Abstract

Tau oligomers have recently emerged as the principal toxic species in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and tauopathies. Tau oligomers are spontaneously self-assembled soluble tau proteins that are formed prior to fibrils, and they have been shown to play a central role in neuronal cell death and in the induction of neurodegeneration in animal models. As the therapeutic paradigm shifts to targeting toxic tau oligomers, this suggests the focus to study tau oligomerization in species that are less susceptible to fibrillization. While truncated and mutation containing tau as well as the isolated repeat domains are particularly prone to fibrillization, the wild-type (WT) tau proteins have been shown to be resistant to fibril formation in the absence of aggregation inducers. In this review, we will summarize and discuss the toxicity of WT tau both in vitro and in vivo, as well as its involvement in tau oligomerization and cell-to-cell propagation of pathology. Understanding the role of WT tau will enable more effective biomarker development and therapeutic discovery for treatment of AD and tauopathies.

Keywords: Tau accumulation and toxicity, Tau oligomers and aggregates, Conformational ensembles, Cell-to-cell propagation, Neurodegenerative diseases

Introduction

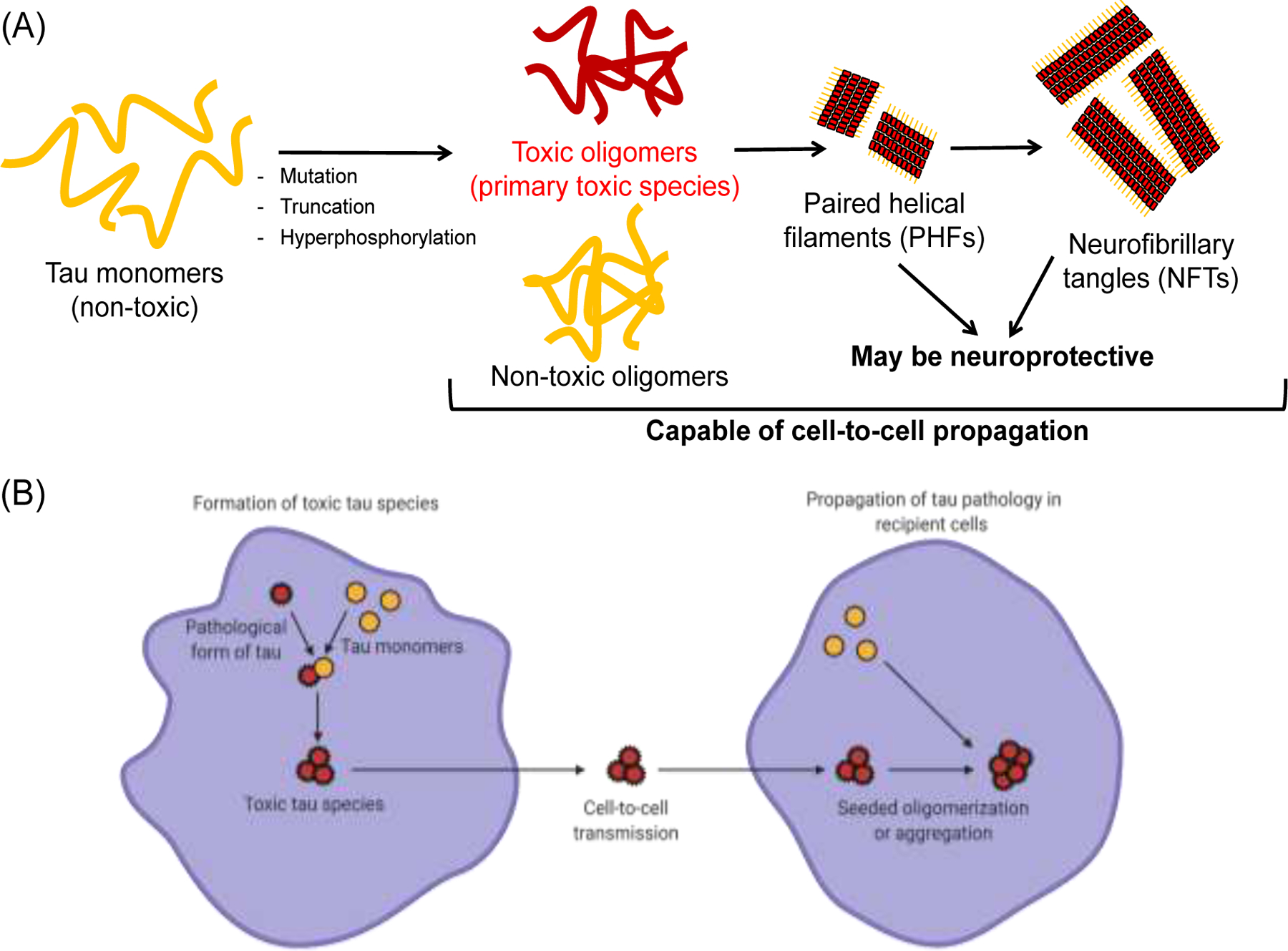

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the 6th leading cause of death in the United States, and there are more than 25 million people suffering from AD worldwide. While several hypotheses have been proposed to elucidate the disease mechanisms, the exact cause of AD pathology is still unknown and remains to be investigated. Wild-type (WT) MAPT gene encoding for microtubule-associated protein tau is carried by most patients with tauopathy, and aberrant accumulation of WT human tau is a hallmark of sporadic AD [1, 2]. Tau is an intrinsically disordered protein and a microtubule binding protein that plays an important role in the regulation of microtubule stability and axonal transport [3]. Under pathological conditions, tau is hyperphosphorylated and detached from microtubules, and it undergoes misfolding and conformational changes. Cytosolic accumulation of tau triggers the fibrillogenesis pathway, with monomers spontaneously forming into oligomers in the initial stage followed by subsequent fibrillization into intracellular paired helical filaments (PHFs) and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) (Fig. 1A) [4].

Fig. 1. Tau oligomerization/aggregation cascade and cell-to-cell propagation.

(A) The intrinsically disordered tau monomer is capable of forming tau oligomers spontaneously and producing both toxic and non-toxic soluble tau species. Subsequently, tau oligomers are able to form large insoluble aggregates with β-sheet structures, including paired helical filaments (PHFs) and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). PHFs and NFTs may be neuroprotective by sequestering toxic oligomers. (B) The toxic tau species (oligomers or aggregates) can be secreted by cells and transmitted to nearby recipient cells. In recipient cells, the uptake of toxic species can further induce seeded oligomerization or aggregation, resulting in cell-to-cell propagation of disease pathology. Schematics were created with BioRender.com.

While the presence of the large insoluble NFTs in the brain have been previously suggested to be the main cause of cognitive impairment, recent studies suggest that the spontaneously formed soluble tau oligomers prior to fibrillization contain the principal toxic tau species [5–12]. These toxic tau oligomers induce neuronal cell death as well as neurodegeneration and AD pathology in animal models including mice, Drosophila and Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans). While tau proteins may contain mutations or undergo other pathogenic processes such as truncation, and specific regions of tau (e.g. repeat domains) have been identified to be more aggregation-prone [13], the focus of this review will be on WT tau proteins which are less susceptible to fibrillization and mainly involved in the early oligomerization process. We will specifically discuss the critical roles of WT tau in AD pathogenesis, including tau-induced toxicity, formation of tau oligomers as well as their involvement in cell-to-cell propagation of disease pathology (Fig. 1B).

Tau toxicity

The gain of the toxic function of tau has been primarily attributed to the formation of toxic tau oligomers [10, 14]. The toxic tau oligomers have been postulated to cause cellular dysfunctions such as mitochondrial impairments and apoptosis induced by activated caspase, both of which impede synaptic energy production and result in cell death [15, 16]. These oligomers can be either on- or off-pathway, where on-pathway corresponds to their ability to subsequently form fibrils, and off-pathway does not fibrillize. In addition, the tau oligomers are capable of inducing tau misfolding and promoting propagation of tau pathology, thereby enhancing their toxicity. In this section, we will review the toxicity of WT tau, and we will summarize the formation of oligomers and discuss the mechanism of tau spreading in the subsequent sections.

In an initial study, the formation of filamentous inclusions is not observed with an overexpression of human WT tau in the mouse brain [17]. Strikingly, it has been further reported that these aged mice expressing WT human tau exhibit synaptic dysfunction [18] as well as learning and memory impairments [19], but in the absence of overt neuronal loss and without the formation of NFTs [20–22]. In addition, it has been shown that the presence of both 3R and 4R isoforms, instead of a single isoform, enhance tau pathology and neurodegeneration [23]. Importantly, in mouse models that show the formation of NFTs, neurodegeneration is not observed [5, 20, 24, 25]. Furthermore, reducing the endogenous expression of tau slows the disease progression [5, 26] and ameliorates memory impairments caused by β-amyloid (Aβ) [27]. These data suggest a crucial role of tau accumulation and toxic tau oligomer formation in neurodegeneration and memory loss [5].

Drosophila models of tauopathies have certainly provided evidences and supported that non-fibrillar tau oligomers are the primary toxic species. First, there is evidence that apoptosis (characterized by TUNEL-positive cells) occurs in models expressing WT human tau in neurons and glia, which gives rise to the well-characterized “rough-eye phenotype” as an indicator of neurodegeneration [28, 29]. More importantly, in nearly all Drosophila models of tauopathy, neurodegeneration occurs in the absence of insoluble tau aggregate formation, implying that dysfunction and toxicity may be caused by soluble tau oligomers and other cellular processes [6, 30–35]. These models provide insights into the mechanism by which tau causes dysfunction early in the disease process [6, 34] and have also been applied as a platform for drug screening [36]. Another widely used model of tauopathy is the nematode C. elegans expressing human tau. Although tau oligomerization and aggregation are not well characterized [37, 38], C. elegans expressing human WT tau result in neuronal dysfunction, defective locomotion [39–41], and tau spreading [42].

In terms of cellular assays, treatment of human cells with either synthetic tau oligomers (that are either β-sheet positive or negative) or fibrils made from exogenously purified tau proteins has led to multiple reports of cell cytotoxicity [8, 43–47]. These purified tau oligomers are made with a high concentration of the tau proteins or through the aid of exogenous aggregation inducers such as heparin or Aβ oligomers [48–54]. Despite the ability to induce toxicity, these systems do not recapitulate the cellular environment, lacking the numerous chaperone proteins that may be required to produce the ensemble of tau oligomers that populate the fibrillogenesis cascade [55, 56]. Hence, there is a need to shift to the cellular systems which contain these molecular constituents. However, there has been conflicting evidences of the toxicity of tau in the cellular overexpression systems. In some studies, overexpression of both mutant tau [57–62] and WT tau [63–66] results in cell death. Specifically, it has been reported that the overexpression of non-endogenous human WT tau in cultured murine neurons can cause synapse loss and mitochondria trafficking deficits [63], as well as disruption in mitochondrial dynamics and functions [64]. On the other hand, several other studies have reported that overexpression of WT tau does not cause cell cytotoxicity, despite tau hyperphosphorylation and formation of aggregates [55, 61, 62, 67–69]. It has been proposed that the inconsistencies across these cellular studies are due to the utilization of different cell lines. In addition, the different outcomes in cell cytotoxicity may also be due to co-expression of different isoforms or an imbalance in the normal tau isoform ratios (between 3R and 4R) [23, 70–72]. Furthermore, it has been suggested that the conformations of tau oligomers formed by WT tau may represent those that are observed in mutant tau and can inform the targeting of both toxic WT and mutant tau oligomers [61]. Regardless, abnormally modified tau intermediates or early-stage spontaneously formed tau oligomers have been suggested to be more neurotoxic than fibrillary species. However, it remains to be clarified which tau intermediates and which mechanisms are critical for neurodegeneration and AD pathology.

Formation of tau oligomers

Tau oligomers exist as an ensemble of distinct assemblies which include both toxic and non-toxic, on- and off-pathway species along the fibrillogenesis cascade [73–79]. It is therefore imperative to understand WT tau oligomerization from the biochemical and biophysical perspectives. WT tau has not been a focus in the field in the past decades mainly because of the initial perception that the fibrillar species of tau is the toxic species and that WT tau is shown to be incapable of spontaneously forming fibrils by themselves [80–83]. However, it has been widely shown that addition of aggregation inducers such as heparin to WT tau proteins will induce the formation of oligomers and fibrils both in purified proteins and in cells [82, 84]. Conventionally, treatment of purified tau proteins with aggregation inducers such as heparin, arachidonic acid, Congo Red, and tau fibrils as seeds results in the formation of insoluble and thioflavin-T (ThT) positive β-sheet fibrils, as characterized by circular dichroism and electron microscopy [85].

Recently, soluble and ThT positive β-sheet oligomers have been reported to be more toxic than fibrils. These soluble and ThT positive β-sheet oligomers can be generated by treatment of tau proteins with heparin (at different conditions to that of fibril formation), arachidonic acid, hexafluorisopropanol, and Aβ oligomers as seeds [86–97]. The main distinct feature of oligomers that differentiates them from fibrils is the lack of an obvious insoluble elongated fibrillar species, and soluble oligomers can typically be resolved by size exclusion chromatography to identify the number of monomers involved. In addition, these oligomers can also be made through highly concentrated tau proteins followed by centrifugation [98, 99]. On the other hand, other studies have illustrated tau toxicity related to soluble and ThT negative non-β-sheet oligomers [100–104]. These oligomers are typically formed spontaneously by disulfide bonds or through direct isolations from mouse brains, and they typically form dimers or trimers [101–104]. In contrast to the purified protein approach, tau oligomerization has also been studied in cells through engineering of tau cellular biosensors, primarily by fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) [105] and biomolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) [106]. FRET is a phenomenon observed when a pair of fluorophores with spectral overlap are in proximity due to the interaction of their fused proteins of interest, in this case, tau oligomerization or aggregation [61, 107, 108]. On the other hand, split fluorescent or luciferase proteins are fused to tau in the BiFC approach, and fluorescence or luciferase is observed when tau is oligomerized or self-associated [109–112]. Overexpression of WT tau in living cells results in FRET and BiFC signals, recapitulating tau oligomerization.

Several factors determine the degree of oligomerization (number of self-assembled monomers) of WT tau, including protein concentration, incubation time, as well as different tau isoforms. Although there is clearly a concentration-dependent effect in tau oligomerization [98, 112], several studies have proposed that dimeric and trimeric tau oligomers are the main toxic species under physiological conditions [46, 101–103]. There are other studies that propose a formation of hexamers [113–115] or decamers [116, 117], but no specific toxic tau oligomer species has been isolated or identified to date. The exact number of monomers to oligomerize and induce toxicity remains unclear [14, 118, 119]. In addition, when aggregation inducers are used, it is important to control the concentration of proteins and the amount of inducers used, so as to avoid generating fibrils or a mixture of oligomer/fibril populations that may result in challenges in purification and difficulty in data interpretations. Most studies have shown a range of incubation times, between 12 to 96 hours in cellular systems with overexpressed tau [61] and up to 144 hours in purified proteins [98]. The peak of tau oligomerization is generally between 24–48 hours in both systems (particularly with inducers in purified proteins). Some studies show that oligomerization decreases with time due to dissociation [110], while most studies show the transition of oligomers into fibrils with time. Interestingly, it has been postulated that the formation of fibrils reduces toxic tau oligomers by sequestering them [61, 120, 121]. Most studies focus on investigating homo-oligomers (oligomers made up of same isoforms) [61, 110]. However, several studies have tested the effect of oligomerization with hetero-oligomers made up of different isoforms, and they have suggested that hetero-oligomers have a higher tendency to oligomerize or aggregate [122, 123] and affect cellular functions differently [70, 124]. Further research still needs to be conducted to find out how different tau isoforms, post-translation modifications, and mutations alter the conformations of tau oligomers. Lastly, the specific tau species that determines the toxicity remains to be investigated.

Cell-to-cell spreading

WT tau aggregation and related functions may not accurately predict the molecular and cellular mechanisms. Furthermore, WT tau aggregation may not provide a total understanding of the mechanisms that drive tau pathology in AD. Therefore, we have to look into other specific events involved in the progression of the pathology, including cell-to-cell migration of tau [125–127] and age-dependent tau spreading [128], that induce toxicity and affect neuronal cell death [96]. The cell-to-cell spreading phenomenon has been investigated both in vitro, by the ability of cells to secrete and uptake tau, and in vivo. Tau secretion is typically monitored by the amount of tau released into the cell culture medium in the naked form [129, 130], as well as through other vesicles such as exosomes [131] and other membrane vesicles [132]. In both human and mice, there is a very low concentration of extracellular tau. For example, in healthy control cerebral spinal fluid (CSF), the concentration of tau is ~0.16 ng/mL , while the concentration is ~0.85 ng/mL in AD patients [133]. Likewise, the concentration of tau in wild-type mouse interstitial fluid (ISF) is ~30–40 ng/mL [134]. This small amount of tau secretion is typically measured and quantified by highly sensitive affinity assays such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA). On the other hand, cellular uptake of tau is analyzed by fluorescent assays using purified tau proteins stained with fluorescent probes or dyes that can be tracked via fluorescence microscopy.

In terms of cell-to-cell propagation of tau, it has been demonstrated that isolated WT human tau oligomers or filaments/seeds from AD brain can induce tau aggregation in human neurons without tau overexpression or pathological mutations, and also in other neuronal cells overexpressing WT tau [135–139]. As a result of tau spreading, observations consistent with AD tau pathology have been reported, including an increase in phosphorylated tau, changes in tau conformation [140], and induction of neuronal cell death [96]. Although all forms of tau have the ability to spread and induce further aggregation, some studies have shown that tau fibrils [140] and tau monomers [141] have reduced spreading capability. To monitor the cellular release, uptake, and propagation of tau at physiological concentrations and in real-time, previously discussed FRET and BiFC assays have been employed. For example, it has been shown that the unlabeled repeat domain (RD) aggregates are released from one cell population (expressing RD aggregates) to recipient tau FRET biosensor cells, and inducing aggregation (as illustrated through an increase in FRET). This indicates the propagation of seeds and the seeded aggregation between cells [108, 142–144]. In BiFC assays, split-luciferase tagged tau proteins illustrate increased luciferase signals with increasing tau concentrations of 0.01–1000 ng/mL, supporting that tau oligomers can be actively released and taken up by cells and neurons in vitro [110]. In animal studies, recent data illustrate that the injection or intracellular inoculation of synthetic or brain-derived tau oligomers and aggregates (or brain extracts) into WT mice may induce tau pathology and propagation [136, 138, 145, 146]. Additionally, transfer of tau aggregates can take place between cells in vivo [138, 147–151]. Functionally, propagation of tau oligomers and aggregates in mice results in inhibition of long-term potentiation (LTP), memory impairments [15, 152, 153], mitochondria dysfunction, and neuronal death.

The requirement of tau and its key role in cell-to-cell spreading have been illustrated by studies showing that no inclusions are formed and no pathology is observed when the recipient mice do not contain tau or when tau is depleted from the extracts prior to injection [150]. In terms of the propagation mechanism, studies have shown that there is a trans-synaptic transfer of WT human tau proteins even at distant brain regions [154]. In addition, WT tau spreads further than mutated tau which resides near the immunosynapse [154, 155], although it is suggested that transmission of tauopathy strains is independent of their isoform composition [156]. It is also crucial to note that isolated tau tangles from patients possess the strongest seeding ability, followed by aggregated tau extracted from transgenic mouse brain, which induces inclusion formation at a higher efficiency than aggregated recombinant human tau [138, 157–159]. Most importantly, it remains to be answered which tau species plays the major role in cell-to-cell propagation and what concentrations are required to initiate the spreading.

Conclusion

Tau proteins play key roles in physiological functions, but they are also involved in AD and tauopathy disease mechanisms. Recently, WT tau has received increasing attention, as spontaneously formed tau oligomers made up of tau proteins with less fibrillization tendency (e.g. WT tau), rather than large fibrillar aggregates, have been proposed to be the primary toxic species. This suggests the need to target WT tau for therapeutic discovery and biomarker development. In addition, each of the tauopathy models, both in vitro and in vivo, have their own advantages and limitations that should be taken into account when choosing the appropriate models for studies [160]. Many questions remain about the role of WT tau in toxicity, formation of oligomers, and cell-to-cell propagation. These questions include (1) What comprises the toxic tau species, and do they involve a specific population of tau monomers, dimers, or oligomers (or a combination of them); (2) Are the neurotoxicity effects of soluble tau species due to an abnormal tau accumulation, or do they play actual functions; and (3) Do these soluble tau species represent signs of early stage of AD pathogenesis.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants to J.N.S. (RF1AG053951 and R43AG063675). C.H.L. was supported by a Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship from the University of Minnesota. C.H.L. is currently a Young NUS Fellow and a recipient of the NUS Development Grant from the National University of Singapore.

References

- 1.Grundke-Iqbal I, et al. , Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1986. 83(13): p. 4913–4917. 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chi H, Sang T-K, and Chang H-Y, Tauopathy. IntechOpen, 2018. 10.5772/intechopen.73198 [DOI]

- 3.AVILA J, et al. , Role of Tau Protein in Both Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Physiological Reviews, 2004. 84(2): p. 361–384. 10.1152/physrev.00024.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballatore C, Lee VMY, and Trojanowski JQ, Tau-mediated neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2007. 8(9): p. 663–672. 10.1038/nrn2194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santacruz K, et al. , Tau suppression in a neurodegenerative mouse model improves memory function. Science (New York, N.Y.), 2005. 309(5733): p. 476–481. 10.1126/science.1113694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wittmann CW, et al. , Tauopathy in Drosophila: Neurodegeneration Without Neurofibrillary Tangles. Science, 2001. 293(5530): p. 711–714. 10.1126/science.1062382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dujardin S, et al. , Tau molecular diversity contributes to clinical heterogeneity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Medicine, 2020. 26(8): p. 1256–1263. 10.1038/s41591-020-0938-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maeda S, et al. , Increased levels of granular tau oligomers: An early sign of brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience Research, 2006. 54(3): p. 197–201. 10.1016/j.neures.2005.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berger Z, et al. , Accumulation of pathological tau species and memory loss in a conditional model of tauopathy. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 2007. 27(14): p. 3650–3662. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0587-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerson JE, Castillo-Carranza DL, and Kayed R, Advances in Therapeutics for Neurodegenerative Tauopathies: Moving toward the Specific Targeting of the Most Toxic Tau Species. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 2014. 5(9): p. 752–769. 10.1021/cn500143n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guzmán-Martinez L, Farías GA, and Maccioni RB, Tau oligomers as potential targets for Alzheimer’s diagnosis and novel drugs. Frontiers in neurology, 2013. 4: p. 167–167. 10.3389/fneur.2013.00167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lo Cascio F, et al. , Modulating Disease-Relevant Tau Oligomeric Strains by Small Molecules. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2020. 10.1074/jbc.RA120.014630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Iqbal K, et al. , Tau pathology in Alzheimer disease and other tauopathies. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease, 2005. 1739(2): p. 198–210. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kopeikina KJ, Hyman BT, and Spires-Jones TL, Soluble forms of tau are toxic in Alzheimer’s disease. Translational neuroscience, 2012. 3(3): p. 223–233. 10.2478/s13380-012-0032-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lasagna-Reeves CA, et al. , Tau oligomers impair memory and induce synaptic and mitochondrial dysfunction in wild-type mice. Molecular neurodegeneration, 2011. 6: p. 39–39. 10.1186/1750-1326-6-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shafiei SS, Guerrero-Muñoz MJ, and Castillo-Carranza DL, Tau Oligomers: Cytotoxicity, Propagation, and Mitochondrial Damage. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 2017. 9: p. 83–83. 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Götz J, et al. , Somatodendritic localization and hyperphosphorylation of tau protein in transgenic mice expressing the longest human brain tau isoform. The EMBO journal, 1995. 14(7): p. 1304–1313. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07116.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoover BR, et al. , Tau mislocalization to dendritic spines mediates synaptic dysfunction independently of neurodegeneration. Neuron, 2010. 68(6): p. 1067–1081. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimura T, et al. , Hyperphosphorylated tau in parahippocampal cortex impairs place learning in aged mice expressing wild-type human tau. The EMBO journal, 2007. 26(24): p. 5143–5152. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andorfer C, et al. , Cell-cycle reentry and cell death in transgenic mice expressing nonmutant human tau isoforms. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 2005. 25(22): p. 5446–5454. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4637-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andorfer C, et al. , Hyperphosphorylation and aggregation of tau in mice expressing normal human tau isoforms. Journal of Neurochemistry, 2003. 86(3): p. 582–590. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.200301879.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeugd A.V.d., et al. , Hippocampal tauopathy in tau transgenic mice coincides with impaired hippocampus-dependent learning and memory, and attenuated late-phase long-term depression of synaptic transmission. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 2011. 95(3): p. 296–304. 10.1016/j.nlm.2010.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cox K, et al. , Analysis of isoform-specific tau aggregates suggests a common toxic mechanism involving similar pathological conformations and axonal transport inhibition. Neurobiology of aging, 2016. 47: p. 113–126. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.07.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spires TL, et al. , Region-specific dissociation of neuronal loss and neurofibrillary pathology in a mouse model of tauopathy. The American journal of pathology, 2006. 168(5): p. 1598–1607. 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morsch R, Simon W, and Coleman PD, Neurons May Live for Decades with Neurofibrillary Tangles. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology, 1999. 58(2): p. 188–197. 10.1097/00005072-199902000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boutajangout A, Quartermain D, and Sigurdsson EM, Immunotherapy targeting pathological tau prevents cognitive decline in a new tangle mouse model. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 2010. 30(49): p. 16559–16566. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4363-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vossel KA, et al. , Tau reduction prevents Abeta-induced defects in axonal transport. Science (New York, N.Y.), 2010. 330(6001): p. 198–198. 10.1126/science.1194653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shulman JM and Feany MB, Genetic modifiers of tauopathy in Drosophila. Genetics, 2003. 165(3): p. 1233–1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blard O, et al. , Cytoskeleton proteins are modulators of mutant tau-induced neurodegeneration in Drosophila. Human Molecular Genetics, 2007. 16(5): p. 555–566. 10.1093/hmg/ddm011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feuillette S, et al. , Drosophila models of human tauopathies indicate that Tau protein toxicity in vivo is mediated by soluble cytosolic phosphorylated forms of the protein. Journal of Neurochemistry, 2010. 113(4): p. 895–903. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06663.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cowan CM, et al. , Modelling tauopathies in Drosophila: insights from the fruit fly. International journal of Alzheimer’s disease, 2011. 2011: p. 598157–598157. 10.4061/2011/598157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prüßing K, Voigt A, and Schulz JB, Drosophila melanogaster as a model organism for Alzheimer’s disease. Molecular Neurodegeneration, 2013. 8(1): p. 35. 10.1186/1750-1326-8-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tue NT, et al. Insights from Drosophila melanogaster model of Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in bioscience (Landmark edition), 2020. 25, 134–146 DOI: 10.2741/4798 . 10.2741/4798https://doi.org/10.2741/4798. https://doi.org/10.2741/4798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams DW, Tyrer M, and Shepherd D, Tau and tau reporters disrupt central projections of sensory neurons in Drosophila. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 2000. 428(4): p. 630–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feuillette S, et al. , A Connected Network of Interacting Proteins Is Involved in Human-Tau Toxicity in Drosophila. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 2020. 14(68). 10.3389/fnins.2020.00068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shim K-H, et al. , Small-molecule drug screening identifies drug Ro 31–8220 that reduces toxic phosphorylated tau in Drosophila melanogaster. Neurobiology of Disease, 2019. 130: p. 104519. 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.104519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guha S, et al. , Alzheimer’s disease-relevant tau modifications selectively impact neurodegeneration and mitophagy in a novel C. elegans single-copy transgenic model. bioRxiv, 2020: p. 2020.02.12.946004. 10.1101/2020.02.12.946004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Miyasaka T, et al. , Curcumin improves tau-induced neuronal dysfunction of nematodes. Neurobiology of Aging, 2016. 39: p. 69–81. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyasaka T, et al. , Imbalanced Expression of Tau and Tubulin Induces Neuronal Dysfunction in C. elegans Models of Tauopathy. Frontiers in neuroscience, 2018. 12: p. 415–415. 10.3389/fnins.2018.00415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pir GJ, et al. , Suppressing Tau Aggregation and Toxicity by an Anti-Aggregant Tau Fragment. Molecular Neurobiology, 2019. 56(5): p. 3751–3767. 10.1007/s12035-018-1326-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brandt R, et al. , A Caenorhabditis elegans model of tau hyperphosphorylation: Induction of developmental defects by transgenic overexpression of Alzheimer’s disease-like modified tau. Neurobiology of Aging, 2009. 30(1): p. 22–33. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sandhof CA, et al. , C. elegans Models to Study the Propagation of Prions and Prion-Like Proteins. Biomolecules, 2020. 10(8): p. 1188. 10.3390/biom10081188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lasagna-Reeves CA, et al. , Identification of oligomers at early stages of tau aggregation in Alzheimer’s disease. The FASEB Journal, 2012. 26(5): p. 1946–1959. 10.1096/fj.11-199851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Flach K, et al. , Tau oligomers impair artificial membrane integrity and cellular viability. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2012. 10.1074/jbc.M112.396176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Ward SM, et al. , Tau oligomers and tau toxicity in neurodegenerative disease. Biochemical Society transactions, 2012. 40(4): p. 667–671. 10.1042/BST20120134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tian H, et al. , Trimeric Tau Is Toxic to Human Neuronal Cells at Low Nanomolar Concentrations. International Journal of Cell Biology, 2013. 2013: p. 260787. 10.1155/2013/260787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rane JS, Kumari A, and Panda D, An acetylation mimicking mutation, K274Q, in tau imparts neurotoxicity by enhancing tau aggregation and inhibiting tubulin polymerization. Biochemical Journal, 2019. 476(10): p. 1401–1417. 10.1042/BCJ20190042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lo Cascio F and Kayed R, Azure C Targets and Modulates Toxic Tau Oligomers. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 2018. 9(6): p. 1317–1326. 10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wischik CM, et al. , Selective inhibition of Alzheimer disease-like tau aggregation by phenothiazines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1996. 93(20): p. 11213–11218. 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wobst HJ, et al. , The green tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin gallate prevents the aggregation of tau protein into toxic oligomers at substoichiometric ratios. FEBS Letters, 2015. 589(1): p. 77–83. 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.11.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rane JS, Bhaumik P, and Panda D, Curcumin Inhibits Tau Aggregation and Disintegrates Preformed Tau Filaments in vitro. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 2017. 60(3): p. 999–1014. 10.3233/JAD-170351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang P, et al. , Binding and neurotoxicity mitigation of toxic tau oligomers by synthetic heparin like oligosaccharides. Chemical Communications, 2018. 54(72): p. 10120–10123. 10.1039/C8CC05072D [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taniguchi S, et al. , Inhibition of Heparin-induced Tau Filament Formation by Phenothiazines, Polyphenols, and Porphyrins. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2005. 280(9): p. 7614–7623. 10.1074/jbc.M408714200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baggett DW and Nath A, The Rational Discovery of a Tau Aggregation Inhibitor. Biochemistry, 2018. 57(42): p. 6099–6107. 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bandyopadhyay B, et al. , Tau Aggregation and Toxicity in a Cell Culture Model of Tauopathy. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2007. 282(22): p. 16454–16464. 10.1074/jbc.M700192200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blair LJ, et al. , Accelerated neurodegeneration through chaperone-mediated oligomerization of tau. The Journal of clinical investigation, 2013. 123(10): p. 4158–4169. 10.1172/JCI69003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhao Z, et al. , A role of P301L tau mutant in anti-apoptotic gene expression, cell cycle and apoptosis. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience, 2003. 24(2): p. 367–379. 10.1016/S1044-7431(03)00175-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khlistunova I, et al. , Inducible Expression of Tau Repeat Domain in Cell Models of Tauopathy: AGGREGATION IS TOXIC TO CELLS BUT CAN BE REVERSED BY INHIBITOR DRUGS. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2006. 281(2): p. 1205–1214. 10.1074/jbc.M507753200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tackenberg C and Brandt R, Divergent Pathways Mediate Spine Alterations and Cell Death Induced by Amyloid-β, Wild-Type Tau, and R406W Tau. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2009. 29(46): p. 14439–14450. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3590-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van Swieten J and Spillantini MG, Hereditary Frontotemporal Dementia Caused by Tau Gene Mutations. Brain Pathology, 2007. 17(1): p. 63–73. 10.1111/j.1750-3639.200700052.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lo CH, et al. , Targeting the ensemble of heterogeneous tau oligomers in cells: A novel small molecule screening platform for tauopathies. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 2019. 15(11): p. 1489–1502. 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.06.4954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pickhardt M, et al. , Time course of Tau toxicity and pharmacologic prevention in a cell model of Tauopathy. Neurobiology of Aging, 2017. 57: p. 47–63. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thies E and Mandelkow E-M, Missorting of tau in neurons causes degeneration of synapses that can be rescued by the kinase MARK2/Par-1. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 2007. 27(11): p. 2896–2907. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4674-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li X-C, et al. , Human wild-type full-length tau accumulation disrupts mitochondrial dynamics and the functions via increasing mitofusins. Scientific reports, 2016. 6: p. 24756–24756. 10.1038/srep24756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ozcelik S, et al. , Co-expression of truncated and full-length tau induces severe neurotoxicity. Molecular Psychiatry, 2016. 21(12): p. 1790–1798. 10.1038/mp.2015.228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hall GF, Yao J, and Lee G, Human tau becomes phosphorylated and forms filamentous deposits when overexpressed in lamprey central neurons in situ. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 1997. 94(9): p. 4733–4738. 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hu J-Y, et al. , Pathological concentration of zinc dramatically accelerates abnormal aggregation of full-length human Tau and thereby significantly increases Tau toxicity in neuronal cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease, 2017. 1863(2): p. 414–427. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tepper K, et al. , Oligomer formation of tau protein hyperphosphorylated in cells. The Journal of biological chemistry, 2014. 289(49): p. 34389–34407. 10.1074/jbc.M114.611368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fath T, Eidenmüller J, and Brandt R, Tau-mediated cytotoxicity in a pseudohyperphosphorylation model of Alzheimer’s disease. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 2002. 22(22): p. 9733–9741. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-22-09733.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sealey MA, et al. , Distinct phenotypes of three-repeat and four-repeat human tau in a transgenic model of tauopathy. Neurobiology of Disease, 2017. 105: p. 74–83. 10.1016/j.nbd.2017.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schoch KM, et al. , Increased 4R-Tau Induces Pathological Changes in a Human-Tau Mouse Model. Neuron, 2016. 90(5): p. 941–947. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.04.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wu L, et al. , Human Tau Isoform Aggregation and Selective Detection of Misfolded Tau from Post-Mortem Alzheimer’s Disease Brains. bioRxiv, 2020: p. 2019.12.31.876946. 10.1101/2019.12.31.876946 [DOI]

- 73.Nath A, et al. , The conformational ensembles of α-synuclein and tau: combining single-molecule FRET and simulations. Biophysical journal, 2012. 103(9): p. 1940–1949. 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.09.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Akoury E, et al. , Inhibition of Tau Filament Formation by Conformational Modulation. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2013. 135(7): p. 2853–2862. 10.1021/ja312471h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gerson JE, Mudher A, and Kayed R, Potential mechanisms and implications for the formation of tau oligomeric strains. Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 2016. 51(6): p. 482–496. 10.1080/10409238.2016.1226251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weaver CL, et al. , Conformational change as one of the earliest alterations of tau in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging, 2000. 21(5): p. 719–727. 10.1016/S0197-4580(00)00157-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sharma AM, et al. , Tau monomer encodes strains. eLife, 2018. 7: p. e37813. 10.7554/eLife.37813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mirbaha H, et al. , Inert and seed-competent tau monomers suggest structural origins of aggregation. eLife, 2018. 7: p. e36584. 10.7554/eLife.36584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Huang RY-C, et al. , Probing Conformational Dynamics of Tau Protein by Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry. Journal of The American Society for Mass Spectrometry, 2018. 29(1): p. 174–182. 10.1007/s13361-017-1815-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kuret J, et al. , Evaluating triggers and enhancers of tau fibrillization. Microscopy Research and Technique, 2005. 67(3‐4): p. 141–155. 10.1002/jemt.20187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ko L.-w., et al. , Cellular Models for Tau Filament Assembly. Vol. 19. 2003. 311–6. 10.1385/JMN:19:3:309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chirita CN, et al. , Triggers of Full-Length Tau Aggregation: A Role for Partially Folded Intermediates. Biochemistry, 2005. 44(15): p. 5862–5872. 10.1021/bi0500123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ferrari A, et al. , β-Amyloid Induces Paired Helical Filament-like Tau Filaments in Tissue Culture. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2003. 278(41): p. 40162–40168. 10.1074/jbc.M308243200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mamun A, et al. , Toxic tau: structural origins of tau aggregation in Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Regeneration Research, 2020. 15(8): p. 1417–1420. 10.4103/1673-5374.274329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nizynski B, Dzwolak W, and Nieznanski K, Amyloidogenesis of Tau protein. Protein Science, 2017. 26(11): p. 2126–2150. 10.1002/pro.3275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xu J, et al. , Tau-tubulin kinase 1 enhances prefibrillar tau aggregation and motor neuron degeneration in P301L FTDP-17 tau-mutant mice. Faseb j, 2010. 24(8): p. 2904–15. 10.1096/fj.09-150144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Flach K, et al. , Tau Oligomers Impair Artificial Membrane Integrity and Cellular Viability. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2012. 287(52): p. 43223–43233. 10.1074/jbc.M112.396176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Barghorn S, Biernat J, and Mandelkow E, Purification of Recombinant Tau Protein and Preparation of Alzheimer-Paired Helical Filaments In Vitro, in Amyloid Proteins: Methods and Protocols, Sigurdsson EM, Editor. 2005, Humana Press: Totowa, NJ. p. 35–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sonawane SK, et al. , Baicalein suppresses Repeat Tau fibrillization by sequestering oligomers. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 2019. 675: p. 108119. 10.1016/j.abb.2019.108119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Majerova P, et al. , Microglia display modest phagocytic capacity for extracellular tau oligomers. Journal of Neuroinflammation, 2014. 11(1): p. 161. 10.1186/s12974-014-0161-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ono K and Yamada M, Low-n oligomers as therapeutic targets of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neurochemistry, 2011. 117(1): p. 19–28. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.201107187.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kaniyappan S, et al. , Extracellular low-n oligomers of tau cause selective synaptotoxicity without affecting cell viability. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 2017. 13(11): p. 1270–1291. 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Das R, Balmik AA, and Chinnathambi S, Phagocytosis of full-length Tau oligomers by Actin-remodeling of activated microglia. Journal of Neuroinflammation, 2020. 17(1): p. 10. 10.1186/s12974-019-1694-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lasagna-Reeves CA, et al. , Preparation and Characterization of Neurotoxic Tau Oligomers. Biochemistry, 2010. 49(47): p. 10039–10041. 10.1021/bi1016233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gerson JE, Sengupta U, and Kayed R, Tau Oligomers as Pathogenic Seeds: Preparation and Propagation In Vitro and In Vivo. Methods Mol Biol, 2017. 1523: p. 141–157. 10.1007/978-1-4939-6598-4_9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gómez-Ramos A, et al. , Extracellular tau is toxic to neuronal cells. FEBS Letters, 2006. 580(20): p. 4842–4850. 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.07.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Patterson KR, et al. , Characterization of prefibrillar Tau oligomers in vitro and in Alzheimer disease. The Journal of biological chemistry, 2011. 286(26): p. 23063–23076. 10.1074/jbc.M111.237974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Maeda S, et al. , Granular Tau Oligomers as Intermediates of Tau Filaments. Biochemistry, 2007. 46(12): p. 3856–3861. 10.1021/bi061359o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Maeda S and Takashima A, Oligomers Tau, in Tau Biology, Takashima A, Wolozin B, and Buee L, Editors. 2019, Springer Singapore: Singapore. p. 373–380. 10.1007/978-981-32-9358-8_27 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Usenovic M, et al. , Internalized Tau Oligomers Cause Neurodegeneration by Inducing Accumulation of Pathogenic Tau in Human Neurons Derived from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2015. 35(42): p. 14234–14250. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1523-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sahara N, et al. , Assembly of two distinct dimers and higher-order oligomers from full-length tau. European Journal of Neuroscience, 2007. 25(10): p. 3020–3029. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.200705555.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Soeda Y, et al. , Toxic tau oligomer formation blocked by capping of cysteine residues with 1,2-dihydroxybenzene groups. Nature Communications, 2015. 6(1): p. 10216. 10.1038/ncomms10216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Haque MM, et al. , Inhibition of tau aggregation by a rosamine derivative that blocks tau intermolecular disulfide cross-linking. Amyloid, 2014. 21(3): p. 185–190. 10.3109/13506129.2014.929103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Manassero G, et al. , Dual Mechanism of Toxicity for Extracellular Injection of Tau Oligomers versus Monomers in Human Tau Mice. J Alzheimers Dis, 2017. 59(2): p. 743–751. 10.3233/JAD-170298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Algar WR, et al. , FRET as a biomolecular research tool - understanding its potential while avoiding pitfalls. Nature Methods, 2019. 16(9): p. 815–829. 10.1038/s41592-019-0530-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kudla J and Bock R, Lighting the Way to Protein-Protein Interactions: Recommendations on Best Practices for Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation Analyses. The Plant Cell, 2016. 28(5): p. 1002–1008. 10.1105/tpc.16.00043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chun W and Johnson GV, Activation of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta promotes the intermolecular association of tau. The use of fluorescence resonance energy transfer microscopy. J Biol Chem, 2007. 282(32): p. 23410–7. 10.1074/jbc.M703706200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kfoury N, et al. , Trans-cellular propagation of Tau aggregation by fibrillar species. The Journal of biological chemistry, 2012. 287(23): p. 19440–19451. 10.1074/jbc.M112.346072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Tak H, et al. , Bimolecular fluorescence complementation; lighting-up tau-tau interaction in living cells. PLoS One, 2013. 8(12): p. e81682. 10.1371/journal.pone.0081682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wegmann S, et al. , Formation, release, and internalization of stable tau oligomers in cells. Journal of neurochemistry, 2016. 139(6): p. 1163–1174. 10.1111/jnc.13866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Shin S, et al. , Visualization of soluble tau oligomers in TauP301L-BiFC transgenic mice demonstrates the progression of tauopathy. Progress in Neurobiology, 2020. 187: p. 101782. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2020.101782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chun W, Waldo GS, and Johnson GVW, Split GFP complementation assay: a novel approach to quantitatively measure aggregation of tau in situ: effects of GSK3β activation and caspase 3 cleavage. Journal of Neurochemistry, 2007. 103(6): p. 2529–2539. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04941.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kurnellas MP, et al. , Amyloid fibrils composed of hexameric peptides attenuate neuroinflammation. Science translational medicine, 2013. 5(179): p. 179ra42–179ra42. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chen X, et al. , Exploring the interplay between fibrillization and amorphous aggregation channels on the energy landscapes of tau repeat isoforms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2020. 117(8): p. 4125–4130. 10.1073/pnas.1921702117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Dangi A, et al. , Residue-based propensity of aggregation in the Tau amyloidogenic hexapeptides AcPHF6* and AcPHF6. RSC Advances, 2020. 10(46): p. 27331–27335. 10.1039/D0RA03809A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lasagna-Reeves CA, et al. , The formation of tau pore-like structures is prevalent and cell specific: possible implications for the disease phenotypes. Acta Neuropathologica Communications, 2014. 2(1): p. 56. 10.1186/2051-5960-2-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Fitzpatrick AWP, et al. , Cryo-EM structures of tau filaments from Alzheimer’s disease. Nature, 2017. 547(7662): p. 185–190. 10.1038/nature23002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Götz J, et al. , What Renders TAU Toxic. Frontiers in neurology, 2013. 4: p. 72–72. 10.3389/fneur.2013.00072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gendron TF and Petrucelli L, The role of tau in neurodegeneration. Molecular Neurodegeneration, 2009. 4(1): p. 13. 10.1186/1750-1326-4-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.d’Orange M, et al. , Potentiating tangle formation reduces acute toxicity of soluble tau species in the rat. Brain, 2017. 141(2): p. 535–549. 10.1093/brain/awx342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Yang J, et al. , Amelioration of aggregate cytotoxicity by catalytic conversion of protein oligomers into amyloid fibrils. Nanoscale, 2020. 12(36): p. 18663–18672. 10.1039/D0NR01481H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Do TD, et al. , Interactions between Amyloid-β and Tau Fragments Promote Aberrant Aggregates: Implications for Amyloid Toxicity. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 2014. 118(38): p. 11220–11230. 10.1021/jp506258g [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Iqbal K, Gong C-X, and Liu F, Hyperphosphorylation-induced tau oligomers. Frontiers in neurology, 2013. 4: p. 112–112. 10.3389/fneur.2013.00112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Liu C, et al. , Co-immunoprecipitation with Tau Isoform-specific Antibodies Reveals Distinct Protein Interactions and Highlights a Putative Role for 2N Tau in Disease. The Journal of biological chemistry, 2016. 291(15): p. 8173–8188. 10.1074/jbc.M115.641902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Brunello CA, et al. , Mechanisms of secretion and spreading of pathological tau protein. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 2020. 77(9): p. 1721–1744. 10.1007/s00018-019-03349-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Pérez M, et al. , Secretion of full-length tau or tau fragments in a cell culture model. Neuroscience letters, 2016. 634: p. 63–69. 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Merezhko M, Uronen R-L, and Huttunen HJ, The Cell Biology of Tau Secretion. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 2020. 13(180). 10.3389/fnmol.2020.569818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Wegmann S, et al. , Experimental evidence for the age dependence of tau protein spread in the brain. Science Advances, 2019. 5(6): p. eaaw6404. 10.1126/sciadv.aaw6404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Chai X, Dage JL, and Citron M, Constitutive secretion of tau protein by an unconventional mechanism. Neurobiology of Disease, 2012. 48(3): p. 356–366. 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Katsinelos T, et al. , Unconventional Secretion Mediates the Trans-cellular Spreading of Tau. Cell Reports, 2018. 23(7): p. 2039–2055. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.04.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wang Y, et al. , The release and trans-synaptic transmission of Tau via exosomes. Molecular Neurodegeneration, 2017. 12(1): p. 5. 10.1186/s13024-016-0143-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Simón D, et al. , Proteostasis of tau. Tau overexpression results in its secretion via membrane vesicles. FEBS Letters, 2012. 586(1): p. 47–54. 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Johnson GVW, et al. , The Tau Protein in Human Cerebrospinal Fluid in Alzheimer’s Disease Consists of Proteolytically Derived Fragments. Journal of Neurochemistry, 1997. 68(1): p. 430–433. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.199768010430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Yamada K, et al. , In Vivo Microdialysis Reveals Age-Dependent Decrease of Brain Interstitial Fluid Tau Levels in P301S Human Tau Transgenic Mice. The Journal of Neuroscience, 2011. 31(37): p. 13110–13117. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2569-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Audouard E, et al. , High-Molecular-Weight Paired Helical Filaments from Alzheimer Brain Induces Seeding of Wild-Type Mouse Tau into an Argyrophilic 4R Tau Pathology in Vivo. The American Journal of Pathology, 2016. 186(10): p. 2709–2722. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Guo JL, et al. , Unique pathological tau conformers from Alzheimer’s brains transmit tau pathology in nontransgenic mice. The Journal of experimental medicine, 2016. 213(12): p. 2635–2654. 10.1084/jem.20160833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.McEwan WA, et al. , Cytosolic Fc receptor TRIM21 inhibits seeded tau aggregation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2017. 114(3): p. 574–579. 10.1073/pnas.1607215114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Iba M, et al. , Synthetic tau fibrils mediate transmission of neurofibrillary tangles in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s-like tauopathy. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 2013. 33(3): p. 1024–1037. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2642-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Frost B, Jacks RL, and Diamond MI, Propagation of tau misfolding from the outside to the inside of a cell. The Journal of biological chemistry, 2009. 284(19): p. 12845–12852. 10.1074/jbc.M808759200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Usenovic M, et al. , Internalized Tau Oligomers Cause Neurodegeneration by Inducing Accumulation of Pathogenic Tau in Human Neurons Derived from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 2015. 35(42): p. 14234–14250. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1523-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Wu JW, et al. , Small misfolded Tau species are internalized via bulk endocytosis and anterogradely and retrogradely transported in neurons. The Journal of biological chemistry, 2013. 288(3): p. 1856–1870. 10.1074/jbc.M112.394528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Polanco JC, et al. , Extracellular Vesicles Isolated from the Brains of rTg4510 Mice Seed Tau Protein Aggregation in a Threshold-dependent Manner. The Journal of biological chemistry, 2016. 291(24): p. 12445–12466. 10.1074/jbc.M115.709485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Holmes BB, et al. , Proteopathic tau seeding predicts tauopathy in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2014. 111(41): p. E4376–E4385. 10.1073/pnas.1411649111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Furman JL, Holmes BB, and Diamond MI, Sensitive Detection of Proteopathic Seeding Activity with FRET Flow Cytometry. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE, 2015(106): p. e53205–e53205. 10.3791/53205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Stancu I-C, et al. , Templated misfolding of Tau by prion-like seeding along neuronal connections impairs neuronal network function and associated behavioral outcomes in Tau transgenic mice. Acta neuropathologica, 2015. 129(6): p. 875–894. 10.1007/s00401-015-1413-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Iba M, et al. , Tau pathology spread in PS19 tau transgenic mice following locus coeruleus (LC) injections of synthetic tau fibrils is determined by the LC’s afferent and efferent connections. Acta neuropathologica, 2015. 130(3): p. 349–362. 10.1007/s00401-015-1458-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.de Calignon A, et al. , Propagation of tau pathology in a model of early Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron, 2012. 73(4): p. 685–697. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.11.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Liu L, et al. , Trans-synaptic spread of tau pathology in vivo. PloS one, 2012. 7(2): p. e31302–e31302. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Clavaguera F, et al. , Brain homogenates from human tauopathies induce tau inclusions in mouse brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2013. 110(23): p. 9535–9540. 10.1073/pnas.1301175110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Clavaguera F, et al. , Transmission and spreading of tauopathy in transgenic mouse brain. Nature cell biology, 2009. 11(7): p. 909–913. 10.1038/ncb1901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Lasagna-Reeves CA, et al. , Identification of oligomers at early stages of tau aggregation in Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 2012. 26(5): p. 1946–1959. 10.1096/fj.11-199851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Lasagna-Reeves CA, et al. , Alzheimer brain-derived tau oligomers propagate pathology from endogenous tau. Scientific reports, 2012. 2: p. 700–700. 10.1038/srep00700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Cárdenas-Aguayo M.d.C., et al. , The Role of Tau Oligomers in the Onset of Alzheimer’s Disease Neuropathology. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 2014. 5(12): p. 1178–1191. 10.1021/cn500148z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Dujardin S, et al. , Neuron-to-neuron wild-type Tau protein transfer through a trans-synaptic mechanism: relevance to sporadic tauopathies. Acta Neuropathologica Communications, 2014. 2(1): p. 14. 10.1186/2051-5960-2-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Dujardin S, et al. , Different tau species lead to heterogeneous tau pathology propagation and misfolding. Acta Neuropathologica Communications, 2018. 6(1): p. 132. 10.1186/s40478-018-0637-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.He Z, et al. , Transmission of tauopathy strains is independent of their isoform composition. Nature Communications, 2020. 11(1): p. 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Clavaguera F, et al. , “Prion-Like” Templated Misfolding in Tauopathies. Brain Pathology, 2013. 23(3): p. 342–349. 10.1111/bpa.12044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Guo JL, et al. , Unique pathological tau conformers from Alzheimer’s brains transmit tau pathology in nontransgenic mice. Journal of Experimental Medicine, 2016. 213(12): p. 2635–2654. 10.1084/jem.20160833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Nam W-H and Choi YP, In vitro generation of tau aggregates conformationally distinct from parent tau seeds of Alzheimer’s brain. Prion, 2019. 13(1): p. 1–12. 10.1080/19336896.2018.1545524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Koechling T, et al. , Neuronal models for studying tau pathology. International journal of Alzheimer’s disease, 2010. 2010: p. 528474. 10.4061/2010/528474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]