Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) resulted into a global pandemic and continues to thrive until vaccines have been successfully developed and distributed around the world. The outcomes of COVID-19 contaminations range from death to minor health-related complaints. Furthermore, and not less significant, the increasing pressure on local as well as global health care is rising. In The Netherlands but also in other countries, further intensified regulations are introduced in order to contain the second wave of COVID-19, primarily to limit the number contaminations but also to prevent the health care professionals for giving in to the rising pressure on them. The results of the campaign for health care professionals in The Netherlands show that health care professionals are increasingly searching for information regarding psychological symptoms such as feeling of uncertainty, pondering and advice regarding the support of care teams. In this short update, we provide the results of the previous campaign and stress the importance of support after COVID-19 based on these results.

The Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and its pandemic has become a serious threat for public mental health and concerns many countries all over the world.1 Preventive measures are introduced by governments all over the world and people’s attitude towards these measures vary.2 Such non-therapeutic measures (e.g. lockdown, partial lockdown, social distancing, self-isolation and others) are essential in order to limit the further continuation of the pandemic,3 but one must not forget to address the therapeutic measures as, perhaps equally, important. Indisputably, COVID-19 has major impact on mental health and decline of well-being4 during (partly) lockdown measures, social distancing and other necessary taken measures. As a result of the pandemic, people experience deterioration in mental and physical health as they in general accept limitation regarding mobility, which in turn may lead to loneliness or social isolation.5,6 Since the pandemic continues, the pressure on health care professionals continues as well, which calls for therapeutic support in case of, e.g. exhaustion. Moreover, such support should also be developed for the general population who experience symptoms after COVID-19.

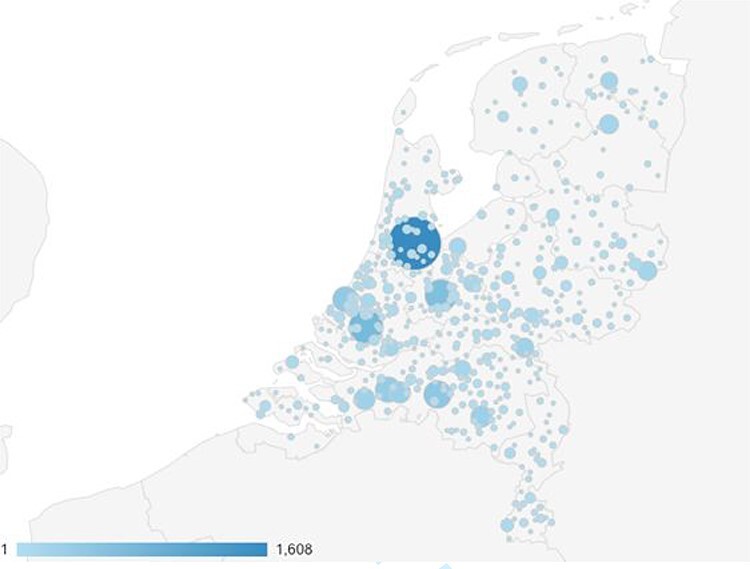

Incontrovertibly, health care professionals are exposed to long-lasting elevated psychological stress during this continuing pandemic, which also results in increased reports of anxiety and depression,7 in its turn contributing to an elevated psychological burden across populations worldwide in health care professionals. Earlier, the situation regarding the health care professionals in The Netherlands was stressed8 and the necessity of a protocol to prevent the incapacitation of these professionals was stressed by setting up a national campaign.9 Throughout The Netherlands, individuals are increasingly accessing the website in the last couple of months (see Fig. 1 which displays the use of the website). More specifically, during the past month (November), visits of the website’s campaign increase rapidly and information regarding how to cope with feelings of sadness, exhaustion and tips for mental support for health care teams is frequently visited on the website. Furthermore, the number of visits of the website increased exponentially (up to 180% compared with previous months). These signs are pivotal and should be taken seriously since the pandemic continues and the workload of these professionals will remain to increase overtime.

Fig. 1 .

Users of the website https://vergeetjezelfniet.nu in The Netherlands.

Psychosocial support for health care professionals

Feelings of loneliness or social isolation are reported by health care workers10 so psychosocial support is necessary to prevent incapacitation due to, e.g. exhaustion. It is promising to see that the support of health care professionals gains attention (e.g. Frias et al.10) and the development of protocols for this profession is increasing, which looks promising. Since the pandemic will continue for a while, at least until the release of a vaccine, the pressure on health care professionals will remain present for a while.

Psychosocial support after COVID-19

Furthermore, studies conducted in the USA also show clear signs of the harmful consequences both mentally and psychologically of COVID-19 in the general population (e.g. anxiety and depression).11 Results from The Netherlands are currently collected12 but are expected to show similar results. These studies stress the necessity of the development of treatment protocols for individuals among the general population. Moreover, two types of individuals can be identified, individuals who suffer from the consequences after a COVID-19 infection and individuals who suffer from consequences of COVID-19 pandemic (e.g. anxiety for infection, experience feelings of loneliness) and/or loss of loved ones. The consequences of COVID-19 in both groups are persistent.13–15 Psychological symptoms of the first group of individuals consist of post-traumatic stress disorder,16 fear of stigma and/or infection, sleep and/or mood disorders,17 persistent cognitive symptoms18 and feeling of loneliness due to social isolation.19 It is key that both are treated adequately and, more importantly, as quickly as possible after clinical signs are present to prevent any long-term consequences. A treatment program called CO-Fit 19 is currently introduced in the South of the Netherlands and individuals from both groups are getting signed up20.

The consequences of COVID-19 infection but also due to the COVID-19 pandemic regarding mental health are clear. Psychosocial support is pivotal in these times where the COVID-19 infections increase, especially for health care professionals for which the pressure and heightened workload will continue. Furthermore, two types of treatment options can be identified for individuals from the general population. Firstly, psychosocial support for individuals who suffer from the consequences after COVID-19 infection is crucial. Secondly, support for individuals who suffer from the results of the COVID-19 pandemic is also stressed. These three therapeutic elements in psychosocial support regarding COVID-19 should be adapted in general health care practice as quickly as possible to prevent any long-term consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic as the consequences for mental health should not be underestimated.

Conflicts of interest

We have no competing interests.

Lars Vroege de, Phd, General Health Psychologist

Anneloes Broek van den, Phd, Clinical Psychologist Specialist, Psychotherapist, Psychotraumatherapist

Contributor Information

Lars de Vroege, Tranzo scientific center for Care and Welbeing, Tilburg University, Tilburg, The Netherlands; Clinical Centre of Excellence for Body, Mind, and Health, GGz Breburg, Tilburg, The Netherlands.

Anneloes van den Broek, Department of Anxiety and Depression, GGz Breburg, Tilburg, The Netherlands.

References

- 1.Zhong B-L, Luo W, Li H-M et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Int J Biol Sci 2020;16(10):1745–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azlan AA, Hamzah MR, Sern TJ et al. Public knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19: a cross-sectional study in Malaysia. PLoS One 2020;15(5):e0233668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anwar S, Nasrullah M, Hosen MJ. COVID-19 and Bangladesh: challenges and how to address them. Front Public Health 2020;8:154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . Facing Mental Health Fallout from the Coronavirus Pandemic. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/facing-mental-health-fallout-from-the-coronavirus-pandemic (2 December 2020, date last accessed).

- 6.Vindegaard N, Benros ME. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun 2020;89:531–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan BYQ, Chew NWS, Lee GKH et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in Singapore. Ann Intern Med 2020;173:317–20.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Vroege L, van den Broek A. Mental support for health care professionals essential during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Public Health 2020;42(4):679–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Vroege L, Gribling G, van den Broek A. Don't forget about yourself when taking Care of Others: mental health support for health care professionals during the COVID-19 crisis [article in Dutch]. Tijdschr Psychiatr 2020;62(6):424–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Temsah MH, Al-Sohime F, Alamro N et al. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in a MERS-CoV endemic country. J Infect Public Health 2020;13:877–82.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frias CE, Cuzco C, Martin CF et al. Resilence and emotional support in health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J PSychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 2020;58(6):5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Center for Health Statistics Household Pulse Survey. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/mental-health.htm.

- 13.Van Helvoort MA, van Dee V, Dirks A et al. Course of COVID-19 infections and impact on mental health; setting up a national case register [article in Dutch]. Tijdsch Psychiatrie 2020;62(9):739–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Troyer EA, Kohn JN, Hong S. Are we facing a crashing wave of neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19? Neuropsychiatric symptoms and potential immunologic mechanisms. Brain Behav Immun 2020;87:34–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torales J, O’Higgins M, Castaldelli-Maia JM et al. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2020;66(4):317–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu N, Zhang F, Wei C et al. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: gender differences matter. Psych Res 2020;287:112921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun 2020;88:901–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wenting AMG, Gruters A, van Os YGHW et al. COVID-19 pandemic; post intensive care syndrome (PICS) and scoping review regarding brain effects. https://www.lvmp.nl/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Artikel-COVID-19-PICS-en-Breineffecten.pdf.

- 19.Van Amelsvoort TAMJ. Loneliness is unhealthy [article in Dutch]. Tijdsch Psychiatrie 2020;62(10):824–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Vroege, L, Bruins, D., Van den Broek, A. Results of the campaign and treatment offer of mental are during the COVID-19 pandemic [Article in Dutch]. Tijdsch Psychiatrie, under review.