Abstract

Approaches toward new therapeutics using disease genomics, such as genome-wide association study (GWAS), are anticipated. Here, we developed Trans-Phar [integration of transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS) and pharmacological database], achieving in silico screening of compounds from a large-scale pharmacological database (L1000 Connectivity Map), which have inverse expression profiles compared with tissue-specific genetically regulated gene expression. Firstly we confirmed the statistical robustness by the application of the null GWAS data and enrichment in the true-positive drug–disease relationships by the application of UK-Biobank GWAS summary statistics in broad disease categories, then we applied the GWAS summary statistics of large-scale European meta-analysis (17 traits; naverage = 201 849) and the hospitalized COVID-19 (n = 900 687), which has urgent need for drug development. We detected potential therapeutic compounds as well as anisomycin in schizophrenia (false discovery rate (FDR)-q = 0.056) and verapamil in hospitalized COVID-19 (FDR-q = 0.068) as top-associated compounds. This approach could be effective in disease genomics-driven drug development.

Introduction

Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have identified thousands of genomic loci associated with human complex traits (1). Associations identified by GWASs would reveal the mechanism of disease susceptibility and novel clinical approaches, such as the identification of novel therapeutic targets and drug repositioning. Recent studies have shown that the success probability of a project whose drug target was supported by human genome information is about twice as high as that of a project without its support (2,3); therefore, the utilization of human genetics in driving drug development is anticipated. Genetics-led approaches for new therapeutics have been performed in recent years (4–6).

Despite the success of GWASs, the biological functions of the majority of the identified genomic loci are elusive. Nearly 90% of the GWAS loci are lying in the non-coding regions (7), which are enriched in tissue- or cell-type-specific transcriptional regulatory regions involved in disease susceptibility (8). These results suggest that causal variants influence disease susceptibility by altering cell-type-specific regulatory elements, which result in altering gene regulation mechanisms, such as gene expression profiles. Recently, statistical methods to integrate GWAS results with the functional genomics data, such as quantitative trait loci (eQTL) data (9), have been developed. Transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS) is a method that integrates GWAS loci and eQTL data, such as the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project data (10) and statistically predicts trait-gene expression relationships that are called as genetically regulated gene expression (GREx) (11,12). TWAS has identified novel candidate genes significantly associated with disease susceptibility in a cell-type-specific way and yielded functional insights into disease susceptibility (13,14), but few of these insights have been directly utilized for pharmacological applications, such as drug discovery. Recent reports have shown that expression signatures of human diseases, such as differentially expressed genes (DEGs) by comparing disease samples and normal tissue samples, were applied to identify compounds whose perturbations were correlated on the transcriptomic level (15). The Connectivity Map (CMap) L1000 library is a public database in pharmacology, which contains large transcriptomic profiles of the dozens of cultivated cell lines treated with tens of thousands of bioactive compounds, and has been utilized to compare to disease signature and identify novel drugs or their mechanistic actions (16). However, there exist few reports utilizing GREx as an expression signature to comprehensively detect compounds from large-scale databases.

In this study, we have hypothesized that compounds, which have inverse effects in gene expression profiles when compared with GREx from common diseases, could be detected as potential drug candidates that are effective for disease treatment. Here, we constructed the GWAS-TWAS-compound library integration pipeline software (Trans-Phar; integration of transcriptome-wide association study and pharmacological database). This software conducts in silico screening of the compounds from the CMap L1000 library, which have an inverse correlation with the GREx estimated from the inputted GWAS summary statistics. The features of our pipeline software are as follows: (1) large-scale compound data source incorporated in our pipeline enables the detection of compounds on a broad scale and (2) 13 tissue- or/and cell-type categories are incorporated, which are assigned based on the 29 GTEx tissues used as the eQTL data in TWAS and on the 77 cell types from the CMap L1000 library database. This enables to detect compounds that affect tissue- or cell-type category-specific manners. We applied Trans-Phar to the UK-Biobank GWAS summary statistics covering a broad range of human traits and diseases (17,18) and to large-scale European GWAS meta-analysis summary statistics. Our results demonstrated that true-positive disease–drug relationships and potential novel drug or drug target candidates for inputted disease GWAS summary statistics were successfully detected.

Results

Overview of GWAS-TWAS-compound library integration pipeline

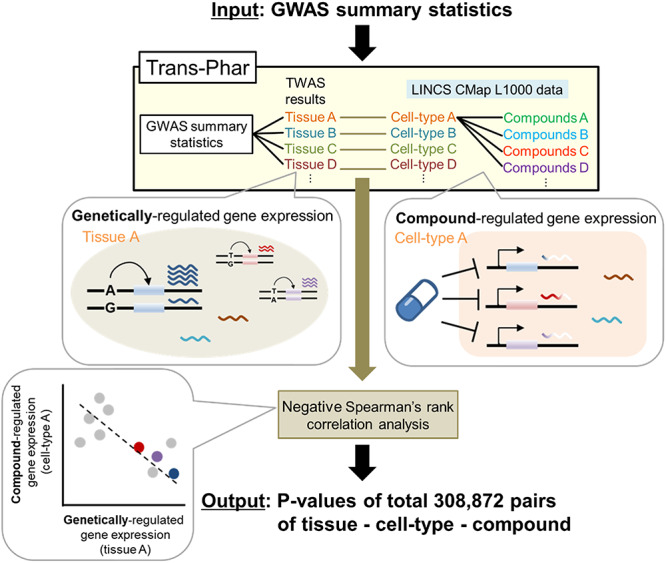

We hypothesized that compounds, which have an inverse effect in the gene expression profiles (i.e. negative correlation) when compared with GREx estimated from the common disease GWAS, could be identified as potential drug candidates effective for disease treatment. Here, we constructed a GWAS-TWAS-compound library integration pipeline. The overview of our method is shown in Figure 1. The method consists of the following three steps. Step 1: we performed TWAS to predict GREx, which contained predicted up-regulated and down-regulated genes concerning each inputted GWAS summary statistics of the disease or trait. We chose the 44 tissues GTEx version 7 eQTL data for the TWAS analysis, whose sample sizes were >100. Then, we obtained top-ranked genes whose absolute values of the TWAS Z-scores were on the top 10%, which we defined as genes with drastically changed expression levels among GREx. Step 2: we performed negative Spearman’s rank correlation analysis for the gene expression changes (Z-score) between top-ranked genes from the GREx and LINCS CMap L1000 library data, which consist of 308 872 pairs of compound and compound-perturbed cell-type gene expression change data that belonged to 13 tissue- or/and cell-type categories (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1). Step 3: we obtained output statistics as P-values from the negative Spearman’s rank correlation analysis. Each of which corresponds to a correlation P-value between the top-ranked genes from the TWAS of a GTEx tissue and compound-perturbed gene expression change in a specific tissue or cell-type category. This pipeline (named Trans-Phar) was publicly available at GitHub (https://github.com/konumat/Trans-Phar). Our pipeline software requires the formatted GWAS summary statistics as the input data and then outputs P-values and BH-adjusted false discovery rate (FDR)-q corresponding to each set of TWAS tissue-CMap L1000 library cell-type-compound (at a specific dose and at a specific time point).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the Trans-Phar framework of GWAS-TWAS-compound library integration. Step 1: TWAS is performed to predict GREx per GTEx tissue using GTEx version 7 eQTL data concerning the inputted GWAS summary disease or trait. Step 2: negative Spearman’s rank correlation analyses are performed using the top 10% of GREx per tissue and the LINCS CMap L1000 library data (cell-type- and cell-perturbed-compound pairs) for every tissue- or/and cell-type category. Step 3: Compounds that inversely correlate with GREx from each tissue with statistical significance are outputted, and their correlation-detected tissues and cell types are also outputted.

Evaluation of the integration pipeline

To validate the robustness of our pipeline, we first applied negative controls (i.e. simulated null GWAS data) to the pipeline. The null GWAS data were created by performing GWAS and randomly assigning trait labels to a set of 381 genomes from the 1000 Genome Project (19) under normal distribution at 10 times. We performed negative spearman’s rank correlation analysis using the 10 null GWAS data and evaluated the rank-based median values of the distributions of the P-values from the correlation analysis, which were sorted in ascending order. An averaged quantile–quantile (Q–Q) plot of the results of the 10 null GWAS showed that the output P-values followed uniformly distributed null distributions, confirming robust controls of the false-positive rates (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2). These results demonstrated the statistical robustness of our method (i.e. strict control of false-positive rates).

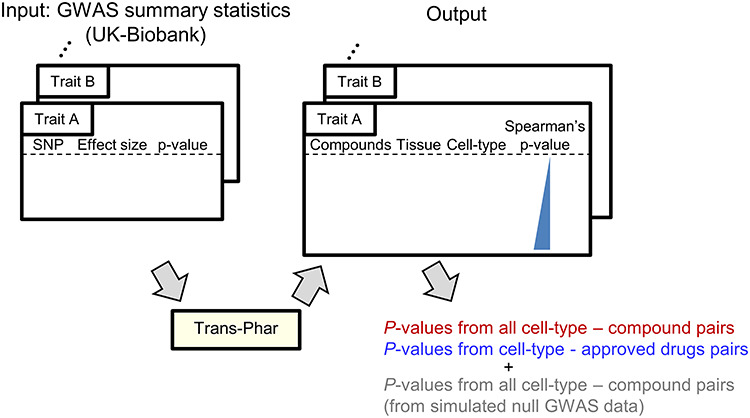

Next, to validate whether true-positive drug–disease relationships (which means the detection of the approved drug for the inputted disease itself) are statistically enriched in a broad range of human traits and diseases, we applied the UK-Biobank GWAS summary statistics, which have contained a quite broad range of diseases and traits (17,18), to the pipeline. Using UK-Biobank GWAS summary statistics, we examined whether approved drugs for the disease of inputted GWAS were detected with statistical significance by the following method (Fig. 2). We first collected the GWAS summary statistics: (1) whose single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based heritability calculated by the linkage disequilibrium score regression (LDSC) (20,21) were >0.001 and (2) which had genome-wide significant variants (P < 5.0 × 10−8). Of these, we further selected the 30 disease GWAS summary statistics in descending order of the number of the curated approved drugs from the ChEMBL database (22) and the Therapeutic Target Database (TTD) (23). The selected 30 GWAS diseases consisted of six major disease categories (certain infectious and parasitic diseases, neoplasms, mental and behavioral disorders, diseases of the circulatory system, diseases of the respiratory system and diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue; Supplementary Material, Table S1).

Figure 2.

Empirical evaluation of our pipeline using the UK-Biobank GWAS summary statistics. The 30 UK-Biobank GWAS summary statistics were selected for the evaluation of our pipeline (see the detailed definitions in Materials and Methods). As outputs, negative Spearman’s rank correlation analysis P-values, each of which corresponds to the correlation P-value between the TWAS top genes in a GTEx tissue and a compound-perturbed gene expression change in a specific cell-type, were obtained. Also, P-values corresponding to all pairs of TWAS and approved drug-perturbed gene expression data were obtained.

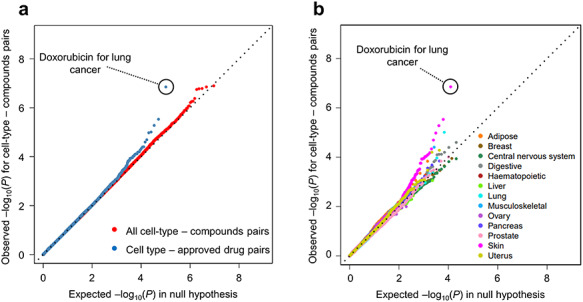

We applied our Trans-Phar pipeline to these 30 GWAS summary statistics to obtain a total of 9 266 160 P-values from all cell-type-compound pairs (308 872 P-values per each inputted GWAS summary statistics) and a total of 102 348 P-values from all cell-type-approved drug pairs. Then, we visually assessed the distributions of these GWAS-TWAS-library linkage P-values (Fig. 3A). The Q–Q plots of the P-values for all the disease, cell-type and drug pairs followed those under the null hypothesis. However, the Q–Q plots of the P-values corresponding to the disease and approved drug pairs showed a significant inflation of the test statistics in its tail. The top-associated disease and approved drug pairs was lung cancer [malignant neoplasm of bronchus and lung; International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) code = C34] and DNA intercalator of doxorubicin (P = 1.4 × 10−7; FDR-q = 0.014; Table 1) under cell-type specificity of skin (GTEx) and malignant melanoma cells of A375 (CMap L1000 library). The top cell-type-approved drug pairs detected by Trans-Phar are shown in Table 1. In addition, we also applied our pipeline by using phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trial drugs, as the same method for the approved drugs to obtain P-values from all cell-type-phase 1 clinical trial drug pairs or all cell-type-phase 2 clinical drug pairs. Q–Q plot for P-values corresponding to the diseases and phase 1 or phase 2 clinical drug pairs (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3) showed that phase 1 and phase 2 clinical drug pairs had still inflation of the test statistics in their tails, but their inflations were relatively smaller than that of the approved drugs. The top-ranked phase 1 clinical drugs were foretinib for lung cancer (ICD-10 code = C34) and dasatinib for melanoma and other malignant neoplasms of skin (ICD-10 code = C43-C44). The top-ranked phase 2 clinical drug was AZD-2014 for lung cancer (ICD-10 code = C34).

Figure 3.

Q–Q plots for the 30 UK-Biobank GWAS summary statistics. Q–Q plots for the 30 UK-Biobank GWAS summary statistics for all tissue- or/and cell-type categories (A) and per 13 tissue- or/and cell-type category (B). The x-axis reflects an estimated distribution of P-values under the null hypothesis. The y-axis in (A) reflects an observed distribution of P-values for all cell-type-compound pairs (red) and cell-type-approved drug compound pairs (blue) from the 30 UK-Biobank GWAS summary statistics. The y-axis in (B) reflects P-values for cell-type-approved drug compound pairs in each tissue- or/and cell-type category from the 30 UK-Biobank GWAS summary statistics.

Table 1.

Top signals from all cell-type-approved drug pairs screened from the 30 disease GWAS summary statistics from UK-Biobank

| Inputted GWAS summary statistics (source: GeneATLAS) | ICD-10 code | GTEx tissue | CMap L1000 library cell-type | CMap L1000 library compound (dose, h) | Mechanistic action of compound | P | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malignant neoplasm of bronchus and lung | C34 | Skin not sun-exposed | A375 | Doxorubicin (0.12 μM, 24 h) | DNA intercalator | 1.4 × 10−7 | 0.0144 |

| Malignant neoplasm of bronchus and lung | C34 | Skin not sun-exposed | A375 | Epirubicin (0.37 μm, 24 h) | TOP2 inhibitor | 2.9 × 10−6 | 0.150 |

| Malignant neoplasm of bronchus and lung | C34 | Skin not sun-exposed | A375 | Epirubicin (0.12 μm, 24 h) | TOP2 inhibitor | 5.3 × 10−6 | 0.180 |

| Other forms of heart disease | I30-I52 | Lung | HCC515 | Quinidine (10 μM, 24 h) | SCN5A inhibitor | 9.8 × 10−6 | 0.215 |

| Malignant neoplasm of bronchus and lung | C34 | Skin not sun-exposed | A375 | Epirubicin (0.04 μm, 24 h) | TOP2 inhibitor | 1.1 × 10−5 | 0.215 |

SCN5A, sodium channel α5 subunit; TOP2, topoisomerase II. The therapeutic targets with FDR-q < 0.25 are listed.

Next, to evaluate the approved drug pairs from the viewpoint of tissue- or/and cell-type specificity, we evaluated these approved drug pairs in each of the 13 tissue- or/and cell-type categories defined in Supplementary Material, Figure S1. The Q–Q plots of P-values which were separated into 13 tissue- or/and cell-type categories showed more significant inflation than that of P-values from all the cell-type-approved drug pairs, especially in skin category (Fig. 3B). In the skin category, 15 significantly associated disease and approved drug pairs (FDR-q < 0.1) were found (Supplementary Material, Table S2). These pairs contained lung cancer (ICD-10 code = C34) with approved anti-cancer drugs and other rheumatoid arthritis (ICD-10 code = M06) with approved anti-rheumatoid arthritis drugs. Most of the top signals from the skin cell-type-approved drug pairs contained lung cancer (ICD-10 code = C34) with approved anti-cancer drugs (doxorubicin, epirubicin and mitoxantrone) under cell-type specificity of A375 (malignant melanoma cells with epithelial-like morphology). Although most top signals from the lung cancer GWAS had a specificity of A375, characteristics of these signals may reflect the pathophysiology of lung cancer (epithelial cells in lung are related to the arise of lung cancer). Considering these results, our pipeline could successfully detect already approved drugs with higher sensitivity in specific tissue- or/and cell-type categories than all categories, from the inputted disease GWAS summary statistics.

Application of the integration pipeline to European GWAS meta-analysis summary statistics

Motivated by the empirical robustness and statistical power of our Trans-Phar pipeline, we then expanded the target GWAS from the UK-Biobank GWAS summary statistics into the large-scale European GWAS meta-analysis summary statistics to further detect compounds that could be promising novel therapeutic targets. We collected a total of 17 large-scale European GWAS meta-analysis summary statistics, which consisted of three major categories (immune/allergy, metabolic/cardiovascular and neuropsychiatric; Table 2). These GWASs had sufficient numbers of significant disease-related loci with relatively large estimates on the SNP-based heritability calculated by LDSC (>0.01). We also adopted the latest COVID-19 GWAS meta-analysis results released by the COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative (ANA_B2_V2 as hospitalized COVID vs. population, which was the largest-scale meta-analysis released from the consortium on July 2, 2020).

Table 2.

GWAS meta-analysis summary statistics used for in silico potential drug candidates

| Inputted disease/trait GWAS summary statistics | Disease/trait category | No. of samples (cases, controls) | Reference PubMed ID |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) | Neuropsychiatric | (20 806, 59 804) | 31178821 |

| Asthma (adult-onset) | Immune/allergy | (26 582, 300 671) | 30929738 |

| Asthma (child-onset) | Immune/allergy | (13 962, 300 671) | 30929738 |

| Atopy | Immune/allergy | (18 900, 84 166) | 26482879 |

| Body mass index | Metabolic/cardiovascular | 344 069 | 25673413 |

| Coronary artery disease | Metabolic/cardiovascular | (57 347, 219 521) | 28714975 |

| Celiac disease | Immune/allergy | (4533, 10 750) | 20190752 |

| Crohn’s disease | Immune/allergy | (12 194, 28 072) | 28067908 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | Metabolic/cardiovascular | 361 141 | 31427789 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | Metabolic/cardiovascular | (48 286, 250 671) | 29632382 |

| Multiple sclerosis | Neuropsychiatric | (14 802, 26 703) | 31604244 |

| Parkinson’s disease | Neuropsychiatric | (33 674, 449 056) | 31701892 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Immune/allergy | (14 361, 42 923) | 24390342 |

| Systolic blood pressure (SBP) | Metabolic/cardiovascular | 361 402 | 31427789 |

| Schizophrenia | Neuropsychiatric | (40 675, 64 643) | 29483656 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Immune/allergy | (6748, 11 516) | 28714469 |

| Ulcerative colitis | Immune/allergy | (12 366, 33 609) | 28067908 |

| COVID-19 (hospitalized cases vs. controls; ANA_B2_V2) | — | (3199, 897 488) | — |

We applied our Trans-Phar pipeline to these GWAS meta-analysis summary statistics and obtained 308 872 P-values from all the cell-type-compound pairs per each inputted GWAS summary statistics. As a result, we obtained sets of cell-type-compound pairs in a specific tissue- or/and cell-type category with reverse expression correlation. We highlighted the top 14 cell-type-compound pairs from seven diseases/traits in Table 3 (BH-adjusted FDR-q < 0.25). Further, 55 cell-type-compound pairs from nine diseases/traits are also shown in Supplementary Material, Table S3 (BH-adjusted FDR-q < 0.50).

Table 3.

Top signals from all cell-type-compound pairs screened from the large-scale European GWAS meta-analysis summary statistics

| Inputted GWAS summary statistics | GTEx tissue | CMap L1000 library cell-type | CMap L1000 library compound (dose, h, #no. of replicates) | Mechanistic action of compound | P | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia | Brain hypothalamus | NEU | Anisomycin (10 μM, 24 h) | Protein synthesis inhibitor | 1.8 × 10−7 | 0.056 |

| COVID−19 (hospitalized) | Cells EBV-transformed lymphocytes | WSUDLCL2 | Verapamil (10 μM, 6 h) | Ca2+ channel blocker | 2.2 × 10−7 | 0.068 |

| Asthma (adult-onset) | Adipose subcutaneous | ASC | Azacitidine (10 μm, 24 h) | DNMT inhibitor | 3.7 × 10−7 | 0.114 |

| SBP | Lung | A549 | BRD-K05645536 (5 μM, 24 h) | — | 4.6 × 10−7 | 0.116 |

| SBP | Skin not sun-exposed suprapubic | A375 | NSC 119889 (10 μM, 6 h) | Protein synthesis inhibitor | 7.5 × 10−7 | 0.116 |

| Schizophrenia | Brain hypothalamus | NPC | Proscillaridin (10 μM, 24 h) | Na+/K+-ATPase inhibitor | 8.9 × 10−7 | 0.138 |

| Schizophrenia | Brain hypothalamus | NPC | Digoxin (10 μM, 24 h, 1) | Na+/K+-ATPase inhibitor | 1.3 × 10−6 | 0.138 |

| ALS | Prostate | PC3 | BRD-K70345064 (10 μM, 24 h) | — | 8.1 × 10−7 | 0.152 |

| ALS | Prostate | PC3 | Sarsagenin (1.6 μm, 24 h) | Nuclear factor-κB inhibitor | 9.9 × 10−7 | 0.152 |

| Schizophrenia | Whole blood | JURKAT | Ibrutinib (10 μm, 24 h) | BTK inhibitor | 2.3 × 10−6 | 0.161 |

| Schizophrenia | Brain hippocampus | NPC | Digoxin (10 μM, 24 h) | Na+/K+-ATPase inhibitor | 2.6 × 10−6 | 0.161 |

| Atopy | Muscle skeletal | SKL | Pyrazolanthrone (1.11 μm, 24 h) | JNK inhibitor | 6.1 × 10−7 | 0.190 |

| Asthma (adult-onset) | Adipose subcutaneous | ASC | SB 203580 (10 μm, 24 h) | p38 MAPK inhibitor | 1.3 × 10−6 | 0.204 |

| ALS | Small intestine terminal ileum | HT29 | BRD-A13346522 (10 μM, 6 h, 1) | — | 2.4 × 10−6 | 0.247 |

BTK, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase. The therapeutic targets with FDR-q < 0.25 are listed..

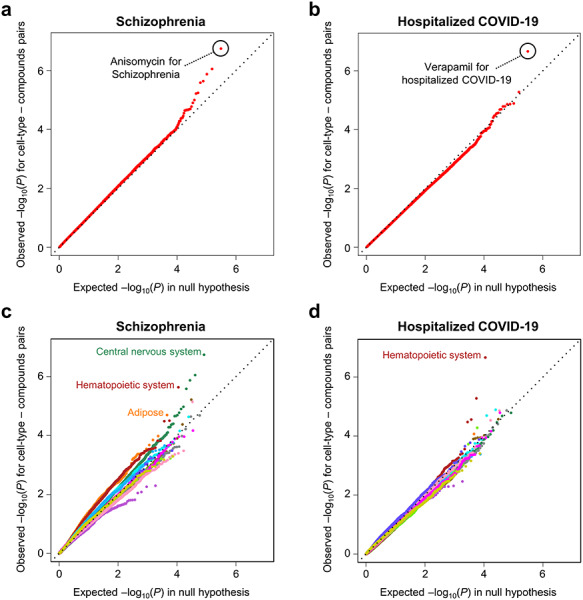

Especially, we found two strong GWAS-TWAS-compound linkages: (1) anisomycin relevance to the GREx at the brain (brain hypothalamus as the GTEx tissue and NEU cell-type as the CMap L1000 library) from schizophrenia (P = 1.8 × 10−7; FDR-q = 0.056; Fig. 4A) and (2) verapamil relevance to the GREx at lymphocytes (cells EBV-transformed lymphocytes as the GTEx tissue and WSUDLCL2 cell-type as the CMap L1000 library) from hospitalized COVID-19 (P = 1.7 × 10−7; FDR-q = 0.068; Fig. 4B). In addition, the Q–Q plots of P-values which were separated into 13 tissue/cell-type categories showed more significant inflation than that of P-values from all the cell-type-approved drug pairs, especially in the central nervous system category from schizophrenia (Fig. 4C) and in the hematopoietic tissue category from COVID-19 hospitalization (Fig. 4D). For schizophrenia, anisomycin (protein synthesis inhibitor), proscillaridin (Na+/K+-ATPase inhibitor) and digoxin (Na+/K+-ATPase inhibitor) were significantly detected (Supplementary Material, Table S4). For COVID-19 hospitalization, verapamil (Ca2+ channel blocker), 7-nitroindazole (NOS inhibitor), orantinib (PDGFR inhibitor) and enzalutamide (androgen receptor inhibitor) were significantly detected (Supplementary Material, Table S5). These results highlighted that disease-relevant tissue or cell-type categories were more likely to show apparent inflation than other tissue- or cell-type categories.

Figure 4.

Q–Q plots for European GWAS meta-analysis summary statistics with strong GWAS-TWAS-compound linkages. The x-axis reflects an estimated distribution of P-values under the null hypothesis. The y-axis reflects an observed distribution of P-values for all cell-type-compound pairs from the European GWAS meta-analysis summary statistics for (A) schizophrenia, (B) COVID-19 hospitalization and observed distribution of P-values per 13 tissue- or/and cell-type category from the European GWAS meta-analysis summary statistics for (C) schizophrenia and (D) COVID-19 hospitalization.

As the top-ranked drug we found for schizophrenia, anisomycin was reported to protect cortical neurons from hypoxia-induced neuronal death in vitro (24) and to attenuate posttraumatic stress response in animal models (25). As the top-ranked drug we found for COVID-19, verapamil is a Ca2+ channel blocker and has been approved for hypertension. Ca2+ channel blockers, including verapamil, have shown antiviral activity (26). A randomized clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of verapamil on COVID-19-hospitalized patients by the independent groups is underway by the independent groups (NCT no. NCT04351763). Although further functional and clinical assessments are warranted, our study suggested verapamil as one of the potential drug candidates for COVID-19.

Also, among the detected cell-type-compound pairs, we found compounds already approved for several diseases. For example, azacitidine, which we found relevant to GREx at adipose as GTEx tissue and adipose stem cells (ASCs) as CMap L1000 library from adult-onset asthma, is a DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) inhibitor and has been approved for myelodysplastic syndrome. ASCs are the mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) population found in adipose tissue and have been shown to down-regulate the production of various inflammatory mediators and to have the potential to be a treatment for asthma and allergic airway disease (27–29). The effects of azacitidine on ASCs were reported to reverse the age-related deterioration of adult MSCs (30). Therefore, azacitidine might be related to the therapeutic intervention for asthma by ASCs. We also found several cardiac glycosides (proscillaridin, digoxin and digitoxin) relevant to GREx at the central nervous system (brain hypothalamus/hippocampus as the GTEx tissue and NPC cell-type as CMap L1000 library) from schizophrenia. Cardiac glycosides, which bind Na+, K+ pump as ion transport modulator, might be concordant with the results of GWAS performed so far for schizophrenia (31–33), because schizophrenia-associated loci from these results contain several ion channel-encoding genes. Ion transport modulation by Na+/K+-ATPase in neurons has been reported to affect depressive disorders through neuronal activity, neurotransmission and so on (34). In summary, in silico screening by our Trans-Phar pipeline successfully identified promising drug target candidates as well as the confirmation of approved drug and clinical indication linkages, with implications on cell-type-specific pathophysiology of the diseases.

Discussion

The integration of a broad range of human phenotypes and large-scale compound databases should enhance in silico pharmacology for drug discovery and repositioning. In this study, our integration pipeline, named Trans-Phar, incorporated a functional genomics approach by TWAS from a broad range of diseases or traits and large-scale compound perturbation databases with gene expression levels. Our pipeline showed statistical robustness using simulated null GWAS data and demonstrated that it could detect both true-positive drug–disease relationships and potential drug candidates for inputted disease or trait GWAS summary statistics.

Our approach highlights several advantages. First, this approach is hypothesis-free, which is less dependent on any prior biological or chemical knowledge, such as known drug–disease relationships. This feature should be effective especially when searching drug candidates for diseases with unknown etiology, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, we expanded coverages of tissue- or/and cell-type specificity evaluated through TWAS to comprehensively obtain GREx using eQTL data from 29 GTEx tissues. Also, we used a broad compound database of CMap L1000 library, which has been updated and extended in the last few years, containing transcriptomic profiles of dozens of cultivated cell lines treated with tens of thousands of compounds. These extensions enable a comprehensive approach to detect various bioactive compounds in a broad range of tissue- or/and cell-type categories. Third, our approach was computationally simple and only requested publicly available data, such as GWAS summary statistics and compound-perturbed gene expression data. It is easy for users to refine the pipeline to include additional resources, such as in-house disease-related gene expression data and compound libraries. These advantages should accelerate finding novel drugs or therapeutic targets under different mechanisms for a broad range of diseases and a broad category of organs. Our approach would also be useful for the diseases with few known treatments or for the urgent need for drug development such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

There are a few limitations to our approach. First, the hypothesis of finding compounds using opposite expression changes from the disease tissue may not be completely true for every compound–disease pair. In some case, the expression changes identified may not be relevant for reversal because most GWAS is about the factors in development of disease rather than progression or treatment. Second, we may not find drugs whose expression changes are not strongly related to GREx, such as environmental factors. Third, the therapeutic efficacy of a compound in vivo is assumed to be more complex than the in silico matching of expression profiles concerning the tissue distribution of compounds and their effect on other organs and so on. For example, because CMap L1000 library data contain limited time point and limited dose of exposure of compounds, these expression changes could potentially be not ideal for long-term treatment for chronic diseases. From these limitations, although our pipeline can highlight and prioritize compounds efficient for diseases or traits, the in vivo validation of these compounds, such as animal models of diseases, would provide further utilization of identified compounds and insights for the therapeutic approach. In addition, our pipeline did not include consideration for the in vivo safety of compounds, therefore the hit compounds in our pipeline would be examined for the mechanism of action of compounds, or assessed in vivo whether the compounds were valuable for drug repositioning from the viewpoint of both efficacy and safety of the compounds.

In conclusion, we have developed a framework for detecting potential drug or drug target candidates for disease susceptibility. Our study demonstrated that the Trans-Phar pipeline could find novel drug–disease relationships in tissue- or/and cell-type specific manners. Our framework would be useful for therapeutic approaches, such as drug development and drug repositioning to a broad range of complex diseases or traits.

Materials and Methods

Framework of GWAS-TWAS-compound library integration pipeline software

TWAS was performed using the FOCUS software (35) for each of the GWAS summary statistics. The European 1000 Genomes version 3 LD panel was used for TWAS. We chose 44 GTEx version 7 eQTL data whose sample size was >100 as an eQTL expression panel for TWAS. We obtained the predicted gene expression level in each tissue. After conducting TWAS, the top-ranked genes (top decile in the absolute value of the TWAS Z-score) were used in the following correlation analyses.

We used LINCS CMap L1000 library data (phases I and II) as compound library data (16). Level 5 data (moderated Z-scores from each perturbagen treatment on each cell) were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus database, whose accession numbers were GSE92742 and GSE70138, respectively. In these data, we chose compound-perturbed gene expression data, which consist of 83 cell types and 20 547 compounds. For each compound-perturbed gene expression data, we defined significant DEGs using gene expression change data (Z-score) with cutoff BH-adjusted FDR-q < 0.01 and then excluded data whose significant DEGs were lower than 5. Then, we defined 13 tissue- or/and cell-type categories (adipose, breast, central nervous system, digestive, hematopoietic system, liver, lung, musculoskeletal system, ovary, pancreas, prostate, skin and uterus) and assigned 29 GTEx tissues and 77 LINCS CMap L1000 library cell types to 13 categories (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1). Then, we performed negative Spearman’s rank correlation analysis of all the pairs of top-ranked genes derived from each tissue GREx and each compound-perturbed gene expression data within the same tissue- or/and cell-type category. Finally, we obtained a total of 308 872 P-values corresponding to each of the correlation analyses as described before.

We developed this pipeline as publicly available software named Trans-Phar (in https://github.com/konumat/Trans-Phar). This pipeline software needs the formatted GWAS summary statistics as the input data and then outputs P-values and BH-adjusted FDR-q corresponding to each set of the TWAS tissue-CMap L1000 library cell-type-compound pairs (at a specific dose and at a specific time point).

Empirical evaluation of the statistical robustness of the pipeline using null GWAS data

To empirically evaluate the statistical robustness of our pipeline, we tested our pipeline using 10 simulated null GWAS data, as negative-control GWAS summary statistics, which were created as described later. We obtained a total of 10 patterns of cell-type-compound P-value distributions, each of which contained 308 872 P-values. We used the distribution of the median of each P-value, which was sorted in the ascending order, as negative-control P-value distribution. We also visually compared negative-control P-value distribution to the null hypothesis using a Q–Q plot.

True-positive drug–disease relationship evaluation using the UK-Biobank GWAS summary statistics

To validate whether true-positive drug–disease relationships (which means the detection of the already approved drugs for the treatment of the inputted diseases themselves) can be detected in a broad range of human traits and diseases, we applied 30 UK-Biobank GWAS summary statistics to our pipeline. The criteria for the selection of the 30 UK-Biobank GWAS summary statistics were as follows: (1) diseases with comparatively high SNP-based heritability in the GWAS and (2) diseases enriched with curated already approved drugs corresponding to each disease itself, as described later. We assessed negative Spearman’s rank correlation analysis of the pairs of the top-ranked genes derived from each tissue GREx and approved drug-perturbed gene expression data in addition to all the pairs of the top-ranked genes derived from each tissue’s GREx and each compound-perturbed gene expression data. We evaluated these 30 GWAS summary statistics to obtain a total of 9 266 160 P-values from all cell-type-all compound pairs (308 872 P-values per each inputted GWAS summary statistics) and 102 348 P-values from all cell-type-approved drug pairs. We compared the distribution of these P-values under the null hypothesis. BH-adjusted FDR-q values were calculated for the correction for multiple testing of correlation analysis [multiple testing means all tests for all cell-type-all compound pairs or all tests for all cell-type-certain drug category (i.e. already approved drugs, phase 1 clinical trial drugs, and phase 2 clinical trial drugs) pairs].

To validate specificity of tissue- or/and cell-type categories in 102 348 P-values from all cell-type-approved drug pairs described before, we separated 102 348 P-values to 13 tissue- or/and cell-type categories defined in Supplementary Material, Figure S1. Then, we also compared the distribution of these P-values under the null hypothesis. BH-adjusted FDR-q values were calculated for the correction for multiple testing of correlation analysis within each tissue or cell-type categories.

Application of the integration pipeline using European GWAS meta-analysis summary statistics

To evaluate the integration pipeline to find potential drug candidates effective for inputted GWAS summary statistics, we chose 17 European GWAS meta-analysis summary statistics from three disease/trait categories, as described later. We obtained 308 872 P-values from all pairs of top-ranked genes derived from each tissue GREx and each compound-perturbed gene expression data per inputted GWAS summary statistics. We also obtained P-values of each 13 tissue- or/and cell-type category by separating 308 872 P-values into these categories. Then, we calculated the BH-adjusted FDR-q for the correction for multiple testing of correlation analysis.

Collection of the GWAS summary statistics datasets

To evaluate true-positive drug–disease relationship enrichment in a broad range of human traits and diseases, we collected the UK-Biobank GWAS summary statistics from the GeneATLAS database (nPhenotype = 778) (18). For the 778 GWAS summary statistics, we applied the following exclusion criteria: (1) not disease phenotypes with ICD-10 diagnostic codes, (2) SNP-based heritability calculated by LDSC (20,21) was <0.001 and (3) there exist no genome-wide significant variants (P < 5.0 × 10−8). After exclusion, we chose the top 30 UK-Biobank GWAS summary statistics in descending order of the number of curated approved drugs corresponding to each disease GWAS obtained from the ChEMBL database (22) and TTD (23). These 30 UK-Biobank GWAS summary statistics consisted of six major disease categories [certain infectious and parasitic diseases (n = 5), neoplasms (n = 13), mental and behavioral disorders (n = 2), diseases of the circulatory system (n = 5), diseases of the respiratory system (n = 1) and diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue (n = 4); Supplementary Material, Table S1].

To detect potential drug candidates with enhanced statistical power, we then used the large-scale European GWAS meta-analysis summary statistics. We curated 17 European GWAS meta-analysis summary statistics for which a large number of significant disease-related loci were reported and whose SNP-based heritability was >0.01. These 17 European GWAS meta-analysis summary statistics consist of three major categories [immune/allergy (n = 8), metabolic/cardiovascular (n = 5) and neuropsychiatric (n = 4)]. Also, we adopted the COVID-19 meta-analysis GWAS summary statistics for which urgent drug-repositioning strategy has been needed. COVID-19 GWAS meta-analysis round 3 data (ANA_B2_V2 as hospitalized COVID vs. population) were downloaded from the COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative (July 2, 2020 release). All the GWAS summary statistics used for the detection of potential drug candidates are shown in Table 2.

Simulated GWAS summary statistics (null GWAS data as negative-control)

As the negative-control input data for our pipeline, we created randomized dummy trait GWAS datasets by randomly assigning trait labels to a set of 381 European human genomes from the 1000 Genome Project (19) under the assumption of following a normal distribution (average = 100; standard deviation = 20). GWAS on the randomized trait data were performed using the linear regression analysis method implemented in PLINK2 (36). We performed GWAS using randomized trait data with repetition of trait randomization at 10 times and then obtained a total of 10 randomized trait GWAS summary statistics as negative controls.

Collection and curation of approved drugs

We collected the compound information on current, or previously developed, clinical indications from the ChEMBL database version 25 (22) and TTD version 6.1.01 (23). To curate linkages between the diseases and the approved drugs, we used the ICD-10 diagnostic codes as disease ontology terms. For the ChEMBL database, in which drug indications are annotated using Experimental Factor Ontology (EFO) terms, we converted the EFO terms to ICD-10 diagnostic codes using the EMBL-EBI ontology database. Then, we extracted a list of diseases with ICD-10 diagnostic codes and defined approved drugs, phase 1 clinical trial drugs and phase 2 clinical trial drugs for each ICD-10 diagnostic code, which were curated in either ChEMBL or TTD.

URLs

Trans-Phar, https://github.com/konumat/Trans-Phar

GTEx, https://www.gtexportal.org/home/

CMap L1000 library, https://clue.io/

GeneATLAS, http://geneatlas.roslin.ed.ac.uk

The COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative, https://www.covid19hg.org/

ChEMBL database, https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/

TTD database, http://db.idrblab.net/ttd/

Data availability

All the data used for this analysis were obtained from the public databases as indicated in URLs.

Code availability

Python/R/Shell scripts for the Trans-Phar pipeline are available at Trans-Phar GitHub repository (https://github.com/konumat/Trans-Phar).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the members of the COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative for kindly releasing the GWAS summary statistics. This study was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (19H01021 and 20K21834) and Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (JP20km0405211, JP20ek0109413, JP20ek0410075, JP20gm4010006, JP20km0405217, JP20fk0108265), Takeda Science Foundation and Bioinformatics Initiative of Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka University. T.K. is an employee of JAPAN TOBACCO INC.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

Contributor Information

Takahiro Konuma, Department of Statistical Genetics, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Suita 565-0871, Japan; Central Pharmaceutical Research Institute, JAPAN TOBACCO INC., Takatsuki 569-1125, Japan.

Kotaro Ogawa, Department of Statistical Genetics, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Suita 565-0871, Japan; Department of Neurology, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Suita 565-0871, Japan.

Yukinori Okada, Department of Statistical Genetics, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Suita 565-0871, Japan; Laboratory of Statistical Immunology, Immunology Frontier Research Center (WPI-IFReC), Osaka University, Suita 565-0871, Japan; Integrated Frontier Research for Medical Science Division, Institute for Open and Transdisciplinary Research Initiatives, Osaka University, Suita 565-0871, Japan.

Author’s contributions

T.K. and Y.O. designed the study and wrote the manuscript. T.K. implemented the Trans-Phar pipeline and conducted the analysis. T.K. and K.O. collected the data.

References

- 1). Visscher, P.M., Wray, N.R., Zhang, Q., Sklar, P., McCarthy, M.I., Brown, M.A. and Yang, J. (2017) 10 years of GWAS discovery: biology, function, and translation. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 101, 5–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Nelson, M.R., Tipney, H., Painter, J.L., Shen, J., Nicoletti, P., Shen, Y., Floratos, A., Sham, P.C., Li, M.J., Wang, J.et al. (2015) The support of human genetic evidence for approved drug indications. Nat. Genet., 47, 856–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). King, E.A., Davis, J.W. and Degner, J.F. (2019) Are drug targets with genetic support twice as likely to be approved? Revised estimates of the impact of genetic support for drug mechanisms on the probability of drug approval. PLoS Genet., 15, e1008489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Okada, Y., Wu, D., Trynka, G., Raj, T., Terao, C., Ikari, K., Kochi, Y., Ohmura, K., Suzuki, A., Yoshida, S.et al. (2014) Genetics of rheumatoid arthritis contributes to biology and drug discovery. Nature, 506, 376–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Sakaue, S. and Okada, Y. (2019) GREP: genome for REPositioning drugs. Bioinformatics, 35, 3821–3823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Fang, H., The ULTRA-DD Consortium, Hans, D.W., Knezevic, B., Burnham, K.L., Osgood, J., Sanniti, A., Lara, A.L., Kasela, S., Cesco, S.D.et al. (2019) A genetics-led approach defines the drug target landscape of 30 immune-related traits. Nat. Genet., 51, 1082–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Farh, K.K., Marson, A., Zhu, J., Kleinewietfeld, M., Housley, W.J., Beik, S., Shoresh, N., Whitton, H., Ryan, R.J.H., Shishkin, A.A.et al. (2015) Genetic and epigenetic fine mapping of causal autoimmune disease variants. Nature, 518, 337–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Boyle, E.A., Li, Y.I. and Pritchard, J.K. (2017) An expanded view of complex traits: from polygenic to Omnigenic. Cell, 169, 1177–1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Cano-Gamez, E. and Trynka, G. (2020) From GWAS to function: using functional genomics to identify the mechanisms underlying complex diseases. Front. Genet., 11, 424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). GTEx Consortium (2017) Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature, 550, 204–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Wainberg, M., Sinnott-Armstrong, N., Mancuso, N., Barbeira, A.N., Knowles, D.A., Golan, D., Ermel, R., Ruusalepp, A., Quertermous, T., Hao, K.et al. (2019) Opportunities and challenges for transcriptome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet., 51, 592–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Gusev, A., Ko, A., Shi, H., Bhatia, G., Chung, W., Phenninx, B.W., Jansen, R., De Geus, E.J., Boomsma, D.I., Wright, F.A.et al. (2018) Integrative approaches for large-scale transcriptome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet., 48, 245–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Gusev, A., Mancuso, N., Won, H., Kousi, M., Finucane, H.K., Reshef, Y., Song, L., Safi, A., Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, McCarroll, S.et al. (2018) Transcriptome-wide association study of schizophrenia and chromatin activity yields mechanistic disease insights. Nat. Genet., 50, 538–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). Mancuso, N., Shi, H., Goddard, P., Kichaev, G., Gusev, A. and Pasaniuc, B. (2017) Integrating gene expression with summary association statistics to identify genes associated with 30 complex traits. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 100, 473–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Sirota, M., Dudley, J.T., Kim, J., Chiang, A.P., Morgan, A.A., Sweet-Cordero, A., Sage, J. and Butte, A.J. (2011) Discovery and preclinical validation of drug indications using compendia of public gene expression data. Sci. Transl. Med., 3, 96ra77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16). Subramanian, A., Narayan, R., Corsello, S.M., Peck, D.D., Natoli, T.E., Lu, X., Gould, J., Davis, J.F., Tubelli, A.A., Asiedu, J.K.et al. (2017) A next generation connectivity map: L1000 platform and the first 1,000,000 profiles. Cell, 171, 1437–1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). Bycroft, C., Freeman, C., Petkova, D., Band, G., Elliott, L.T., Sharp, K., Motyer, A., Vukcevic, D., Delaneau, O., O’Connell, J.et al. (2018) The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature, 562, 203–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). Canela-Xandri, O., Rawlik, K. and Tenesa, A. (2018) An atlas of genetic associations in UK Biobank. Nat. Genet., 50, 1593–1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). 1000 Genomes Project Consortium (2015) A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature, 526, 68–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Bulik-Sullivan, B., Finucane, H.K., Anttila, V., Gusev, A., Day, F.R., Loh, P., Repro Gen Consortium, Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, Genetic Consortium for Anorexia Nervosa of the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 3, Duncan, L.et al. (2015) An atlas of genetic correlations across human diseases and traits. Nat. Genet., 47, 1236–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21). Bulik-Sullivan, B.K., Loh, P., Finucane, H.K., Ripke, S., Yang, J., Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, Patterson, N., Daly, M.J., Price, A.L. and Neale, B.M. (2015) LD score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet., 47, 291–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22). Gaulton, A., Hersey, A., Nowotka, M., Bento, A.P., Chambers, J., Mendez, D., Mutowo, P., Atkinson, F., Bellis, L.J., Cibrián-Uhalte, E.et al. (2017) The ChEMBL database in 2017. Nucleic Acids Res., 45, D945–D954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Wang, Y., Zhang, S., Li, F., Zhou, Y., Zhang, Y., Wang, Z., Zhang, R., Zhu, J., Ren, Y., Tan, Y.et al. (2020) Therapeutic target database 2020: enriched resource for facilitating research and early development of targeted therapeutics. Nucleic Acids Res., 48, D1031–D1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). Cohen, H., Kaplan, Z., Matar, M.A., Loewenthal, U., Kozlovsky, N. and Zohar, J. (2006) Anisomycin, a protein synthesis inhibitor, disrupts traumatic memory consolidation and attenuates posttraumatic stress response in rats. Biol. Phychiatry, 60, 767–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25). Hong, S., Qian, H., Zhao, P., Bazzy-Asaad, A. and Xia, Y. (2007) Anisomycin protects cortical neurons from prolonged hypoxia with differential regulation of p38 and ERK. Brain Res., 1149, 76–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26). Salata, C., Calistri, A., Parolin, C., Baritussio, A. and Palù, G. (2017) Antiviral activity of cationic amphiphilic drugs. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther., 15, 483–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27). Gonzalez-Rey, E., Anderson, P., González, M.A., Rico, L., Büscher, D. and Deigado, M. (2009) Human adult stem cells derived from adipose tissue protect against experimental colitis and sepsis. Gut, 58, 929–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28). Nejad-Moghaddam, A., Panahi, Y., Alitappeh, M.A., Borna, H., Sholrgozar, M.A. and Ghanei, M. (2015) Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of airway remodeling in pulmonary diseases. Iran. J. Allergy Asthma Immunol., 14, 552–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29). Castro, L.L., Kitoko, J.Z., Xisto, D.G., Olsen, P.C., Guedes, H.L.M., Morales, M.M., Lopes-Pacheco, M., Cruz, F.F. and Rocco, P.R.M. (2020) Multiple doses of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal cells induce immunosuppression in experimental asthma. Stem Cells Transl. Med., 9, 250–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30). Kornicka, K., Marycz, K., Marędziak, M., Tomaszewski, K.A. and Nicpoń, J. (2017) The effects of the DNA methyltranfserases inhibitor 5-azacitidine on ageing, oxidative stress and DNA methylation of adipose derived stem cells. J. Cell. Mol. Med., 21, 387–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31). Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (2014) Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature, 511, 421–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32). Pardiñas, A.F., Holmans, P., Pocklington, A.J., Escott-Price, V., Ripke, S., Carrera, N., Legge, S.E., Bishop, S., Cameron, D., Hamshere, M.L.et al. (2018) Common schizophrenia alleles are enriched in mutation-intolerant genes and in regions under strong background selection. Nat. Genet., 50, 381–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33). Pers, T.H., Timshel, P., Ripke, S., Lent, S., Sullivan, P.F., O’Donovan, M.C., Franke, L., Hirschhorn, J.N. and Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (2016) Comprehensive analysis of schizophrenia-associated loci highlights ion channel pathways and biologically plausible candidate causal genes. Hum. Mol. Genet., 25, 1247–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34). Lichtstein, D., Ilani, A., Rosen, H., Horesh, N., Singh, S.V., Buzaglo, N. and Hodes, A. (2018) Na+, K+-ATPase signaling and bipolar disorder. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 19, 2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35). Mancuso, N., Freund, M.K., Johnson, R., Shi, H., Kichaev, G., Gusev, A. and Pasaniuc, B. (2019) Probabilistic fine-mapping of transcriptome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet., 51, 675–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36). Chang, C.C., Chow, C.C., Tellier, L.C., Vattikuti, S., Purcell, S.M. and Lee, J.J. (2015) Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience, 4, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data used for this analysis were obtained from the public databases as indicated in URLs.