Abstract

Background: Spain has one of the highest incidences of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) worldwide, so Spanish health care workers (HCW) are at high risk of exposure. Our objective was to determine severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) antibody seroprevalence amongst HCW and factors associated with seropositivity. Methods: A cross-sectional study evaluating 6190 workers (97.8% of the total workforce of a healthcare-system of 17 hospitals across four regions in Spain) was carried out between April and June 2020, by measuring immunoglobulin G (IgG)-SARS-CoV-2 antibody titres and related clinical data. Exposure risk was categorized as high (clinical environment; prolonged/direct contact with patients), moderate (clinical environment; non-intense/no patient contact) and low (non-clinical environment). Results: A total of 6038 employees (mean age 43.8 years; 71% female) were included in the final analysis. A total of 662 (11.0%) were seropositive for IgG against SARS-CoV-2 (39.4% asymptomatic). Adding available PCR-testing, 713 (11.8%) employees showed evidence of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, before antibody testing, 482 of them (67%) had no previous diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2-infection. Seroprevalence was higher in high- and moderate-risk exposure (12.1 and 11.4%, respectively) compared with low-grade risk subjects (7.2%), and in Madrid (13.8%) compared with Barcelona (7.6%) and Coruña (2.0%). High-risk [odds ratio (OR): 2.06; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.63–2.62] and moderate-risk (OR: 1.77; 95% CI: 1.32–2.37) exposures were associated with positive IgG-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies after adjusting for region, age and sex. Higher antibody titres were observed in moderate–severe disease (median antibody-titre: 13.7 AU/mL) compared with mild (6.4 AU/mL) and asymptomatic (5.1 AU/mL) infection, and also in older (>60 years: 11.8 AU/mL) compared with younger (<30 years: 4.2 AU/mL) people. Conclusions: Seroprevalence of IgG-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in HCW is a little higher than in the general population and varies depending on regional COVID-19 incidence. The high rates of subclinical and previously undiagnosed infection observed in this study reinforce the utility of antibody screening. An occupational risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection related to working in a clinical environment was demonstrated in this HCW cohort.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, seroprevalence, healthcare workers

Key Messages

Evaluating SARS-CoV-2-IgG antibodies in all the hospital personnel (>6000 subjects) of a Spanish multiregional healthcare system we have found a seroprevalence of 11.0% in health care workers (HCW), a little higher than in the general population and with a very variable percentage depending on the regional COVID-19 incidence.

Almost 40% of the hospital personnel with SARS-CoV-2 infection had a subclinical infection and 67% of HCW with SARS-CoV-2 infection had not been previously diagnosed before serological testing.

Seroprevalence was higher in high- and moderate-risk exposure, and both conditions were independent factors associated with anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG seropositivity.

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), first detected in Wuhan, China, in December 20191 has rapidly spread around the world, leading to an unprecedented burden on health care systems, causing over >60 million cases of confirmed infection and >1 million deaths worldwide by November 2020.2 In this setting, evaluating the seroprevalence of immunoglobulin G (IgG) against SARS-CoV2 amongst healthcare workers (HCW) is a very useful tool in order to understand the true rates of infection and identify asymptomatic infection.3

HCW have been shown to be at increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection due to occupational exposure to infected patients with an estimated prevalence by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing ranging from 1 to 20%, depending on the timeframe of the pandemic (early vs afterwards).4 Specifically, in Spain 40 961 cases of COVID-19 in HCW have been reported as of 29 May 2020, representing a staggering 24% of the total cases.5

Various reports have studied the antibody response in HCW with variable rates, depending on the country, the time when the analysis was performed, symptomatic status and employee category. Rates of seroprevalence amongst HCW range from 0.7% in a study evaluating half the staff during the acute phase in Italy6 to 44.7% in a study carried out in England during April–June 2020 which included symptomatic HCW.7 To the best of our knowledge, to date none of these studies has evaluated the whole population of workers belonging to a chain of hospitals with multiple hospitals in different regions of a country.

In this context, we conducted the present study which aims to study the seroprevalence of IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in all 6300 workers of HM Hospitals, a chain of 17 Hospitals in Spain across the regions of Madrid, Catalonia, Galicia and Castilla Leon, to assess the rate of symptomatic and asymptomatic infection. Furthermore, we analyzed different variables including professional exposure, epidemiological and clinical data, to study potential factors which may be involved in explaining the rates of infection in the workforce of this Spanish multicenter healthcare provider group.

Methods

Study design, population, setting and procedures

A cross-sectional study, measuring serum IgG anti-SARS-CoV-2 titres among all employees of the HM Group (GHM) was carried out. GHM treated over 15 000 patients during the period of March–May 2020 with >3000 COVID-19 inpatients. The total number of employees of the group is 6330.

We recruited participants via the HM Occupational Health Department. All employees registered at GHM were invited to participate in the study via email. A total of 6190 workers agreed to participate (97.8% of the total workforce). Participants were evaluated between 15 April and 30 June 2020, by measuring SARS-CoV-2 antibody titres and completing a face-to-face or online survey about clinical data (exposure grade, symptoms, diagnostic tests and therapy) related to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

We cross-referenced data with the regularly updated Health & Safety-Human Resources database. The occupational roles of staff were categorized into three groups of risk for SARS-CoV-2 exposure, considering professional category and working area: high risk exposure, including those workers who carry out their activity in a clinical environment and have prolonged direct contact with patients (e.g. nurse, doctor, physiotherapist, porter, etc.); moderate risk exposure, including those who work in a clinical environment and have non-intense/no patient contact, but are potentially at higher risk of nosocomial exposure (e.g. domestic and laboratory staff); and low risk exposure, which included those staff who work in a non-clinical environment and have minimal/no patient contact (e.g. office staff/administrative, information technology, secretarial, clerical).

Quantification of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2

We used the indirect chemiluminescence immunoassay MAGLUMI 2019-nCoV IgG (CLIA) developed by Snibe Diagnostic to measure IgG antibody titres against SARS-CoV-2. This serum test has a clinical sensitivity of 91.21% and a specificity of 97.33% (272 2019-nCoV IgG-en-EU, V1.2, 2020–02). Serum IgG titres were considered negative (non-reactive) with a result <0.900 AU/mL, positive (reactive) with a result ≥1.10 AU/mL and indeterminate with a result in the interval between 0.900 and 1.100 (0.900≤x < 1.10 ) AU/mL. Participants with indeterminate antibody titres were invited to return to repeat the serum titre test at least 7 days after the initial antibody test.

Based on clinical and serological data, patients were classified as either having: (i) no SARS-CoV-2 infection, which included participants with a negative serological test result (and a negative PCR when available), regardless of the previous presence of COVID-19-compatible symptoms; (ii) asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection, including individuals who did not report COVID-19-compatible symptoms and had a positive result in the serological test (and/or in PCR testing when available), or (iii) symptomatic infection, for those individuals who reported COVID-19 compatible symptoms and in whom SARS-CoV-2 infection was well documented either by a positive PCR test detecting RNA in oro/nasopharyngeal swabs and/or a positive serological result. This category was further classified into mild disease, as defined by patients who did not require hospital admission or emergency department stay, or moderate to severe disease, for those patients who required hospital admission or stay at the emergency department for assessment beyond the initial assessment in the occupational health centre or corresponding primary care centre.

PCR testing was performed only in subjects with COVID-19-compatible symptoms or in those asymptomatic but with close unprotected household or hospital contact with COVID-19 patients.

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics were performed as absolute and relative frequencies (%) for qualitative variables and as median and interquartile range for quantitative variables. Chi-squared tests were used to study the dependence between the presence or not of IgG antibodies against SARS-Cov-2 and age, sex, symptoms, infection category, grade of exposure to COVID-19 and region of hospital location. Differences in mean IgG titre between groups were analyzed by the Mann–Whitney U test, adjusting P values with the Bonferroni method for multiple comparisons. Univariate logistic regression was performed to study the association of the mentioned variables with the presence or not of IgG antibodies. Additionally, the association of exposure risk with the presence of IgG antibodies was analyzed adjusting for region, age and sex covariates.

All the statistical analyses have been conducted using R (version 4.0.2).

Results

Between 15 April and 30 June 2020, a total of 6190 employees were evaluated. Of those, 152 were excluded due to incomplete data, and 6038 were included in the final analysis.

Demographic and clinical data

The mean age of the analyzed participants was 43.8 years (SD 4.1; range 20–80 years) and 71.1% were females. Demographic and clinical characteristics for overall participants are summarized in Table 1. In total, 1253 participants (20.8%) reported COVID-19-compatible symptoms in the previous 2 months. Oro/nasopharyngeal PCR testing was performed in 1061 subjects (17.6%), with a positive result for SARS-CoV2 infection in 245 of these (23.1%). Among symptomatic participants, 96.4% were outpatients and 3.6% were admitted to hospital.

Table 1.

Geographical region, demographic characteristics, exposure grade, previous clinical data and final infection category among all participants (n = 6038), by IgG against SARS-CoV-2 results

| All (n = 6038) | Positive (n = 662) | Negative (n = 5349) | Indeterminate (n = 27) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Madrid | 3920 | 540 (13.8%) | 3363 (85.8%) | 17 (0.4%) |

| Coruña | 1099 | 22 (2.0%) | 1076 (97.9%) | 1 (0.1%) | |

| Barcelona | 887 | 67 (7.6%) | 820 (92.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Other | 132 | 33 (25.0%) | 90 (68.2%) | 9 (6.8%) | |

| Age, years | <30 | 909 | 112 (12.3%) | 785 (86.4%) | 12 (1.3%) |

| 30–45 | 2679 | 273 (10.2%) | 2395 (89.4%) | 11 (0.4%) | |

| 46–60 | 1881 | 209 (11.1%) | 1668 (88.7%) | 4 (0.2%) | |

| >60 | 569 | 68 (11.9%) | 501 (88.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Sex | Male | 1744 | 195 (11.2%) | 1542 (88.4%) | 7 (0.4%) |

| Female | 4294 | 467 (10.9%) | 3807 (88.7%) | 20 (0.5%) | |

| Exposure risk | Low-grade | 1238 | 89 (7.2%) | 1148 (92.7%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Moderate-grade | 1014 | 116 (11.4%) | 881 (86.9%) | 17 (1.7%) | |

| High-grade | 3786 | 457 (12.1%) | 3320 (87.7%) | 9 (0.2%) | |

| COVID-19 Symptoms | Yes | 1253 | 401 (32.0%) | 839 (67.0%) | 13 (1.0%) |

| Fever | 318 | 174 (54.7%) | 140 (44.0%) | 4 (1.3%) | |

| Low-grade fever | 342 | 166 (48.5%) | 171 (50.0%) | 5 (1.5%) | |

| Cough | 543 | 227 (41.8%) | 308 (56.7%) | 8 (1.5%) | |

| Breathlessness | 180 | 86 (47.8%) | 93 (51.7%) | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Anosmia | 208 | 161 (77.4%) | 41 (19.7%) | 6 (2.9%) | |

| Dysgeusia | 194 | 150 (77.3%) | 40 (20.6%) | 4 (2.1%) | |

| Diarrhoea | 277 | 126 (45.5%) | 149 (53.8%) | 2 (0.7%) | |

| PCR testinga | Non-testing | 4977 | 362 (7.3%) | 4595 (92.3%) | 20 (0.4%) |

| Positive | 245 | 194 (79.2%) | 49 (20.0%) | 2 (0.8%) | |

| Negative | 816 | 106 (13.0%) | 705 (86.4%) | 5 (0.6%) | |

| Infection category | No infection | 5300 | 0 (0.0%) | 5300 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Asymptomatic infection | 264 | 261 (98.9%) | 2 (0.8%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

| Mild | 395 | 351 (88.9%) | 43 (10.9%) | 1 (0.3%) | |

| Moderate–severe | 54 | 50 (92.6%) | 4 (7.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| NAb | 25 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 25 (100.0%) |

PCR testing was performed (prior to serological testing) in 1061 subjects: 763 subjects with COVID-19-compatible symptoms and 298 asymptomatic subjects with close unprotected household or hospital contact with COVID-19 patients.

NA, not applicable: subjects with indeterminate IgG result and negative or non-tested PCR.

Data of SARS-CoV-2 infection

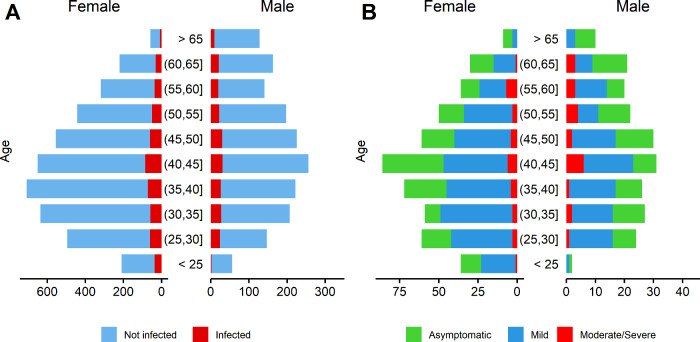

A total of 662 (11.0%) were seropositive for IgG against SARS-CoV-2. Among them, 261 (39.4%) were asymptomatic, which implies a seroprevalence of asymptomatic infection of 4.32%. Adding available PCR testing to serological data, 713 (11.8%) employees had evidence of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection (37.0% of them were asymptomatic). Table 2 shows the different infection categories according to the presence of COVID-19-compatible symptoms, PCR and IgG antibodies result. Figure 1 shows the distribution of infected subjects considering age, sex and infection category and severity. Among infected employees, 264 (37.0%) were asymptomatic. Among the 449 symptomatic subjects, 395 (88.0%) had mild symptoms, whereas 54 (12.0%) presented moderate to severe symptoms, and 45 (10%) required hospital admission. Among all the employees with SARS-CoV-2 infection documented after antibody testing, 482 (67.6%) had not previously received a diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Table 2.

Categories of SARS-CoV-2 infection (n = 713) based on the presence of COVID-19-compatible symptoms (symptomatic and asymptomatic) and the results of PCR (when availablea) and IgG SARS-CoV-2 tests

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Symptomatic | 449 | 63.0 |

| Symptoms + PCR positive + IgG positive | 175 | 24.5 |

| Symptoms + PCR positive (IgG negative or undetermined) | 48 | 6.7 |

| Symptoms + IgG positive (PCR negative or not tested) | 226 | 31.7 |

| Asymptomatic | 264 | 37.0 |

| No symptoms + PCR positive + IgG positive | 19 | 2.7 |

| No symptoms + PCR positive (IgG negative or undetermined) | 3 | 0.4 |

| No symptoms + IgG positive (PCR negative or not tested) | 242 | 33.9 |

PCR testing was performed (prior to serological test) in 1061 subjects: 763 subjects with COVID-19 compatible symptoms and 298 asymptomatic subjects with close unprotected household or hospital contact with COVID-19 patients.

Figure 1.

Distribution by age and sex among (A) infected hospital workers (n = 713) compared with the total hospital personnel (n = 6038) and (B) according to infection category among those infected. Infected subjects include both serology results and available PCR tests

Among the 662 seropositive participants, 401 (60.6%) reported previous COVID-19-compatible symptoms and 261 (39.4%) did not. Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics among all participants, by SARS-CoV-2 IgG serology result.

Risk factors associated with positive antibodies result

According to geographical regions, seroprevalence was 13.8% in Madrid, 7.6% in Barcelona (Catalonia) and 2.0% in Coruña (Galicia) (Chi-squared test, P < 0.0001). Regarding the exposure category, seroprevalence was 12.1% in high-grade risk exposure subjects, 11.4% in moderate-grade risk subjects and 7.2% in low-grade risk subjects. (Chi-squared test, P < 0.0001).

The univariate model (Table 3) identified moderate and high-risk exposure [odds ratio (OR): 1.67; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.25–2.23; OR: 1.77; 95% CI: 1.41–2.26, respectively) and the presence of COVID-19-compatible symptoms (OR: 8.16; 95% CI: 6.87–9.70) as variables associated with a positive result for IgG SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. Among the COVID-19-compatible symptoms, anosmia (OR: 36.44; 95% CI: 26.21–51.57), dysgeusia (OR: 35.50; 95% CI: 25.29–50.81), fever (OR: 12.95; 95% CI: 10.20–16.48) and low-grade fever (OR: 9.89; 95% CI: 7.85–12.46) showed the strongest correlation with the presence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies.

Table 3.

Results of univariate and multivariate logistic regression models for the identification of associated and independently associated factors with a positive result for IgG against SARS-CoV-2

| Univariate model | Multivariate model | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Region | Madrid | 1.000 (ref.) | 1.00 (ref.) |

| Barcelona | 0.51 (0.39–0.66) | 0.52 (0.40–0.66) | |

| Coruña | 0.13 (0.08–0.19) | 0.12 (0.08–0.18) | |

| Other | 2.09 (1.37–3.09) | 2.28 (1.51–3.37) | |

| Age, years | <30 | 1.000 (ref.) | 1.00 (ref.) |

| 30–45 | 0.80 (0.64–1.01) | 0.84 (0.67–1.06) | |

| 46–60 | 0.83 (0.66–1.06) | 0.96 (0.76–1.23) | |

| >60 | 0.88 (0.64–1.21) | 1.07 (0.77–1.48) | |

| Sex | Female | 1.000 (ref.) | 1.00 (ref.) |

| Male | 1.03 (0.86–1.23) | 1.02 (0.85–1.21) | |

| Exposure Risk | Low-grade | 1.000 (ref.) | 1.00 (ref.) |

| Moderate-grade | 1.67 (1.25–2.23) | 1.77 (1.32–2.37) | |

| High-grade | 1.77 (1.41–2.26) | 2.06 (1.63–2.62) | |

| COVID-19 Symptoms | No | 1.000 (ref.) | |

| Yes | 8.16 (6.87–9.70) | ||

| Fever | No | 1.000 (ref.) | |

| Yes | 12.95 (10.20–16.48) | ||

| Low-grade fever | No | 1.000 (ref.) | |

| Yes | 9.89 (7.85–12.46) | ||

| Cough | No | 1.000 (ref.) | |

| Yes | 8.36 (6.86–10.17) | ||

| Breathlessness | No | 1.000 (ref.) | |

| Yes | 8.39 (6.18–11.38) | ||

| Anosmia | No | 1.000 (ref.) | |

| Yes | 36.44 (26.21–51.57) | ||

| Dysgeusia | No | 1.000 (ref.) | |

| Yes | 35.50 (25.29–50.81) | ||

| Diarrhea | No | 1.000 (ref.) | |

| Yes | 8.08 (6.27–10.39) | ||

| Infection category | Mild | 1.00 (ref.) | |

| Moderate–severe | 1.57 (0.60–5.37) |

We built a multivariate logistic regression model to adjust for age, sex and region for association between exposure risk and SARS-CoV-2 infection. The results showed no change in the association for moderate and high-risk exposure (OR: 1.77; 95% CI: 1.32–2.37; OR: 2.06; 95% CI: 1.63–2.62 respectively), nor for the adjusting variables (see Table 3).

Antibody titres

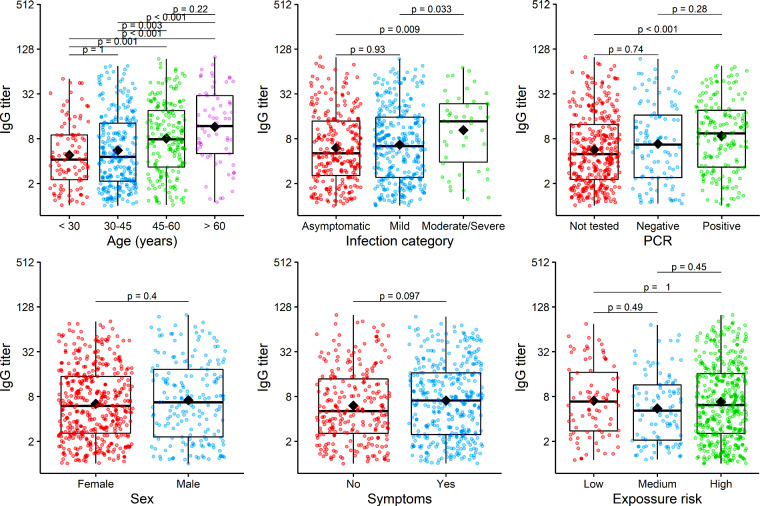

Figure 2 shows the distribution of antibody titres considering demographics, clinical characteristics and grade of exposure. Higher titres were observed in patients with moderate–severe disease [median antibody titre of 13.7 (3.9––23.6) AU/mL] compared with patients with mild symptoms [median titre 6.4 (2.4–15.6) AU/mL] and subjects with asymptomatic infection [median titre 5.1 (2.6 – 13.8) AU/mL]. Considering age, higher titres were also observed in subjects aged >60 years and between 46 and 60 years [median antibody titre 11.8 (5.0–30.2) and 7.9 (3.3–19.1) AU/mL, respectively] compared with younger people [median 4.6 (2.1–12.9] between 30–45 years and 4.2 (2.2––9.0) in those <30 years].

Figure 2.

Boxplots of the IgG titre of the IgG-positive subjects grouped by different baseline variables: age, infection category, SARS-Cov-2 PCR result, sex, COVID-19 symptoms and exposure to COVID-19. Black diamonds represent the mean of IgG titre. The IgG titre value of all subjects are presented as jittered points by the grouping variable to help visualization. Mean differences were evaluated by Mann–Whitney U test and P values adjusted by Bonferroni method for multiple tests.

Discussion

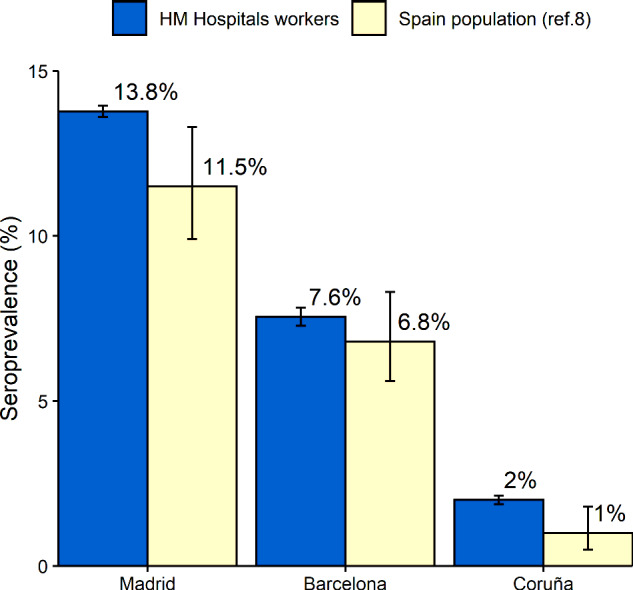

The present study evaluated, with a systematic screening for antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, a large cohort of >6000 health service employees of a tertiary institution spread over several regions of Spain, a country severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The results show a relatively high prevalence of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection in HCW. The seroprevalence of IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in HCW in this study was 11%, with highly variable regional percentages. According to regions, HCW seroprevalence has been slightly higher compared with the general population in Spain (Figure 3), where the figures have been similar to those of other countries.8–11

Figure 3.

Seroprevalence of IgG against SARS-CoV-2 in Madrid, Barcelona (Catalonia) and Coruña (Galicia) in HM Hospital workers compared with the estimated seroprevalence in the same regions in a national study estimating seroprevalence in the general population;8 Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals

Several studies estimating the seroprevalence in HCW have been published recently. However, only a few of them have evaluated large cohorts (with >1000 participants) of health staff and they have reported highly variable rates of HCW global seroprevalence, mainly depending on the region, the percentage and the characteristics of the health personnel analyzed. Thus, the reported overall seroprevalence in HCW has been shown to be 18% in London, UK, evaluating 93% of symptomatic and only 8% of asymptomatic employees;7 13.7% in New York City, USA, evaluating 56% of the health personnel;12 and 1.8% in China in a study evaluating individuals from four different geographic locations and different populations (25% of them HCW).10 The only report with a large cohort evaluating all the health personnel of a single region has shown a seroprevalence of 4% in HCW of the central region of Denmark,13 a country with much lower prevalence of COVID-19.

Our study demonstrates the importance of the degree of exposure to COVID-19 patients, with higher seroprevalence in frontline healthcare personnel compared with personnel working in a non-clinical environment. In our cohort, workers in any clinical environment, not only at high-risk but also at moderate-risk of exposure, presented a higher probability of seropositivity compared with those workers with no exposure to clinical environments (OR: 2.06; 95% CI: 1.63–2.62 for high-risk exposure; and OR: 1.77; 95% CI: 1.32–2.37 for moderate-risk exposure). This observation is consistent with results reported in other studies.13–15 However, it contrasts with reports from China and Europe in which no differences were observed when comparing HCW from high-risk areas (involved in close contact with COVID-19 patients) with personnel without direct contact with patients, both in the detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection by PCR16–19 and by the presence of antibodies.20,21 In this context, we think our methodology is more appropriate to evaluate this point, since we have evaluated the presence of SARS-CoV-2 infection by detecting antibodies (which is more accessible than PCR testing for detecting asymptomatic infection) in all of the employees (avoiding possible selection bias) of a large cohort of participants.

In our cohort, >65% of the subjects with SARS-CoV-2 infection had not been diagnosed previously by serological evaluation, highlighting the great value of testing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, especially in identifying undetected infections in HCW. Seropositivity includes both symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. It is well known that a substantial percentage of all infections are asymptomatic and that infected subjects can carry the virus without presenting any symptoms for several weeks. In the current study, up to 39.4% of the HCW presenting with antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 were completely asymptomatic, not reporting any COVID-19-compatible symptoms at interview. This high rate of subclinical infection in HCW is crucial, since asymptomatic workers may potentially spread the SARS-CoV-2 infection both in a clinical environment with patients and other HCW, and well as in their households.22 It is interesting to point out that the quantitative analysis of antibodies showed lower titres in asymptomatic individuals compared with moderate-to-severe COVID-19 patients, suggesting that asymptomatic infection generates a weaker immune response against SARS-CoV-2.23 Inversely, and with respect to the severity of the disease, higher titres of IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 were observed in patients with moderate–severe disease compared with those with mild symptoms. In our study, 12% of the symptomatic HCW with documented SARS-CoV-2 infection had moderate to severe disease (requiring hospital admission or a stay at the emergency department), and, specifically, 10% were admitted to hospital; these are similar figures to reported data in HCW in Spain (10 % admitted to hospital, with a lethality rate of 0.1%).5 In this context, the finding of higher IgG titres seems to indicate a greater severity of the disease.

In our cohort, among COVID-19-compatible symptoms the most strongly associated with seropositivity were loss of smell and taste, fever and low-grade fever. Our findings are consistent with the Danish HCW cohort, where loss of taste or smell was the symptom most strongly associated with a positive antibody response.13 However, other symptoms such as cough and dyspnea, of important clinical relevance, showed less association with seropositivity. This observation highlights the importance of always including the presence of anosmia and dysgeusia in the clinical questionnaire, symptoms of probable greater specificity, although with less impact on the clinical prognosis.

Regional differences reported in a large nationwide study of seroprevalence may explain in part our results (Figure 3 and Supplementary Map, available as Supplementary data at IJE online). Madrid has been one of the regions of Spain with the highest incidence of COVID-19 cases and presented a seroprevalence rate of 11.5% (95% CI: 9.9–13.3%) in the total population,8 compared with 13.8% (95% CI: 13.6–13.9%) in HCW in the present study. Coruña (Galicia), in contrast, is one of the regions less affected by the pandemic, with a general seroprevalence rate of 1.0% (95% CI: 0.5–1.8%) and 2.0% (95% CI: 1.9–2.1%) in the current study. Barcelona (Catalonia) showed a rate of 6.8% (95% CI: 5.6–8.3%) in the national seroprevalence study and we found a seroprevalence of 7.6% (95% CI: 7.3–7.8%).8 These results show that the higher the incidence of COVID-19 in a region (and the more affected is its health system), the greater the seroprevalence in its HCW. However, this finding has not been published in Europe, whereas a recent study evaluating SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in a sample of frontline HCW in 12 US states is not conclusive on this point.24 A simple explanation for the higher risk of infection in HCW in high-incidence areas is that they come into more contact with COVID-19 patients. Supporting this explanation, limited cohorts have described as other risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection in HCW longer duty hours and suboptimal hand hygiene after contact with COVID-19 patients.25 This has been especially important in the early stages of the pandemic, when protective measures for health workers were less known, trained and available.

The main differences between our HCW cohort and the general population seroprevalence study could be found in sex and age. Although sex proportion is different (ratio female:male of 1:1 in the general population study and 2.3:1 in our HCW cohort), no differences in seroprevalence by sex were found in both studies. Regarding age, the subgroup of 30–60 year olds (in which a slightly higher seroprevalence was documented in the nationwide study; 30–60 years: 4.8% vs overall: 4.6%) is overrepresented in our HCW cohort compared with the Spanish general population study (75.5% vs 49.6%, respectively).8 Therefore, we can assume that differences in distribution on age (but not on sex) could be partially responsible for the differences in seroprevalence observed between both studies.

Furthermore, the correlation of HCW seropositivity with regional seropositivity might be largely explained by contact and transmission outside the workplace. Therefore, overall, hospital personnel would not be at excessively higher risk compared with the general population. However, the risk within HCW is strongly associated with risky professions, explaining why HCW at high and moderate risk of exposure (with activity in a clinical environment) have higher seroprevalence.

With respect to age, we observed a higher titre of IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in older subjects compared with younger HCW. This could be partially explained by the fact that susceptibility to symptomatic and severe infection seems to increase with age.26 In this sense, although susceptibility to infection is probably similar among different age groups, more symptomatic and severe infection usually implies a more intensive antibody response.

The current study has important limitations that need to be mentioned. Measuring humoral response to detect previous SARS-CoV-2 infection has been debated. The prevalence could have been underestimated because at the time of collection some participants had either been recently infected and had not yet developed an IgG response, or had previously been infected but antibody levels had subsequently declined. Other limitations are the incomplete PCR data (only performed in 17.6% of the subjects), the lack of accurate data on the timing of symptoms relative to testing, and the lack of data on the participation of individuals in high-risk procedures, like intubation and bronchoscopy, or other extra-professional risk behaviours, like public transport use or participation in large gatherings. Finally, when comparing our regional HCW seroprevalence with regional seroprevalence in the general population, we have to state that our study took some samples up to 1 month later than the national seroprevalence study. However, both studies began on similar dates and at that time the spread of the virus in Spain was at its lowest level, therefore it is very unlikely that the observed differences were due to the fact that some samples in our study were obtained slightly later.

Conclusion

We have found a slightly higher seroprevalence of IgG SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in HCW as compared with the general population, with very variable percentage depending on the region, correlating with community COVID-19 incidence. Almost 40% of the HCW with antibody response were asymptomatic and two-thirds of the HCW with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection had not been previously diagnosed before antibody testing. Moreover, we found a clear occupational risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection related to working in a clinical environment.

Ethics approval

The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of HM Group (GHM) (Comité Ético de Investigación con Medicamentos de HM Hospitales) (ref. no. 20.04.1611/1640-GHM).

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at IJE online.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

All authors conceptualized and designed the study, J.F.V., R.M and J.M.C.V. drafted the manuscript and made final revisions, and all authors critically revised, read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1708–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

- 3. Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, Takwoingi Y et al. Antibody tests for identification of current and past infection with SARS-CoV-2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;6:CD013652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chou R, Dana T, Buckley DI, Selph S, Fu R, Totten AM. Epidemiology of and Risk Factors for Coronavirus Infection in Health Care Workers: A Living Rapid Review. Ann Intern Med 2020;173:120–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Análisis de los casos de COVID-19 en personal sanitario notificados a la red nacional de vigilancia epidemiológica (RENAVE) hasta el 10 de mayo en España. Informe a 29 de mayo de 2020. Equipo Covid-19. RENAVE. Centro Nacional de Epidemiología CNM. Instituto de Salud Carlos III. https://www.isciii.es/QueHacemos/Servicios/VigilanciaSaludPublicaRENAVE/EnfermedadesTransmisibles/Documents/INFORMES/Informes%20COVID-19/COVID-19%20en%20personal%20sanitario%2029%20de%20mayo%20de%202020.pdf

- 6. Lahner E, Dilaghi E, Prestigiacomo C et al. Prevalence of Sars-COV-2 infection in health workers (HWs) and diagnostic test performance: the experience of a teaching hospital in central Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pallett SJC, Rayment M, Patel A et al. Point-of-care serological assays for delayed SARS-CoV-2 case identification among health-care workers in the UK: a prospective multicentre cohort study [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jul 24]. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:885–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pollán M, Pérez-Gómez B, Pastor-Barriuso R et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Spain (ENE-COVID): a nationwide, population-based seroepidemiological study. Lancet 2020;396:535–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sood N, Simon P, Ebner P et al. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies among adults in Los Angeles County, California, on April 10-11, 2020. JAMA 2020;323:2425–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xu X, Sun J, Nie S et al. Seroprevalence of immunoglobulin M and G antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in China. Nat Med 2020;26:1193–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stringhini S, Wisniak A, Piumatti G et al. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in Geneva, Switzerland (SEROCoV-POP): a population-based study. Lancet 2020;396:313–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moscola J, Sembajwe G, Jarrett M; Northwell Health COVID-19 Research Consortium et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies in Health Care Personnel in the New York City Area. JAMA 2020;324:893–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Iversen K, Bundgaard H, Hasselbalch RB et al. Risk of COVID-19 in health-care workers in Denmark: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20:1401–08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grant J, Wilmore S, McCann N et al. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in healthcare workers at a London NHS Trust. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2020; Aug 4; 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Garcia-Basteiro AL, Moncunill G, Tortajada M et al. Seroprevalence of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 among health care workers in a large Spanish reference hospital. Nat Commun 2020;11:3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lai X, Wang M, Qin C et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-2019) infection among health care workers and implications for prevention measures in a tertiary hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e209666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kluytmans-van den Bergh MFQ, Buiting AGM, Pas SD et al. Prevalence and clinical presentation of health care workers with symptoms of coronavirus disease 2019 in 2 Dutch Hospitals during an early phase of the pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e209673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hunter E, Price DA, Murphy E et al. First experience of COVID-19 screening of health-care workers in England. Lancet 2020;395:e77–e78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Folgueira MD, Muñoz-Ruipérez C, Alonso-López MA, Delgado R. SARS-CoV-2 infection in health care workers in a large public hospital in Madrid, Spain, during March 2020. medRxiv, 27 April 2020, preprint: not peer reviewed. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hunter B R Dbeibo L Weaver C S et al. Seroprevalence of severe acute respiratory coronavirus virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) antibodies among healthcare workers with differing levels of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patient exposure. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2020;41:1441–2. 10.1017/ice.2020.390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dimcheff DE, Schildhouse RJ, Hausman MS et al. Seroprevalence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection among Veterans Affairs healthcare system employees suggests higher risk of infection when exposed to SARS-CoV-2 outside of the work environment. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2020; Sep 23; 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rivett L, Sridhar S, Sparkes D; The CITIID-NIHR COVID-19 BioResource Collaboration et al. Screening of healthcare workers for SARS-CoV-2 highlights the role of asymptomatic carriage in COVID-19 transmission. Elife 2020;9:e58728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Long QX, Tang XJ, Shi QL et al. Clinical and immunological assessment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat Med 2020;26:1200–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Self WH, Tenforde MW, Stubblefield WB; CDC COVID-19 Response Team et al. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 among frontline health care personnel in a multistate hospital network - 13 academic medical centers, April-June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1221–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ran L, Chen X, Wang Y, Wu W, Zhang L, Tan X. Risk factors of healthcare workers with Corona Virus disease 2019: a retrospective cohort study in a designated hospital of Wuhan in China. Clin Infect Dis 2020;71:2218–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kang SJ, Jung SI. Age-related morbidity and mortality among patients with COVID-19. Infect Chemother 2020;52:154–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.