Abstract

Background

People with a previous diagnosis of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are more likely to develop serious forms of COVID-19 or die. Mexico is the country with the fourth highest fatality rate from SARS-Cov-2, with high mortality in younger adults.

Objectives

To describe and characterize the association of NCDs with the case-fatality rate (CFR) adjusted by age and sex in Mexican adults with a positive diagnosis for SARS-Cov-2.

Methods

We studied Mexican adults aged ≥20 years who tested positive for SARS-Cov-2 during the period from 28 February to 31 July 2020. The CFR was calculated and associations with history of NCDs (number of diseases and combinations), severity indicators and type of institution that treated the patient were explored. The relative risk (RR) of death was estimated using Poisson models and CFR was adjusted using logistic models.

Results

We analysed 406 966 SARS-Cov-2-positive adults. The CFR was 11.2% (13.7% in men and 8.4% in women). The CFR was positively associated with age and number of NCDs (p trend <0.001). The number of NCDs increased the risk of death in younger adults when they presented three or more NCDs compared with those who did not have any NCDs [RR, 46.6; 95% confidence interval (CI), 28.2, 76.9 for women; RR, 16.5; 95% CI, 9.9, 27.3 for men]. Lastly, there was great heterogeneity in the CFR by institution, from 4.6% in private institutions to 18.9% in public institutions.

Conclusion

In younger adults, higher CFRs were associated with the total number of NCDs and some combinations of type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: Hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, COVID-19, SARS-Cov-2, mortality

Key Messages

The relative risk (RR) of death increases with the number of non-communicable diseases (NCDs).

NCDs increase the RR of death differentially by age groups, with the highest RR seen in young adults.

Some combinations of NCDs are associated with greater increases in case-fatality rates (CFRs).

There is great heterogeneity in the CFR by type of healthcare institution.

Background

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 disease (COVID-19)1 can produce mild respiratory symptoms that remit naturally.2 However, in some cases, it can also evolve into acute respiratory distress syndrome, causing multiple-organ failure and death.3

As of 8 November 2020, >50.3 million people have been infected with SARS-Cov-2 worldwide and >1.254 million have died from this cause. When comparing the mortality rate per 100 000 inhabitants during this period, Mexico had the sixth highest mortality rate and had officially tested 2.568 million people, reaching 961 938 positive cases.4

People with a previous diagnosis of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as high blood pressure (HBP), type 2 diabetes (T2D), cardiovascular disease (CVD) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),5,6 as well as those who are older or male, are more likely to develop serious conditions of COVID-19 or die from this cause.7 In China, the fatality rate (number of deaths per 100 infected) for COVID-19 was 2.3%. However, it was 6.0% for people with hypertension, 7.3% for adults with diabetes and 10.5% for people with cardiovascular disease.8 On the one hand, differences were observed in the hazard ratio (HR) of people who developed severe symptoms or died, being higher in men (HR 1.6) than in women (HR 1.0) and in people ≥65 years old (HR 1.9) as opposed to those <65 years old (HR 1.0).9 Epidemiological studies have shown that the risk of mortality from SARS-Cov-2 increases 2.5 times when the patient has HBP, 1.9 times when they have diabetes10 and 7.9 times when they have CVD.11

In Mexico, the association between obesity and diabetes with a higher risk of SARS-Cov-2 infection,12 severity and need for hospitalization has been documented.13 A recent study has also documented a higher risk of complications at the beginning of hospitalization among patients with SARS-Cov-2 who also had co-morbidities like obesity, hypertension and diabetes.14

In a country like Mexico, where 49% of adults have hypertension,15 14% have diabetes16 and 24% develop CVD,17 it is important to quantify the risk of death among the population with NCDs and COVID-19. It is also important to consider the role of the health system in providing care to patients with SARS-Cov-2 in cases with and without other NCDs. Understanding the magnitude of this association and its related characteristics can improve targeted strategies that aim to identify adults who are most likely to be infected and die of SARS-Cov-2. Our objective is to describe and characterize the association between NCDs and case-fatality rates (CFRs), adjusting by factors that increase the risk of death, such as age and sex, in Mexican adults with a positive diagnosis of SARS-Cov-2.

Methods

Study design and participants

Our study population consisted of Mexican adults aged ≥20 years who tested positive for SARS-Cov-2 and were registered in the Epidemiological Surveillance System for Respiratory Diseases database (SISVER, Spanish acronym). This database includes epidemiological information at the national level, with mandatory reporting of diseases like SARS-Cov-2 for all public or private health units and laboratories. The information was obtained from the Ministry of Health’s website (https://www.gob.mx/salud/documentos/datos-abiertos-152127).18 This data set is open to the public and is continuously updated. We analysed data from the beginning of the epidemic (28 February 2020) to 31 July 2020. The database contains information on all outpatients and those hospitalized, as well as on deaths from SARS-Cov-2 in Mexico.18

Confirmation of COVID-19 cases

Adults were suspected of having COVID-19 if they reported at least two of the following symptoms within the past 7 days: fever, headache and cough, accompanied by at least one of the following signs: arthralgia, conjunctivitis, pain in the chest, dyspnea, myalgia, odynophagia or rhinorrhea. For all suspected cases, two protocols were followed: testing for SARS-Cov-2 and epidemiological surveillance.18 As authorized by the National Committee for Epidemiological Surveillance (CONAVE, Spanish acronym),18 cases were confirmed using the polymerase chain reaction test based on the Berlin protocol.19

NCD assessment

An adult was considered to have an NCD when the patient reported having been previously diagnosed with: HBP, T2D, obesity (OB), CVD, chronic kidney disease (CKD) or COPD. We selected these NCDs because they are those with the highest prevalence in Mexico and because of their association with greater severity of COVID-19.15–17 The instrument used to collect the information was an official standardized questionnaire used by the federal government’s Epidemiological Surveillance System.18 It collects: socio-demographic information (age and sex), personal pathological history (presence of NCDs, date on which the symptoms associated with the infection began and exposure to tobacco), treatment characteristics and indicators of severity such as the presence of pneumonia, need for hospitalization, assistance in the Intensive Care Unit and the use of assisted mechanical intubation (IMA). We classified information on NCDs by number, as follows: no NCDs, one NCD, two NCDs and three or more NCDs.

Institution in which healthcare was provided

We included the institution in which patients received care in the analysis. We categorized the healthcare institutions as Private, Ministry of Navy (SEMAR), Federal Ministry of Health (SS), (Red Cross+DIF+Municipal+University), Ministry of National Defense (SEDENA), not specified, State Secretaries of Health, Petroleos Mexicanos (PEMEX), Institute of Security and Social Services for State Workers (ISSSTE) and Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS).

Statistical analysis

Fatality due to SARS-Cov-2 was calculated through the CFR and expressed in percentages (number of deaths from COVID/total patients identified with COVID in the period described × 100) with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs).

The CFR was disaggregated by sex, age and NCDs. To assess trends between age groups and the number of NCDs, tests were performed using robust estimates by Bootstrap. The relative risk (RR) was estimated using Poisson models and the probability of death (CFR adjusted) using logistic regression, which in both cases were adjusted in the models for age, sex, the presence of pre-existing diseases (asthma, immunosuppression, other co-morbidities non-specified) and dummy variables for health institutions. Robust estimates were used in all models. Data analysis was performed using the statistical software STATA20 and the statistical software R.21

Results

The database used in this study included information on 842 025 adults aged ≥20 years who were tested for COVID-19. Of these, 3600 (0.4%) observations were eliminated for not having information related to NCD diagnosis. We analysed only information on confirmed SARS-Cov-2 cases (n = 406 966). Of these, 53.2% were men (mean age, 47.0 years: 95% CI, 46.9, 47.1) and 46.5% women (mean age, 45.6 years; 95% CI, 45.6, 45.7).

Participants’ characteristics by sex are described in Table 1. The prevalence of NCDs was similar between the sexes. The most common NCD was HBP (20.6%; 95% CI, 20.5, 20.8), followed by obesity (19.8%; 95% CI, 19.6, 19.8) and diabetes (16.8%; 95% CI, 16.7%, 16.9). Furthermore, 55.8% (95% CI, 55.6, 56.0) reported having no NCDs, whereas 25.9% (95% CI, 25.8, 26.1) reported having one, 12.1% (95% CI, 12.0, 12.3) reported having two and 5.9% (95% CI, 5.9, 6.0) had three or more. Over half of the cases were reported by units from the Ministry of Health (53.7%; 95% CI, 53.5, 53.8), followed by the IMSS (33.0%; 95% CI, 32.8, 33.1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Mexican adults with diagnosis of COVID-19 and non-communicable diseases (NCDs) by sex

| Total |

Women |

Men |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | (95% CI) | N | % | (95% CI) | n | % | (95% CI) | |

| Total | 406 996 | 100 | – | 190 088 | 46.7 | (46.5, 46.8) | 216 908 | 53.2 | (53.1, 53.4) |

| Age in years | |||||||||

| 20–39 | 154 375 | 37.9 | (37.7, 38.0) | 75 687 | 39.8 | (39.5, 40.0) | 78 688 | 36.2 | (36.0, 36.4) |

| 40–59 | 169 361 | 41.6 | (41.4, 41.7) | 78 012 | 41.0 | (40.8, 41.2) | 91 349 | 42.1 | (41.9, 42.3) |

| 60–79 | 72 409 | 17.7 | (17.6, 17.9) | 31 508 | 16.5 | (16.4, 16.7) | 40 901 | 18.8 | (18.6, 19.0) |

| ≥80 | 10 851 | 2.6 | (2.6, 2.7) | 4881 | 2.5 | (2.4, 2.6) | 5970 | 2.7 | (2.6, 2.8) |

| NCDs | |||||||||

| Cardiovascular disease | |||||||||

| No | 398 168 | 97.8 | (97.7, 97.8) | 186 293 | 98.0 | (97.9, 98.0) | 211 875 | 97.6 | (97.6, 97.7) |

| Yes | 8828 | 2.1 | (2.1, 2.2) | 3795 | 1.9 | (1.9, 2.0) | 5033 | 2.3 | (2.2, 2.3) |

| Hypertension | |||||||||

| No | 323 624 | 79.5 | (79.3, 79.6) | 150 661 | 79.2 | (79.0, 79.4) | 172 963 | 79.7 | (79.5, 79.9) |

| Yes | 83 372 | 20.4 | (20.3, 20.6) | 39 427 | 20.7 | (20.5, 20.9) | 43 945 | 20.2 | (20.0, 20.4) |

| Chronic kidney diseases | |||||||||

| No | 398 660 | 97.9 | (97.9, 97.9) | 186 490 | 98.1 | (98.0, 98.1) | 212 170 | 97.8 | (97.7, 97.8) |

| Yes | 8336 | 2.0 | (2.0, 2.0) | 3598 | 1.8 | (1.8, 1.9) | 4738 | 2.1 | (2.1, 2.2) |

| Diabetes | |||||||||

| No | 339 625 | 83.4 | (83.3, 83.5) | 158 970 | 83.6 | (83.4, 83.7) | 180 655 | 83.2 | (83.1, 83.4) |

| Yes | 67 371 | 16.5 | (16.4, 16.6) | 31 118 | 16.3 | (16.2, 16.5) | 36 253 | 16.7 | (16.5, 16.8) |

| Obesity | |||||||||

| No | 328 251 | 80.6 | (80.5, 80.7) | 151 476 | 79.6 | (79.5, 79.8) | 176 775 | 81.4 | (81.3, 81.6) |

| Yes | 78 745 | 19.3 | (19.2, 19.4) | 38 612 | 20.3 | (20.1, 20.4) | 40 133 | 18.5 | (18.3, 18.6) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | |||||||||

| No | 400 352 | 98.3 | (98.3, 98.4) | 186 895 | 98.3 | (98.2, 98.3) | 213 457 | 98.4 | (98.3, 98.4) |

| Yes | 6644 | 1.6 | (1.5, 1.6) | 3193 | 1.6 | (1.6, 1.7) | 3451 | 1.5 | (1.5, 1.6) |

| Number of NCDs | |||||||||

| 0 | 241 589 | 59.3 | (59.2, 59.5) | 113 244 | 59.5 | (59.3, 59.7) | 128 345 | 59.1 | (58.9, 59.3) |

| 1 | 100 464 | 24.6 | (24.5, 24.8) | 45 600 | 23.9 | (23.7, 24.1) | 54 864 | 25.2 | (25.1, 25.4) |

| 2 | 45 673 | 11.2 | (11.1, 11.3) | 21 545 | 11.3 | (11.1, 11.4) | 24 128 | 11.1 | (10.9, 11.2) |

| ≥3 | 19 270 | 4.7 | (4.6, 4.7) | 9699 | 5.1 | (5.0, 5.2) | 9571 | 4.4 | (4.3, 4.4) |

| Severity indicators | |||||||||

| Pneumonia | |||||||||

| No | 321 109 | 78.8 | (78.7, 79.0) | 157 201 | 82.7 | (82.5, 82.8) | 163 908 | 75.5 | (75.3, 75.7) |

| Yes | 85 881 | 21.1 | (20.9, 21.2) | 32 884 | 17.2 | (17.1, 17.4) | 52 997 | 24.4 | (24.2, 24.6) |

| Attention mode | |||||||||

| Ambulatory | 294 586 | 72.3 | (72.2, 72.5) | 146 841 | 77.2 | (77.0, 77.4) | 1477 45 | 68.1 | (67.9, 68.3) |

| Hospital admission | 112 410 | 27.6 | (27.4, 27.7) | 43 247 | 22.7 | (22.5, 22.9) | 69 163 | 3.2 | (31.6, 32.0) |

| Mechanically assisted intubation | |||||||||

| No | 396 337 | 97.3 | (97.3, 97.4) | 186 528 | 98.1 | (98.0, 98.1) | 209 809 | 96.7 | (96.6, 96.8) |

| Yes | 10 659 | 2.6 | (2.5, 2.6) | 3560 | 1.8 | (1.8, 1.9) | 7099 | 3.2 | (3.1, 3.3) |

| Admitted to unit and intensive care | |||||||||

| No | 398 193 | 97.8 | (97.7, 97.8) | 187 060 | 98.4 | (98.3, 98.4) | 211 133 | 97.3 | (97.2, 97.4) |

| Yes | 8803 | 2.1 | (2.1, 2.2) | 3028 | 1.5 | (1.5, 1.6) | 5775 | 2.6 | (2.5, 2.7) |

| Institutions of the health system | |||||||||

| Private | 11 992 | 2.9 | (2.8, 2.9) | 4790 | 2.5 | (2.4, 2.5) | 7202 | 3.3 | (3.2, 3.3) |

| SEMAR | 3184 | 0.7 | (0.7, 0.8) | 1040 | 0.5 | (0.5, 0.5) | 2144 | 0.9 | (0.9, 1.0) |

| SS | 218 544 | 53.6 | (53.5, 53.8) | 104 574 | 55.0 | (54.7, 55.2) | 113 970 | 52.5 | (52.3, 52.7) |

| Others | 762 | 0.1 | (0.1, 0.2) | 380 | 0.1 | (0.1, 0.2) | 382 | 0.1 | (0.1, 0.1) |

| SEDENA | 2831 | 0.6 | (0.6, 0.7) | 943 | 0.4 | (0.4, 0.5) | 1888 | 0.8 | (0.8, 0.9) |

| Not specified | 3148 | 0.7 | (0.7, 0.8) | 1416 | 0.7 | (0.7, 0.7) | 1732 | 0.7 | (0.7, 0.8) |

| SMH | 9186 | 2.2 | (2.2, 2.3) | 4537 | 2.3 | (2.3, 2.4) | 4649 | 2.1 | (2.0, 2.2) |

| PEMEX | 5106 | 1.2 | (1.2, 1.2) | 1793 | 0.9 | (0.8, 0.9) | 3313 | 1.5 | (1.4, 1.5) |

| ISSSTE | 18 026 | 4.4 | (4.3, 4.4) | 8401 | 4.4 | (4.3, 4.5) | 9625 | 4.4 | (4.3, 4.5) |

| IMSS | 134 217 | 32.9 | (32.8, 33.1) | 62 214 | 32.7 | (32.5, 32.9) | 72 003 | 33.1 | (32.9, 33.3) |

Data from General Direction of Health Information (DGIS), 2020.

Ministry of Health, Ministry of the Navy (SEMAR), Federal Ministry of Health (SS), Other (Red Cross, DIF, Municipal, Universitary), Ministry of National Defense (SEDENA), Statal Ministry of Health (SMH), Petroleos Mexicanos (PEMEX), Institute of Security and Social Services for State Workers (ISSSTE), Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS).

Table 2 shows the CFR for SARS-Cov-2 by sex and NCDs. In the total population, the average CFR was 12.1% (95% CI, 12.0, 12.2) and was higher among men (CFR 14.6%; 95% CI, 14.5, 14.8) than women (CFR 9.1%; 95% CI, 9.0, 9.3). Trend analyses showed that the CFR increased with age and number of NCDs (trend test p < 0.001). In women, the CFR was 1.2% in the 20- to 39-year-old age group and 40.8% in the ≥80 years group, whereas, for men, it was 2.6% and 47.9%, respectively.

Table 2.

Case-fatality rate (CFR) in Mexican adults diagnosed with COVID-19 and non-communicable diseases (NCDs) by sex.

| Total |

Women |

Men |

Womena vs men |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | CFR % | (95% CI) | RRb | (95% CI)d | n | CFR % | (95% CI) | RRc | (95% CI)d | N | CFR % | (95% CI)d | RRc | (95% CI) | RR by sex | (95% CI)d | P-valuef | ||

| Sex | 406 996 | 11.2 | (11.1, 11.3) | – | – | 190 088 | 8.4 | (8.3, 8.6) | – | – | 216 908 | 13.7 | (13.6, 13.9) | – | – | 1.5 | (1.4, 1.5) | <0.001 | |

| Age group | |||||||||||||||||||

| 20–39a | 154 375 | 1.7 | (1.6, 1.8) | 1 | – | 75 687 | 1.1 | (1.0, 1.1) | 1 | – | 78 688 | 2.3 | (2.1, 2.5) | 1 | – | 2.0 | (1.9, 2.2) | <0.001 | |

| 40–59 | 169 361 | 9.8 | (9.6, 9.9) | 5.5 | (5.3, 5.7) | 78 012 | 6.7 | (6.7, 6.8) | 6.1 | (5.6, 6.5) | 91 349 | 12.4 | (12.2, 12.6) | 5.2 | (4.9, 5.4) | 1.7 | (1.7, 1.8) | <0.001 | |

| 60–79 | 72 409 | 30.2 | (29.9, 30.6) | 16.8 | (16.2, 17.5) | 31 508 | 25.7 | (25.6, 5.8) | 23.2 | (21.6, 24.8) | 40 901 | 33.7 | (33.5, 34.0) | 14.1 | (13.5, 14.8) | 1.3 | (1.2, 1.3) | <0.001 | |

| ≥80 | 10 851 | 43.2 | (42.3, 44.2) | 24.2 | (23.1, 25.2) | 4881 | 39.0 | (38.9, 9.0) | 35.1 | (32.6, 37.9) | 5970 | 46.7 | (46.5, 46.9) | 19.6 | (18.6, 20.6) | 1.1 | (1.1, 1.2) | <0.001 | |

| p trend | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |||||||||||||||

| NCCDs | |||||||||||||||||||

| Cardiovascular disease | |||||||||||||||||||

| Noa | 398 168 | 10.9 | (10.8, 11.0) | 1 | – | 186 293 | 8.1 | (8.0, 8.2) | 1 | – | 211 875 | 13.3 | (12.0, 14.6) | 1 | – | 1.5 | (1.5, 1.5) | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 8828 | 27.7 | (26.7, 28.6) | 1.1 | (1.0, 1.1) | 3795 | 24.0 | (23.8, 4.1) | 1.2 | (1.1, 1.3) | 5033 | 30.4 | (29.2, 31.7) | 1.1 | (1.1, 1.2) | 1.2 | (1.1, 1.3) | <0.001 | |

| Hypertension | |||||||||||||||||||

| Noa | 323 624 | 7.9 | (7.8, 8.0) | 1 | – | 150 661 | 5.1 | (5.0, 5.2) | 1 | – | 172 963 | 10.4 | (9.9, 10.8) | 1 | – | 1.7 | (1.6, 1.7) | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 83 372 | 24.2 | (23.9, 24.5) | 1.4 | (1.4, 1.5) | 39 427 | 21.2 | (21.0, 1.3) | 1.6 | (1.6, 1.7) | 43 945 | 26.9 | (26.5, 27.3) | 1.3 | (1.3, 1.3) | 1.3 | (1.2, 1.3) | <0.001 | |

| Chronic kidney diseases | |||||||||||||||||||

| Noa | 398 660 | 10.7 | (10.6, 10.8) | 1 | – | 186 490 | 7.9 | (7.8, 8.1) | 1 | – | 212 170 | 13.1 | (11.7, 14.5) | 1 | – | 1.5 | (1.5, 1.5) | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 8336 | 37.5 | (36.5, 38.6) | 2.0 | (2.0, 2.1) | 3598 | 34.8 | (34.7, 34.9) | 2.4 | (2.3, 2.6) | 4738 | 39.6 | (38.2, 41.0) | 1.8 | (1.8, 1.9) | 1.1 | (1.0, 1.1) | <0.001 | |

| Diabetes | |||||||||||||||||||

| Noa | 339 625 | 8.3 | (8.2, 8.4) | 1 | – | 158 970 | 5.6 | (5.5, 5.8) | 1 | – | 180 655 | 10.7 | (10.2, 11.2) | 1 | – | 1.6 | (1.6, 1.7) | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 67 371 | 26.0 | (25.6, 26.3) | 1.7 | (1.6, 1.7) | 31 118 | 22.7 | (22.6, 22.8) | 1.9 | (1.9, 2.0) | 36 253 | 28.7 | (28.3, 29.2) | 1.5 | (1.5, 1.6) | 1.2 | (1.2, 1.3) | <0.001 | |

| Obesity | |||||||||||||||||||

| Noa | 328 251 | 10.5 | (10.4, 10.6) | 1 | – | 151 476 | 7.5 | (7.4, 7.6) | 1 | – | 176 775 | 13.1 | (12.6, 13.4) | 1 | – | 1.5 | (1.5, 1.5) | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 78 745 | 14.5 | (14.2, 14.7) | 1.4 | (1.4, 1.4) | 38 612 | 12.1 | (11.9, 12.2) | 1.5 | (1.4, 1.5) | 40 133 | 16.8 | (16.4, 17.2) | 1.4 | (1.3, 1.4) | 1.4 | (1.4, 1.5) | <0.001 | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | |||||||||||||||||||

| Noa | 400 352 | 10.9 | (10.8, 11.0) | 1 | – | 186 895 | 8.1 | (7.9, 8.2) | 1 | – | 213 457 | 13.3 | (11.7, 14.9) | 1 | – | 1.5 | (1.5, 1.5) | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 6644 | 33.3 | (32.2, 34.5) | 1.1 | (1.1, 1.2) | 3193 | 30.0 | (29.8, 30.1) | 1.2 | (1.1, 1.2) | 3451 | 36.5 | (34.9, 38.1) | 1.1 | (1.0, 1.1) | 1.2 | (1.1, 1.3) | <0.001 | |

| Number of NCCDs | |||||||||||||||||||

| 0a | 241 589 | 5.8 | (5.7, 5.9) | 1 | – | 113 244 | 3.4 | (3.3, 3.5) | 1 | 128 345 | 8.0 | (7.7, 8.3) | 1 | 1.9 | (1.8, 1.9) | <0.001 | |||

| 1 | 100 464 | 14.3 | (14.1, 14.5) | 1.6 | (1.5, 1.6) | 45 600 | 10.6 | (10.5, 10.7) | 1.8 | (1.7, 1.9) | 54 864 | 17.4 | (17.1, 17.7) | 1.5 | (1.4, 1.5) | 1.5 | (1.5, 1.6) | <0.001 | |

| 2 | 45 673 | 24.1 | (23.7, 24.5) | 2.0 | (1.9, 2.1) | 215 45 | 20.7 | (20.6, 20.8) | 2.5 | (2.4, 2.6) | 241 28 | 27.2 | (26.8, 27.5) | 1.7 | (1.7, 1.8) | 1.3 | (1.2, 1.3) | <0.001 | |

| >2 | 19 270 | 32.8 | (32.1, 33.5) | 2.4 | (2.4, 2.5) | 9699 | 29.9 | (29.8, 30.0) | 3.2 | (3.0, 3.3) | 9571 | 35.8 | (35.4, 36.1) | 2.1 | (2.0, 2.2) | 1.2 | (1.1, 1.2) | <0.001 | |

| p trend | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Severity indicators | |||||||||||||||||||

| Pneumonia | |||||||||||||||||||

| Noa | 321 109 | 3.6 | (3.5, 3.6) | 1 | – | 157 201 | 2.5 | (2.4, 2.6) | 1 | – | 163 908 | 4.6 | (4.1, 5.0) | 1 | – | 1.7 | (1.6, 1.7) | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 85 881 | 40.0 | (39.7, 40.3) | 6.6 | (6.5, 6.8) | 32 884 | 36.7 | (36.6, 36.8) | 8.1 | (7.8, 8.4) | 52 997 | 42.1 | (41.6, 42.4) | 5.9 | (5.7, 6.0) | 1.1 | (1.1, 1.1) | <0.001 | |

| Attention mode | |||||||||||||||||||

| Hospital admission | |||||||||||||||||||

| Noa | 294 586 | 1.7 | (1.6, 1.7) | 1 | – | 146 841 | 1.1 | (1.1, 1.2) | 1 | – | 147 745 | 2.2 | (1.9, 2.6) | 1 | – | 1.9 | (1.7, 2.0) | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 112 410 | 36.3 | (36.0, 36.6) | 12.9 | (12.5, 13.3) | 43 247 | 33.2 | (33.2, 33.3) | 16.7 | (15.9, 17.7) | 69 163 | 38.2 | (37.8, 38.6) | 11.0 | (10.5, 11.4) | 1.1 | (1.1, 1.1) | <0.001 | |

| Mechanically assisted intubation | |||||||||||||||||||

| Noa | 396 337 | 9.6 | (9.5, 9.7) | 1 | – | 186 528 | 7.2 | (7.1, 7.3) | 1 | – | 209 809 | 11.7 | (10.7, 12.7) | 1 | – | 1.5 | (1.4, 1.5) | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 10 659 | 73.1 | (72.2, 73.9) | 4.1 | (4.0, 4.2) | 3560 | 72.8 | (72.6, 72.9) | 4.8 | (4.6, 5.0) | 7099 | 73.2 | (72.2, 74.2) | 3.8 | (3.7, 3.9) | 1 | (0.9, 1.0) | 0.0614 | |

| Admitted to unit and intensive care | |||||||||||||||||||

| Noa | 398 193 | 10.3 | (10.3, 10.4) | 1 | – | 187 060 | 7.8 | (7.7, 7.9) | 1 | – | 211 133 | 12.6 | (11.3, 13.9) | 1 | – | 1.5 | (1.4, 1.5) | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 8803 | 51.9 | (50.9, 53.0) | 2.8 | (2.7, 2.9) | 3028 | 48.8 | (48.7, 48.9) | 3.1 | (2.9, 3.2) | 5775 | 53.6 | (52.3, 54.9) | 2.7 | (2.6, 2.7) | 1.1 | (1.0, 1.1) | <0.001 | |

| Institutions of the health systeme | |||||||||||||||||||

| Private | 11 992 | 4.6 | (4.3, 5.0) | 1 | 4790 | 3.7 | (3.2, 4.3) | 1 | 7202 | 5.2 | (4.3, 6.2) | 1 | – | 1.5 | (1.2, 1.7) | <0.0001 | |||

| SEMAR | 3184 | 5.9 | (5.1, 6.7) | 1.4 | (1.2, 1.6) | 1040 | 7.0 | (6.4, 7.5) | 1.9 | (1.4, 2.4) | 2144 | 5.4 | (4.4, 6.4) | 1.2 | (0.9, 1.4) | 1 | (0.7, 1.3) | 0.4882 | |

| SS | 218 544 | 6.3 | (6.2, 6.4) | 1.5 | (1.4, 1.6) | 104 574 | 4.4 | (3.9, 5.0) | 1.4 | (1.2, 1.6) | 113 970 | 8.1 | (7.1, 9.0) | 1.6 | (1.5, 1.8) | 1.7 | (1.6, 1.8) | <0.0001 | |

| Others | 762 | 8.0 | (6.1, 9.9) | 1.3 | (1.0, 1.7) | 380 | 5.5 | (4.9, 6.0) | 1.2 | (0.8, 1.9) | 382 | 10.4 | (9.5, 11.4) | 1.4 | (1.0, 1.9) | 1.6 | (1.0, 2.6) | 0.0225 | |

| SEDENA | 2831 | 11.2 | (10.1, 12.4) | 2.2 | (1.9, 2.5) | 943 | 11.1 | (10.5, 11.6) | 2.5 | (2.0, 3.1) | 1888 | 11.3 | (10.3, 12.2) | 2.1 | (1.8, 2.4) | 1.1 | (0.9, 1.4) | 0.0623 | |

| Not specified | 3148 | 11.8 | (10.7, 13.0) | 2.3 | (2.1, 2.6) | 1416 | 7.9 | (7.4, 8.5) | 2.3 | (1.8, 2.8) | 1732 | 15.1 | (14.1, 16.0) | 2.4 | (2.1, 2.8) | 1.5 | (1.3, 1.9) | <0.0001 | |

| SMH | 9186 | 11.9 | (11.2, 12.6) | 2.5 | (2.3, 2.8) | 4537 | 8.7 | (8.2, 9.3) | 2.5 | (2.2, 3.0) | 4649 | 15.0 | (14.1, 16.0) | 2.6 | (2.3, 2.9) | 1.5 | (1.3, 1.6) | <0.0001 | |

| PEMEX | 5106 | 14.9 | (14.0, 15.9) | 2.3 | (2.1, 2.6) | 1793 | 14.3 | (13.7, 14.8) | 2.6 | (2.2, 3.1) | 3313 | 15.3 | (14.3, 16.2) | 2.2 | (2.0, 2.5) | 1.2 | (1.1, 1.4) | 0.0032 | |

| ISSSTE | 18 026 | 17.9 | (17.4, 18.5) | 2.9 | (2.7, 3.2) | 8401 | 13.7 | (13.1, 14.2) | 2.9 | (2.5, 3.3) | 9625 | 21.6 | (20.7, 22.6) | 2.9 | (2.7, 3.3) | 1.4 | (1.3, 1.5) | <0.0001 | |

| IMSS | 134 217 | 18.9 | (18.7, 19.1) | 3.8 | (3.5, 4.1) | 62 214 | 14.7 | (14.1, 15.2) | 4.0 | (3.5, 4.6) | 72 003 | 22.6 | (21.6, 23.6) | 3.7 | (3.4, 4.1) | 1.4 | (1.3, 1.4) | <0.0001 | |

Reference category.

RR = relative risk adjusted by age and sex.

RR adjusted by age.

RR = relative risk with 95% confidence interval.

Ministry of Health. Ministry of the Navy (SEMAR), Federal Ministry of Health (SS), Other (Red Cross, DIF, Municipal, Universitary), Ministry of National Defense (SEDENA), Statal Ministry of Health (SMH), Petroleos Mexicanos (PEMEX), Institute of Security and Social Services for State Workers (ISSSTE), Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS).

Differences women vs men.

Data from General Direction of Health Information (DGIS), Ministry of Health, 2020.

In the group of patients without NCDs and stratified by sex, the CFR was lower in women (3.4%; 95% CI, 3.3, 3.5) than in men (8.0%; 95% CI, 7.8, 8.1). When stratifying by type of institution, the CFR was higher in the IMSS (CFR , 10.7%; 95% CI, 10.5, 10.9), followed by the ISSSTE (CFR, 9.5%; 95% CI, 8.9, 10.1). In patients with at least three NCDs, the CFR was higher in women (CFR, 29.9%; 95% CI, 29.0, 30.0) than in men (CFR, 35.8%; 95% CI, 34.8, 36.7), whereas, when stratifying by type of institution, the CFR was higher in the IMSS (CFR, 44.0%; 95% CI, 42.9, 45.1), followed by the ISSSTE (CFR, 37.5%; 95% CI, 35.0, 40.1). The trend test by number of NCDs was p < 0.001 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Case-fatality rate (CFR) in Mexican adults diagnosed with COVID-19 and categorized by number of non-communicable diseases (NCDs)

| Variables | No NCDs |

One NCD |

Two NCDs |

Three NCDs |

Among NCDs | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | CFR % | (95% CI) | RR | n | CFR % | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | N | CFR % | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | n | CFR % | (95% CI) | RR | (95% CI) | p trend | |

| Sexc | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Womena | 113 244 | 3.4 | (3.3, 3.5) | 1.0 | 45 600 | 10.6 | (10.3, 10.9) | 1.8 | (1.7, 1.9) | 21 545 | 20.7 | (20.2, 21.3) | 2.5 | (2.5, 2.4) | 9699 | 29.9 | (29.0, 30.8) | 3.2 | (3.0, 3.3) | <0.0001 |

| Men | 128 345 | 8.0 | (7.8, 8.1) | 1.0 | 54 864 | 17.4 | (17.1, 17.7) | 1.5 | (1.4, 1.5) | 24 128 | 27.2 | (26.6, 27.7) | 1.7 | (1.7, 1.7) | 9571 | 35.8 | (34.8, 36.7) | 2.1 | (2.0, 2.2) | <0.0001 |

| Age groupd (years) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 20–39a | 120 764 | 0.9 | (0.9, 1.0) | 1.0 | 27 670 | 3.4 | (3.2, 3.7) | 3.5 | (3.2, 3.8) | 4924 | 8.3 | (7.5, 9.0) | 8.2 | (8.2, 7.3) | 1017 | 16.3 | (14.0, 18.5) | 16.1 | (13.8, 18.7) | <0.0001 |

| 40–59 | 93 176 | 6.0 | (5.9, 6.2) | 1.0 | 47 162 | 11.3 | (11.0, 11.6) | 1.8 | (1.8, 1.9) | 20 849 | 16.9 | (16.4, 17.4) | 2.8 | (2.8, 2.7) | 8174 | 25.5 | (24.5, 26.4) | 4.2 | (4.0, 4.4) | <0.0001 |

| 60–79 | 24 373 | 24.9 | (24.3, 25.4) | 1.0 | 22 093 | 29.4 | (28.8, 30.0) | 1.1 | (1.1, 1.2) | 17 169 | 34.1 | (33.4, 34.8) | 1.4 | (1.4, 1.3) | 8774 | 39.6 | (38.6, 40.6) | 1.6 | (1.6, 1.7) | <0.0001 |

| ≥80 | 3276 | 39.4 | (37.7, 41.1) | 1.0 | 3539 | 44.5 | (42.8, 46.1) | 1.1 | (1.0, 1.2) | 2731 | 45.0 | (43.1, 46.9) | 1.1 | (1.1, 1.1) | 1305 | 45.9 | (43.1, 48.6) | 1.1 | (1.1, 1.2) | <0.0001 |

| Severity indicators | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Pneumoniaa | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Noa | 208 529 | 1.7 | (1.7, 1.8) | 1.0 | 73 721 | 4.7 | (4.5, 4.8) | 1.6 | (1.5, 1.7) | 28 437 | 9.8 | (9.5, 10.2) | 2.3 | (2.3, 2.2) | 10 422 | 15.7 | (15.0, 16.4) | 3.2 | (3.0, 3.4) | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 33 056 | 31.8 | (31.3, 32.3) | 1.0 | 26 742 | 40.9 | (40.3, 41.5) | 1.1 | (1.1, 1.1) | 17 235 | 47.7 | (46.9, 48.4) | 1.2 | (1.2, 1.2) | 8848 | 52.9 | (51.9, 54.0) | 1.3 | (1.3, 1.4) | <0.0001 |

| Attention mode | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hospital admissiona | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Noa | 198 400 | 0.8 | (0.7, 0.8) | 1.0 | 65 886 | 2.3 | (2.2, 2.5) | 1.7 | (1.6, 1.9) | 22 767 | 5.2 | (4.9, 5.5) | 2.6 | (2.6, 2.4) | 7533 | 9.1 | (8.4, 9.7) | 3.8 | (3.5, 4.2) | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 43 189 | 29.0 | (28.6, 29.4) | 1.0 | 34 578 | 37.1 | (36.6, 37.6) | 1.1 | (1.1, 1.1) | 22 906 | 42.9 | (42.2, 43.5) | 1.2 | (1.2, 1.2) | 11 737 | 48.0 | (47.1, 48.9) | 1.3 | (1.3, 1.4) | <0.0001 |

| Mechanically assisted intubationa | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Noa | 238 182 | 4.9 | (4.8, 5.0) | 1.0 | 96 958 | 12.2 | (11.9, 12.4) | 1.5 | (1.5, 1.6) | 43 224 | 21.2 | (20.8, 21.6) | 2.0 | (2.0, 1.9) | 17 973 | 29.5 | (28.8, 30.1) | 2.5 | (2.4, 2.6) | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 3407 | 68.6 | (67.0, 70.2) | 1.0 | 3506 | 73.6 | (72.2, 75.1) | 1.0 | (1.0, 1.0) | 2449 | 75.2 | (73.5, 76.9) | 1.0 | (1.0, 1.0) | 1297 | 79.1 | (76.8, 81.3) | 1.1 | (1.0, 1.1) | <0.0001 |

| Admitted to unit and intensive caree | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Noa | 238 685 | 5.3 | (5.2, 5.4) | 1.0 | 97 496 | 13.1 | (12.9, 13.3) | 1.5 | (1.5, 1.6) | 43 750 | 22.8 | (22.4, 23.2) | 2.0 | (2.0, 1.9) | 18 262 | 31.2 | (30.5, 31.9) | 2.5 | (2.4, 2.5) | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 2904 | 46.2 | (44.3, 48.0) | 1.0 | 2968 | 52.6 | (50.8, 54.4) | 1.0 | (1.0, 1.1) | 1923 | 54.6 | (52.4, 56.8) | 1.1 | (1.1, 1.0) | 1008 | 61.7 | (58.7, 64.7) | 1.2 | (1.1, 1.3) | <0.0001 |

| Institutions of the health systembe,b | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Privatea | 7994 | 1.9 | (1.6, 2.2) | 1.0 | 2555 | 6.6 | (5.6, 7.6) | 2.1 | (1.6, 2.6) | 1038 | 14.2 | (12.1, 16.3) | 3.2 | (3.2, 2.5) | 405 | 21.9 | (17.9, 26.0) | 4.2 | (3.2, 5.5) | <0.0001 |

| SEMAR | 2407 | 2.0 | (1.5, 2.6) | 1.0 | 461 | 13.6 | (10.5, 16.8) | 3.4 | (2.3, 5.1) | 215 | 21.8 | (16.3, 27.3) | 3.7 | (3.7, 2.4) | 101 | 29.7 | (20.7, 38.6) | 4.8 | (3, 7.9.0) | |

| SS | 136 772 | 3.1 | (3.0, 3.2) | 1.0 | 53 198 | 8.9 | (8.6, 9.1) | 1.9 | (1.8, 1.9) | 21 062 | 15.3 | (14.8, 15.8) | 2.4 | (2.4, 2.3) | 7512 | 20.7 | (19.8, 21.6) | 3.1 | (2.9, 3.3) | <0.0001 |

| Others | 413 | 2.6 | (1.1, 4.2) | 1.0 | 190 | 12.6 | (7.8, 17.3) | 2.9 | (1.4, 5.7) | 101 | 13.8 | (7.0, 20.6) | 2.0 | (2.0, 0.8) | 58 | 20.6 | (10.1, 31.2) | 3.0 | (1.3, 6.8) | <0.0001 |

| SEDENA | 1827 | 7.2 | (6.0, 8.4) | 1.0 | 603 | 15.2 | (12.3, 18.1) | 1.2 | (0.9, 1.6) | 300 | 24.6 | (19.7, 29.5) | 1.4 | (1.4, 1.0) | 101 | 19.8 | (11.9, 27.6) | 1.2 | (0.7, 1.9) | <0.0001 |

| Not specified | 1681 | 6.7 | (5.5, 7.9) | 1.0 | 907 | 14.7 | (12.4, 17.0) | 1.4 | (1.1, 1.8) | 398 | 20.8 | (16.8, 24.8) | 1.6 | (1.6, 1.2) | 162 | 26.5 | (19.7, 33.3) | 1.7 | (1.2, 2.4) | <0.0001 |

| SMH | 5308 | 7.1 | (6.4, 7.8) | 1.0 | 2253 | 14.2 | (12.7, 15.6) | 1.3 | (1.1, 1.5) | 1076 | 20.9 | (18.4, 23.3) | 1.4 | (1.4, 1.2) | 549 | 31.3 | (27.4, 35.2) | 1.6 | (1.4, 1.9) | <0.0001 |

| PEMEX | 1502 | 6.9 | (5.6, 8.2) | 1.0 | 1970 | 12.2 | (10.7, 13.6) | 1.3 | (1.1, 1.6) | 984 | 21.6 | (19.0, 24.2) | 1.7 | (1.7, 1.3) | 650 | 31.8 | (28.2, 35.4) | 2.1 | (1.7, 2.6) | <0.0001 |

| ISSSTE | 9079 | 9.5 | (8.9, 10.1) | 1.0 | 4756 | 20.9 | (19.8, 22.1) | 1.4 | (1.3, 1.6) | 2799 | 30.5 | (28.8, 32.2) | 1.7 | (1.7, 1.6) | 1392 | 37.5 | (35.0, 40.1) | 2.1 | (1.9, 2.3) | <0.0001 |

| IMSS | 74 606 | 10.7 | (10.5, 10.9) | 1.0 | 33 571 | 22.7 | (22.2, 23.1) | 1.4 | (1.3, 1.4) | 17 700 | 34.7 | (34.0, 35.4) | 1.6 | (1.6, 1.5) | 8340 | 44.0 | (42.9, 45.1) | 1.9 | (1.8, 1.9) | <0.0001 |

Data from General Direction of Health Information (DGIS), Ministry of Health, 2020.

Reference category.

Ministry of Health, Ministry of the Navy (SEMAR), Federal Ministry of Health (SS), Other (Red Cross, DIF, Municipal, Universitary), Ministry of National Defense (SEDENA), Statal Ministry of Health (SMH), Petroleos Mexicanos (PEMEX), Institute of Security and Social Services for State Workers (ISSSTE), Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS). cAdjusted by age continuous. dAdjusted by sex. eAdjusted by age continuous and sex.

Figure 1 shows that the CFR increases with the number of NCDs in a triple interaction (p < 0.01) with sex and age. Adults aged 20–29 years with at least three NCDs have a greater risk compared with those without NCDs, in women (RR, 46.6; 95% CI, 28.2, 76.9) and men (RR, 16.5; 95% CI, 9.9, 27.3). Moreover, the risk among adults aged ≥80 years with at least three NCDs compared with those without NCDs is 1.2 in women (95% CI, 1.0, 1.3) and 1.0 in men (95% CI, 0.9, 1.1). The model is shown in Supplementary Appendix 1, available as Supplementary data at IJE online, and Table 1.

Figure 1.

Case-fatality rate (CFR) estimate in adults with COVID-19 and number of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), categorized by age groups and sex. Estimations adjusted by categories of the institutions of the health system, asthma, immunosuppression and other non-specified co-morbidities. RR, relative risk (95% IC) no NCDs vs three or more NCDs. Data from General Direction of Health Information (DGIS), Ministry of Health, 2020.

The CFR for SARS-Cov-2 in men and women by number and all possible combinations of NCDs is shown in Supplementary Appendix 2, available as Supplementary data at IJE online, and Table 1. For two NCDs, the combination with the greatest CFR was T2D+CKD (CFR, 44.0; 95% CI, 39.2, 48.8); for three NCDs, it was T2D+COPD+CVD (CFR, 57.5; 95% CI, 38.4, 75.8).

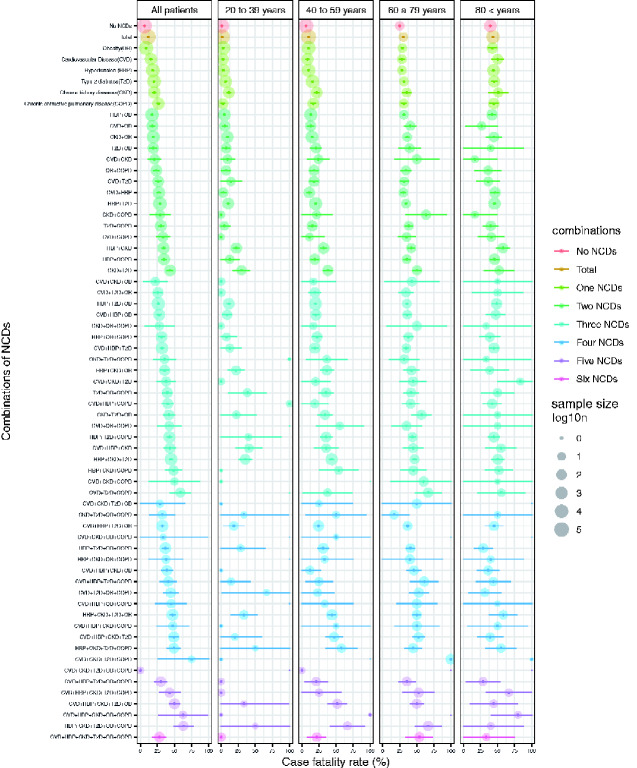

When categorizing by number of NCDs (from none to at least three), and disaggregating by age group, a greater risk of mortality for older age was found in all categories, except for T2D+COPD and CVD+CKD combinations. The combinations with the highest CFR (from 50.0% to 75.0%) were: CVD+HBP+CKD+T2D+OB, CVD+CKD+COPD, CVD+T2D+COPD, CVD+HBP+CKD+OB+COPD, HBP+CKD+T2D+OB+COPD, CVD+CKD+T2D+COPD; and 31 combinations with CFR between 30.0% and 49.0% were observed. The lowest CFRs were with OB or no NCDs (Figure 2). We did not see a specific pattern by sex (Supplementary Appendix 3, available as Supplementary data at IJE online, and Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 2.

Case-fatality rate and combinations of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) by age groups. Data from General Direction of Health Information (DGIS), Ministry of Health, 2020.

Figures 3–5 show the CFR by age groups for each NCD (T2D, HBP, OB, CKD, COPD and CVD) individually and combined with other NCDs. Figure 3a and b shows that younger adults had a higher RR of death when they had T2D combined with one or more NCDs (women: RR, 12.5; 95% CI, 7.1, 22.2; men: RR, 5.8, CI 95% 3.1, 10.9). A similar pattern was observed in all diseases and combinations in the age group of ≥60 years. The model is shown in Supplementary Appendix 1, available as Supplementary data at IJE online, and Table 2.

Figure 3.

Case-fatality rate (CFR) in adults with COVID-19 with/without diabetes or hypertension, with/without other non-communicable diseases (NCDs). Estimations adjusted by categories of the institutions of the health system, asthma, immunosuppression and other non-specified co-morbidities. Data from General Direction of Health Information (DGIS), Ministry of Health, 2020.

Figure 4.

Case-fatality rate (CFR) in adults with COVID-19 with/without obesity or chronic kidney disease, with/without other non-communicable diseases (NCDs). Estimations adjusted by categories of the institutions of the health system, asthma, immunosuppression and other non-specified co-morbidities. Data from General Direction of Health Information (DGIS), Ministry of Health, 2020.

Figure 5.

Case-fatality rate (CFR) in adults with COVID-19 with/without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or cardiovascular disease, with/without other non-communicable diseases (NCDs). Estimations adjusted by categories of the institutions of the health system, asthma, immunosuppression and other non-specified co-morbidities. Data from General Direction of Health Information (DGIS), Ministry of Health, 2020.

Discussion

In our analysis, the CFR was associated with sex, age and number of NCDs (HBP, obesity, CVD, CKD or COPD). We observed greater CFR heterogeneity among institutions.

There is evidence that a country’s average age can explain up to 66% of the variation in CFR for COVID-19.22 Much of the variation between countries is due to the age of people evaluated and diagnosed with the virus. In our analysis, the average age of the population infected with SARS-Cov-2 was 45 years, similarly to that in China (49 years) but younger than that in Italy (62 years).2 This could be due to the fact that the median age is similar in Mexico (30 years)3 and China (35 years),4 but higher in Italy (46 years).4

Adults with underlying NCDs are more likely to experience more severe symptoms or die from a SARS-Cov-2 infection.23 In our analysis, 40.5% of adults with SARS-Cov-2 had at least one NCD. This is lower than the prevalence found in the general Mexican adult population, in which 49.2% have at least one NCD.24

On the other hand, men have fewer antibodies that decrease the expression of IL-6, which is linked to deregulation of the immune system and lung damage. Likewise, men have higher concentrations of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in the alveolar membrane of the lungs through which SARS-CoV-2 enters and infects its host.25 Consistently with this infection mechanism and men’s diminished immune-system response, the CFR in our study was higher in men (CFR, 14.6) than in women (CFR, 9.1).

The number of chronic co-morbidities influences the risk of being infected with SARS-Cov-2 and dying from it.26 People with more NCDs and of older age have a higher risk of death.10 In China, reports indicate that, among people ≥60 years old, the risk of death was greater among those with two or more NCDs (RR, 2.59) in comparison to those with only one NCD (RR, 1.79).11–16 This is consistent with our findings, where risk of death was also greater in adults ≥60 years old and those with two or more NCDs (RR, 24.1) vs those with one (RR, 14.3).

Regardless of age, adults with SARS-Cov-2 and co-morbidities are at increased risk of death. Adults with SARS-Cov-2 and COPD have a higher expression of the functional receptor in the lower respiratory tract and this explains the extent of damage and the increased risk of death in patients with COPD and SARS-CoV-2.27 COPD combined with CVD or CKD significantly increases the risk of death, due to the systemic inflammatory response induced by hypoxia, as well as the homeostatic imbalance caused by CKD.28–30 The combination of three NCDs with the highest CFR among Mexicans was CVD+T2D+COPD. This combination is one of the most common in adults worldwide28 and can be attributed to the fact that multiorgan failure is associated with elevated plasminogen levels, leading to coronary thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.31 In general, we found that a greater number of NCDs increases the CFR because it reflects multiple-organ dysfunction, severity and worse prognosis. 32,33

We observe a triple interaction between the number of NCDs, age and sex. In the group aged 20–29 years, the RR of death when having at least three NCDs compared with not having any NCDs was higher in women (RR, 46.6) than in men (RR, 16.5), unlike that in the age group ≥80 years old, in which the RR was similar between women (RR, 1.0) and men (RR, 1.2). The greater RR in women aged 20–29 years is explained by the low CFR when they did not have any NCDs (women, 0.37%; men, 0.82%) and the higher CFR observed in women when they presented with at least three NCDs (women, 16.9%; men, 12.9%). In the youngest age group (20–29 years), women with at least NCDs had a higher CFR than men. This can be explained because the youngest have risk behaviours such as high alcohol and tobacco consumption that contribute to the generation of NCDs at very early ages34 but, in Mexico, these risk behaviours are more frequent in women than in men.35,36

We observed similar associations in other publications that use the same sources.13–14–15–37 However, our research was an exhaustive analysis that focused on the effect of six NCDs. This considers that they have a similar physiopathology, based on expression of ACE2 and a deficient immune system in diabetics that delays the phagocytic and antibacterial activity of neutrophils and macrophages together with oxidative stress that also exacerbates the chronic inflammatory processes.37,38 Thus, the smoking variable was eliminated because we do not believe it captures the tobacco habit in a robust way, as proposed by international expert recommendations.39

In Mexico, the difference observed in the CFR by institution providing health services may be due to the type of users treated (with formal employment or without employment, with different levels of poverty and different ages of the beneficiaries). It could also be due to the limited material and personnel infrastructure that local public institutions have (less testing capacity, especially at the beginning of the pandemic). In comparison, federal public institutions and private institutions have more availability of therapeutic supplies and intensive-care equipment. In our study, the CFR was lower in private institutions and federal public institutions. To explain these differences in more detail, a more comprehensive analysis is needed in the future.40,41

Limitations

We acknowledge that the main limitation of our study lies within its design, considering it is an observational study. This impedes us from making precise inferences or assuming causal relationships. We lacked information on clinical biomarkers at the time of registration to evaluate the baseline health status of the patients with SARS-Cov-2. With this information, we could have estimated, with less error and/or confounders, the effect of NCDs on mortality from SARS-Cov-2.

Another possible limitation is due to the data source, which was compiled through the Ministry of Health Epidemiologic Surveillance System and favours surveillance of high-risk cases or specific risk factors. This increases the probability of registering cases with severe symptoms and under-representing cases with lower risk who have moderate symptoms.

A third limitation of this study is that, to preserve the confidentiality of participants, the database does not include the specific medical unit in which the patients received care. It did not allow us to control for the specific effect of each healthcare unit and the clustering of observations at the healthcare unit, which may affect mainly the variance of our estimates.

A strength of our study is that it is the first to examine the association between CFR and NCDs in SARS-Cov-2 patients by correcting for the institution of care in all data of Mexican adults registered as SARS-Cov-2-positive. Our findings are consistent with those of other publications that state that NCDs increase mortality in SARS-Cov-2 cases. It therefore contributes to a better understanding of the interaction between SARS-Cov-2 and pre-existing NCDs.

Conclusion

We found that, among Mexican adults, mortality from SARS-Cov-2 increases with the number of NCDs. The combination of diseases such as T2D, CKD, COPD and CVD that were diagnosed in young people may mean that Mexicans are exposed early to risk factors like alcohol and tobacco intake, adiposity and poor diet, and in greater magnitude. This accelerates disease onset and may explain the higher mortality in young Mexicans. Our findings are consistent with the scientific literature and contribute to the understanding of these associations. More studies are needed to understand the heterogeneity observed by mortality and type of health institution. The evidence generated by this study can be useful for decision makers in the health sector, at both population and clinical levels.

Ethics approval

The study does not require ethical review because it is based on open, anonymized data from the Mexican Ministry of Health.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at IJE online.

Author contributions

E.M.F., M.R.V., S.B.C. and I.C.N.: conceptualized the research; E.M.F. and B.H.: analysed the data; M.R.V., J.E.M. and I.C.N.: investigation; M.R.V., J.E.M., I.C.N., E.M.F. and I.C.N.: methodology; M.R.V., J.E.M., I.C.N. and E.M.F.: supervision; E.M.F., M.R.V., J.E.M., B.H., S.B.C., V.E.V.D. and I.C.N.: writing, review and editing.

Funding

We did not receive funding for this investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The original data are public in https://www.gob.mx/salud/documentos/datos-abiertos-152127.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1. Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. The Species severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and Naming It SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol 2020;5:536–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet 2020;395:507–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang D Hu B Hu C et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020;323:1061. 10.1001/jama.2020.1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Johns Hopkins University. Mortality Analysis EE. UU. Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, 2020.. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality (10 December 2020, date last accessed)

- 5. WHO. Coronavirus Disease Outbreak (COVID-19). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2020. https://www.who.int/es/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public/q-a-coronaviruses. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:1054–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rod JE, Oviedo-Trespalacios O, Cortes-Ramirez J. A brief-review of the risk factors for COVID-19 severity. Rev Saúde Pública 2020;54:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 2020;323:1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li X Xu S Yu M et al. Risk factors for severity and mortality in adult COVID-19 inpatients in Wuhan. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2020;146:110–8. 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang J, Wang X, Jia X et al. Risk factors for disease severity, unimprovement, and mortality in COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020;26:767–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zheng Z Peng F Xu B et al. Risk factors of critical & mortal COVID-19 cases: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Journal of Infection 2020;81:e16–25. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Denova-Gutiérrez E, Lopez-Gatell H, Alomia-Zegarra JL et al. The association of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension with severe coronavirus disease 2019 on admission among Mexican patients. Obesity 2020;28:1826–32; 10.1002/oby.22946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bello-Chavolla OY, Bahena-López JP, Antonio-Villa NE et al. Predicting mortality due to SARS-CoV-2: a mechanistic score relating obesity and diabetes to COVID-19 outcomes in Mexico. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020;105:2752–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bello-Chavolla OY, Bahena-Lopez JP, Antonio-Villa NE et al. Predicting mortality due to SARS-CoV-2: a mechanistic score relating obesity and diabetes to COVID-19 outcomes in Mexico. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020;105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Campos-Nonato I, Hernandez-Barrera L, Pedroza-Tobias A, Medina C, Barquera S. Hypertension in Mexican adults: prevalence, diagnosis and type of treatment. Ensanut MC 2016. Salud Publica Mex 2018;60:233–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Campos-Nonato I, Ramirez-Villalobos M, Flores-Coria A, Valdez A, Monterrubio-Flores E. Prevalence of previously diagnosed diabetes and glycemic control strategies in Mexican adults: ENSANUT-2016. PLoS One 2020;15:e0230752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. WHO. Noncommunicable Diseases (NCD) Country Profiles. Mexico. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Secretaria de Salud. Lineamiento estandarizado para la vigilancia epidemiológica y por laboratorio de la enfermedad respiratoria viral. Dirección General de Epidemiología: SSA, 2020. http://www.gob.mx/salud.

- 19. World Health Organization. Laboratory Testing of Human Suspected Cases of Novel Coronavirus (nCoV) Infection—Interim Guidance. Berlin: WHO, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20. StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21. R Core Team (2020). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sudharsanan N, Didzun O, Barnighausen T, Geldsetzer P. The contribution of the age distribution of cases to COVID-19 case fatality across countries: a 9-country demographic study. Ann Intern Med 2020;173:714–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haybar H, Kazemnia K, Rahim F. Underlying chronic disease and COVID-19 Infection: a state-of-the-artreview. J Chronic Dis Care 2020;e103452. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shamah-Levy T, Cuevas-Nasu L, Romero-Martínez M, Rivera-Dommarco J, Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2018. Resultados Nacionales. Cuernavaca: Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jin JM, Bai P, He W et al. Gender differences in patients with COVID-19: focus on severity and mortality. Front Public Health 2020;8:152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Martini N, Piccinni C, Pedrini A, Maggioni A. COVID-19 and chronic diseases: current knowledge, future steps and the MaCroScopio project. Recenti Prog Med 2020;111:198–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Leung JM, Yang CX, Tam A et al. ACE-2 expression in the small airway epithelia of smokers and COPD patients: implications for COVID-19. Eur Respir J 2020;55:2000688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Clark A, Jit M, Warren-Gash C et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of the population at increased risk of severe COVID-19 due to underlying health conditions in 2020: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e1003–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hussain A, Bhowmik B, do Vale Moreira NC. COVID-19 and diabetes: knowledge in progress. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2020;162:108142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cheng Y, Luo R, Wang K et al. Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int 2020;97:829–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ji HL, Zhao R, Matalon S, Matthay MA. Elevated plasmin(ogen) as a common risk factor for COVID-19 susceptibility. Physiol Rev 2020;100:1065–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Xu J, Yang X, Yang L et al. Clinical course and predictors of 60-day mortality in 239 critically ill patients with COVID-19: a multicenter retrospective study from Wuhan. Crit Care 2020;24:394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Murthy S, Gomersall CD, Fowler RA. Care for critically ill patients with COVID-19. JAMA 2020;323:1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Barba EJR. México y el reto de las enfermedades crónicas no transmisibles. El laboratorio también juega un papel importante. Rev Mex Patol Clin Med Lab 2018;65:4–17. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cordova-Villalobos J Ángel et al. Las enfermedades crónicas no transmisibles en México: sinopsis epidemiológica y prevención integral. Salud Pública Méx 2008;50:419–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Anderson P, Gual A, Colon J, Alcohol y atención primaria de la salud: informaciones clínicas básicas para la identificación y el manejo de riesgos y problemas Washington, DC: OPS, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pallarés Carratalá V, Górriz-Zambrano C, Morillas Ariño C, Llisterri Caro JL, Gorriz JL. COVID-19 and cardiovascular and kidney disease: where are we? Where are we going? Semergen 2020;46(Suppl 1):78–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hodgson K, Morris J, Bridson T, Govan B, Rush C, Ketheesan N. Immunological mechanisms contributing to the double burden of diabetes and intracellular bacterial infections. Immunology 2015;144:171–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Grupo de Colaboración de la Encuesta Mundial de Tabaquismo en Adultos. Preguntas sobre el tabaco destinadas a encuestas: Serie de preguntas básicas de la Encuesta Mundial sobre Tabaquismo en Adultos (GATS), 2nd edn. Atlanta, GA: Centros para el Control y la Prevención de Enfermedades de los Estados Unidos de América, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gómez-Dantes SS, Becerril VM, Knaul FM, Arreola H, Frenk J. The health system of Mexico. Salud Publica Mex 2011;53(Suppl 2):S220–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bringas HHH. Mortalidad por COVID-19 en Mexico: notas preliminares para un perfil sociodemográfico. Notas Coyuntura Del CRIM UNAM 2020;36. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.