Abstract

Abstract

Hypopharyngeal tissue engineering is increasing rapidly in this developing world. Tissue damage or loss needs the replacement by another biological or synthesized membrane using tissue engineering. Tissue engineering research is emerging to provide an effective solution for damaged tissue replacement. Polyurethane in tissue engineering has successfully been used to repair and restore the function of damaged tissues. In this context, Can polyurethane be a useful material to deal with hypopharyngeal tissue defects? To explore this, here ester diol based polyurethane (PU) was synthesized in two steps: firstly, polyethylene glycol 400 (PEG 400) was reacted with lactic acid to prepare ester diol, and then it was polymerized with hexamethylene diisocyanate. The physical, mechanical, and biological testing was done to testify the characterization of the membrane. The morphology of the synthesized membrane was investigated by using field emission scanning electron microscopy. Functional groups of the obtained membrane were characterized by fourier transform infrared spectroscopy spectroscopy. Several tests were performed to check the in vitro and in vivo biocompatibility of the membrane. A highly connected homogeneous network was obtained due to the appropriate orientation of a hard segment and soft segment in the synthesized membrane. Mechanical property analysis indicates the membrane has a strength of 5.15 MPa and strain 124%. The membrane showed high hemocompatibility, no cytotoxicity on peripheral blood mononuclear cell, and susceptible to degradation in simulated body fluid solution. Antimicrobial activity assessment has shown promising results against clinically significant bacteria. Primary hypopharyngeal cell growth on the PU membrane revealed the cytocompatibility and subcutaneous implantation on the back of Wistar rats were given in vivo biocompatibility of the membrane. Therefore, the synthesized material can be considered as a potential candidate for a hypopharyngeal tissue engineering application.

Graphic abstract

Keywords: Polyurethane, Tissue engineering, Hypopharyngeal, Cancer, Membrane

Introduction

Acute disease, trauma, and accident are the leading cause of tissue loss, which is the crux of the health, as tissue replacement is expensive and limited to suitable compatibility [1]. Tissue engineering is the most promising scientific approach to develop appropriate biological materials that help in tissue replacement and reconstruction [2, 3]. Day by day, these techniques are manifested with excellent biocompatibility along with an economical point of view [4]. Materials that exhibit right physical, chemical, mechanical, and biological properties are conferred as a suitable and potent candidate for tissue engineering applications such as polymer [5]. As a material, a polymer is valued in terms of extensive biocompatibility towards different areas of biomedical applications [6]. Numerous natural and synthetic polymers are extensively used in materials research such as collagen, polyamide, chitosan, and polyester etc. Most of the polymers can’t show healthy tissue like characteristics. Thus, several extensive tissue-specific processing is required to meet the maximum characteristic properties and mimic the behavior of natural tissue [7].

Nowadays, Polyurethane is rapidly used in tissue engineering and biomaterial research [8]. Polyurethane can be of different types, such as polyester urethane, polyether urethane, polycarbonate urethane. Among different polyurethane, polyester urethane and polyether urethane consist of ester or ether group, respectively, shows biodegradation [9]. Several studies reveal that polyester urethane is more apt for biodegradation than polyether urethane [10]. Polyester urethane can get hydrolytically degraded in a phosphate buffer solution of pH 7.4 at 37 °C, which reduces more weight as the higher concentration availability of lactic acid [11]. Besides, polyethylene glycol (PEG) is incorporated in polyurethane synthesis because of its excellent biocompatibility and biodegradability [12, 13]. Various isocyanate has been extensively used in polyurethane synthesis like 1,4 butane diisocyanate (BDI), 4,4-methylene diphenyl diisocyanate (MDI), 1,6-hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI) etc. [14]. Among different isocyanates, HDI has a simple aliphatic chain, which is the main reason behind its biocompatible nature.

In the soft tissue engineering, membrane with high strength and elasticity are necessary mostly with controllable biodegradation property. Polymeric materials with high biocompatibility have been extensively used for fabricating living tissue construct [15, 16]. Soft tissue like hypopharynx or simply hypopharyngeal tissue comes on research due to various recent cases of hypopharyngeal cancer. Hypopharynx is the portion between the esophageal inlet and oropharynx [17]. Hypopharynx receives the arterial supply from superior and inferior thyroid arteries. It is basically the space from the plane perpendicular tip of the epiglottis to the superior and lateral aspect of the larynx. It includes the structure of lateral pharyngeal walls, including mucosal membrane and bilateral pyriform sinus [18, 19]. Literature had shown that high consumption of alcohol and tobacco abuse rapidly increases the chance of hypopharyngeal cancer. This cancer starts in the squamous cell layer refers to squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinoma of hypopharynx represents a clinical significance among the other types of neck cancer. Initially, this cancer starts at hypopharynx and gradually spread in related tissue, including the thyroid gland, and trachea [20]. Surgery is the most well-known approach for this treatment by the removal of affected tissue of the pharynx and replaces with other tissue like a flap. But this may lead to tissue defects, voice handicaps, including the loss of swallowing capability [21, 22]. Therefore, to overcome such complications, tissue engineering comes in this place to synthesis the biomaterial in the form of a matrix that could help to repair the tissue defects.

In this study, Polyester urethane was synthesized using PEG and HDI with a suitable composition. Its morphological, physicochemical, and mechanical characteristics were studied by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), and UTM mechanical testing machine respectively. Biological properties were analyzed like hemocompatibility, antimicrobial assay, and MTT (3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay. Further, In vitro compatibility was checked through primary hypopharyngeal fibroblast culture on the membrane, immunofluorescence staining for analysis of fibroblast growth, and cytocompatibility analysis through mitochondrial activity check by MTT assay. The material was subcutaneously implanted into the back of wister rats in order to assay the material’s in vivo biocompatibility.

Materials and methods

Materials

Lactic acid and polyethylene glycol were purchased from LOBA Chemic Pvt Ltd. and Merck life science Pvt Ltd. respectively. Hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI) and dibutyltin dilaurate (DBTDL) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich India. Benzene was bought from Merck Life Science Pvt Ltd.

Preparation of ester diol

Lactic acid (LA) and Polyethylene glycol (PEG 400) were reacted in the presence of catalyst sulfuric acid to produce the ester diol. The reaction was allowed to take place with molar ration 2:1 (PEG 400: LA) in a round bottom flask. Benzene was used as a solvent at 50 wt% of the reactant in this reaction. The reaction was maintained at temperature 80 °C for 14 h. By using vacuum distillation, light yellowish colour viscous ester diol was collected, which was further used for polyurethane synthesis.

Polyurethane (PU) synthesis

PU was synthesized by reacting Hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI) with previously prepared ester diol in 2:1 (NCO: OH) molar ratio. Tetrahydrofuran (THF) at 50 wt% of the reactant was used as a solvent, and dibutyltin dilaurate (DBTDL, 0.05 wt%) was added as a catalyst in this reaction. The reaction was maintained under controlled stirring for 2 h at room temperature. Finally, the viscous polyurethane was cast on to a glass petri dish and kept for solvent removal by placing at room temperature for 24 h followed by 80 °C heat treatment in an oven for 5 h.

Field emission scanning electron microscopy study

The surface morphology of the polyurethane membrane was studied by using field emission scanning electron microscopy (Hitachi S2700). The polyurethane membrane was cut in small round pieces and coated with gold for the surface analysis. FESEM was taken at suitable magnification with an accelerating voltage of 5 kV.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy study

Structural and functional groups of polyurethane membranes were studied by using the FTIR spectrum (Nicolet Megna IR760 Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy) analysis. The synthesized polyurethane membrane was boiled in distilled water at 50 °C for removal of residual solvent and kept at a vacuum desiccator for 24 h. The polyurethane membrane was cut in small round pieces for FTIR analysis with a frequency range 4500–500 cm−1 and resolution of 4 cm−1.

Mechanical property study

A Hounsfield UTM machine (UTE-60, ASI UTM Machine) was used to check the mechanical property of the membrane. After synthesis, the membrane was cut into a dumbbell-shaped form (0.5 mm × 2 mm) for the mechanical property analysis such as tensile strength, specific tensile strength, and elongation at break.

Degradation study

Small round pieces (2 mm diameter) of the membrane were incubated in simulated body fluid (SBF) solution. After a specific time interval, the swollen membrane was dried in an oven for a period of 24 h at 37 °C. Post degradation weight changes were measured by using Sartorius BP-110 analytic balance. The degradation percentage of each interval time was calculated by using the following formula

here W0 denotes initial weight (mg), Wl denotes final weight (mg) after degradation. The test was performed in triplicate for all the time intervals.

Hemocompatibility study

Fresh blood collected in an EDTA vial (from the first author, collected by Thyrocare Preventive Health Care Lab and Diagnostic Centre with following the clinical guidelines and signed consent from the author) and was diluted in phosphate buffer (0–9%) to prepare the blood sample for hemolysis assay. Small round shape membrane (2 mm diameter) was equilibrated in saline solution for 30 min at 37 °C. Then prepared blood sample was added in an equilibrated solution containing membrane and kept for incubation for 60 min at 37 °C. Diluted blood with Triton X-100 and phosphate buffer solution was used to prepare positive and negative control respectively for the hemocompatibility study. The percentage of hemolysis was computed using the following formula

here OD (test) denotes the value of the sample, OD (positive) denotes the value of positive control, and OD (Negative) denotes the value of negative control. The test was performed in triplicate.

Antimicrobial activity study

The synthesized membrane was cut into small pieces to check the antimicrobial activity against clinically significant bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive), and Escherichia coli (Gram-negative). This study was accomplished using the membrane diffusion (disc diffusion) method to ensure that synthesized biomaterial didn’t induce or promote any growth of microorganisms. Small pieces of polyurethane membranes were placed onto bacterial culture for each bacterium and subjected to incubation overnight at 37 °C.

Immuno-fluorescence staining using primary hypopharyngeal fibroblast

Primary hypopharyngeal fibroblast cells were obtained from the commercial sale of the National Centre for Cell Science, Pune. Fibroblast cells seeded on polyurethane membrane were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 10 min at room temperature followed by washing 3 times in PBS for 5 min for each sample. Then it was soaked in 0.2% Triton X-100 at 37 °C for 15 min, followed by 3 times wash for 5 min for each set. After that, the material was blocked in 10% goat serum (G9023-Sigma-Aldrich, India) at 37 °C for 20 min and placed for overnight incubation in mouse antivimentintin antibody at 4 °C. After overnight incubation, the material (diluted in PBS, 1:200) was washed in PBS 3 times for 5 min for each sample. It was incubated in fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (diluted in PBS, 1:50) at 37 °C for 2 h in a completely dark room. Then it was washed with PBS and was deepening in 4, 6-diamidino 2- pherylindoledihydrochloride (DAPI) solution (prepared in PBS, 3 μg/ml) for 5 min to stain the nuclei (blue fluorescence) [23, 24]. Immuno-florescence was observed under a confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM, Olympus fluo view-800).

MTT assay study

Mitochondrial activity of PBMC- For MTT assay [25, 26], Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from fresh blood and cultured in a complex growth medium containing 88% RPMI (Sigma-Aldrich, India), 10% FBS (F9665-Sigma-Aldrich, India), and 2% antibiotic with 5% CO2 incubation for five days at 37 °C to reach 80% confluency of the monolayer. After that equal amount of cell was placed to a well plate with small round shape biomaterials (1 mm diameter) in triplicate and maintained the growth conditions. After a 24 h incubation period, 0.5 µg of MTT treatment was performed followed by 4 h incubation that produces formazan, which was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) followed by 30 min incubation. Finally, the MTT assay result was evaluated in a well plate reader at 490 nm. One-way ANOVA [24] was performed to evaluate the statistical significance for the outcome at 0.05 level of significance.

Mitochondrial activity of hypopharyngeal fibroblast- Mitochondrial activity was evaluated using the MTT method [27] at the 5th and 10th day of incubation. 100 μl of methylthiazolyldiphenyltetrazodium (MTT solution 0.5 mg/ml) was added into each well of a 96 well plate and culture placed for incubation at 37 °C for 4 h in 5% CO2 incubator. After that, DMSO was added to the well to dissolve the purple formazan, and OD was taken using a well plate reader (Instrument details) at 490 nm. The absorbance was measured for blank, where the same procedure was performed without biomaterial. Similarly, the cells also cultured on the commercially available Mesh (polystyrene mesh), as a positive control. The experiment was conducted in triplicate and was averaged the data for analysis.

In vivo biocompatibility assay

Healthy wistar female rat weight between (150–180 g) was used here. Before starting the experiment, animals were acclimatized to laboratory conditions for 7 days. The animals had resided in polypropylene cage in laboratory conditions, such as temperature 20- 24 °C and a light–dark cycle of 12 h. A standard diet was provided to the Rats with water ad libitum for the entire experiment. Tissue grafting experiment protocol: Materials required- Ethanol, diethyl ether, formaldehyde, Polypropylene tissue reconstruction mesh (LME 66-1). Instruments required- Surgical blade (no 10), surgical needles, suture no 1/10, forceps, 3 scissors. The dorsal far from the rats were removed and the area was cleaned with 70% ethanol. The animals were divided into four groups. Each group contained 3 rats. Group-I was controlled with normal physiological conditions. Group II was challenged with no treatment. Group-III and IV were treated with polypropylene mesh and synthesized polyurethane biomaterial, respectively. Before the incision wound model for tissue grafting, the rats were anesthetized with Ketamine (80 mg/kg body weight) [28]. An incision of a 1 cm long tissue wound was made using a surgical blade (no 10). After the incision, the polyurethane biomaterial and polypropylene mesh were grafted in the tissue wound area, and surgical sutures (no1/10) was applied to close the skin (Fig. 1). After the predetermined time (14 days), the material was explanted with a small amount of surrounding tissue.

Fig. 1.

a–c Subcutaneous implantation to the back of a wistar rat

We followed the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals as described by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Ethical approval was given by the IAEC, Bengal School of Technology, through the granted number 1726/CPCSEA/IAEC/2019-007.

Histopathological examination

Tissue specimens with the biomaterial were fixed in a 10% formalin solution for 1 h. Then the samples were freeze embedded and performed microtome slicing into 4 μm section. It was stained with hematoxylin–eosin stain and finally analyzed under a light microscope [28]. The images were taken by an Olympus camera combined with a microscope.

Statistical analysis

Experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3). The experimental results are depicted as the mean value ± standard deviations (SD). Statistical analysis was done using one-way ANOVA analysis with P < 0.05 considered as statistically significant.

Results and discussion

Polyurethane synthesis

In this synthesis, the ester linkage was incorporated in the backbone of polyurethane. To synthesize polyester urethane, firstly lactic acid (LA) and polyethylene glycol 400 (PEG 400) was reacted in the presence of the catalyst, sulfuric acid. This reaction was continued in a benzene solvent medium for 14 h, and finally, ester diol was collected by vacuum distillation. Finally, this ester diol was reacted with hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI) in the presence of the catalyst, DBTDL, with a molar ratio of NCO: OH equal to 2:1 for ester diol based polyurethane synthesis. Overall ester diol based polyurethane synthesis was done in two steps as follows,

In the first step, a hydroxyl group (OH) of polyethylene glycol (PEG 400) was reacted with a carboxyl group (COOH) of lactic acid in the presence of a few drops of sulfuric acid (H2SO4). Benzene, as a solvent, was used in this esterification reaction for 14 h, which gradually evaporated as an azeotropic mixture with water. Pure ester diol was obtained by vacuum distillation from the reaction mixture of non-reacted reactants present in the flask. Light yellowish colour pure ester diol was collected from the distillation outlet.

In the second step, this ester diol was reacted with hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI) in the presence of DBTDL at room temperature. Longer hard segments were reduced by using an adequate amount of HDI. Similar exercise was found with polyurethane membrane preparation with maintaining a uniform hard segment [29]. Tetrahydrofuran (THF), the solvent medium was used in this reaction for 2 h to get the viscous polyurethane. The viscous polymer was efficiently cast onto the glass petri dish (shown in Fig. 2a) under vacuum conditions to reduce the chance of bubble formation.

Fig. 2.

a Image of casted polyurethane membrane. b Random pieces of synthesized polyurethane membrane

Solvent removal of polyurethane film was initiated by gradual evaporation of solvent from the membrane at atmospheric moisture for 24 h. The synthesized polyurethane membrane was peeled off carefully from the glass plate and subjected to boil in distilled water (20 min) for the removal of residual solvent. Finally, the polyurethane membrane was dried at room temperature and kept in vacuum desiccators until further studies [30]. In Fig. 2b shows the random pieces of ester diol based polyurethane membrane.

Physical and mechanical characterization of materials

Surface topology can effectively influence cellular activity on the membrane [31, 32]. FE-SEM micrograph of polyurethane membrane in Fig. 3 depicts the dense structure. It is clear that highly condensed cross-linking decreases the pore size. From the FESEM results, the expected pore size may be in approx of 0.5 μm. This structure may facilitate cellular migration, proliferation, and nutrient supply as the porosity controls the transfer of water and cellular metabolites [33, 34].

Fig. 3.

FE-SEM micrograph of ester diol based polyurethane

The Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy of ester diol-based polyurethane is shown in Fig. 4. The important peaks are assigned with details in the Table 1. Some typical functional groups of polyester polyurethane were observed in between the frequency range 4500–500 cm−1. Symmetrical stretching of NCO and COC group was observed at 940 cm−1. The band at 1752 cm−1, 1247 cm−1, and 1126 cm−1 may confirm the ester linkage. A small shoulder was seen near 3507 cm−1, which is related to N–H stretching. The peak at 2864 cm−1 and 2948 cm−1 are assigned to the C–H stretching and asymmetric CH2 group, respectively [28, 32]. A strong band is observed at 1730 cm−1, denotes to aliphatic C=O stretching vibration. Segmented polyurethane using HDI–BDO–HDI chain extender represented this property in the long hard segments in the polyurethane. It shows the occurrences of ring-opening copolymerization which is linked with the properties of medical-grade polyurethane [35].

Fig. 4.

FTIR spectra of ester diol based polyurethane

Table 1.

FTIR peak assignment of synthesized polyurethane membrane

| Wave number (cm−1) | Peak assignment |

|---|---|

| 940 | Symmetric stretching of N–CO and C–O–C bonds in polyurethane |

| 1126 | Ester linkage |

| 1247 | Ester linkage |

| 1700 | C=O |

| 1752 | Ester linkage |

| 2864 | C–H stretching |

| 2948 | Asymmetric CH2 stretching |

| 3507 | N–H stretching |

Mechanical characterization clearly explains the adequate strength and stability of polyester diol-based polyurethane. The mechanical behavior of material generally depends on the molecular weight of synthesized polymeric biomaterials [36] for the same polymer. With increase in molecular weight mechanical strength improve for a specific polymer. Here we used low molecular weight lactic acid and polyethylene glycol (PEG 400) for producing low molecular weight ester diol that ultimately reacted with HDI. Thus, it created the membrane little brittle but comparatively soft. Modification of the mole ratio and condition of polymerization alters the molecular weight that significantly changes the membrane’s mechanical properties [1, 9]. Here, the stress–strain curve, which depicts the essential mechanical behavior, is shown in Fig. 5 and detailed in Table 2. The tensile strength and strain were marked at 5.15 ± 0.58 MPa and 124 ± 16.4%, respectively. This finding can explain that the material was more robust than natural polymer collagen (0.31Mpa) [37]. This property withstands the in vivo stimuli and can be able to assist in functionalizing biomolecular group for cell adhesion. This can help to accommodate high-density cells [1]. However, human natural hypopharyngeal tissue showed strength and strain, 7.65 ± 0.24 MPa, and 142 ± 13.1%, respectively, which is relatively stronger than the synthesized membrane [28]. Nevertheless, this information couldn’t validate in the laboratory due to ethical issues with human subjects. Overall analysis showed that this synthesized polyurethane was somewhat soft and less brittle, formed by an aliphatic isocyanate group as a hard domain and polyol as a soft one.

Fig. 5.

Tensile stress–strain curve of ester diol based polyurethane

Table 2.

Physicomechanical property details of ester diol based polyurethane membrane

| Sample details | Density (gm/cc) | Tensile strength (MPa) | Strain % | Elastic modulus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyurethane | 1.09 | 5.15 ± 0.58 | 124 ± 16.4 | 2.9 ± 0.2 |

Degradation property of synthesized polyurethane

Degradation property analysis is a significant benchmark for synthesized polyurethane to estimate weight loss. The property analysis was performed by plotting the weight loss percentage vs time. Weight loss percentage was calculated by the change of weight to the initial weight of the material. The test was performed in vitro over 60 days. The result of a degradation study is shown in Fig. 6. The results depict that initially, the polyurethane membrane was slowly reduced weight up to 10 days (5% approx), then the rate of degradation was increased slightly up to 40 days (17% approx). Finally, on the 60th day, the degradation rate was marked at 22%, which denotes that the material shows significant biodegradability.

Fig. 6.

Degradation plot of polyurethane membrane

Hemocompatibility and cytotoxicity analysis

Hemolysis assay was performed using polyester diol based polyurethane membrane to check the blood compatibility of the synthesized material. The percentage of hemolysis was calculated between the difference of test absorbance and negative control absorbance to the difference between positive and negative control absorbance. The result analysis of this material denotes 0.83% hemolysis, which signifies the material as highly hemocompatible because, as per ASTM (American Society for Testing and Materials), a highly hemocompatible material should show less than 5% hemolysis [38].

In MTT assay, cytotoxicity was an indicator to check whether the synthesized polyurethane membrane shows any kind of toxicity towards cells. Cytotoxicity of polyester diol based polyurethane membrane was done against isolated PBMC (Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell). The result of the cytotoxicity for control and the treated membrane is shown in Fig. 7. One-way ANOVA was performed to check the statistical significance level, which reveals the computed P value 0.179 at 0.05 level significance, and the population mean are not significantly different. It implies that when a small piece of polyurethane membrane was placed in PBMC cell culture, it has not interrupted cellular proliferation.

Fig. 7.

Cytotoxicity analysis of PU membrane (treated group) and control (*represents the statistical significance between control and polyurethane membrane)

Antimicrobial assay significance

The result of the antimicrobial assay is shown in Fig. 8 for E. coli and S. aureus. The result analysis showed a clear zone surrounding the membrane and no growth on the membrane surface. This finding may conclude that this synthesized material doesn’t promote pathogenic bacterial growth and also inhibit them.

Fig. 8.

Antimicrobial assay shows the zone of inhibition surrounding polyurethane membrane

In vitro cytocompatibility

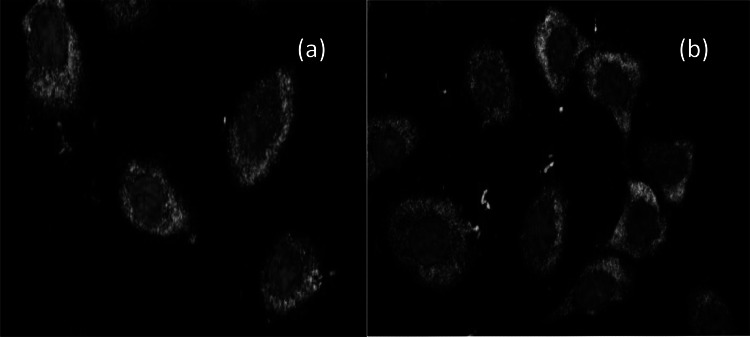

Cytocompatibility of synthesized polyurethane membrane was measured via goat hypopharyngeal fibroblast seeding, where commercial mesh was used as a control. Cells were stained using immune-fluorescent staining to visualize them on the membrane. MTT assay showed that cells grew and proliferated on the membrane.

Vimentin is a reliable fibroblast marker that frequently found intermediate filament in fibroblast [39]. Primary antibody antivimentin was used in which cells on the membrane were immune stained (here green fluorescence) to confirm the fibroblast after 5th and 10th days using in vitro culture, respectively. The fluorescence stained cells were shown in Fig. 9a, b for 5th and 10th days, respectively. These findings indicated that fibroblast cells could grow onto the polyurethane membrane using the in vitro cell culture methodologies. MTT assay on polyurethane membrane was measured against fibroblast cell for 5th day and 10th day, where increased OD value from 5th day to 10th day, indicate the cell proliferation capacity on the membrane. The result of the MTT assay is shown in Fig. 10. The cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 105cells/ml and culture for 5 and 10 days. One-way ANOVA was performed using the value of OD to check the statistical significance, where the P-value was 0.145 and 0.211 at 0.05 significance level and no significant difference with the population mean. This result indicates that fibroblast cells can effectively grow on polyurethane membranes compare to commercial mesh, so the material is as cytocompatible as commercially available mesh.

Fig. 9.

Represents the primary hypopharyngeal fibroblast cell growth on PU membrane a after 5th days and b after 10th days

Fig. 10.

Cytotoxicity check on hypopharyngeal fibroblast cell using MTT assay for synthesized polyurethane membrane and commercialized mesh (*represents the statistical significance between mesh and polyurethane membrane at 5th day, and # denotes the statistical significance between them at 10th day)

In vivo efficiency analysis and histopathological examination

After 7th day it was examined that the material has been degrading and no such tissue level infection in the implanted area, depicts in Fig. 11a. Figure 11b shows the explanted tissue after 14th day and examined that the material was almost completely degraded and proper angiogenesis has occurred. On 14th day animal was also observed and found that treated one with biomaterial (polyurethane) showed excellent biocompatibility and degradation than the other groups. The tissue healing was also improved where biomaterial was used. Synthesized polyurethane has a similar kind of biocompatibility and degradation as comparable biomaterials, including commercial mesh [40]. Complete degradation revealed the biocompatibility and, significant degradation of the synthesized polyurethane membrane. The result of tissue repair was quite impressive and excellent, comparable with standard mesh used in surgery. The material was promoting angiogenesis as per the final observation.

Fig. 11.

a After 7th day the degradation of polyurethane and no infections, b After 14th day, almost complete degradation and proper angiogenesis

Histopathological test of explanted tissue was stained with H&E [41]. The examination result was shown in Fig. 12. In Group-I the no of cells was highest as no treatment took place in this Group. Similarly challenged group (Group-II) was shown the least no of cells, among others. Group-III and Group IV were shown almost equal no of fibroblast cells, and collagen content in both groups (polyurethane treated, and mesh treated) had shown almost similar in the tissue healing process.

Fig. 12.

Histopathological examination of excised tissue with H and E staining

This examination reveals that synthesize polyurethane membrane has a similar kind of cell proliferation capacity in comparison with commercially available mesh. Sufficient no of cell proliferation in the polyurethane treated group was clearly denoted the material effectiveness towards in vivo treatment. It is also observed that polyurethane synthesized (Group II) provides a better healing rate with a prominent layer of stratum corneum and granulosum than the commercial mesh (Group IV).

Conclusion

In this study, the main aim was to synthesize and characterize the ester diol based polyurethane and to check the proficiency of synthesized PU as a biomaterial for hypopharyngeal tissue engineering research. Synthesized polyurethane membrane has shown the presence of significant functional groups and adequate surface morphology. Mechanical property analysis refers to it as a soft and less brittle material. The synthesized membrane is degraded in the SBF solution due to ester linkage in the backbone of the polyurethane membrane that signifies the material as a biodegradable. PBMC proliferation over the surface of the polyurethane membrane exhibit no cytotoxicity and hemolysis percentage indicates high hemocompatibility. Antimicrobial assay ensured that the material didn’t promote bacterial growth and also inhibited the surrounding bacterial growth. Primary hypopharyngeal fibroblast culture undergoes FITC conjugated immunofluorescence staining to express the sufficient growth on the polyurethane membrane followed by a mitochondrial activity to access the cytocompatibility of the material. Antimicrobial assay ensured that the material didn’t promote bacterial growth and also inhibited the surrounding bacterial growth. Subcutaneous implantation of the polyurethane membrane in rats suggests that the material has excellent biocompatibility and sufficient biodegradation property. This fact was justified by histopathological examination that showed sufficient collagen and fibroblast cell proliferation in explanted tissue. From the overall study, it may assume that the product chemistry, biodegradation, and biocompatible property confirm the synthesized polyurethane membrane as a dynamic biomaterial might be used for hypopharyngeal tissue engineering application.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Mr. Samrat Paul, a research scholar in SBSE, Jadavpur University, for the support in PBMC isolation and hemocompatibility testing. The author would like to thank the School of Nanoscience and Technology, Jadavpur University, for providing the Scanning Electron Microscope facility. The author would like to acknowledge the Department of Metallurgical and Material Engineering, Jadavpur University, Kolkata, for giving FTIR instrumentational facility.

Funding

The authors received no financial grant for this research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Imon Chakraborty declares that he has no conflict of interest. Chowdhury Mobaswar Hossain declares that he has no conflict of interest. Piyali Basak declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Murugan R, Ramakrishna S. Design strategies of tissue engineering scaffolds with controlled fiber orientation. Tiss Eng. 2007;13(8):1845–1866. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung BG, Khademhosseini A. Special issue on tissue engineering. Biomed Eng Lett. 2013;3:115–116. doi: 10.1007/s13534-013-0107-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma PX, Zhang R. Synthetic nano scale fibrous extracellular matrix. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;46(1):60–72. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199907)46:1<60::AID-JBM7>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bil M, Ryszkowska J, Woźniak P, Kurzydłowski KJ, Lewandowska-Szumieł M. Optimization of the structure of polyurethanes for bone tissue engineering applications. Acta Biomater. 2010;6(7):2501–2510. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cherng JY, Hou TY, Shih MF, Talsma H, Hennink WE. Polyurethane-based drug delivery systems. Int J Pharm. 2013;450(1–2):145–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seal BL, Otero TC, Panitch A. Polymeric biomaterials for tissue and organ regeneration. Mater Sci Eng R Rep. 2001;34(4–5):147–230. doi: 10.1016/S0927-796X(01)00035-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duru Kamac U, Kamac M. Preparation of polyvinyl alcohol, chitosan and polyurethane-based pH-sensitive and biodegradable hydrogels for controlled drug release applications. Int J Polym Mater Po. 2019;1:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caridade SG, Merino EG, Alves NM, de Zea Bermudez V, Boccaccini AR, Mano JF. Chitosan membranes containing micro or nano-size bioactive glass particles: evolution of biomineralization followed by in situ dynamic mechanical analysis. J Mech Behav Biomed. 2013;20:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ivanoska-Dacikj A, Bogoeva-Gaceva G, Krumme A, Tarasova E, Scalera C, Stojkovski V, Gjorgoski I, Ristoski T. Biodegradable polyurethane graphene oxide scaffolds for soft tissue engineering: in vivo behavior assessment. Int J Polym Mater Po. 2019;1:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang X, Gu J, Lin L, Zhang Y. Investigation on the modification to polyurethane by multi walled carbon nanotubes. Pigm Resin Technol. 2011;40(4):240–246. doi: 10.1108/03699421111147317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lai YC, Baccei LJ. Novel polyurethane hydrogels for biomedical applications. J Appl Polym. 1991;42(12):3173–3179. doi: 10.1002/app.1991.070421210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basak P, Sen S. Degradation study and its effect in release of ciprofloxacin from polyetherurethane. Adv Mat Res. 2012;584:474–478. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim Y, Son S, Chun C, Kim JT, Lee DY, Choi HJ, Kim TH, Cha EJ. Effect of PEG addition on pore morphology and biocompatibility of PLLA scaffolds prepared by freeze drying. Biomed Eng Lett. 2016;6:287–295. doi: 10.1007/s13534-016-0241-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kylma J, Seppala JV. Synthesis and characterization of a biodegradable thermoplastic poly (ester-urethane) elastomer. Macromolecules. 1997;30(10):2876–2882. doi: 10.1021/ma961569g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawai F, Schink B. The biochemistry of degradation of polyethers. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 1987;6(3):273–307. doi: 10.3109/07388558709089384. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lowe B, Nam SY. Synthesis and biocompatibility assessment of a cysteine-based nanocomposite for applications in bone tissue engineering. Biomed Eng Lett. 2016;6:271–275. doi: 10.1007/s13534-016-0239-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tatai L, Moore TG, Adhikari R, Malherbe F, Jayasekara R, Griffiths I, Gunatillake PA. Thermoplastic biodegradable polyurethanes: the effect of chain extender structure on properties and in vitro degradation. Biomaterials. 2007;28(36):5407–5417. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmed T, Saleem A, Ramyakrishna P, Rajender B, Gulzar T, Khan A, Asiri AM. Nanostructured polymer composites for bio-applications. Micro Nano Technol. 2019;1:167–188. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mihara M, Iida T, Hara H, Hayashi Y, Yamamoto T, Mitsunaga N, Todokoro T, Uchida G, Koshima I. Reconstruction of the larynx and aryepiglottic fold using a free radial forearm tendocutaneous flap after partial laryngopharyngectomy: a case report. Microsurgery. 2012;32(1):50–54. doi: 10.1002/micr.20940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rees LE, Gunasekaran S, Sipaul F, Birchall MA, Bailey M. The isolation and characterisation of primary human laryngeal epithelial cells. Mol Immunol. 2006;43(6):725–730. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uzcudun AE, Fernández PB, Sánchez JJ, Grande AG, Retolaza IR, Barón MG, Bouzas JG. Clinical features of pharyngeal cancer: a retrospective study of 258 consecutive patients. J Laryngol Otol. 2001;115(2):112–118. doi: 10.1258/0022215011907703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan JY, Wei WI. Current management strategy of hypopharyngeal carcinoma. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2013;40(1):2–6. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cobleigh MA, Kennedy JL, Wong AC, Hill JH, Lindholm KM, Tiesenga JE, Kiang R, Applebaum EL, McGuire WP. Primary culture of squamous head and neck cancer with and without 3T3 fibroblasts and effect of clinical tumor characteristics on growth in vitro. Cancer. 1987;59(10):1732–1738. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870515)59:10<1732::AID-CNCR2820591010>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higdon LE, Lee K, Tang Q, Maltzman JS. Virtual global transplant laboratory standard operating procedures for blood collection, PBMC isolation, and storage. Transpl Direct. 2016;2(9):e101. doi: 10.1097/TXD.0000000000000613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnston N, Yan JC, Hoekzema CR, Samuels TL, Stoner GD, Blumin JH, Bock JM. Pepsin promotes proliferation of laryngeal and pharyngeal epithelial cells. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(6):1317–1325. doi: 10.1002/lary.23307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boncler M, Różalski M, Krajewska U, Podsędek A, Watala C. Comparison of PrestoBlue and MTT assays of cellular viability in the assessment of anti-proliferative effects of plant extracts on human endothelial cells. J Pharmacol Tox Met. 2014;69(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marshall NJ, Goodwin CJ, Holt SJ. A critical assessment of the use of microculture tetrazolium assays to measure cell growth and function. Growth Regul. 1995;5(2):69–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen Z, Kang C, Chen J, Ye D, Qiu S, Guo S, Zhu Y. Surface modification of polyurethane towards promoting the ex vivo cytocompatibility and in vivo biocompatibility for hypopharyngeal tissue engineering. J Biomater Appl. 2013;28(4):607–616. doi: 10.1177/0885328212468184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hou Z, Zhang H, Qu W, Xu Z, Han Z. Biomedical segmented polyurethanes based on polyethylene glycol, poly (ε-caprolactone-co-d, l-lactide), and diurethane diisocyanates with uniform hard segment: synthesis and properties. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Po. 2016;65(18):947–956. doi: 10.1080/00914037.2016.1180612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Das S. Pervaporation separation of organic compound-water mixtures by polymer membranes (Doctoral dissertation, IIT, Kharagpur). 2006.

- 31.Jiang F, Robin AM, Katakowski M, Tong L, Espiritu M, Singh G, Chopp M. Photodynamic therapy with photofrin in combination with Buthionine Sulfoximine (BSO) of human glioma in the nude rat. Lasers Med Sci. 2003;18(3):128–133. doi: 10.1007/s10103-003-0269-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guan J, Sacks MS, Beckman EJ, Wagner WR. Synthesis, characterization, and cytocompatibility of elastomeric, biodegradable poly (ester urethane) ureas based on poly (caprolactone) and putrescine. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;61(3):493–503. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma Z, Mao Z, Gao C. Surface modification and property analysis of biomedical polymers used for tissue engineering. Colloids Surf B. 2007;60(2):137–157. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hollister SJ. Porous scaffold design for tissue engineering. Nat Mater. 2005;4(7):518–524. doi: 10.1038/nmat1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jia Q, Xia Y, Yin S, Hou Z, Wu R. Influence of well-defined hard segment length on the properties of medical segmented polyesterurethanes based on poly (ε-caprolactone-co-l-lactide) and aliphatic urethane diisocyanates. Int J Polym Mater Po. 2017;66(8):388–397. doi: 10.1080/00914037.2016.1233416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y, Ouyang H, Lim CT, Ramakrishna S, Huang ZM. Electrospinning of gelatin fibers and gelatin PCL composite fibrous scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res. 2005;72(1):156–165. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haaparanta AM, Jarvinen E, Cengiz IF, Ella V, Kokkonen HT, Kiviranta I, Kellomaki M. Preparation and characterization of collagen/PLA, chitosan PLA, and collagen chitosan PLA hybrid scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2014;25(4):1129–1136. doi: 10.1007/s10856-013-5129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Everett W, Scurr DJ, Rammou A, Darbyshire A, Hamilton G, De Mel A. A material conferring hemocompatibility. Sci. Rep. 2016;6(1):1–2. doi: 10.1038/srep26848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strutz F, Okada H, Lo CW, Danoff T, Carone RL, Tomaszewski JE, Neilson EG. Identification and characterization of a fibroblast marker: FSP1. Int J Cell Biol. 1995;130(2):393–405. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.2.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cobb WS, Kercher KW, Heniford BT. The argument for lightweight polypropylene mesh in hernia repair. Surg Innov. 2005;12(1):63–69. doi: 10.1177/155335060501200109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sravya T, Rao GV, Kumari MG, Sagar YV, Sivaranjani Y, Sudheerkanth K. Evaluation of biosafe alternatives as xylene substitutes in hematoxylin and eosin staining procedure: a comparative pilot study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol. 2018;22(1):148. doi: 10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_172_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]