Ilaria Onnis, Sandrine Ottou, Claudia Palazzolo, Emanuele Pallini, Fabrizio Palmieri, Giulio Palombi, Carlo Pareo, Virgilio Passeri, Federico Pelliccioni, Giovanna Penna, Antonella Petrecchia, Ada Petrone, Nicola Petrosillo, Elisa Pianura, Carmela Pinnetti, Maria Pisciotta, Pierluca Piselli, Silvia Pittalis, Agostina Pontarelli, Costanza Proietti, Vincenzo Puro, Paolo Migliorisi Ramazzini, Alessia Rianda, Gabriele Rinonapoli, Silvia Rosati, Dorotea Rubino, Martina Rueca, Alberto Ruggeri, Alessandra Sacchi, Alessandro Sampaolesi, Francesco Sanasi, Carmen Santagata, Alessandra Scarabello, Silvana Scarcia, Vincenzo Schininà, Paola Scognamiglio, Laura Scorzolini, Giulia Stazi, Giacomo Strano,Fabrizio Taglietti, Chiara Taibi, Giorgia Taloni, Tetaj Nardi, Roberto Tonnarini, Simone Topino, Martina Tozzi, Francesco Vaia, Francesco Vairo, Maria Beatrice Valli, Alessandra Vergori, Laura Vincenzi, Ubaldo Visco-Comandini, Serena Vita, Pietro Vittozzi, Mauro Zaccarelli, Antonella Zanetti and Sara Zito.

Contributor Information

For the INMI Recovery study group:

Maria Alessandra Abbonizio, Amina Abdeddaim, Elisabetta Agostini, Chiara Agrati, Fabrizio Albarello, Gioia Amadei, Alessandra Amendola, Andrea Antinori, Maria Assunta Antonica, Mario Antonini, Tommaso Ascoli Bartoli, Francesco Baldini, Raffaella Barbaro, Barbara Bartolini, Rita Bellagamba, Martina Benigni, Nazario Bevilacqua, Gianluigi Biava, Michele Bibas, Licia Bordi, Veronica Bordoni, Evangelo Boumis, Marta Branca, Rosanna Buonomo, Donatella Busso, Marta Camici, Paolo Campioni, Flaminia Canichella, Maria Rosaria Capobianchi, Alessandro Capone, Cinzia Caporale, Emanuela Caraffa, Ilaria Caravella, Fabrizio Carletti, Concetta Castilletti, Adriana Cataldo, Stefano Cerilli, Carlotta Cerva, Roberta Chiappini, Pierangelo Chinello, Maria Assunta Cianfarani, Carmine Ciaralli, Claudia Cimaglia, Nicola Cinicola, Veronica Ciotti, Stefania Cicalini, Francesca Colavita, Angela Corpolongo, Massimo Cristofaro, Salvatore Curiale, Alessandra D’Abramo, Cristina Dantimi, Alessia De Angelis, Giada De Angelis, Maria Grazia De Palo, Federico De Zottis, Virginia Di Bari, Rachele Di Lorenzo, Federica Di Stefano, Gianpiero D’Offizi, Davide Donno, Francesca Evangelista, Francesca Faraglia, Anna Farina, Federica Ferraro, Lorena Fiorentini, Andrea Frustaci, Matteo Fusetti, Vincenzo Galati, Roberta Gagliardini, Paola Gallì, Gabriele Garotto, Ilaria Gaviano, Saba Gebremeskel Tekle, Maria Letizia Giancola, Filippo Giansante, Emanuela Giombini, Guido Granata, Maria Cristina Greci, Elisabetta Grilli, Susanna Grisetti, Gina Gualano, Fabio Iacomi, Marta Iaconi, Giuseppina Iannicelli, Carlo Inversi, Giuseppe Ippolito, Eleonora Lalle, Maria Elena Lamanna, Simone Lanini, Daniele Lapa, Luciana Lepore, Raffaella Libertone, Raffaella Lionetti, Giuseppina Liuzzi, Laura Loiacono, Andrea Lucia, Franco Lufrani, Manuela Macchione, Gaetano Maffongelli, Alessandra Marani, Luisa Marchioni, Andrea Mariano, Maria Cristina Marini, Micaela Maritti, Annelisa Mastrobattista, Ilaria Mastrorosa, Giulia Matusali, Valentina Mazzotta, Paola Mencarini, Silvia Meschi, Francesco Messina, Sibiana Micarelli, Giulia Mogavero, Annalisa Mondi, Marzia Montalbano, Chiara Montaldo, Silvia Mosti, Silvia Murachelli, Maria Musso, Michela Nardi, Assunta Navarra, Emanuele Nicastri, Martina Nocioni, Pasquale Noto, Roberto Noto, Alessandra Oliva, Ilaria Onnis, Sandrine Ottou, Claudia Palazzolo, Emanuele Pallini, Fabrizio Palmieri, Giulio Palombi, Carlo Pareo, Virgilio Passeri, Federico Pelliccioni, Giovanna Penna, Antonella Petrecchia, Ada Petrone, Nicola Petrosillo, Elisa Pianura, Carmela Pinnetti, Maria Pisciotta, Pierluca Piselli, Silvia Pittalis, Agostina Pontarelli, Costanza Proietti, Vincenzo Puro, Paolo Migliorisi Ramazzini, Alessia Rianda, Gabriele Rinonapoli, Silvia Rosati, Dorotea Rubino, Martina Rueca, Alberto Ruggeri, Alessandra Sacchi, Alessandro Sampaolesi, Francesco Sanasi, Carmen Santagata, Alessandra Scarabello, Silvana Scarcia, Vincenzo Schininà, Paola Scognamiglio, Laura Scorzolini, Giulia Stazi, Giacomo Strano, Fabrizio Taglietti, Chiara Taibi, Giorgia Taloni, Tetaj Nardi, Roberto Tonnarini, Simone Topino, Martina Tozzi, Francesco Vaia, Francesco Vairo, Maria Beatrice Valli, Alessandra Vergori, Laura Vincenzi, Ubaldo Visco-Comandini, Serena Vita, Pietro Vittozzi, Mauro Zaccarelli, Antonella Zanetti, and Sara Zito

References

- Anon . 2020. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available at https://covid19.who.int/. Last accessed 24.02.2021. [Google Scholar]

- Arabi Y.M., Al-Omari A., Mandourah Y. Critically Ill Patients with the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(10):1683–1695. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabi Y.M., Mandourah Y., Al‐Hameed F. Corticosteroid therapy for critically ill patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(6):757–767. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1172OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARDS Definition Task Force Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC . 2020. Duration of Isolation and Precautions for Adults with COVID-19. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/duration-isolation.html#cecommendations Last access 06 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cevik M., Tate M., Lloyd O. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV viral load dynamics, duration of viral shedding, and infectiousness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Microbe. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30172-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corman V.M., Landt O., Kaiser M. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Eurosurveillance. 2020 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du X., Yu X., Li Q. Duration for carrying SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19 patients. J Infect. 2020;81(1):e78–e79. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana L.M., Villamagna A.H., Sikka M.K. Understanding viral shedding of severe acute respiratory coronavirus virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): Review of current literature. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020 doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.1273. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33077007; PMCID: PMC7691645. Oct 20:1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Han P., Zhu R. Risk Factors for Viral RNA Shedding in COVID-19 Patients. Eur Respir J. 2020 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01190-2020. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Lau E.H.Y., Wu P. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):672–675. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N., Wang X., Lv T. Prolonged SARS-CoV-2 RNA shedding: Not a rare phenomenon [published onliN.e ahead of print, 2020 Apr 29] J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T.Z., Cao Z.H., Chen Y. Duration of SARS-CoV-2 RNA shedding and factors associated with prolonged viral shedding in patients with COVID-19 [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jul 9] J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.26280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Yan L.-M., Wan L., Xiang T.-X., Le A., Liu J.-M. Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of COVID-19 [Internet] Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30232-2. Apr 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Liu Y., Xu Z., Jiang T., Kang Y., Zhu G., Chen Z. Clinical characteristics and predictors of the duration of SARS-CoV-2 viral shedding in 140 healthcare workers. J Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1111/joim.13160. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32959400. Sep 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh M.D., Park W.B., Choe P.G. Viral load kinetics of MERS coronavirus infection. N England J Med. 2016;375(13):1303–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1511695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi L., Yang Y., Jiang D. Factors associated with the duration of viral shedding in adults with COVID-19 outside of Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;96:531–537. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P., Lim W.S., Emberson J.R. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19 - Preliminary Report. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32678530; PMCID: PMC7383595. Jul 17:NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17023. Published online September 2, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To K.K.-W. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kampen J.J.A., van de Vijver D.A.M.C., Fraaij P.L.A. Duration and key determinants of infectious virus shedding in hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):267. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20568-4. PMID: 33431879; PMCID: PMC7801729. Jan 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Paassen J., Vos J.S., Hoekstra E.M. Corticosteroid use in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis on clinical outcomes. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):696. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03400-9. PMID: 33317589; PMCID: PMC7735177. Dec 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Guo Q., Yan Z. Factors Associated with Prolonged Viral Shedding in Patients With Avian Influenza A(H7N9) Virus Infection. J Infect Dis. 2018;217(11):1708–1717. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K., Zhang X., Sun J. Differences of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Shedding Duration in Sputum and Nasopharyngeal Swab Specimens Aamong Adult Inpatients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 20] Chest. 2020;S0012-3692(20):31718–31719. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2020. Criteria for releasing COVID-19 patients from isolation. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/criteria-for-releasing-covid-19-patients-from-isolation. Last access 06 August 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfel R., Corman V.M., Guggemos W., Seilmaier M., Zange S., Müller M.A. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019 [Internet] Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao A.T., Tong Y.X., Zhang S. Profile of RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2: a preliminary study from 56 COVID-19 patients [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 19] Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa460. ciaa460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K., Chen Y., Yuan J. Factors Associated With Prolonged Viral RNA Shedding in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):799–806. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xudan Chen, Baoyi Zhu, Hong Zeng, Wenxin He Xi, Jingfeng Chen, Haipeng Zheng, Shuang Qiu, Ying Deng, Juliana Chan, Jian Wang. 2020. Associations of clinical characteristics and antiviral drugs with viral RNA clearance in patients with COVID-19 in Guangzhou, China: a retrospective cohort study. 10.1101/2020.04.09.20058941. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz A., Marklund E., Andersson M. Upper respiratory tract levels of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 RNA and duration of viral RNA shedding do not differ between patients with mild and severe/critical Coronavirus disease 2019. J Infect Dis. 2021;223(1):15–18. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa632. PMID: 33020822; PMCID: PMC7665561. Jan 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S., Fan J., Yu F. Viral load dynamics and disease severity in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Zhejiang province, China, January-March 2020: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054e62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. Mar 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B., She J., Wang Y., Ma X. The duration of viral shedding of discharged patients with severe COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa451. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32302000; PMCID: PMC7184358. Apr 17:ciaa451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]