Abstract

Background

Dexamethasone and remdesivir have the potential to reduce coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID)–related mortality or recovery time, but their cost-effectiveness in countries with limited intensive care resources is unknown.

Methods

We projected intensive care unit (ICU) needs and capacity from August 2020 to January 2021 using the South African National COVID-19 Epi Model. We assessed the cost-effectiveness of (1) administration of dexamethasone to ventilated patients and remdesivir to nonventilated patients, (2) dexamethasone alone to both nonventilated and ventilated patients, (3) remdesivir to nonventilated patients only, and (4) dexamethasone to ventilated patients only, all relative to a scenario of standard care. We estimated costs from the health care system perspective in 2020 US dollars, deaths averted, and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios of each scenario.

Results

Remdesivir for nonventilated patients and dexamethasone for ventilated patients was estimated to result in 408 (uncertainty range, 229–1891) deaths averted (assuming no efficacy [uncertainty range, 0%–70%] of remdesivir) compared with standard care and to save $15 million. This result was driven by the efficacy of dexamethasone and the reduction of ICU-time required for patients treated with remdesivir. The scenario of dexamethasone alone for nonventilated and ventilated patients requires an additional $159 000 and averts 689 [uncertainty range, 330–1118] deaths, resulting in $231 per death averted, relative to standard care.

Conclusions

The use of remdesivir for nonventilated patients and dexamethasone for ventilated patients is likely to be cost-saving compared with standard care by reducing ICU days. Further efforts to improve recovery time with remdesivir and dexamethasone in ICUs could save lives and costs in South Africa.

Keywords: cost-effectiveness, COVID-19, dexamethasone, hospital bed capacity, intensive care, mathematical model, remdesivir, SARS-CoV-2

As of September 2020, there were over 29 million confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections worldwide and over 939 000 reported coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)–associated deaths [1]. South Africa has the eighth highest number of confirmed cases worldwide, with more than 653 000 confirmed infections and 16 000 confirmed COVID-19 deaths [2]. During the surge in cases, intensive care unit (ICU) capacity was reportedly breached in some locations and much-needed oxygen supplies were running low [3]. While increased mortality is associated with several individual-level factors including older age, male sex, and preexisting comorbidities, systems-level factors such as being admitted to a hospital with fewer ICU beds also play a role [4]. Considering interhospital variation in treatment and outcomes, the mortality rate among those in ICUs has ranged between 40% and 50% [4–6]. To mitigate the mortality impact of COVID-19 in South Africa and other low- and middle-income countries with scant intensive care capacity, efforts to reduce mortality and duration of hospital stay among the more severe cases in ICUs are paramount. Recently, 2 therapeutic agents, remdesivir and dexamethasone, have been demonstrated in randomized clinical trials to reduce COVID-related mortality and recovery time in ICUs [7, 8].

Dexamethasone has been shown to decrease mortality by 35% (95% CI, 18%–49%) and 20% (95% CI, 8%–30%) in ventilated ICU patients and nonventilated patients with oxygen, respectively, and there has been no clear evidence regarding its impact on recovery time [7], while remdesivir has been shown to reduce recovery time from 15 (95% CI, 13–18) to 10 (95% CI, 9–11) days among ICU patients who are not ventilated [8] with no clear evidence regarding its impact on mortality [9, 10]. In low- and middle- income countries, not only is ICU capacity limited, but so are budgets for COVID-related care. There has been an additional budget allocation of $1.14 billion for the health response to COVID-19 in South Africa [11], though this budget does not yet include remdesivir or dexamethasone. We therefore conducted a cost-effectiveness analysis to determine the incremental cost per death averted of providing dexamethasone and remdesivir relative to the standard care of critically ill patients in South African ICUs from a health systems perspective. The cost-effectiveness of these regimens is going to become increasingly important for the eventuality of a COVID-19 resurgence in South Africa. Additionally, given the recent uncertainty about the clinical benefit of remdesivir, this analysis can further serve as a proxy for any intervention or treatment that reduces overall mortality, initiation of ventilation, and duration of hospital stay to determine cost-effectiveness up front.

METHODS

In South Africa, there were a reported 3318 public (1178) and private (2140) ICU beds available in total [12], and it was reported that only 70% (2309 beds) were available for COVID patients as of May 31, 2020 [13]. Using the South African National COVID-19 Epidemiology Model (NCEM) [14] and government data on the number of currently available ICU beds in the public and private sectors by province [12], we projected the number of people requiring ICU admission and total ICU person days by province by month between August 2020 and January 2021 (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). We then projected costs and COVID-related mortality for 4 scenarios: (1) remdesivir administered to nonventilated patients (ie, those receiving supplemental oxygen in an earlier stage of disease illness) and dexamethasone administered to ventilated patients (ie, in an advanced stage of disease illness), (2) dexamethasone alone administered to both nonventilated and ventilated patients, (3) remdesivir administered to nonventilated patients only, and (4) dexamethasone administered to ventilated patients only, all relative to standard of ICU care (without remdesivir and dexamethasone).

Our effectiveness measure was expressed as COVID-19 deaths averted. The mortality impact for all patients in ICUs between August 2020 and January 2021 was estimated by applying the treatment impact of remdesivir and dexamethasone on mortality from the results of recent randomized controlled trials [7–9], and impact on mortality that remdesivir could have was estimated through decreasing the average length of stay of patients (from 15 to 10 days) [8], when ICU capacity is expected to be breached (such that fewer people would die waiting for an ICU bed when those in the ICU are treated with remdesivir). Based on South African COVID-19 hospitalization data and treatment guidelines [15], we assumed that 42% of patients in the ICU require mechanical ventilation, while the remaining (58%) patients do not yet require mechanical ventilation (though they might require supplementary oxygen). A course of dexamethasone (oral/intravenous administration) is assumed to be 10 days long, and a course of remdesivir (intravenous) is assumed to be 5 days long (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison Between Remdesivir and Dexamethasone as COVID-19 Treatment in South Africa

| Remdesivir | Dexamethasone | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Regimen [12] | Antiviral: 200-mg IV loading dose followed by 100 mg IV daily for up to 5 days for patients who are hospitalized | Steroid: 6 mg PO/IV for up to 10 days for patients with an oxygen requirement and/or requiring mechanical ventilation | |

| Clinical trial [8, 12, 15] | WHO Solidarity Trial; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Clinical Trial | Oxford RECOVERY trial | |

| Clinical outcome [8, 12, 15] | Median time to recovery | From 10 (9–11) days in standard care to 15 (13–18) days with remdesivir | N/A |

| Overall | RR, 0.95 (HR, 0.81–1.11) | RR, 0.83 (95% CI, 0.74−0.92) | |

| Patients receiving high-flow oxygen or noninvasive mechanical ventilation | RR, 0.86 (HR, 0.67–1.11)a | RR, 0.80 (95% CI, 0.70–0.92)a | |

| Patients receiving mechanical ventilation | RR, 1.20 (HR, 0.80–1.80) | RR, 0.65 (95% CI, 0.51–0.82)a | |

| Availability [16, 17] | Possibly in short supply | Currently in market | |

| Any adverse events [18, 19] | Remdesivir vs placebo: 66% vs 64% for any group, 8% vs 14% for patients receiving oxygen | N/A |

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; HR, hazard ratio; IV, intravenous; NIAID, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; PO, oral; RR, relative risk; WHO, World Health Organization.

aMortality reduction rates used for remdesivir and dexamethasone in the model.

We estimated resource use from the perspective of the provider, the South African health care system, for all ICU days accrued by COVID-19 patients from August 2020 and January 2021 for each scenario. Note that since COVID-19 patients will be accommodated in both the private and public sector, depending on need and availability, and contracting arrangements toward that end were in place in all provinces at the time of writing, we combined both sectors for the purpose of this analysis. We calculated health system operational cost (excluding drug costs) based on the latest NCEM outputs (ie, required total ICU beds and days) with and without remdesivir and/or dexamethasone. We used an ICU cost per person day of $1128 ($665–$1172) based on an ingredients-based costing analysis including capital equipment, current South African ICU staffing norms and salaries, and overhead costs representative of South Africa public hospital settings (Edoka et al., Unpublished data). Capital assets (eg, ventilators) were annualized based on the relevant years of useful life (eg, 10 years) and discounted at a 5% annual rate based on the South Africa pharmacoeconomic guidelines [20].

For the scenarios including novel therapeutics, we assumed the additional cost of a full course of remdesivir ($55 per 100 mg IV, corresponding to $330 per patient course) [21] and/or dexamethasone ($3.13 per 4 mg, corresponding to $31 per patient course) [22] for the respective scenarios that include these therapeutics (Table 2). Costs were converted from South African Rands (ZAR) to US dollars (USD) at the average exchange rate over the period August 2020 to January 2021 (1 USD = 16.95 ZAR) [23]. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios were calculated as the incremental cost in 2020 USD of each therapeutic scenario over standard care per death averted.

Table 2.

Key Input Parameters

| Patient Disease Status in ICU | Base | Low | High | Distribution | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of patients requiring mechanical ventilation | 42 | 34 | 49 | Triangular | [8, 12, 13, 15] |

| Days of hospitalization for nonventilated patients | 15 | 5 | 18 | Triangular | |

| Days of hospitalization for ventilated patients | 19 | 13 | 32 | Triangular | |

| Efficacy | Base | Low | High | Distribution | Source |

| Reduced days of hospitalization with remdesivir (from 15 days to 10 days) | 5 | 1 | 9 | Triangular | [14, 15] |

| Mortality if those additional patients receive ICU care, % | 50 | 40 | 85 | Beta | [12] |

| Mortality if those additional patients do not receive ICU care, % | 90 | 85 | 100 | Beta | [12] |

| Mortality rate reduction for earlier stage (nonventilated) patients due to remdesivir, % | 0 | 0 | 70 | Beta | [14, 15] |

| Mortality rate reduction for later stage (ventilated) patients due to dexamethasone, % | 35 | 18 | 49 | Beta | [8] |

| Mortality rate reduction for earlier stage (nonventilated) patients due to dexamethasone, % | 20 | 8 | 30 | Beta | [8] |

| Cost inputs | USD | Low | High | Distribution | Source |

| Health system operation cost in ICU per person day, $ | 1128 | 665 | 1172 | Gamma | [15] |

| Cost of remdesivir regimen (200-mg IV loading dose followed by 100 mg IV daily for a maximum of 5 days), $ | 330 | 99 | 400 | Gamma | [17] |

| Cost of dexamethasone regimen (6 mg PO/IV for up to 10 days), $ | 31 | 16 | 47 | Gamma | [18] |

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ICU, intensive care unit; IV, intravenous; PO, oral.

We performed 1-way and 3-way sensitivity analyses on all model parameters to describe the robustness of the primary results, expressed as incremental cost per death averted, to uncertainty in individual model parameters. Parameters for the 3-way sensitivity analysis were selected as the most influential parameters in 1-way sensitivity analysis. Under our baseline assumptions, we also investigated whether and to what extent the benefit of a reduction in the length of ICU stay with remdesivir may differ by assuming (1) capacity being breached for all months in all provinces vs (2) capacity never being breached. To explore the combined effect of uncertainty in our model parameters, we conducted a probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA). All model parameter values were randomly sampled over prespecified distributions (Table 2), and 1000 simulations were performed to produce cost-effectiveness acceptability curves. The model was constructed in Microsoft Excel using an Excel Visual Basic Macro to run the simulations.

RESULTS

The estimated total health systems operation cost of COVID-19-related ICU care in South Africa excluding drugs during August 2020 to January 2021 was $83.9 million without remdesivir (standard care) and $68.3 million with remdesivir due to the reduction in required total ICU person days. In terms of drug costs, we estimated $995 000 required for remdesivir administered to nonventilated patients, $67 000 for dexamethasone administered to ventilated patients, or $159 000 when dexamethasone is administered to all patients in the ICU across all 6 months (Supplementary Table 3).

Overall, the scenario with a combination of remdesivir and dexamethasone could save $14.6 million relative to standard care and avert a total of 408 deaths (Table 3). Of these, 26 deaths would be averted due to remdesivir (by decreasing the average length of stay of patients when ICU capacity is expected to be breached), and 382 deaths would be averted due to the direct effect of dexamethasone on mortality. Similarly, the scenario of only administering remdesivir to nonventilated patients could save $14.7 million relative to standard care due to a reduction in ICU days, but would result in fewer total deaths averted (26) when assuming 0% reduction in mortality. The scenario with dexamethasone alone administered to ventilated and nonventilated patients requires additional $159 000 but averts 689 deaths ($231 per death averted) relative to standard care. Therefore, as remdesivir becomes available and should it reduce recovery time in the ICU, the use of remdesivir in combination with dexamethasone is recommended given the substantial cost savings and similar health benefit.

Table 3.

Total Costs, Health Outcome, and Incremental Cost-effectiveness Ratios of COVID-19 Treatment Scenarios in South Africa From August 2020 to January 2021 (With 95% Uncertainty Ranges Reported as the 2.5th and 97.5th Percentiles of the Corresponding Distributions)

| Deaths Averteda | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenarios | Total Costs, in Thousands USD | Incremental Cost, in Thousands USD (Ref: Standard Care) | Remdesivir | Dexamethasone | Total | Cost per Death Averted | |

| Reference: standard care | 83 937 (43 612 to 104 632) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |

| 1 | Remdesivir for nonventilated patients & dexamethasone for ventilated patients | 69 346 (41 327 to 99 623) | Cost savings: –14 591 (–59 027 to 29 878) | 26 (21 to 1497) | 382 (140 to 679) | 408 (229 to 1891) | Cost saving |

| 2 | Dexamethasone for nonventilated & ventilated patients | 84 096 (53 093 to 119 164) | Cost increase: 159 (61 to 307) | n/a | 689 (330 to 1118) | 689 (330 to 1118) | 231 (80 to 647) |

| 3 | Remdesivir for nonventilated patients (58%) only | 69 279 (41 301 to 99 492) | Cost savings: –14 657 (–59 087 to 29 778) | 26 (21 to 1497) | n/a | 26 (21 to 1497) | Cost saving |

| 4 | Dexamethasone for ventilated patients (42%) only | 84 003 (53 058 to 118 988) | Cost increase: 67 (26 to 130) | n/a | 382 (140 to 679) | 382 (140 to 679) | 174 (59 to 555) |

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ICU, intensive care unit.

aEach scenario is compared with standard care. The number represents death averted by remdesivir assuming 0% reduction in mortality. If we assume 30% reduction in mortality of remdesivir, the total number of deaths averted by scenario 1 (dexamethasone for ventilated patients & remdesivir for nonventilated patients) would be 882 (averting 382 deaths by dexamethasone and 500 deaths by remdesivir due to decreasing the average length of stay of patients when ICU capacity is expected to be breached (474) and drug efficacy (26). Accordingly, the total number of deaths averted by scenario 4 (remdesivir for nonventilated patients; 58%) would only be 500.

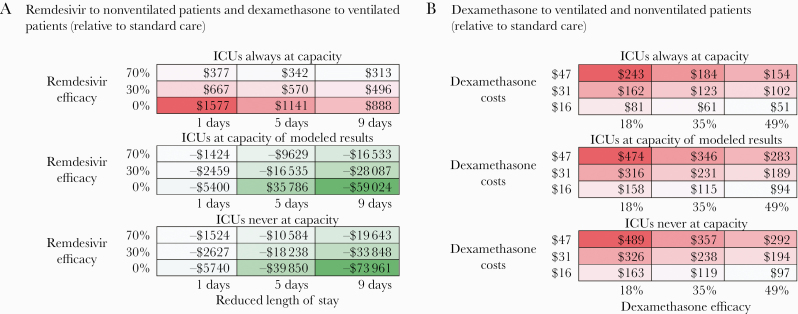

Our 1-way sensitivity analysis reveals that the uncertainty in the length of stay reduction from remdesivir, number of months ICU capacity is breached, and efficacy of remdesivir and dexamethasone have the greatest impact on the ICER (Figure 1). The 3-way sensitivity analysis (Figure 2A) reveals that, assuming 0% remdesivir efficacy, if the ICU capacity is not expected to be breached at all, then the remdesivir and dexamethasone combination scenario could save up to $15 million (mainly due to the reduced total ICU days and health systems costs from remdesivir) and avert 383 deaths relative to standard care. But if ICU capacity is expected to be breached in all months and in all provinces, a scenario that includes the combination of remdesivir and dexamethasone would result in an additional drug cost of $12 million but avert 10 394 deaths (5773 from excess death and 4621 from dexamethasone efficacy), resulting in $1141 per death averted relative to standard care. Even if remdesivir reduces mortality by 0% and only has a 1-day reduction in hospital stay, the scenario of remdesivir and dexamethasone combination would avert between 383 deaths, with a $2 million cost savings, and 5446 deaths, with a $8.6 million cost increase ($1577 per death averted) from 0 to 6 months across all provinces of ICU capacity being breached, respectively.

Figure 1.

One-way sensitivity analyses of incremental cost-effectiveness ratio assessing the use of remdesivir for nonventilated intensive care unit patients and dexamethasone for ventilated patients compared with standard care (assuming 0% efficacy of remdesivir in directly reducing mortality). Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

Figure 2.

Three-way sensitivity analyses of incremental cost-effectiveness ratio assessing the use of remdesivir for nonventilated intensive care unit (ICU) patients and dexamethasone for ventilated patients compared with standard care. This heat map displays the incremental cost-effectiveness (red as an incremental cost per death averted; green as an incremental cost saving per death averted) of the scenario of remdesivir and dexamethasone compared with standard care (A) and the scenario of dexamethasone use in ventilated and nonventilated patients compared with standard care (B). Each panel corresponds to a relative epidemic condition (the extent of ICU capacity is breached across 6 months/9 provinces: full [ICUs always at capacity], base [ICUs at capacity as per modeled results], low [ICUs never at capacity]). In (A), each column represents a different length of reduced ICU stay by remdesivir and each row depicts a different remdesivir efficacy (0%, 30%, 70%). In (B), each column represents a different dexamethasone efficacy (18%, 35%, 49%), and each row depicts a different dexamethasone cost ($16, $31, $47).

The results of the PSA, displayed in cost-effectiveness acceptability curves, show the probability of the intervention being cost-effective under different willingness-to-pay thresholds. We used the threshold value of $3015 per DALY averted in South Africa [24], which can be translated to $36 000 per death averted, assuming the average discounted life expectancy at time of COVID death in South Africa to be 17 years (12 DALYs per death). Our findings show substantial cost savings for the intervention that included remdesivir and a cost of <$300 per death averted (uncertainty range, $80–$647 per death averted) for the intervention of dexamethasone (Table 3); these values fall far below any plausible threshold. For example, at an a priori willingness-to-pay threshold of $1000 per death averted, it is highly likely that the use of dexamethasone alone (to both nonventilated and ventilated patients or ventilated patients only) will be cost-effective (as shown, almost 100% of simulation estimates fell below the threshold) compared with standard care in South Africa (Supplementary Figure 1). The scenarios that include remdesivir show that almost 75% of simulations fall below the cost-saving threshold (ie, incremental cost is <$0) with more variability, mainly due to the uncertainty around the reduced length of ICU stay, which is associated with high hospital costs per day.

DISCUSSION

This analysis explores whether and to what extent remdesivir and dexamethasone might be considered cost-effective for critically ill COVID-19 patients in South Africa. We find that treating nonventilated and ventilated patients with dexamethasone is expected to maximize the number of deaths averted (689) at an incremental cost of $159 000, but treating nonventilated patients with remdesivir and ventilated patients with dexamethasone could avert 408 deaths, with substantial cost savings of $15 million relative to standard care between August 2020 and January 2021 by reducing ICU days for the estimated COVID-19 patients being admitted to the ICU. This cost savings would offset all of the remdesivir- and dexamethasone-related costs, and the scenario including remdesivir would also help to alleviate already highly constrained ICU capacity. Despite great uncertainty in both efficacy and length of stay reduction for remdesivir [8–10], our results could be applied to any drug or intervention that reduces the duration of ICU stay. An intervention or drug that costs the same or less than the cost per ICU day (ie, 3 times the current remdesivir cost, $330) and reduces ICU stay just by 1 day could likely achieve cost neutrality.

These results extend earlier findings regarding the mortality impact of remdesivir alone by reducing length of ICU stay and treating more COVID-19 patients in the ICU [14] using the months of the first peak (June–August 2020) of the COVID-19 epidemic in South Africa, when resources were severely constrained. The number of deaths averted due to increasing ICU capacity in this analysis differs from our previous findings [14]. This is due to 2 factors. First, in this analysis we are assuming that only some patients in the ICU receive remdesivir, instead of all patients. Second, the most recent set of model predictions from the NCEM project a waning epidemic in which ICU capacity is seldom breached. This has resulted in many fewer deaths averted than projected due to increasing ICU capacity.

The cost savings of remdesivir are mainly driven by the reduced length of ICU stay, which is associated with high hospital costs per day. The cost savings, however, are also strongly influenced by the level and speed of epidemic control, varying from $15 million cost savings to a $12 million cost increase from 0 to 6 months across all provinces of ICU capacity being breached, respectively. The $12 million increase in cost is expected in a fully breached scenario given that all available COVID-related ICU days will be utilized during the full time period. Though a cost increase would be expected in this scenario, there would be a reduction in mortality by increasing the number of people who can be treated in the ICU through a reduction in length of stay facilitated by remdesivir [13]. If ICU capacity is only breached in the first month (August) in the 9 provinces and there is no breach at all in the subsequent months, the scenario of remdesivir and dexamethasone combined would result in a $4 million cost savings. If ICU capacity is, however, breached during the first 2 months (from August to September) in all 9 provinces and there is no breach at all in the subsequent months, the scenario of remdesivir and dexamethasone combined would cost an additional $2 million relative to standard care. Therefore, the duration of the breach directly corresponds to the level of cost savings or expenditure that may be expected from the use of remdesivir and dexamethasone during a declining COVID-19 pandemic.

On the other hand, the cost-effectiveness of dexamethasone is mainly determined by the relationship between the drug cost and efficacy. As the drug cost is relatively low ($31), particularly as compared with the cost of remdesivir ($330) or hospital stay cost ($1128), the ICU-specific parameters (ie, cost per ICU stay, mortality rate of those in the ICU) were instead greater influencers of the ICER for the scenario of dexamethasone for ventilated and nonventilated patients. Dexamethasone has a greater impact, however, on averting deaths (efficacy of 35% when administered to ventilated patients and 20% when administered to nonventilated patients). If more severe patients enter the ICU, the cost-effectiveness of the dexamethasone scenario will continue to increase. Additionally, in the future, should dexamethasone also be shown to reduce the number of ICU days required, it will also likely be considered cost-saving, as with many of our estimates for remdesivir.

Our analysis has several limitations. First, the number of months that ICU capacity is breached is influenced by the interplay between epidemic conditions and policy choices (which can affect ICU admission of patients with other diseases) [25]. As this will have different implications for costs and health outcomes in each scenario, it will be important to consider regional heterogeneity in epidemic conditions, health system capacity, and willingness to pay in order to guide optimal treatment strategies and in order to generalize our results. Second, we did not consider potential changes in the clinical course with disease progression or changes of distribution of disease severity among the patient population over time. Importantly, the efficacy of remdesivir and dexamethasone in preventing mortality may be influenced by several factors—time of treatment initiation after symptom onset [26, 27], age [28], comorbidities [29], potential adverse events [18], and use of other medications [30, 31]. As additional treatment options become available [32], it would also be important to collect more data on the duration of illness and its relationship to the outcome (both in terms of efficacy and safety) [18] and conduct more detailed analyses considering patient population characteristics, change of epidemic curves, and local health system capacity, which can guide optimal treatment strategy in a resource-constrained setting. Third, our cost data do not include additional costs associated with adverse events management and also may not fully incorporate potential economies of scale due to increased volume of patients within a given ICU capacity. While the benefit of remdesivir in reduced length of ICU stay may not be limited to the ICU setting (and may thus decrease overall societal costs), we did not include this implication into the cost analysis as it is beyond our analytic scope. We used a single unit cost for ICU patient days based on a public sector costing analysis and did not differentiate costs or financial implications between public and private hospitals. While this may change the point estimate of our results, it is unlikely to alter our conclusions and would only result in greater cost savings/cost-effectiveness of the interventions. Continued efforts to develop clinical practice guidelines (ie, who to treat, where, how, and when) [33] to reduce length of ICU stay for patients in ICUs with COVID-19 [34, 35] could further improve clinical benefits and cost-effectiveness. Finally, given that the cost savings observed with remdesivir are driven by months when ICU capacity is not breached, the monetary value of remdesivir may increase during the next phase of the pandemic as new cases decline and the pressure on ICUs eases. Given great uncertainty in making long-term projections into 2021, the time horizon for this study was limited to the latest projections from the NCEM.

CONCLUSIONS

To conclude, our results show that treating nonventilated and ventilated patients with dexamethasone is expected to maximize the number of deaths averted, but treatment including remdesivir can be easily considered cost-saving under a wide range of uncertainty through the reduction of ICU days for COVID-19 patients being admitted to the ICU. Despite great uncertainty in both efficacy and length-of-stay reduction for remdesivir, our results suggest that any intervention or drug that costs the same or less than the cost per ICU day and reduces ICU stay just by 1 day could likely achieve cost neutrality. Cost savings are also strongly influenced by the level and speed of epidemic control to avoid ICU capacity being breached during a declining COVID-19 pandemic from the peak months. This analysis strongly supports treatment of COVID-19 patients in the ICU with dexamethasone and, should remdesivir improve recovery time, the treatment of early-stage ICU patients with remdesivir.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Financial support. This work was supported by the United States Agency for International Development (72067419CA00004). Youngji Jo is supported by the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award, National Institutes of Health T32 Training Grant (grant number: T32 AI052074-14). Lawrence Long was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) of the National Institutes of Health (grant number: 1K01MH119923-01A1). Ijeoma Edoka is supported by the South African Medical Research Council (grant number: 23108).

Disclaimer. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, the US Government, or the National Institutes of Health.

Potential conflicts of interest. B.N., I.S., and L.L. report grants from USAID during the conduct of the study. S.S. reports grants from the Wellcome Trust during the conduct of the study. L.L. reports grants from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation during the conduct of the study. The other authors have nothing to disclose. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Patient consent. Neither ethical approval nor informed consent was required for this analysis, which did not involve human subjects research.

References

- 1. Roser M, Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, Hasell J. Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). 2020. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus. Accessed 6 June 2020.

- 2.Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). COVID-19 dashboard. Available at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed 20 July 2020.

- 3. Magome M. Oxygen already runs low as COVID-19 surges in South Africa. The Washington Post. 10 July 2020. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/africa/oxygen-already-runs-low-as-covid-19-surges-in-south-africa/2020/07/10/c9b1bb5e-c293-11ea-8908-68a2b9eae9e0_story.html. Accessed 10 July 2020.

- 4. Kim L, Garg S, O’Halloran A, et al. Risk factors for intensive care unit admission and in-hospital mortality among hospitalized adults identified through the U.S. coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-associated hospitalization surveillance network (COVID-NET) [published online ahead of print July 16, 2020]. Clin Infect Dis 2020. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gupta S, Hayek SS, Wang W, et al. Factors associated with death in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in the US. JAMA Intern Med 2020; 180:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Armstrong RA, Kane AD, Cook TM. Outcomes from intensive care in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Anaesthesia 2020; 75:1340–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Group RC, Horby P, Lim WS, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19—preliminary report [published online ahead of print July 17, 2020]. N Engl J Med 2020. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19—final report. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:1813–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pan H, Peto R, Karim QA, et al. WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium . Repurposed antiviral drugs for Covid-19—Interim WHO Solidarity Trial results. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:497–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Spinner CD, Gottlieb RL, Criner GJ, et al. ; GS-US-540-5774 Investigators . Effect of remdesivir vs standard care on clinical status at 11 days in patients with moderate COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020; 324:1048–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ramaphosa C. Statement by President Cyril Ramaphosa on South Africa’s response to the coronavirus pandemic, Union Buildings, Tshwane. 23 April 2020. Available at: http://www.presidency.gov.za/speeches/statement-president-cyril-ramaphosa-south-africa%27s-response-coronavirus-pandemic%2C-union-buildings%2C-tshwane. Accessed 10 July 2020.

- 12. MASHA, HE2RO, SACEMA. Estimating cases for COVID-19 in South Africa: Long-Term National Projections. Pretoria, South Africa: National Institute of Communicable Diseases; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Basson A. Coronavirus: SA needs many more ICU beds to be ready for Covid-19 peaks, says Ramaphosa. news24. 31 May 2020. Available at: https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/news/coronavirus-sa-needs-many-more-icu-beds-to-be-ready-for-covid-19-peaks-says-ramaphosa-20200531. Accessed 30 July 2020.

- 14. Nichols BE, Jamieson L, Zhang SRC, et al. The role of remdesivir in South Africa: preventing COVID-19 deaths through increasing ICU capacity [published online ahead of print July 6, 2020]. Clin Infect Dis 2020. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Institute for Communicable Disease. COVID-19 guidelines. Available at: https://www.nicd.ac.za/diseases-a-z-index/covid-19/covid-19-guidelines/. Accessed 10 July 2020.

- 16. Diario AS. Remdesivir to be available in South Africa by the end of July. 8 July 2020. Available at: https://en.as.com/en/2020/07/08/latest_news/1594223072_744566.html. Accessed 10 July 2020.

- 17. Anadolu Agency. South Africa approves dexamethasone to treat COVID-19. 20 June 2020. Available at: https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/south-africa-approves-dexamethasone-to-treat-covid-19/1883532. Accessed 10 July 2020.

- 18. Davies M, Osborne V, Lane S, et al. Remdesivir in treatment of COVID-19: a systematic benefit-risk assessment. Drug Saf 2020; 43:645–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang Y, Zhang D, Du G, et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet 2020; 395:1569–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Department of Health. Medicines and Related Substances Act (101/1965) Regulations Relating to a Transparent Pricing System for Medicines and Scheduled Substances: Publication of Guidelines for Pharmacoeconomic Submissions. Pretoria, South Africa: Government Gazette; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Business Insider South Africa. The US is buying Covid-19 drug remdesivir like crazy. A generic is coming to SA – cheap. 3 July 2020. Available at: https://www.businessinsider.co.za/the-us-is-buying-covid-19-drug-remdesivir-like-crazy-a-generic-is-coming-to-sa-cheap-2020–7. Accessed 19 July 2020.

- 22. OpenData South Africa. Essential medicine and master procurement catalogue. Available at: https://odza.herokuapp.com/opendataza/resource/34. Accessed 19 July 2020.

- 23. Oanda. Oanda currency converter. 2020. Available at: www.oanda.com. Accessed 20 July 2020.

- 24. Edoka IP, Stacey NK. Estimating a cost-effectiveness threshold for health care decision-making in South Africa. Health Policy Plan 2020; 35:546–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Acemoglu D, Chernozhukov V, Werning I, Whinston M. Optimal targeted lockdowns in a multi-group SIR model. NBER Working Paper No. 27102. May 2020. Revised June 2020. Available at: https://www.nber.org/papers/w27102. Accessed 10 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gillenwater S, Rahaghi F, Hadeh A. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19—preliminary report. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:992–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McMahon JH, Udy A, Peleg AY. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19—preliminary report. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:992–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8:475–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA 2020; 323:2052–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Olalla J. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19—preliminary report. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:992–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sun D. Correction to: remdesivir for treatment of COVID-19: combination of pulmonary and IV administration may offer additional benefit. AAPS J 2020; 22:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Corum J, Wu KJ, Zimmer C. Coronavirus drug and treatment tracker. The New York Times. Updated 2 February 2021. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/science/coronavirus-drugs-treatments.html?fbclid=IwAR0L0oSIhEp8u0mAQiOfc3FRxCYHrBLm23kuq_M80yhVjWTonwn8m2wbsog. Accessed 17 July 2020.

- 33. National Institutes of Health. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) treatment guidelines. Available at: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/. Accessed 17 July 2020. [PubMed]

- 34. McCaw ZR, Kim DH, Wei LJ. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19—preliminary report. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:992–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dodd LE, Follmann D, Wang J, et al. Endpoints for randomized controlled clinical trials for COVID-19 treatments. Clin Trials 2020; 17:472–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.