Abstract

Background & Aims:

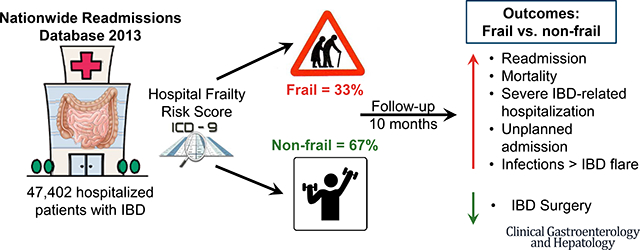

Old age must be considered in weighing the risks of complications vs benefits of treatment for patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). We conducted a nationally representative cohort study to estimate the independent effects of frailty on burden, costs, and causes for hospitalization in patients with IBD.

Methods:

We searched the Nationwide Readmissions Database to identify 47,402 patients with IBD, hospitalized from January through June 2013 and followed for readmission through December 31, 2013. Based on a validated hospital frailty risk scoring system, 15,507 patients were considered frail and 31,895 were considered non-frail at index admission. We evaluated the independent effect of frailty on longitudinal burden and costs of hospitalization, inpatient mortality, risk of readmission and surgery, and reasons for readmission.

Results:

Over a median follow-up time of 10 months, adjusting for age, sex, income, comorbidity index, depression, obesity, severity, and indication for index hospitalization, frailty was independently associated with 57% higher risk of mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.57; 95% CI, 1.34–1.83), 21% higher risk of all-cause readmission (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.21; 95% CI, 1.17–1.25), and 22% higher risk of readmission for severe IBD (aHR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.16–1.29). Frail patients with IBD spent more days in the hospital annually (median 9 days; interquartile range, 4–18 days vs median 5 days for non-frail patients; interquartile range, 3–10 days; P<.01) with higher costs of hospitalization ($17,791; interquartile range, $8368–$38,942 vs $10,924 for non-frail patients, interquartile range, $5571–$22,632; P<.01). Infections, rather than IBD, were the leading cause of hospitalization for frail patients.

Conclusions:

Frailty is independently associated with higher mortality and burden of hospitalization in patients with IBD; infections are the leading cause of hospitalization. Frailty should be considered in treatment approach, especially in older patients with IBD.

Keywords: ageing, prognostic, infection, Crohn’s disease, colitis

Graphical Abstract

The illustrations in these slides are the sole property of the AGA and are provided here for use within your CGH graphical abstract only. These illustrations may not be copied or redistributed.

INTRODUCTION

The incidence and prevalence of IBD in older adults is rising; approximately 10–15% of new IBD diagnoses occur in individuals older than 60 years, with incidence rates as high as 18.9 per 100,000.1–3 In addition, it is expected that within the next decade, over 1/3rd of patients with IBD will be older patients.4 Older patients with IBD represent a vulnerable population with higher rates of hospitalization, inpatient mortality, serious infections, and longer length of stay and costs of hospitalization.5–8 While there has been considerable emphasis on identifying patients at high risk for disease-related complications to inform early use of biologic therapy, there has been limited evaluation of factors that inform risk of treatment-related, or extra-intestinal non-IBD complications that may be more relevant to older patients.9–11 Age is an inadequate metric to ascertain risk-benefit trade-offs of different therapies based on underlying risks of disease and treatment complications. As a result, there is considerable practice variability in managing older patients with IBD, with a preponderance of long-term corticosteroid use and limited use of steroid-sparing therapies.12,13

Beyond age, a more comprehensive assessment of biologic reserve and functional status may be more predictive of overall risks of adverse health outcomes. Frailty represents a dynamic state with vulnerability to external and internal stressors, and has been associated with increased risk of hospitalization and mortality in several diseases, although there has been limited assessment of frailty in IBD.14 Recently, Kochar and colleagues identified frailty, measured using the Hospital Frailty Risk Score, as an independent predictor of serious infections in biologic-treated patients with IBD.15

To further understand the impact of frailty on risk of unplanned healthcare utilization in patients with IBD, we conducted a retrospective cohort study in hospitalized adults with IBD. We used the Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) 2013, a longitudinal, nationally representative sample of all-payer hospital inpatient stays from 21 state inpatient databases developed as part of the family of databases developed by Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), to estimate and compare the hospitalization-related burden, costs and causes of hospitalization in frail vs. non-frail patients with IBD.16,17 The presence of frailty was determined using the Hospital Frailty Risk Score, a validated, administrative claims-based frailty risk score for hospitalized patients.18

METHODS

Data Source

The NRD 2013 is a nationally representative longitudinal database developed and maintained by Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) as a partnership among federal, state, and industry stakeholders and sponsored by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).16,17 The database tracks patients from 21 State Inpatient Databases around the country and accounts for 49.3% of the US population, capturing demographical, clinical, and non-clinical variables from community, public, and academic medical centers. The databases tracks patients hospitalized within a state over the course of any single year, and after adjusting for missing patient linkage numbers and overlapping inpatient stays, capture 85% of all discharges. Using this database, we created a retrospective cohort study to compare clinical outcomes between frail vs. non-frail patients hospitalized with IBD.

This study was deemed exempt from Institutional Review Board as the NRD is a publicly available database that contains de-identified patient information. Overall study design with cohort selection, exposure assignment and outcome ascertainment has been summarized in eFigure 1.

Study Population

We included all adults (age ≥18y) admitted with a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis of IBD between January-June 2013, at time of index hospitalization. After the first admission with a discharge diagnosis of IBD, patients were deemed to be ‘at-risk’ for hospitalization and contributed to follow-up time till December 31, 2013 or death. We used the Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9-CM, developed by HCUP, to identify patients with IBD (CCS code 144).19 The CCS for ICD-9-CM, developed by HCUP, is a categorization scheme for diagnoses and procedures that collapses ICD-9-CM’s extensive codes into smaller number of categories that are both clinically meaningful and more useful for presenting descriptive statistics (see Online Supplement).

We excluded patients with: (a) age<18 at time of index hospitalization, (b) index hospitalization between July-December 2013, (c) initial hospitalization for elective surgery (to allow assessment of impact of frailty in medically-treated patients with IBD), (d) transferred from another hospital, (e) missing data for length of hospital stay or (f) missing data on hospital charges for a given admission.

Exposure Assessment

At the time of first hospitalization, patients’ frailty risk score was calculated using the Hospital Frailty Risk Score.18 This frailty score was developed and validated in 1.04 million hospitalized older adults ≥75y, to screen for frailty and identify a group of patients who are at greater risk of adverse outcomes (mortality, readmission, length of stay). This low-cost score based on International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes, can be readily implemented in hospital information systems, and performs as well as existing frailty and risk stratification tools. We translated the ICD-10 codes used in the study to corresponding ICD-9-CM codes (eTable 1) and used them to assign patients into a low frailty risk (frailty risk score <5) (or ‘non-frail’ patients), medium frailty risk (score 5–15), and high frailty risk (score >15). Though the Hospital Frailty Risk Score ranges from 0 to 99, the original validation study defined these cut-offs to create categories that discriminated most strongly between individuals with different outcomes. As high frailty risk population accounted for only 3.1% of the cohort, we combined medium and high frailty risk patients into one exposure category, classified as ‘frail’.

Patient and Hospital Characteristics

For each patient, we examined their age, sex, primary expected payment source (Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, self-pay, and other insurance types), income quartile based on household income of the patient’s zip code, and relevant comorbidities to calculate Charlson’s Comorbidity Index (eTable 2). For each hospitalization, we captured procedures (GI or hepatic procedures such as endoscopy, colonoscopy, paracentesis, etc., and IBD-related procedures), gastrointestinal surgeries (colostomy, ileostomy, small bowel resection, colorectal resection, local excision of large intestine lesion, etc.), and clinical events (blood transfusions, and parenteral or enteral nutrition) (eTable 3). For each hospital, we examined hospital location, teaching status, and bed size (small, medium, large).

Outcomes

Our co-primary outcomes of interest were risk of inpatient mortality, and readmission after discharge from index hospitalization. Secondary outcomes of interest included: (a) annual burden of hospitalization (total number of days spent in hospital in 2013), (b) annual costs of hospitalization (total costs of hospitalization in 2013, calculated by multiplying charges for each hospitalization with the cost-to-charge ratios for each hospital for 2013), (c) need for IBD-related surgery, (d) severe IBD-related readmission (length of stay >7 days or need for IBD-related surgery), (e) unplanned hospitalization and (f) preventable admission. Preventable hospital admissions were characterized using ICD-9 codes for Prevention Quality Indicators (PQIs), which are a set of measures, developed by AHRQ, that can be used with hospital inpatient discharge data as a “screening tool” to identify ambulatory conditions for which high-quality, community-based outpatient care can potentially prevent hospitalization, complications, or more severe disease (eTable 4).

In addition, we categorized causes for hospitalizations as cardiac, cerebrovascular, respiratory, infections, genitourinary, gastrointestinal (divided into IBD-related vs. non-IBD gastrointestinal causes), endocrine/metabolic, neuropsychiatric, malignancies, fractures, thromboembolism, inflammatory bowel disease specific, and others based on primary CCS diagnosis codes (eTable 5 and eTable 6).

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to compare patient demographics, admission characteristics, and hospital characteristics for the index hospitalization for frail vs. non-frail patients with IBD. We used Pearson χ2 test to analyze categorical variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variables. Categorical variables are expressed as percentages and continuous variables as median with an interquartile range (IQR). All hypothesis testing was performed using a two-sided p-value with a statistical significance threshold <0.05. To evaluate the effect of independent effect of frailty on longitudinal outcomes, we performed multivariable Cox proportional hazard analysis using backward variable selection, adjusting for: age, sex, obesity, household income and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score (based on smoking, obesity, anemia, congestive heart failure, chronic lung disease, depression, diabetes, hypertension, coagulation disorder, liver disorder, electrolyte abnormalities, peripheral vascular disease, psychoses, chronic pain and renal failure).20 Additionally, we performed analysis stratified by patients without any significant comorbidities (CCI score 0) and patients with comorbidities (CCI 1 or more). Post-hoc, based on reviewers’ comments, we updated the multivariable analysis, additionally adjusting for length of stay at index admission, and reason for index admission (IBD-related vs. non-IBD related). All statistical analyses were performed with Stata MP (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

RESULTS

Out of 14,325,172 discharge records analyzed in NRD 2013, 94,498 records were identified for analysis, representing 47,402 unique patients with index hospitalizations between January-June 2013 with a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis of IBD. Of these, 31,895 patients (67.2%) were classified as non-frail and 15,507 patients (32.7%) were classified as frail (14,027 patients classified as having medium and 1,480 as high frailty risk). As compared to non-frail patients, patients with frailty were older, female, had higher burden of comorbidities, and longer length of stay at time of index hospitalization (when their frailty status was assessed) (Table 1). Claims codes within the hospital frailty risk score that were most frequently represented in our cohort were: ‘disorders of fluid electrolyte and acid-base balance’ (47.8% patients), ‘Other and unspecified anemias’ (24.7% patients), ‘Personal history of certain other diseases’ (13.4% patients), ‘Acute renal failure’ (11.5% patients) and ‘Chronic kidney disease’ (9.4% patients).

Table 1.

Patient-, hospital- and hospitalization- characteristics of frail vs. non-frail patients with IBD at time of index hospitalization

| Characteristics at time of index hospitalization | Non-frail patients (N = 31895) | Frail patients (N = 15507) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 49.2 ± 18.5 | 61.9 ± 18.2 | <0.01 |

|

| |||

| Age by categories | |||

| • Age <40 years of age | 36.1% | 14.1% | |

| • Age 40–64 years of age | 39.5% | 35.4% | <0.01 |

| • >64 years of age | 24.4% | 50.5% | |

|

| |||

| Female (%) | 55.7% | 60.0% | <0.01 |

|

| |||

| Urban (%) | 92.4% | 91.5% | <0.01 |

|

| |||

| Primary expected payer (%) | |||

| 1. Medicare/Medicaid | 43.6% | 69.2% | |

| 2. Private insurance | 45.6% | 24.0% | <0.01 |

| 3. Self-pay | 5.5% | 3.49% | |

| 4. No charge/others | 5.3% | 3.29% | |

|

| |||

| Median household income | |||

| 1. 0–25th percentile ($1 – $37,999) | 21.9% | 23.4% | |

| 2. 26th to 50th percentile ($38,000 – $47,999) | 24.9% | 26.5% | <0.01 |

| 3. 51st to 75th percentile ($48,000 – $63,999) | 26.3% | 25.4% | |

| 4. 76th to 100th percentile ($64,000 or more) | 27.0% | 24.8% | |

|

| |||

| Teaching status (%) | |||

| 1. Metropolitan non-teaching | 39.6% | 43.6% | |

| 2. Metropolitan teaching | 52.8% | 47.9% | <0.01 |

| 3. Non-metropolitan | 7.6% | 8.5% | |

|

| |||

| Bed-size (%) | |||

| 1. Small | 10.4% | 10.6% | |

| 2. Medium | 23.3% | 23.8% | 0.28 |

| 3. Large | 67.3% | 65.6% | |

|

| |||

| Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity Index (%) | |||

| • 0 | 69.1% | 41.8% | |

| • 1 | 17.6% | 20.3% | <0.01 |

| • 2 or more | 13.3% | 37.9% | |

|

| |||

| IBD-related procedures (%)2 | 34.3% | 30.4% | <0.01 |

|

| |||

| IBD-related surgery (%)3 | 0 | 0 | |

|

| |||

| Length of stay (unadjusted by month of follow-up) | |||

| • Median | 3 | 5 | <0.01 |

| • IQR | 2–5 | 3–9 | |

|

| |||

| Proportion with severe IBD hospitalization (LOS >7 days OR surgery) (%) | 11.6% | 32.3% | <0.01 |

|

| |||

| Unplanned hospitalization (%) | 77.8% | 91.1% | <0.01 |

|

| |||

| Preventable hospitalization4 (%) | 5.3% | 11.7% | <0.01 |

Longitudinal outcomes in frail vs. non-frail patients

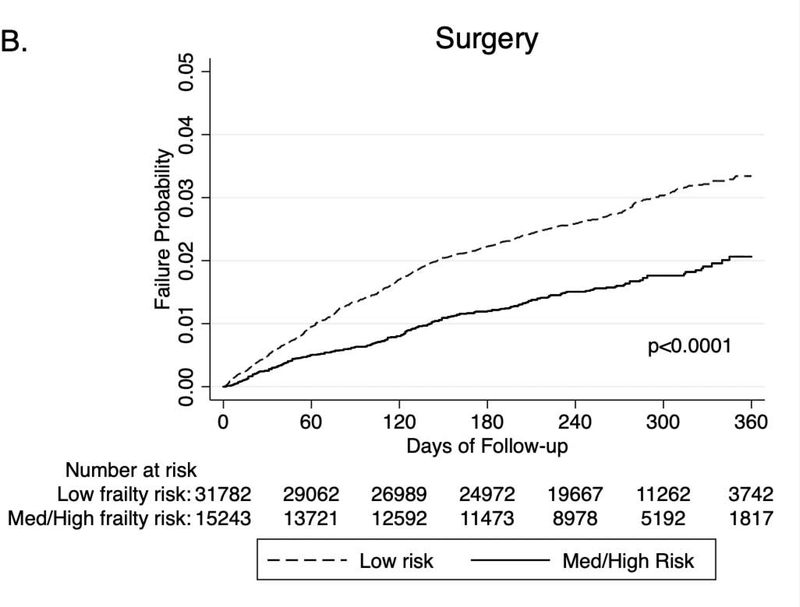

Patients were followed over median 10m after index hospitalization. Patients with IBD with frailty had significantly higher rate of readmission within 6 months (41.2% vs. 33.2% p<0.01), inpatient mortality (2.6% vs 0.7%, p<0.01), risk of severe hospitalizations (15.4% vs. 10.4%, p<0.01) and unplanned hospitalization (37.6% vs. 28.3%, p<0.01), as compared to non-frail IBD patients (Table 2). Frail patients were also less likely to undergo IBD-related surgery (1.04% vs. 2.02%, p<0.01), although no differences were observed in risk of IBD-related procedures (13.5% vs 14.1%, p=0.11), as compared to non-frail patients. Frail patients also had a shorter time to readmission, inpatient mortality and severe hospitalization as compared to non-frail patients (Figures 1A–C).

Table 2.

Longitudinal hospitalization-related outcomes in patients with IBD, based on frailty risk score.

| Outcomes during follow-up | Non-frail patients (N = 31895) | Frail patients (N = 15507) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes within 6m of index hospitalization | |||

| Readmission (%) | 33.2% | 41.2% | <0.01 |

| Inpatient mortality (%) | 0.70% | 2.60% | <0.01 |

| Severe hospitalization (length of stay >7 days or need for IBD-related surgery) (%) | 10.4% | 15.4% | <0.01 |

| Unplanned hospitalization (%) | 28.3% | 37.6% | <0.01 |

| Preventable hospitalization (%) | 3.6% | 7.7% | <0.01 |

| IBD-related Procedures (%) | 14.1% | 13.5% | 0.106 |

| IBD-related Surgery (%) | 2.02% | 1.04% | <0.01 |

| Annual burden and costs of hospitalization | |||

| Total follow-up time (months), median (IQR) | 10 (7–11) | 10 (8–11) | <0.01 |

| Annual days spent in the hospital (including during index hospitalization), median (IQR) | 5 (3–10) | 9 (4–18) | <0.01 |

| Annual costs across all hospitalizations (in dollars), median (IQR) | 10924 (5571 – 22632) | 17791 (8368 – 38942) | <0.01 |

Figure 1.

Longitudinal outcomes in frail vs. non-frail patients with IBD, after index hospitalization: (A) Readmission, (B) Inpatient mortality, (C) severe hospitalization (length of stay >7d or need for IBD-related surgery), (D) IBD-related surgery

On multivariable analysis, adjusting for age, sex, household income, CCI score, obesity, depression, length of stay and reason for index admission, frailty was independently associated with 21% higher risk of readmission (aHR, 1.21 [95% CI, 1.17–1.25]) (Table 3), 57% higher risk of mortality (aHR, 1.57 [1.34–1.83]) (Table 4) and 22% higher risk of IBD-related severe hospitalization (aHR, 1.22 [1.16–1.29]). Frailty was also independently associated with 22% lower risk of IBD-related surgery (aHR, 0.78 [0.66–0.91]) (eTable 7). This independent impact of frailty on risk of readmission, inpatient mortality, and severe hospitalization was observed on several stratified analyses: patients with vs. without significant comorbidities (CCI 1 or more vs. CCI=0), patients with severe vs. non-severe index hospitalization, and patients with index hospitalization due to IBD vs. not related to IBD (eTable 8).

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazard analysis evaluating risk of READMISSION by frailty risk score

| Variable | Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Frailty risk score (mod/high vs low) | 1.21 (1.17 – 1.25) | <0.01 |

|

| ||

| Age (per 1y increase) | 0.99 (0.99 – 0.99) | <0.01 |

|

| ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (reference group: 0) | ||

| • 1 | 1.24 (1.20 – 1.30) | <0.01 |

| • 2 or more | 1.66 (1.60 – 1.72) | <0.01 |

|

| ||

| Length of stay at index hospitalization (per 1-day increase) | 1.01 (1.00 – 1.01) | <0.01 |

|

| ||

| Gender (women vs men) | 0.98 (0.95 – 1.01) | 0.16 |

|

| ||

| Obese (yes vs. no) | 0.95 (0.91 – 1.00) | 0.06 |

|

| ||

| Depression (yes vs. no) | 1.19 (1.14 – 1.24) | <0.01 |

|

| ||

| Median household income (per quartile increase) | 0.96 (0.94 – 0.97) | <0.01 |

|

| ||

| Reason for index hospitalization (IBD vs. non-IBD) | 1.18 (1.14 – 1.22) | <0.01 |

Table 4.

Cox proportional hazard analysis evaluating risk of INPATIENT MORTALITY by frailty risk score

| Variable | Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Frailty risk score (mod/high vs low) | 1.57 (1.34 – 1.83) | <0.01 |

|

| ||

| Age (per 1y increase) | 1.02 (1.02 – 1.03) | <0.01 |

|

| ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (reference group: 0) | ||

| • 1 | 2.71 (2.09 – 3.53) | <0.01 |

| • 2 or more | 7.86 (6.30 – 9.81) | <0.01 |

|

| ||

| Length of stay (per 1-day increase) | 1.02 (1.01 – 1.02) | <0.01 |

|

| ||

| Gender (women vs men) | 0.89 (0.77 – 1.02) | 0.11 |

|

| ||

| Obese (yes vs. no) | 0.70 (0.52 – 0.92) | 0.01 |

|

| ||

| Depression (yes vs. no) | 0.70 (0.55 – 0.88) | <0.01 |

|

| ||

| Median household income (per quartile increase) | 1.05 (0.98 – 1.12) | 0.14 |

Reason for index hospitalization (IBD-related vs. non-IBD-related) was removed due to p>0.2

Annual burden and costs of hospitalization by frailty status

Patients with IBD with frailty spent more days in the hospital annually as compared to non-frail patients (median [IQR]: 9 days [4–18] vs. 5 days [3–10], p<0.01) and had higher annual costs of hospitalization ($17,791 [8,368–38,942] vs. $10,924 [5,571–22,632], p<0.01) (Table 2). Averaged over total follow-up time, frail patients spent more days in hospital per month (0.9 days/m [0.44–1.9] vs 0.5 days/m [0.27–1.0], p<0.01), with higher monthly cost of hospitalization ($1882/m [886–4008] vs. $1158/m [595–2376]).

Reasons for hospitalization by frailty status

Across all hospitalizations, frail patients with IBD were significantly less likely to be hospitalized primarily for gastrointestinal symptoms (14.3% vs. 20.7%, p<0.01), or specifically for IBD flare (14.8% vs. 30.9%, p<0.01). However, frail patients were significantly more likely to be hospitalized for serious infections (21.0% vs. 7.1%, p<0.01), and for respiratory causes (7.7% vs. 4.9%, p<0.01) or fractures (1.9% vs. 0.9%, p<0.01) (Figure 2). Overall, frail patients with IBD were significantly more likely than non-frail IBD patients to experience preventable admissions (27.5% vs. 14%, p<0.01).

Figure 2.

Causes for hospitalization in frail vs. non-frail patients with IBD

DISCUSSION

As the prevalence of IBD increases in older patients, treatment options improve patient longevity, and extra-intestinal manifestations compromise overall health status, it is imperative to identify patients who may be at high risk of disease- vs. treatment-related complication risks. In this nationally representative longitudinal study using NRD, which captures over 85% of all hospital discharges in 21 states, and the validated Hospital Frailty Risk Score, we made several key observations regarding the prognostic impact of frailty in hospitalized adults with IBD. First, we observed approximately 1/3rd of hospitalized adults with IBD may be classified as frail. As anticipated, frail patients were older and had a higher burden of comorbidities. However, approximately half the patients classified as frail were younger than 65y old, and 42% did not have any significant comorbidities. This helps to highlight a distinct profile of frail patients. Second, we observed that frailty was independently associated with a significantly higher burden and costs of hospitalization, risk of readmission and inpatient mortality, even after adjustment for age, comorbidities, and severity and indication for index admission. Third, the most common reason for readmission in frail patients with IBD was infection-related, or related to cardiorespiratory compromise, in contrast to a higher burden of IBD-related hospitalization in non-frail patients with IBD. Frail patients were also likely to undergo IBD-related surgery, though no differences were observed in rates of IBD-related endoscopic procedures. Overall, these findings suggest higher burden of hospitalization and mortality in frail patients with IBD, that may be driven by treatment-related or non-IBD-related complications. Frailty can serve as an important prognostic factor in risk-stratifying patients with IBD, and inform optimal treatment approach.

Several studies have identified that older age is independently associated with higher risk of serious infections, hospitalization and intolerance to immunosuppressive agents in patients with IBD.5–8, 21 Yet, other studies have suggested that selective use of an algorithmic treatment step-up strategy in older patients with suboptimal disease control may be safe and effective in decreasing treatment disutility and avoid persistence on chronic corticosteroids.22 This suggests that chronological age is not an ideal metric to inform treatment approach. On the other hand, frailty, characterized by a decline in functioning across multiple physiological systems, accompanied by an increased vulnerability to stressors, has been more consistently associated with adverse health outcomes across a spectrum of conditions. Frailty has been associated with higher mortality, hospitalization and disability in the general population, and specifically with adverse outcomes following kidney and liver transplantation and elective and emergency surgery.14, 23–27 Frailty has not been well-studied in patients with IBD to date. In a systematic review, Asscher and colleagues highlighted that comprehensive geriatric assessment, including frailty assessment, was often not performed in older patients with IBD.28 In a recent electronic health record-based study in immunosuppressive-treated patients with IBD, Kochar and colleagues observed that pre-treatment frailty assessed using a similar code-based algorithm was present in ~12% patients, and was associated with 1.8–2.0-fold higher risk of serious infections in these patients.15 The prevalence of frailty rates was higher in our cohort, which may be due to differences in patient population – we focused only on hospitalized adults with IBD. Nonetheless, we confirmed their observation that frail patients with IBD are more likely to be hospitalized for serious infections, rather than for direct disease-related complications.

We focused on relatively short-term outcomes after a diagnosis of frailty. This was, in part, a limitation inherent to the database, which only tracks patients longitudinally within a calendar year. However, it is also important to recognize that frailty is a dynamic state, arising due to dysregulated, often interconnected, stress response, across immune, endocrine and energy response systems, and may occur even in absence of a clear disease state or due to failure to rebound following illness or hospitalization. Frailty may be mitigated or possibly prevented through targeted interventions such as precise physical rehabilitation strategies, nutritional counseling and supplementation and cognitive training.29, 30 Hence, attributing long-term adverse health outcomes after a one-time diagnosis of “frailty” may be challenging, and better analyzed through repeated measures of frailty.

The strengths of our study include (a) innovative use of a nationally representative database, which was designed for the study of readmission risk and hospital-related outcomes (b) comprehensive implementation of validated code-based frailty risk score algorithm to identify patients at low-, medium- and high-risk of frailty, (c) thorough evaluation of multiple adverse health outcomes around unplanned healthcare utilization, adjusting for important confounders, and (d) assessment of reasons for hospitalizations, including preventable and non-preventable admissions. While our study draws its strength from a large sample of patients that were longitudinally followed over the course of a year, it has some limitations. First, all analyses are based on administrative codes and CCS, which have inherent limitations both with regard to misclassification of IBD diagnosis (especially in older patients), as well as with regard to causes of admissions. Second, in using the Hospital Frailty Risk Score, we combined patients at medium to high risk of frailty, and classified them as frail. Frailty status was determined cross-sectionally, at a single time point. Frailty is a dynamic, multi-domain concept, encompassing somatic, mental, functional and social status, that extends along a spectrum, rather than being binary.31 Future prospective studies would focus on examining all these domains of frailty, repeatedly over time, and evaluate its evolution and impact on adverse health outcomes in patients with IBD. Third, our analyses only focused on hospitalized patients, without details of outpatient clinic visits, medication use, and subjective and objective disease activity assessment, which may more comprehensively explain the differential outcomes observed between frail and non-frail IBD patients. Fourth, causes of readmissions were based on primary discharge diagnoses and grouped by system for ease of interpretation, which could result in potential misclassification and be somewhat biased due to reimbursement practices. Fifth, though the frailty risk scoring codes include physical function components, such as hemiplegia, abnormal gait, fracture, and care involving rehabilitation procedures, no objective physical performance measures were assessed. Finally, NRD is inherently limited since it captures admissions only within state boundaries, is limited to one calendar year, and does not capture out-of-hospital mortality.

In summary, we observed that frailty is prevalent in approximately 1/3rd hospitalized adults with IBD. Frail patients have significantly higher burden and costs of hospitalization, higher risk of unplanned and preventable hospitalizations, and higher in-hospital mortality. Infections, rather than IBD-related causes, are the leading cause of hospitalization in frail patients. Future prospective studies incorporating routine assessment of multiple domains of frailty using validated scales, objective sarcopenia and physical function measurement, and eventual rehabilitation intervention to prevent or treat frailty, are warranted to better inform the impact of frailty, and it’s treatment, in the management of patients with IBD.

Supplementary Material

eFigure 1. Study design with cohort selection, exposure assignment and outcome ascertainment.

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW.

Background

Age is an inadequate metric to ascertain risks vs benefits of treatments for inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). Assessment of biologic reserve and functional status might be better for determining overall risk of adverse outcome.

Findings

In a nationally representative cohort study of 47,402 hospitalized patients with IBD (33% frail), frailty, measured using a validated hospital frailty risk score, was associated with a higher subsequent risk of mortality, readmission, and annual burden and costs of hospitalization. Infections, rather than IBD, were the leading cause of hospitalization in frail patients.

Implications for Patient Care

Frailty is an important prognostic factor for patients with IBD and should be considered in selection of treatment.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: Dr. Nguyen is supported by NIH/NIDDK (T32DK007202). Dr. Sandborn is partially supported by NIDDK-funded San Diego Digestive Diseases Research Center (P30 DK120515). Dr. Singh is supported by NIH/NIDDK (K23DK117058), IOIBD Operating Grant 2019 and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation Career Development Award (#404614).

WJS – research grants from Atlantic Healthcare Limited, Amgen, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Abbvie, Janssen, Takeda, Lilly, Celgene/Receptos,Pfizer, Prometheus Laboratories (now Prometheus Biosciences); consulting fees from Abbvie, Allergan, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Avexegen Therapeutics, BeiGene, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Celltrion, Conatus, Cosmo, Escalier Biosciences, Ferring, Forbion, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Gossamer Bio, Incyte, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin Pharmaceutical Research, Landos Biopharma, Lilly, Oppilan Pharma, Otsuka, Pfizer, Progenity, Prometheus Biosciences (merger of Precision IBD and Prometheus Laboratories), Reistone, Ritter Pharmaceuticals, Robarts Clinical Trials (owned by Health Academic Research Trust, HART), Series Therapeutics, Shire, Sienna Biopharmaceuticals, Sigmoid Biotechnologies, Sterna Biologicals, Sublimity Therapeutics, Takeda, Theravance Biopharma, Tigenix, Tillotts Pharma, UCB Pharma, Ventyx Biosciences, Vimalan Biosciences, Vivelix Pharmaceuticals; and stock or stock options from BeiGene, Escalier Biosciences, Gossamer Bio, Oppilan Pharma, Prometheus Biosciences (merger of Precision IBD and Prometheus Laboratories), Progenity, Ritter Pharmaceuticals, Ventyx Biosciences, Vimalan Biosciences. Spouse: Opthotech - consultant, stock options; Progenity - consultant, stock; Oppilan Pharma - employee, stock options; Escalier Biosciences - employee, stock options; Prometheus Biosciences (merger of Precision IBD and Prometheus Laboratories) - employee, stock options; Ventyx Biosciences – employee, stock options; Vimalan Biosciences – employee, stock options.

SS – research grants from AbbVie, Janssen

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

ASQ – None to declare

NHN – None to declare

JE – Team Leader of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Physical Therapy, and Exercise Clinical Practice Guideline Team.

LOM – None to declare

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gisbert JP, Chaparro M. Systematic review with meta-analysis: inflammatory bowel disease in the elderly. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39:459–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh S, Underwood F, Loftus EV, et al. Worldwide Incidence of Older-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in the 21st Century: A Systematic Review of Population-Based Studies. Gastroenterology 2019;156:S394–S395. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global Burden of Diseases Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;5:17–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coward S, Clement F, Benchimol EI, et al. Past and Future Burden of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Based on Modeling of Population-Based Data. Gastroenterology 2019;156:1345–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ananthakrishnan AN, McGinley EL, Binion DG. Inflammatory bowel disease in the elderly is associated with worse outcomes: a national study of hospitalizations. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009;15:182–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brassard P, Bitton A, Suissa A, et al. Oral corticosteroids and the risk of serious infections in patients with elderly-onset inflammatory bowel diseases. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:1795–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cottone M, Kohn A, Daperno M, et al. Advanced age is an independent risk factor for severe infections and mortality in patients given anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9:30–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen NH, Ohno-Machado L, Sandborn WJ, Singh S. Infections and Cardiovascular Complications Are Common Causes for Hospitalization in Older Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2018;24:916–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ha CY, Katz S. Clinical implications of ageing for the management of IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;11:128–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh S, Picardo S, Seow CH. Management of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in Special Populations: Obese, Old, or Obstetric. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;18:1367–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ananthakrishnan AN, Donaldson T, Lasch K, et al. Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the Elderly Patient: Challenges and Opportunities. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017;23:882–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benchimol EI, Cook SF, Erichsen R, et al. International variation in medication prescription rates among elderly patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2013;7:878–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waljee AK, Wiitala WL, Govani S, et al. Corticosteroid Use and Complications in a US Inflammatory Bowel Disease Cohort. PLoS One 2016;11:e0158017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoogendijk EO, Afilalo J, Ensrud KE, et al. Frailty: implications for clinical practice and public health. Lancet 2019;394:1365–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kochar B, Cai W, Cagan A, et al. Pre-treatment Frailty Is Independently Associated With Increased Risk of Infections After Immunosuppression in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology 2020;158:2104–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Overview H. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Overview N. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD., 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilbert T, Neuburger J, Kraindler J, et al. Development and validation of a Hospital Frailty Risk Score focusing on older people in acute care settings using electronic hospital records: an observational study. Lancet 2018;391:1775–1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elixhauser APL. Clinical Classifications Software (CCS): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Volume 2017. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borren NZ, Ananthakrishnan AN. Safety of Biologic Therapy in Older Patients With Immune-Mediated Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:1736–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh S, Stitt LW, Zou G, et al. Early combined immunosuppression may be effective and safe in older patients with Crohn’s disease: post hoc analysis of REACT. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019;49:1188–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Handforth C, Clegg A, Young C, et al. The prevalence and outcomes of frailty in older cancer patients: a systematic review. Ann Oncol 2015;26:1091–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hewitt J, Long S, Carter B, et al. The prevalence of frailty and its association with clinical outcomes in general surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2018;47:793–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kallenberg MH, Kleinveld HA, Dekker FW, et al. Functional and Cognitive Impairment, Frailty, and Adverse Health Outcomes in Older Patients Reaching ESRD-A Systematic Review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;11:1624–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim DH, Kim CA, Placide S, et al. Preoperative Frailty Assessment and Outcomes at 6 Months or Later in Older Adults Undergoing Cardiac Surgical Procedures: A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med 2016;165:650–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kobashigawa J, Dadhania D, Bhorade S, et al. Report from the American Society of Transplantation on frailty in solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant 2019;19:984–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asscher VER, Lee-Kong FVY, Kort ED, et al. Systematic Review: Components of a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment in Inflammatory Bowel Disease-A Potentially Promising but Often Neglected Risk Stratification. J Crohns Colitis 2019;13:1418–1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dent E, Martin FC, Bergman H, et al. Management of frailty: opportunities, challenges, and future directions. Lancet 2019;394:1376–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Negm AM, Kennedy CC, Thabane L, et al. Management of Frailty: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2019;20:1190–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asscher V, Jong AVM, Mooijaart S. The Challenges of Managing Inflammatory Bowel Diseases in Older Patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;18:1648–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Study design with cohort selection, exposure assignment and outcome ascertainment.