Abstract

Network analysis is a systems biology-oriented approach based on graph theory that has been recently adopted in various fields of life sciences. Starting from mitochondrial proteomes purified from roots of Cucumis sativus plants grown under single or combined iron (Fe) and molybdenum (Mo) starvation, we reconstructed and analyzed at the topological level the protein–protein interaction (PPI) and co-expression networks. Besides formate dehydrogenase (FDH), already known to be involved in Fe and Mo nutrition, other potential mitochondrial hubs of Fe and Mo homeostasis could be identified, such as the voltage-dependent anion channel VDAC4, the beta-cyanoalanine synthase/cysteine synthase CYSC1, the aldehyde dehydrogenase ALDH2B7, and the fumaryl acetoacetate hydrolase. Network topological analysis, applied to plant proteomes profiled in different single or combined nutritional conditions, can therefore assist in identifying novel players involved in multiple homeostatic interactions.

Keywords: Arabidopsis thaliana, co-expression, Cucumis sativus, iron, molybdenum, network topology, protein–protein interaction, plant nutrition

Introduction

Living organisms are increasingly viewed as integrated and communicating molecular networks, thanks also to the diffusion of data-derived Systems Biology approaches (Barabási and Oltvai, 2004). Such approaches are well established in biomedical and pharmaceutical research (Zhou et al., 2014; Guney et al., 2016) but not widely used in plant science. However, a growing number of plant biologists are adopting them, also to achieve a refined comprehension of plant nutrition (Mai and Bauer, 2016; Di Silvestre et al., 2018; Tsai and Schmidt, 2020).

Plant systems biology studies are dominated by transcriptomic data and statistics that, by measuring the dependence between variables (transcripts), allow us to reconstruct and analyze co-expression network models (Rao and Dixon, 2019). Instead, fewer studies rely on protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks, mainly due to the lack of accurate plant models (Di Silvestre et al., 2018). Nevertheless, the number of studies focusing on high-throughput profiling of plant proteomes (Vigani et al., 2017; Castano-Duque et al., 2018; Santos et al., 2019), on experimental identification of PPIs (Senkler et al., 2017; Osman et al., 2018; Huo et al., 2020) or their computational prediction (Ding and Kihara, 2019) are recently increasing. The computational prediction of PPI is usually inferred by transferring interactions from model plant orthologs, like Arabidopsis thaliana. This approach represents one of the most important resources for network inference in plant organisms, with some flaws, including the identification of false positives and inadequate coverage from associalogs (Lee et al., 2015).

The co-expression networks reconstructed from proteomic data may represent an alternative to the lack of accurate PPI models and a tool for handling, at the system level, large-scale proteomic datasets related to the non-model plant. Similar to transcript networks, protein co-expression networks are defined as an undirected graph where nodes correspond to proteins and edges indicate significant correlation scores. By exploiting the laws underlying graph theory, the identification of hubs/bottlenecks and of differentially correlated proteins are sought, as well as the topological and functional modules related to specific biological phenotypes (Vella et al., 2017).

The studies that elucidate plant iron (Fe) nutrition are steadily increasing due to their impact on alleviating nutritional deficiencies in humans (Murgia et al., 2012, 2013).

Given these premises, we performed the topological analysis of PPI and protein co-expression networks to identify new proteins involved in Fe and molybdenum (Mo) homeostasis in plants by taking into account subcellular compartmentalization. In particular, we reconstructed and analyzed networks from mitochondrial proteomes purified from roots of Cucumis sativus plants grown under single or combined Fe and Mo starvation (Vigani et al., 2017).

Materials and Methods

Reconstruction of C. sativus Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) Networks

A C. sativus PPI network was reconstructed based on homology with A. thaliana by using the STRING v11 database (Szklarczyk et al., 2019). Retrieved homologous interactions were filtered by retaining exclusively those databases annotated and/or experimentally determined with a STRING Score of >0.15 and >0.35, respectively. Following these parameters, a fully connected network of 903 nodes and 10456 edges was built. Four different sub-networks were then extracted by considering the proteins identified in each condition analyzed: +Mo+Fe, 463 nodes and 4118 edges; −Mo+Fe, 466 nodes and 4064 edges; +Mo−Fe, 480 nodes and 4682 edges; and −Mo−Fe, 474 nodes and 4425 edges.

Functional Modules in C. sativus PPI Network

A set of proteins differentially expressed in C. sativus root mitochondria under different conditions (+Mo+Fe, +Mo−Fe, −Mo+Fe, and −Mo−Fe) were selected by Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA, P < 0.05 and F ratio > 3), as previously reported (Vigani et al., 2017). Starting from this set of differentially expressed proteins, a C. sativus PPI network was reconstructed by homology with A. thaliana using STRING v11 database, as reported above. Proteins were grouped in functional modules by the support of BINGO (Maere et al., 2005) and STRING (Doncheva et al., 2019). Cytoscape’s Apps; the network was visualized by the Cytoscape platform, and node color code indicates upregulated (red) and downregulated (light blue) proteins based on Spectral count (SpC) normalization (SpC normalized in the range 0–100, by setting to 100 the higher SpC value per protein).

Reconstruction of C. sativus Protein Co-expression Networks

Protein co-expression networks were reconstructed by processing C. sativus root mitochondria protein profiles characterized under different conditions: +Fe, n = 12; +Mo, n = 14, −Fe, n = 15; −Mo, n = 13. Only proteins identified at least in 51% of the considered samples were retained and processed for each condition. Protein data matrices were processed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient; Spearman’s rank correlation score >|0.7| and P < 0.01 were set as thresholds. All processing was performed using the statistical software JMP15.2, while networks were visualized and analyzed by the Cytoscape platform and its plugins (Su et al., 2014).

Topological Analysis of C. sativus PPI and Protein Co-expression Networks

Both PPI and co-expression networks were topologically analyzed by Centiscape Cytoscape’s App (Scardoni et al., 2014). As for PPI networks, Betweenness and Centroid centralities were calculated, and nodes with values above the average calculated on the whole network were considered hubs (Di Silvestre et al., 2018). On the contrary, a set of differentially correlated proteins were selected in the co-expression network by filtering their Degree centrality.

Results and Discussion

PPI Networks

The analysis of root mitochondria of C. sativus plants grown under Mo and/or Fe starvation led to the identification of 1419 proteins (Vigani et al., 2017). Starting from this proteome, a C. sativus PPI network, connecting 903 nodes through 10464 edges, was built by exploiting the interactions between orthologs in A. thaliana; the average homology between C. sativus and A. thaliana was around 67% (Supplementary Figure 1). A sub-network made of 118 nodes and 388 interactions was extracted by considering proteins (n = 134) whose level was significantly altered in at least one of the four nutritional conditions (control, single or combined Mo and Fe starvation) (Vigani et al., 2017). Proteins belonging to this sub-network were grouped in 21 functional modules, including redox homeostasis, amino acid metabolism, aldehyde dehydrogenases, protein folding, and electron transport chain (Supplementary Figure 2). The analysis of the behavior of their members under the various nutritional conditions indicated above can support the identification of novel candidate genes; in this paragraph, we will highlight some interesting examples.

Fe starvation, combined with Mo starvation or sufficiency, upregulates several proteins involved in amino acid metabolism, such as glutamate dehydrogenases GDH1 and GDH2, aminobutyric acid transaminase POP2 involved in the metabolism of γ-amino butyrate (GABA), which links C and N metabolism in mitochondria (Shelp et al., 2012), aspartate aminotransferase ASP1, the two subunits MCCA and MCCB of methyl crotonyl-CoA carboxylase involved in leucine catabolism, and beta-cyanoalanine synthase/cysteine synthase CYSC1, which detoxifies the cyanide produced as by-product of ethylene synthesis (Hatzfeld et al., 2000; Yamaguchi et al., 2000; Garcia et al., 2010; Arenas-Alfonseca et al., 2018; Supplementary Figure 2). Notably, ethylene is a well-established regulator of Fe deficiency responses (Romera et al., 1999; Lucena et al., 2015). An increased concentration of amino acids has been documented in the xylem sap of Fe deficient cucumber plants (Borlotti et al., 2012). These results suggest that, under Fe starvation, a larger part of the amino acid metabolism takes place in the radical apparatus, with respect to the aerial parts of the plants.

The redox homeostasis group includes formate dehydrogenase (FDH), the enzyme catalyzing the oxidation of formate into CO2 (Alekseeva et al., 2011) and involved in Fe and Mo homeostasis (Vigani et al., 2017; Murgia et al., 2020). This group also includes various proteins upregulated under Fe starvation, such as glutathione peroxidase GPX6, alternative oxidase AOX2, glyoxalase II3/sulfur dioxygenase GLY3, At5g42150 coding for another glutathione peroxidase and aldehyde dehydrogenase ALDH2B7 (Supplementary Figure 2). The aldehyde dehydrogenase enzymes can act as “aldehyde scavengers” of reactive aldehydes produced during the oxidative degradation of membrane lipids (Brocker et al., 2013). In particular, ALDH2B7 converts acetaldehyde into acetic acid (Rasheed et al., 2018). The redox homeostasis group also includes SAG21, which is strongly upregulated under single Mo starvation (Supplementary Figure 2). Perturbation of SAG21 expression affects biomass, flowering, the onset of leaf senescence, the pathogens’ ability to proliferate (Salleh et al., 2012) and alters the function or stability of mitochondrial proteins involved in ROS production and/or signaling (Salleh et al., 2012).

The fatty acid metabolism group includes dihydrolipoamide branched chain acyltransferase BCE2, also known as Dark Inducible 3 (DIN3), whose expression increases soon after exposure to darkness (Fujiki et al., 2000, 2005). The perturbing effects of prolonged darkness on cellular Fe status and its impact on the expression of Fe homeostasis genes are well known: as an example, the light/dark circadian cycles as well as prolonged darkness influence the expression of the iron-storage ferritin, whose gene expression is activated by prolonged darkness (Tarantino et al., 2003) and is circadian-regulated (Duc et al., 2009; Hong et al., 2013). BCE2 is upregulated under Fe starvation (Supplementary Figure 2); this finding is intriguing since darkness is associated with a rise in free Fe ions due to the dismantling of the photosynthetic structures. It would be interesting to investigate BCE2 regulation under Fe excess to establish if BCE2 is upregulated by Fe starvation only or, more generally, by Fe fluctuations.

The protein folding group includes the brassinosteroid (BR) biosynthesis gene DWF1, which mediates BR biosynthesis during the positive growth responses of the root system to low nitrogen (Jia et al., 2020). DWF1 is downregulated under Fe starvation and upregulated under single Mo starvation (Supplementary Figure 2).

The cell cycle/division group includes the mitochondrial GTPase MIRO1 (Supplementary Figure 2), which regulates mitochondrial trafficking and shape in eukaryotic cells. In particular, MIRO1 GTPase influences mitochondrial morphology in A. thaliana pollen tubes (Yamaoka and Leaver, 2008; Sørmo et al., 2011); interacting partners of MIRO GTPases are sought to better elucidate their functions in mitochondrial dynamics (Yamaoka and Hara-Nishimura, 2014). Notably, MIRO1 is upregulated under single Fe or Mo starvation but not under combined deficiencies (Supplementary Figure 2).

The histone/chromatin group includes GYRB2, a DNA topoisomerase (Wall et al., 2004) upregulated under Fe starvation (Supplementary Figure 2).

The translation group includes the pentatricopeptide protein PPR336, which associates with mitochondrial ribosomes (Waltz et al., 2019); PPR336 is downregulated under single Mo starvation, whereas it is upregulated under double Fe and Mo starvation (Supplementary Figure 2).

The electron transport chain group includes the mitochondrial carrier UCP1/PUMP1 transporting aspartateout/glutamatein (as well as other amino acids, dicarboxylates, phosphate, sulfate, and thiosulfate) across the mitochondrial membrane (Monne et al., 2018); such carrier is upregulated in the single or combined Fe or Mo starvation (Supplementary Figure 2).

Transmembrane transporter activity group includes OM47 related to the voltage-dependent anion channel VDAC family; members of this family are major components of the outer mitochondrial membrane and are involved in the channeling of the products of chloroplast breakdown into the mitochondrion and in the exchange of various compounds between the cytosol and the mitochondrial intermembrane space (Li et al., 2016). OM47 is upregulated under single Fe starvation (Supplementary Figure 2). The role of VDAC protein family also emerged by the topological analysis of PPI network. Indeed, 91 PPI hubs were selected in these conditions: 27 hubs in control (+Mo+Fe), 17 hubs in +Mo−Fe, 26 hubs in −Mo+Fe, and 21 hubs in −Mo−Fe (Supplementary Table 1), while 28 PPI hubs were specifically related to sufficiency or starvation of either Fe or Mo (5 hubs in +Fe, 10 hubs in −Fe, 2 hubs in +Mo, and 11 hubs in −Mo) (Supplementary Table 2). In this scenario, VDAC4 and VDAC2 turned out as hubs in PPI networks under Mo starvation (Supplementary Table 2).

The proteins downregulated under Fe or Mo starvation can represent interesting homeostatic regulators in the PPI networks, and their occurrence should not be neglected in future, more extensive analyses; as an example, rice OsIRO3 plays an important role in the Fe deficiency response by negatively regulating the OsNAS3 expression and, thus, nicotianamine NA levels (Wang et al., 2020).

Co-expression Networks

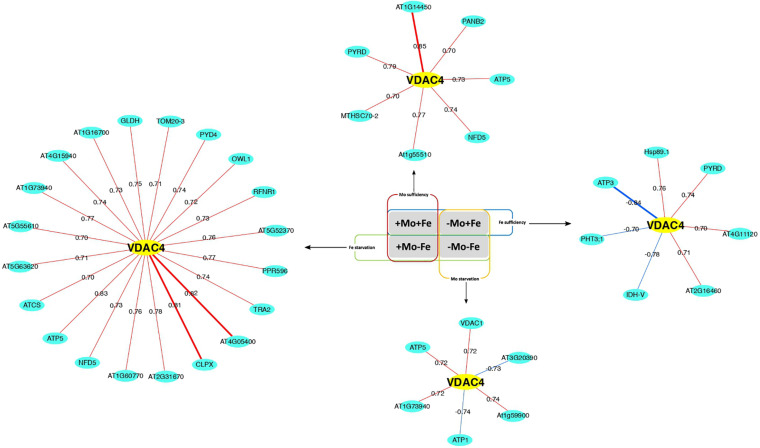

Co-expression networks were reconstructed from proteomes of purified mitochondria of C. sativus plants grown under different Mo and Fe nutritional conditions, reported in Vigani et al. (2017). In particular, the networks were reconstructed under Mo sufficiency (+Mo+Fe and +Mo−Fe conditions, 252 nodes and 1634 edges), Fe sufficiency (+Mo+Fe and −Mo+Fe conditions, 248 nodes and 2193 edges), Fe starvation (+Mo−Fe and −Mo−Fe conditions, 246 nodes and 1911 edges), and Mo starvation (−Mo+Fe and −Mo−Fe conditions, 240 nodes and 1547 edges). Around 5 to 7% of the proteins that were retrieved as co-expressed were also physically interacting (Supplementary Table 3). Following the network topological analysis, proteins belonging to the bioenergetics and amino acids metabolisms were found topologically relevant under Fe sufficiency (18 protein hubs) (Table 1A) or Mo sufficiency (12 protein hubs) (Table 1B). Moreover, 15 proteins emerged as network hubs under Fe starvation (Table 1C) and 16 proteins as hubs under Mo starvation (Table 1D); as examples, we then reconstructed the interactions for three hubs under Mo starvation, i.e. FDH (Table 1D and Supplementary Figure 3), ALDH2B7 (Table 1D and Supplementary Figure 4), CYSC1 (Table 1D and Supplementary Figure 5), and two hubs under Fe starvation, the Voltage-Dependent Ion Channel VDAC4 (Table 1C and Figure 1) and fumaryl acetoacetate hydrolase At4g15940 (Table 1C and Supplementary Figure 6).

TABLE 1.

Proteins differentially correlated in Cucumis sativus co-expression networks (Fe sufficiency, Mo sufficiency, Fe starvation, and Mo starvation).

| Annotation |

LDA |

Degree |

Function | |||||||||

| UNIPROT ID (C. sativus) | Gene name C. sativus | Gene name A. thaliana | Homology | Score | F Ratio | Prob > F | +Fe | +Mo | −Fe | −Mo | ||

| (A) | A0A0A0K4Q8 | Csa_7G073600 | MCCB (AT4G34030) | 77% | 918 | 11,1 | 1,1E-04 | 55 | 5 | 2 | 9 | Methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase, subunit beta |

| A0A0A0LM23 | Csa_2G382440 | FLOT1 (AT5G25250) | 75% | 723 | 4,6 | 1,2E-02 | 51 | Flotilins-like | ||||

| A0A0A0LXD4 | Csa_1G424875 | AT4G30010 | 69% | 142 | 42 | 1 | 2 | 8 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase | |||

| A0A0A0L0B9 | Csa_4G082380 | MBL1 (AT1G78850) | 50% | 434 | 3,9 | 2,1E-02 | 39 | Mannose-binding lectin | ||||

| A0A0A0K5L0 | Csa_7G387180 | MCCA (AT1G03090) | 69% | 1023 | 38 | 4 | 3 | 10 | Methyl crotonyl-CoA carboxylase subunit alpha | |||

| A0A0A0KJ29 | Csa_6G526470 | AT3G58140 | 74% | 657 | 36 | Phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase | ||||||

| A0A0A0KCX8 | Csa_6G077980 | ARGAH1 (AT4G08900) | 85% | 590 | 34 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Arginase | |||

| A0A0A0LBW6 | Csa_3G199630 | EDA9 (AT4G34200) | 83% | 981 | 4 | 1,9E-02 | 33 | 7 | D-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase | |||

| A0A0A0L0I0 | Csa_4G285780 | PA2 (AT5G06720) | 53% | 335 | 3,7 | 2,6E-02 | 33 | 3 | 1 | 3 | Peroxidase | |

| A0A0A0KA81 | Csa_6G088110 | AT2G20420 | 88% | 757 | 31 | 4 | 8 | 12 | Succinyl-CoA ligase | |||

| A0A0A0LBB3 | Csa_3G760530 | SVL1 (AT5G55480) | 56% | 851 | 6,6 | 2,3E-03 | 27 | Glycerophosphoryl diester- phosphodiesterase | ||||

| A0A0A0LFK3 | Csa_3G734240 | TIM9 (AT3G46560) | 82% | 162 | 26 | 0 | 2 | 1 | Translocase of the inner membrane 9 | |||

| A0A0A0KRD9 | Csa_5G613510 | UOX (AT2G26230) | 68% | 434 | 25 | Urate oxidase | ||||||

| A0A0A0L542_ A0A0A0LXV7 | Csa_3G078260 Csa_1G660150 | GPT2 (AT1G61800) | 75% | 568 | 5 | 8,4E-03 | 25 | Glucose-6-phosphate/phosphate translocator | ||||

| A0A0A0K1S9_ A0A0A0K3R7 | Csa_7G047450 Csa_7G047440 | AT2G20710 | 45% | 415 | 24 | 8 | 3 | 1 | PPR-type organelle RNA editing factor | |||

| A0A0A0LS81 | Csa_1G096620 | ASP1 (AT2G30970) | 88% | 768 | 22 | 1 | 11 | 0 | Aspartate transaminase | |||

| A0A0A0LQ27 | Csa_1G025890 | OAT (AT5G46180) | 79% | 738 | 21 | 7 | 3 | Ornithine delta aminotransferase | ||||

| A0A0A0L404 | Csa_4G646110 | FTSH4 (AT2G26140) | 81% | 1128 | 19 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ATP-dependent zinc metalloprotease | |||

| (B) | ||||||||||||

| A0A0A0KIM0 | Csa_6G497010 | NFS1 (AT5G65720) | 78% | 756 | 33 | 2 | Cysteine desulfurase | |||||

| A0A0A0KB82 | Csa_7G407690 | AT5G61310 | 67% | 95,1 | 4 | 27 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit | |||||

| A0A0A0L3T5 | Csa_4G642530 | VDAC2 (AT5G67500) | 53% | 317 | 26 | Voltage-gated anion channel | ||||||

| A0A0A0KMP0 | Csa_5G321480 | AT2G07698 | 93% | 562 | 12 | 22 | 15 | 1 | ATP synthase subunit alpha | |||

| A0A0A0LGF5 | Csa_2G033990 | LON1 (AT5G26860) | 75% | 1456 | 10 | 22 | 9 | 3 | ATP-dependent serine protease | |||

| A0A0A0KW78 | Csa_4G017120 | TOM40-1 (AT3G20000) | 71% | 472 | 9 | 22 | 10 | 4 | Component of mitochondrial outer membrane translocase | |||

| A0A0A0LXK1 | Csa_1G629760 | SDH6 (AT1G08480) | 68% | 144 | 8 | 22 | 13 | 3 | Component of succinate dehydrogenase complex | |||

| A0A0A0KGU5 | Csa_6G500700 | MIC60 (AT4G39690) | 36% | 176 | 17 | 19 | 11 | 8 | Component of mitochondrial transmembrane lipoprotein complex | |||

| A0A0A0KGW6 | Csa_6G366300 | COS1 (AT2G44050) | 66% | 263 | 18,2 | 2,8E-06 | 16 | 5 | 6,7-Dimethyl-8-ribityllumazine synthase | |||

| A0A0A0KMM1 | Csa_5G047770 | AT1G14930 | 36% | 110 | 17 | 15 | Bet v1-type pathogenesis-related protein | |||||

| A0A0A0K9E8 | Csa_6G046410 | SD3 (AT4G00026) | 60% | 297 | 3 | 15 | 2 | 0 | Mitochondrial translocase | |||

| A0A0A0LSR2 | Csa_1G024260 | AT3G18240 | 62% | 506 | 14 | 13 | 9 | Mitochondrial ribosomal subunit | ||||

| (C) | ||||||||||||

| A0A0A0KKV4 | Csa_6G525450 | RFNR1 (AT4G05390) | 78% | 630 | 8 | 2 | 52 | Ferredoxin-NADP + reductase | ||||

| A0A0A0LDA3 | Csa_3G435020 | MPPa1 (AT1G51980) | 63% | 616 | 7,4 | 1,2E-03 | 13 | 6 | 49 | 12 | Subunit alpha of mitochondrial processing peptidase complex | |

| A0A0A0L7Y6 | Csa_3G164480 | AT4G15940 | 76% | 347 | 48 | Fumaryl acetoacetate hydrolase | ||||||

| A0A0A0KH76 | Csa_6G188090 | AT5G52370 | 57% | 151 | 44 | Mitochondrial 28S ribosomal protein S34 | ||||||

| E1B2J6 | GAPDH | GAPC1 | 88% | 610 | 9 | 35 | Glyceraldehyde 3 phosphate dehydrogenase | |||||

| A0A0A0KBL8 | Csa_6G077460 | TKL2 (AT2G45290) | 83% | 1306 | 6,8 | 1,9E-03 | 0 | 5 | 32 | 5 | Transketolase | |

| A0A0A0KRJ5 | Csa_5G168830 | MKP11 (AT5G17165) | 51% | 89 | 9,7 | 2,4E-04 | 29 | Late embryogenesis abundant protein | ||||

| A0A0A0M1R9_ A0A0A0LKR1 | Csa_1G574970 Csa_2G000830 | HXK1 (AT4G29130) | 74% | 757 | 11 | 4 | 27 | 3 | Hexokinase | |||

| A0A0A0KXY5 | Csa_4G337910 | AT5G63620 | 84% | 288 | 4 | 3 | 27 | 2 | Zinc-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase | |||

| A0A0A0LKD3 | Csa_2G346040 | UGP1 (AT5G17310) | 51% | 367 | 13 | 2 | 27 | 11 | UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase | |||

| A0A0A0L2N5 | Csa_4G310720 | FAC1 (AT2G38280) | 80% | 1368 | 5,4 | 6,0E-03 | 22 | 11 | AMP deaminase | |||

| A0A0A0LZS4 | Csa_1G423090 | VDAC4 (AT5G57490) | 63% | 367 | 7 | 7 | 20 | 6 | Voltage-gated anion channel | |||

| A0A0A0LYA6 | Csa_1G532350 | AT4G33070 | 81% | 1042 | 3 | 6 | 19 | 5 | Thiamine pyrophosphate dependent pyruvate decarboxylase | |||

| A0A0A0LQ20 | Csa_2G403690 | CoxX3 (AT1G72020) | 66% | 138 | 16 | 12 | 17 | 9 | TonB-dependent heme receptor A | |||

| A0A0A0KGH2 | Csa_6G502730 | AT2G18330 | 75% | 891 | 17 | 2 | ATPase | |||||

| (D) | ||||||||||||

| A0A0A0LLE7_ A0A0A0KLP6 | Csa_2G372170 Csa_6G497310 | SHM1 (AT4G37930) | 80% | 869 | 9 | 2 | 10 | 28 | Serine hydroxymethyl transferase | |||

| A0A0A0KGA1 | Csa_6G135470 | ALDH5F1 (AT1G79440) | 77% | 813 | 3,5 | 3,0E-02 | 7 | 3 | 9 | 20 | Succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | |

| A0A0A0L5J6 | Csa_3G115030 | AT5G40810 | 87% | 514 | 3,4 | 3,6E-02 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 18 | Cytochrome c1 component of cyt-bc1 complex | |

| A0A0A0LP60 | Csa_2G360050 | SDH5 (AT1G47420) | 56% | 266 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 16 | Succinate dehydrogenase subunit 5 | |||

| A0A0A0KP30 | Csa_5G199270 | PIP1;4 (AT4G00430) | 87% | 523 | 15,4 | 1,0E-05 | 10 | 11 | 3 | 19 | Aquaporin | |

| A0A0A0LJB4 | Csa_2G010420 | ALDH2B7 (AT1G23800) | 80% | 888 | 18,3 | 2,7E-06 | 0 | 7 | 3 | 21 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase | |

| A0A0A0KYN6 | Csa_4G192110 | GDH1 (AT5G18170) | 91% | 788 | 24,1 | 2,7E-07 | 9 | 11 | 2 | 20 | Glutamate dehydrogenase | |

| A0A0A0KWX8 | Csa_4G050830 | PGD1 (AT1G64190) | 87% | 892 | 15,9 | 8,2E-06 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 24 | Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase | |

| A0A0A0KX20 | Csa_4G052590 | NDPK4 (AT4G23900) | 78% | 387 | 4,8 | 9,4E-03 | 15 | 2 | 1 | 14 | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase | |

| A0A0A0LHY6 | Csa_3G836500 | FDH (AT5G14780) | 83% | 628 | 15,4 | 1,0E-05 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 22 | Formate dehydrogenase | |

| A0A0A0K9Z6 | Csa_6G004600 | CYSC1 (AT3G61440) | 79% | 588 | 28,4 | 6,5E-08 | 8 | 11 | 0 | 16 | b-cyanoalanine synthase/cysteine synthase | |

| A0A0A0KKD9 | Csa_5G149330 | BIP2 (AT5G42020) | 91% | 1229 | 3,3 | 3,7E-02 | 14 | 20 | Heat shock protein 70 | |||

| A0A0A0K7B3 | Csa_7G222870 | CYS4 (AT4G16500) | 35% | 96 | 10,2 | 1,9E-04 | 5 | 22 | Cysteine-type endopeptidase inhibitor | |||

| A0A0A0LYF4 | Csa_1G710160 | 33 | Cysteine-type endopeptidase inhibitor | |||||||||

| (D) | A0A0A0KVK8 A0A0A0LRR3_ A0A0A0LDZ4 | Csa_4G094520 Csa_2G369070 Csa_3G889810 | GF14 (AT1G35160) | 93% | 482 | 33 | 14-3-3 protein | |||||

| A0A0A0K6A8 | Csa_7G070770 | TUA4 (AT1G04820) | 98% | 869 | 3,5 | 3,3E-02 | 17 | Tubulin | ||||

Protein selection was based on the differential node Degree: Proteins with a Degree above the Network Average Degree (in bold) were retained. For each selected C. sativus protein, the C. sativus gene name, the name of A. thaliana homologous gene and the corresponding homology (in percent value and score), Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) parameters (only for differentially expressed proteins), and node Degree in the various nutritional conditions are reported. Homologies were retrieved by STRING database. Co-expression hubs in (A) Fe sufficiency (+Mo+Fe, −Mo+Fe), (B) Mo sufficiency (+Mo+Fe, +Mo−Fe), (C) Fe starvation (+Mo−Fe, −Mo−Fe) and (D) Mo starvation (−Mo+Fe, −Mo−Fe) are shown. Each accession number within brackets refers to the A. thaliana gene reported on the upper line.

FIGURE 1.

Differential VDAC4 correlation degree in co-expression networks. Cucumis sativus root mitochondria proteins identified under different conditions (+Mo+Fe, +Mo–Fe, –Mo+Fe, and –Mo–Fe) were analyzed according to their grouping into Fe sufficiency, Mo sufficiency, Fe starvation, and Mo starvation. Red and blue edges indicated positive and negative correlations, respectively. Edges width is proportional to Spearman’s correlation score (P < 0.01).

Formate dehydrogenase has been associated with stress responses in plants (Hourton-Cabassa et al., 1998; Shiraishi et al., 2000; Herman et al., 2002; Lou et al., 2016; Murgia et al., 2020), and it takes part in Fe and Mo homeostasis (Vigani et al., 2017; Murgia et al., 2020).

While FDH is co-expressed with a low number of proteins under Fe sufficiency, Fe starvation, and Mo sufficiency, such number strikingly increases under Mo starvation. Indeed, under this condition, FDH is co-expressed with 22 proteins (Table 1); some of these 22 proteins belong to amino acid/protein metabolisms (e.g., NADH dehydrogenase ubiquinone 1 encoded by AT3G08610; aspartic-type endopeptidase APF1; mitochondrial peptidase (MPPBETA) or redox activity (ALDH5F1, ALDH2B7, ALDH6B2; POP2; BCE2) (Supplementary Figure 3).

ALDH2B7 and CYSC1 are themselves hubs under Mo starvation (Table 1); indeed, under this condition, 21 different proteins are co-expressed with ALDH2B7, whereas, under the other conditions, a total of 10 proteins are co-expressed with ALDH2B7 (Table 1). The majority of these are involved in the synthesis/utilization of acetyl CoA metabolic intermediate, such as (i) MCCB (3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase) involved in the branched chain amino acids metabolism and (ii) ATCS (citrate synthase) and SDH1-1 (succinate dehydrogenase) involved in TCA cycle (Supplementary Figure 4). The modulation of ALDH2B7 expression observed under stress might play a role in the aerobic detoxification of acetaldehyde in plants (Rasheed et al., 2018). The presence of several co-expressed proteins involved in amino acids and GABA metabolisms (GDH1, POP2), in formate metabolism (FDH), and in the nucleotide metabolism (FAC1, adenosine 5 monophosphate deaminase) suggests that such acetaldehyde detoxification might be targeted to the synthesis of precursor for the synthesis of nucleotides. Plants possess metabolic pathways for the de novo synthesis of purine nucleotides producing AMP as well as pyrimidine nucleotides producing UMP (Witte and Herde, 2020.) Nucleotides are synthesized from amino acids like Glutamine, Aspartic acid, Glycine, and formyl tetrahydrofolate; the latter is a metabolite related to FDH and formate metabolism (Witte and Herde, 2020).

CYSC1 is co-expressed, under Mo starvation, with 16 proteins whereas it is co-expressed with 11 proteins, under Mo sufficiency (Table 1); interestingly, two glutamate dehydrogenase isoforms, GDH1 and GDH2, are co-expressed with CYSC1, under Mo starvation and Mo sufficiency, respectively, but not under Fe sufficiency or Fe starvation (Supplementary Figure 5). GDHs are enzymes at the branch point between carbon and nitrogen metabolism; both isoforms are localized in mitochondria and GDH2 unless GDH1 is calcium-stimulated (Grzechowiak et al., 2020).

AC4 interacts with tRNAs, and it might be involved in their transport into mitochondria (Hemono et al., 2020); accordingly, atvdac4 mutant shows severely compromised growth (Hemono et al., 2020). Under Fe starvation, VDAC4 is a hub of two pentatricopeptide-repeat-containing proteins, i.e., PPR596 and At1g60770 (Figure 1). PPR proteins are nuclear-encoded RNA-binding proteins containing repeated motives of approximately 35 aa (Doniwa et al., 2010). PPR596 is involved in the partial C-to-U RNA editing events in the mitochondrial genome and, possibly, also in transcript stabilization and stimulation of translation (Doniwa et al., 2010). Both PPR596 and another PPR protein encoded by At1g60770 also belonging to the VDAC4 co-expression network under Fe starvation (Figure 1) are the closest homologs of the mitochondrial PPR protein PACO1, which affects the flowering time in A. thaliana (Emami and Kempken, 2019). VDAC4 is also the hub, under Fe starvation, of L-galactono 1-4 lactone dehydrogenase GLDH, the enzyme that catalyzes the last step in the biosynthesis of ascorbic acid in plants (Wheeler et al., 2015).

VDAC4 is a co-expressed protein of the fumaryl acetoacetate hydrolase (Supplementary Figure 6) and both of them are also hubs in +Fe−Mo and −Fe−Mo PPI networks (Supplementary Table 2). The fumaryl acetoacetate hydrolase catalyzes the formation of fumarate and acetoacetate in the L-tyrosine (Tyr) degradation pathway in plants (Dixon and Edwards, 2006). Altogether, 48 proteins are co-expressed with the fumaryl acetoacetate hydrolase under Fe starvation but none in the other conditions.

Conclusion

We hereby show how the topological network analysis applied to proteomes obtained from mitochondria purified from plants grown under Fe and/or Mo starvation suggests FDH as a hub of Mo nutrition in agreement with experimental observations (Vigani et al., 2017; Murgia et al., 2020). Such analysis could also suggest other potential hubs for Fe and Mo nutrition, such as VDAC4, CYSC1, ALDH2B7, and fumaryl acetoacetate hydrolase among others, which will be object of our future investigations. VDAC4 and fumaryl acetoacetate hydrolase were found to be hubs by both PPI and protein co-expression networks. The different origin of these network models (basically PPI reconstructed from literature, while co-expression networks from experimental data) strengthens the hypothesis that these two proteins may play a role in Fe and Mo homeostasis, and it confirms the complementarity and synergy of these two approaches in identifying candidate proteins with a role in the processes underlying the investigated phenotypes.

Although the approaches based on computational prediction present some intrinsic limitations, including false-positive interactions or the lack of true ones, they nevertheless promote and support new experimental avenues, including large-scale experimental identification of PPIs, which will improve the effectiveness and accuracy of the proposed approaches.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

DD, PMo, GV, and IM conceived the work. DD reconstructed the PPI and co-expression networks with contributions from PMa and SH. IM, GV, and PMo analyzed all the networks and their biological relevance. IM wrote the manuscript with contributions from DD, GV, and PMo. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This research was supported by funds from the Italian National Ministry of Research (MIUR) PRIN 2017-2017FBS8YN_00 (DD), local research funds of the Department of Life Sciences and Systems Biology, University of Turin (GV), and Fondo per il Finanziamento delle Attività Base di Ricerca 2017 (PMo).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2021.629013/full#supplementary-material

Homology between C. sativus and A. thaliana proteins.

Differentially expressed proteins and A. thaliana PPI network modules.

Differential FDH correlation degree in co-expression networks.

Differential ALDH2B7 correlation degree in co-expression networks.

Differential CYSC1 correlation degree in co-expression networks.

Differential fumaryl acetoacetate hydrolase correlation degree in co-expression networks.

PPI hubs in the four nutritional conditions: control (+Fe+Mo), Mo starvation (+Fe−Mo), Fe starvation (−Fe+Mo), Mo and Fe starvation (−Fe−Mo).

PPI hubs in the four nutritional conditions: Fe sufficiency (consisting in +Mo and −Mo samples), Fe starvation (consisting in +Mo and −Mo samples), Mo sufficiency (consisting in +Fe and −Fe samples), and Mo starvation (consisting in +Fe and −Fe samples).

Co-expression and physical interaction under Fe sufficiency (+Fe+Mo and +Fe−Mo samples), Mo sufficiency (+Fe+Mo and −Fe+Mo), Fe starvation (−Fe+Mo, −Fe−Mo), and Mo starvation (+Fe−Mo, −Fe−Mo).

References

- Alekseeva A. A., Savin S. S., Tishkov V. I. (2011). NAD+-dependent formate dehydrogenase from plants. Acta Nat. 3 38–54. 10.32607/20758251-2011-3-4-38-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenas-Alfonseca L., Gotor C., Romero L. C., Garcia I. (2018). ß-Cyanoalanine Synthase action in root hair elongation is exerted at early steps of the root hair elongation pathway and is independent of direct cyanide inactivation of NADPH oxidase. Plant Cell Physiol. 59 1072–1083. 10.1093/pcp/pcy047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barabási A. L., Oltvai Z. N. (2004). Network biology: understanding the cell’s functional organization. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5 101–113. 10.1038/nrg1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borlotti A., Vigani G., Zocchi G. (2012). Iron deficiency affects nitrogen metabolism in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) plants. BMC Plant Biol. 12:189. 10.1186/1471-2229-12-189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocker C., Vasiliou M., Carpenter S., Carpenter C., Zhang Y., Wang X., et al. (2013). Aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) superfamily in plants: gene nomenclature and comparative genomics. Planta 237 189–210. 10.1007/s00425-012-1749-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castano-Duque L., Helms A., Ali J. G., Luthe D. S. (2018). Plant bio-wars: maize protein networks reveal tissue-specific defence strategies in response to a root herbivore. J. Chem. Ecol. 44 727–745. 10.1007/s10886-018-0972-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Silvestre D., Bergamaschi A., Bellini E., Mauri P. (2018). Large scale proteomic data and network-based systems biology approaches to explore the plant world. Proteomes 6:27. 10.3390/proteomes6020027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z., Kihara D. (2019). Computational identification of protein-protein interactions in model plant proteomes. Sci. Rep. 9:8740. 10.1038/s41598-019-45072-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon D. P., Edwards R. (2006). Enzymes of tyrosine catabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Sci. 171 360–366. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2006.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doncheva N. T., Morris J. H., Gorodkin J., Jensen L. J. (2019). Cytoscape StringApp: network analysis and visualization of proteomics data. J. Proteome Res. 18 623–632. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doniwa Y., Ueda M., Uueta M., Wada A., Kadowaki K., Tsutsumi N. (2010). The involvement of a PPR protein of the P subfamily in partial RNA editing of an Arabidopsis mitochondrial partial transcript. Gene 454 39–46. 10.1016/j.gene.2010.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duc C., Cellier F., Lobréaux S., Briat J. F., Gaymard F. (2009). Regulation of iron homeostasis in Arabidopsis thaliana by the clock regulator time for coffee. J. Biol. Chem. 284 36271–36281. 10.1074/jbc.M109.059873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emami H., Kempken F. (2019). PRECOCIOUS1 (POCO1), a mitochondrial pentatricopeptide repeat protein affects flowering time in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 100 265–278. 10.1111/tpj.14441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiki Y., Nakagawa Y., Furumoto T., Yoshida S., Biswal B., Ito M., et al. (2005). Response to darkness of late-responsive dark-inducible genes is positively regulated by leaf age and negatively regulated by calmodulin-antagonist-sensitive signalling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 46 1741–1746. 10.1093/pcp/pci174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiki Y., Sato T., Ito M., Watanabe A. (2000). Isolation and characterization of cDNA clones for the E1β and E2 subunits of branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase complex in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 275 6007–6013. 10.1074/jbc.275.8.6007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia I., Castellano J. M., Vioque B., Solano R., Gotor C., Romero L. C. (2010). Mitochondrial β-Cyanoalanine Synthase is essential for root hair formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 22 3268–3279. 10.1105/tpc.110.076828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzechowiak M., Sliwiak J., Jaskolski M., Ruszkowski M. (2020). Structural studies of glutamate dehydrogenase (Isoform 1) from Arabidopsis thaliana, an important enzyme at the branch-point between carbon and nitrogen metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 11:754. 10.3389/fpls.2020.00754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guney E., Menche J., Vidal M., Barabasi A. L. (2016). Network-based in silico drug efficacy screening. Nat. Commun. 7:10331. 10.1038/ncomms10331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzfeld Y., Maruyama A., Schmidt A., Noji M., Ishizawa K., Saito K. (2000). β-Cyanoalanine Synthase is a mitochondrial Cys synthase-like protein in spinach and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 123 1163–1172. 10.1104/pp.123.3.1163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemono M., Ubrig E., Salinas-Giegé T., Drouard L., Duchêne A. M. (2020). Arabidopsis voltage-dependent anion channels (VDACs): overlapping and specific functions in mitochondria. Cells 9:1023. 10.3390/cells9041023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman P. L., Ramberg H., Baack R. D., Markwell J., Osterman J. C. (2002). Formate dehydrogenase in Arabidopsis thaliana: overexpression and subcellular localization in leaves. Plant Sci. 163 1137–1145. 10.1016/s0168-9452(02)00326-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S., Kim S. A., Guerinot M. L., McClung C. R. (2013). Reciprocal interaction of the circadian clock with the iron homeostasis network in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 161 893–903. 10.1104/pp.112.208603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hourton-Cabassa C., Ambard-Bretteville F., Moreau F., Davy de Virville J., Remy R., Colas des Francs-Small C. (1998). Stress induction of mitochondrial formate dehydrogenase in potato leaves. Plant Physiol. 116 627–635. 10.1104/pp.116.2.627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo R., Liu Z., Yu X., Li Z. (2020). The interaction network and signaling specificity of two-component system in Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 4898. 10.3390/ijms21144898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Z., Giehl R. F. H., von Wirén N. (2020). The root foraging response under low nitrogen depends on DWARF1-mediated brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 183 998–1010. 10.1104/pp.20.00440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Kim H., Lee I. (2015). Network-assisted crop systems genetics: network inference and integrative analysis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 24 61–70. 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Kubiszewski-Jakubiak S., Radomiljac J., Wang Y., Law S. R., Keech O., et al. (2016). Characterization of a novel β-barrel protein (AtOM47) from the mitochondrial outer membrane of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 67 6061–6075. 10.1093/jxb/erw366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou H. Q., Gong Y. L., Fan W., Xu J. M., Liu Y., Cao M. J., et al. (2016). A formate dehydrogenase confers tolerance to aluminum and low pH. Plant Physiol. 171 294–305. 10.1104/pp.16.01105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucena C., Romera F. J., García M. J., Alcántara E., Pérez-Vicente R. (2015). Ethylene participates in the regulation of Fe deficiency responses in Strategy I plants and in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 6:1056. 10.3389/fpls.2015.01056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maere S., Heymans K., Kuiper M. (2005). BiNGO: a cytoscape plugin to assess overrepresentation of Gene Ontology categories in biological networks. Bioinformatics 21 3448–3449. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai H. J., Bauer P. (2016). From the proteomic point of view: integration and adaptive changes to iron deficiency in plants. Curr. Plant Biol. 5 45–56. 10.1016/j.cpb.2016.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monne M., Daddabbo L., Gagneul D., Obata T., Hielscher B., Palmieri L., et al. (2018). Uncoupling proteins 1 and 2 (UCP1 and UCP2) from Arabidopsis thaliana are mitochondrial transporters of aspartate, glutamate, and dicarboxylates. J. Biol. Chem. 293 4213–4227. 10.1074/jbc.RA117.000771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murgia I., Arosio P., Tarantino D., Soave C. (2012). Biofortification for combating “hidden hunger” for iron. Trends Plant Sci. 17 47–55. 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murgia I., De Gara L., Grusak M. (2013). Biofortification: how can we exploit plant science to reduce micronutrient deficiencies? Front. Plant Sci. 4:429. 10.3389/fpls.2013.00429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murgia I., Vigani G., Di Silvestre D., Mauri P., Rossi R., Bergamaschi A., et al. (2020). Formate dehydrogenase takes part in molybdenum and iron homeostasis and affects dark-induced senescence in plants. J. Plant Interact. 15 386–397. [Google Scholar]

- Osman K., Yang J., Roitinger E., Lambing C., Heckmann S., Howell E., et al. (2018). Affinity proteomics reveals extensive phosphorylation of the Brassica chromosome axis protein ASY1 and a network of associated proteins at prophase I of meiosis. Plant J. 93 17–33. 10.1111/tpj.13752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao X., Dixon R. A. (2019). Co-expression networks for plant biology: why and how. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 51 981–988. 10.1093/abbs/gmz080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed S., Bashir K., Kim J. M., Ando M., Tanaka M., Seki M. (2018). The modulation of acetic acid pathway genes in Arabidopsis improves survival under drought stress. Sci. Rep. 8:7831. 10.1038/s41598-018-26103-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romera F., Alcantara E., De la Guardia M. (1999). Ethylene production by Fe-deficient roots and its involvement in the regulation of Fe-deficiency stress responses by strategy I plants. Ann. Bot. 83 51–55. 10.1006/anbo.1998.0793 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salleh F. M., Evans K., Goodall B., Machin H., Mowla S. B., Mur L. A. J., et al. (2012). A novel function for a redox-related LEA protein (SAG21/AtLEA5) in root development and biotic stress responses. Plant Cell Environ. 35 418–429. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02394.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos C., Nogueira F. C. S., Domont G. B., Fontes W., Prado G. S., Habibi P., et al. (2019). Proteomic analysis and functional validation of a Brassica oleracea endochitinase involved in resistance to Xanthomonas campestris. Front. Plant Sci. 10:414. 10.3389/fpls.2019.00414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scardoni G., Tosadori G., Faizan M., Spoto F., Fabbri F., Laudanna C. (2014). Biological network analysis with CentiScaPe: centralities and experimental dataset integration. F1000 Res. 3:139. 10.12688/f1000research.4477.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senkler J., Senkler M., Eubel H., Hildebrandt T., Lengwenus C., Schertl P., et al. (2017). The mitochondrial complexome of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 89 1079–1092. 10.1111/tpj.13448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelp B., Mullen R. T., Waller J. C. (2012). Compartmentation of GABA metabolism raises intriguing questions. Trends Plant Sci. 17 57–59. 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiraishi T., Fukusaki E., Miyake C., Yokota A., Kobayashi A. (2000). Formate protects photosynthetic machinery from photoinhibition. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 89 564–568. 10.1016/s1389-1723(00)80058-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørmo C. G., Brembu T., Winge P., Bones A. M. (2011). Arabidopsis thaliana MIRO1 and MIRO2 GTPases are unequally redundant in pollen tube growth and fusion of polar nuclei during female gametogenesis. PLoS One 6:e18530. 10.1371/journal.pone.0018530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su G., Morris J. H., Demchak B., Bader G. D. (2014). Biological network exploration with Cytoscape 3. Curr. Prot. Bioinformatics 47 8.13.1–8.13.24. 10.1002/0471250953.bi0813s47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk D., Gable A. L., Lyon D., Junge A., Wyder S., Huerta-Cepas J., et al. (2019). STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 47 D607–D613. 10.1093/nar/gky1131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarantino D., Petit J. M., Lobreaux S., Briat J. F., Soave C., Murgia I. (2003). Differential involvement of the IDRS cis-element in the developmental and environmental regulation of the AtFer1 ferritin gene from Arabidopsis. Planta 217 709–716. 10.1007/s00425-003-1038-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai H., Schmidt W. (2020). pH-dependent transcriptional profile changes in iron-deficient Arabidopsis roots. BMC Genomics 21:694. 10.1186/s12864-020-07116-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vella D., Zoppis I., Mauri G., Mauri P., Di Silvestre D. (2017). From protein-protein interactions to protein co-expression networks: a new perspective to evaluate large-scale proteomic data. EURASIP J. Bioinformatics Syst. Biol. 2017:6. 10.1186/s13637-017-0059-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigani G., Di Silvestre D., Agresta A. M., Donnini S., Mauri P., Gehl C., et al. (2017). Molybdenum and iron mutually impact their homeostasis in cucumber (Cucumis sativus) plants. New Phytol. 213 1222–1241. 10.1111/nph.14214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall M. K., Mitchenall L. A., Maxwell A. (2004). Arabidopsis thaliana DNA gyrase is targeted to chloroplasts and mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 7821–7826. 10.1073/pnas.0400836101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltz F., Nguyen T., Arrivé M., Bochler A., Chicher J., Hammann P., et al. (2019). Small is big in Arabidopsis mitochondrial ribosome. Nat. Plants 5 106–117. 10.1038/s41477-018-0339-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Ye J., Ma Y., Wang T., Shou H., Zheng L. (2020). OsIRO3 plays an essential role in iron deficiency responses and regulates iron homeostasis in rice. Plants 9:1095. 10.3390/plants9091095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler G., Ishikawa T., Pornsaksit V., Smirnof N. (2015). Evolution of alternative biosynthetic pathways for vitamin C following plastid acquisition in photosynthetic eukaryotes. eLife 4:e06369. 10.7554/eLife.06369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte C. P., Herde M. (2020). Nucleotide metabolism in plants. Plant Physiol. 182 63–78. 10.1104/pp.19.00955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y., Nakamura T., Kusano T., Sano H. (2000). Three Arabidopsis genes encoding proteins with differential activities for cysteine synthase and beta-cyanoalanine synthase. Plant Cell Physiol. 41 465–476. 10.1093/pcp/41.4.465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka S., Hara-Nishimura I. (2014). The mitochondrial ras-related GTPase Miro: views from inside and outside the metazoan kingdom. Front. Plant Sci. 5:350. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka S., Leaver C. J. (2008). EMB2473/MIRO1, an Arabidopsis Miro GTPase, is required for embryogenesis and influences mitochondrial morphology in pollen. Plant Cell 20 589–601. 10.1105/tpc.107.055756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Menche J., Barabási A. L., Sharma A. (2014). Human symptoms-disease network. Nat. Commun. 5:4212. 10.1038/ncomms5212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Homology between C. sativus and A. thaliana proteins.

Differentially expressed proteins and A. thaliana PPI network modules.

Differential FDH correlation degree in co-expression networks.

Differential ALDH2B7 correlation degree in co-expression networks.

Differential CYSC1 correlation degree in co-expression networks.

Differential fumaryl acetoacetate hydrolase correlation degree in co-expression networks.

PPI hubs in the four nutritional conditions: control (+Fe+Mo), Mo starvation (+Fe−Mo), Fe starvation (−Fe+Mo), Mo and Fe starvation (−Fe−Mo).

PPI hubs in the four nutritional conditions: Fe sufficiency (consisting in +Mo and −Mo samples), Fe starvation (consisting in +Mo and −Mo samples), Mo sufficiency (consisting in +Fe and −Fe samples), and Mo starvation (consisting in +Fe and −Fe samples).

Co-expression and physical interaction under Fe sufficiency (+Fe+Mo and +Fe−Mo samples), Mo sufficiency (+Fe+Mo and −Fe+Mo), Fe starvation (−Fe+Mo, −Fe−Mo), and Mo starvation (+Fe−Mo, −Fe−Mo).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.