Abstract

The expanded microbiological evaluation of a series of rifastures, novel spiropiperidyl rifamycin derivatives, against clinically relevant ESKAPE bacteria has identified several analogs with promising in vitro bioactivities against antibiotic-resistant strains of Enterococcus faecium and Staphylococcus aureus. Thirteen of the rifastures displayed minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) below 1 μg/ml against the methicillin- and vancomycin-resistant forms of S. aureus and E. faecium (MRSA, VRSA, VRE). Aryl-substituted rifastures 1, 11, and 12 offered the greatest bioactivity, with MICs reaching ≤0.063 μg ml−1 for these human pathogens. Further analysis indicates that diphenyl rifasture 1 had greater antibiofilm activity against S. aureus and lower cytotoxicity in mammalian HEK cells than rifabutin.

Introduction

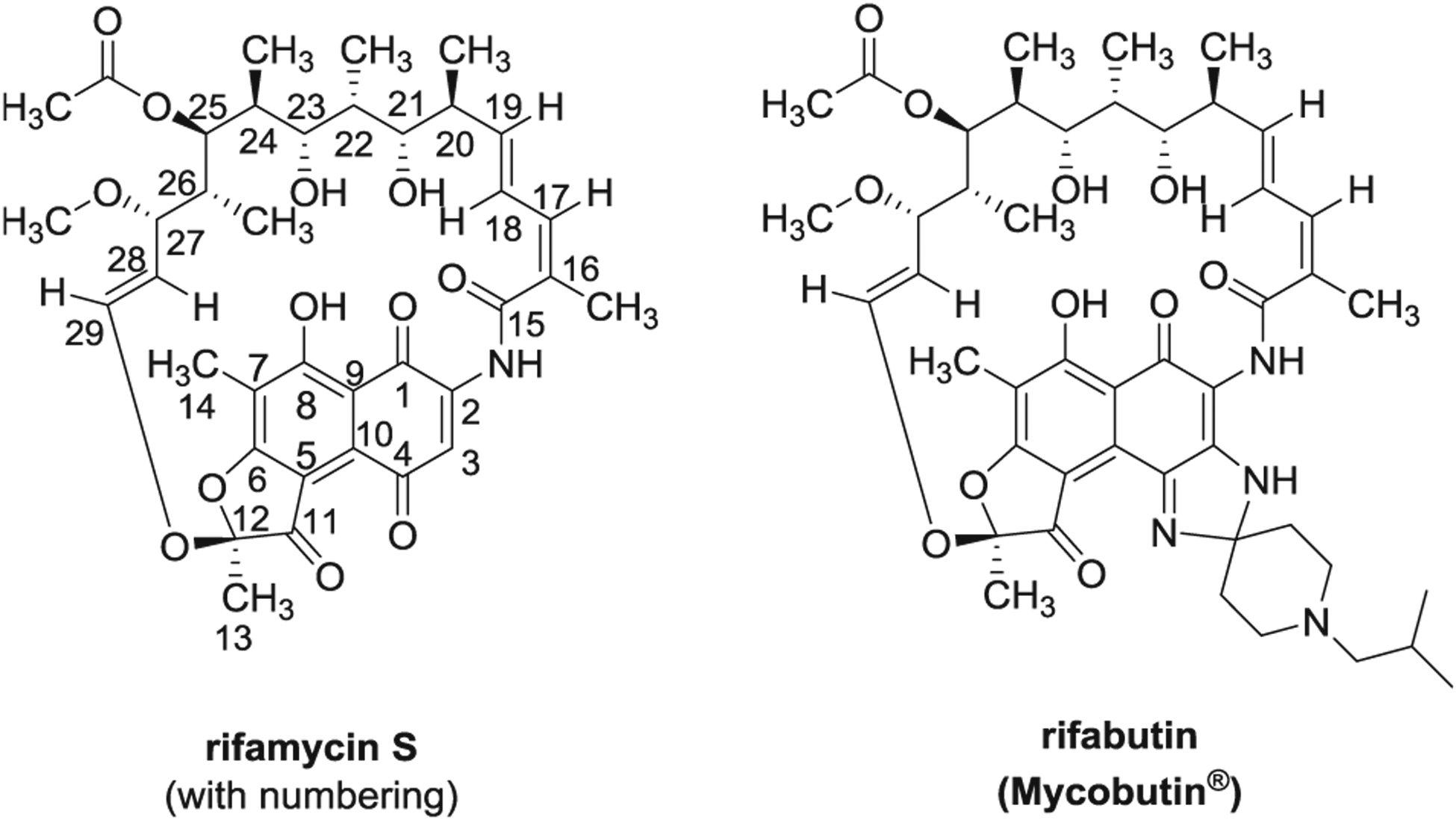

The rifamycins are a family of naphthalenic ansamycin antibiotics that have been used clinically for the treatment of tuberculosis and other infections of bacterial origin [1–4]. The first rifamycins were isolated in 1959 from Amycolatopsis mediterranei as a mixture of at least five microbially active metabolites, designated rifamycins A–E. Rifamycin B was isolated as a pure crystalline compound, which in oxygenated aqueous solutions converts into the more highly bioactive product, rifamycin S (Fig. 1). Structurally, rifamycin S has a 17-membered aliphatic bridge connecting nonadjacent positions on a chromophoric naphthahy-droquinone nucleus via an amide linkage [5, 6].

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of rifamycin S and rifabutin

The rifamycins are generally active against a variety of Gram-positive bacteria and mycobacteria, most notably Mycobacterium tuberculosis [7, 8]. Their antibacterial properties stem from their potent inhibition of bacterial DNA-dependent RNA polymerases, by formation of a stabilized complex with the polymerase proteins within the β subunit and leads to disruption of bacterial RNA synthesis [9–11]. Most rifamycins are ineffective toward binding to the mammalian RNA polymerase; therefore, they display low toxicity toward human cell lines.

Structure antibacterial activity studies on the rifamycins indicate that oxygenated groups must be present at the C-1, C-8, C-21, and C-23 positions and thought to be directly involved in the attachment to the polymerase enzyme [12]. Indeed, modifications at C-3 and/or C-4 positions, which are on the opposite side of the aromatic ring, have been mostly exploited for the preparation of new active derivatives including spiropiperidyl analogs (e.g., rifabutin, Fig. 1). These structural changes do not alter the antibiotic mode of action, but enhance activity by improving membrane permeability and pharmacokinetic properties [13].

Recent investigations at the University of Oviedo, Spain have uncovered a unique series of spiroketal rifamycin derivatives called rifastures with potent activity against drug-resistant strains of clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis [14]. These compounds were prepared by the condensation of 3-amino-4-iminorifamycin S with several types of substituted 4-piperidones (Fig. 2, Table 1) [15]. The major (M) and minor (m) diastereomers were separated by preparative TLC and evaluated individually. Phenyl-substituted rifastures exhibited the highest level of growth inhibition with MICs reaching 1 and 0.02 μg ml−1 against rifampin- and isoniazid-resistant M. tuberculosis strains, respectively [15]. The structures of the rifastures were further investigated by nuclear magnetic resonance [16] and molecular dynamic studies suggest that the compounds may induce tighter binding to RNA polymerase in M. tuberculosis mutants that have developed resistance to the rifamycins [17]. The potential effects of these compounds on other microbes or human cells remained unknown, and are the subject of this current study.

Fig. 2.

Spiropiperidyl rifastures (RFA) were synthesized by condensation of 3-amino-4-iminorifamycin S with substituted 4-piperidones [15]

Table 1.

Comparisons of minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of rifastures to antibiotic standards

| Compound | Ar | R | Species|MIC (μg ml−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRSA COL | VRSA HIP14300 | VRE HF50104 | |||

| RFA-1M | Ph | –CH2CH=CH2 | 0.125 | ≤0.063 | 1 |

| RFA-1m | Ph | –CH2CH=CH2 | ≤0.063 | ≤0.063 | 0.25 |

| RFA-2M | 2-BrPh | –CH2CH=CH2 | 8 | 8 | 32 |

| RFA-3M | 3-BrPh | –CH2CH=CH2 | 0.25 | 2 | 16 |

| RFA-3m | 3-BrPh | –CH2CH=CH2 | 4 | 8 | 64 |

| RFA-4M | 2-IPh | –CH2CH=CH2 | 4 | 8 | 32 |

| RFA-4m | 2-IPh | –CH2CH=CH2 | 2 | 2 | 32 |

| RFA-5M | 4-MeOPh | –CH2CH=CH2 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| RFA-5m | 4-MeOPh | –CH2CH=CH2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| RFA-6M | 3,4-diMeOPh | –CH2CH=CH2 | 8 | 8 | 32 |

| RFA-6m | 3,4-diMeOPh | –CH2CH=CH2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2 |

| RFA-7M | 4-FPh | –CH2CH=CH2 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 2 |

| RFA-7m | 4-FPh | –CH2CH=CH2 | 4 | 8 | 16 |

| RFA-8m | 4-ClPh | –CH2CH=CH2 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| RFA-9M | Ph | –CH2CH2CH=CH2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| RFA-10M | Ph | –CH2CH2CH2CH3 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| RFA-10m | Ph | –CH2CH2CH2CH3 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| RFA-11M | Ph | H | ≤0.063 | ≤0.063 | ≤0.063 |

| RFA-11m | Ph | H | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| RFA-12M | 4-MeOPh | H | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.125 |

| RFA-12m | 4-MeOPh | H | ≤0.063 | ≤0.063 | ≤0.063 |

| RFA-13M | 4-FPh | H | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 |

| RFA-13m | 4-FPh | H | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| RFA-14M | 2-IPh | H | 16 | 16 | 32 |

| Rifabutin | - | - | ≤0.063 | ≤0.063 | ≤0.063 |

| Vancomycin | - | - | 2 | >64 | >64 |

Results

Antibacterial activity of rifastures (RFA) 1–14 was assessed by the broth microdilution assay in 96-well plate format (Table 1) [18]. Among the six species of bacteria represented by the ESKAPE panel, the rifastures were selective growth inhibitors of Gram-positive Enterococcus faecium and Staphylococcus aureus. The four other Gram-negative members, namely Klebsiella pneumoniae (ATCC 700603), Acinetobacter baumannii (ABS075-UW), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 15442), and Enterobacter cloacae (ATCC 13047), were not susceptible at 64 μg ml−1. This indicates a spectrum specificity for the rifastures, beyond that of M. tuberculosis, and now includes both vancomycin-resistant forms of E. faecium and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). Thirteen of the rifastures displayed MICs ≤ 1 μg ml−1 against the MRSA COL strain, ten maintained this activity against the vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA HIP14300) and eight were equally potent against vancomycin-resistant enterococcus (VRE HF50104); however, none of the rifastures in this study were found to inhibit the growth of rifampin-resistant S. aureus strain Mu50 at 64 μg ml−1.

In the preliminary analysis, RFA-1, −11, and 12 showed comparable bioactivity to rifabutin. The breadth of the structures having such potencies, reflects a structure–activity relationship that allows for considerable tolerance in the 2,6-diaryl substitution of the spiroketal ring, as well as the configuration of the stereocenters on the ring. Anti-MRSA and anti-VRE was the greatest among the N-allyl analogs (i.e., RFA-1 to RFA-8) when unsubstituted phenyl (Ar) groups were bound. Moreover, substituted phenyl groups with smaller ring moieties (i.e., MeO, F) attached were greater in activity compared to those with larger attached (i.e., Br, I), which was particularly distinguishable by the VRE data.

Select RFAs were additionally assessed for their ability to decelerate S. aureus COL growth (Fig. 3a). From a 105 cfu ml−1 starter culture, RFA-1M (MIC 0.125 μg ml−1) and rifabutin (MIC ≤ 0.063 μg ml−1) exhibited comparable inhibitory effects to suppress MRSA growth over a 24 h period. By comparison, RFA-3m (MIC 4 μg ml−1) and RFA-11M (MIC ≤ 0.063 μg ml−1) showed differing abilities to slow the rate of growth, which their MICs reflected.

Fig. 3.

Inhibitory effects of rifastures (RFA) and rifamycin standards on S. aureus growth. a Comparison of growth inhibition by optical density measurements (600 nm). Samples were tested in duplicate at 1 × MIC against S. aureus COL. b Comparison of minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) where MBC50 and MBC90 represents reduction in cfu/ml by 50% and 90%, respectively. Samples were tested in triplicate at 0.25 to 4 × MIC against S. aureus CBD-635. Percent recovery was calculated based on cfu ml−1 in comparison to DMSO control. MBC50 and MBC90 values were calculated using linear regression of the percent recovery compared to no-treatment controls. c Comparison of minimum biofilm eradication concentrations (MBECs) where MBEC50 and MBEC90 corresponds to reduction in the viability of cells within the biofilm by 50% and 90%, respectively. Samples were tested in triplicate at 0.25 to 4 × MIC against S. aureus CBD-635. Percent recovery was calculated based on cfu ml−1 in comparison to DMSO control

The bactericidal and antibiofilm activities of RFA-1M were further determined in S. aureus CBD-635 [19, 20]. Figure 3b shows that RFA-1M exhibits comparable bactericidal activity at 1 × MIC to rifabutin and rifampin. Comparison of minimum biofilm eradication concentrations also revealed that RFA-1M may be a greater effector of S. aureus biofilm dispersion than rifabutin and rifampin (Fig. 3c). To this end, the ability of an antibiotic to penetrate biofilms and act on the subsurface bacteria is partly influenced by its physiochemical properties. Studies have shown that nonpolar antibiotics (e.g., rifampin, ciprofloxacin) are more effective than polar antibiotics (e.g., aminoglycosides) at penetrating bacterial biofilm matrices [21]. The increased lipophilicity of analog RFA-1M (clogP 5.44) compared to rifabutin (clogP 3.74) and rifampin (clogP 2.75) [22] could account for the enhanced antibiofilm activity against S. aureus.

In a final study, the cytotoxicity of RFA-1M was compared to rifabutin in human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells. The cell survival data revealed that analog RFA-1M was significantly less toxic at concentrations 50 and 100 μg ml−1 (Fig. 4). These results combined with the expanded antibacterial testing are very encouraging to warrant further development of aryl-substituted spiropiperidyl rifastures.

Fig. 4.

Cytotoxicity of compounds against HEK293. Cells were seeded and allowed to grow for 24 h prior to incubation with compounds for 48 h. Results were calculated based on DMSO controls. Error bars represent ± SEM of three replicates

The rifamycins are a valuable antibiotic class for the treatment of invasive infections due to their bactericidal potency, narrow activity spectrum, and ability to penetrate tissues and bacterial biofilms. Despite these advantages, most rifamycins can only be administered with other antibiotics due to rapid resistance development when used alone [23]. The major exception is oral rifaximin (Xifaxan®) for traveler’s diarrhea, which due to its low absorption, achieves supratherapeutic levels in the small intestines to eradicate the infection [24]. Another clinical attribute of rifamycins is their inducing effect on cytochrome enzymes that can decrease the blood levels of other medications taken by the patient (e.g., warfarin) [25]. Research on semi-synthetic rifastures could therefore lead to the discovery of new rifamycin antibiotics with better PK/PD parameters. Accordingly, investigations on their CYP3A-inducing properties, propensity for resistant development in MRSA, and oral bioavailability in mice will be the focus of future studies.

Acknowledgements

Financial support by Asturpharma S.A. and the projects PC-CIS01-22 (FICYT) and PR-01-GE-9 (Grupo de Excelencia FICYT) from the Consejería de Educación y Cultura del Principado de Asturias, and by Banco de Santander-Universidad de Oviedo (CEI “Ad Futurum” 10.01.633B.481.60) is gratefully acknowledged. This work was also supported in part by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health under award numbers AI151970 (T.E.L) and AI124458 (L.N.S.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Sensi P, Margalith P, Timbal M. Rifomycin, a new antibiotic; preliminary report. Farmaco Ed Sci. 1959;14:146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riva S, Silvestri LG. Rifamycins: a general view. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1972;26:199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lounis N, Rosceigno G. In vitro and in vivo activities of new rifamycin derivatives against mycobacterial infections. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:3229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Floss HG, Yu TW. Rifamycin-mode of action, resistance, and biosynthesis. Chem Rev. 2005;105:621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prelog V, Oppolzer W. Ansamycins, a novel class of microbial metabolites. Helv Chim Acta. 1973;56:2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallo GG, Martinelli E, Pagani V, Sensi P. The conformation of rifamycin S in solution by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Tetrahedron. 1974;30:3093. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maggi N, Pasqualucci CR, Ballota R, Sensi P. Rifampicin: a new orally active rifamycin. Chemotherapy. 1966;11:285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallo GG, Radaelli P. Rifampin. In: Florey EK, editor. Analytical profiles of drug substances. New York: Academia Press; 1976.p. 467–513 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wehrli W, Knusel F, Schmid K, Staehelin M. Interaction of rifamycin with bacterial RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1968;61:667–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wehrli W, Staehelin M. The rifamycins—relation of chemical structure and action on RNA polymerase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1969;182:24–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sensi P Recent progress in the chemistry and biochemistry of rifamycins. Pure Appl Chem. 1975;41:15. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sensi P, Maggi N, Füresz S, Maffii G. Chemical modifications and biological properties of rifamycins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1966;6:699–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lancini G, Zanichelli W. Structure-activity relationships in rifamycins. In: Perlmann D, editor. Structure–activity relationship among the semisynthetic antibiotics. New York: Academic Press; 1977. p. 531–600. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barluenga JM, Aznar Gomez F, Cabal Naves M-P, Garcia Delgado A-B, Valdes Gomez C. Preparation of spiropiperidyl rifamycin derivatives for therapeutic use in the treatment of mycobacterial infections. Spanish patent ES 2 246 155 A1, 2005; International patent PCT WO 2006/027397 A1; European patent: EP 1 783 129 A1; US patent: US 2007/0225266 A1. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barluenga J, Aznar F, García AB, Cabal M-P, Palacios JJ, Menéndez MA. New rifabutin analogs: synthesis and biological activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:5717–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubio E, Merino I, García A-B, Cabal M-P, Ribas C, Bayod-Jasanada M. NMR spectroscopic analysis of new spiro-piperidylrifamycins. Magn Reson Chem. 2005;43:269–82. Erratum: Magn Reson Chem. 2006;44:654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.García A-B, Palacios JJ, Ruíz M-J, Barluenga J, Aznar F, Cabal M-P, García JM, Díaz N. Strong in vitro activities of two new rifabutin analogs against multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:5363–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.M07-A10. Methods for dilution antimicrobial tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard. 10th ed. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleeman R, Van Horn KS, Barber MM, Burda WN, Flanigan DL, Manetsch R, Shaw LN. Characterizing the antimicrobial activity of N2,N4-disubstituted quinazoline-2,4-diamines toward multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61:e00059–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carroll RK, Burda WN, Roberts JC, Peak KK, Cannons AC, Shaw LN. Draft genome sequence of strain CBD-635, a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA100 isolate. Genome Announc. 2013;1:e00491–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lebeaux D, Ghigo J-M, Beloin C. Biofilm-related infections: bridging the gap between clinical management and fundamental aspects of recalcitrance toward antibiotics. Microbiol Mol Bio Rev. 2014;78:510–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothstein DM. Rifamycins, alone and in combination. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6:a027011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Darkoh C, Lichtenberger LM, Ajami N, Dial EJ, Jiang Z-D, DuPont HL. Bile acids improve the antimicrobial effect of rifaximin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3618–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burman WJ, Gallicano K, Peloquin C. Comparative pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the rifamycin antibacterials. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2001;40:327–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]