Abstract

Single agents have demonstrated activity in relapsed and refractory (R/R) peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL). Their benefit relative to combination chemotherapy remains undefined. Patients with histologically confirmed PTCL were enrolled in the Comprehensive Oncology Measures for Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma Treatment (COMPLETE) registry. Eligibility criteria included those with R/R disease who had received one prior systemic therapy and were given either a single agent or combination chemotherapy as first retreatment. Treatment results for those with R/R disease who received single agents were compared to those who received combination chemotherapy. The primary endpoint was best response to retreatment. Fifty-seven patients met eligibility criteria. At first retreatment, 46% (26/57) received combination therapy and 54.5% (31/57) received single agents. At median follow up of 2 years, a trend was seen towards increased complete response rate for single agents versus combination therapy (41% vs 19%; P = .02). There was also increased median overall survival (38.9 vs 17.1 months; P = .02) and progression-free survival (11.2 vs 6.7 months; P = .02). More patients receiving single agents received hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (25.8% vs 7.7%, P = .07). Adverse events of grade 3 or 4 occurred more frequently in those receiving combination therapy, although this was not statistically significant. The data confirm the unmet need for better treatment in R/R PTCL. Despite a small sample, the analysis shows greater response and survival in those treated with single agents as first retreatment in R/R setting, while maintaining the ability to achieve transplantation. Large, randomized trials are needed to identify the best strategy.

1 |. INTRODUCTION

The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of mature T and NK neoplasms now includes 27 distinct entities.1 Of these entities, three major subtypes, peripheral T-cell lymphoma-not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS), angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), and anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), known asnodal PTCL, account for approximately 60% of all cases.2 Despite their heterogeneity, the vast majority of PTCLs are treated similarly, and are characterized by aggressive clinical behavior and dismal outcomes.3

In the upfront setting, most fit patients with PTCL undergo induction with anthracycline-based chemotherapy followed by hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT) in first remission, as multiple groups have shown encouraging results with this approach.3 While randomized trial data is lacking, two large retrospective series can provide expectations for response and survival for those who receive upfront anthracycline-based therapy. The British Columbia Cancer Agency (BCCA), for a series of 199 cases between 1980 and 2000, reported objective response rates for PTCL-NOS, AITL, and ALCL of 84%, 90%, and 76%, respectively.4 Most patients in this series received upfront anthracycline-based therapy. Despite these response rates, 5-year progression-free survival rates for PTCL-NOS, AITL, and ALCL were 29%, 28%, and 36%, respectively, highlighting the high rates of relapse. Similarly, the International T-Cell Lymphoma Project (ITCP), for 1314 cases between 1990 and 2002, reported 5-year failure-free survival rates for PTCL-NOS, AITL, anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-negative ALCL and ALK-positive ALCL of 20%, 18%, 36%, and 60%, respectively.5 In addition to those who relapsed, the ITCP reported 47% of patients had primary refractory disease.6 These data show the large number of patients who need treatment in the relapsed and refractory (R/R) setting, and underscore the urgency for improved salvage therapies.

There is no standard approach to the treatment of patients with R/R PTCL. The current recommendation by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network for fit patients is involvement in a clinical trial.7 Outside of a clinical trial, the majority of fit patients will receive non-overlapping second-line combination chemotherapy. The goal is inducing a complete remission and achieving an HSCT, which remains the only reliable curative approach.8 However, outcomes using this strategy have been poor. In the BCCA, median overall survival for patients with R/R disease, most of whom received traditional combination chemotherapy, was 6.5 months.4 In the ITCP, median overall survival for those with R/R disease was 5.8 months.5 In the Modeno Cancer Registry, a series of 53 patients with R/R PTCL between 1997 and 2010, overall survival after relapse was 2.5 months.9

The last decade has seen the approval of several novel, single agents for patients with R/R PTCL. These agents include antifolates such as pralatrexate, histone deacetylase inhibitors such as romidepsin and belinostat, and the CD30-targeted antibody-drug conjugate, brentuximab vedotin. Brentuximab vedotin has demonstrated a striking effect in the R/R setting, with objective response rates of 86% in ALCL and 41% in CD30-expressing T-cell lymphomas leading to its evaluation for upfront treatment of CD30+ PTCL patients.10,11 Recent results from the phase 3 randomized, double-blind ECHELON-2 study compared the efficacy and safety of standard CHOP with an alternative regimen containing brentuximab (A plus CHP). The study of frontline treatment of systemic ALCL and other CD30-expressing PTCL, demonstrated a remarkable improvement in median progression-free survival with integration of brentuximab plus traditional chemotherapy over CHOP alone (48.2 months versus 20.8 months). Ithas potentially changed the frontline treatment paradigm for CD30-expressing PTCL patients.12 Pralatrexate, romidepsin, and belinostat are able to induce objective responses ranging from 23% to 38% in R/R PTCL, with some patients achieving durable remissions.13–17

Additional anti-lymphoma agents, including alisertib, bendamustine, and lenalidomide, have demonstrated modest activity in R/R PTCL and are often used for salvage after failure of antifolates and histone deacetylase inhibitors.18–22 The favorable side-effect profile of these single agents, and the ability to administer them in the outpatient setting as a potential long-term, continuous treatment, makes these drugs an attractive option for many patients. As such, these agents have begun to challenge the role of traditional intensive combination regimens. The BCCA, ITCP and Modeno Cancer Registries do not reflect the increasing use of these recently approved single agents for R/R PTCL, and an updated analysis is needed.

The present study aims to better understand whether these novel, single agents can improve outcomes of patients with R/R PTCL in comparison to conventional multiagent chemotherapy. Treatment outcomes of single agents are compared to traditional, combination chemotherapy, in the largest prospectively enrolled cohort of newly-diagnosed PTCL patients in the United States.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Study design and eligibility

The Comprehensive Oncology Measures for Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma Treatment (COMPLETE) registry is a multicenter prospective observational study of newly diagnosed PTCL patients in the United States. Patients were eligible for enrollment in COMPLETE if they provided written informed consent and had a new diagnosis of histologically confirmed PTCL. Patients for whom initial treatment was ≤4 days, unreported, or began >30 days before or after informed consent were excluded. All subtypes of PTCL were included with the exception of precursor T/NK neoplasms, T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia, mycosis fungoides other than transformed mycosis fungoides, Sézary syndrome, and primary cutaneous CD30+ disorders. Patients participating in clinical trials were not excluded.

2.2 |. Definitions

In our analysis, primary refractory was defined as a lack of a complete response to initial treatment. Relapsed was defined as a complete response to initial treatment with progression at a later date. Eligible patients for our analysis were those with primary refractory or relapsed disease that had received only one prior systemic therapy with or without HSCT. Our analysis was restricted to six common subtypes of PTCL: PTCL-NOS, AITL, ALCL, enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL), natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (NKT), and hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma (HSTCL). Patients were included in the single agent arm if at first retreatment they received any of the following single agents: pralatrexate, romidepsin, belinostat, brentuximab vedotin, bendamustine, alisertib, denileukin diftitox, or lenalidomide. Patients were included in the combination arm if at first retreatment they received any multiagent chemotherapy regimen excluding the above single agents.

2.3 |. Data collection

Data collection for COMPLETE has been described elsewhere.23 In brief, de-identified data were regularly uploaded onto the study server from each enrolling site by the treating physician. Data were subjected to automated error checking that searched for logical inconsistencies, out of range values, and missing data. Data was locked after either the treating physician or site principal investigator performed verification of accuracy. A further review of the locked data then occurred within the central committee, a collection of experts in PTCL. Histological data entered at each site was separately verified by five independent hematopathologists to ensure accuracy via comparison of uploaded histologic data to the diagnostic pathology reports.24

2.4 |. Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the best reported response to first retreatment therapy, which was classified as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), progressive disease, or not evaluable. All recorded responses were investigator responses. Secondary end points included progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), ability to bridge to transplantation, and adverse events of grade 3 or 4. Response and survival definitions were in accordance with the International Workshop Criteria guidelines for response assessments for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas.25 Adverse events were defined and graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events.26

2.5 |. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis for COMPLETE has been described elsewhere.23 In brief; descriptive statistics were used to summarize the baseline characteristics of the study cohort. For categorical and ordinal variables, frequencies and percentages were calculated. For continuous variables, the number of patients, means, medians, standard deviations and ranges were provided. Null hypothesis testing utilized chi-square, t-test and other non-parametric tests as required, with a two-tailed P value of ≤.05 used to reject the null hypothesis. Survival-based analyses were performed using Kaplan-Meier methodology, with censoring as appropriate, and evaluated with a log rank test with a two-tailed P value of ≤.05 to reject the null hypothesis. All analyses were performed using R version 3.1.0 or greater (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing - http://www.r-project.org/).

2.6 |. Sensitivity analysis

Based on preliminary results, and given the known high response rates of PTCL to brentuximab vedotin (BV), especially in patients with ALCL (57% CR and 86% ORR in the original phase II trial of BV in ALCL10 data here more appropriate to results section), we sought to determine whether any favorable results from the single agent arm were solely driven by patients treated with BV. To do this, we performed a subgroup analysis in which all patients who received BV at first retreatment were excluded from the single agent arm and were grouped to form a separate cohort (Single-BV). This cohort was then compared against the single agent arm excluding those treated with BV (Single-Other), and the original combination therapy arm, with the same endpoints as described above.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Patient characteristics

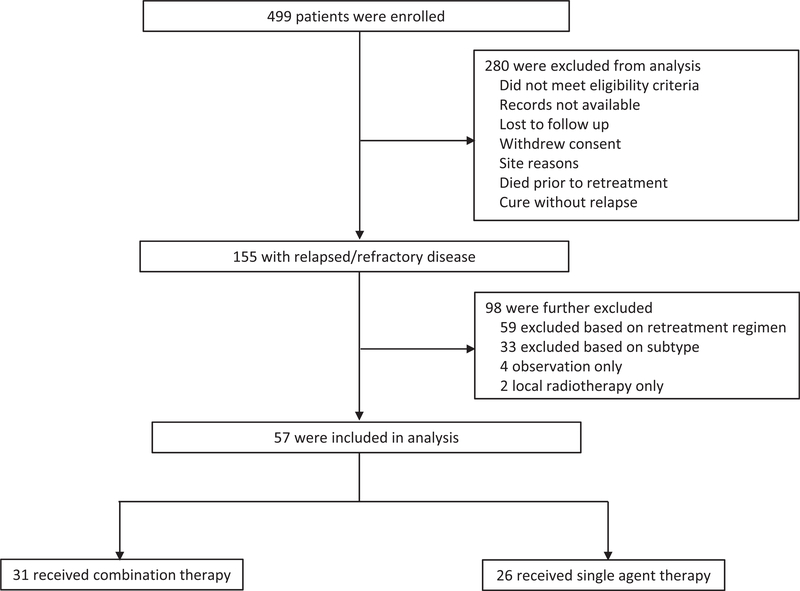

A total of 499 patients were enrolled in COMPLETE between 2010 and 2014 from 56 academic and community centers. Baseline demographic characteristics of patients enrolled in COMPLETE have been reported previously and are comparable to the patients from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program.5 A total of 57 patients (11.4%) met the above eligibility criteria of having R/R disease with one of the aforementioned subtypes. They alsoreceived first retreatment with either single (n = 26) or combination (n = 31) therapy as defined above (Figure 1). Sixteen patients (61.5%) in the combination group and seven patients (22.5%) in the single agent group had primary refractory disease, respectively. Conversely, ten patients (38.5%) in the combination group and 24 patients (77%) in the single agent group had relapsed disease, respectively.

FIGURE 1.

Eligibility criteria of the study population. A total of 499 pateints were enrolled in COMPLETE Registry. Patients were initially excluded if they did not meet eligibility criteria, defined as having a known duration of initial treatment, starting treatment less than 30 days before or after consent, and having greater than or equal to 5 days of initial treatment. Patients were also excluded if they had records that were not available, were lost to follow-up, withdrew consent, had issues related to their site of enrollment, died prior to retreatment, or were cured with upfront therapy. This resulted in 155 patients with relapsed or refractory disease available for analysis. Patients were further excluded if they had a disease subtype other than what was included in our analysis (PTCL-NOS, AITL, ALCL, EATL, NKT, HSTCL). Patients were also excluded if treated with a regimen other than combination cytotoxic therapy, or a single agent (alisertib, bendamustine, brentuximab vedotin, denileukin diftitox, lenalidomide, pralatrexate, romidepsin), or received only radiotherapy or observation. Much of the material in the figure legends does not belong in them; it is information for the results section, especially median overall survival. AITL, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; ALCL, anaplastic large cell; EATL, enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma; HSTCL, hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma; NKT, natural killer/T-cell lymphoma; PTCL-NOS, peripheral T-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified

The baseline demographic, performance status, and histopathologic characteristics of the patients included in our analysis are shown in Table 1. Patients who received single agents were significantly older than those who received combination therapy (63.4 years vs 50.8 years; P < .01). Other demographic characteristics were well balanced across treatment groups. In both treatment groups, the mean Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PFS) was 0–1 and the mean International Prognostic Index (IPI) was 2. In the combination therapy group, the mean Prognostic Index for PTCL (PIT) score was 1–2, and in the single agent group, the mean PIT score was 2. There were no significant differences between treatment groups in choice of first retreatment based on histological subtype, though all seven patients with ALK-negative ALCL received single agents, and all three patients with ALK-positive ALCL received combination therapy.

TABLE 1.

Demographics performance status, and histopathological characteristics at baseline

| Total (%) | Combination (26) | Single (31) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) ± SD | 50.8 ± 14.9 | 63.4 ± 13.1 | .0014 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 19/57 (33.3) | 6/26 (23.1) | 13/31 (41.9) | .1325 |

| Male | 38/57 (66.7) | 20/26 (76.9) | 18/31 (58.1) | |

| ECOG performance status | ||||

| 0–1 | 53/57 (93.0) | 24/26 (92.3) | 29/31 (93.5) | .8551 |

| 2 | 4/57 (7.0) | 2/26 (7.7) | 2/31(6.5) | |

| Number of extranodal sites | ||||

| <2 | 12/32 (37.5) | 7/15 (46.7) | 5/17(29.4) | .3144 |

| 2 or more align | 20/32 (62.5) | 8/15 (53.3) | 12/17 (70.6) | |

| Serum LDH elevated lU/ml | 24/57 (42.1) | 10/26 (38.5) | 14/31 (45.2) | .6099 |

| IPI: | ||||

| 0 | 3/57 (5.3) | 2/26 (7.7) | 1/31(3.2) | .3826 |

| 1 | 12/57 (21.1) | 6/26 (23.1) | 6/31(19.4) | |

| 2 | 22/57 (38.6) | 11/26 (42.3) | 11/31 (35.5) | |

| 3 | 16/57 (28.1) | 7/26 (26.9) | 9/31(29.0) | |

| 4 | 4/57 (7.0) | 0/26 (0.0) | 4/31(12.9) | |

| PIT score | ||||

| Group 1 | 14/57 (24.6) | 9/26 (34.6) | 5/31(16.1) | .1728 |

| Group 2 | 24/57 (42.1) | 9/26 (34.6) | 15/31 (48.4) | |

| Group 3 | 13/57 (22.8) | 7/26 (26.9) | 6/31(19.4) | |

| Group 4 | 6/57 (10.5) | 1/26 (3.8) | 5/31(16.1) | |

| Histo pathology | ||||

| ALCL-ALK− | 7/57 (12.3) | 0/26 (0.0) | 7/31 (22.6) | .0600 |

| ALCL-ALK+ | 3/57 (5.3) | 3/26(11.5) | 0/31 (0.0) | |

| AITL | 11/57 (19.3) | 6/26 (23.1) | 5/31(16.1) | |

| EATL | 3/57 (5.3) | 1/26 (3.8) | 2/31(6.5) | |

| HSTL | 3/57 (5.3) | 1/26 (3.8) | 2/31(6.5) | |

| PTCL-NOS | 22/57 (38.6) | 10/26 (38.5) | 13/31 (41.9) | |

| T/NK | 7/57 (12.3) | 5/26 (19.2) | 2/31(6.5) | |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; AITL, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; ALCL-ALK+, anaplastic large cell-anaplastic lymphoma kinase positive; ALCL-ALK-, anaplastic large cell lymphoma-anaplastic lymphoma kinase negative; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EATL, enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma; HSTL, hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma; IPI, International Prognostic Index; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PIT, Prognostic Index for T-cell lymphoma; PTCL-NOS, peripheral T-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified; T/NK, t-cell natural killer lymphoma.

3.2 |. Initial treatment and outcomes

Details of upfront treatment are shown in (Table S1). The majority of patients receiving upfront therapy were treated with curative intent (89.5%). Sixty-eight percent (39/57) of patients received induction chemotherapy alone, and 21.1% (12/57) received induction chemotherapy plus autologous HSCT. The types of regimens that were used in the upfront setting are included in Table S2. A greater number of patients in the single agent group achieved an initial CR versus those in the combination therapy (77.4% vs 38.5%; P = .02). Consequently, a greater number of patients in the singe agent group received HSCT versus those in the combination group (32.3% vs 7.7%; P = .02). Mean PFS was 9.2 months and was greater in the single agent group versus the combination group (11 months vs 5.1 months; P = .06).

For patients in the upfront setting in whom transplantation did not occur, it was not considered or considered but not completed. For those in whom it was not considered, reasons included physician choice (45.5%), patient age and comorbidities (22.7%), PTCL subtype (18.2%), patient choice (9.1%), cost/insurance (9.1%), or other reasons (31.8%). For those in whom transplantation was considered but not completed, reasons included progressive disease (45.5%), inability to mobilize cells (9.1%), patient choice (9.1%), lack of donor (9.1%) or other reasons (27.3%).

3.3 |. First retreatment

The regimens used at first retreatment are shown in Table S3. At first retreatment, 26 patients (45.6%) received combination therapy and 31 patients (54.4%) received single agent therapy. The most common combination regimens had a gemcitabine- (38.5%), ifosfamide- (26.9%), or platinum-based (15.54%) backbone. The most frequently used single agents were brentuximab vedotin (38.7%), romidepsin (22.6%) and pralatrexate (16.1%).

3.4 |. Outcomes of first retreatment

Median follow-up time from diagnosis of relapse or refractory was 731.5 days. Table 2 shows outcomes in the R/R setting. At first retreatment, 70.2% of patients were treated with curative intent as reported by the treating physician, though a statistically significant greater number of patients who received combination therapy versus single agents were treated with curative intent (84.6% vs 58.1%; P = .03). As for response, the CR rate was statistically significantly greater for single agents than for combination therapy (41% vs 19%; P = .02). A CR was achieved with use of the following single agents: brentuximab vedotin (7), romidepsin (2), pralatrexate (1), alisertib (1), bendamustine (1). Those being treated with single agents received a significantly greater number of cycles (4.8 vs 2.4; P = .02) and remained on treatment longer (3.3 months vs 1.5 months; P = .06). There were no significant differences in response rates by stage or IPI score.

TABLE 2.

Retreatment intent, best response, and duration of therapy

| Total (%) | Combination | Single | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary intent | ||||

| Cure | 40/57 (70.2) | 22/26 (84.6) | 18/31 (58.1) | .0291 |

| Palliative | 17/57 (29.8) | 4/26 (15.4) | 13/31 (41.9) | |

| Mean number of cycles ± SD | 3.8 ± 3.7 | 2.7 ± 1.7 | 4.8 ± 4.6 | .0206 |

| Best response | ||||

| Complete | 17/55 (30.9) | 5/26 (19.2) | 12/29 (41.4) | .0195 |

| Partial | 12/55 (21.8) | 7/26 (26.9) | 5/29 (17.2) | |

| None | 9/55 (16.4) | 8/26 (30.8) | 1/29 (3.4) | |

| Progressive | 12/55 (21.8) | 3/26(11.5) | 9/29 (31.0) | |

| Not evaluable | 5/55 (9.1) | 3/26(11.5) | 2/29 (6.9) | |

| Mean duration of treatment (months) ± SD | 2.5 ±3.1 | 1.5 ± 1.2 | 3.3 ± 3.9 | .0648 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

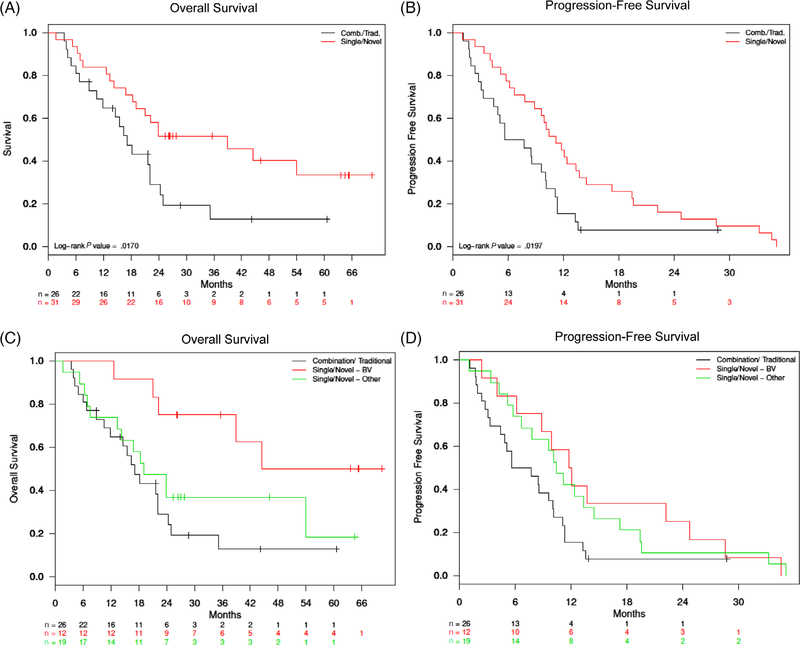

Median OS was statistically significantly greater for those receiving single agents than in those receiving combination therapy (38.9 months vs 17.1 months, P = .02), as was PFS (11.2 months vs 6.7 months, P = .02) (Figure 2A,B). There were no significant differences in survival by the stage or IPI score.

FIGURE 2.

Overall survival and progression-free survival after first retreatment including sensitivity analysis. A, The red line indicates survival for those who received a single agent as first retreatment. The black line indicates survival for those who received combination therapy as first retreatment. The median overall survival was 38.9 months in the single agent group, as compared to 17.1 months in the combination therapy group. B, The median progression-free survival was 11.2 months in the single agent group, as compared to 6.7 in the combination therapy group. C, The red line indicates survival for those who received brentuximab vedotin as first retreatment. The green line indicates survival for those who received a single agent other than brentuximab vedotin as first retreatment. The black line indicates survival for those who received combination therapy as first retreatment. The median overall survival was 44.5 months for those who received brentuximab vedotin as first retreatment, as compared to 19.1 months for those who received a single agent other than brentuximab vedotin, and 17.1 months for those who received combination therapy. D, The median progression-free survival was 11.9 months for those who received brentuximab vedotin as first retreatment, as compared to 10.4 months for those who received single agent other than brentuximab vedotin, and 6.7 months for those who received combination therapy

3.5 |. Transplantation outcomes

Transplantation occurred more frequently in those receiving single agents than in those receiving combination therapy (25.8% vs 7.7%; P = .07) (Table S4?). Two patients in the combination group received HSCT, both of which were autologous. Eight patients in the single agent group received HSCT, four of which were autologous and four of which were allogeneic. Of the two patients in the combination therapy group who received HSCT, one achieved a CR post-transplant and one achieved a PR. Of the eight patients in the single agent group who received HSCT, four achieved a CR post-transplant, three achieved a PR, and one had progressive disease. After a median follow-up of 27 months, nine out of the ten patients (90.0%) who received a transplant were alive.

3.6 |. Toxicity profiles

Overall, 71.9% of patients experienced an adverse event of grade 3 or 4 (Table S5). Adverse events of grade 3 or 4 occurred more frequently in the combination group versus the single agent group (80.8% vs 64.5%; P = .17) although this was not statistically different. Those receiving combination therapy generally had increased requirements for supportive care measures, significantly more so for the receipt of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (61.5% vs 25.8%, P < .01).

3.7 |. Sensitivity analysis

Given the significantly high response rates and durable remissions induced by brentuximab vedotin (BV), especially in patients with R/R systemic ALCL, we sought to determine whether the above results demonstrating efficacy of single agents over combination therapy were solely driven by those who had received brentuximab vedotin. Therefore, we performed a sensitivity analysis as described above, the results of which are shown (Table S6). A total of 12 patients received BV (Single-BV): six patients with ALK-negative ALCL (50.0%), 5 patients with PTCL-NOS (41.7%), and 1 patient with NKT (8.3%). The Single-Other cohort was defined as all patients who received a single agent other than BV as first retreatment. The CR rate in the Single-BV group was 58.3% (7/12), compared with 29.4% in the Single-Other group, and 19.2% in the combination therapy group still (P = .06). Median OS for the Single-BV group was 44.5 months, compared with 19.1 months for the Single-Other group and 17.1 months for the combination therapy group (Figure 2C). PFS was similar between the Single-BV and Single-Other group (11.9 vs 10.4 months), and both were greater than that of the combination therapy group (6.7 months) (Figure 2D).

4 |. DISCUSSION

This is the first prospective study detailing the use of single agents and combination therapy in patients with PTCL, in the primary refractory or relapsed setting. The COMPLETE registry represents the largest multi-institutional, prospectively collected PTCL database to date in the United States. Itincludes clinically pertinent data, such as performance status, histopathologic subtypes, pertinent laboratory studies, and treatment histories. Although databases exist from the phase II registration studies of the FDA-approved single agents, patients in these registries were predominantly treated at academic centers. The patientshad to meet strict eligibility criteria, thus not fully reflecting the ‘real-world’ outcomes that are captured in this diverse registry.

Our study confirms the unmet need for better therapies in R/R PTCL. The current NCCN guidelines do not provide any definitive recommendations for the treatment of relapsed and refractory patients. Therefore practices are subject to physician bias and vary widely across treatment settings. Our analysis shows a trend towards greater complete and objective response rates with the use of single agents versus combination chemotherapy, as well as a statistically significant greater overall and progression-free survival. In addition, more patients receiving single agents were bridged to potentially curative transplantation. More toxicity occurred with the use of combination chemotherapy, as did the need for supportive care measures.

It is unclear what factors were driving the differences in survival between single agent and combination therapy. One possibility is the ability for those in the single agent group to have longer treatment duration owing to less toxicity, fewer hospitalizations, and less need for supportive measures. A second possibility is the potential role of brentuximab vedotin in the non-ALCL patients who received it. Third, more patients treated with single agents achieved transplantation. It is possible that the observed increases in survival were driven by the extended survival of those who were transplanted, as previous reports have shown survival benefits with transplantation.27,28

A major limitation to our study is the small sample size, which allowed for the enrichment of patients who received a highly active, targeted agent in brentuximab vedotin. Although our sensitivity analysis still demonstrated benefit from single agents after excluding these patients. The small sample size is vulnerable to confounding from unmeasured variables (variable such as physician and patient preferences and unintentional) and unintentional selection bias, both of which are expected drawbacks of our nonrandomized design.

In conclusion, we demonstrate a role for single agents as the first treatment in the salvage setting for patients with R/R PTCL. The optimal approach in this setting remains unclear, and this report should serve as a catalyst for future studies utilizing larger datasets or randomized designs to identify the truly superior strategy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding information

Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Schwartz: (employment); Acosta: Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (employment); Pro: Takeda Pharmaceutical Company (honoraria), Portola Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (honoraria), Seattle Genetics (consultancy, research funding), Kyowa Kirin Pharmaceutical Development, Inc. (honoraria); Shustov: Seattle Genetics (research funding); Horwitz: Aileron Therapeutics (consultancy, research funding), Takeda Pharmaceutical Company (consultancy, research funding), Mundipharma (consultancy), ADC Therapeutics (consultancy, research funding), Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (research funding), Trillium Therapeutics, Inc. (consultancy), Corvus Pharmaceuticals (consultancy), Forty Seven, Inc. (consultancy, research funding), Seattle Genetics (consultancy, research funding), Celgene (consultancy, research funding), Innate Pharma (consultancy), Infinity Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (consultancy, research funding), Verastem Oncology (consultancy, research funding); Portola Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (consultancy), Kyowa Kirin Pharmaceutical Development, Inc. (consultancy, research funding); Foss: Seattle Genetics (consultancy), Miragen Therapeutics, Inc. (consultancy, speakers bureau), Mallinkrodt (consultancy), Spectru Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (consultancy).

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood 2016;127(20):2375–2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vose JM. Peripheral T-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am 2008;22(5):997–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moskowitz AJ, Lunning MA, Horwitz SM. How I treat the peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Blood 2014;123(17):2636–2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savage KJ, Chhanabhai M, Gascoyne RD, et al. Characterization of peripheral T-cell lymphomas in a single North American institution by the WHO classification. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol 2004; 15(10):1467–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vose J, Armitage J, Weisenburger D. International T-Cell lymphoma project. international eripheral T-Cell and natural killer/T-Cell lymphoma tudy: pathology findings and clinical outcomes. J. Clin. Oncol 2008;26(25):4124–4130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellei M, Foss FM, Shustov AR, et al. The outcome of peripheral T-cell lymphoma patients failing first-line therapy: a report from the prospective, international T-Cell project. Haematologica 2018;103(7): 1191–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: T-Cell Lymphomas, Version 5.2018 2018. Not proper format. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lunning MA, Moskowitz AJ, Horwitz S. Strategies for relapsed peripheral T-cell lymphoma: the tail that wags the curve. J. Clin. Oncol 2013; 31(16):1922–1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biasoli I, Cesaretti M, Bellei M, et al. Dismal outcome of T-cell lymphoma patients failing first-line treatment: results of a population-based study from the Modena Cancer Registry. Hematol. Oncol 2015; 33(3):147–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pro B, Advani R, Brice P, et al. Brentuximab vedotin (SGN-35) in patients with relapsed or refractory systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: Results of a phase II study. J. Clin. Oncol 2012;30(18): 2190–2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horwitz SM, Advani RH, Bartlett NL, et al. Objective responses in relapsed T-cell lymphomas with single-agent brentuximab vedotin. Blood 2014;123(20):3095–3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horwitz SM, O’Connor OA, Pro B, et al. Brentuximab vedotin with chemotherapy for CD30-positive peripheral T-cell lymphoma (ECHELON-2): a global, double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019;393(10168):229–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Connor OA, Pro B, Pinter-Brown L, et al. Pralatrexate in patients with relapsed or refractory peripheral T-Cell lymphoma: results from the pivotal PROPEL study. J. Clin. Oncol 2011;29(9): 1182–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piekarz RL, Frye R, Prince HM, et al. Phase 2 trial of romidepsin in patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Blood 2011;117(22): 5827–5834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coiffier B, Pro B, Prince HM, et al. Results from a pivotal, open-label, phase II study of romidepsin in relapsed or rperipheral T-cell lymphoma after prior systemic therapy. J. Clin. Oncol 2012;30(6): 631–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foss F, Advani R, Duvic M, et al. A phase II trial of belinostat (PXD101) in patients with relapsed or refractory peripheral or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol 2015;168(6): 811–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Connor OA, Horwitz S, Masszi T, et al. Belinostat in patients with relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma: results of the pivotal phase II BELIEF (CLN-19) Study. J. Clin. Oncol 2015;33(23): 2492–2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Damaj G, Gressin R, Bouabdallah K, et al. Results from a prospective, open-label, phase II trial of bendamustine in refractory or relapsed T-cell lymphomas: The BENTLY trial. J. Clin. Oncol 2013;31(1): 104–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zinzani PL, Pellegrini C, Broccoli A, et al. Lenalidomide monotherapy for relapsed/refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified. Leuk. Lymphoma 2011;52(8):1585–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morschhauser F, Fitoussi O, Haioun C, et al. A phase 2, multicentre, single-arm, open-label study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of single-agent lenalidomide (Revlimid) in subjects with relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the EXPECT trial. Eur. J. Cancer 2013;49(13):2869–2876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toumishey E, Prasad A, Dueck G, et al. Final report of a phase 2 clinical trial of lenalidomide monotherapy for patients with T-cell lymphoma. Cancer 2015;121(5):716–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barr PM, Li H, Spier C, et al. Phase II intergroup trial of alisertib in relapsed and refractory peripheral T-Cell lymphoma and transformed mycosis fungoides: SWOG 1108. J. Clin. Oncol 2015;33(21): 2399–2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carson KR, Horwitz SM, Pinter-Brown LC, et al. A prospective cohort study of patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma in the United States. Cancer 2017;123(7):1174–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsi ED, Gruver AM, Foss F. Biomarker quality assurance (QA) findings from the comprehensive oncology measures for peripheral T-Cell lymphoma treatment (COMPLETE) Registry. Blood 2012;120(21): Abstract):4263.23018639 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol 2007;25(5):579–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), Version 5.0 https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcae_v5_quick_reference_5x7.pdf. Published November 27, 2017.

- 27.Goldberg JD, Chou JF, Horwitz S, et al. Long-term survival in patients with peripheral T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Leuk. Lymphoma 2012;53(6): 1124–1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobsen ED, Kim HT, Ho VT, et al. A large single-center experience with allogeneic stem-cell transplantation for peripheral T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma and advanced mycosis fungoides/Sezary syndrome. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol 2011;22(7): 1608–1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.