Abstract

Introduction

Care home residents are at high risk of dying from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Regular testing, producing rapid and reliable results is important in this population because infections spread quickly, and presentations are often atypical or asymptomatic. This study evaluated current testing pathways in care homes to explore the role of point-of-care tests (POCTs).

Methods

A total of 10 staff from eight care homes, purposively sampled to reflect care organisational attributes that influence outbreak severity, underwent a semi-structured remote videoconference interview. Transcripts were analysed using process mapping tools and framework analysis focussing on perceptions about, gaps within and needs arising from current pathways.

Results

Four main steps were identified in testing: infection prevention, preparatory steps, swabbing procedure and management of residents. Infection prevention was particularly challenging for mobile residents with cognitive impairment. Swabbing and preparatory steps were resource-intensive, requiring additional staff resource. Swabbing required flexibility and staff who were familiar to the resident. Frequent approaches to residents were needed to ensure they would participate at a suitable time. After-test management varied between sites. Several homes reported deviating from government guidance to take more cautious approaches, which they perceived to be more robust.

Conclusion

Swab-based testing is organisationally complex and resource-intensive in care homes. It needs to be flexible to meet the needs of residents and provide care homes with rapid information to support care decisions. POCT could help address gaps but the complexity of the setting means that each technology must be evaluated in context before widespread adoption in care homes.

Keywords: care homes, COVID-19, point-of-care testing, diagnosis, older people

Key Points

Testing for COVID-19 in care homes is complex and could require reconfiguration of staffing and environment.

Isolation and testing procedures are challenging when providing person-centred care to people with dementia.

Point-of-care testing results could give care homes greater flexibility to test in person-centredways.

There was evidence that care home staff interprets testing guidance, rather than follow it verbatim.

Each POCT must be evaluated in the context of care homes to understand its effect on care home processes.

Introduction

Around 430,000 people in England and Wales live in care homes [1]. The majority of care home residents are older, affected by prevalent multimorbidity, activity limitation and cognitive impairment [2]. In the first 6 months of 2020, there were 29,393 excess deaths in care homes in England and Wales, with 19,394 attributed to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [3].

Once a COVID-19 outbreak starts, the virus can spread rapidly through a care home. Presentations in residents are often atypical or asymptomatic. A study of 394 residents of four London care homes conducted in April 2020 [4] found 33% of residents with COVID-19 were asymptomatic. A further 31% had symptoms commonly seen in acute frailty syndromes including delirium, postural instability and diarrhoea. European guidance [5] explains that the high prevalence of asymptomatic or atypical presentations means that testing for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in respiratory secretions is central to COVID-19 management. Several testing strategies have been used for residents and staff during the pandemic in the UK: an initial strategy of testing symptomatic residents only [6] progressed to a programme of 28-day and 7-day regular surveillance testing of residents and staff, respectively [7]. Testing uses nasopharyngeal swabs which are sent for laboratory-based Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR). Frequent changes to testing protocols in the first part of the pandemic led to uncertainty as care homes had to readapt swabbing procedures and infection prevention measures multiple times, whilst the demands placed on the testing system by the rapid escalation of testing have led to delays with test results that compromise care homes’ ability to deliver effectivecare.

Rapid diagnostic point-of-care testing (POCT) could potentially address these challenges and ease pressure on care homes staff members. However, little is known about the most effective way to implement these tests into existing procedures and COVID-19 management.

In this paper, we describe an interview-based process mapping study undertaken to understand the complexity of implementing a comprehensive testing regime for COVID-19, given the fragmented landscape of care homes in England, and the consequent impact on staff time and workload. Gaps in the pathway and opportunities to utilise COVID-19 tests are also highlighted.

Methods

Between July and August 2020, care home staff members were contacted through a national online COVID-19 peer-support group for care home managers and staff [8] and then recruited to take part in semi-structured interviews. Purposive sampling was used to ensure the opinions elicited were representative of a range of organisational factors (care home size, residential/nursing, independent operator/chain) that have been shown to influence the severity of outbreaks during the pandemic [9]. Interview transcripts were analysed using process mapping tools to describe and visualise clinical pathways [10]. A detailed description of the research method can be found in Appendix I.

Results

A total of 10 staff members from eight care homes—with more than 5 years’ experience in the sector—accepted to take part in the study—Appendix I.

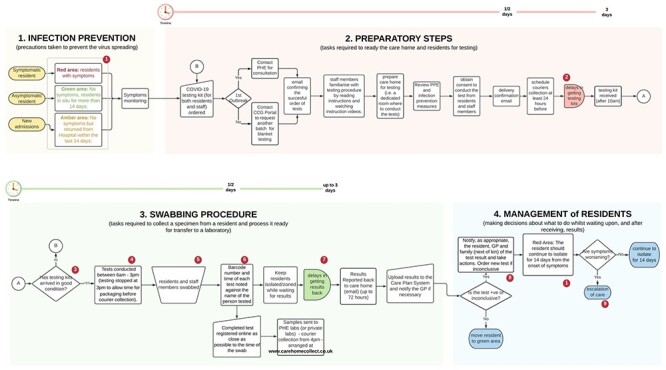

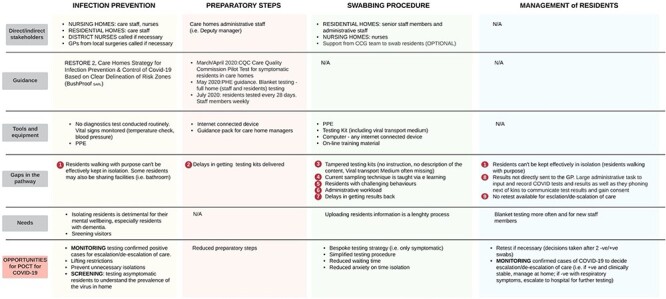

Testing for COVID-19 requires each care home to order testing kits, to swab residents, to upload each test barcodes to a dedicated portal and to ship samples to the laboratory via pre-arranged courier. Four main steps were identified in the COVID-19 testing and management pathway, illustrated as a process in Figure 1. Table 1 summarises key settings, environmental features and staff requirements involved in testing/managing for COVID-19. The core aspects are the nine gaps in the pathway that have hindered the efficient use of testing. Mitigation strategies and opportunities for POCT are presented in Appendix II.

Figure 1 .

Overall swabbing and management process of resident in care homes.

Table 1 .

Summary of relevant stakeholders, guidance, resources, gaps in the pathway, needs and opportunities forPOCT.

|

The four main steps were:

(1) Infection prevention: the allocation of residents to dedicated containment zones to prevent infections has become widespread in care homes during the pandemic [11]. Effective zoning depends upon recognising residents who are COVID-19 positive and moving them to a ‘red’ area. These are separate from ‘green’ areas, where COVID-19 negative residents receive care. A major challenge was supporting residents with dementia and those who ‘walk with purpose’ or ‘wander’ to understand and engage with infection prevention measures.

(2) Preparatory steps: sequential steps are mandatory to prepare care homes for swabbing (Figure 1). National guidance suggested two staff members should be involved—one to swab residents and one to record registration information. This had implications for staffing resource and rostering. A significant and persisting challenge was the need to do routine screening tests—weekly for staff and monthly for residents—alongside ad hoc testing for symptomatic residents. This was easier when the incidence of COVID-19 was low but became more challenging, from an organisational perspective, as incidence increased.

(3) Swabbing procedure: staff recognised that testing was daunting for residents, particularly those with dementia. Attention was given to ensuring that staff familiar to each resident was involved in swabbing. Flexibility was required, with staff often returning to residents more than once to test at a time which was acceptable, with implications for staff time. Staff was required to register the swab, once taken, by entering data on the online portal, a process considered cumbersome and time-consuming. These complex considerations had to be addressed under time pressure because the staff was given 72 h to complete each test from kit delivery.

(4) Management of residents: symptomatic residents were usually asked to remain in their rooms until a test result was available. This was not always possible with residents walking with purpose. Asymptomatic residents undergoing routine testing were not restricted in their movements. Test results were returned by email, then had to be communicated to residents, families and General Practitioners, and entered in care records. Some care homes interpreted government recommendations [12] differently: several respondents considered that retesting positive residents after quarantine would provide reassurance they were no longer infective. Others suggested that repeat testing should be done in residents where there was a high suspicion of COVID-19, therefore in isolation, when a negative test returned.

Discussion

These findings illustrate the complexity of the processes in testing care home residents for COVID-19. Infection prevention and testing processes are challenged by the individual needs of residents with dementia. Routine testing has staffing and organisational implications. Existing test registration systems place an administrative burden on staff. Current training materials are generic, with no face-to-face training and without considering complex organisational issues around testing. Also, nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swabs are unpleasant and alternative, less invasive processes (e.g. saliva testing) should be considered.

The variation in how guidance was interpreted by care homes, with consequential discrepancies in management approaches, illustrates the need for caution. Care home managers require a robust testing strategy to constantly monitor residents and to safeguard vulnerable people. Guidelines have not been adapted to the care home setting and, as a result, care home managers interpret them according to the needs of their unique care environment. Also, interpreting diagnostic test results requires nuanced consideration of sensitivity and specificity and how these are influenced by the prevalence of COVID-19 [13–15].

We identified several ways in which POCTs could help. They could reduce the administrative burden associated with requesting and registering tests and provide staff with greater flexibility to accommodate the needs of residents with dementia. The rapid results provided by POCTs could allow more efficient use of zoning to save residents from prolonged and unnecessary isolation and would better inform decisions about hospital admission. However, conducting a diagnostic test requires face-to-face training with professionals trained in competency assessment, test interpretation and risk assessment around testing kits and the environment in which they will be used. For instance, in November 2020 the UK Government has initiated a pilot test with rapid antigen-based lateral flow tests (LFTs) to support mass population testing and to open care homes to visitors [16]; an earlier assessment [17,18] has found a drop in sensitivity (48.89% positives detected out of all those with current viral infection according to laboratory testing) when these tests are conducted by self-trained members of the public. This is compared to 73% sensitivity when they are carried out by trained healthcare workers. Also, consideration needs to be given to how to help care homes staff interpret and respond to POCT results without introducing unacceptable variation in practice and what the role of clinicians in this process wouldbe.

Given the vulnerability of care home residents to COVID-19 and the scale of the outbreak in the first wave, our findings have great importance to inform future management of the pandemic in care homes and to share lessons learnt on COVID-19 diagnostic pathway in care homes, as advocated in recent studies [19]. There are examples of POCTs being deployed in a wide range of settings during the pandemic—such as airports [20] and universities [21,22]—without considering context-specific issues that might influence utility. The evidence presented here suggests that such an approach will not work in care homes due to the complexity of the processes involved and context-specific evaluation should be mandatory.

The main limitation of this study is the small number of interviews. The findings cannot be regarded as representative of all care homes. They are, however, sufficient to understand and illustrate the complexity of the testing pathway in care homes as a basis for future POCT research in this setting.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Massimo Micocci, NIHR London In Vitro Diagnostics Co-operative, London, UK.

Adam L Gordon, Division of Medical Sciences and Graduate Entry Medicine, University of Nottingham, UK; NIHR Applied Research Collaboration East Midlands (ARC-EM), Nottingham UK.

A Joy Allen, NIHR Newcastle In Vitro Diagnostics Co-operative, Newcastle University, UK.

Timothy Hicks, NIHR Newcastle In Vitro Diagnostics Co-operative, Newcastle University, UK; Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, UK.

Patrick Kierkegaard, NIHR London In Vitro Diagnostics Co-operative, London, UK.

Anna McLister, NIHR London In Vitro Diagnostics Co-operative, London, UK.

Simon Walne, NIHR London In Vitro Diagnostics Co-operative, London, UK.

Gail Hayward, NIHR Community Healthcare MedTech and IVD CO-operative, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Radcliffe Primary Care Building, Radcliffe Observatory Quarter, Woodstock Road, Oxford, OX2 6GG, UK.

Peter Buckle, NIHR London In Vitro Diagnostics Co-operative, London, UK.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank care home managers and staff members who took part in the study and members of the CONDOR platform for their comments: Prof Richard Body, Prof Daniel Lasserson, Dr Brian Nicholson, Dr David Ashley Price, Dr Charles Reynard, Ms Val Tate, Prof Mark Wilcox.

Authorship Statement

The CONDOR study team comprises partners from Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust’s Diagnostic and Technology Accelerator (DiTA), AHSN North East and North Cumbria (NENC), UK National Measurement Laboratory, University of Manchester, University of Nottingham, University of Oxford, Yorkshire and Humber AHSN, and NIHR MedTech and In Vitro Diagnostics Co-operatives (MICs) based in Oxford, Leeds, London and Newcastle.

Ethical Approval

This project was approved as a Service Evaluation by Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust (ICHNT)—registration no. 471.

Declaration of Sources of Funding

This work was supported by National Institute for Health Research NIHR, Asthma UK and the British Lung Foundation, as a part of the CONDOR study. MM, PK, AML, SW, and PB are supported by the NIHR London In Vitro Diagnostics Co-operative; ALG is funded in part by the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration-East Midlands (ARC-EM); AJA and TH are supported by the NIHR Newcastle In Vitro Diagnostics Co-operative, GH is supported by the NIHR Community Healthcare MedTech and IVD Co-operative. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funders, the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

References

- 1. Care Homes Market Study . Care Homes Market Study. London, 2017. https://www.gov.uk/cma-cases/care-homes-market-study(12 October 2020, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gordon AL, Franklin M, Bradshaw Let al. Health status of UK care home residents: a cohort study. Age Ageing 2014; 43: 97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Office of National Statistics . Deaths involving COVID-19 in the care sector, England and Wales: deaths occurring up to 12 June 2020 and registered up to 20 June 2020 (provisional). https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/a. (28 October 2020, date last accessed)

- 4. Graham NS, Junghans C, Downes Ret al. SARS-CoV-2 infection, clinical features and outcome of COVID-19 in United Kingdom nursing homes. J Infect 2020; 81: 411–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . Surveillance of COVID-19 at long- term care facilities in the EU/EEA. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/covid-19-long-term-care-facilities-surveillance-guidance.pdf(16 December 2020, date last accessed)

- 6. British Geriatrics Society . COVID-19: Managing the COVID-19 pandemic in care homes for older people. 2020. https://www.bgs.org.uk/resources/covid-19-managing-the-covid-19-pandemic-in-care-homes(12 October 2020, date last accessed)

- 7. Department of Health and Social Care . Whole Home Testing for care home staff and residents. https://www.local.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/Care%20home%20testing%20factsheet.pdf (24 January 2021, date last accessed).

- 8. Spilsbury K, Devi R, Griffiths Aet al. SEeking AnsweRs for Care Homes during the COVID-19 pandemic (COVID SEARCH). Age Ageing 2020; afaa201. 10.1093/ageing/afaa201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Department of Health and Social Care . Vivaldi 1: Coronavirus (COVID-19) care homes study report. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/vivaldi-1-coronavirus-covid-19-care-homes-study-report(12 October 2020, date last accessed)

- 10. Lim AJ, Village J, Salustri FAet al. Process mapping as a tool for participative integration of human factors into work system design. Eur J Ind Eng 2014; 8: 273–90. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bushproof . Care Homes Strategy for Infection Prevention & Control of Covid-19 Based on Clear Delineation of Risk Zones. https://www.bushproof.com/care-homes-strategy-for-infection-prevention-control-of-covid-19-based-on-clear-delineation-of-risk. (12 October 2020, date last accessed)

- 12. UK Department of Health and Social Care . Coronavirus (COVID-19): adult social care action plan. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-adult-social-care-action-plan(28 October 2020, date last accessed)

- 13. Altman DG, Bland JM. Statistics notes: diagnostic tests 2: predictive values. BMJ 1994; 309: 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fanshawe TR, Power M, Graziadio Set al. Interactive visualisation for interpreting diagnostic test accuracy study results. BMJ Evid-based Med 2018; 23: 13–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH, Sackett DL. Users' guides to the medical literature: III. How to use an article about a diagnostic test B. what are the results and will they help me in caring for my patients? JAMA 1994; 271: 703–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wise J. Covid-19: safety of lateral flow tests questioned after they are found to miss half of cases. BMJ 2020; 371: m4744. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4744(14 December 2020, date last accessed). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.PHE Porton Down & University of Oxford. Preliminary report from the Joint PHE Porton Down & University of Oxford SARS-CoV-2 test development and validation cell: Rapid evaluation of Lateral Flow Viral Antigen detection devices (LFDs) for mass community testing. https://www.ox.ac.uk/sites/files/oxford/media_wysiwyg/UK%20evaluation_PHE%20Porton%20Down%20%20University%20of%20Oxford_final.pdf(14 December 2020, date last accessed)

- 18. García-Fiñana M, Hughes D, Cheyne C, Burnside G, Buchan I. Calum Semple at University of Liverpool as part of NHS Cheshire and Merseyside CIPHA (Combined Intelligence for Population Health Action). Innova Lateral Flow SARS-CoV-2 Antigen test accuracy in Liverpool Pilot: preliminary data, 26 November 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/innova-lateral-flow-sars-cov-2-antigen-test-accuracy-in-liverpool-pilot-preliminary-data-26-november-2020(16 December 2020, date last accessed)

- 19. Spilsbury K, Devi R, Daffu-O’Reilly Aet al. University of Leeds. LESS COVID-19; Learning by Experience and Supporting the Care Home Sector during the COVID-19 pandemic: Key lessons learnt, so far, by frontline care home and NHS staff https://www.lumc.nl/sub/9600/att/LESSCOVIDUKNurseryhomes(16 December 2020, date last accessed)

- 20.Burridge T, BBC News. Covid-19: First UK airport coronavirus testing begins. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-54604100(28 October 2020, date last accessed)

- 21. Paltiel AD, Zheng A, Walensky RP. Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 screening strategies to permit the safe reopening of college campuses in the United States. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3: e2016818–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rauch JN, Valois E, Ponce-Rojas JCet al. Rapid CRISPR-based surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in asymptomatic college students captures the leading edge of a community-wide outbreak. medRxiv 2020. 10.1101/2020.08.06.20169771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.