Abstract

Drosophila melanogaster has been used as a model organism for study on development and pathophysiology of the heart. LIM domain proteins act as adaptors or scaffolds to promote the assembly of multimeric protein complexes. We found a total of 75 proteins encoded by 36 genes have LIM domain in Drosophila melanogaster by the tools of SMART, FLY-FISH, and FlyExpress, and around 41.7% proteins with LIM domain locate in lymph glands, muscles system, and circulatory system. Furthermore, we summarized functions of different LIM domain proteins in the development and physiology of fly heart and hematopoietic systems. It would be attractive to determine whether it exists a probable “LIM code” for the cycle of different cell fates in cardiac and hematopoietic tissues. Next, we aspired to propose a new research direction that the LIM domain proteins may play an important role in fly cardiac and hematopoietic morphogenesis.

Keywords: Drosophila melanogaster, LIM domain, cardiac, hematopoietic, development

Introduction

The Drosophila melanogaster has emerged as a powerful model for studying heart development and cardiac diseases. Using the tools of both classical and molecular genetics, the study of the phylogeny of fly heart has been influential in the denomination of the primary signaling events of cardiac area formation, cardiomyocyte specification, and the formation of the functioning heart tube (1). Several studies that are underway may take advantage of the fruit fly as an in vivo model for exploring genes involved in cardiac formation. Numerous mutations in conserved hereditary pathways have been found, including those commanding development and physiology of the heart (2). The function and expression pattern of the homeobox transcription factor Tinman in Drosophila and its vertebrate homologous NKX2.5 are remarkably similar in the embryology of heart tube morphogenesis and heart function, and this strikingly provides the compelling evidence that heart development is controlled by conserved homologous pathways in both invertebrates and vertebrates (2–6). After that, many transcription factors, and signal pathways involved in the cardiac specification has been elucidated. Pnr is essential in the mesoderm for initiation of cardiac-specific expression of tinman and for specification of the heart primordium (7). Wnt signaling activated by Wg, together with Dpp, is required for specification of cardiac progenitor cells in early heart development (8). These basic determinants of cardiogenesis in the fly play elementary roles in both the immature cardiac specification and heart function in the adult fly and human (4).

Heart progenitors of flies are bilaterally symmetrical, distributed in most of dorsal regions of the mesoderm in Drosophila (9). During cardiogenesis, these progenitors migrate to the dorsal midline and form the heart tube, a stretchable linear tube, which is consisted of two different types of cells, ie. contractile myocardial cells in the inner layer and non-contractile pericardial cells. Pericardial cells are the excretory cells, called pericardial nephrocytes (10, 11). Drosophila melanogaster also shares with vertebrates the basic regulatory mechanisms and genetic control of hematopoiesis, making it a good model for solving outstanding problems in blood development (12, 13). Lymph organ, the hematopoietic system in Drosophila, which produces the hemolymph cells, is derived from the cardiac progenitors, some genes that affect heart development may also be involved in regulating the differentiation of blood cells (14). Drosophila has three classes of blood cells: plasmatocytes, lamellocytes, and crystal cells. The development of crystal cells, a non-phagocytic cell, is similar to the vertebrate erythroid development in the early phase (15, 16). Despite its simple structure, the fly heart has recently emerged as an admirable model system for dissecting complicated pathways that determine the fate of cardiac cells and studying the physiological functions of the adult heart (17).

LIM is a small protein-protein synergism domain containing two zinc fingers (18). LIM domains are identified in a dissimilar group of proteins with a wide variety of biological roles, including gene expression regulation, cell fate determination, cytoskeleton organization, tumor formation, and embryonic development (19). LIM domains function as adaptors or scaffolds to support the assembly of multimeric protein complexes via interacting with alteration protein partners. LIM domains generally have about 50–60 amino acids and are characterized by two highly conserved zinc finger motifs. These zinc fingers contain eight conserved residues, generally with cysteines and histidines coordinately binding to two zinc atoms. The consensus sequence of LIM domain has been defined as C-X(2)-C-X(16, 23)-H-X(2)-[CH]-X(2)-C-X(2)-C-X(16,21)-C-X(2,3)-[CHD] (where X denotes any amino acid) (18–20).

In this review, Firstly, we found a total of 75 proteins encoded by 36 genes have LIM domain in Drosophila melanogaster by the tools of SMART, and most proteins with LIM domain locate in lymph glands, muscles system, and circulatory system according to FLY-FISH, and FlyExpress. Secondly, we summarized functions of four LIM domain proteins in the development and physiology of fly heart and hematopoietic systems. Lastly, we aspired to propose a new research direction that other LIM domain proteins may play an important role in fly cardiac and hematopoietic morphogenesis. Based on the expression parrerns, and biological roles of the LIM domain, we speculated that it has an important function involved in Drosophila heart development, heart function, and/or hematopoietic morphogenesis. Therefore, this review focus on the roles of LIM domain proteins in Drosophila cardiac and hematopoietic morphogenesis.

Bioinformatics Analysis of Drosophila LIM Domain Proteins

SMART (Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool) is a web resource for the identification and annotation of protein domains and the analysis of protein domain architectures (http://smart.embl.de) (21, 22). We used the SMART tool to identify proteins containing the LIM domain in Drosophila melanogaster. It is expected that a total of 36 genes encoding 75 proteins with the LIM domain in Drosophila melanogaster (Table 1). According to the characteristics of protein domains, LIM-domain proteins were classified into three types, LIM proteins, which include the LIM domain and other protein structures; LIM-only types with only the LIM domain; and LIM-homeodomain (LIM-HD) types, which include the LIM domain and homeodomain domain. These genes participate in the biological functions of various organs and tissues such as muscle, heart, lymph gland, nervous system, eye development, and leg morphogenesis, and so on (Table 1). Then we evaluated the expression regions of these genes in fruit flies by two databases. One is Fly-FISH (http://fly-fish.ccbr.utoronto.ca/), a database documents the expression and localization patterns of Drosophila mRNAs at the cellular and subcellular level during early embryogenesis and third instar larval tissues (Figures 2G–M) (23, 24). The other is FlyExpress (http://www.flyexpress.net/), a freely approachable online knowledgebase offering users an occasion to investigate and analyze expression patterns of developmental genes in Drosophila embryogenesis (Figures 2A–F) (25–27). According to the FLY-FISH or FlyExpress databases, there are 15 LIM genes expressed in mesoderm including muscles, heart, or lymph glands (Figure 1 Columm A). It indicates that 11 LIM genes are expressed in other non-Columm A tissues (Figure 1 Columm B). The expression patterns of the remaining 10 LIM genes are unclear (Figure 1 Columm C). From these two databases, we perceived that some of the 36 genes were expressed in the heart (Table 1 and Figures 2A–J), lymph gland (Table 1 and Figures 2K–M), muscle, CNS, and amnioserosa (Table 1), and so on. In general, around 41.7% Drosophila LIM domain genes were enriched expressed in mesoderm including muscles, heart, or lymph glands (Figure 1 Columm A), and this signified that these genes might have a important role in heart, and/or hematopoietic development. In the accompanying sections, we introduced some specific LIM domain proteins, tailup, mlp84B, radish, and Beadex, which have been confirmed by scientists, play roles in cardiac, and/or hematopoietic morphogenesis. However other LIM domain genes, which enriched expressed in heart, lymph glands, or other tissues, whether it is related to heart development, heart function, or hematopoietic morphogenesis remains to be further studied. In a word, we provide a new idea for the future research.

Table 1.

List of the various transcripts and proteins with LIM domain in Drosophila melanogaster.

| FlyBase ID | gene | UniProt IDs | FLY-FISH | FlyExpress | LIM-type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBgn0263934 | Esn |

A0A0B4KED7 A0A0B4KEK5 |

N/A | N/A | LIM protein |

| FBgn0013751 | Awh | M9PEI5 | Brain, Ectoderm, Optic lobes, primordium, Posterior spiracles, Segmentedpattern, lymph glands | N/A | LIM-homeodomain (LIM-HD) |

| FBgn0259209 | Mlp60A | B7YZP9 | Muscle, Posterior spiracles | Muscle system, Dorsal prothoracic, Pharyngeal muscle, | LIM-Only |

| FBgn0263346 | Smash | A0A0B4K615 | CNS, Dorsal vessel, Ectoderm, Head, Hindgut, muscle, Visceral mesoderm, Segmented pattern | Dorsal apodeme, Dorsal epidermis, Hindgut | LIM protein |

| FBgn0053208 | Mical | Q86BA1, A0A0B4K703, A0A0B4K6D5, A0A0B4K6N6, A0A126GUS6, A0A126GUS4 | Blastoderm nuclei, Yolk nuclei, Zygotic | Midgut, Muscle system, Morsal prothoracic, Pharyngeal muscle | LIM protein |

| FBgn0036333 | Mical-like | Q9VU34 | API | Malpighiantubule, Midgut, Trunk mesoderm | LIM protein |

| FBgn0265991 | Zasp52 | A1ZA47, A0A0B4KER6, A0A0B4KEW3, A0A0B4KFR8, A0A0B4LGL0, C1C3E7 G3JX28, G3JX25 G3JX27, G3JX29 G3JX30, G3JX31, G3JX32 G3JX33 | Amnioserosa, API, CNS, Midgut, Segmented pattern | Amnioserosa | LIM protein |

| FBgn0051352 | Unc-115a | A0A0B4LGY0 E1JIH3 | API, Ectoderm, Neuroblasts | N/A | LIM protein |

| FBgn0260463 | Unc-115b | Q8INN7 A0A126GUR5 | N/A | Amnioserosa, Mucsle, Mesoderm, Head | LIM protein |

| FBgn0003090 | Pk | A1Z6W3, Q3YNB2 | N/A | N/A | LIM protein |

| FBgn0034223 | Tes | A1ZAT5 | Zygotic | N/A | LIM protein |

| FBgn0041789 | Pax | Q9BPQ9, Q966T5, Q2PDT4 Q9VIX2 | N/A | Cardiac mesoderm, Muscle system | LIM-Only |

| FBgn0063485 | Lasp | Q8I7C3 M9NDA6 M9NFH3 | CNS, Ectoderm | CNS | LIM protein |

| FBgn0283712 | LIMK1 | Q8IR79, E1JJM7 | Ubiquitous | N/A | LIM protein |

| FBgn0250819 | CG33521 | H9XVQ0 | Muscle system, | Muscle system | LIM-Only |

| FBgn0261565 | Lmpt | Q8IQQ3, Q8MYZ5, M9MRX0, Q9VVB5 | Intestine, Muscles, PNS, Ring gland, Sensory system, Lymph Glands, | Muscle system, Tracheal system, Amnioserosa, Mesoderm | LIM protein |

| FBgn0026411 | Lim1 | Q9V472 | Brain, CNS, Gut, Tracheal system, | Hypopharynx, Vent nerve cord, | LIM-HD |

| FBgn0002023 | Lim3 | Q9VJ02, M9PD53 | CNS, Ventral nerve cord | Head | LIM-HD |

| FBgn0265598 | Beadex | Q8IQX7, M9PI02, M9PHX4 | Intestine, Brainlobes, Ovary, Testis | N/A | LIM-Only |

| FBgn0267978 | Ap | P29673 | Mesoderm, Brain, CNS, Tracheal system, Lymph Glands, Segmented pattern | N/A | LIM-HD |

| FBgn0050147 | Hil | Q0E908 | N/A | N/A | LIM protein |

| FBgn0014863 | Mlp84B | Q24400 | N/A | Muscle system | LIM-Only |

| FBgn0051624 | CG31624 | Q2XYF8 | N/A | N/A | LIM-Only |

| FBgn0085354 | CG34325 | Q9VXC1 | Ubiquitous | N/A | LIM-Only |

| FBgn0050178 | CG30178 | Q8MLQ2 | Ubiquitous | N/A | LIM-Only |

| FBgn0020249 | Stck | Q8IGP6 | Ubiquitous | Visceral muscle | LIM protein |

| FBgn0011642 | Zyx | Q8T0F5 Q9N675 | Mesoderm | N/A | LIM-Only |

| FBgn0051988 | CG31988 | Q8T0V8 | N/A | N/A | LIM-Only |

| FBgn0051624 | CG31624 | Q2XYF8 | N/A | N/A | LIM-Only |

| FBgn0039055 | Rassf | Q9VCQ7 | N/A | N/A | LIM protein |

| FBgn0003896 | Tup | Q9VJ37 | Amnioserosa, API, Foregut, Head, Tracheal system, Muscles, Dorsal vessel | Amnioserosa, Leading edge cell, CNS, Dorsal epidermis, Embryonic brain, sophagus, Foregut, Stomatogastric | LIM-HD |

| FBgn0032196 | CG5708 | Q9VL21 | N/A | NA | LIM-Only |

| FBgn0036274 | CG4328 | Q9VTW3 | Ventral nerve, cord,CNS | NA | LIM-HD |

| FBgn0052105 | Lmx1a | Q9VTW5 | Ventral nerve cord,CNS | CNS, Trunk mesoderm, Longitudinal visceral mesoderm | LIM-HD |

| FBgn0030530 | Jub | Q9VY77 | N/A | N/A | LIM-Only |

| FBgn0265597 | Rad | X2JBI1X2JDH0 | N/A | N/A | LIM protein |

Proteins containing the LIM domain in Drosophila melanogaster were predicted by using the SMART. We found there are a total of 36 genes encoding 75 proteins with the LIM domain in Drosophila melanogaster. These genes play roles in a variety of biological functions, including muscle, heart, lymph gland, nervous system, eye development, and leg morphogenesis, and so on. According to the characteristics of protein domains, LIM proteins were classified into three types, LIM protein types, LIM-only types, LIM-homeodomain (LIM-HD) types.

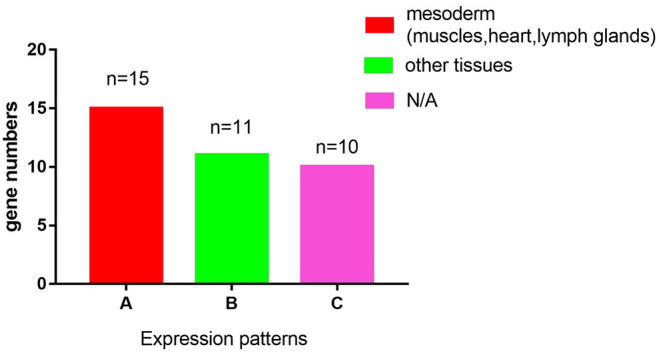

Figure 1.

A graphic overview of the expression patterns of the 36 LIM genes in Drosophila melanogaster. According to the FLY-FISH or FlyExpress databases, there are 15 LIM genes expressed in mesoderm including muscles, heart, or lymph glands (Columm A). It indicates that 11 LIM genes are expressed in other non- Columm A tissues (Columm B). The expression patterns of the remaining 10 LIM genes are unclear (Columm C).

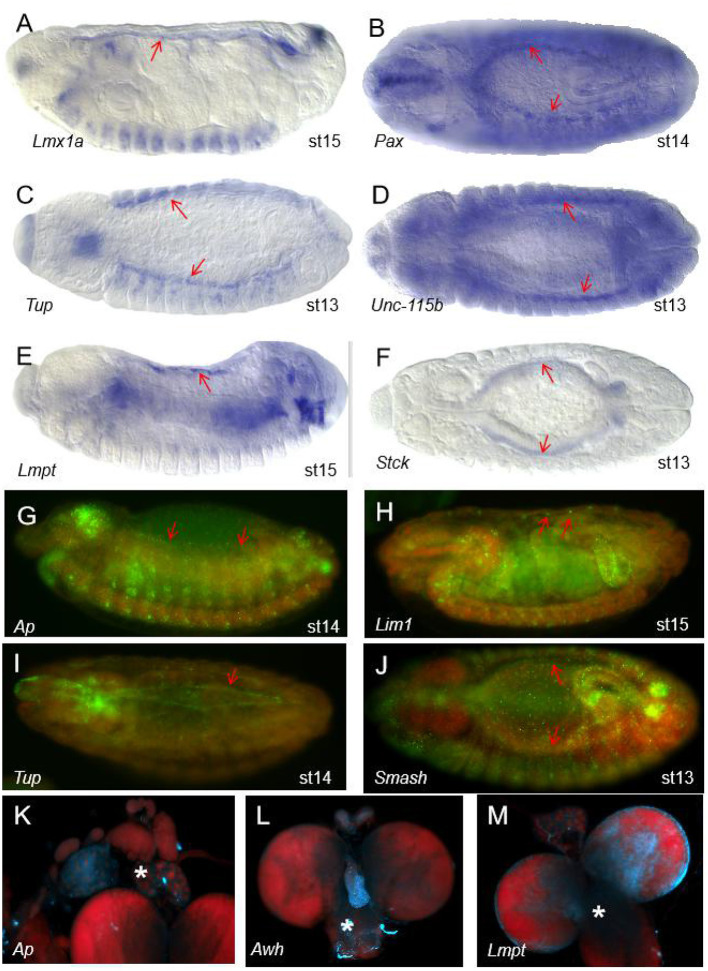

Figure 2.

The expression patterns of some of the 36 LIM genes in Drosophila melanogaster. (A–F) Expression patterns of some genes with the LIM domain in wild type (WT) Drosophila embryos from the FlyExpress (ISH) database. The red arrows represent the heart region of the fruit fly embryo. Embryos are at stage 13–15 of development. Lmx1a (A), Pax (B), Tup (C), Unc-115b (D), Lmpt (E), and Stck (F) are expressed in Drosophila heart tissue. (G–J) Expression patterns of some genes with the LIM domain in Drosophila embryos in the Fly-FISH database. The red arrows represent the heart region of the fruit fly embryo. Embryos are at stage 13–15 of development. Ap (G), Lim1 (H), Tup (I), and Smash (J) are expressed in Drosophila heart tissue. Embryo colors: Red/DNA, Green/RNA. (K–M) The area of the lymph glands in the anatomy. Expression patterns of some genes with the LIM domain in the third larvae of Drosophila in the Fly-FISH database. The white asterisk represents the lymph gland region of the fruit fly larvae. Ap (K), Awh (L), and Lmpt (M) are expressed in Drosophila lymph gland. Larval colors: Red/DNA, Blue/RNA.

LIM Homeodomain Transcription Factor tailup Is Required for Normal Heart and Hematopoietic Organ Formation in Drosophila

Fly LIM homeodomain transcription factor tailup (Tup), a homologous gene of Islet1 in vertebrate, belongs to LIM-HD type, expresses in all cardiac cells (CC) and pericardial cells (PC) of the heart tube as well as lymph glands hematopoietic organs (28–30), which is not in line with the data in Table 1, we think it didn't be detected, or the probes did not work in the two databases (FLY-FISH, and FlyExpress). In vertebrates, the homologous gene Islet1 is also a cardiac progenitor marker (31), and many of the heart formation processes are regulated by the transcription factor Islet1 (32). It is reported that, in Tup mutant fly embryos, heart tubes showed misaligned cardio-blasts and lost most lymph glands and pericardial cells (33). This indicated Tup participated in fly heart development. While irregular morphology of the heart with hypertrophied lymph glands has been observed when Tup was overexpressed in fly mesoderm (33). This indicated Tup also participated in fly hematopoietic organ formation. Tup is an entrant in the regulatory network controlling dorsal vessel morphogenesis and hematopoietic organ formation. Tup can be considered to be a main upstream regulator of genetic and cellular events controlling lymph gland formation (33). For example, it is reported that Tup was an upstream regulator of Hand in these developmental processes. Tup can recognize and bind to two DNA response sequences in the enhancer of the Hand, which has been proven to be essential for the lymph gland cells, pericardial cells, and cardiac cells (34). Also, Tup is a regulator of srp and odd, which play an essential role in hematopoietic progenitor cell specification (33, 35). Drosophila LIM-HD domain protein Tup was specifically expressed in heart lymph gland tissue and had a unique role in heart development. LIM-domain factors affiliated to cooperate with the adaptor snippet Chip/Ldb1 to form higher-order protein complexes to determine gene expression (36). In a word, Tup interacted with Chip/Ldb1 to regulate some ingenious factors, such as Even-skipped (Eve), Hand, and Odd, involved in cardiac cell specification and differentiation (37–40). As we known, the GATA factors pnr and srp directly activate Hand in cardioblasts, pericardial nephrocytes and hematopoietic progenitors, Hand is initially expressed weak and segmental in cardiac cells, but soon becomes strong in most cardioblasts and pericardial cells from embryo in stage13 to adult heart. The pattern expression of hand is controlled by a 513bp enhancer between exons 3 and 4 of the Hand gene, which contained DNA sequence with Tinman- and GATA-binding sites (41).

Due to the expression patterns and functions of Tup in fly heart, as well as some other LIM-HD type genes listed in the Table 1, which expressed in the mesoderm at early stage, it is implied that LIM-HD domain proteins might regulate the differentiation and specialization of cardiac progenitor cells in early cardiac development, and interacte with Chip/Ldb1 to determine normal heart and hematopoietic organ formation in Drosophila (36). Also, some genes involved in heart development could be the targets of LIM-HD domain proteins.

Mlp84B, a Muscle LIM Protein, Is Essential for Cardiac Function in Drosophila

Mlp84B, a muscle LIM protein (MLP), belongs to the LIM-only type, locates at the Z-disc of sarcomeres (42, 43). The human MLP gene has been represented to be a key player in the stretch-sensing response, and its mutant is associated with hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy (44). In mice, the LIM domain protein CRP2, a Drosophila Mlp84B homolog, expressed in the vascular system, especially in smooth muscle cells. CRP2 knock-out mice exhibit some mild hypertrophy phenotype in their cardiac ultrastructure (45). Mlp84B, co-localizes with α-actinin in the heart from late embryonic stages to adulthood in Drosophila, and is essential for Drosophila lifespan and cardiac function (46, 47). The shortened lifespan was found in Mlp84B knockout flies, and with a dramatically decreased lifespan in knockdown flies by the cardiac driver tinCΔ4-Gal4, which are due to the role of Mlp84B in cardiac function. Mlp84B mutant flies appeared bradycardia and heart rhythm abnormalities without obvious organic phenotype (46). We believe that MLP proteins may play a critical role in the differentiation of cardiac muscle and contribute to proper cardiac function by directing cardiac muscle structure development. It is known that dMEF2, an invertebrate member of the Myocyte Enhancer Factors family of vertebrate myocyte, has MADS-box and MEF2 domains which assisted its dimerization and DNA binding, plays an essential role in muscle differentiation (48). Due to the six dMEF2 binding sites found in the Mlp84B locus, dMEF2 is necessary for the expression of Mlp84B in all the muscle tissues including skeletal, cardiac, and smooth muscles (48). Collectively, it suggested that Mlps may be targets of dMEF2 proteins that contribute to cardiomyocyte differentiation and function. We hypothesized that LIM domain genes expressed in muscle tissue are likely regulated by MEF2, which determines the differentiation of the three types of muscle cells. We predicted LIM genes expressed in heart muscle tissue, such as Mlp60A, Smash, Lmpt, etc (see Table 1), might be essential for the differentiation of cardiomyocyte.

The Drosophila radish Gene Is Required for Cardiac Pacemaker

The Drosophila radish (Rad) gene is required for cardiac function (49). It is known that Rad, encoding a protein with a POZ domain and a Rap GTPase activating protein domain, involved in regulating anesthesia-resistant memory and heart contraction function (49, 50). Interestingly, we found that Rad is also a member of the LIM protein family, based on the predictions of SMART tool (Table 1). We also analyzed the domains within Drosophila melanogaster protein Radish, the LIM domain was located at positions 568 to 622 amino acids (Figure 3). Conveniently, there is no expression data presented for Rad in Table 1, further studies are needed to confirm whether it is expressed in heart tissue. The exceptional Rad mutants, which effected memory and retention, substantially lessened heart rate and rhythms. The heart rate of Rad mutants was significantly lower than that of wild mutants at different temperatures (49). Besides, these mutants were insensitive to both serotonin and norepinephrine. In a word, Rad mutations were closely associated with bradycardia in fly. Its effect on heart function is likely mediated via neurotransmitter release (49). While the molecular mechanism by which the Rad regulates heart function remained ambiguous, Rad likely effects the heart modulatory pathway (49). We knew that muscle LIM protein Mlp84B, mainly located at the Z-line boundary, maintained the structural integrity of muscles by interacting with α-actinin, and D-titin was essential for cardiac function (47, 51). We hypothesized the LIM proteins, such as Rad, if it is expressed in the heart muscle tissue, it maybe also interacted with the modular protein present in muscles to regulate the structure of the heart muscles and thus affected the function of the heart. So LIM proteins not only regulate cardiac development but also affect cardiac function.

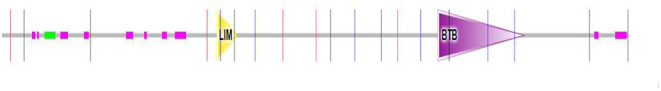

Figure 3.

Domains within Drosophila melanogaster protein Radish. Yellow triangle box represents the LIM domain region, the LIM domain of Radish was located at positions 568 to 622 amino acids.

Beadex, a Drosophila Homolog of LIM Domain Only 2 (LMO2), Functions in Hematopoiesis

The lymph organ, which produces the hemolymph cells, is derived from the cardiac progenitors, some of the genes that affect heart development also involved in hematopoiesis. Tup, a regulator of srp and odd expression in lymph gland cells and pericardial cells (33, 35), is a typical example. So we think that in addition to affecting heart function and heart development, LIM proteins also regulate blood cell formation in Drosophila. There are three classes of blood cells in Drosophila: plasmatocytes, lamellocytes, and crystal cells (17, 52). The development of crystal cell, a non-phagocytic cell, is similar to that of vertebrate erythroid in the early phase (53). In Table 1, we found that Beadex, a Drosophila homolog of LIM domain only 2 (LMO2), is expressed in hemocytes, and was reported to effect the numbers of crystal cells after their specification (54). Morever, in vertebrate, LMO2 is necessary for the emergence of hematopoietic stem cells during ontogeny and angiogenesis by modeling a complex with the LIM domain-binding protein 1, and binding to the E-box and GATA transcription factors (55, 56). In fly, overexpression of Beadex in crystal cell lineage leading to a dramatic increase in the number of crystal cells. Meanwhile, a knockdown of Beadex resulted in a significant decrease in the number of crystal cells (3). This indicated Beadex is involved in the proliferation of blood cells in fly. Drosophila GATA factor pannier (Pnr), a known interacting colleague of Beadex. Gain of function (GOF) of both pnr and Beadex in fly, the crystal cell counts were consistent with that of pnr GOF alone, and GOF of Beadex and loss of function (LOF) of pnr in fly, the crystal cell counts were similar to that of pnr LOF alone, therefore, the misexpression of pnr masked the effect of Beadex on the number of crystal cells. So, pnr has genetic interactions with Beadex during the development of crystal cell (3, 57, 58). Pnr, as a downstream molecular, can bind to cofactor U-shaped (Ush) to inhibite crystal cell development (3, 59). Thus, pnr is also supposed to interfere in the development of crystal cells. That is to denote, LIM proteins might contribute to hematopoietic development through the GATA transcription factor. According to the Fly-FISH database, we also found that some LIM genes expressed in the lymph glands of Drosophila (Table 1 and Figures 2K–M). Combined with the study on the role of Beadex in the hematopoietic system in Drosophila, we speculate that LIM proteins may also have a role in the hematopoietic system of Drosophila.

Perspectives

This review summarized the role and molecular mechanisms of LIM transcription factors of Drosophila during cardiovascular development. The Drosophila melanogaster has emerged as a powerful model for studying heart development and cardiac diseases, as well as an excellent model for human cardiac development and diseases (17, 52). LIM domains are identified in diverse groups of proteins with a wide variety of biological functions, including gene expression regulation, cell fate determination, cytoskeleton organization, tumor formation, and heart development (18–20). Just as LIM related factors arise to be conserved in the arrangement of cardiac development and physiology in the animal kingdom from fly to human.

Through analysis of the bioinformatics database of Drosophila LIM domain transcription factors, a total of 36 genes encoding 75 proteins with the LIM domain in Drosophila melanogaster were found. We divided LIM proteins into three categories, LIM protein type, LIM-only type, and LIM-HD type, according to the characteristics of protein domains. LIM domain proteins can be either transcription factors or structural proteins to regulate cardiac and hematopoietic morphogenesis. As a transcription factor, such as tup, can recognize and bind to two DNA response sequences in the enhancer of the Hand, and act as a regulator of srp and odd to determines the differentiation of lymph gland cells, cardiac cells, and pericardial cells. As a structural protein, such as Mlp84B, is the cytoskeletal protein, directly affects muscle structure and function. From Fly-FISH and FlyExpress (23–27), we knew that some of LIM domain mRNAs were located in lymph glands, muscles system, and circulatory system, which inferred that LIM domain genes might have roles in cardiac and hematopoietic morphogenesis. It would be attractive to dissect whether it exists a probable LIM code for the cycle of different cell fates in cardiac and hematopoietic tissues, and this hypothesis needs to be better supported in future studies. In this review, we aspired to proposed a research direction that the LIM domain genes may play important roles in cardiac development and hematopoiesis. Cardiomyocytes are a type of muscle cells, and dMef2 regulates the differentiation of cardiomyocytes, therefore, we hypothesized that one possible mechanism is that LIM domain genes can act as the targets of dMef2 in heart tissue, regulate the differentiation of cardiomyocytes, interact with Chip/Ldb1 to determine normal heart and hematopoietic organ formation in Drosophila, and participate in hematopoietic development through GATA transcription factor.

Author Contributions

MS and QZ wrote and edited the manuscript together. MT and TJ generated the figures and table together. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Kumar S. for permitting us to use the images in FlyExpress and Henry Krause for permitting us to use the images in Fly-FISH.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (No.2020JJ5479), Hunan Provincial Department of Education Project (No.19C1604), Doctoral Research Foundation of University of South China (No.190XQD022), and University Student Innovation Project of University of South China (No.X2019153).

References

- 1.Frasch M. Genome-wide approaches to Drosophila heart development. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. (2016) 3:20. 10.3390/jcdd3020020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodmer R, Venkatesh T. Heart development in Drosophila and vertebrates: conservation of molecular mechanisms. Dev Genet. (1998) 22:181–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chatterjee A, Aavula K, Nongthomba U. Beadex, a homologue of the vertebrate LIM domain only protein, is a novel regulator of crystal cell development in Drosophila melanogaster. J Genet. (2019) 98:107. 10.1007/s12041-019-1154-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berrak U, Kuchuan C, Hugo JB. Drosophila tools and assays for the study of human diseases. Dis Model Mech. (2016) 9:235–44. 10.1242/dmm.023762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodmer R. The gene tinman is required for specification of the heart and visceral muscles in Drosophila. Development. (1993) 118:719–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cannon L, Bodmer R. Genetic manipulation of cardiac ageing. J Physiol. (2016) 594:2075–83. 10.1113/JP270563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klinedinst SL, Bodmer R. Gata factor Pannier is required to establish competence for heart progenitor formation. Development. (2003) 130:3027−38. 10.1242/dev.00517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lockwood WK, Bodmer R. The patterns of wingless, decapentaplegic, and tinman position the Drosophila heart. Mech Dev. (2002) 114:13–26. 10.1016/S0925-4773(02)00044-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rotstein B, Paululat A. On the morphology of the Drosophila heart disease. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. (2016) 3:15. 10.3390/jcdd3020015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crossley A. The ultrastructure and function of pericardial cells and other nephrocytes in an insect: calliphora erythrocephala. Tissue Cell. (1972) 4:529–60. 10.1016/S0040-8166(72)80029-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Villanueva J, Livelo C, Trujillo A, Chandran S, Woodworth B, Andrade L, et al. Time-restricted feeding restores muscle function in Drosophila models of obesity and circadian-rhythm disruption. Nat Commun. (2019) 10:2700. 10.1038/s41467-019-10563-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramond E, Meister M, Lemaitre B. From embryo to adult: hematopoiesis along the Drosophila life cycle. Dev Cell. (2015) 33:367–8. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koranteng F, Cha N, Shin M, Shim J. The role of lozenge in Drosophila hematopoiesis. Mol Cells. (2020) 43:114–20. 10.14348/molcells.2019.0249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mandal L, Banerjee U, Hartenstein V. Evidence for a fruit fly hemangioblast and similarities between lymph-gland hematopoiesis in fruit fly and mammal aorta-gonadal-mesonephros mesoderm. Nature genetics. (2004) 36:1019–23. 10.1038/ng1404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banerjee U, Girard JR, Goins LM, Spratford CM. Drosophila as a genetic model for hematopoiesis. Genetics. (2019) 211:367–417. 10.1534/genetics.118.300223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans C, Hartenstein V, Banerjee U. Thicker than blood: conserved mechanisms in Drosophila and vertebrate hematopoiesis. Dev Cell. (2003) 5:673–90. 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00335-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crozatier M, Vincent A. Drosophila: a model for studying genetic and molecular aspects of haematopoiesis and associated leukaemias. Dis Model Mech. (2011) 4:439–45. 10.1242/dmm.007351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freyd G, Kim S, Horvitz H. Novel cysteine-rich motif and homeodomain in the product of the Caenorhabditis elegans cell lineage gene lin-11. Nature. (1990) 344:876–9. 10.1038/344876a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karlsson O, Thor S, Norberg T, Ohlsson H, Edlund T. Insulin gene enhancer binding protein Isl-1 is a member of a novel class of proteins containing both a homeo- and a Cys-His domain. Nature. (1990) 344:879–82. 10.1038/344879a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang Y, Bradford WH, Zhang J, Sheikh F. Four and a half LIM domain protein signaling and cardiomyopathy. Biophys Rev. (2018) 10:1073–85. 10.1007/s12551-018-0434-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mende DR, Letunic I, Huerta-Cepas J, Li SS, Forslund K, Sunagawa S, et al. proGenomes: a resource for consistent functional and taxonomic annotations of prokaryotic genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. (2017) 45:D529–34. 10.1093/nar/gkw989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finn RD, Attwood TK, Babbitt PC, Bateman A, Bork P, Bridge AJ, et al. InterPro in 2017-beyond protein family and domain annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. (2017) 45:D190–9. 10.1093/nar/gkw1107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lécuyer E, Yoshida H, Parthasarathy N, Alm C, Babak T, Cerovina T, et al. Global analysis of mRNA localization reveals a prominent role in organizing cellular architecture and function. Cell. (2007) 131:174–87. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilk R, Hu J, Blotsky D, Krause H. Diverse and pervasive subcellular distributions for both coding and long noncoding RNAs. Genes Dev. (2016) 30:594–609. 10.1101/gad.276931.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Konikoff C, Karr T, McCutchan M, Newfeld S, Kumar S. Comparison of embryonic expression within multigene families using the FlyExpress discovery platform reveals more spatial than temporal divergence. Dev Dyn. (2012) 241:150–60. 10.1002/dvdy.22749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar S, Boccia K, McCutchan M, Ye J. Exploring spatial patterns of gene expression from fruit fly embryogenesis on the iPhone. Bioinformatics. (2012) 28:2847–8. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar S, Konikoff C, Van Emden B, Busick C, Davis K, Ji S, et al. FlyExpress: visual mining of spatiotemporal patterns for genes and publications in Drosophila embryogenesis. Bioinformatics. (2011) 27:3319–20. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boukhatmi H, Schaub C, Bataillé L, Reim I, Frendo J, Frasch M, et al. An Org-1-Tup transcriptional cascade reveals different types of alary muscles connecting internal organs in Drosophila. Development. (2014) 141:3761–71. 10.1242/dev.111005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cai C, Liang X, Shi Y, Chu P, Pfaff S, Chen J, et al. Isl1 identifies a cardiac progenitor population that proliferates prior to differentiation and contributes a majority of cells to the heart. Dev Cell. (2003) 5:877–89. 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00363-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zmojdzian M, Jagla K. Tailup plays multiple roles during cardiac outflow assembly in Drosophila. Cell Tissue Res. (2013) 354:639–45. 10.1007/s00441-013-1644-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foo KS, Lehtinen ML, Leung CY, Lian X, Xu J, Keung W, et al. Human ISL1(+) ventricular progenitors self-assemble into an in vivo functional heart patch and preserve cardiac function post infarction. Mol Ther. (2018) 26:1644–59. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hatzistergos KE, Durante MA, Valasaki K, Wanschel ACBA, William Harbour J, Hare JM. A novel cardiomyogenic role for Isl1+ neural crest cells in the inflow tract. Sci Adv. (2020) 6:eaba9950. 10.1126/sciadv.aba9950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tao Y, Wang J, Tokusumi T, Gajewski K, Schulz R. Requirement of the LIM homeodomain transcription factor tailup for normal heart and hematopoietic organ formation in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol. (2007) 27:3962–9. 10.1128/MCB.00093-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zaffran S, Reim I, Qian L, Lo P, Bodmer R, Frasch M. Cardioblast-intrinsic Tinman activity controls proper diversification and differentiation of myocardial cells in Drosophila. Development. (2006) 133:4073–83. 10.1242/dev.02586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sorrentino R, Gajewski K, Schulz R. GATA factors in Drosophila heart and blood cell development. Semin Cell Dev Biol. (2005) 16:107–16. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Franz A, Shlyueva D, Brunner E, Stark A, Basler K. Probing the canonicity of the Wnt/Wingless signaling pathway. PLoS Genet. (2017) 13:e1006700. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bronstein R, Segal D. Modularity of CHIP/LDB transcription complexes regulates cell differentiation. Fly. (2011) 5:200–5. 10.4161/fly.5.3.14854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caputo L, Witzel HR, Kolovos P, Cheedipudi S, Looso M, Mylona A, et al. The Isl1/Ldb1 complex orchestrates genome-wide chromatin organization to instruct differentiation of multipotent cardiac progenitors. Cell Stem Cell. (2015) 17:287–99. 10.1016/j.stem.2015.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Navascués J, Modolell J. The pronotum LIM-HD gene tailup is both a positive and a negative regulator of the proneural genes achaete and scute of Drosophila. Mech Dev. (2010) 127:393–406. 10.1016/j.mod.2010.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jin H, Stojnic R, Adryan B, Ozdemir A, Stathopoulos A. Frasch M. Genome-wide screens for in vivo Tinman binding sites identify cardiac enhancers with diverse functional architectures. PLoS Genet. (2013) 9:e1003195. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Han Z, Olson E. Hand is a direct target of Tinman and GATA factors during Drosophila cardiogenesis and hematopoiesis. Development. (2005) 132:3525–36. 10.1242/dev.01899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geier C, Perrot A, Ozcelik C, Binner P, Counsell D, Hoffmann K, et al. Mutations in the human muscle LIM protein gene in families with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. (2003) 107:1390–5. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000056522.82563.5F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hobert O, Westphal H. Functions of LIM-homeobox genes. Trends Genet. (2000) 16:75–83. 10.1016/S0168-9525(99)01883-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mohapatra B, Jimenez S, Lin J, Bowles K, Coveler K, Marx J, et al. Mutations in the muscle LIM protein and alpha-actinin-2 genes in dilated cardiomyopathy and endocardial fibroelastosis. Mol Genet Metab. (2003) 80:207–15. 10.1016/S1096-7192(03)00142-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sagave JF, Moser M, Ehler E, Weiskirchen S, Stoll D, Günther K, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse Csrp2 gene encoding the cysteineand glycine-rich LIM domain protein CRP2 result in subtle alteration of cardiac ultrastructure. BMC Developmental Biology. (2008) 8:80. 10.1186/1471-213X-8-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mery A, Taghli-Lamallem O, Clark KA, Beckerle MC, Wu X, Ocorr K, et al. The Drosophila muscle LIM protein, Mlp84B, is essential for cardiac function. J Exp Biol. (2008) 211:15–23. 10.1242/jeb.012435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clark K, Kadrmas J. Drosophila melanogaster muscle LIM protein and alpha-actinin function together to stabilize muscle cytoarchitecture: a potential role for Mlp84B in actin-crosslinking. Cytoskeleton. (2013) 70:304–16. 10.1002/cm.21106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stronach BE, Renfranz PJ, Lilly B, Beckerle MC. Muscle LIM proteins are associated with muscle sarcomeres and require dMEF2 for their expression during Drosophila myogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. (1999) 10:2329–42. 10.1091/mbc.10.7.2329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson E, Sherry T, Ringo J, Dowse H. Modulation of the cardiac pacemaker of Drosophila: cellular mechanisms. J Comp Physiol B. (2002) 172:227–36. 10.1007/s00360-001-0246-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Folkers E, Drain P, Quinn W. Radish, a Drosophila mutant deficient in consolidated memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1993) 90:8123–7. 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clark K, Bland J, Beckerle M. The Drosophila muscle LIM protein, Mlp84B, cooperates with D-titin to maintain muscle structural integrity. J Cell Sci. (2007) 120:2066–77. 10.1242/jcs.000695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Waltzer L, Gobert V, Osman D, Haenlin M. Transcription factor interplay during Drosophila haematopoiesis. Int J Dev Biol. (2010) 54:1107–15. 10.1387/ijdb.093054lw [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vlisidou I, Wood W. Drosophila blood cells and their role in immune responses. FEBS J. (2015) 282:1368–82. 10.1111/febs.13235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu C, Yuan M, Gao Y, Sun W. LMO2 functional and transcriptional regulatory profiles in hematopoietic cells. Leuk Res. (2018) 75:11–4. 10.1016/j.leukres.2018.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Valge-Archer V, Forster A, Rabbitts TH. The LMO1 and LDB1 proteins interact in human T cell acute leukaemia with the chromosomal translocation t(11;14)(p15;q11). Oncogene. (1998) 17:3199–202. 10.1038/sj.onc.1202353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Osada H, Grutz G, Axelson H, Forster A, Rabbitts TH. Association of erythroid transcription factors: complexes involving the LIM protein RBTN2 and the zinc-finger protein GATA1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1995) 92:9585–9. 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Muratoglu S, Hough B, Mon S, Fossett N. The GATA factor serpent cross-regulates lozenge and u-shaped expression during Drosophila blood cell development. Dev Biol. (2007) 311:636–49. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Minakhina S, Tan W, Steward R. JAK/STAT and the GATA factor Pannier control hemocyte maturation and differentiation in Drosophila. Dev Biol. (2011) 352:308–16. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.01.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haenlin M, Cubadda Y, Blondeau F, Heitzler P, Lutz Y, Simpson P, et al. Transcriptional activity of pannier is regulated negatively by heterodimerization of the GATA DNA binding domain with a cofactor encoded by the u-shaped gene of Drosophila. Genes Dev. (1997) 11:3096–108. 10.1101/gad.11.22.3096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]