Abstract

Childhood diagnoses of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have increased dramatically in the U.S. in recent decades. Prior research has alluded to the possibility that high levels of parental intervention in school are associated with increased diagnoses of ADHD, but this relationship remains understudied. This study investigates: 1) whether the children of intervening parents are more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD, and; 2) whether parental intervention moderates the extent to which children’s pre-diagnosis behavioral problems and exposure to strict educational accountability policies predict ADHD diagnosis. Analyses of longitudinal, population-level data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten Cohort of 1998–99 (n=9,820) reveal that a standard deviation increase above the mean on parental intervention in school is associated with a 20% increase in the odds of ADHD diagnosis among elementary school children. This relationship is robust to differences in children’s pre-diagnosis behavioral problems, academic achievement, parental knowledge of/exposure to ADHD, and school selection, and can arise because parents who intervene in school on average exhibit heightened sensitivity to behavioral problems and academic pressure from accountability-based educational policies. In light of prior work establishing both social class and racial/ethnic differences in parental intervention in school, this positive relationship between parental intervention in school and children’s diagnoses of ADHD may carry important implications for the production of inequality in children’s mental health and educational opportunities.

Keywords: ADHD, Mental Health, Disability, Education, Families, Children

1. Introduction

With the rise of neoliberalism and accountability standards in education, including the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, schools have become increasingly academically focused at younger ages (Brosco and Bona 2016; Koretz 2008; Russell 2011). As a result, teachers and parents face increasing pressure to explain children’s under-achievement (Figlio and Loeb 2011; Harry and Klingner 2007) and student differences are increasingly recognized with disability labels, including through diagnoses of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Cormier 2012; Sax and Kautz 2003). ADHD is today’s most common childhood behavioral disorder in the United States. As of 2016, 6.4 million (11%) American children ages 4–17 had been diagnosed based on parental report (Xu et al. 2018). Rates of childhood ADHD diagnosis have doubled over the last 25 years, from roughly 5% in 1991 to 11% in 2016 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013; Xu et al. 2018).

One reason for the rise in diagnoses may be that ADHD medications are proven to improve attention and concentration (Smith and Farah 2011; Swanson, Baler and Volkow 2010)—behaviors linked to children’s school success (Duncan et al. 2007; Hinshaw and Scheffler 2014). For roughly two-thirds of diagnosed children, diagnosis is accompanied by stimulant medications like Ritalin and Adderall (Danielson et al. 2018). Diagnoses can also help facilitate children’s access to educational accommodations like extra testing time through a 504 Plan or an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) (Gius 2007).

Prior research has alluded to a possible relationship between parents’ intervention in school and their children’s ADHD diagnoses (Blum 2015; King, Jennings and Fletcher 2014; Ong-Dean 2009), but this relationship has not been tested using population-level data. “Parental intervention in school” refers to the routine ways in which parents participate in their children’s schooling—even when their children are not having problems at school—such as by attending parent-teacher conferences and school fundraisers. Prior work shows that intervening parents are often aware of the importance of children’s attention and concentration skills for school success—and able to help their children develop these skills (Calarco 2018; Lareau 2011). Intervention in school can further help parents understand their children’s standing relative to the school’s academic and behavioral expectations and help ensure that their children receive services, supports, and opportunities to maximize their educational success (Calarco 2018).

When it comes to ADHD diagnoses, intervening parents may thus be more sensitive to their children’s levels of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity and more likely to internalize school-based academic pressure, such as that from educational policies that incentivize raising student test scores (King, Jennings and Fletcher 2014). For example, when school funding is tied to school academic performance, schools are more likely to emphasize children’s development of behaviors like attention that support high achievement (Koretz 2008; Mittleman and Jennings 2018). Intervening parents may respond to this pressure by being more likely than non-intervening parents to internalize and act on the school’s academic emphasis by having their child evaluated and potentially diagnosed with ADHD (King, Jennings and Fletcher 2014).

This study uses population-level data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten Cohort of 1998–99 (ECLS-K) to examine: 1) whether the children of intervening parents are more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD, and; 2) whether parental intervention moderates the extent to which children’s pre-diagnosis behavioral problems and exposure to strict educational accountability policies predict ADHD diagnosis. Crucially, analyses control for differences in children’s prior academic achievement, behavioral problems, family social class, and schools—factors known to shape both parental intervention and disability diagnoses (Shifrer 2018; Shifrer and Fish 2020). Understanding these relationships carries important implications for the production of inequality in children’s mental health and educational opportunities, a point on which I expand in the Discussion.

1.1. Parents’ intervention in school and children’s subsequent diagnoses of ADHD

To what extent is parents’ intervention in school positively associated with children’s later diagnoses of ADHD? Parents’ intervention in school might be positively associated with children’s later diagnoses of ADHD because intervention helps parents to develop the knowledge and skills necessary to detect developmentally abnormal child behaviors, navigate education and disability policies, and understand the implementation of these policies in their children’s schools.

Today, parents are expected to be “actively involved in their children’s education—attending parent-teacher conferences, helping their child with homework, and monitoring their children’s academic progress and social development” in order to identify and address any problems that might arise (Ong-Dean 2009: 1). Drawing on in-depth interviews with a diverse group of 48 mothers trying to understand whether their child had an “invisible disability” like ADHD, one study found that it was partly through navigating their children’s schools that the mothers learned that disabilities like ADHD could be “both real…and cultural inventions specific to our time and place” (Blum 2015: 7). Subtle differences in children’s behaviors became consequential through “the medicalization of ‘precarious normality’ within a larger social landscape fueled by parents’ anxieties…about an uncertain world where perhaps only the most vigorous-brained will succeed” (Blum 2015: 7). Thus, it was largely through routine school intervention that preceded their children’s diagnoses that the mothers came to understand how the school understood the boundaries of so-called “invisible disabilities” like ADHD. Thus: Parental intervention in school will be positively associated with children’s diagnoses of ADHD, net of differences in children’s pre-diagnosis ADHD-related behaviors, prior academic achievement, and other child, family, school, and state characteristics (hypothesis 1).

1.2. Moderating effects of parental intervention on the relationship between pre-diagnosis behavioral severity and ADHD diagnosis

When it comes to ADHD diagnosis, are parents with high levels of intervention in school more sensitive to increases in children’s pre-diagnosis inattention and/or hyperactivity/impulsivity than parents with low levels of intervention in school? Prior research suggests that the greater behavioral sensitivity of intervening parents may partly arise from increased contact with teachers and school staff (Horvat, Weininger and Lareau 2003). Increased contact can help parents learn about and understand teachers’ assessments of their child and thus recognize when their child’s inattention and hyperactivity problems are impeding academic performance (Blum 2015).

Given the lack of a biological marker for ADHD, teachers’ assessments of student behavior are a main criterion considered by medical professionals during evaluation. A child must exhibit “functional impairment in at least two settings,” usually home and school (American Psychiatric Association Task Force 1994). By increasing parents’ contact with teachers and school staff, parental intervention in school may also facilitate parents’ attentiveness to teacher perceptions of their child’s inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity, and thus the parent’s awareness of whether their child is likely to meet diagnostic criteria. Through this channel, parental intervention in school can also enhance parents’ ability to make the strongest—and most seemingly objective, scientific, and legally justifiable—claims that their children require particular diagnoses to meet their educational needs (Blanchett 2010; Sleeter 2010). By this logic:

Parental intervention in school will moderate the relationship between children’s pre-diagnosis inattention and/or hyperactivity/impulsivity behaviors and diagnosis; these pre-diagnosis behaviors will be more strongly and positively associated with ADHD diagnosis among the children of parents with higher as opposed to lower levels of intervention in school (hypothesis 2).

1.3. Moderating effects of parental intervention on the relationship between accountability-based academic pressure and ADHD diagnosis

When it comes to ADHD diagnosis, are parents with high levels of intervention in school also more sensitive to academic pressure, such as that from educational accountability policies, than parents with low levels of intervention in school? In the 1990s, the U.S. educational system entered an era of “consequential school accountability” in which roughly two-thirds of states began evaluating primary school performance based on student scores on state-sponsored standardized tests (Figlio and Loeb 2011). Schools with average scores below set proficiency thresholds risked losing government funding and facing other negative sanctions (Figlio and Loeb 2011).

Existing studies already have established that these educational accountability policies, with their focus on raising student test scores, are associated with children’s greater diagnoses of ADHD and subsequent use of stimulant medications (Bokhari and Schneider 2011; King, Jennings and Fletcher 2014; Schneider and Eisenberg 2006). One reason for this relationship is that ADHD medications have been shown to help improve diagnosed children’s behaviors, and by extension, their test performance (Swanson, Baler and Volkow 2010) and that of classmates (Aizer 2008). Diagnoses also open the possibility of extra school funding to support diagnosed students’ specialized accommodations (Morrill 2018).

By increasing pressure on teachers and parents to explain students’ underachievement, accountability-based education policies may be associated with an increase in ADHD diagnoses particularly among children with intervening parents. Intervening parents may be more likely to be directly exposed to diagnosis pressure from teachers through their heightened involvement at school and more likely to have internalized the school’s pressure to raise student achievement. As a result, intervening parents may be more likely to have their child evaluated for ADHD by a medical professional. For example, Sax and Kautz (2003) found that over half of diagnoses were first suggested by a teacher or school staff. Cormier (2012) further revealed that many parents report having had repeated conversations with teachers and school personnel encouraging them to have their child evaluated and treated for ADHD. Conditional on diagnosis, school personnel have been shown to also pressure parents to adhere to medication regimens (Arcia et al. 2004).

However, the conditions under which these policies are positively associated with diagnoses and medication treatment remain unclear. All schools are mandated to administer state standardized exams in the third through eighth grades regardless of their schools’ prior achievement. Therefore, although the threat of negative sanctions is greatest for low-performing schools (Figlio and Loeb 2011), educational accountability policies create a broader culture in which all schools become more focused on children’s early development of academic skills (King, Jennings, and Fletcher 2014). Intervening parents may be more likely to internalize this school culture and thus more likely than non-intervening parents to have their children evaluated, diagnosed, and treated for ADHD. Thus:

Parental intervention in school will moderate the relationship between children’s exposure to strict accountability policies and diagnosis; exposure to strict accountability policies will be more strongly positively associated with ADHD diagnosis among the children of parents with higher as opposed to lower levels of intervention in school (hypothesis 3).

2. Data and methods

2.1. Data

While prior research has alluded to the possibility of a relationship between parental intervention in school and their children’s diagnoses with ADHD, existing suggestive evidence has come largely from small-scale studies, raising questions about the generalizability of findings to the population level. The present study tests this relationship using population-level and also examines whether parental intervention moderates the extent to which children’s pre-diagnosis inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity and/or exposure to academic pressure from accountability policies predict future diagnoses of ADHD. Data come from the restricted-use Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten Cohort of 1998–99 (ECLS-K), a school-based probability sample initially including 21,410 kindergartners in 1998–99 from 1,280 public (72%) and private (28%) schools. Between 1 and 24 students are sampled per school. To remain in this study’s longitudinal sample, children must have been present in all five rounds of data collection between the fall of kindergarten and the spring of 5th grade (not counting the wave of data collection from fall of 1st grade that included only a 30% subsample). Only a 50% subsample of those in the fall kindergarten baseline sample who transferred schools prior to a given follow-up was eligible for inclusion, reducing the longitudinal sample to 18,080 in 1st grade, 16,670 in 3rd grade, and 12,030 in 5th grade. Sample sizes are rounded to the nearest ten per the restricted-use data agreement.

Of the 12,030 kindergartners eligible for sampling in the 5th grade wave, 90% are present in that wave, resulting in a 5th grade sample of 10,860. This 90% retention rate is on par with the highest among longitudinal studies of children, families, and schools (Tourangeau et al. 2009). Nonetheless, the 10% sample attrition is consequential. Combined with shifts in the composition of the U.S. population since 1998–99, the 5th grade sample is not nationally representative of all U.S. 5th graders in 2003–04: these children are more likely to be white, have mothers with slightly higher educational levels, and have slightly lower inattentive behavior scores at baseline. However, the 5th grade sample is not significantly different from the baseline sample in their kindergarten achievement scores or hyperactive/impulsive behaviors scores.

Of the 10,860 children in the 5th grade sample, 9.6% (N=1,050) lack information on the outcome variable (ADHD diagnosis) or kindergarten school identification number (used to adjust for within-school clustering), reducing the working sample to 9,820 children.

2.2. Treatment of missing data

Of the working analytic sample of 9,820 children, 11.5% (N=1,130) lack complete information on predictor variables. Item-missingness on the predictors is more common among boys, African-Americans, and children with mothers with less than a college degree. Multiple imputation of twenty datasets is used to address item-missingness on predictor variables. ADHD diagnosis is included in the imputation equation but children originally missing on this outcome are excluded from all analyses through listwise deletion, per Von Hippel (2007).

2.3. Measures

Dependent variable.

ADHD diagnosis between 1st and 5th grade1 was identified when the parent answered “yes” to all three of the following questions in a given wave: (a) “Has the child been evaluated by a professional in response to a problem in paying attention, learning, behaving, or in activity level?” (b) “Has the child received a diagnosis by this professional?” and; (c) “Was the diagnosis for ADHD, ADD, or hyperactivity?” Following Morgan et al. (2013) and Tourangeau et al. (2009), coding children as undiagnosed if their parents answered ‘no’ to any of these questions limits the extent of misreporting. Misreporting might otherwise occur, for example, if parents were told their child “has ADHD” without the child having received a formal evaluation and diagnosis from a medical professional. That diagnosis occurred during the 1st-5th grade diagnostic observation period was confirmed using parent report of “year of first [ADD/ADHD] diagnosis.” To ensure that the predictors/controls measured in kindergarten precede diagnosis, analyses excluded the 10.5% of (N=70) diagnosed children who were diagnosed before/during kindergarten; however, substantive findings did not change with their inclusion. Supplemental analyses were additionally replicated using ‘ADHD diagnosis accompanied by medication receipt’ to capture the 52% of diagnosed children who received medication treatment following diagnosis and results did not differ significantly from those in the main text.

Parental intervention in school in kindergarten is a summed and standardized index of six dichotomous indicators capturing whether an adult in the household had attended in the past year the school’s: open house or back-to-school night, PTA/PTO meeting, regularly scheduled parent-teacher conference, fieldtrip/classroom event, committee meeting or fund-raiser.

Child pre-diagnosis ADHD-related behavioral problems scores from first grade/wave before diagnosis include both teacher and parent ratings from the inattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity, and oppositional defiant subscales of the psychometrically validated Social Rating Scale (see Tourangeau et al. 2009 for complete details). Subscales average across their respective items, ranging from 0 = “rarely” to 3 = “always,” and are sample mean-centered. Importantly, results from sensitivity analyses using children’s complete externalizing behaviors and approaches to learning scales (rather than ADHD-specific behaviors) were virtually identical (see Online Appendix Tables A.1–A.2).

School accountability in kindergarten is a binary indicator that follows the Dee and Jacob (2011) classification for whether or not the child’s state of residence in kindergarten was one of the thirty listed in the Online Appendix that had consequential accountability standards in place during the 1998 to 2003 period.2

Key control variables.

Family social class background in kindergarten is a composite, standardized scale consisting of mother/female guardian’s and father/male guardian’s educational attainment, household income, and parental occupational prestige (see chapter 7, pages 8–11 of Tourangeau et al. 2009). Following precedent (Owens 2020), I then construct three social class indicators: the bottom quartile constitutes lower-class, the middle two quartiles middle-class and the top quartile upper-class.

Child racial/ethnic background is based on parental report, with multiracial children coded with their non-White group membership: Black, Hispanic, Asian/Other, or White (the reference).

Child standardized reading and math achievement scores in kindergarten are based on psychometrically validated, untimed tests each containing 50–70 items and emphasizing grade-appropriate reading skills/comprehension or conceptual number sense, properties, and operations skills (Tourangeau et al. 2009).

Other parenting measures, including:

Parental investment in child extracurricular activities and structured leisure, a summed index of ten dichotomous indicators for whether the child has ever, outside school hours, participated in: dance lessons, organized athletic activities, clubs or recreational programs, music lessons, art classes or lessons, organized performing arts programs, and visited the library, museum, zoo, and a live show or concert. Parent educational expectations, from a variable asking the primary caregiver “how far do you expect the child will go in school.” I construct a binary variable capturing whether the parent expects the child to obtain a graduate degree, coding “master’s degree” and “PhD, MD, or other higher graduate degree” as 1 and all other responses as 0. Parental cognitive stimulation, a summed index of 11 items of the average number of days per week that the primary caregiver(s) engages in the following activities with the child: reading books, telling stories, singing to/with, housework, chores, games, time in nature, building blocks/toys, sports, pictures/artwork, and helping child read. Number of books at home, a count of the number of books at home from 0–200. Each measure is sample mean-centered.

Other child, family, classroom, and state controls in kindergarten.

These measures, listed in Table 1, adjust for potential confounding and test key alternative explanations (see the Online Appendix for further discussion).

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations or Proportions for Variables Used in the Analyses (N=9,750)

| Mean or Prop. | SD | Min. | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variable | ||||

| ADHD Diagnosis Kindergarten (K)-5th Grades | 0.07 | 0 | 1 | |

| Parenting in Kindergarten | ||||

| Parental Intervention in School (std.) | 0.00 | 1.00 | −3 | 3 |

| Child Extra-Curricular Activities and Structured Leisure Time (std.) | 0.00 | 1.00 | −1 | 4 |

| Parent Expects Child to Obtain a Graduate Degree | 0.29 | 0 | 1 | |

| Cognitive Stimulation at Home (std.) | 0.00 | 1.00 | −3 | 3 |

| Number of Books at Home (std.) | 0.00 | 1.00 | −1 | 2 |

| Child Pre-Diagnosis ADHD-Related Behavioral Problems in First Grade/Wave Prior to Diagnosis | ||||

| Inattentive Behaviors Score (Teacher) | 0.00 | 0.88 | −1 | 2 |

| Hyperactivity Behaviors Score (Teacher) | 0.00 | 0.69 | −1 | 2 |

| Oppositional Defiance Disorder or Conduct Disorder Behaviors Score (Teacher) | 0.00 | 0.70 | −1 | 2 |

| Internalizing Problems Score (Teacher) | 0.00 | 0.62 | −1 | 2 |

| Inattentive Behaviors Score (Parent) | 0.00 | 0.73 | −1 | 2 |

| Hyperactivity Behaviors Score (Parent) | 0.00 | 0.69 | −1 | 2 |

| Oppositional Defiance Disorder or Conduct Disorder Behaviors Score (Parent) | 0.00 | 0.53 | −1 | 2 |

| Child Pre-Diagnosis Achievement Scores in Kindergarten | ||||

| Reading Achievement Score (std.) | 0.00 | 1.00 | −3 | 4 |

| Math Achievement Score (std.) | 0.00 | 1.00 | −3 | 4 |

| Classroom and Early Care Context in Kindergarten | ||||

| Average Behavior of Students in Kindergarten Class (Teacher) | 2.48 | 0.79 | 0 | 4 |

| Child Age (Months) at Kindergarten Entry | 65.58 | 4.35 | 37 | 83 |

| Child has been in Non-Family Care (e.g., Daycare or Pre-K) | 0.50 | 0 | 1 | |

| Number of Other Children in Household | 1.55 | 1.14 | 0 | 11 |

| Family Social Class | ||||

| Upper-Class Family | 0.25 | 0 | 1 | |

| Middle-Class Family | 0.50 | 0 | 1 | |

| Lower-Class Family | 0.25 | 0 | 1 | |

| Family Structure in Kindergarten | ||||

| Two Biological Parents in Household | 0.74 | 0 | 1 | |

| Single Mother | 0.17 | 0 | 1 | |

| Stepfather or Mother’s Cohabiting Partner | 0.05 | 0 | 1 | |

| Single Father | 0.02 | 0 | 1 | |

| Adopted Parents | 0.03 | 0 | 1 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 0.60 | 0 | 1 | |

| Black | 0.11 | 0 | 1 | |

| Hispanic | 0.18 | 0 | 1 | |

| Other Race/Ethnicity | 0.12 | 0 | 1 | |

| Other Demographic Characteristics | ||||

| Male | 0.51 | 0 | 1 | |

| Child Born Weighing Less than 5.5 lbs. (Low Birthweight) | 0.08 | 0 | 1 | |

| Child Not Covered by Insurance | 0.17 | 0 | 1 | |

| Current Age of Primary Caregiver (Usually Biological or Social Mother) | 33.93 | 6.42 | 18 | 83 |

| Mother Has Clinically Depressive Symptoms (CES-Depression Score >9) | 0.17 | 0 | 1 | |

| State Characteristics in Kindergarten | ||||

| Child Lives in Strict Consequential Accountability State | 0.71 | 0 | 1 | |

| Proportion of State Population Receiving Private Health Insurance Coverage in | ||||

| 1998 (Census Data) | 0.68 | 0.08 | 0 | 1 |

| Proportion of State Population Receiving Public Health Insurance Coverage in | ||||

| 1998 (Census Data) | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0 | 1 |

| State Per Pupil Expenditure in 1998–99 (Common Core of Data) | 6525.72 | 1253.61 | 4210 | 10145 |

| Average Student-Teacher Ratio in the State in 1998–99 (Common Core of Data) | 17.76 | 2.95 | 13 | 24 |

| Region | ||||

| Lives in Midwest | 0.27 | 0 | 1 | |

| Lives in Northeast | 0.18 | 0 | 1 | |

| Lives in West | 0.22 | 0 | 1 | |

| Lives in South | 0.31 | 0 | 1 | |

Source: Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten Cohort of 1998–99.

2.4. Models

Given that levels of parental intervention are not randomly-assigned to families, analyses must address the possibility that the focal relationship of interest between parental intervention and subsequent ADHD diagnoses could be driven by differences in factors such as children’s pre-existing academic difficulties, which can differentially motivate parents’ intervention in school (Shifrer 2018). To address this possibility, analyses control for a robust set of child, family, classroom, and state characteristics detailed in Table 1. These controls allow me to compare the diagnostic outcomes of children who had comparable baseline academic achievement, pre-diagnosis ADHD-related behavioral problems, and other characteristics, but whose parents differed in levels of parental intervention in school in kindergarten.

Another key challenge to estimating the relationship between parental intervention in school and children’s diagnoses of ADHD is that differences in parental intervention may not only reflect parenting differences across families, but also differences in schools’ abilities to encourage parents to pursue diagnosis. Thus, the relationship between parental intervention and ADHD diagnoses may be confounded by underlying differences in the schools attended by intervening and non-intervening parents. To address this possibility, I use school fixed effect models to test whether the relationship between exposure to parent intervention and ADHD diagnoses persists even among children attending the exact same schools. To address possible non-random selection into school moves based on parental intervention and family social class, I additionally restrict certain models to include only children not changing elementary schools.

The first analyses use logit regressions to examine whether parental intervention in school in kindergarten is linked to later ADHD diagnosis (hypothesis 1), per Equation 1:

| (1) |

In all equations, x′is is a matrix of control variables described above and detailed in Table 1 and γs is a vector of school fixed effects. Subsequent models include school fixed effects to address the issue of non-random school assignment and then also restrict the working sample to children not changing elementary schools. (Exploratory analyses also examined the relationship between the other kindergarten parenting measures displayed in Table 1 and childhood ADHD diagnosis and found parental intervention in school to be the only consistently significant predictor of the parenting measures examined.)

The second analyses use logit regressions with interactions between parental intervention in kindergarten and children’s pre-diagnosis inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity to examine whether each unit increase in these ADHD-related behavior problems is more strongly associated with ADHD diagnosis among parents with greater as opposed to lesser intervention in school (hypothesis 2), per Equation 2 (without and then with school fixed effects):

| (2) |

The third analyses estimate interactions between school-based accountability pressure and parental intervention in school using a three-level mixed effects logit regression to examine whether greater parental intervention amplifies the relationship between accountability pressure and ADHD diagnosis (hypothesis 3). The three-level mixed effects logit regressions include random intercepts (constants only) at the school and state levels to adjust for non-independent errors among children (level 1) nested within schools (level 2) and states (level 3), per Equation 3:

| (3) |

The fixed component of the model includes: acctk, the state level indicator for whether the child lives in an accountability state, involvijk, the child level measures for parental intervention, and x′is, the control variables described above and detailed in Table 1. The random error has three components: u0j and u1k, the vector of random intercepts for each school (level 2) and state (level 3), respectively, and εijk, the child (level 1) error. Finally, sensitivity analysis used ‘ADHD diagnosis between 3rd and 5th grades’ in Table 4 to capture diagnoses during the specific grades when accountability testing occurs; results were substantively similar (and not statistically significantly different) from those in the main text.

Table 4.

Hypothesis 3: Relationships between Accountability Pressure, Parental Intervention in School, and Elementary School Diagnoses of ADHD1 (Displaying Odds Ratios from Three Level Mixed Effects Logit Regression)

| (1) |

|

|---|---|

| Child Lives in a State with Consequential Accountability in Kindergarten |

1.51** (0.21) |

| Parental Intervention in School in Kindergarten (std.) |

0.99 (0.09) |

| Parental Intervention in School in Kindergarten (std.) * Accountability |

1.31* (0.14) |

| Child Reading Achievement Score in Kindergarten (std.) | 1.06 (0.08) |

| Child Math Achievement Score in Kindergarten (std.) | 0.71*** (0.06) |

| Child Inattentive Behaviors Score in First Grade/Wave Prior to Diagnosis (Teacher) | 1.97*** (0.14) |

| Child Hyperactivity Behaviors Score in First Grade/Wave Prior to Diagnosis (Teacher) | 1.38*** (0.10) |

| Child Oppositional Defiant or Conduct Disorder Behaviors Score in First Grade/Wave Prior to Diagnosis (Teacher) | 1.18+ (0.11) |

| Child Internalizing Problems Score in First Grade/Wave Prior to Diagnosis (Teacher) | 0.98 (0.07) |

| Child Inattentive Behaviors Score in First Grade/Wave Prior to Diagnosis (Parent) | 1.77*** (0.13) |

| Child Hyperactivity Behaviors Score in First Grade/Wave Prior to Diagnosis (Parent) | 1.99*** (0.14) |

| Child Oppositional Defiant or Conduct Disorder Behaviors Score in First Grade/Wave Prior to Diagnosis (Parent) | 1.35*** (0.12) |

| Middle-Class Family | 1.30* (0.17) |

| Upper-Class Family | 1.40* (0.24) |

| Black | 0.29*** (0.05) |

| Hispanic | 0.34*** (0.06) |

| Other Race/Ethnicity | 0.44*** (0.08) |

| Random-Effects Parameters | |

| Level 3, state: σ2(constantstate) | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Level 2, school: σ2(constantschool) | 0.18 (0.10) |

| N | 9520 |

Displaying odds ratios for the fixed component of the model and variance estimates for constants in the random-effects for school (level 2) and state (level 3); standard errors in parentheses.

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001.

Model controls for child pre-diagnosis ADHD-related behavioral problems, pre-diagnosis math and reading scores, the other parenting measures, family and demographic characteristics, classroom and early care context, and state and region characteristics (see Table 1).

Results remain comparable when diagnosis is restricted to 3rd-5th grades, when accountability testing occurs.

Source: Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten Cohort of 1998–99.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

Table 1 reports means and standard deviations (or proportions) for the variables used in the analyses. In this sample, 6.8% of children are diagnosed with ADHD between 1st and 5th grade. This rate is consistent with the age-adjusted rate at the national level, where 6.8% of U.S. children ages 5–11 had been diagnosed with ADHD in 2002 (Dey, Schiller and Tai 2004). The overwhelming majority of diagnoses in my sample occurred between 3rd and 5th grade—the grades with accountability testing. Roughly half of diagnosed children received medication to help control behaviors following diagnosis and between one-quarter and one-third of diagnosed children received special education services.

At the start of elementary school, the average parent in the sample reports having attended roughly 3 of the 6 school events (e.g., an open house or back-to-school night or a PTA or PTO meeting) used to capture parental intervention in school, which equates to a mean score of 0 on the standardized parental intervention scale. 71% of children live in a state that had consequential educational accountability in place during the kindergarten to 5th grade period (1998–2003).

3.2. Parental intervention in school and childhood diagnoses of ADHD

To examine whether parental intervention in school is positively associated with childhood diagnoses of ADHD (hypothesis 1), Table 2 displays odds ratios from logit models that regress ADHD diagnosis on parental intervention, net of controls shown in Table 1. Model 1 establishes the baseline estimates when retaining the full sample of 9,750 children. It shows that children whose parents fall 1 SD above the mean on intervention in school on average experience a statistically significant 20% higher odds of elementary school ADHD diagnosis than those at the mean, net of pre-diagnosis ADHD-related behaviors, kindergarten test scores, and other controls (p<0.01).

Table 2.

Hypothesis 1 : Relationship between Parental Intervention in School and Elementary School Diagnoses of ADHD

|

Displaying Odds Ratios from Logit Regression |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Parental Intervention in School in Kindergarten (std.) | 1.20*** | 1 19** | 1.17* |

| (0.06) | (0.08) | (0.09) | |

| Child Reading Achievement Score in Kindergarten (std.) | 1.08 | 0.99 | 0.96 |

| (0.08) | (0.09) | (0.10) | |

| Child Math Achievement Score in Kindergarten (std.) | 0.73*** | 0.75** | 0.78* |

| (0.06) | (0.07) | (0.08) | |

| Child Inattentive Behaviors Score in First Grade/Wave Prior to Diagnosis (Teacher) | 1 90*** | 1 99*** | 2.03*** |

| (0.13) | (0.16) | (0.18) | |

| Child Hyperactivity Behaviors Score in First Grade/Wave Prior to Diagnosis (Teacher) | 1 41*** | 1 34*** | 1.31** |

| (0.10) | (0.12) | (0.13) | |

| Child Oppositional Defiant or Conduct Disorder Behaviors Score in First Grade/Wave Prior to Diagnosis (Teacher) | 1.17 | 1.29* | 1.38** |

| (0.11) | (0.14) | (0.17) | |

| Child Internalizing Problems Score in First Grade/Wave Prior to Diagnosis (Teacher) | 0.98 | 1.01 | 0.99 |

| (0.07) | (0.09) | (0.10) | |

| Child Inattentive Behaviors Score in First Grade/Wave Prior to Diagnosis (Parent) | 1.71*** | 1.68*** | 1.60*** |

| (0.12) | (0.13) | (0.14) | |

| Child Hyperactivity Behaviors Score in First Grade/Wave Prior to Diagnosis (Parent) | 1 90*** | 1 99*** | 2.03*** |

| (0.14) | (0.16) | (0.19) | |

| Child Oppositional Defiant or Conduct Disorder Behaviors Score in First Grade/Wave Prior to Diagnosis (Parent) Score in First Grade/Wave Prior to Diagnosis (Parent) | 1.35*** | 1.41*** | 1.28* |

| (0.12) | (0.14) | (0.15) | |

| Middle-Class Family | 1.31* | 1.27 | 1.31 |

| (0.16) | (0.19) | (0.23) | |

| Upper-Class Family | 1.40* | 0.93 | 0.96 |

| (0.23) | (0.19) | (0.22) | |

| Black | 0.28*** | 0.32*** | 0.37*** |

| (0.05) | (0.08) | (0.10) | |

| Hispanic | 0.34*** | 0.40*** | 0.49** |

| (0.06) | (0.09) | (0.12) | |

| Other Race/Ethnicity | 0.45*** | 0.58* | 0.64 |

| (0.08) | (0.14) | (0.17) | |

| School Fixed Effects | X | X | |

| Restricted Sample to Students not Changing Elementary | |||

| Schools | X | ||

| N | 9750 | 5250 | 4050 |

| Pseudo r-squared or r-squared | 0.26 | 0.36 | 0.37 |

Robust standard errors in parentheses (standard errors clustered by school in model 1, which excludes fixed effects).

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001.

All models control for child pre-diagnosis ADHD-related behavioral problems, pre-diagnosis math and reading scores, the other parenting measures, family social class and demographic characteristics, classroom and early care context, and state and region characteristics (see Table 1 for detailed list). Model 1 is the baseline logit model that includes all 9,750 children, model 2 adds school fixed effects and is thus restricted to the 5,250 children who attend a school where at least one sample child is diagnosed with ADHD, and model 3 is further restricted to those sample children with within-school variation in diagnosis who additionally do not change elementary schools.

Source: Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten Cohort of 1998–99.

The relationship between parental intervention and diagnosis may be confounded by previously unobserved differences in the schools attended by children from families with higher versus lower levels of parental intervention. To address this possibility, model 2 uses school fixed effects to examine this relationship among the subset of 5,250 children attending a school with at least one diagnosed sample child diagnosed with ADHD. Model 2 reveals that this relationship persists even among children attending the exact same schools: the odds of ADHD diagnosis are a statistically significant 19% greater for children whose parents fall 1 SD above the mean on school intervention relative to those at the mean, ceteris paribus (p<0.05).

Because parental intervention in school may be systematically related to school transfer (for example, if intervening parents are more likely to transfer their children after learning they may need a more specialized learning environment due to ADHD-related problems), model 3 of Table 2 includes only the 77% of the students in model 2 who did not change elementary schools. Results remain substantively unchanged.

3.3. Parental intervention in school as a moderator of the relationship between children’s pre-diagnosis ADHD-related behavioral problems and diagnosis

Increased parental attentiveness to early signs of behavioral difficulty offers one explanation for the greater diagnoses among children whose parents intervene at school (hypothesis 2). Strikingly, model 1 of Table 3 reveals that both teacher- and parent-rated pre-diagnosis inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity are statistically significant predictors of diagnosis, with a one unit increase above the mean associated with a 42% to 91% increase in the odds of ADHD diagnosis, depending on the rater and behavior. In addition to these significant main effects, results in model 1 are also consistent with hypothesis 2 when it comes to parental intervention as a moderator of the relationship between teacher-rated inattention problems and diagnosis: children whose parents fall 1 SD above the mean on school intervention on average experience 19% higher odds of diagnosis for a 1 point increase above the mean on teacher-rated inattention problems (1.02*1.17). This result persists even among children in the same schools (model 2). A directionally similar but non-significant pattern exists for the interaction between parental intervention and the other pre-diagnosis ADHD-related behavioral problems, consistent with prior work finding that teacher-rated inattention is more strongly related to later academic achievement than is hyperactivity (Duncan et al. 2007). To help address confounding from differences in parental knowledge of and exposure to ADHD—key alternate explanations—models control for family social class and region of the country, given dramatic differences in diagnostic prevalence rates along this latter dimension (Hinshaw and Scheffler 2014).

Table 3.

Hypothesis 2: Relationship between Children's Pre-Diagnosis ADHD-Related Behaviors, Parental Intervention in School, and Elementary School Diagnoses of ADHD (Displaying Odds Ratios from Logit Regressions)

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Child Pre-Diagnosis ADHD-Related Behaviors in First Grade/Wave Prior to Diagnosis | ||

| Inattentive Behaviors Score (Teacher) | 1.91*** | 2.01*** |

| (0.13) | (0.16) | |

| Hyperactivity Behaviors Score (Teacher) | 1 42*** | 1.36*** |

| (0.10) | (0.12) | |

| Inattentive Behaviors Score (Parent) | 1 71*** | 1.68*** |

| (0.12) | (0.13) | |

| Hyperactivity Behaviors Score (Parent) | 1 90*** | 1 98*** |

| (0.14) | (0.16) | |

| Parental Intervention in Kindergarten and Parenting*ADHD-Related Behavior Interactions | ||

| Parental Intervention in School (std.) | 1.02 | 1.03 |

| (0.07) | (0.08) | |

| Parental Intervention in School (std.) * Inattentive Behaviors Score (Teacher) | 1 17** | 1.17* |

| (0.07) | (0.08) | |

| Parental Intervention in School (std.) * Hyperactivity Behaviors Score (Teacher) | 1.05 | 1.05 |

| (0.06) | (0.08) | |

| Parental Intervention in School (std.) * Inattentive Behaviors Score (Parent) | 1.09 | 1.08 |

| (0.08) | (0.09) | |

| Parental School Intervention (std.) * Hyperactivity Behaviors Score (Parent) | 1.01 | 1.01 |

| Key Control Variables in Kindergarten | (0.06) | (0.07) |

| Child Reading Achievement Score (std.) | 1.09 | 1.00 |

| (0.08) | (0.09) | |

| Child Math Achievement Score (std.) | 0.73*** | 0.75** |

| (0.06) | (0.07) | |

| Middle-Class Family | 1.29* | 1.23 |

| (0.16) | (0.18) | |

| Upper-Class Family | 1.41* | 0.91 |

| (0.23) | (0.18) | |

| Black | 0.29*** | 0.33*** |

| (0.05) | (0.08) | |

| Hispanic | 0.34*** | 0.40*** |

| (0.06) | (0.09) | |

| Other Race/Ethnicity | 0.44*** | 0.57* |

| (0.08) | (0.14) | |

| School Fixed Effects | X | |

| N | 9750 | 5250 |

| Pseudo r-squared | 0.26 | 0.36 |

Displaying odds ratios. Robust standard errors in parentheses (standard errors clustered at the school level in model 1, which excludes fixed effects).

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001.

Models control for child pre-diagnosis math and reading scores, child oppositional defiant- or conduct disorder-related behaviors and internalizing behavior problems, the other parenting measures, family social class and demographic characteristics, classroom and early care context, and state and region characteristics (see Table 1 for detailed list).

Source: Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten Cohort of 1998–99.

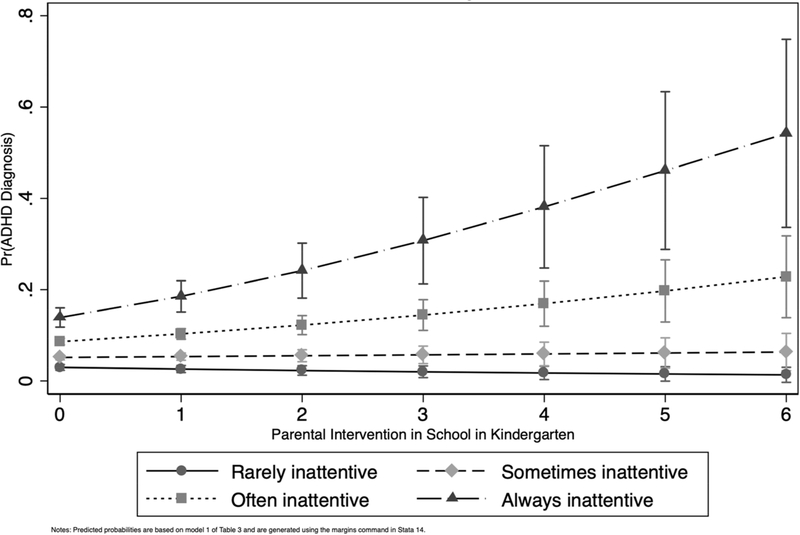

Given the complications with interpreting interaction terms in logit models (Long and Mustillo 2018), Figure 1 converts the 19% higher odds of diagnosis from model 1 of Table 3 into predicted probabilities at varying levels of parental intervention and pre-diagnosis teacher-rated inattention. Figure 1 focuses on teacher-rated inattention because of its statistically significant interaction with parental intervention in model 1. Among children with the least intervening parents, Figure 1 reveals that inattention is not significantly related to differences in the probability of diagnosis. However, the relationship between inattention and differences in probability of diagnosis become large and significant for children with the most intervening parents. For example, among children who are reported by teachers as “always” being inattentive, those whose parents have the highest level of intervention in school are on average 34 percentage-points more likely to be diagnosed than those whose parents are least intervening, net of differences in prior achievement, average classroom behavior, and the other child, family, and state level controls.

Figure 1.

Predicted Probabilities of ADHD Diagnosis at Differing Levels of Parental Intervention and Teacher-Rated Pre-Diagnosis Inattention Problems

3.4. Academic pressure as a moderator of the relationship between parental intervention and diagnosis

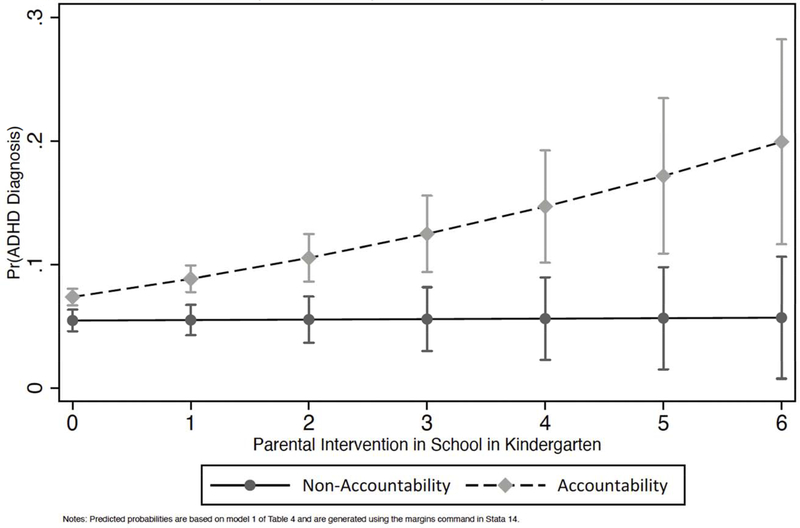

While prior work suggests that school-based accountability pressure to raise student test scores is a primary driver of diagnosis, accountability pressure may most strongly predict diagnosis among the children of intervening parents (hypothesis 3). Consistent with hypothesis 3, the multilevel random effects logit model 1 of Table 4 indicates that for children whose parents fall 1 SD increase above the mean on parental intervention in school, those in accountability states experience a statistically significant 30% higher odds of diagnosis (0.99*1.31).

Results from model 1 of Table 4 are presented as predicted probabilities in Figure 2. Figure 2 highlights that it is in contexts of high parental intervention in school that accountability-based academic pressure is associated with the highest predicted probabilities of diagnosis. For example, children living in accountability states with the highest level of parental intervention on average experience a roughly 15 percentage-point higher predicted probability of diagnosis than children also living in accountability states but whose parents have the lowest level of parental intervention.

Figure 2.

Predicted Probabilities of ADHD Diagnosis at Differing Levels of Parental Intervention and Exposure/Non-Exposure to Accountability-Based Academic Pressure

3.5. Alternative explanations for the relationship between parental intervention in school and ADHD diagnosis

There are two prominent alternative explanations that may account for the observed relationship between parental intervention in school and children’s ADHD diagnosis. First, the relationship may be driven by parents whose school intervention results from their child already receiving special education services in kindergarten and thus already being at risk for academic challenges. To test this possibility, I replicated analyses excluding the 350 sample children who were already receiving special education services in kindergarten. Results remain substantively similar, pointing away from this alternative explanation (see Appendix Table A.3, which also provides an example of estimates for the full set of controls included in all models).

Second, parental intervention in school might suffer from having the greatest potential for reverse association compared to other parenting measures because pre-existing parent and teacher concerns about child behaviors may result in increased parent-teacher interactions (i.e., parents may intervene in school more when they know their child requires extra attention from teachers). To examine this possibility, I separately regress each of the five parenting measures in kindergarten (outcomes) on child diagnosis with ADHD by the start of kindergarten, net of controls. Results indicate that childhood diagnosis with ADHD by the start of kindergarten is no more strongly associated with parental intervention in school in kindergarten than with the other measures of parenting. Thus, reverse association unique to direct parental intervention in school is unlikely to drive results (see Appendix Table A.4).

4. Discussion

The present study advances our understanding of the relationship between parents’ intervention in school and their children’s subsequent elementary school diagnoses of ADHD. This study’s focus on the role of parental intervention adds a new dimension to our understanding of the drivers of diagnosis within childhood disability research. Although ADHD as a disorder has significant impacts on children’s school and social functioning and development (Hinshaw and Scheffler 2014), the rapid rise in rates of childhood ADHD diagnoses in recent decades raises unresolved questions about the pathways to diagnosis and the conditions under which these pathways may be amplified or diminished. The present study shows that parents’ intervention in their children’s schools is one pathway that supports parents’ ability to seek out diagnoses for their children, to do so at the early signs of behavioral difficulties, and to do so particularly under contexts of academic pressure.

Methodologically, examining ADHD diagnosis unconditional on children’s referral for medical evaluation helps minimize bias due to non-random selection into evaluation. Analyses control for teacher and parent reports of children’s pre-diagnosis ADHD-related behaviors, prior academic achievement, a range of family, classroom and state characteristics, and school fixed effects in order to help guard against potential confounding from stable, unobserved differences between children—such as pre-existing academic or behavioral difficulties—that are correlated with parental school involvement and diagnosis. Drawing on population-level data from an initially nationally-representative sample of children followed longitudinally through elementary school offers a high degree of generalizability of findings.

This study uncovers three broad sets of findings. First, the study shows that parents’ intervention in school in kindergarten is positively associated with their children’s elementary school diagnoses of ADHD even among children attending the exact same schools. This finding appears to be specific to this particular form of direct school intervention, as other parenting behaviors—such as parents’ levels of cognitive stimulation, investment in child extracurricular activities, number of books at home, and educational expectations for the child—are not consistently significantly associated with diagnosis. In fact, the relationship between parental intervention and diagnoses persists even when holding constant these other forms of parental involvement, suggesting that there is something unique about parents’ intervention in school that is associated with diagnosis apart from other parenting behaviors and orientations.

Second, parental intervention in school is linked to ADHD diagnoses partly because intervening parents are also more likely to be able to be attentive to early signs of behavioral difficulties. The relationship between high levels of pre-diagnosis inattention problems and diagnosis is strongest for children whose parents have high levels of intervention in school: the children of parents who fall 1 SD above the mean on school intervention on average experience 19% higher odds of ADHD diagnosis for a 1 point increase above the mean on pre-diagnosis inattention problems and whose than those at the mean. This finding likely reflects the fact that inattention problems are more strongly related to children’s later academic achievement than are hyperactivity problems (Duncan et al. 2007). It suggests that intervening parents might be more aware of the importance of attention skills.

Third, the study provides evidence to help understand the conditions under which accountability-based academic pressure is most strongly associated with diagnosis among children from advantaged families (King, Jennings and Fletcher 2014). The findings are consistent with the idea that this relationship can arise because of high social class parents’ higher levels of intervention in their children’s schools. Moreover, the significant interaction uncovered between intervention and pre-diagnosis inattention problems suggests that the increased diagnoses among children of intervening parents in contexts of accountability-based academic pressure might reflect intervening parents’ increased sensitivity to their child’s behavioral problems.

This study also has a number of limitations and possible extensions. First, analyses are purely correlational given the lack of random assignment of parental intervention to families and families to states. For example, the accountability analysis assumes that certain states’ introduction of ‘pre-NCLB’ consequential accountability is uncorrelated with unobserved time period or cohort specific changes that could shape both entry into accountability and diagnosis (e.g., a neoliberal political turn in the state leading to both accountability and pharmaceutical advertising). Although models control for a wide range of observed state-level characteristics, the possibility of unobserved differences remains.

Second, key variables may contain measurement error. This study uses pre-diagnosis ADHD-related behavioral scales (and the internalizing and oppositional-defiant behavioral scales measuring commonly co-occurring behaviors) that measure frequency of behaviors. These scales do not capture other relevant factors, like behavioral intensity or duration, and also do not perfectly map on to DSM criteria. Unobserved clinical factors, if correlated with parental intervention/accountability and diagnosis, could lead to omitted-variables bias. Related, even though this study follows well-established precedent for identifying diagnosed children, there may be measurement error in the outcome due to reliance on parent reports of diagnosis by a medical professional.

Finally, this study’s findings are specific to the particular context and ages from which these data are drawn. This study focuses intentionally on the period of the late 1990s through the mid 2000s because of the meaningful variation that existed with respect to children’s exposure to school accountability policies amid a marked rise in ADHD diagnoses. This unique period offers insight into how social groups adapt to a rapidly changing social, medical, and educational landscape, such as changes in education policy.

Although results generalize only to this specific period, findings may offer enduring insights into the processes connecting families, schools, and the medicalization of children’s behavioral problems. To the extent that parents’ intervention in school has increased in recent decades, as recent work might suggest (Calarco 2018; Lareau 2011), current findings may underestimate the extent of these processes today.

5. Conclusion: Implications for Social Inequality

Understanding the relationship between parents’ intervention in school and children’s later diagnoses of ADHD is important because of its implications for socioeconomic and racial inequality. The present study’s findings connect important strands of prior work by empirically establishing a relationship between parental intervention in school and children’s diagnoses of ADHD. While the present study establishes a direct link between parental intervention in school and children’s later diagnoses of ADHD, prior work has established both social class and race differences in parents’ intervention in school (Calarco 2018; Lareau 2011; Lewis and Diamond 2015) and in the medicalization of children’s behavioral problems (King, Jennings and Fletcher 2014; Morgan and Farkas 2016; Morgan et al. 2013).

High social class and White parents are more likely than Black, Latino, and low social class parents to intervene in school to connect their children to the best teachers, to advanced track placement, to tutors, and to extra testing time (Calarco 2018; Lareau 2011; Lewis and Diamond 2015). The lower levels of intervention among Black and Latino and low social class parents do not reflect a lack of support for their children, but greater deference to teacher and school administrators’ authority in structuring their children’s schooling (Lewis and Diamond 2015). Some types of parental intervention may serve as forms of “opportunity hoarding,” or acting in ways that “cumulatively protect the advantages that privileged [typically White] kids receive from the way schooling is currently organized,” even if these behaviors are not explicit or obviously intended to exclude the less privileged (Lewis and Diamond 2015: 155).

Prior research likewise establishes important social class and race differences in the medicalization of children’s behavioral problems. One prior study finds that children from high social class families are roughly 30% more likely to strategically use ADHD medications during the academic year (presumably following an ADHD diagnosis) versus during the summer months than are children from low social class families (King, Jennings and Fletcher 2014). By contrast, some prior estimates suggest that Black and Latino children are significantly less likely to be identified, diagnosed, and/or treated for ADHD (Morgan and Farkas 2016; Morgan et al. 2013).

Taken together, parental intervention in school therefore may serve as an important condition driving these previously-identified relationships between social class, race, and ADHD diagnoses/treatment. That high social class and White parents are known to have greater levels of this type of intervention may therefore carry important implications for the production of inequality in children’s mental health and educational opportunities.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Parental school intervention is associated with increased childhood ADHD diagnoses

The relationship exists net of prior behavioral problems and academic achievement

The relationship exists among children attending the exact same schools

Intervening parents are typically more sensitive to children’s behavioral difficulties

They are also more sensitive to academic pressure from educational policies

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Jordan Conwell, Laura Doering, Anna Haskins, Daniel Hirschman, Margot Jackson, Zhenchao Qian, and David Rangel for invaluable feedback on this manuscript. This paper also benefited from presentations at the Population Association of America Annual Meeting in 2019 and the American Sociological Association Annual Meeting in 2019.

Footnotes

Notes

Some children in this sample may have been diagnosed with ADHD later in schooling or as adults. However, inclusion of these children as undiagnosed controls would downwardly bias (i.e., produce conservative) estimates of selection into diagnosis.

Although some of these 30 states did not adopt consequential accountability until after part way through this study’s diagnostic observation period from 1998–2003, their inclusion provides conservative (i.e., underestimates) of the relationship between accountability and ADHD diagnosis.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aizer Anna. 2008. “Peer Effects and Human Capital Accumulation: The Externalities of ADD.” NBER Working Paper no. w14354. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association Task Force. 1994. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV: Amer Psychiatric Pub Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Arcia Emily, Fernandez Maria C., Jaquez Marisela, Castillo Hector, and Ruiz Maria. 2004. “Modes of Entry Into Services for Young Children with Disruptive Behaviors.” Qualitative Health Research 14(9):1211–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchett Wanda J. 2010. “Telling It Like It Is: The Role of Race, Class, and Culture in the Perpetuation of Learning Disability as a Privileged Category for the White Middle Class.” Disability Studies Quarterly 30(2). [Google Scholar]

- Blum Linda M. 2015. Raising Generation Rx: Mothering Kids with Invisible Disabilities in an Age of Inequality. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bokhari Farasat A.S., and Schneider Helen. 2011. “School Accountability Laws and the Consumption of Psychostimulants.” Journal of Health Economics 30(2):355–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosco Jeffrey P., and Bona Anna. 2016. “Changes in Academic Demands and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Young Children.” JAMA Pediatrics 170(4):396–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calarco Jessica M. 2018. Negotiating Opportunities: How the Middle Class Secures Advantages in School: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. “Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder.” Cormier, Eileen. 2012. “How Parents Make Decisions to Use Medication to Treat their Child’s ADHD: A Grounded Theory Study.” Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association 18(6):345–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson Melissa L., Bitsko Rebecca H., Ghandour Reem M., Holbrook Joseph R., Kogan Michael D., and Blumberg Stephen J.. 2018. “Prevalence of Parent-Reported ADHD Diagnosis and Associated Treatment among U.S. Children and Adolescents, 2016.” Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 47(2):199–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dee Thomas S., and Jacob Brian. 2011. “The Impact of No Child Left Behind on Student Achievement.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 30(3):418–46. [Google Scholar]

- Dey AN, Schiller JS, and Tai DA. 2004. “Summary Health Statistics for U.S. Children: National Health Interview Survey, 2002.” Pp. Page 18: Table3. in Vital Health Statistics, edited by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Washington, DC: National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan Greg J., Dowsett Chantelle J., Claessens Amy, Magnuson Katherine, Huston Aletha C., Klebanov Pamela, Pagani Linda S., Feinstein Leon, Engel Mimi, and Brooks-Gunn Jeanne. 2007. “School Readiness and Later Achievement.” Developmental psychology 43(6):1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figlio David, and Loeb Susanna. 2011. “Chapter 8 - School Accountability.” Pp. 383–421 in Handbook of the Economics of Education, edited by Hanushek Eric A., Machin Stephen, and Woessmann Ludger: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Gius Mark P. 2007. “The Impact of the Americans with Disabilities Act on Per-Student Public Education Expenditures at the State Level: 1987–2000.” American Journal of Economics and Sociology 66(5):925–36. [Google Scholar]

- Harry Beth, and Klingner Janette. 2007. “Discarding the Deficit Model.” Educational Leadership 64(5):16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw Stephen P., and Scheffler Richard M.. 2014. The ADHD Explosion: Myths, Medication, Money, and Today’s Push for Performance: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Horvat Erin McNamara, Weininger Elliot B., and Lareau Annette. 2003. “From Social Ties to Social Capital: Class Differences in the Relations Between Schools and Parent Networks.” American Educational Research Journal 40(2):319–51. [Google Scholar]

- King Marissa D., Jennings Jennifer, and Fletcher Jason M.. 2014. “Medical Adaptation to Academic Pressure: Schooling, Stimulant Use, and Socioeconomic Status.” American Sociological Review 79(6):1039–66. [Google Scholar]

- Koretz Daniel M. 2008. Measuring Up. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lareau Annette. 2011. Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis Amanda E., and Diamond John B.. 2015. Despite the Best Intentions: How Racial Inequality Thrives in Good Schools. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Long J. Scott, and Mustillo Sarah A.. 2018. “Using Predictions and Marginal Effects to Compare Groups in Regression Models for Binary Outcomes.” Sociological Methods & Research OnlineFirst:1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Mittleman Joel, and Jennings Jennifer L.. 2018. “Accountability, Achievement, and Inequality in American Public Schools: A Review of the Literature.” Pp. 475–92 in Handbook of the Sociology of Education in the 21st Century, edited by Schneider Barbara. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan Paul L., and Farkas George. 2016. “Evidence and Implications of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Emotional and Behavioral Disorders Identification and Treatment.” Behavioral Disorders 41(2):122–31. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan Paul L., Staff Jeremy, Hillemeier Marianne M., Farkas George, and Maczuga Steven. 2013. “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in ADHD Diagnosis from Kindergarten to Eighth Grade.” Pediatrics 132(1):85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrill Melinda Sandler. 2018. “Special Education Financing and ADHD Medications: A Bitter Pill to Swallow.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 37(2):384–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong-Dean Colin. 2009. Distinguishing Disability: Parents, Privilege, and Special Education: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Owens Jayanti. 2020. “Social Class, Diagnoses of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, and Child Well-Being.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 61(2):134–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell Jennifer L. 2011. “From Child’s Garden to Academic Press: The Role of Shifting Institutional Logics in Redefining Kindergarten Education.” American Educational Research Journal 48(2):236–67. [Google Scholar]

- Sax Leonard, and Kautz Kathleen J.. 2003. “Who First Suggests the Diagnosis of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder?” The Annals of Family Medicine 1(3):171–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider Helen, and Eisenberg Daniel. 2006. “Who Receives A Diagnosis of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in the United States Elementary School Population?” Pediatrics 117(4):e601–e09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shifrer Dara. 2018. “Clarifying the Social Roots of the Disproportionate Classification of Racial Minorities and Males with Learning Disabilities.” The Sociological Quarterly 59(3):384–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shifrer Dara, and Fish Rachel. 2020. “A Multilevel Investigation into Contextual Reliability in the Designation of Cognitive Health Conditions among U.S. Children.” Society and Mental Health 10(2):180–97. [Google Scholar]

- Sleeter Christine. 2010. “Why is there Learning Disabilities? A Critical Analysis of the Birth of the Field in its Social Context.” Disability Studies Quarterly 30(2). [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. Elizabeth, and Farah Martha J.. 2011. “Are Prescription Stimulants “Smart Pills”? The Epidemiology and Cognitive Neuroscience of Prescription Stimulant Use by Normal Healthy Individuals.” Psychological Bulletin 137(5):717–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson James, Baler Ruben D., and Volkow Nora D.. 2010. “Understanding the Effects of Stimulant Medications on Cognition in Individuals with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Decade of Progress.” Neuropsychopharmacology 36(1):207–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau Karen, Nord Christine, Lê Thanh, Sorongon Alberto G., and Najarian Michelle. 2009. “Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 1998–99 (ECLS-K): Combined Users Manual for the ECLS-K Eighth-Grade and K-8 Full Sample Data Files and Electronic Codebooks. NCES; 2009–004.” [Google Scholar]

- Von Hippel Paul T. 2007. “Regression with Missing Ys: An Improved Strategy for Analyzing Multiply Imputed Data.” Sociological Methodology 37(1):83–117. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Guifeng, Strathearn Lane, Liu Buyun, Yang Binrang, and Bao Wei. 2018. “Twenty-Year Trends in Diagnosed Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder among US Children and Adolescents, 1997–2016.” JAMA network open 1(4):e181471–e71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.