To the Editor,

It has been thought that ulcerative colitis (UC) may be triggered by environmental factors, such as infections, in genetically susceptible patients.1 We report on a patient with de novo UC onset after SARS-CoV-2 infection.

In May 2020, a nonsmoking male patient aged 55 years with an uneventful medical history was diagnosed with COVID-19 pneumonia. After treatment with steroids, azithromycin, and heparin, inflammatory markers rapidly normalized; 24 days later, two consecutive swabs resulted negative and he was discharged. One month later, he was completely asymptomatic, showing high antispike antibody titers (IgG, 89.4 AU/mL).

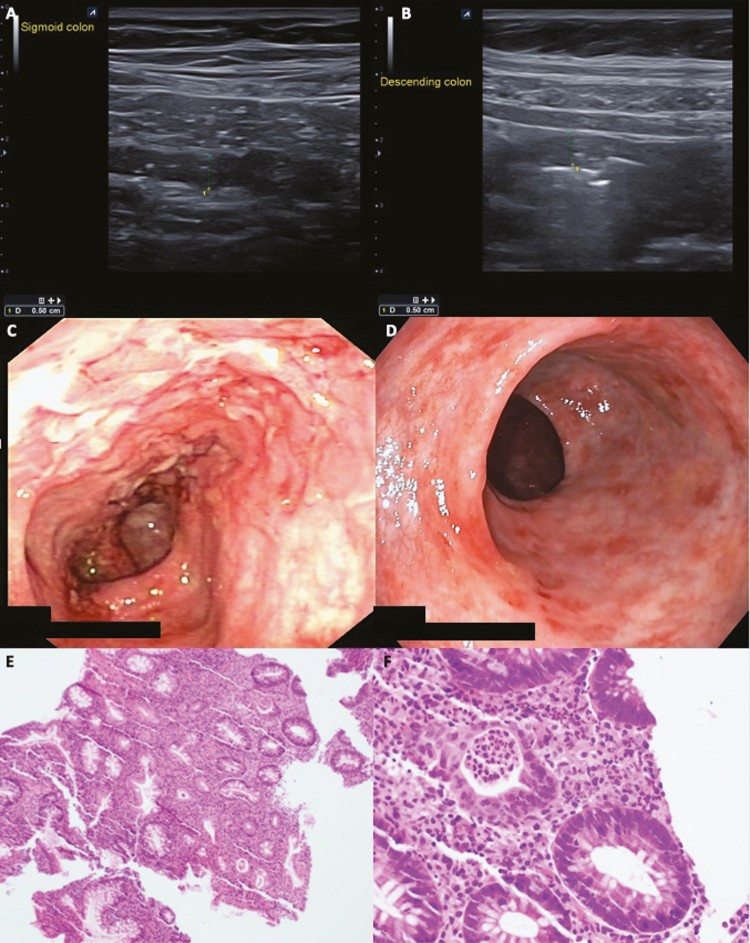

In August, the patient developed abdominal pain and diarrhea. Shortly afterward, his symptoms worsened with severe abdominal pain and chronic bloody diarrhea (15 bowel movements per day). In September 2020, he was admitted to our gastroenterology department. After ruling out infections, including SARS-CoV-2, a diagnosis of de novo UC was made on the basis of bowel sonography (Figs. 1A, B), endoscopy (Figs. 1C, D), and histology (Figs. 1E, F).

FIGURE 1.

Small bowel ultrasound showing increased sigmoid (A) and descending (B) colon thickness. Endoscopic view showing an extensive colitis with ulcerations, erosions, mucosal friability, and spontaneous bleeding at rectosigmoid junction (C) and descending colon (D). Histopathology showing active inflammation with cryptitis and crypt abscesses, crypt architectural distortion, and ulcerations (E-F).

Although SARS-CoV-2 infection most commonly affects the respiratory tract, it also causes gastrointestinal symptoms.2 In fact, the gastrointestinal tract may be an extrapulmonary site for virus replication, leading to the deregulation of the gut–liver axis in these patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection.3 The angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor is considered the key used by SARS-CoV-2 to enter the host3: Highly expressed in both the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts, ACE2 plays a pivotal role in directing intestinal inflammation and microbiota.3 Through these mechanisms, SARS-CoV-2 alters the gut microbiota, leading to a reduction in Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Eubacterium and to an increase in Corynebacterium and Ruthenibacterium2: all these SARS-CoV-2-induced modifications in the gut microbiota reflect those described in patients who develop UC. Similarly, the overexpression of ACE2 induced by SARS-CoV-2 has been associated with increased colonic inflammation in UC.3

Therefore, we can speculate that SARS-CoV-2 infection, acting on ACE2 expression and gut microbiota composition in genetically susceptible patients, could be a trigger for de novo UC, as described in our patient. Recently, 2 patients with UC onset during SARS-CoV-2 infection have been reported.4, 5 Our patient had neither a significant history of intestinal disease nor gastrointestinal symptoms suspicious for inflammatory bowel disease before his symptoms appeared. Furthermore, he did not experience gastrointestinal symptoms during his SARS-CoV-2 infection, thus making previously undiagnosed inflammatory bowel disease improbable.

In conclusion, several pathogenetic mechanisms could potentially lead to UC onset after SARS-CoV-2 infection, including ACE2 overexpression and gut microbiota alterations. Clinicians will need to pay close attention to the appearance of red flags in patients with a previous SARS-CoV-2 infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1. Mann EA, Saeed SA. Gastrointestinal infection as a trigger for inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2012;28:24–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mohandas S, Vairappan B. SARS-CoV-2 infection and the gut-liver axis. J Dig Dis. Published online October 24, 2020. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xiao F, Tang M, Zheng X, et al. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1831–1833.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Calabrese E, Zorzi F, Monteleone G, et al. Onset of ulcerative colitis during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52:1228–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Taxonera C, Fisac J, Alba C. Can COVID-19 trigger de novo inflammatory bowel disease? Gastroenterology. Published November 19, 2020. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]