Abstract

Background

To determine if dried blood spot specimens (DBS) can reliably detect severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) antibodies, we compared the SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody response in paired serum and eluates from DBS specimens.

Methods

A total of 95 paired DBS and serum samples were collected from 74 participants (aged 1–63 years) as part of a household cohort study in Melbourne, Australia. SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies specific for the receptor-binding domain (RBD) and S1 proteins between serum and eluates from DBS specimens were compared using an FDA-approved ELISA method.

Results

Among the 74 participants, 42% (31/74) were children and the rest were adults. A total of 16 children and 13 adults were SARS-CoV-2 positive by polymerase chain reaction. The IgG seropositivity rate was similar between serum and DBS specimens (18.9% (18/95) versus 16.8% (16/95)), respectively. Similar RBD and S1-specific IgG levels were detected between serum and DBS specimens. Serum IgG levels strongly correlated with DBS IgG levels (r = 0.99, P < 0.0001) for both SARS-CoV-2 proteins. Furthermore, antibodies remained stable in DBS specimens for >3 months.

Conclusions

DBS specimens can be reliably used as an alternative to serum samples for SARS-CoV-2 antibody measurement. The use of DBS specimens would facilitate serosurveillance efforts particularly in hard-to-reach populations and inform public health responses including COVID-19 vaccination strategies.

Keywords: infectious disease, methods, public health

Introduction

The true level of exposure to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) within a population or community is often underestimated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) measurements alone.1 One of the reasons for this is the large number of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases (up to 40%) being asymptomatic,2 which include a large proportion of children (70%) who often present with mild illness or are asymptomatic.3 As a result, many cases are often missed or not being tested. Measuring the size, extent and heterogeneity of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is crucial in providing a swift and informed public health response.

Serosurveillance can provide estimates of cumulative exposure to SARS-CoV-2 by geographic area and population demographics and allows the progress of the pandemic, as well as the public health response, to be monitored. In addition, with the roll out of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination programs, serosurveillance can also be used to track vaccine immunity. However, the large amount of fieldwork and manpower required for specimen collection and cold-chain transportation for serosurveillance is challenging. During this pandemic, restrictions in movement and physical contact have also meant that collecting venous blood samples for serological testing has been more difficult. The use of dried blood spot (DBS) specimens would provide a more feasible approach to serosurveillance studies of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies but requires evaluation. To determine if DBS specimens can be used to reliably detect SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies, we compared serum and eluates from DBS specimens collected as part of a household contact study.

Methods

The study samples were collected as part of a household cohort study in Melbourne, Australia. Participants who had a SARS-CoV-2 positive test (nasal/throat swab PCR-positive) and their household close contacts were recruited at the Royal Children’s Hospital between 10 May and 29 July 2020. Venous blood samples were collected from each participant following informed consent. A subset of samples (N = 95 from 74 participants) had an aliquot of blood (50 μl/spot × 4 spots) spotted onto a Guthrie card filter paper (Whatman™ 903 filter paper) as DBS for this study. This study was approved by the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC): HREC/63666/RCHM-2019. We used the Mount Sinai Laboratories (USA) ELISA method4 to determine antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain (RBD) and Spike subunit 1 (S1), the main antigen targets on the virus and are used in most serological assays (Details of DBS specimen processing, ELISA method and statistical analysis are provided in the Supplementary).

Results

Out of the 74 participants, 31 (41.9%) were children (1–18 years old), with 16 (51.6%) confirmed positive for SARS-CoV-2. The rest of the participants were adults aged 19–63 years old (43/74, 58.1%), with 13 (30.2%) confirmed positive (refer to Supplementary Table 1 for participants characteristics). All infected participants were either asymptomatic or had mild symptoms. A total of 21 participants had serial samples, but most were seronegative.

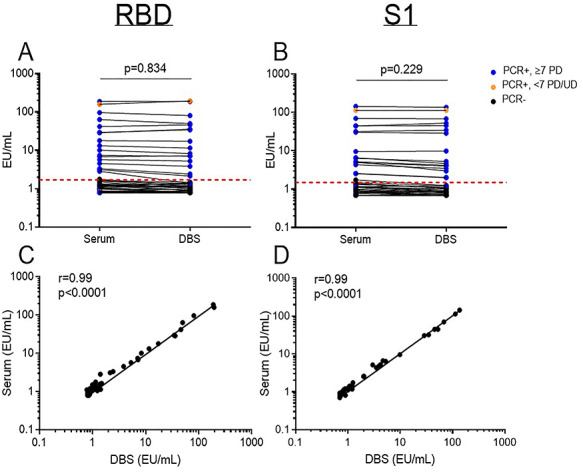

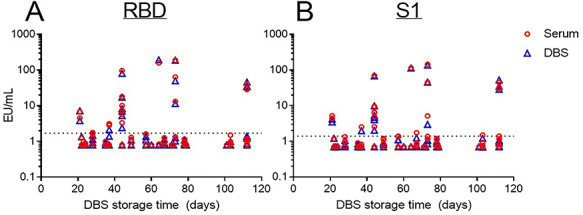

The IgG seropositivity rate to the SARS-CoV-2 RBD or S1 were not significantly different between serum and DBS specimens (18.9% (18/95) versus 16.8% (16/95)); two individuals were borderline seropositive on serum but not DBS. There was no significant difference in the RBD- and S1-specific IgG antibody levels between serum and DBS specimens (Fig. 1A and B; Supplementary Fig. S1). Moreover, both the RBD and S1-specific IgG antibody levels measured from the DBS specimens strongly correlated with their paired serum samples (r = 0.99, P < 0.0001; Fig. 1C and D). To determine if DBS storage duration had a negative effect on SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG measurement, we compared paired serum and DBS specimens based on their storage duration prior to assay. There was no effect of DBS storage time on the detection of SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies and this was observed for samples up to 112 days (Fig. 2A and B); no significant difference was observed in measured RBD- and S1-specific IgG antibody levels for paired samples stored for ≤30 or >30 days (Supplementary Fig S2).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of serum and dried blood spot (DBS) ELISA for the receptor-binding domain (RBD) and spike domain 1 (S1) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Concentration of (A) RBD- and (B) S1-specific IgG paired analysis. Correlation of (C) RBD- and (D) S1- specific IgG between serum and DBS specimens. Data are presented as mean ± 95% CI and each point is an individual sample. The dotted line represents the cut-off for seropositivity based on pre-pandemic sera plus two standard deviations. PCR+/−: SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction status. PD: post-PCR diagnosis. UD: undetermined. EU: ELISA Units. r: correlation coefficient.

Fig. 2.

Effect of DBS storage duration on the measurement of (A) RBD- and (B) S1- specific IgG response for all DBS specimens (blue) and their corresponding serum samples (red) based on DBS storage time (n = 95) Paired t-test and Pearson’s correlation analysis were performed for IgG concentrations and correlation analysis, respectively. The dotted line represents the cut-off for seropositivity based on pre-pandemic sera plus two standard deviations.

Discussion

Our results indicate that DBS specimens can be reliably used as an alternative to serum samples for SARS-CoV-2 antibody measurement, given the strong correlation observed between DBS specimens and serum samples. Furthermore, we found that DBS specimens remained stable for at least 3 months, enabling the conduct of serosurveillance efforts more broadly.

Advantages of DBS include (1) requires less blood volume, which is particularly important in paediatric settings, (2) the cost is relatively inexpensive, (3) long-term stability of sample without need for refrigeration and (4) can be transported by regular post. While our study did not assess the feasibility of sample collection using finger-prick, we believe that this is unlikely to affect our results given the utility of finger-prick sampling for other studies.5–8 Therefore, our data suggest that the combination of finger-prick sampling and DBS collection could be used to facilitate serosurveillance efforts for SARS-CoV-2 in a similar way that they have been for monitoring infectious disease control of measles, hepatitis B and hepatitis C.6,7 Such an approach would be valuable for SARS-CoV-2 serosurveys particularly in hard-to-reach populations.

Our results confirm previous findings on the utility of DBS for SARS-CoV-2 antibody measurements,5,8,9 but also extend these findings in several ways by (1) demonstrating the stability of DBS specimens, (2) using an established assay that has been granted Food and Drug Administration Emergency Use Authorization status, (3) using a standardized reference panel serum provided by National Institute for Biological Standards and Controls (UK) and the World Health Organization Solidarity II group and (4) including paediatric samples.

Lateral flow immunoassays (LFIA) and other rapid tests offer the promise of delivering antibody testing at scale, but the performance of currently available assays for SARS-CoV-2 is highly variable and with lower sensitivity compared to ELISA-based platforms.10 Therefore, the convenient sampling of DBS and the use of ELISA may provide a more accurate measurement than currently available rapid tests, particularly for samples that have low antibody levels.

Understanding the extent of viral transmission and population immunity is critical to inform public health responses against this pandemic. This includes the easing of lockdown restrictions, re-opening of schools, understanding herd immunity and informing vaccination strategies. Our findings suggest that DBS collection is a reliable strategy for measurement of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, and is a simple and low-cost approach for global COVID-19 serosurveillance efforts, including measuring population immunity following COVID-19 vaccine rollout programs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the study participants and families for their involvement in this study. We also acknowledge the MCRI Biobanking service for their help in processing the samples.

Zheng Quan Toh, Dr

Rachel A Higgins, Mrs

Jeremy Anderson, Mr

Nadia Mazarakis, Ms

Lien Anh Ha Do, Dr

Karin Rautenbacher, Ms

Pedro Ramos, Mr

Kate Dohle, Ms

Shidan Tosif, Dr

Nigel Crawford, Prof

Kim Mulholland, Prof

Paul V Licciardi, A/Prof

Contributor Information

Zheng Quan Toh, Infection and Immunity, Murdoch Children's Research Institute, Melbourne, Victoria 3052, Australia; Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia.

Rachel A Higgins, Infection and Immunity, Murdoch Children's Research Institute, Melbourne, Victoria 3052, Australia.

Jeremy Anderson, Infection and Immunity, Murdoch Children's Research Institute, Melbourne, Victoria 3052, Australia; Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia.

Nadia Mazarakis, Infection and Immunity, Murdoch Children's Research Institute, Melbourne, Victoria 3052, Australia; Faculty of Veterinary and Agricultural Sciences, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia.

Lien Anh Ha Do, Infection and Immunity, Murdoch Children's Research Institute, Melbourne, Victoria 3052, Australia; Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia.

Karin Rautenbacher, Department of General Medicine, The Royal Children’s Hospital, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia.

Pedro Ramos, Infection and Immunity, Murdoch Children's Research Institute, Melbourne, Victoria 3052, Australia.

Kate Dohle, Infection and Immunity, Murdoch Children's Research Institute, Melbourne, Victoria 3052, Australia.

Shidan Tosif, Infection and Immunity, Murdoch Children's Research Institute, Melbourne, Victoria 3052, Australia; Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia; Department of General Medicine, The Royal Children’s Hospital, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia.

Nigel Crawford, Infection and Immunity, Murdoch Children's Research Institute, Melbourne, Victoria 3052, Australia; Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia; Department of General Medicine, The Royal Children’s Hospital, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia.

Kim Mulholland, Infection and Immunity, Murdoch Children's Research Institute, Melbourne, Victoria 3052, Australia; Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia; Department of Infectious Disease and Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London WC1E 7HT, UK.

Paul V Licciardi, Infection and Immunity, Murdoch Children's Research Institute, Melbourne, Victoria 3052, Australia; Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia.

Funding

This work was supported by the Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation and the MCRI Infection and Immunity Theme, as well as the Victorian Government’s Medical Research Operational Infrastructure Support Program. P.V.L. is supported by NHMRC Career Development Fellowship.

Conflict of Interest

N.C. received funding from the National Institute of Health for influenza and COVID19 research. All other authors reported no conflicts of interests.

Data Availability Statements

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.

References

- 1. Gudbjartsson DF, Norddahl GL, Melsted P et al. Humoral immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in Iceland. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1724–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Oran DP, Topol EJ. Prevalence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med 2020;173:362–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Qiu H, Wu J, Hong L et al. Clinical and epidemiological features of 36 children with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Zhejiang, China: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20:689–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Amanat F, Stadlbauer D, Strohmeier S et al. A serological assay to detect SARS-CoV-2 seroconversion in humans. Nat Med 2020;26:1033–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McDade TW, McNally EM, Zelikovich AS et al. High seroprevalence for SARS-CoV-2 among household members of essential workers detected using a dried blood spot assay. PLoS One 2020;15:e0237833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Centers for Disease C, Prevention . Recommendations from an ad hoc Meeting of the WHO Measles and Rubella Laboratory Network (LabNet) on use of alternative diagnostic samples for measles and rubella surveillance. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008; 57:657–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yamamoto C, Nagashima S, Isomura M et al. Evaluation of the efficiency of dried blood spot-based measurement of hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus seromarkers. Sci Rep 2020;10:3857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morley GL, Taylor S, Jossi S et al. Sensitive detection of SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies in dried blood spot samples. Emerg Infect Dis 2020;26:2970–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thevis M, Knoop A, Schaefer MS et al. Can dried blood spots (DBS) contribute to conducting comprehensive SARS-CoV-2 antibody tests? Drug Test Anal 2020;12:994–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Flower B, Brown JC, Simmons B et al. Clinical and laboratory evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 lateral flow assays for use in a national COVID-19 seroprevalence survey. Thorax 2020;75:1082–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.