Increasing mobile colistin resistance, mediated by the mcr gene family, in Enterobacteriaceae has become a global concern. Among the 10 reported mcr genes, mcr-8 was first identified in Klebsiella pneumoniae, which could cause severe infections with high mortality. Information about the prevalence and genetic context of mcr-8 is still lacking. In this study, we found that mcr-8 was present in 9.

KEYWORDS: mcr-8, two-component system, colistin resistance, Klebsiella pneumoniae

ABSTRACT

Increasing mobile colistin resistance, mediated by the mcr gene family, in Enterobacteriaceae has become a global concern. Among the 10 reported mcr genes, mcr-8 was first identified in Klebsiella pneumoniae, which could cause severe infections with high mortality. Information about the prevalence and genetic context of mcr-8 is still lacking. In this study, we found that mcr-8 was present in 9.83% of K. pneumoniae isolates of chicken origin. S1 nuclease pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (S1-PFGE) and Southern blotting showed that the mcr-8 gene was located on a plasmid in all of the isolates. The genetic context of the plasmids exhibited considerable diversity from the whole-genome sequence through Illumina and MinION long-read sequencing. Mutations in two-component systems may function synergistically with mcr-8, resulting in extremely high resistance to colistin. In addition to colistin resistance, these plasmids also contained genes conferring resistance to beta-lactams, tetracycline, aminoglycosides, sulfonamides, macrolides, chloramphenicol, and florfenicol. Therefore, these findings indicate that the genetic context of mcr-8 is heterogeneous and diverse and that mcr-8 and certain chromosomal mechanisms jointly contribute to high-level colistin resistance in K. pneumoniae strains, which provides new insights into the resistance mechanisms of K. pneumoniae.

INTRODUCTION

The emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) pathogens poses a significant challenge to public health. Gram-negative pathogens from the so-called ESKAPE group, including Klebsiella pneumoniae, are of particular concern because of their resistance to multiple antimicrobial agents (1). The emergence and rapid dissemination of particular strains of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae have caused an overreliance on last-resort antibiotics, such as colistin (2, 3). In recent years, multiple studies have reported an increasing prevalence of colistin resistance among members of the Enterobacteriaceae family.

Several molecular mechanisms have been associated with colistin resistance in Gram-negative bacteria, such as alterations in PmrA/PmrB and PhoP/PhoQ and alterations in their regulators, the mgrB gene and the crrAB operon (4–6). Mutations leading to the addition of cationic groups to lipid A result in less anionic lipid A and, consequently, less fixation of polymyxins (7). However, the plasmid-mediated mobile colistin resistance (mcr) gene family (mcr-1 to mcr-10), identified in the past 5 years, poses a great threat to public health due to its horizontal transferability, which facilitates rapid dissemination of colistin resistance (8). These genes encoded phosphoethanolamine (pEtN) transferase, which was capable of catalyzing the addition of pEtN to the phosphate group of bacterial lipid A, reducing the negative charge of the outer membrane and thereby attenuating its affinity with positively charged colistin, resulting in drug resistance (8, 9).

K. pneumoniae is an opportunistic pathogen that is identified as an urgent threat to human health, as determined by the World Health Organization (WHO) (10). In particular, carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae isolates have become a major global health concern, because they may cause severe infections with high mortality rates (11). For those serious infections, colistin is regarded as one of the drugs of last resort in human medicine (9). Previously, among all the mcr genes, mcr-1 was the most frequently detected mcr gene among Enterobacteriaceae, especially in Escherichia coli (9, 12, 13). Recent studies have indicated that mcr-8 has also emerged in K. pneumoniae (14–19) as well as other closely related species (K. quasipneumoniae and Raoultella ornithinolytica) (20, 21), which contributes to the horizontal dissemination of colistin resistance among these species. However, information about the molecular genetic context and prevalence of mcr-8 among K. pneumoniae isolates is still lacking. Thus, this study aimed to investigate the prevalence and genetic features of mcr-8 and study its contribution to colistin resistance.

RESULTS

Antimicrobial susceptibility of mcr-8-positive K. pneumoniae.

To describe the presence of mcr genes in K. pneumoniae, PCR amplification was performed in 122 K. pneumoniae strains isolated from 300 chicken cloacae using the primers listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Results showed that 12 (9.83%) isolates contained mcr-8, whereas 6 (4.92%) isolates carried mcr-1. Other mcr genes were not detected. The MICs of colistin and polymyxin B against mcr-8-positive K. pneumoniae ranged from 4 to >128 μg/ml. It is worth noting that the MICs of KP4, KP49, KP700, and KP744 isolates to colistin exceeded 32 μg/ml, suggesting that these isolates contain other colistin resistance mechanisms in addition to mcr-8. All mcr-8-positive strains were resistant to tetracycline, gentamicin, florfenicol, and ciprofloxacin but were susceptible to meropenem (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

MICs of tested antimicrobial agents for the studied bacterial isolatesa

| Designation | MIC (μg/ml) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CST | PB | TET | MEM | TAZ | GEN | STR | FFC | CIP | |

| KP22 | 16 | 8 | 128 | 0.03 | 0.5 | >512 | >512 | 256 | 64 |

| JKP22 | 4 | 4 | 32 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 256 | 256 | 256 | 0.016 |

| KP688 | 16 | 4 | >256 | 0.03 | 8 | >512 | >512 | 256 | 64 |

| JKP688 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 512 | 4 | 4 | 0.008 |

| KP8 | 8 | 4 | >256 | 0.03 | 8 | >512 | >512 | 256 | 64 |

| JKP8 | 2 | 1 | <0.25 | 0.03 | <0.06 | 0.5 | 2 | 4 | 0.008 |

| KP12 | 16 | 8 | >256 | 0.03 | 16 | >512 | >512 | >256 | >128 |

| JKP12 | 4 | 2 | 64 | 0.03 | 0.125 | 256 | 1 | 2 | 0.008 |

| KP70 | 16 | 16 | 128 | 0.06 | 16 | >512 | >512 | 256 | 128 |

| JKP70 | 8 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.03 | 0.125 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 0.008 |

| KP744 | 32 | 32 | 64 | 0.06 | 16 | >512 | >512 | >256 | >128 |

| JKP744 | 1 | 0.5 | <0.25 | 0.03 | 2 | >512 | 256 | 4 | 0.004 |

| KP69 | 8 | 8 | >256 | 0.06 | 16 | >512 | >512 | 256 | 64 |

| JKP69 | 4 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0.25 |

| KP700 | >128 | >128 | >256 | 0.03 | 8 | >512 | 512 | >256 | >128 |

| JKP700 | 1 | 0.5 | <0.25 | 0.03 | 8 | 256 | 256 | 4 | 0.004 |

| KP3 | 8 | 4 | >256 | 0.125 | 32 | >512 | >512 | 256 | 128 |

| JKP3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.5 | 8 | 4 | 0.25 |

| KP4 | 64 | 64 | 128 | 0.06 | 32 | >512 | >512 | >256 | >128 |

| JKP4 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 8 | 4 | 0.06 |

| KP32 | 4 | 4 | >256 | 0.06 | 32 | >512 | 64 | >256 | >128 |

| JKP32 | 4 | 2 | <0.25 | 0.03 | 4 | <0.125 | <0.25 | 128 | 0.004 |

| KP49 | >128 | >128 | >256 | 0.125 | 32 | >512 | 64 | >256 | >128 |

| JKP49 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.03 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 0.004 |

| J53 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.5 | <0.125 | 4 | 4 | 0.015 |

| CKP8 | 2 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CKP744 | 16 | 16 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| CKP4 | 16 | 16 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

Antimicrobial susceptibilities were interpreted as resistant (boldface) or susceptible (plain text) in accordance with established breakpoints. CST, colistin; PB, polymyxin B; TET, tetracycline; MEM, meropenem; TAZ, ceftazidime; GEN, gentamicin; STR, streptomycin; FFC, florfenicol; CIP, ciprofloxacin. A dash indicates that the MIC was not measured. JKP22 was the transconjugant of K. pneumoniae KP22, and other strains are the same. CKP8, CKP744, and CKP4 were the plasmid-cured strains of KP8, KP744, and KP4, respectively.

mcr-8 was located on various conjugative plasmids.

To define the location and transferability of mcr-8, S1 nuclease pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (S1-PFGE), Southern blotting, and conjugation assays were carried out. Southern blotting indicated that all mcr-8 genes were located on plasmids, with sizes ranging from 60 to 250 kb (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), in these K. pneumoniae strains. The conjugation assay showed that all the mcr-8 containing plasmids were transferable from K. pneumoniae isolates to the E. coli J53 recipient strain at frequencies ranging from 10−6 to 10−8, and it resulted in a 2- to 32-fold increase in the resistance to colistin in all transconjugants (Table 1).

Genetic environment of mcr-8 in K. pneumoniae.

To characterize the genetic environment of mcr-8, the genomes of 12 mcr-8-containing K. pneumoniae strains were sequenced. At least 100× coverage of raw reads from Illumina sequencing was obtained for each isolate. The number of contigs ranged from 55 to 297, while the N50 of contigs ranged from 41 to 562 kb for the isolates assembled by the CLC Genomics Workbench (version 8.5). To obtain the complete sequence of the mcr-8-containing plasmids, these isolates were resequenced by MinION long-read sequencing. The draft genomes of these isolates were 5,700 to ∼6,300 kb in length, with a GC content of 56.10 to ∼56.92%. The mcr-8-carrying plasmids were 83.67 to ∼251.13 kb in length, with a GC content of 50.13 to ∼52.83%. Analysis of plasmid replicons indicated that all of them were IncF-type plasmids, except pKP22, which was a large hybrid plasmid containing IncA and IncC composition replicons. These plasmids belong to three Inc types: IncFIA related (n = 7), IncA/C related (n = 1), and IncFIIK related (n = 4) (Fig. 1). Generally, mcr-8 was found in seven plasmids of different sizes (Fig. 2), specifically, pKP722 (n = 1), pKP12 (n = 2), pKP4 (n = 1), pKP3 (n = 4), pKP744 (n = 2), pKP49 (n = 1), and pKP700 (n = 1), with a length of 251.13 kb, 122.03 kb, 111.36 kb, 95.19 kb, 98.36 kb, 83.67 kb, and 83.45 kb, respectively (Fig. 2).

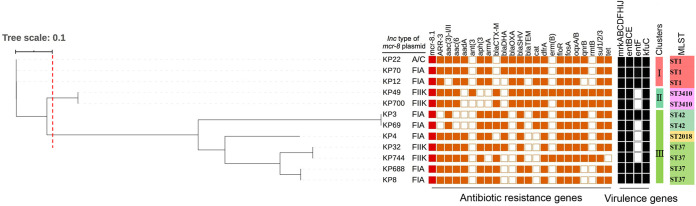

FIG 1.

Phylogenetic tree and distribution of mcr-8-positive K. pneumoniae phylogroups, Inc-type plasmid, antimicrobial resistance genes, virulence-associated genes, cluster groups, and multilocus sequencing types. The phylogenetic tree was generated based on K. pneumoniae strain KP70 as a reference.

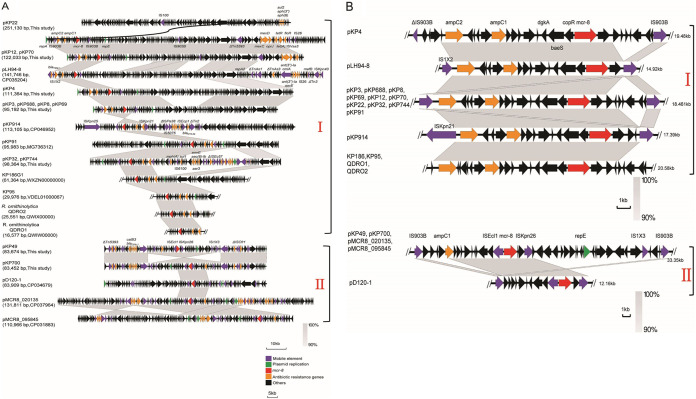

FIG 2.

Genetic organization of plasmid harboring mcr-8.1. (A) Comparison of the complement sequence of the mcr-8 plasmid found in this study with previously reported pLH94-8 (GenBank accession no. CP035204), pKP91 (MG736312), pKP914 (CP046952), KP186G1 (WXZN00000000), KP95 (VDEL01000067), R. ornithinolytica QDRO2 (QWIW00000000), R. ornithinolytica QDRO1 (QWIX00000000), pD120-1 (CP034679), pMCR8_020135 (CP037964), and pMCR8_095845 (CP031883). (B) Schematic representation and comparison of the genetic environment of the mcr-8-flanking region in each genomic backbone type. Arrows indicate the direction of transcription of each gene, and different genes are shown in different colors. Regions of ≥90.0% nucleotide sequence identity are shaded gray.

Analysis of the genetic environment showed that mcr-8.1 genes in pKP22, pKP12, pKP4, pKP3, and pKP744 were similar and were composed of IS903B-orf-mcr-8.1-orf-IS903B (Fig. 2), which was similar to that of the mcr-8.1 gene in plasmid pK91 that we reported previously (14) but slightly different from reports by Farzana et al. (16) and Hadjadj et al. (17) that the right IS903B was replaced by ISKpn21. However, the genetic context of the mcr-8.1 gene in pKP49 and pKP700 was ISEcl1-mcr-8.1-orf-ISKpn26 (Fig. 2), which was distinct from the others. In addition, mcr-8.1-carrying plasmids also contained genes conferring resistance to beta-lactams, tetracycline, aminoglycosides, sulfonamides, macrolides, chloramphenicol, and florfenicol. Additionally, all plasmids shown in Fig. 2 could be divided into two groups (I and II) according to sequence homology. A fragment of 11.6 kb surrounding mcr-8.1 in group I was identical to that described from the K. pneumoniae plasmids pKP91 (GenBank accession no. MG736312), pLH94-8 (CP035204), pKP914 (CP046952), KP186 (WXZN00000000), and KP95 (VDEL01000067) and two R. ornithinolytica fragments (QWIW00000000 and QWIX00000000) (Fig. 2), whereas an 11.0-kb nucleotide sequence existed in all group II plasmids (Fig. 2). Moreover, we also found that both plasmids in groups I and II shared two genes coding for the response regulator transcription factor, CopR, and HAMP domain-containing histidine kinase BaeS, which constitutes a two-component system involved in colistin resistance in Enterobacteriaceae, a phenomenon that was also observed by Hadjadj et al. (17). However, whether this putative two-component system is associated with mcr-8-mediated colistin resistance needs to be further demonstrated.

Molecular genetic characteristics of the mcr-8-carrying strains.

To investigate the molecular characteristics of these mcr-8-carrying strains, multilocus sequence typing (MLST), Bayesian type, phylogenetic typing, resistance genes, and virulence genes were analyzed. Results showed that these isolates belonged to 5 different sequence types (ST; ST1, ST3410, ST42, ST2018, and ST37). Bayesian analysis of the population structure revealed four distinct lineages among the 12 K. pneumoniae isolates. The major lineage, lineage I, included 5 isolates belonging to ST1 and ST3410, suggesting that clonal dissemination emerged in mcr-8-carrying K. pneumoniae strains. A phylogenetic tree was obtained based on core genome single-nucleotide polymorphism (cgSNP) using Harvest version 1.1.2. Using a cutoff of 0.1 in tree-scale pattern similarity, the 12 K. pneumoniae isolates were grouped into 3 clusters (Fig. 1). The first cluster included KP22, KP70, and KP12, and they exhibited high genetic similarity (≤42 SNPs; Table S2), consistent with ST1. KP49 and KP700, belonging to the second cluster, shared the same type, ST3410. The third cluster included KP3, KP69, KP4, KP32, KP744, KP688, and KP8, among which KP3 and KP69 shared the same type of ST42, KP4 exhibited ST2018, and KP32, KP744, KP688, and KP8 shared ST37.

Antibiotic resistance genes carried by the K. pneumoniae isolates were identified from whole-genome sequence (WGS) data. In addition to mcr-8, several other important resistance genes were identified in all the K. pneumoniae isolates, including beta-lactam genes blaSHV-119 and blaSHV-182, trimethoprim resistance gene dfrA12-dfrA17-dfrA27, florfenicol resistance gene floR, fosfomycin resistance gene fosA, quinolone resistance gene oqxA-oqxB, and sulfonamide resistance gene sul1-sul2-sul3. Overall, molecular genetic analysis suggested that the mcr-8-positive K. pneumoniae isolates were also genetically diverse and that mcr-8 could disseminate among different K. pneumoniae isolates, mainly by horizontal transmission.

The presence of other mechanisms contributing to colistin resistance.

To determine if K. pneumoniae contains other mechanisms contributing to colistin resistance in addition to mcr-8, we eliminated the mcr-8 gene through plasmid curing. The mcr-8-carrying plasmids were successfully cured from KP8, KP744, and KP4, whose MICs to colistin were 8, 32, and 64 μg/ml, respectively. The corresponding plasmid-cured isolates were named CKP8, CKP744, and CKP4, respectively, and confirmed by PCR and S1-PFGE (Fig. S2). The loss of mcr-8-carrying plasmid restored susceptibility to colistin in CKP8, whereas CKP744 and CKP4 remained resistant to colistin at a MIC of 16 μg/ml, despite a decrease of 2- to 4-fold in resistance compared with their wild-type isolates (Table 1). These results indicated the presence of other mechanisms that might function synergistically with mcr-8 in mediating high-level resistance to colistin in K. pneumoniae isolates.

Mutations in two-component systems.

To identify whether mutations occurred in the two-component systems in CKP744 and CKP4 strains, we analyzed the sequences of MgrB, PhoP/Q, PmrAB, and CrrAB of these two strains. The results showed that CKP4 contained a Q22P substitution in MgrB as well as additional amino acid mutations in PhoQ (T246A and R256G) and CrrB (I27V, D189E, and V237I). Moreover, CKP744 had an amino acid substitution (D29V) in MgrB and several amino acid mutations in PmrB (R256G) and CrrB (I27V, D189E, V237I, F303S, and V323L). These mutations might contribute to colistin resistance in K. pneumoniae isolates.

Virulence of mcr-8-carrying isolates.

To identify the virulence factors associated with the mcr-8-positive K. pneumoniae isolates, whole-genome sequences were compared with the database of virulence factors that were publicly available. There are three groups of virulence factors found in these 12 mcr-8-positive K. pneumoniae isolates, including gene clusters associated with the type Ш fimbrial operon mrkABCDJHKI, siderophore system enterobactin entBCE, and Klebsiella ferrous iron uptake system gene kfuC.

DISCUSSION

In this study, 12 mcr-8-positive K. pneumoniae isolates from chicken anal swab samples were analyzed by a combination of Illumina and MinION long-read sequencing. We observed significant diversity in the genetic context of mcr-8 as well as the host K. pneumoniae. The first description of the mcr-8 gene located it on a conjugative IncFII-type plasmid in K. pneumoniae isolated from animals and humans in 2018 (14). To date, the mcr-8 gene and its variants have been described in K. pneumoniae, Raoultella ornithinolytica, and K. quasipneumoniae from human, animal, and environmental origins. Among them, K. pneumoniae is the main host of the mcr-8 gene in both animals and humans (14, 16, 20, 21). Here, we detected 12 out of 122 K. pneumoniae isolates containing mcr-8 and showed that mcr-8 was located on plasmids of different sizes (Fig. 2) and that its genetic environment is complex and diverse, which suggests that mcr-8 has been widely disseminated.

To date, three mcr-8 variants (mcr-8.1 to mcr-8.3) have been identified in K. pneumoniae isolates belonging to ST42, ST336, ST967, ST15, and ST1 (mcr-8.1), ST11 (mcr-8.2), and ST39 (mcr-8.3) (21). In this study, mcr-8-positive K. pneumoniae belonged to 5 different types, including ST1, ST3410, ST42, ST2018, and ST37. Among them, K. pneumoniae ST37 is widely distributed in companion animals and neonatal and environmental scenarios, and hypervirulent K. pneumoniae ST37 from patient stool samples can cause liver abscess (22–24). In this study, we found that mcr-8 can emerge in ST1 K. pneumoniae from chicken, and mcr-8 has been identified in an ST1 clinical carbapenem- and colistin-resistant K. pneumoniae strain by Ma et al. (18), indicating the potential transmission of mcr-8-carrying strains between humans and animals. In this study, we also found that mcr-8 emerged in ST42 K. pneumoniae strains, which have been reported in pigs (14). The presence of mcr-8.2 has been reported in K. quasipneumoniae in swine (20) and panresistant K. pneumoniae with ST11 in human patients (25). The presence of mcr-8.3 has been identified in Klebsiella pneumoniae and in two other closely related species, Klebsiella quasipneumoniae and Raoultella ornithinolytica (21).

Additionally, we identified a conservative region around mcr-8, flanked by IS903B, that was identical to the first mcr-8 plasmid in KP91 (14), facilitating the cotransfer of mcr-8 and aminoglycoside-resistant genes. In subclade II (Fig. 2), ISEcl1 and ISKpn26 were located adjacent to mcr-8, which was similar to p18-29 mcr-8.2 (GenBank accession no. MK262711.1) from colistin- and carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae carrying blaNDM-1 and mcr-8.2 (25). Previous reports showed that mcr-8 was located on IncQ, IncR, IncFII, IncFIA, and IncFIB replicon plasmids (16, 18, 25). In our study, IncFIIK and IncFIA replicons were found, and IncA/C replicons were also the first found to carry mcr-8. This suggests that the molecular genetic features of mcr-8 are diverse, possibly due to evolutionary development in chicken cecum; therefore, surveillance of this gene is urgently needed.

Consistent with previous reports (14, 16, 20), all of the mcr-8-positive K. pneumoniae isolates in the present study were resistant to colistin, and the MIC of colistin of recipient strains immediately increased after plasmid transfer. Additionally, even after plasmid curing, two K. pneumoniae strains remained resistant to colistin. On the other hand, mutations in the two-component systems PhoP/Q, PmrAB, and/or their regulators (MgrB and CrrAB operon) were identified in these K. pneumoniae strains through WGS analysis, which is well known as another colistin resistance mechanism in K. pneumoniae (26). This evidence indicates that mcr-8 exerts synergistic effects together with the chromosomal mechanism in mediating colistin resistance in some K. pneumoniae isolates.

In conclusion, we found 12 mcr-8-positive K. pneumoniae isolates from chicken, and mcr-8 was located on various conjugative plasmids. The plasmids were classified into three Inc types (IncFIA [n = 7], IncA/C [n = 1], and IncFIIK [n = 4]); IncFIA was the most prevalent type among these isolates. Interestingly, the genetic contexts of mcr-8 were found to be highly divergent, yet the mcr-8 genes were adjacent to insertion sequence (IS) elements (Fig. 2). IS903B was the most common IS element and was found to be adjacent to mcr-8 at one end or both ends. Furthermore, whether IS903B could form a circular intermediate and contribute to the mobilization of mcr-8 remains unknown, but the presence of IS elements would enhance the transmission of mcr-8 and facilitate its close association with other antibiotic resistance genes. The mcr-8 gene may exert synergistic effects together with chromosomal mutations in mediating colistin resistance in K. pneumoniae isolates, suggesting that heterogeneous colistin resistance mechanisms are emerging. Therefore, close surveillance is urgently needed to monitor the prevalence of mcr-8 genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolation and identification.

A total of 300 chicken anal swab samples (100 samples per farm) were collected from 3 commercial poultry farms at one time in Shandong Province, China, in 2017, and these samples were derived from individual animals. All K. pneumoniae isolates were recovered on CHROMagar orientation plates with 2 mg/liter colistin and identified by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (Bruker Daltonik, Bremen, Germany) and 16S rRNA gene sequencing. The presence of mcr genes (mcr-1 to mcr-10) was confirmed by PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing, as previously described (14).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

The MICs of the K. pneumoniae isolates and their transconjugants were determined using the broth microdilution method and interpreted according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (document VET01-A4) and European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) (http://www.eucast.org). E. coli ATCC 25922 was used as a quality control strain. Nine antibiotics were tested at a series of concentrations, and the maximum concentrations used were 512 μg/ml for gentamicin and streptomycin, 256 μg/ml for tetracycline and florfenicol, 128 μg/ml for colistin, polymyxin B, and ciprofloxacin, and 64 μg/ml for ceftazidime and meropenem. All of the microtiter plates were made by us.

Conjugation assay.

Conjugation assays were performed according to a previously described method (27). Donor strains (mcr-8-positive K. pneumoniae) were diluted to the 0.5 McFarland standard and mixed with azide-resistant E. coli J53 as the recipient at a donor/recipient ratio of 1:3 on microporous membrane at 37°C for 12 h. The mixtures were collected and plated on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar containing azide (100 μg/ml) and colistin (1 μg/ml). The transfer frequency was calculated as the number of transconjugants per recipient (28).

PFGE, S1-PFGE, and Southern blotting.

The mcr-8-positive K. pneumoniae isolates were subjected to PFGE using XbaI as a restriction endonuclease based on a published method (29). XbaI-restricted DNA of Salmonella enterica serovar Braenderup H9812 was used as a DNA marker. PFGE patterns were analyzed using InfoQuest software version 4.5 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). S1 nuclease-PFGE and Southern blotting were performed to locate mcr-8 and determine plasmid size in K. pneumoniae as previously described (30, 31). In brief, strains were embedded in agarose gel plugs and digested with S1 nuclease (TaKaRa, Japan). After PFGE, specific mcr-8 probes were used for gene localization by Southern blotting using the DIG High Prime DNA labeling and detection starter kit II (Roche Diagnostics).

Plasmid curing.

The plasmid-curing assay was performed as previously described (32). Strains were subcultured every 18 h (42°C, 200 rpm) in LB broth containing 10 μg/ml ethidium bromide (EB) or novobiocin. After each subculture, the strains were diluted 10 times in LB broth and plated on drug-free LB agar at 37°C overnight. The emerging colonies were duplicated onto LB agar plates in the presence or absence of colistin at half the MIC of each test strain. Colonies that failed to grow on the colistin plates were considered plasmid eliminated, and their duplicates on drug-free plates were selected for PCR and S1-PFGE verification.

Genome sequencing and analysis.

Whole-genome DNA was extracted using the Wizard genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, Beijing, China) and subjected to 150-bp paired-end whole-genome sequencing using the Illumina HiSeq 2500 System (Annoroad, Beijing, China), along with MinION (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Inc., United Kingdom). CLC Genomics Workbench 9.0 (CLC Bio-Qiagen, Aarhus, Denmark) was used to assemble short reads from Illumina and long reads by Nanopore. The ST of K. pneumoniae was determined in silico by MLST analysis using the published database (33). Plasmid replicon type analysis was carried out at the Center for Genomic Epidemiology (34). Antibiotic resistance genes were detected based on the ARG-ANNOT database (35). The genetic environment of mcr-8 was determined by comparing the sequences surrounding mcr-8 in K. pneumoniae isolates in this study and from the NCBI database. The presence of mutations in the mgrB, pmrA, pmrB, phoP, phoQ, crrA, and crrB genes was investigated using amino acid alignments. Phylogenetic trees based on the whole-genome sequences of K. pneumoniae isolates were structured using Harvest version 1.1.2 (36), combined with the corresponding characteristics of each isolate using the online tool iTOL, version 3 (37).

Data availability.

Whole-genome sequences of the studied strains have been deposited in the NCBI database (BioProject accession no. PRJNA649714 and BioSample accession no. SAMN15698029 to SAMN15698040).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31722057, 31761133004, and 31672604), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (SBK2020042767), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2020M671526). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wand ME, Bock LJ, Bonney LC, Sutton JM. 2017. Mechanisms of increased resistance to chlorhexidine and cross-resistance to colistin following exposure of Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates to chlorhexidine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e01162-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01162-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yigit H, Queenan AM, Anderson GJ, Domenech-Sanchez A, Biddle JW, Steward CD, Alberti S, Bush K, Tenover FC. 2001. Novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase, KPC-1, from a carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:1151–1161. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1151-1161.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nordmann P. 2014. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: overview of a major public health challenge. Med Mal Infect 44:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cannatelli A, D'Andrea MM, Giani T, Di Pilato V, Arena F, Ambretti S, Gaibani P, Rossolini GM. 2013. In vivo emergence of colistin resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae producing KPC-type carbapenemases mediated by insertional inactivation of the PhoQ/PhoP mgrB regulator. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:5521–5526. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01480-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cannatelli A, Di Pilato V, Giani T, Arena F, Ambretti S, Gaibani P, D'Andrea MM, Rossolini GM. 2014. In vivo evolution to colistin resistance by PmrB sensor kinase mutation in KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae is associated with low-dosage colistin treatment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:4399–4403. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02555-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng HY, Chen YF, Peng HL. 2010. Molecular characterization of the PhoPQ-PmrD-PmrAB mediated pathway regulating polymyxin B resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae CG43. J Biomed Sci 17:60. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-17-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olaitan AO, Morand S, Rolain JM. 2014. Mechanisms of polymyxin resistance: acquired and intrinsic resistance in bacteria. Front Microbiol 5:643. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang C, Feng Y, Liu L, Wei L, Kang M, Zong Z. 2020. Identification of novel mobile colistin resistance gene mcr-10. Emerg Microbes Infect 9:508–516. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1732231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y-Y, Wang Y, Walsh TR, Yi L-X, Zhang R, Spencer J, Doi Y, Tian G, Dong B, Huang X, Yu L-F, Gu D, Ren H, Chen X, Lv L, He D, Zhou H, Liang Z, Liu J-H, Shen J. 2016. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis 16:161–168. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin RM, Bachman MA. 2018. Colonization, infection, and the accessory genome of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 8:4. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munoz-Price LS, Poirel L, Bonomo RA, Schwaber MJ, Daikos GL, Cormican M, Cornaglia G, Garau J, Gniadkowski M, Hayden MK, Kumarasamy K, Livermore DM, Maya JJ, Nordmann P, Patel JB, Paterson DL, Pitout J, Villegas MV, Wang H, Woodford N, Quinn JP. 2013. Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. Lancet Infect Dis 13:785–796. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70190-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Tian G-B, Zhang R, Shen Y, Tyrrell JM, Huang X, Zhou H, Lei L, Li H-Y, Doi Y, Fang Y, Ren H, Zhong L-L, Shen Z, Zeng K-J, Wang S, Liu J-H, Wu C, Walsh TR, Shen J. 2017. Prevalence, risk factors, outcomes, and molecular epidemiology of mcr-1-positive Enterobacteriaceae in patients and healthy adults from China: an epidemiological and clinical study. Lancet Infect Dis 17:390–399. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30527-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwarz S, Johnson AP. 2016. Transferable resistance to colistin: a new but old threat. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:2066–2070. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, Wang Y, Zhou Y, Li J, Yin W, Wang S, Zhang S, Shen J, Shen Z, Wang Y. 2018. Emergence of a novel mobile colistin resistance gene, mcr-8, in NDM-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Emerg Microbes Infect 7:122. doi: 10.1038/s41426-018-0124-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonnin RA, Bernabeu S, Jaureguy F, Naas T, Dortet L. 2020. MCR-8 mediated colistin resistance in a carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from a repatriated patient from Morocco. Int J Antimicrob Agents 55:105920. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farzana R, Jones LS, Barratt A, Rahman MA, Sands K, Portal E, Boostrom I, Espina L, Pervin M, Uddin A, Walsh TR. 2020. Emergence of mobile colistin resistance (mcr-8) in a highly successful Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 15 clone from clinical infections in Bangladesh. mSphere 5:e00023-20. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00023-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hadjadj L, Baron SA, Olaitan AO, Morand S, Rolain JM. 2019. Co-occurrence of variants of mcr-3 and mcr-8 genes in a Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate from Laos. Front Microbiol 10:2720. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma K, Feng Y, Liu L, Yao Z, Zong Z. 2020. A cluster of colistin- and carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae carrying blaNDM-1 and mcr-8.2. J Infect Dis 221:S237–S242. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nabti LZ, Sahli F, Ngaiganam EP, Radji N, Mezaghcha W, Lupande-Mwenebitu D, Baron SA, Rolain JM, Diene SM. 2020. Development of real-time PCR assay allowed describing the first clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate harboring plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mcr-8 gene in Algeria. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 20:266–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2019.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang X, Liu L, Wang Z, Bai L, Li R. 2019. Emergence of mcr-8.2-bearing Klebsiella quasipneumoniae of animal origin. J Antimicrob Chemother 74:2814–2817. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang X, Wang Y, Zhou Y, Wang Z, Wang Y, Zhang S, Shen Z. 2019. Emergence of colistin resistance gene mcr-8 and its variant in Raoultella ornithinolytica. Front Microbiol 10:228. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xia J, Fang LX, Cheng K, Xu GH, Wang XR, Liao XP, Liu YH, Sun J. 2017. Clonal spread of 16S rRNA methyltransferase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST37 with high prevalence of ESBLs from companion animals in China. Front Microbiol 8:529. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu J, Sun L, Ding B, Yang Y, Xu X, Liu W, Zhu D, Yang F, Zhang H, Hu F. 2016. Outbreak of NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST76 and ST37 isolates in neonates. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 35:611–618. doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2578-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim JH, Jeong Y, Lee CK, Kim SB, Yoon YK, Sohn JW, Kim MJ. 2020. Characteristics of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from stool samples of patients with liver abscess caused by hypervirulent K. pneumoniae. J Korean Med Sci 35:e18. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qin S, Zhang C, Schwarz S, Li L, Dong H, Yao H, Du XD. 2020. Identification of a novel conjugative mcr-8.2-bearing plasmid in an almost pan-resistant hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae ST11 isolate with enhanced virulence. J Antimicrob Chemother 75:2696–2699. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poirel L, Jayol A, Nordmann P. 2017. Polymyxins: antibacterial activity, susceptibility testing, and resistance mechanisms encoded by plasmids or chromosomes. Clin Microbiol Rev 30:557–596. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00064-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, Zhang R, Li J, Wu Z, Yin W, Schwarz S, Tyrrell JM, Zheng Y, Wang S, Shen Z, Liu Z, Liu J, Lei L, Li M, Zhang Q, Wu C, Zhang Q, Wu Y, Walsh TR, Shen J. 2017. Comprehensive resistome analysis reveals the prevalence of NDM and MCR-1 in Chinese poultry production. Nat Microbiol 2:16260. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yin W, Li H, Shen YB, Liu ZH, Wang SL, Shen ZQ, Zhang R, Walsh TR, Shen JZ, Wang Y. 2017. Novel plasmid-mediated colistin resistance gene mcr-3 in Escherichia coli. mBio 8:e00543-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01166-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han H, Zhou H, Li H, Gao Y, Lu Z, Hu K, Xu B. 2013. Optimization of pulse-field gel electrophoresis for subtyping of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int J Environ Res Public Health 10:2720–2731. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10072720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barton BM, Harding GP, Zuccarelli AJ. 1995. A general method for detecting and sizing large plasmids. Anal Biochem 226:235–240. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng B, Huang C, Xu H, Guo L, Zhang J, Wang X, Jiang X, Yu X, Jin L, Li X, Feng Y, Xiao Y, Li L. 2017. Occurrence and genomic characterization of ESBL-producing, mcr-1-harboring Escherichia coli in farming soil. Front Microbiol 8:2510. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karthikeyan V, Santosh SW. 2010. Comparing the efficacy of plasmid curing agents in Lactobacillus acidophilus. Benef Microbes 1:155–158. doi: 10.3920/BM2009.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larsen MV, Cosentino S, Rasmussen S, Friis C, Hasman H, Marvig RL, Jelsbak L, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Ussery DW, Aarestrup FM, Lund O. 2012. Multilocus sequence typing of total-genome-sequenced bacteria. J Clin Microbiol 50:1355–1361. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06094-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nithya N, Remitha R, Jayasree PR, Faisal M, Manish KP. 2017. Analysis of beta-lactamases, blaNDM-1 phylogeny & plasmid replicons in multidrug-resistant Klebsiella spp. from a tertiary care centre in south India. Indian J Med Res 146:S38–S45. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_31_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gupta SK, Padmanabhan BR, Diene SM, Lopez-Rojas R, Kempf M, Landraud L, Rolain JM. 2014. ARG-ANNOT, a new bioinformatic tool to discover antibiotic resistance genes in bacterial genomes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:212–220. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01310-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Treangen TJ, Ondov BD, Koren S, Phillippy AM. 2014. The Harvest suite for rapid core-genome alignment and visualization of thousands of intraspecific microbial genomes. Genome Biol 15:524. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0524-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Letunic I, Bork P. 2016. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res 44:W242–W245. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Whole-genome sequences of the studied strains have been deposited in the NCBI database (BioProject accession no. PRJNA649714 and BioSample accession no. SAMN15698029 to SAMN15698040).