Abstract

In this paper, we aim to provide professional guidance to clinicians who are managing patients with chronic liver disease during the current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Singapore. We reviewed and summarised the available relevant published data on liver disease in COVID-19 and the advisory statements that were issued by major professional bodies, such as the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and European Association for the Study of the Liver, contextualising the recommendations to our local situation.

Keywords: COVID-19, hepatology, SARS-CoV-2

INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), a disease caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus, has become a global pandemic. The unique issues in managing patients with liver disease need to be addressed. Abnormalities in liver function may be encountered in patients with COVID-19. Patients with chronic liver disease may potentially be at a higher risk of adverse outcomes, either due to reduced access to healthcare or their immunocompromised status. Hence, the Board of the Chapter of Gastroenterologists, Academy of Medicine, Singapore, initiated the formation of a workgroup to review and summarise the currently available data on liver disease in COVID-19, and to formulate recommendations to guide management. This report represents the collective opinion of the authors and is endorsed by the Board of the Chapter of Gastroenterologists, College of Physicians, Singapore.

The available published scientific data and the advisory statements of major professional bodies (American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases [AASLD] and European Association for the Study of the Liver [EASL]) were reviewed.(1,2) Relevant information was summarised and contextualised to our local situation, especially in areas of controversies and areas that were not addressed. The practice of evidence-based medicine requires objective scientific data, but where such data is lacking, decisions must be made based on the limited available evidence that is extrapolated from indirect data, or based on expert opinion. We aimed to provide professional guidance to clinicians who are managing patients with liver disease in Singapore during the COVID-19 pandemic.

LIVER DISEASE CAUSED BY COVID-19

Current understanding

SARS-CoV-2 binds to target cells through the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, which occurs abundantly on liver and biliary epithelial cells.(3) Therefore, the liver is a potential target for infection.

Potential causes of liver injury include systemic inflammatory response, ischaemia/hypotension, myositis, direct cytopathic effect or drug-induced liver injury. However, differentiating these causes may be difficult.(1)

Liver function abnormalities, predominantly raised aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and bilirubin, occurred in 14%–53% of hospitalised patients with COVID-19.(4-9)

Elevated ALT and AST are usually 1–2 times the upper limit of normal, with rare cases of severe acute hepatitis.(4-9)

Liver injury is usually mild and does not require specific treatment or prolong hospitalisation.(9)

Liver injury is more common among severe COVID-19 cases. Low serum albumin on admission is a marker of severe COVID-19.(4,5)

Liver injury occurs in 58%–78% of death cases from COVID-19.(10-13) However, death from liver failure has not been specifically reported in patients with COVID-19.(4)

Liver biopsy findings in COVID-19 patients are nonspecific and vary from moderate microvesicular steatosis with mild mixed lobular and portal activity to focal necrosis.(14,15)

Therapeutic agents that are used to manage COVID-19 may be hepatotoxic, and these include remdesivir, tocilizumab and, less commonly, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin.(1)

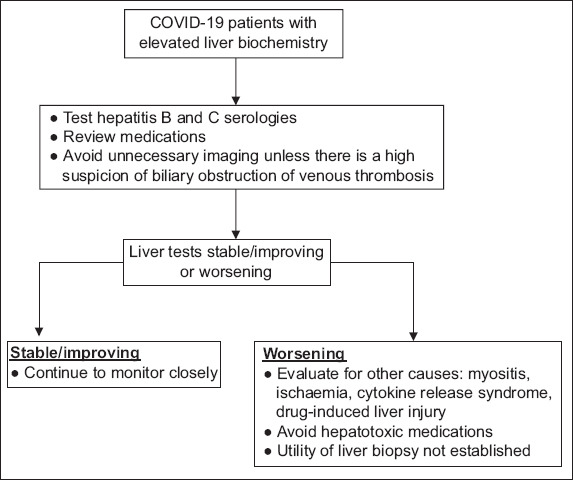

An approach to evaluating a patient with COVID-19 and elevated liver biochemistries has been suggested by the AASLD (Fig. 1).(1)

Fig. 1.

Chart shows the approach to the patient with COVID-19 and elevated serum liver biochemistries. [Adapted from Clinical insights for Hepatology and liver transplant providers during COVID-19 pandemic, AASLD.(1)]

Recommendations

When assessing patients with COVID-19 and elevated liver biochemistries, consider aetiologies that are unrelated to COVID-19 (e.g. hepatitis B and C), as well as other causes of elevated biochemistries (e.g. myositis, ischaemia and cytokine release syndrome).(1)

To limit unnecessary transportation of patients with COVID-19, liver imaging should be avoided unless there is clinical suspicion for biliary obstruction or venous thrombosis.(1)

The presence of abnormal liver biochemistries should not be a contraindication to use of investigational or off-label therapeutic agents for the treatment of COVID-19.(1)

MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITH PRE-EXISTING LIVER DISEASE IN THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

Current understanding

Patients with chronic liver disease/hepatocellular carcinoma/cirrhosis

Information on the impact of COVID-19 in patients with chronic liver disease is limited.(1)

There is no evidence that patients with stable chronic liver disease (e.g. due to chronic hepatitis B or C, primary biliary cirrhosis or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [NAFLD]) have increased susceptibility to COVID-19.(1)

General preventive measures, including hand hygiene and physical distancing, have been shown to be effective in reducing the incidence of COVID-19 in patients with decompensated cirrhosis.(16)

Patients with chronic liver disease should receive pneumococcal and influenza vaccination regardless of age.(17,18) The World Health Organization has advised that pneumococcal and influenza vaccination should be prioritised for vulnerable population groups during the COVID-19 pandemic.(19)

Patients with cancer have a higher risk of COVID-19 and poorer outcomes.(20) However, it remains unknown whether patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) have increased risk for severe COVID-19.

In liver transplant recipients or patients with autoimmune hepatitis who are on immunosuppressive therapy, acute cellular rejection or disease flare should not be presumed in the face of an active COVID-19 pandemic.(1)

Patients with decompensated cirrhosis and liver transplantation

There is limited data on the impact of COVID-19 among patients with decompensated cirrhosis or those awaiting liver transplantation.(1)

Donor screening for COVID-19 is recommended for most organ procurement organisations.(21) Those who test positive are ineligible for organ donation.(1)

Transplantation in COVID-19 positive recipients is currently not recommended.(1)

Recommendations

Vaccination

Consider influenza and pneumococcal vaccination for patients with chronic liver disease or cirrhosis, where feasible.(2)

Outpatient clinic visit

Efforts should be made to limit outpatient visits to patients who need to be seen in person.(1) Where possible, consider the use of phone consultations or telemedicine to replace in-person clinic visits.(2)

If patients need to be seen in person, ensure that all patients are screened for symptoms of COVID-19 or potential exposure, as per the recommendations of the Ministry of Health, Singapore (MOH).

Consider limiting the number of caregivers accompanying patients to the clinic visit.(1)

Ensure appropriate distancing in the waiting area.(1)

A face mask is mandatory for physicians in the outpatient clinic.(22)

Patients with COVID-19 symptoms should not be evaluated in the outpatient clinic. They should be evaluated in a dedicated facility equipped with proper personal protective equipment and relevant infection control protocols.(1) Non-urgent consultations should be deferred until post-recovery.

Chronic hepatitis B and C

Consider using telemedicine for follow-up visits of stable patients on long-term antiviral therapy, and send follow-up prescriptions by mail or through home medication services.(2)

Continue treatment for chronic hepatitis B and C patients who are already on treatment.(1)

Consider delaying the initiation of treatment for chronic hepatitis C patients without decompensated cirrhosis, as starting treatment would require a follow-up visit to monitor for adverse effect within four weeks.(1)

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Patients with NAFLD or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis may suffer from concomitant metabolic comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension and obesity, which place them at increased risk of severe COVID-19. The management of these comorbidities should be optimised.(2)

Autoimmune liver disease

Patients with autoimmune liver disease who are in remission and on a stable dose of immunosuppressive therapy should not have their immunosuppression reduced, unless there are specific indications to do so (e.g. medication-induced lymphopenia or bacterial/fungal superinfection in severe COVID-19). The decision to reduce immunosuppression should be done in consultation with the relevant specialist.(2)

Liver cirrhosis

Consider telemedicine consultations in place of in-person visits, if feasible.(2)

Patients should receive vaccination for Streptococcus pneumoniae and influenza, where feasible. (2)

Regular surveillance for HCC should be continued. A delay in imaging for HCC surveillance may be considered depending on the individual patient’s risk profile.(1)

Endoscopy for variceal screening should be reserved for patients at high risk of variceal bleeding, such as those with a history of variceal bleeding or signs of significant portal hypertension.(2) Non-invasive risk assessment tools (e.g. Baveno-VI criteria) should be used to risk-stratify compensated cirrhosis patients for variceal screening.(23,24)

Patients undergoing secondary prophylaxis that aims for complete endoscopic variceal obliteration should continue the scheduled endoscopy in order to prevent interval severe variceal bleeding, unless these patients are diagnosed to have or suspected to have COVID-19 or had close exposure to COVID-19, in which case the procedure should be postponed.

Consider optimising outpatient ambulatory services for paracentesis to prevent re-admission in cirrhosis with refractory ascites.(2)

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Continue the usual surveillance for HCC. Based on patient and facility circumstances, an arbitrary delay of two months is reasonable. The risks and benefits of delaying surveillance should be discussed with the patient and documented.(1)

Proceed with HCC treatment as indicated. It is not advisable to delay treatment due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as the duration of the pandemic is unknown.(1)

Patients on immunosuppression

In immunosuppressed liver disease patients without COVID-19, do not make anticipatory adjustments to current immunosuppressive drugs or dosages.(1)

-

In immunosuppressed liver disease patients with COVID-19:(1)

- Prednisolone: consider minimising the dose of high-dose prednisolone but maintaining a sufficient dosage to avoid adrenal insufficiency.

- Azathioprine or mycophenolate: consider reducing the dose in patients with active COVID-19, especially if there is lymphopenia, fever or worsening pneumonia.

- Calcineurin inhibitors (CNI): consider reducing but not stopping daily CNI dose, especially in the setting of lymphopenia, fever or worsening pneumonia in patients with active COVID-19.

Initiate immunosuppressive therapy in patients with or without COVID-19, if there are strong indications for treatment (e.g. autoimmune hepatitis, graft rejection).(1)

In patients with COVID-19, be cautious when initiating prednisolone or other immunosuppressive therapy, if the risk may outweigh the potential benefit (e.g. in alcohol-associated hepatitis).(1)

Endoscopy

SARS-CoV-2 can potentially be present in saliva. Faecal-oral SARS-CoV-2 transmission has been reported.(25,26)

As endoscopy is an aerosol-generating procedure, the Joint Gastrointestinal Societies (the American Gastroenterological Association, the AASLD, the American College of Gastroenterology and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy) recommend deferring non-urgent/elective endoscopy procedures such as variceal screening.(27-29)

Elective endoscopy should proceed only if the endoscopy is likely to have a significant impact on the patient’s care, according to clinical practice guidelines.

Please refer to the professional guidance on gastrointestinal endoscopy during the COVID-19 pandemic published by the Singapore Chapter of Gastroenterologists.(28)

Liver biopsy

-

In patients without COVID-19, the decision to proceed with liver biopsy depends on the local burden of COVID-19 and the individual indication for histological assessment.(2)

- Liver biopsy should be performed in patients with liver disease of unknown aetiology (e.g. where delay in diagnosis and appropriate treatment can lead to poor outcome) or to confirm the diagnosis before initiating treatment (e.g. to confirm the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis before starting corticosteroids).

- Liver biopsy may be deferred for grading/staging of patients with NAFLD or chronic viral hepatitis, or in patients with only mildly elevated transaminases (e.g. ALT < 3 × upper limit of normal) of unknown aetiology.

In patients with COVID-19, liver biopsy should be deferred in most patients, as the treatment of COVID-19 outweighs the diagnosis of co-existing liver disease.(2)

Pharmacotherapy

In patients with pre-existing chronic liver disease who develop COVID-19, there is concern of drug interactions with potential therapeutic agents for COVID-19. A recent position paper by EASL-European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases provides a detailed review of considerations for drug interactions in patients with chronic liver disease or post-liver transplantation.(2)

-

Consult the pharmacist and/or hepatologist for potential drug-induced liver injury in COVID-19 patients, if uncertain.

- Paracetamol: Avoid doses > 2 g per day in patients with underlying chronic liver disease.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Whether NSAIDs worsen COVID-19 remains inconclusive. NSAIDs should be used with caution due to potential drug-induced liver injury, and should be avoided in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension due to increased risk of hepatorenal syndrome.(30-32)

Liver transplant

The advisory from MOH on transplant activities should be adhered to.

For further details on management of liver transplant patients, the AASLD Clinical Insights for Hepatology and Liver Transplant Providers During the COVID-19 Pandemic advisory provides excellent recommendations that are largely applicable to our local context.(1)

Multidisciplinary team meetings

Existing multidisciplinary teams (e.g. liver transplantation or HCC) should continue during the period of the pandemic via teleconferencing (if resources are available) to maintain physical distancing while addressing the diagnostic and management plans for patients with liver disease. (1)

CONCLUSION

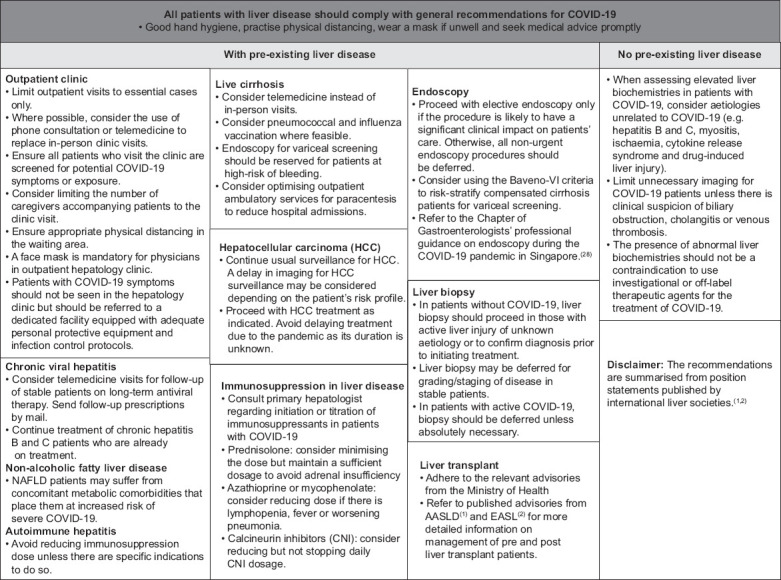

The current management strategies for COVID-19 focus on public health and infection control measures to contain the disease, and respiratory support and treatment of severe cases. There are implications for patients with underlying gastroenterological and liver diseases, and clinicians who are involved in their care should be cognisant of these issues.(33) The current recommendations address practical issues of how to approach a patient with COVID-19 infection presenting with abnormalities of liver function, and provide guidance for the management of patients with pre-existing chronic liver disease. A summary of the recommendations is shown in Fig. 2. They are based on the data and evidence available up to the time of publication, as well as expert opinion where such data is lacking. This document has not undergone the methodical rigour of a practice guideline and does not define a standard of care. It is not intended to be a substitute for the independent professional judgement of the healthcare provider.

Fig. 2.

Summary of recommendations published by international liver societies(1,2) and contextualised for Singapore.(28)

REFERENCES

- 1.American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. AASLD clinical insights for hepatology and liver transplant providers during the COVID-19 pandemic [online] [Accessed April 8, 2020]. Available at: https://www.aasld.org/sites/default/files/2020-04/AASLD-COVID19-ClinicalInsights-4.07.2020-Final.pdf .

- 2.Boettler T, Newsome PN, Mondelli MU, et al. Care of patients with liver disease during the COVID-19 pandemic:EASL-ESCMID Position Paper. JHEP Rep. 2020;2:100113. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2020.100113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lan J, Ge J, Yu J, et al. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020;581:215–20. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu L, Liu J, Lu M, Yang D, Zheng X. Liver injury during highly pathogenic human coronavirus infections. Liver Int. 2020;40:998–1004. doi: 10.1111/liv.14435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China:a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang C, Shi L, Wang FS. Liver injury in COVID-19:management and challenges. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:428–30. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30057-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan Z, Chen L, Li J, et al. Clinical features of COVID-19-related liver functional abnormality. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:1561–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang B, Zhou X, Qiu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of 82 death cases with COVID-19. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0235458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang Y, Yang R, Xu Y, Gong P. Clinical characteristics of 36 non-survivors with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. In:medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.27.20029009. [Preprint] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China:summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Epidemiology Working Group for NCIP Epidemic Response, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention [The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China] Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:145–51. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.02.003. Chinese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:420–2. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yao XH, Li TY, He ZC, et al. [A pathological report of three COVID-19 cases by minimally invasive autopsies] Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2020;49:411–7. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112151-20200312-00193. Chinese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiao Y, Pan H, She Q, Wang F, Chen M. Prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:528–9. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30080-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alter MJ. Vaccinating patients with chronic liver disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2012;8:120–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Liver diseases and adult vaccination. [Accessed April 10, 2020]. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/adults/rec-vac/health-conditions/liver-disease.html .

- 19.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Guidance on routine immunization services during COVID-19 pandemic in the WHO European Region (2020) [Accessed April 10, 2020]. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/hepatitis/publications/2020/guidance-on-routine-immunization-services-during-covid-19-pandemic-in-the-who-european-region-2020 .

- 20.Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection:a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335–7. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Transplantation Society. Guidance on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) for transplant clinicians. [Accessed April 10, 2020]. Available at: https://tts.org/tid-about/tid-presidents-message/23-tid/tid-news/657-tid-update-and-guidance-on-2019-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-for-transplant-id-clinicians .

- 22.Ng K, Poon BH, Kiat Puar TH, et al. COVID-19 and the risk to health care workers:a case report. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:766–7. doi: 10.7326/L20-0175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stafylidou M, Paschos P, Katsoula A, et al. Performance of Baveno VI and expanded Baveno VI criteria for excluding high-risk varices in patients with chronic liver disease:a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1744–55.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Franchis R. Baveno VI Faculty et al. Expanding consensus in portal hypertension. Report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop:stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2015;63:743–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gu J, Han B, Wang J. COVID-19:gastrointestinal manifestations and potential fecal-oral transmission. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1518–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao F, Tang M, Zheng X, et al. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1831–3.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Joint GI Society Message:COVID-19 clinical insights for our community for gastroenterologists and gastroenterology care providers. [Accessed April 10, 2020]. Available at: https://www.asge.org/home/joint-gi-society-message-covid-19 .

- 28.Ang TL, Li JW, Vu CKF, et al. Chapter of Gastroenterologists professional guidance on risk mitigation for gastrointestinal endoscopy during COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 2020;61:345–9. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2020050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. ESGE and ESGENA position statement on gastrointestinal endoscopy and COVID-19 pandemic. [Accessed April 10, 2020]. Available at: https://www.esge.com/esge-and-esgena-position-statement-on-gastrointestinal-endoscopy-and-the-covid-19-pandemic/

- 30.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA advises patients on use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for COVID-19. [Accessed April 10, 2020]. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-advises-patients-use-non-steroidal-anti-inflammatory-drugs-nsaids-covid-19 .

- 31.Ministry of Health, Singapore. Should ibuprofen be used for COVID-19? [Accessed April 10, 2020]. Available at: https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider5/clinical-evidence-summaries/ibuprofen-in-covid-19-(21-march-2020).pdf .

- 32.Sriuttha P, Sirichanchuen B, Permsuwan U. Hepatotoxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs:a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Hepatol. 2018;2018:5253623. doi: 10.1155/2018/5253623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tay SW, Teh KKJ, Wang LM, Ang TL. Impact of COVID 19:perspectives from gastroenterology. Singapore Med J. 2020;61:460–2. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2020051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]