Abstract

Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli are the leading cause of human gastroenteritis in the industrialized world and an emerging threat in developing countries. The incidence of campylobacteriosis in South America is greatly underestimated, mostly due to the lack of adequate diagnostic methods. Accordingly, there is limited genomic and epidemiological data from this region. In the present study, we performed a genome-wide analysis of the genetic diversity, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance of the largest collection of clinical C. jejuni and C. coli strains from Chile available to date (n = 81), collected in 2017–2019 in Santiago, Chile. This culture collection accounts for more than one third of the available genome sequences from South American clinical strains. cgMLST analysis identified high genetic diversity as well as 13 novel STs and alleles in both C. jejuni and C. coli. Pangenome and virulome analyses showed a differential distribution of virulence factors, including both plasmid and chromosomally encoded T6SSs and T4SSs. Resistome analysis predicted widespread resistance to fluoroquinolones, but low rates of erythromycin resistance. This study provides valuable genomic and epidemiological data and highlights the need for further genomic epidemiology studies in Chile and other South American countries to better understand molecular epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance of this emerging intestinal pathogen.

Author summary

Campylobacter is the leading cause of bacterial gastroenteritis worldwide and an emerging and neglected pathogen in South America. In this study, we performed an in-depth analysis of the genome sequences of 69 C. jejuni and 12 C. coli clinical strains isolated from Chile, which account for over a third of the sequences from clinical strains available from South America. We identified a high genetic diversity among C. jejuni strains and the unexpected identification of clade 3 C. coli strains, which are infrequently isolated from humans in other regions of the world. Most strains harbored the virulence factors described for Campylobacter. While ~40% of strains harbored mutation in the gyrA gene described to confer fluoroquinolone resistance, very few strains encoded the determinants linked to macrolide resistance, currently used for the treatment of campylobacteriosis. Our study contributes to our knowledge of this important foodborne pathogen providing valuable data from South America.

Introduction

Campylobacteriosis caused by Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli has emerged as an important public health problem and is the most common bacterial cause of human gastroenteritis worldwide [1,2]. It is usually associated with a self-limiting illness characterized by diarrhea, nausea, abdominal cramps and bloody stools [1]. Nevertheless, extraintestinal manifestations might cause long-term complications such as Miller-Fisher or Guillain-Barré syndrome [1]. Despite the self-limiting course, certain populations such as children under 5 years of age, elderly patients, and immunocompromised patients might suffer severe infections and require antimicrobial treatment [3]. In this context, the World Health Organization (WHO) has included Campylobacter as a high priority pathogen due to the worldwide emergence of strains with high level of fluoroquinolone resistance [4].

In South America, there is limited data available on the prevalence of C. jejuni and C. coli in comparison to other enteric bacterial pathogens [1,5,6]. In Chile, the National Laboratory Surveillance Program of the Public Health Institute has reported an incidence rate of campylobacteriosis of 0.1 to 0.6 cases per 100,000 persons [7]. This is low compared to high-income countries, where incidence rates can reach two orders of magnitude higher [1]. Nevertheless, recent reports suggest that the burden of campylobacteriosis in Chile has been greatly underestimated due to suboptimal diagnostic protocols [7]. Indeed, a recent report suggests that Campylobacter spp. is emerging as the second most prevalent bacterial cause of human gastroenteritis in Chile [8].

Only few reports have analyzed the genetic diversity and antimicrobial resistance profiles of clinical human strains of Campylobacter in Chile [9–13]. Furthermore, these studies have either used a limited number of strains [13] or lacked the resolution provided by whole genome sequence-based typing methods [9–12]. Therefore, larger genomic epidemiology studies are needed in Chile and more broadly in South America.

We recently made available the whole genome sequences of 69 C. jejuni and 12 C. coli human clinical strains isolated from patients with an enteric infection visiting Clínica Alemana in Santiago, Chile, during a 2-year period (2017–2019) [14,15]. This represents the largest genome collection of clinical Campylobacter strains from Chile and one of the few collections available from South America. In the present study, we performed a genome-wide analysis of the genetic diversity, virulence potential, and antimicrobial resistance profiles of these strains. Importantly, we identified a high genetic diversity of both C. jejuni and C. coli strains, including 13 novel sequence types (STs) and alleles. Resistome analysis predicted widespread resistance to fluoroquinolones, but decreased resistance to tetracycline in comparison to the reported resistance from other regions of the world. In addition, we also describe differential distribution of virulence factors among strains, including plasmids and chromosomally encoded Type 6 and Type 4 Secretion Systems (T6SS and T4SS respectively). This work provides valuable epidemiological and genomic data of the diversity, virulence and resistance profiles of this neglected foodborne pathogen.

Methods

Genome data set, sequencing and reannotation

The genome sequence dataset analyzed in this study is listed in S1 Table and includes our recently published collection of human clinical strains of C. jejuni and C. coli from Chile [14,15]. We additionally sequenced C. jejuni strain CFSAN096303. This strain was sequenced as described in [14] using the NextSeq sequencer (Illumina) obtaining an estimated genome average coverage of 90X. The genome was assembled using the CLC Genomics Workbench v9.5.2 (Qiagen) following the previously used pipeline [14] and was deposited under accession number WXZQ01000000. FASTA files of all draft genomes were reordered to the reference genomes of the C. coli aerotolerant strain OR12 (accID GCF_002024185.1) and C. jejuni strain NCTC 11168 (accID GCF_000009085.1) using the Mauve Contig Mover (MCM) from the Mauve package [16]. The ordered genomes were annotated using Prokka [17] with the same reference files mentioned above and by forcing GenBank compliance. Draft genome sequence reannotations and sequence FASTA files are available as a supplementary dataset on Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3925206.

Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST) and core genome MLST (cgMLST) analysis

Genome assemblies were mapped against an MLST scheme based on seven housekeeping genes [18] and the 1,343-locus cgMLST scheme [19], using RIDOM SeqSphere software (Münster, Germany) [20]. The following GenBank (GCA) or RefSeq (GCF) genome assemblies were used as reference genomes: Campylobacter hepaticus HV10 (GCF_001687475.2), Campylobacter upsaliensis DSM 5365 (GCF_000620965.1), Campylobacter lari RM2100 (GCF_000019205.1), Campylobacter jejuni NCTC 11168 (GCF_000009085.1), C. jejuni doylei 269.97 (GCA_000017485.1), aerotolerant Campylobacter coli OR12 (GCF_002024185.1), Campylobacter coli BIGS0008 (GCA_000314165.1), Campylobacter coli 76339 (GCA_000470055.1), and Campylobacter coli H055260513 (GCA_001491555.1) were used as reference genomes. Phylogenetic comparison of the 81 Campylobacter genome sequences was performed using a neighbor-joining tree based on a distance matrix of the core genomes of all strains. Sequence Types (STs) and Clonal Complexes (CCs) were determined after automated allele submission to the Campylobacter PubMLST server [18]. Comparative cgMLST analysis with C. jejuni and C. coli clinical strains worldwide was performed with genomes available at the NCBI database. Annotations and visualizations were performed using iTOL v.4 [21].

Virulome, resistome and comparative genomic analysis

A local BLAST database was constructed using FASTA files of all sequenced genomes and the makeblastdb program from BLAST [22], which was screened for the nucleotide sequence of known pathogenicity genes using BLASTn (version 2.8.1) [22]. A 90% sequence length and 90% identity threshold were used to select positive matches. The FASTA file containing the nucleotide sequence of virulence genes screened can be found at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3925206. The C257T mutation in gyrA and mutations A2058C and A2059G in the genes for 23S RNA were searched manually by BLAST and sequences were aligned to the reference gene from strain Campylobacter jejuni ATCC 33560 using ClustalX [23]. Antimicrobial resistance genes were screened in each Campylobacter genome using the ABRicate pipeline [24], using the Resfinder [25], CARD [26], ARG-ANNOT [27] and NCBI ARRGD [28] databases. BLAST-based genome comparisons and visualization of genetic clusters were performed using EasyFig [29].

Pangenome and plasmid screening analysis

Annotated genome sequences were compared using Roary [30], setting a minimum percentage identity of 90% for BLASTp. Pangenome visualization was performed using roary_plots.py. Additionally, the file gene_presence_absence.csv produced by Roary was analyzed using a spreadsheet program to find genes that are shared by subgroups of isolates. Venn diagrams were constructed using the tool available at http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/. Plasmids screening was performed on FASTQ files using PlasmidSeeker [31], based on the default bacterial plasmid database. The inhouse database of known plasmids from C. coli or C. jejuni and the output table for the presence/abscence of gene content in the Roary analysis can be found in https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3925206. Pangenome BLAST analysis was performed using GView (https://server.gview.ca/) [32].

Results

Phylogenetic analysis of clinical Campylobacter strains

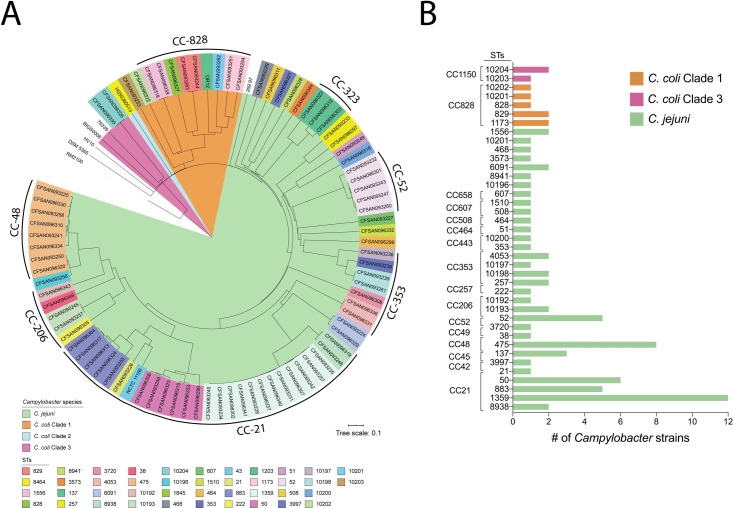

To gain insight into the diversity of Chilean clinical C. jejuni and C. coli strains, we performed a cgMLST analysis using the typing scheme recently developed by Cody et al. [19]. cgMLST analysis showed high genetic diversity among the 69 C. jejuni strains, as shown by the 14 CCs and 31 distinct STs identified (Fig 1). Almost 93% (n = 64) of the C. jejuni strains belonged to a previously described CC for this species. Among our strains, CC-21 was the most common (37.6%) and diverse (5 distinct STs) (Fig 1 and S1 Table). ST-1359 was the most prevalent ST of CC-21 (48%) and of all C. jejuni strains in this study (17.4%) (Fig 1 and S1 Table). In addition to CC-21, we identified high rates of CC-48 (13%) and CC-52 (7.3%). ST-475 from CC-48 was the second most prevalent ST (11.6%) identified (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Phylogenetic analysis of clinical C. jejuni and C. coli strains from Chile.

Phylogenetic tree is based on cgMLST performed with RIDOM SeqSphere+ and visualized by iTOL. STs are shown in colored boxes for each strain, and tree branches are color coded to highlight C. jejuni and C. coli strains from clades 1, 2 and 3. ST and CC frequency distribution of clinical C. jejuni and C. coli strains from this study are detailed in the right panel.

The cgMLST analysis of the 12 C. coli strains from our collection revealed that 83% (10/12) of the strains belonged to clade 1, while 17% (2/12) belonged to clade 3 and none to clade 2. Most clade 1 strains (8/10) belonged to CC-828 and included four previously described STs (828, 829, 1173, and 1556) and one novel ST (10201). Only one strain from clade 1 belonged to the usually common CC-1150 (strain CFSAN093253 from ST-10203), and another strain could not be assigned to any clonal complex (strain CFSAN096322 from ST-10202). Both clade 3 strains belonged to ST-10204.

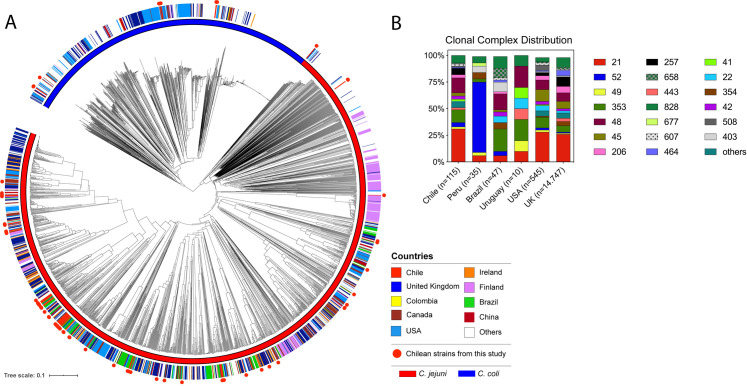

A global cgMLST analysis comparing our 81 Campylobacter genomes with other 1631 C. jejuni and 872 C. coli genomes available from the NCBI database was performed. The strains of our collections from Central Chile showed great diversity and did not group with any existing clusters (Fig 2A). The reconstructed phylogenetic trees and associated metadata of clinical strains from Chile in the global context of C. jejuni and C. coli sequenced strains can be interactively visualized on Microreact at https://microreact.org/project/VbEQsZtQD. Analysis of the genotype frequencies of clinical Campylobacter strains from Chile in comparison to other countries, showed a distribution of CCs more similar to countries from North America (United States) and Europe (United Kingdom) than from other countries from the region such as Peru, Brazil and Uruguay (Fig 2B).

Fig 2. Global cgMLST analysis of clinical C. jejuni and C. coli strains.

(A) Phylogenetic tree is based on cgMLST performed with RIDOM SeqSphere+ and visualized by iTOL. Countries of isolation are shown as colored strip and strains from this study are highlighted in red circles. A blue or red color strip highlights the species of each isolate. (B) Clonal complex frequency of clinical Campylobacter strains deposited in the pubMLST database separated per country of isolation.

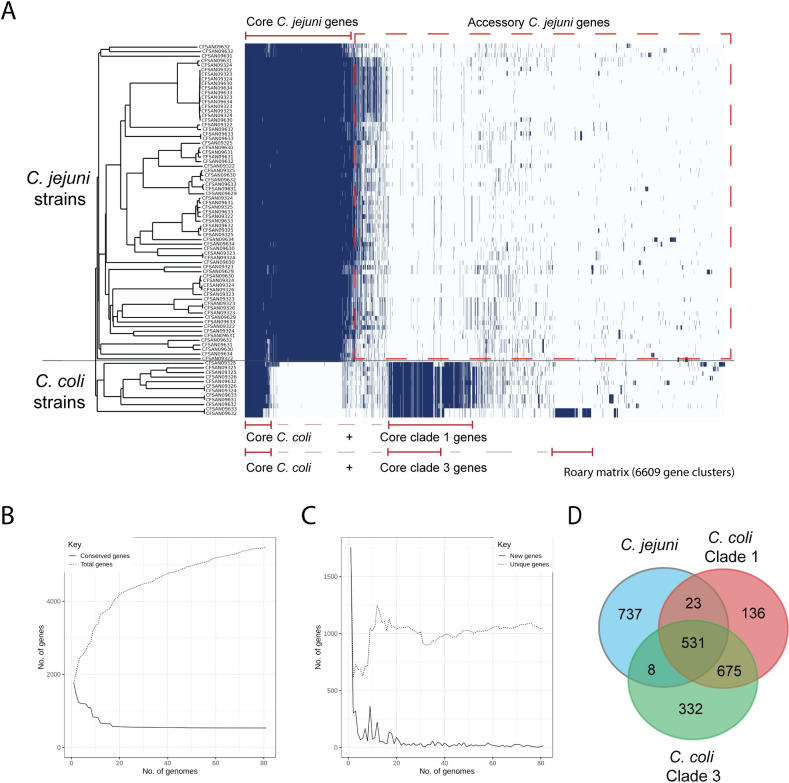

Pangenome analysis of Campylobacter strains

To identify the genetic elements that are shared and distinct among the Chilean C. jejuni and C. coli strains, we performed pangenome analysis of the 81 strains from both species (Fig 3). The analysis identified a pangenome of 6609 genes for both species and identified the core genes shared between C. jejuni and C. coli (531 genes) and the core genome of each species (1300 genes for C. jejuni and 1207 genes for C. coli). Our analysis showed an open pangenome as the number of genes increases with the addition of new genomes. The core genome decreased reaching a plateau at approximately 20 genomes (Fig 2C). The number of new and unique genes identified also reached a plateau after 20 genomes (Fig 2D).

Fig 3. Visualization of the pangenome of the C. jejuni and C. coli strains.

Pangenome analysis was performed using Roary. Core and accessory genomes are highlighted with red and black brackets, respectively. cgMLST phylogenetic tree of Fig 1A is shown on the left. B) The graph shows the number of genes in the core and pan genomes (continuous and discontinuous lines respectively) as increasing number of genomes are considered in random order. C) The number of genes unique to a genome (discontinuous line) and new genes not found in previously analyzed strains (continuous line) as increasing number of genomes are considered in random order. D) A Venn diagram highlighting the number of core genes present in C. jejuni and C. coli strains from clades 1 and 3 is shown on the right.

In addition, the analysis was able to identify the differences among the core and accessory genomes of C. coli strains from clade 1 and clade 3. C. coli strains from clade 1 harbored 340 core genes absent from clade 3 core genes, which in turn, harbored 159 core genes not present in clade 1 core genes (Fig 3). Further analysis with a higher number of C. coli sequences will be required in order to better estimate the core and accessory genomes of this specie. The estimated core genome for C. jejuni in our study (1300 genes) was close to the 1343 core genes identified in the development of the cgMLST scheme of C. jejuni [19] and in agreement with recent reports [33] (S2 Table). In addition, a significant variation in the accessory genome between C. jejuni and C. coli strains was identified, confirming the high genetic variability of Campylobacter. Accessory genes that are common to a particular cluster seem to contribute to modifications of carbohydrates and flagella as well as antibiotic resistance. There is also a proportion of genomes (around 28%) harboring T4SS and T6SS-related genes (see below).

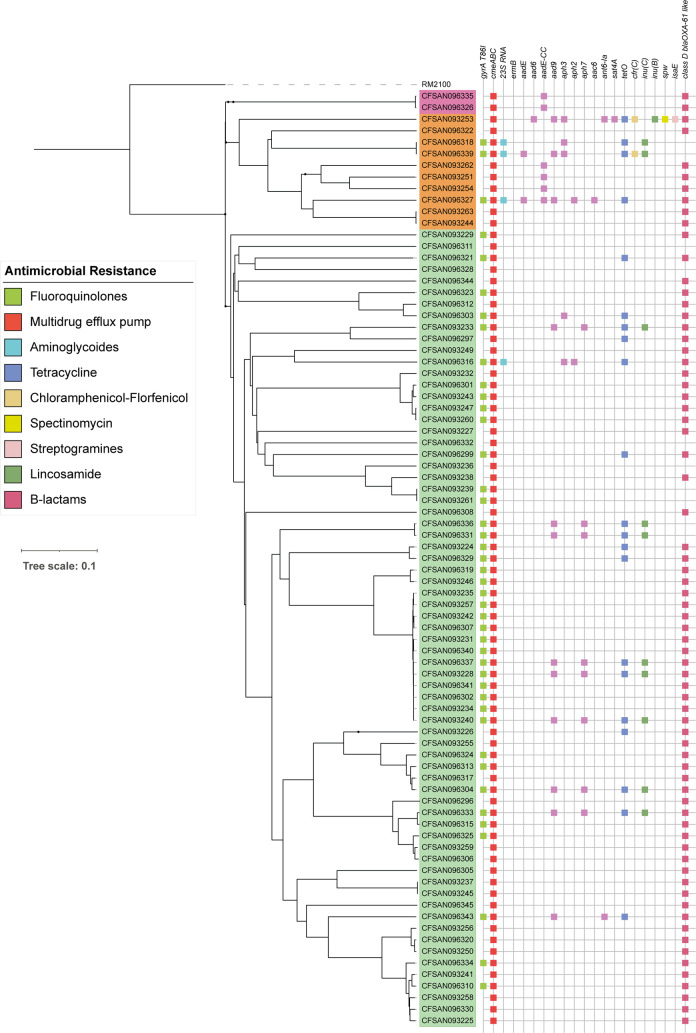

Genomic analysis of the resistome

To determine the resistome, we performed in silico analysis to identify genes associated with antimicrobial resistance (Fig 4) by screening each Campylobacter genome by means of the ABRicate pipeline [24] using the Resfinder, CARD, ARG-ANNOT and NCBI ARRGD databases. We additionally performed sequence alignments to identify point mutations in the gyrA and 23S rRNA genes. The cmeABC operon was present in all C. jejuni and C. coli strains analyzed. This operon encodes a common multidrug efflux pump characterized in different Campylobacter species, which mainly confers resistance to fluoroquinolones and in some cases to macrolides [34]. Additionally, the point mutation in the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) of the gyrA gene, leading to the T86I substitution in GyrA, was identified in 53.1% of the strains. This mutation confers high levels of resistance to fluoroquinolones [35].

Fig 4. Distribution of antimicrobial resistance genes.

Binary heatmaps show the presence and absence of antimicrobial resistance genes. Colored cells represent the presence of genes. cgMLST phylogenetic tree of Fig 1A is shown on the left. Strain names are color coded to highlight phylogenetic groups: C. jejuni strains (light green), C. coli clade 1 strains (orange) and C. coli clade 3 strains (magenta).

In contrast, a much lower fraction of the strains harbored resistance markers for other antimicrobials. The tetO gene, which confers tetracycline resistance in Campylobacter spp, was found in 22.2% of the strains [36]. Furthermore, only 4.94% of the strains carried the mutation of the 23S rRNA gene, which is associated to macrolide resistance [37]. The ermB gene was not detected. Finally, we also found a high proportion of strains (79%) harboring the blaOXA-61 gene among C. jejuni and C. coli strains. This genetic marker is associated with β-lactam resistance and has a high prevalence in Campylobacter strains worldwide [38].

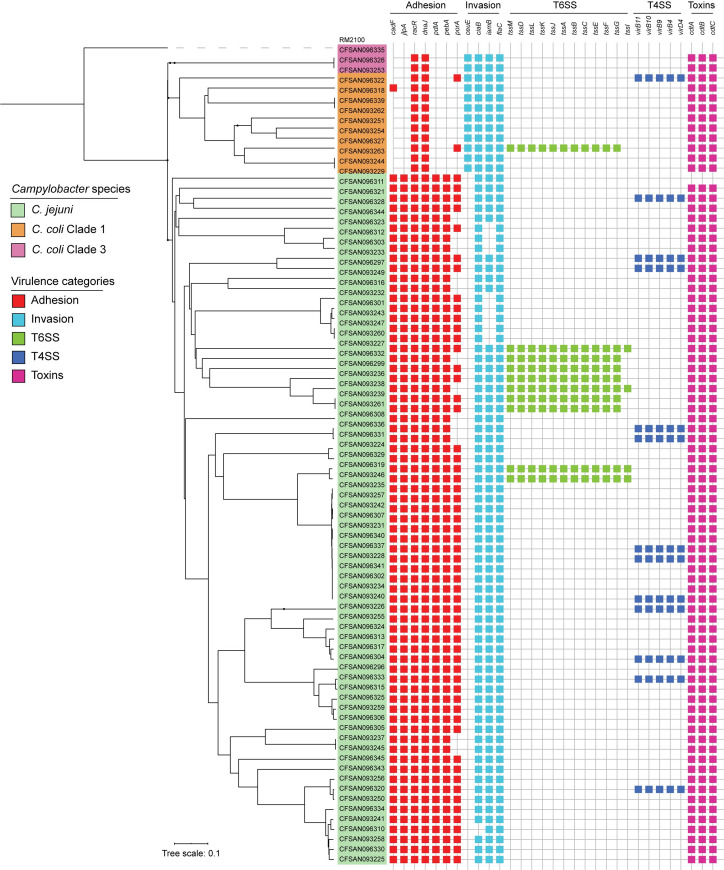

Presence and diversity of virulence gene content among Chilean Campylobacter strains

To determine the virulence gene content of the C. jejuni and C. coli strains, we first assembled a list of 220 potential virulence genes, including genes described in the Virulence Factor Database [39] and genes reported to contribute to the virulence of Campylobacter in the literature [40–43]. These genes were grouped into five distinct categories (adhesion and colonization, invasion, motility, secretion systems and toxins) and were used to screen each of the 81 genomes using BLASTn (Figs 5and S1, and S3 Table for the full list). Most of the described factors involved in adhesion and colonization (cadF, racR, jlpA, pdlA, dnaJ, aphC) were prevalent among the C. jejuni strains and were not associated with any particular STs (Fig 4, S3 Table).

Fig 5. Distribution of virulence-related genes.

Binary heatmaps show the presence and absence of virulence genes. Colored cells represent the presence of genes. cgMLST phylogenetic tree of Fig 1A is shown on the left. Strain names are color coded to highlight C. jejuni strains (green), C. coli clade 1 strains (orange) and C. coli clade 3 strains (purple).

The genes responsible for the production of the CDT toxin (cdtA, cdtB and cdtC) were also found in most strains of C. jejuni and in every tested C. coli strain. The cdtA and cdtB genes were not detected in the C. jejuni strain CFSAN093229. In contrast, the ciaB gene was identified in 98.7% of the C. jejuni strains (Fig 5). The product of this gene is involved in cecal colonization in chickens and in translocation into host cells in C. jejuni [44,45].

The major differences among C. jejuni strains were observed for genes located at the cps locus (Cj1413c -Cj1442) involved in capsule polysaccharide synthesis, the LOS locus (C8J1074-C8J1095) involved in lipooligosaccharide synthesis, a small set of genes in the O-linked flagellin glycosylation island (Cj1321-Cj1326) and the T6SS and T4SS gene clusters (Figs 5and S1, and S3 Table). Additionally, C. coli strains carried most of the genes known to be associated with invasiveness in C. jejuni, including the iamb, flaC and ciaB genes. Both C. coli clades also harbored some genes associated with other steps of infection such as the cdt toxin gene and most of the flagellar biosynthesis and chemiotaxis-related genes described for C. jejuni (S1 Fig). Its relevance in pathogenicity remains unclear [46].

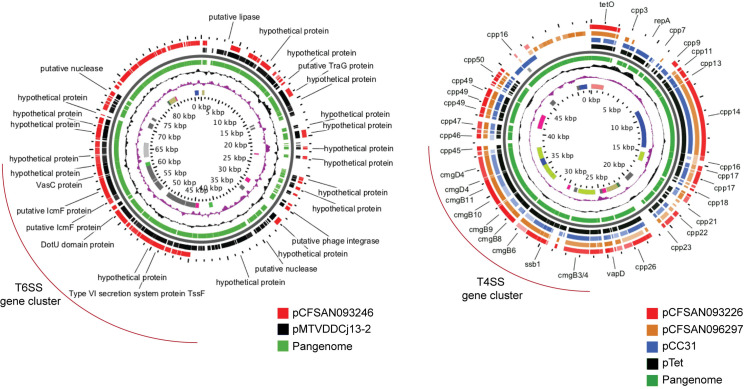

Distribution of the T6SS and T4SS gene clusters

Our analysis identified the T6SS gene cluster in nine C. jejuni strains and in one C. coli strain from clade 1 (Fig 5). As shown in S2 Fig, whenever present the genetic structure and the sequence identity of this cluster was highly conserved among C. jejuni and C. coli strains. For strains with genomes that were not closed, we were not able to confirm whether the tssI gene is located within the genetic context of the T6SS cluster, since it was not assembled in the same contig as the rest of the cluster. The Campylobacter T6SS gene cluster is often encoded within the CjIE3 conjugative element in the chromosome of C. jejuni [41], but it can also be found in plasmids [47,48]. Since most of our sequenced strains correspond to draft genome assemblies, we could not determine whether the T6SSs were plasmid or chromosomally encoded in most of them. However, we have closed the genomes of 2 of these strains (CFSAN093238 and CFSAN093227) [15]. In both of them, T6SS was inserted in the chromosomal CjIE3 element, while in strain CFSAN093246, it was plasmid-encoded. Sequence-based analysis of this plasmid showed a high degree of identity with plasmid pMTVDDCj13-2 (Fig 6), which encodes a complete T6SS gene cluster [48].

Fig 6.

Comparative genomic analysis of plasmids encoding T6SS (A) and T4SS (B) gene clusters. Pangenome BLAST analysis was performed using the Gview server. T6SS and T4SS gene clusters are highlighted in red brackets.

Genome analysis identified a T4SS gene cluster in 12 strains of C. jejuni and 1 strain of C. coli clade 1 (Fig 5). It harbored the 16 core genes and was correctly assembled in individual contigs in 11 strains, which allowed the analysis of the genetic context of the cluster. In each strain, the T4SS cluster had a conserved genetic structure (S2B Fig). One of the main differences between the T4SS gene clusters encoded in plasmids pTet and pCC31 is the sequence divergence of the cp33 gene [49]. While cp33 present in strain CFSAN096321 showed high identity with the gene harbored in the pTet plasmid, every other strain possessed high identity to the cp33 encoded in pCC31 plasmid. Both T4SS have been involved in bacterial conjugation and are not directly linked to the virulence of C. jejuni and C. coli strains [49]. As shown in Fig 6B, plasmids from closed genome strains CFSAN093226 and CFSAN096297 share significant similarity with both the pCC31 and pTET plasmids beyond the T4SS gene cluster. For all other strains, BLASTn analysis of each of our draft genome assemblies identified most of the plasmid genes found in pCFSAN093226, pCFSAN096297 and pTet-like plasmids, suggesting that all the T4SS gene clusters identified in these strains are encoded in plasmids as well.

Discussion

In South America, campylobacteriosis is an emerging and neglected foodborne disease. In countries such as Chile, even though Campylobacter is a notifiable enteric pathogen under active surveillance by public health agencies, routine stool culture–testing for this pathogen is rarely performed. This is partially explained by the high costs associated with the culture of this bacterium, including the need for special selective media and specific temperature and microaerophilic growth conditions [50]. As a consequence, there is limited genomic, clinical and epidemiological data available from the region, leaving an important knowledge gap in our understanding of the global population structure, virulence potential, and antimicrobial resistance profiles of clinical Campylobacter strains [1]. Here, we performed an in-depth genome analysis of the largest collection of clinical Campylobacter strains from Chile, which accounts for over 35% of the available genome sequences of clinical strains from South America.

cgMLST analysis provided insight into key similarities and differences in comparison to the genetic diversity reported for clinical Campylobacter strains worldwide. C. jejuni strains were highly diverse with CC-21 being the most common. CC-21 is the largest and most widely distributed CC, representing 18.9% of all C. jejuni strains submitted to the PubMLST database. The high prevalence of ST-1359 in our study was unexpected, since it is infrequent within the PubMLST database (0.06%, February 2020). However, ST-1359 has been recognized as a prominent ST in Israel [51]. ST-45, the second most prevalent ST worldwide (4.2%), was not identified among our strains. Previous reports from Chile identified four major CCs, including CC-21 (ST-50), CC-48 (ST-475), CC-257 (ST-257), and CC-353 (ST-353) [9,13]. Our study is consistent with these reports, except for the high prevalence of ST-1359. Interestingly, cgMLST analysis suggested that the ST-1359 strains of our study are highly similar (Fig 1). Although this similarity might indicate that these strains were part of a cluster, they harbored important differences in terms of isolation date and gene content, including the presence and/or absence of different antimicrobial resistance determinants and virulence genes (including plasmids). These data suggest that these strains most likely did not represent an outbreak but correspond to highly related strains with a possible common source.

Further studies are needed to determine if ST-1359 represents an emergent ST. Interestingly, it has recently been suggested that different geographical regions within Chile harbor distinct C. jejuni STs. Collado et al. described 14 STs that were exclusively identified in clinical C. jejuni strains isolated in the South of Chile (Valdivia) that were absent from the strains isolated from Central Chile (Santiago). Ten of these STs were also absent in our study supporting the notion that there is a differential distribution of clinically relevant STs in the country [9].

Our study also provided the first genome data of clinical C. coli strains from Chile. C. coli is divided into three genetic clades [52]. Clade 1 strains are often isolated from farm animals and human gastroenteritis cases while clade 2 and 3 strains are mainly isolated from environmental sources [52]. We showed that clade 1 strains from CC-828 were most prevalent, which is consistent with the worldwide distribution of this CC [52]. Interestingly, despite the lower amount of C. coli strains isolated in the 2-year period of our study (n = 12), we were able to identify strains from the uncommon clade 3. Therefore, larger genomic epidemiological studies are needed to determine the prevalence of clade 3 strains in Chile and South America.

Interestingly, the genotype frequencies from clinical Campylobacter strains from Chile differ from the frequencies observed in other countries from South America, including Peru, Brazil and Uruguay. Clonal complex distribution that was more similar to the frequencies observed in countries such as United States and United Kingdom (Fig 2B). While it is tempting to speculate that these differences reflect distinct epidemiological scenarios, it could very well be due to the limited data currently available from South America. It has been previously noted that there is currently insufficient epidemiological data from South America to provide an accurate assessment of the burden of campylobacteriosis in the region [1]. This is reflected in the data currently available in the pubMLST database. There is information regarding only 207 clinical Campylobacter isolates from South America in contrast to 14,747 isolates from the United Kingdom alone. This highlights the need for larger and more representative studies. Notably, two recent genomic epidemiology studies have added valuable data from both Peru and Brazil. Pascoe et al., sequenced and analyzed the genomes of 62 C. jejuni strains of a longitudinal cohort study of a semi-rural community near Iquitos in the Peruvian Amazon [6]. They found distinct locally disseminated genotypes and evidence of poultry as an important cause of transmission. In addition, Frazao et al., recently sequenced and analyzed a collection of 116 C. jejuni strains from Brazil. The collection spanned a period of 20 years and included strains isolated from animal, human, food and environmental sources [53], identifying high levels of resistance to ciprofloxacin and tetracycline and potential transmission from nonclinical sources.

Although most Campylobacter infections are self-limiting, antibiotics are indicated for patients with persistent and severe gastroenteritis, extraintestinal infections, or who are immunocompromised [1]. In Chile there is little information about antimicrobial resistance levels in Campylobacter spp and most studies are restricted to the Central and Southern regions of the country [9–12]. The high percentage of C. jejuni strains with a mutation of the gyrA gene, which confers quinolone resistance, is consistent with recent studies from Chile, reporting ciprofloxacin resistance of 30–60% [9,11–13]. One study reported that most resistant strains were associated with ST-48 [54], but we did not find an association to any particular STs. However, all of the strains belonging to ST-1359, the most frequent ST identified, harbored this mutation. Since fluoroquinolones are not the first choice antimicrobials for human campylobacteriosis, it has been suggested that high levels of resistance might be a consequence of their broad use in animal husbandry in Latin America [55]. These animal production practices might be responsible for the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes among Chilean Campylobacter strains.

Only few clinical strains harbored the mutation of the 23S rRNA gene, which confers macrolide resistance, [37]. Tetracycline resistance is widespread among Campylobacter strains worldwide [35]. Recently, the European Union reported high levels of resistance in C. jejuni strains (45.4%) and even higher levels in C. coli (68.3%). Tetracycline is especially used in the poultry industry worldwide [56], and might serve as an important reservoir for resistant strains [57]. Indeed, it was recently reported that 32.3% of C. jejuni strains isolated from poultry in Chile were resistant to tetracycline [12]. Our data are consistent with this report, as 22% of the clinical C. jejuni strains harbored the tetO gene. This potential emergence of resistance highlights the need for a permanent surveillance program to implement control measures for tetracycline usage in animal production.

The results of this study provide critical insights on the levels of antimicrobial resistance in Campylobacter, supporting previous reports that show high resistance against fluoroquinolones and tetracycline in the Chilean strains as well as high sensitivity to erythromycin [9,12]. Altogether, these data contribute to our knowledge of Campylobacter’s resistome, supporting the development of surveillance programs of antimicrobial resistance in Chile.

While the ability of Campylobacter to cause human disease is thought to be multifactorial, there are several genes associated with its virulence, which role in campylobacteriosis is not fully understood [58]. Genome analysis showed that clinical C. jejuni strains harbored most of the known virulence factors described for the species. On the contrary, C. coli strains lacked most virulence genes described for C. jejuni (Fig 5). Since most of our knowledge regarding the virulence of Campylobacter comes from studies performed in C. jejuni, this highlights the need for a better understanding of how C. coli strains cause disease. A limitation of our resistome and virulome analysis is that most of our data comes from draft whole genomes. Therefore, it is possible that the presence/absence of some loci may have been missed. Nevertheless, our dataset of 17 closed genomes allowed us to gain insight into the genomic context of the T4SS and T6SS gene clusters of C. jejuni.

To date, there is only one T6SS cluster described in Campylobacter [40]. This T6SS has been shown to contribute to host cell adherence, invasion, resistance to bile salts and oxidative stress [59–61], and required for the colonization of murine [59] and avian [61] infection models. We identified a complete T6SS gene cluster in 9 C. jejuni and in 1 C. coli strain (Fig 5). No correlation was found between presence of the T6SS and any particular ST, which differs from what has been described in Israel, where most T6SS-positive strains belong to ST-1359 [51]. Although ST-1359 was the most common ST described in this study, none of the strains carried a T6SS.

Two distinct T4SSs have been described in Campylobacter. One T4SS is encoded in the pVir plasmid of C. jejuni and has been shown to contribute to the invasion of INT407 cells and the ability to induce diarrhea in a ferret infection model [42,62]. The second T4SS is encoded in the pTet and pCC31 plasmids of C. jejuni and C. coli, which contributes to bacterial conjugation and is not directly linked to virulence [49]. Each of the T4SS gene clusters identified in our strains showed a high degree of identity to the pTet and pCC31 T4SSs. Suggesting that they do not directly contribute to virulence, but they might facilitate horizontal gene transfer events that could lead to increase fitness and virulence.

Altogether, we provide valuable epidemiological and genomic data of the diversity, virulence and resistance profiles of a large collection of clinical Campylobacter strains from Chile. Further studies are needed to determine the dynamics of transmission of pathogenic Campylobacter to humans and the potential emergence of new virulence and antimicrobial resistance markers in order to provide actionable public health data to support the design of strengthened surveillance programs in Chile and South America.

Supporting information

(TIF)

(A) T6SS gene clusters of C. jejuni and C. coli strains (bold) compared to the cluster of C. jejuni strain 108. Genes tagH, tssD, tssB and tssC are shown in color. (B) T4SS gene clusters of C. jejuni strains in comparison to the T4SS gene clusters of pTet and pCC31. The cp33 gene is highlighted in orange. BLASTn alignments were performed and visualized using EasyFig.

(TIF)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Cells with a red background represent presence. Empty cells represent absence of the gene in each genome.

(XLSX)

Data Availability

All draft genome sequence reannotations, sequence fasta files and outputs of the roary software are available as a supplementary dataset on Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3925206.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by fundings from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI)-Gulbenkian International Research Scholar Grant #55008749, FONDECYT Grant 1201805 (ANID) and REDI170269 (ANID) from CJB. VB is supported by DICYT grant 022001BZ (USACH). AK is supported by FONDECYT Grant 1191074 (ANID). NJG is supported by MCMi Challenge Grants program proposal number 2018-646 and the FDA Foods Program Intramural Funds (FDA employees). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Kaakoush NO, Castaño-Rodríguez N, Mitchell HM, et al. Global Epidemiology of Campylobacter Infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28:687–720. 10.1128/CMR.00006-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, World Organisation for Animal Health. The global view of campylobacteriosis: report of an expert consultation, Utrecht, Netherlands, 9–11 July 2012 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/80751. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Acheson D, Allos BM. Campylobacter jejuni Infections: Update on Emerging Issues and Trends. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2001;32:1201–1206. 10.1086/319760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization E. Global priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to guide research, discovery, and development of new antibiotics. 2017;7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernández H. Campylobacter and campylobacteriosis: a view from South America. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2011;28:121–127. 10.1590/s1726-46342011000100019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pascoe B, Schiaffino F, Murray S, et al. Genomic epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni associated with asymptomatic pediatric infection in the Peruvian Amazon. Makepeace BL, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14:e0008533. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Instituto de Salud Pública de Chile. Vigilancia de laboratorio de Campylobacter spp. Chile, 2005–2013. Boletín ISP. 2014;4:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Porte Lorena, Weitzel T, Barbe M, et al. Routine molecular diagnosis of enteropathogens by the FilmArray gastrointestinal panel in a microbiological laboratory in Santiago, Chile. 28th European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2018; [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collado L, Muñoz N, Porte L, et al. Genetic diversity and clonal characteristics of ciprofloxacin-resistant Campylobacter jejuni isolated from Chilean patients with gastroenteritis. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2018;58:290–293. 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rivera F N, Bustos B R, Montenegro H S, et al. Genotyping and antibacterial resistance of Campylobacter spp strains isolated in children and in free range poultry. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2011;28:555–562. doi: /S0716-10182011000700008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez-Hein G, Cordero N, García P, et al. Análisis molecular de la resistencia a fluoroquinolonas y macrólidos en aislados de Campylobacter jejuni de humanos, bovinos y carne de ave. Rev chil infectol. 2013;30:135–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lapierre L, Gatica MA, Riquelme V, et al. Characterization of Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Its Association with Virulence Genes Related to Adherence, Invasion, and Cytotoxicity in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli Isolates from Animals, Meat, and Humans. Microbial Drug Resistance. 2016;22:432–444. 10.1089/mdr.2015.0055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levican A, Ramos-Tapia I, Briceño I, et al. Genomic Analysis of Chilean Strains of Campylobacter jejuni from Human Faeces. BioMed Research International. 2019;2019:1–12. 10.1155/2019/1902732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bravo V, Varela C, Porte L, et al. Draft Whole-Genome Sequences of 51 Campylobacter jejuni and 12 Campylobacter coli Clinical Isolates from Chile. Rasko D, editor. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2020;9:MRA.00072-20, e00072–20. 10.1128/MRA.00072-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bravo V, Porte L, Weitzel T, et al. Complete genome sequences of 17 clinical Campylobacter jejuni strains from Chile. Microbiology Resource Announcements.: 9:e00535–20. 10.1128/MRA.00535-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darling AE, Mau B, Perna NT. progressiveMauve: Multiple Genome Alignment with Gene Gain, Loss and Rearrangement. Stajich JE, editor. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11147. 10.1371/journal.pone.0011147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jolley KA, Bray JE, Maiden MCJ. Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications. Wellcome Open Res. 2018;3:124. 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14826.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cody AJ, Bray JE, Jolley KA, et al. Core Genome Multilocus Sequence Typing Scheme for Stable, Comparative Analyses of Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli Human Disease Isolates. Diekema DJ, editor. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:2086–2097. 10.1128/JCM.00080-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jünemann S, Sedlazeck FJ, Prior K, et al. Updating benchtop sequencing performance comparison. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:294–296. 10.1038/nbt.2522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Research. 2019;47:W256–W259. 10.1093/nar/gkz239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, et al. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seemann T. tseemann/abricate [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 2]. Available from: https://github.com/tseemann/abricate.

- 25.Zankari E, Hasman H, Cosentino S, et al. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2012;67:2640–2644. 10.1093/jac/dks261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jia B, Raphenya AR, Alcock B, et al. CARD 2017: expansion and model-centric curation of the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D566–D573. 10.1093/nar/gkw1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta SK, Padmanabhan BR, Diene SM, et al. ARG-ANNOT, a New Bioinformatic Tool To Discover Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Bacterial Genomes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:212–220. 10.1128/AAC.01310-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feldgarden M, Brover V, Haft DH, et al. Validating the AMRFinder Tool and Resistance Gene Database by Using Antimicrobial Resistance Genotype-Phenotype Correlations in a Collection of Isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63:e00483–19, /aac/63/11/AAC.00483-19.atom. 10.1128/AAC.00483-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sullivan MJ, Petty NK, Beatson SA. Easyfig: a genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1009–1010. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Page AJ, Cummins CA, Hunt M, et al. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3691–3693. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roosaare M, Puustusmaa M, Möls M, et al. PlasmidSeeker: identification of known plasmids from bacterial whole genome sequencing reads. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4588. 10.7717/peerj.4588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stothard P, Grant JR, Van Domselaar G. Visualizing and comparing circular genomes using the CGView family of tools. Briefings in Bioinformatics. 2019;20:1576–1582. 10.1093/bib/bbx081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Méric G, Yahara K, Mageiros L, et al. A Reference Pan-Genome Approach to Comparative Bacterial Genomics: Identification of Novel Epidemiological Markers in Pathogenic Campylobacter. Bereswill S, editor. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e92798. 10.1371/journal.pone.0092798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luangtongkum T, Jeon B, Han J, et al. Antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter: emergence, transmission and persistence. Future Microbiology. 2009;4:189–200. 10.2217/17460913.4.2.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang Y, Fang L, Xu C, et al. Antibiotic resistance trends and mechanisms in the foodborne pathogen, Campylobacter. Anim Health Res Rev. 2017;18:87–98. 10.1017/S1466252317000135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Connell SR, Trieber CA, Dinos GP, et al. Mechanism of Tet(O)-mediated tetracycline resistance. EMBO J. 2003;22:945–953. 10.1093/emboj/cdg093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bolinger H, Kathariou S. The Current State of Macrolide Resistance in Campylobacter spp.: Trends and Impacts of Resistance Mechanisms. Schaffner DW, editor. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017;83:e00416–17, e00416-17. 10.1128/AEM.00416-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alfredson DA, Korolik V. Isolation and expression of a novel molecular class D beta-lactamase, OXA-61, from Campylobacter jejuni. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2515–2518. 10.1128/AAC.49.6.2515-2518.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu B, Zheng D, Jin Q, et al. VFDB 2019: a comparative pathogenomic platform with an interactive web interface. Nucleic Acids Research. 2019;47:D687–D692. 10.1093/nar/gky1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Redondo N, Carroll A, McNamara E. Molecular characterization of Campylobacter causing human clinical infection using whole-genome sequencing: Virulence, antimicrobial resistance and phylogeny in Ireland. Zilch TJ, editor. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0219088. 10.1371/journal.pone.0219088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agnetti J, Seth-Smith HMB, Ursich S, et al. Clinical impact of the type VI secretion system on virulence of Campylobacter species during infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:237. 10.1186/s12879-019-3858-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bacon DJ, Alm RA, Burr DH, et al. Involvement of a Plasmid in Virulence of Campylobacter jejuni 81–176. Barbieri JT, editor. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4384–4390. 10.1128/iai.68.8.4384-4390.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dasti JI, Tareen AM, Lugert R, et al. Campylobacter jejuni: A brief overview on pathogenicity-associated factors and disease-mediating mechanisms. International Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2010;300:205–211. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2009.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Konkel ME, Kim BJ, Rivera-Amill V, et al. Bacterial secreted proteins are required for the internaliztion of Campylobacter jejuni into cultured mammalian cells. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:691–701. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01376.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Novik V, Hofreuter D, Galán JE. Identification of Campylobacter jejuni genes involved in its interaction with epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2010;78:3540–3553. 10.1128/IAI.00109-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ghorbanalizadgan M, Bakhshi B, Kazemnejad Lili A, et al. A molecular survey of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli virulence and diversity. Iran Biomed J. 2014;18:158–164. 10.6091/ibj.1359.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghatak S, He Y, Reed S, et al. Whole genome sequencing and analysis of Campylobacter coli YH502 from retail chicken reveals a plasmid-borne type VI secretion system. Genom Data. 2017;11:128–131. 10.1016/j.gdata.2017.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taveirne ME, Dunham DT, Perault A, et al. Complete Annotated Genome Sequences of Three Campylobacter jejuni Strains Isolated from Naturally Colonized Farm-Raised Chickens. Genome Announc. 2017;5:e01407–16, e01407-16. 10.1128/genomeA.01407-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Batchelor RA, Pearson BM, Friis LM, et al. Nucleotide sequences and comparison of two large conjugative plasmids from different Campylobacter species. Microbiology (Reading, Engl). 2004;150:3507–3517. 10.1099/mic.0.27112-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Collado L. Diagnóstico microbiológico y vigilancia epidemiológica de la campilobacteriosis en Chile: Situación actual y desafíos futuros. Rev chil infectol. 2020;37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rokney A, Valinsky L, Moran-Gilad J, et al. Genomic Epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni Transmission in Israel. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2432. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sheppard SK, Maiden MCJ. The Evolution of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015;7:a018119. 10.1101/cshperspect.a018119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frazão MR, Cao G, Medeiros MIC, et al. Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles and Phylogenetic Analysis of Campylobacter jejuni Strains Isolated in Brazil by Whole Genome Sequencing. Microbial Drug Resistance. 2020;mdr.2020.0184. 10.1089/mdr.2020.0184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cody AJ, McCarthy NM, Wimalarathna HL, et al. A Longitudinal 6-Year Study of the Molecular Epidemiology of Clinical Campylobacter Isolates in Oxfordshire, United Kingdom. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2012;50:3193–3201. 10.1128/JCM.01086-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fernández H, Pérez-Pérez G. Campylobacter: fluoroquinolone resistance in Latin-American countries. Archivos de medicina veterinaria. 2016;48:255–259. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Van Boeckel TP, Brower C, Gilbert M, et al. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:5649–5654. 10.1073/pnas.1503141112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maron D, Smith TJ, Nachman KE. Restrictions on antimicrobial use in food animal production: an international regulatory and economic survey. Global Health. 2013;9:48. 10.1186/1744-8603-9-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hansson I, Sandberg M, Habib I, et al. Knowledge gaps in control of Campylobacter for prevention of campylobacteriosis. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2018;65:30–48. 10.1111/tbed.12870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lertpiriyapong K, Gamazon ER, Feng Y, et al. Campylobacter jejuni Type VI Secretion System: Roles in Adaptation to Deoxycholic Acid, Host Cell Adherence, Invasion, and In Vivo Colonization. Bereswill S, editor. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42842. 10.1371/journal.pone.0042842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bleumink-Pluym NMC, van Alphen LB, Bouwman LI, et al. Identification of a Functional Type VI Secretion System in Campylobacter jejuni Conferring Capsule Polysaccharide Sensitive Cytotoxicity. Gaynor EC, editor. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003393. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liaw J, Hong G, Davies C, et al. The Campylobacter jejuni Type VI Secretion System Enhances the Oxidative Stress Response and Host Colonization. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2864. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bacon DJ, Alm RA, Hu L, et al. DNA sequence and mutational analyses of the pVir plasmid of Campylobacter jejuni 81–176. Infect Immun. 2002;70:6242–6250. 10.1128/iai.70.11.6242-6250.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(TIF)

(A) T6SS gene clusters of C. jejuni and C. coli strains (bold) compared to the cluster of C. jejuni strain 108. Genes tagH, tssD, tssB and tssC are shown in color. (B) T4SS gene clusters of C. jejuni strains in comparison to the T4SS gene clusters of pTet and pCC31. The cp33 gene is highlighted in orange. BLASTn alignments were performed and visualized using EasyFig.

(TIF)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Cells with a red background represent presence. Empty cells represent absence of the gene in each genome.

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All draft genome sequence reannotations, sequence fasta files and outputs of the roary software are available as a supplementary dataset on Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3925206.