ADDITIONAL CONTENT

An author video to accompany this article is available at: https://academic.oup.com/ndt/pages/author_videos.

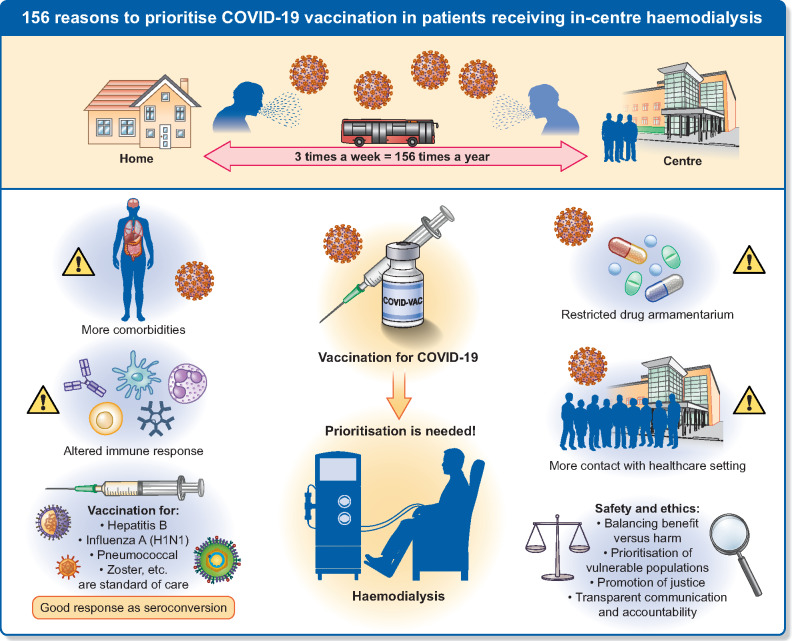

A timely analysis and call to action by the Council of the ERA-EDTA and the European Renal Association COVID-19 Database (ERACODA) Working Group has recently highlighted the extremely high burden of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection in chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients, who, compared with patients suffering from other major disorders, are at the highest risk to develop severe COVID-19 and to die from it [1]. The authors call for greater recognition of this risk and for inclusion of patients with CKD in clinical trials. Here, the European Dialysis (EUDIAL) Working Group issues a strong call for priority access to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccines for the most vulnerable group of patients with kidney disease: those receiving in-centre haemodialysis (ICHD) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Call of the EUDIAL Working Group to prioritize COVID-19 vaccination in patients receiving ICHD.

Living well with haemodialysis (HD) generally requires three sessions per week. For those receiving ICHD, this translates into at least 156 dialysis sessions per year, each one an unavoidable occasion with risk of exposure to COVID-19. ICHD carries the risk of contact with potentially infected health professionals, other high-risk patients or risks inherent to commuting. Recognition of the high risk of virus spread among patients on ICHD has driven reorganization of dialysis care delivery. Physical interventions (social distancing, barriers, personal protection) and strict infection control (triage, isolation) have been implemented to ensure the safety of patients and staff [2]. Recommendations to transition patients from in-centre to home dialysis to reduce their risk during the pandemic have not been clinically feasible for most patients receiving ICHD. ICHD in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 is complicated by requirements for strict infection control, patient isolation and dedicated staff, which puts dialysis centres under additional strain. Patients who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 but are not sick enough for hospital admission are managed in outpatient units to avoid overwhelming inpatient dialysis services. On arrival to the dialysis unit, patients with known COVID-19 are dialysed in an isolation room or on ‘COVID-19’ shifts, with dedicated staff equipped with adequate personal protective equipment. These patients require careful observation and monitoring, and a proportion requires subsequent admission [3].

Vulnerability in uraemic patients is a combination of intrinsic frailty, increased risk of infection (vascular access, exposure to infected individuals) and a high burden of comorbidities [1]. Although patients on dialysis have a similar overall high risk of death from COVID-19 to patients with kidney transplants [4], patients on HD and on the waiting list have a 2-fold higher risk of infection because of risk inherent to the HD process [5]. Age per se is a less significant risk factor among those on dialysis compared with the general population [1]. Younger adults, children on ICHD and their carers face high risks of exposure to infection but are unable to shield themselves at home, and children are unable to return to school. All patients receiving ICHD are therefore highly vulnerable [1].

In patients on HD, abnormalities in the immune response are characterized by abnormal activation and reduced function of the innate and adaptive immune systems, associated with a reduction in dendritic cells, skewed Th1/Th2 T-cell ratios, less T-cell activation and an increase in senescent, hyporeactive T cells [6]. These factors may contribute to relative hyporesponsiveness to vaccines in some patients. Concerns regarding potential vaccine hyporesponsiveness should not prevent patients on dialysis from receiving vaccinations, however. Indeed, multiple vaccines (influenza, pneumococci, hepatitis B, zoster, human papillomavirus, etc.) are standard of care in patients on HD [7]. The majority of patients do respond effectively: hepatitis B has been virtually eradicated in many countries through vaccination and hygiene practices. During the 2009 influenza A virus (H1N1) pandemic, vaccination was strongly recommended by the World Health Organization and led to seroconversion in 57–64.2% of patients on HD [8]. Vaccine dose was an independent factor predicting responsiveness in HD subjects [9]. Booster doses may therefore be required. These observations emphasize the urgent need to include patients receiving dialysis in vaccine trials. Importantly, patients on ICHD appear to seroconvert at a similar rate to the general population after SARS-CoV-2 infection, suggesting the likelihood of response to a vaccine [10]. In regions where the SARS-CoV-2 prevalence in the general population is high, high rates of asymptomatic seroconversion in patients were also observed [11]. Surveillance post-vaccination is advisable to identify vaccine non-responders among patients receiving ICHD, although a level of ‘herd immunity’ achieved through vaccination of patients and staff in dialysis units should confer some protection. Units will also need to plan for patients (or staff) who decline vaccination. It is important that such individuals should not be stigmatized. Strict adherence to physical protective measures remains necessary.

Current global recommendations suggest prioritization of healthcare workers at high risk, along with older adults [12]. Given the extreme vulnerability of patients receiving ICHD, there should be little doubt that dialysis staff meet the criteria for prioritization. Where the highly vulnerable patients receiving ICHD will fall along the prioritization spectrum is not yet clear.

From an ethical perspective, given that the vaccine supplies will be limited at least during the initial phases of vaccine roll-out, stewardship and accountability are required. Ethical principles underlying allocation decisions include (i) balancing benefit versus harm, (ii) prioritization of vulnerable populations, (iii) promotion of justice—meeting the needs of populations with disproportionate burdens, avoiding exacerbation of health inequities, fair vaccine distribution and (iv) transparent communication and accountability by decision-makers [12, 13]. Two major questions arise: (i) is the vaccine safe for patients on ICHD and (ii) should patients on ICHD be prioritized over other groups for vaccination?

The first question highlights a major inequity pervasive in most vaccine trials, where vulnerable patients are often excluded. Based on the experience with other vaccines, there are no reasons to expect higher risks of complications in patients receiving dialysis. Concerns regarding potential harm from induction of alloimmunity through vaccination in patients with or awaiting transplantation have not been confirmed. If the benefit versus risk ratio of the vaccine is considered to be favourable for other vulnerable patients, this should apply similarly to patients on ICHD [12–14]. Transparency is crucial. Patients must be fully informed about the limits of current safety data, as well as the reasons why vaccination is being strongly encouraged. As more vaccine candidates become approved, ongoing surveillance of efficacy and consequences in patients on dialysis may permit favouring one type of vaccine over another over time.

The second question about prioritization of patients on ICHD for vaccination over other patient groups is more complex. Dialysis and transplantation are the leading global risk factors for death from COVID-19. When matched for age and sex, however, patients with kidney transplants have an almost 30% higher risk of death compared with those on dialysis [4]. Patients receiving ICHD are, however, highly vulnerable because in comparison with patients with transplants or with other chronic diseases, they are not able to shield optimally. If initial dose availability is limited, the elevated risk of both infection and death in patients receiving ICHD would justify their initial prioritization, followed as closely as possible by patients living with transplants and advanced CKD. Patients receiving dialysis at home, whether peritoneal dialysis or HD, have similar intrinsic risk, and are only less vulnerable than patients on ICHD because they do not travel frequently for care. These patients should therefore also be prioritized as soon as supplies permit. Furthermore, given their multiple comorbidities and high frailty scores, patients receiving dialysis may not be considered for limited intensive care beds if triage protocols are implemented [15]. Thus, in accepting potentially limiting access to treatment for severe COVID-19 in patients receiving dialysis, it can be argued that society ‘owes’ optimal preventive measures to this population. Such prioritization based on reciprocity would apply to all high-risk patient groups that may be ineligible for intensive care. Justice demands that their disadvantage should not be exacerbated through delay in vaccination.

In terms of justice, as soon as a country decides to allocate vaccines for patients on ICHD, vaccine distribution must be equitable, between units and between patients within units. There should be no favouring of access based on unacceptable criteria such as private versus public dialysis units or patient age. The dose, efficacy and long-term safety of COVID-19 vaccines in children are not known, and vaccine trials have only just extended to the paediatric population. Whether vaccines should be withheld in children receiving ICHD based on the lack of data, or whether they should be prioritized for vaccination, must be discussed. Strong consideration must be given to vaccination of parents of children receiving ICHD.

In conclusion, it is clear that patients receiving ICHD are highly vulnerable to infection, severe disease and death from COVID-19, and are likely to respond to vaccination. They represent a vulnerable population that is additionally disadvantaged due to lack of inclusion in clinical trials, and potential ineligibility for intensive care should they become severely ill. There remain many ‘known unknowns’ in the safety, efficacy and duration of antibody response to the SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with kidney failure. Clinical trials to monitor the antibody response to vaccination and safety in these patients are imperative to promote transparent evidence-based decision-making. Clinically and ethically, the grounds to support vaccination are strong. We therefore strongly call for the inclusion of patients on ICHD, and subsequently all patients with transplants and those receiving home dialysis, in priority risk groups for early vaccination against SARS-CoV-2.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Sandip Mitra, Adrian Covic, Dimitrios Kirmizis and Vassilios Liakopoulos are Board Members of the EUDIAL Working Group.

FUNDING

No funding was received for the drafting of this article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

This publication includes no original data except those extracted from the cited publications.

REFERENCES

- 1. ERA-EDTA Council, ERACODA Working Group. Chronic kidney disease is a key risk factor for severe COVID-19: a call to action by the ERA-EDTA. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2021; 36: 87–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Basile C, Combe C, Pizzarelli F et al. Recommendations for the prevention, mitigation and containment of the emerging SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic in haemodialysis centres. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2020; 35: 737–741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Medjeral-Thomas NR, Thomson T, Ashby D et al. Cohort study of outpatient hemodialysis management strategies for COVID-19 in North-West London. Kidney Int Rep 2020; 5: 2055–2065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jager KJ, Kramer A, Chesnaye NC et al. Results from the ERA-EDTA Registry indicate a high mortality due to COVID-19 in dialysis patients and kidney transplant recipients across Europe. Kidney Int 2020; 98: 1540–1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thaunat O, Legeai C, Anglicheau D et al. IMPact of the COVID-19 epidemic on the mORTAlity of kidney transplant recipients and candidates in a French Nationwide registry sTudy (IMPORTANT). Kidney Int 2020; 98: 1568–1577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eleftheriadis T, Antoniadi G, Liakopoulos V et al. Basic science and dialysis: disturbances of acquired immunity in hemodialysis patients. Semin Dial 2007; 20: 440–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Haddiya I. Current knowledge of vaccinations in chronic kidney disease patients. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis 2020; 13: 179–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Broeders NE, Hombrouck A, Lemy A et al. Influenza A/H1N1 vaccine in patients treated by kidney transplant or dialysis: a cohort study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 6: 2573–2578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dikow R, Eckerle I, Ksoll-Rudek D et al. Immunogenicity and efficacy in hemodialysis patients of an AS03(A)-adjuvanted vaccine for 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1): a nonrandomized trial. Am J Kidney Dis 2011; 57: 716–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mahalingasivam V, Tomlinson L. The seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in patients on haemodialysis. Nat Rev Nephrol 2020; 10.1038/s41581-020-00379-y (22 January 2021, date last accessed) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Anand S, Montez-Rath M, Han J et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in a large nationwide sample of patients on dialysis in the USA: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2020; 396: 1335–1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. WHO SAGE Roadmap for Prioritizing Uses of COVID-19 Vaccines in the Context of Limited Supply [Internet], 2020. [cited 22 January 2021]. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/who-sage-roadmap-for-prioritizing-uses-of-covid-19-vaccines-in-the-context-of-limited-supply (11 December 2020, date last accessed)

- 13. Bell BP, Romero JR, Lee GM. Scientific and ethical principles underlying recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for COVID-19 vaccination implementation. JAMA 2020; 324: 2025–2026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Persad G, Peek ME, Emanuel EJ. Fairly prioritizing groups for access to COVID-19 vaccines. JAMA 2020; 324: 1601–1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jöbges S, Vinay R, Luyckx VA et al. Recommendations on COVID‐19 triage: international comparison and ethical analysis. Bioethics 2020; 34: 948–959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This publication includes no original data except those extracted from the cited publications.