Abstract

Recent events, most notably the Global Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, have made it increasingly apparent that liquidity is synonymous with corporate survival. In this paper, we explore how governments can fulfill an important need as suppliers of liquidity. Building on the financing advantage view of state ownership, we theorize how state-owned enterprises (SOEs) may provide capital by offering trade credit to customer firms. The data indicate a positive relation between the level of state ownership and the provision of trade credit. Using an institution-focused framework, we further determine that the nation’s institutional environment systematically affects the opportunities and motivations for SOEs to grant trade credit. Specifically, we find that SOEs grant more trade credit in countries with less developed financial markets, weaker legal protection of creditors, less comprehensive information-sharing mechanisms, more collectivist societies, left-wing governments, and higher levels of unemployment. Firm-level factors also influence the credit-granting decisions of SOEs, with SOEs with lower levels of state ownership and higher extents of internationalization offering lower amounts of trade credit. Overall, our study offers novel insights regarding the important role of state-owned firms as providers of liquidity.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1057/s41267-021-00406-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: privatization, state ownership, trade credit, formal institutions, informal institutions, financial market development

Resume

Les événements récents, notamment la crise financière mondiale et la pandémie de COVID-19, ont montré de plus en plus que la liquidité est synonyme de survie des entreprises. Dans cet article, nous explorons comment les gouvernements peuvent répondre à un besoin important en tant que fournisseurs de liquidités. En nous appuyant sur la perspective de l’avantage financier de la propriété de l’État, nous théorisons comment les entreprises publiques (EP) peuvent fournir des capitaux en offrant des crédits commerciaux aux entreprises clientes. Les données indiquent une relation positive entre le niveau de propriété de l’État et l’offre de crédits commerciaux. En utilisant un cadre axé sur les institutions, nous déterminons en outre que l’environnement institutionnel du pays affecte systématiquement les possibilités et les motivations des EP d’octroyer des crédits commerciaux. Plus précisément, nous constatons que les EP accordent plus de crédits commerciaux dans les pays avec des marchés financiers moins développés, une protection juridique plus faible des créanciers, des mécanismes d’échanges d’informations moins complets, des sociétés plus collectivistes, des gouvernements de gauche et des taux de chômage plus élevés. Des facteurs au niveau de l’entreprise influencent également les décisions d’octroi de crédit des EP, les EP avec des niveaux inférieurs de propriété de l’État et des niveaux plus élevés d’internationalisation offrant des montants de crédits commerciaux plus faibles. Dans l’ensemble, notre étude offre de nouvelles perspectives sur le rôle important des entreprises publiques en tant que fournisseurs de liquidités.

Resumen

Los sucesos recientes, en particular la crisis financiera mundial y la pandemia COVID-19, han hecho cada vez más evidente que la liquidez es sinónimo de supervivencia corporativa. En este documento, exploramos cómo los gobiernos pueden satisfacer una necesidad importante como proveedores de liquidez. Basándonos en la visión de la ventaja financiera de la propiedad estatal, teorizamos cómo las empresas de propiedad estatal (SOEs por sus iniciales inglés) pueden proporcionar capital ofreciendo crédito comercial a las empresas clientes. Los datos indican una relación positiva entre el nivel de propiedad estatal y la provisión de crédito comercial. Usando un marco centrado en las instituciones, determinamos además que el entorno institucional de la nación afecta sistemáticamente las oportunidades y motivaciones para que las empresas de propiedad estatal otorguen crédito comercial. Específicamente, encontramos que las empresas de propiedad estatal de comercio otorgan más crédito comercial en países con mercados financieros menos desarrollados, una protección jurídica más débil de los acreedores, mecanismos de intercambio de información menos amplios, sociedades más colectivistas, gobiernos de izquierda y mayores niveles de desempleo. Los factores a nivel de las empresas también influyen en las decisiones de concesión de crédito de las empresas de propiedad estatal, con empresas de propiedad estatal con niveles más bajos de propiedad estatal y mayores extensiones de internacionalización que ofrecen menores cantidades de crédito comercial. En general, nuestro estudio ofrece aportes novedosos sobre el importante papel de las empresas de propiedad estatal como proveedores de liquidez.

Resumo

Eventos recentes, mais notadamente a Crise Financeira Global e a pandemia COVID-19, tornaram cada vez mais evidente que liquidez é sinônimo de sobrevivência corporativa. Neste artigo, exploramos como governos podem atender a uma importante necessidade como fornecedores de liquidez. Com base na visão da vantagem de financiamento de propriedade estatal, teorizamos como empresas estatais (SOEs) podem fornecer capital ao oferecer crédito comercial a empresas clientes. Os dados indicam uma relação positiva entre o nível de propriedade do Estado e a oferta de crédito comercial. Usando um modelo focado em instituições, determinamos ainda que o ambiente institucional do país afeta sistematicamente as oportunidades e motivações para SOEs concederem crédito comercial. Especificamente, descobrimos que SOEs concedem mais crédito comercial em países com mercados financeiros menos desenvolvidos, proteção legal mais fraca a credores, mecanismos de compartilhamento de informações menos abrangentes, sociedades mais coletivistas, governos de esquerda e níveis mais elevados de desemprego. Fatores no nível da firma também influenciam as decisões de concessão de crédito de SOEs, sendo que SOEs com níveis mais baixos de propriedade estatal e mais altos de internacionalização oferecem menores quantidades de crédito comercial. De modo geral, nosso estudo oferece novos insights sobre o importante papel de empresas estatais como provedoras de liquidez.

Abstract

近年的事件, 尤其是全球金融危机和新冠病毒(COVID-19)大流行, 越来越明显地使流动性成为企业生存的代名词。在本文中, 我们探索了政府作为流动性的提供者如何满足重要需求。基于国家所有制融资优势的观点, 我们对国有企业(SOE)如何通过向客户公司发放贸易信贷来提供资本进行了理论化。数据表明国家所有权水平与贸易信贷发放之间存在正相关关系。使用制度距焦的框架, 我们进一步确定, 国家的制度环境系统地影响了SOE发放贸易信贷的机会和动机。具体而言, 我们发现, SOE在金融市场欠发达、债权人的法律保护薄弱、信息共享机制欠缺, 较多集体主义的社会, 左翼政府和失业率较高的国家中发放较多的贸易信贷。公司层面的因素也影响SOE的授信决策, 国家所有权水平较低的和国际化程度较高的SOE所发放的贸易信贷额较低。总体而言, 我们的研究对国有企业作为流动性的提供者的重要作用提出了新颖的见解。

INTRODUCTION

Understanding how state ownership influences firm decision-making and performance has been an important theme in international business research and at JIBS (e.g., Boubakri, Guedhami, Kwok, & Saffar, 2016; Cuervo-Cazurra, Inkpen, Musacchio, & Ramaswamy, 2014; Vaaler & Schrage, 2009). The argument for state ownership rests on the ability of government ownership to overcome market weaknesses and allow firms to pursue socially desirable objectives (Megginson & Netter, 2001). This paper investigates one of the ways state-owned enterprises (SOEs) can compensate for financial market weakness, namely, by supplying trade credit.

Trade credit is pervasive around the world (Beck, Demirgüc-Kunt, & Maksimovic, 2008; Demirgüc-Kunt & Maksimovic, 2001; El Ghoul & Zheng, 2016; Rajan & Zingales, 1995). For instance, in our sample of publicly listed industrial firms from 64 countries, aggregate trade credit reached nearly $US 4.7 trillion in 2013, with approximately 20% (16%) of the average firm’s sales (assets) in trade receivables. Speaking broadly to the importance of this ubiquitous source of financing, extant research (e.g., Carbo-Valverde, Rodriguez-Fernandez, & Udell, 2016; Fisman & Love, 2003; Garcia-Appendini & Montoriol-Garriga, 2013) concludes that industries that rely on trade credit experience faster growth and exhibit greater resiliency to financial crises. However, compared to other sources of financing, prior literature tells us little about the determinants of the provision of trade credit in an international setting.

Building on the financing advantage theory of trade credit (e.g., Meltzer, 1960; Nilsen, 2002; Petersen & Rajan, 1997), we posit that the link between state ownership and trade credit is contingent upon SOEs’ greater access to financing. The soft budget constraint view holds that the government can relax an SOE’s budget constraint by providing easy access to finance, as well as tax discounts and other forms of support (Kornai, Maskin, & Roland, 2003). We argue that these financing advantages present the SOE with greater opportunities to extend trade credit, opportunities that will be further enhanced by higher levels of state ownership. Thus, the financing advantage theory predicts that firms with greater levels of state ownership should provide more trade credit.

Consistent with the financing advantage theory, the data indeed indicate a strongly significant positive relation between state ownership and trade credit. However, our data also indicate that the relation between state ownership and trade credit varies across countries (i.e., there appears to be variation in this relation that the financing advantage theory alone cannot fully explain). Thus, the unanswered (and perhaps more intriguing) question is why the relation between state ownership and trade credit varies across nations. We turn to international business theories to seek answers. We follow Grøgaard, Rygh, and Benito (2019), Knutsen, Rygh, and Hveem (2011), and Puck and Filatotchev (2018) and similarly conduct research to “bridge” the domains of finance and international business (IB). Specifically, we endeavor to complement our more finance-centric study of trade credit provision by SOEs by positioning it within a broader IB context. To this end, we evaluate SOEs’ credit-granting decisions using core IB perspectives (Puck & Filatotchev, 2018: 2), and consider how (1) macro- or country-level, and (2) micro- or firm-level factors affect the relation between state ownership and trade credit provision.

Using an institution-focused framework (Williamson, 2000), we contend that the extent to which an SOE will exploit financing advantages is shaped by a nation’s institutional environment. Most notably, we contend that the institutional environment affects the SOE’s opportunities and motivations to extend trade credit. Accordingly, a large part of our theoretical framework and empirical analysis involves exploring the impact of various country-level (institutional) boundary conditions on credit-granting decisions by SOEs.1

Further helping us to seek answers to our question about the decision-making process of SOEs, the IB frameworks of Grøgaard et al. (2019), Knutsen et al. (2011), and Puck and Filatotchev (2018) suggest that we should consider firm-level factors (in addition to the institutional environment). Therefore, we also examine firm-level characteristics to identify clues about the relation between state ownership and trade credit. We specifically investigate how firm-level boundary conditions (such as the firm’s extent of state ownership and degree of internationalization) can impact the credit-granting decisions of SOEs.

Our sample of 574 newly privatized firms (NPFs) from 64 institutionally diverse countries provides a powerful setting for addressing these issues. We focus on NPFs because the change in ownership structure during privatization leads to changes in agency problems, information asymmetry, and implicit government guarantees. Following Chen, El Ghoul, Guedhami, and Nash (2018), we define an NPF as an entity in which state ownership has been recently reduced through privatization. An NPF will thus have a zero or positive level of residual state ownership.

The findings support our predictions of how state ownership affects trade credit and provide direct evidence of the important role of country- and firm-level boundary conditions in influencing this relation. We find robust evidence that state ownership is positively and significantly related to the supply of trade credit. Our findings further suggest that institutional characteristics, by affecting the SOE’s opportunities and motivations to extend trade credit, also can affect the relation between state ownership and trade credit provision. We identify financial, legal, informational, political, cultural, and social factors that impact the credit-granting decisions of SOEs. Furthermore, the data indicate that firm- or micro-level factors also weigh significantly on SOEs’ credit-granting decisions. Specifically, our analysis shows that the extent of state shareholdings and degree of internationalization impact the credit-granting decisions of SOEs.

Finally, we explore whether the more liberal granting of trade credit by SOEs has economic costs. The idea is that trade credit provision by SOEs may impose costs by “propping up” politically connected but inefficient firms, hence reducing efficiency-enhancing resource reallocation. Accordingly, our final empirical analysis examines the potential “dark side” of SOE-mandated trade credit by analyzing the market valuation consequences for SOEs. We find that the market tends to discount the value of trade credit provided by SOEs. This indicates that the more extensive granting of trade credit by SOEs is likely to be a loss-making subsidization, rather than a positive-NPV business decision.

Our paper adds to several strands of literature. Our paper extends the state ownership literature by identifying that trade credit from SOEs can help firms overcome limited access to capital in less developed financial markets and by documenting that governments use credit-granting by SOEs to achieve political and social objectives. Our study contributes to the growing research in international business regarding the firm-level implications of state capitalism (e.g., Boubakri et al., 2016; Grøgaard et al., 2019; Inoue, Lazzarini, & Musacchio, 2013; Lazzarini & Musacchio, 2018). Also, our cross-country dataset allows us to directly examine how differences in institutional factors may affect the formulation of the SOE’s credit-granting decisions (which helps us to understand why all state owners are not the same).

Our study’s contribution to institutional theory can primarily be positioned within the institutional economics school of thought. A pioneer of institutional economics, North (1990) recognizes that cross-country variance in institutions contributes to cross-country variance in the behavioral and organizational responses of global firms. Based upon theory from institutional economics, our study considers such institutional heterogeneity by examining the effect of differences in the quality and effectiveness of national institutions on the trade credit decisions of SOEs.

Following Inoue et al. (2013) and Musacchio et al. (2015), we recognize that weaknesses in the quality and effectiveness of institutions cause “institutional voids” that may adversely impact firm-level decision-making.2 Our study primarily considers the “institutional void” that arises due to lesser-developed capital markets. Aspects of this “institutional void” have been studied in the international business literature. For example, Oxelheim, Randoy, and Stonehill (2001) compile a list of actions that firms lacking access to well-developed capital markets may take to increase the availability of the financing required to engage in FDI.3 Our study, by identifying the liquidity-enhancing role of trade credit offered by SOEs, adds to that list of actions that can help firms overcome the “institutional void” of less-developed capital markets.

Overall, developing a better understanding of the role of SOEs as providers of liquidity contributes to a better understanding of the national context in which firms operate. Our study draws from the finance literature to add to the richness of our understanding of national context. Specifically, our paper identifies how a corporate finance decision (i.e., the granting of trade credit by SOEs) helps to improve the functioning of national capital markets by enhancing the availability of funding for liquidity-deprived firms.

STATE OWNERSHIP, COUNTRY- AND FIRM-LEVEL BOUNDARY CONDITIONS, AND TRADE CREDIT

State Ownership and Trade Credit

The corporate finance literature outlines five categories of theories that potentially explain the provision of trade credit by suppliers: (1) financing advantage, (2) price discrimination, (3) monitoring/credit enforcement, (4) implicit warranty, and (5) transaction cost. We argue that financing advantage is most relevant when considering the relation between state ownership and trade credit because it provides direct predictions of how ownership structure (i.e., state vs. private) should affect the provision of trade credit.

The financing advantage theory contends that firms with greater access to financing should be better able to provide funding to customers through trade credit. Meltzer (1960), Nilsen (2002), and Petersen and Rajan (1997) note that firms with greater ability to acquire capital will be more likely to channel the cash received to less-liquid firms by offering more trade credit. The other theories do not lend themselves as well to the evaluation of the differences between SOEs and privately owned enterprises (POEs). These other theories are also heavily predicated on the assumption that firms seek to maximize profits.4

We argue that state ownership may create an advantage with respect to access to finance because SOEs benefit from implicit government guarantees, tax discounts, preferential access to credit, and other forms of soft budget constraints, particularly during times of financial distress (Borisova, Fotak, Holland, & Megginson, 2015; Borisova & Megginson, 2011; Boubakri, El Ghoul, Guedhami, & Megginson, 2018; Faccio, Masulis, & McConnell, 2006; Holland, 2019; Kornai et al., 2003; Nash, 2017; Boubakri, Chen, El Ghoul, Guedhami, & Nash, 2020). It follows that, as the level of state ownership increases, SOEs should suffer less from financial constraints and should have greater access to finance (Holland, 2019). More importantly, the financing advantage theory suggests that SOEs can pass their access to liquidity on to their buyers through the provision of trade credit.

Our basic premise is that SOEs choose to grant more trade credit than POEs. This choice requires both opportunity and motive. While we have noted that the financial advantages from the soft budget constraint should provide the opportunity, we next consider what, specifically, drives the motivation. We identify the following characteristics (reflecting differences between SOEs and POEs) that may answer this question.

Different goals

When evaluating the motives of SOEs and POEs, Vernon (1979) observes that SOEs’ goals typically extend beyond profit maximization, and usually consider the entity’s impact on the nation’s wellbeing. More specifically, Grøgaard et al. (2019) highlight SOEs’ non-economic goals (i.e., the explicit targeting of social, allocational, and/or political aspirations). For example, Redding (2005), John, Litov, and Yeung (2008), and Bai, Lu, and Tao (2006) document that SOEs are frequently tasked with promoting societal stability by maintaining long-term employment.

Putniņš (2015) argues that the pursuit of non-economic goals (such as full employment), while inconsistent with profit maximization, aligns with the view that state ownership is justifiable in the event of market failures. Identifying key market failures as resulting from monopolies, externalities, and public goods, Putniņš (2015) contends that full employment can be considered a public good (by contributing to social stability), and that it also generates positive externalities (by deterring crime and facilitating overall wellbeing). Therefore, if an SOE’s objective is to foster full employment, it would be correspondingly motivated to maintain (if not maximize) output by granting larger amounts of trade credit.

Different risk profiles

The granting of trade credit, like the offering of any loan, involves risk to the creditor. Relative to POEs, SOEs may grant differing levels of credit because they face differing levels of risk. Vernon (1979) notes that governments are usually willing to accept greater amounts of risk than private enterprises. Arrow and Lind (1970), Benito, Rygh, and Lunnan (2016), Filatotchev, Strange, Piesse, and Lien (2007), Fogel, Morck, and Yeung (2008), Grøgaard et al. (2019), Knutsen et al. (2011), Rygh (2018), and Samuelson and Vickrey (1964) further note that the state as an owner and investor is typically highly diversified. This portfolio effect may allow SOEs to tolerate greater amounts of risk (such as the additional risk inherent in more generously granting trade credit). Furthermore, Benito et al. (2016), Cui and Jiang (2012), and Knutsen et al. (2011) argue that the bailout potential facilitated by state backing should also embolden SOEs to accept more risk (and thus prompt them to offer larger amounts of trade credit). Moreover, ownership by the state may be consistent with “patient capital” as described by Redding (2005). Specifically, Musacchio et al. (2015), Benito et al. (2016), and Rygh (2018) note that financial support from the soft budget constraint, by mitigating the SOE’s threat of bankruptcy, allows state-owned firms the latitude to pursue projects with longer-term payoffs. That is, the soft budget constraint endows the SOE with the “patience” to undertake investments that may be deemed excessively risky by private firms (which may have more myopic requirements for short-term financial results). Similarly, Bass and Chakrabarty (2014), Benito et al. (2016), Filatotchev et al. (2007), and Grøgaard et al. (2019) recognize that differences in SOEs’ time horizons may contribute to differences in risk preferences, allowing SOEs to engage in projects that POEs may find too risky.

Different accountability

Krueger (1990) notes that a lack of transparency may contribute to inefficiency and posits that SOEs in general often face less public scrutiny than POEs. More specifically, this insulation from investor oversight may motivate SOEs to more generously grant trade credit.

Additionally, while accountability for SOEs may be lower than for POEs, the granting of trade credit, in general, may also be subject to lower public scrutiny. In other words, of the various methods a state could use to funnel capital to a favored firm, trade credit is among the least likely to draw public ire (or to have negative implications for the SOE or its associated politicians). To illustrate, we briefly outline three specific ways a government can inject cash into a favored firm: (1) a direct grant from the state, (2) a loan from a government-owned bank (GOB), or (3) trade credit provided by an SOE.

A direct grant from the state is usually highly conspicuous and could invite a great deal of public surveillance. For example, Krueger (1990) explores the role of accountability in improving the efficiency of SOEs. She contends that delineating the amount of government subsidies channeled to SOEs as a line item in the federal budget would make the support more publicly apparent. She also argues that the resultant public “embarrassment” for the SOE and/or the affiliated politicians would encourage performance improvements.

Loans from a GOB may also lead to negative consequences, mostly because of the regulatory scrutiny that banks face. Bank loans in which the borrower defaults or is delinquent attract more attention than accounts receivable that are unpaid or are in arrears. Acharya, Eisert, Eufinger, and Hirsch (2019) and Caballero, Hoshi, and Kashyap (2008) describe the repercussions for the state if it chooses to channel funds to favored firms through loans from GOBs. Specifically, Acharya et al. (2019) and Caballero et al. (2008) note that a bad bank loan invites increased regulatory monitoring, necessitates larger provisioning, and requires the commitment of additional capital.

In contrast, the granting of trade credit by a non-bank SOE would not attract the same amount of potentially negative attention. Although non-bank SOEs must provide an allowance for doubtful accounts, the public backlash would be much less intense than it would be for a bank (because a bank must abide by strict regulations, such as those mandated by the Basel Accords).

Therefore, we argue that trade credit provision by SOEs (relative to other methods of state-sponsored financial subsidies) allows a government to more effectively camouflage funding channeled to favored entities. That is, accounts receivable from SOEs may represent a form of “stealth financing,” which should generally attract less scrutiny from market participants and political opponents. We expect that this stealth aspect of trade credit provision may provide further motivation for SOEs to grant larger amounts of accounts receivable.

The above discussion leads to our hypothesis as to how state ownership affects the provision of trade credit by NPFs. Stated formally,

Hypothesis 1:

The proportional level of state ownership will affect the amount of trade credit offered by the NPF. Higher (lower) state ownership in NPFs will be associated with more (less) trade credit.

Macro (Country-Level) Boundary Conditions

While the discussion above suggests that the financing advantage theory, emphasized in the finance literature, offers an explanation of the credit-granting decisions of SOEs, there are other factors to consider. In fact, SOEs’ choices to grant trade credit are driven by opportunities and motivations, which in turn are related to a nation’s institutional environment. Examining the conditional effects of state ownership on trade credit (i.e., variations in Hypothesis 1) helps explain why the relation between state ownership and trade credit varies across nations.

To guide our investigation as to how macro (or country-level) factors may affect credit-granting decisions by state-owned firms, we follow the analytical framework developed by institutional economists such as North (1990) and Williamson (2000). These institutional typologies consider how formal and informal institutions influence corporate behavior. As summarized by Boubakri et al. (2016), the Williamson (2000) framework is embodied within a four-tiered hierarchy. Level 1 comprises informal institutions (e.g., national culture) that vary across countries and impose informal constraints on decision-making (Williamson, 1998). Level 2 represents the formal institutions (e.g., the legal environment). Level 3 houses the governance institutions (which oversee the specific design of contracts). Level 4 consists of resource allocation and employment (e.g., the domain of neoclassical marginal analysis). Inspired by Williamson’s framework, we next discuss how formal (such as financial, legal, political, and informational) and informal (such as national culture and social) institutions may influence the trade credit-granting decisions of SOEs at the corporate level.

From a macro (country-level) perspective, we propose boundary conditions to reflect each nation’s financial, legal, informational, political, cultural, and social environments. By identifying how a country-level institutional context affects the formulation of credit-granting decisions by SOEs, we offer additional important evidence as to how and why institutions matter.

In the following section, we consider how the nation’s institutional environment may shape the opportunities and the motivations for SOEs to offer trade credit. We begin by considering the SOE’s opportunities.

Institutional Factors that Affect the SOE’s Opportunities to Extend Trade Credit

Financial environment

Our focus on the financing advantage theory of trade credit naturally suggests that a nation’s financial environment is an important institutional boundary condition that affects the relation between state ownership and trade credit. That is, financing advantages may be especially valuable for SOEs operating in less developed financial markets. A well-functioning financial market is crucial to the optimal allocation of resources and is a key contributor to economic growth. Thus, in settings where firms have limited access to capital, SOEs can help overcome these difficulties by providing an alternative source of funds (such as trade credit).

We argue that SOEs’ financing advantages (notably, the augmentation provided by the soft budget constraint) are especially valuable for those operating in less developed financial markets. Fisman and Love (2003), Demirgüç-Kunt and Maksimovic (2001), Cull, Xu, and Zhu (2009), Ge and Qiu (2007), and Petersen and Rajan (1997) support the notion that implicit borrowing in the form of trade credit can be an alternative source of funds in these environments. In our context, firms with greater access to private credit should have lower demand for alternative sources of financing (such as trade credit extended by SOEs). More directly, Robb and Robinson (2014) and Cosh, Cumming, and Hughes (2009) use survey data to identify that trade credit is not always the firm’s first choice as a source of financing. Therefore, if funding opportunities abound, finance-seeking firms have numerous options and the need for the state to extend its “helping hand” (through SOE-facilitated trade credit) is reduced. Accordingly, we expect SOEs to provide less trade credit if a nation’s financial market is more developed and thus offers more funding opportunities for borrowers.5 Our next hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 2.1:

In nations with less well-developed financial markets, there will be a stronger positive relation between state ownership and trade credit provision.

Legal environment

Based on the seminal work of La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny (1997, 1998), we expect that a nation’s legal environment is a potentially significant country-level boundary condition that contributes to cross-national differences in corporate decision-making. Evidence from La Porta et al. (1997), Levine (1998, 1999), and Djankov, McLiesh, and Shleifer (2007) indicates that stronger legal protection of shareholders and creditors is associated with larger and deeper capital markets. Because the granting of trade credit is a form of lending, we focus on the legal rights of creditors. Overall, since funding opportunities should be less available in nations with weaker legal protection of creditors, we expect a negative relation between the strength of creditor rights and the provision of trade credit by SOEs. Accordingly, our next hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 2.2:

Stronger protection of creditor rights will have a negative impact on the relation between state ownership and the provision of trade credit.

Information environment

The information environment is another country-level boundary condition that may affect the opportunities for SOEs to extend trade credit. Specifically, Rygh (2018) argues that state ownership may become more advantageous as the writing of complete contracts becomes increasingly difficult. To the extent that complete contracting is challenging in a more opaque information environment, we would expect that a weaker information environment would contribute to a larger role for state ownership (and thus a greater amount of trade credit provision by SOEs). Conversely, in a better information environment, the contracting-based advantages of state ownership should diminish, thereby lessening SOEs’ role as providers of trade credit. Accordingly, we form Hypothesis 2.3 regarding the impact of the country-level boundary condition relating to the nation’s information environment:

Hypothesis 2.3:

In countries with a stronger information environment, there will be a weaker relation between state ownership and the provision of trade credit.

Institutional Factors that Affect the SOE’s Motivations to Extend Trade Credit

To grant trade credit, a firm must have opportunity and motivation. We next consider how the institutional environment affects the SOE’s motivations to offer trade credit.

Political environment

Political motivations should affect the relation between state ownership and the provision of trade credit. We consider various institutional settings in which the motivations of SOEs to advance political agendas by preferentially allocating trade credit should differ. Specifically, we examine the role of a country’s political orientation (i.e., left- versus right-wing government).

Beck, Clarke, Groff, Keefer, and Walsh (2001) and Megginson, Nash, Netter, and Poulsen (2004) posit that left-wing governments exert more state control over a nation’s economy. Additionally, Besley and Case (2003) and Jager (2017) identify that government spending is higher when a left-wing political party is in power. Heightened levels of government spending increase the likelihood of subsidies for SOEs, which make possible more extensive financing advantages for SOEs, which in turn leads to a greater ability of SOEs to extend trade credit. Accordingly, left-wing governments should have greater motivation to use SOEs to grant larger amounts of trade credit. Our hypothesis regarding this effect is as follows:

Hypothesis 3.1:

In nations with a more left-oriented political environment, there will be a stronger positive relation between state ownership and trade credit provision.

Cultural environment

A central tenet of the privatization literature (e.g., Megginson & Netter, 2001) is that changes in ownership should cause changes in motivation. Larger proportions of state ownership should lead to greater motivation to pursue non-economic objectives. Larger proportions of private ownership should lead to greater motivation to pursue value maximization. Our analysis of the provision of trade credit allows us to explore this relation more deeply. First, we focus on the motivations of SOEs to engage in activities that enhance social welfare. To provide evidence that SOEs tailor credit-granting decisions to engineer socially desirable outcomes, we consider different institutional settings where we expect the motivations to preferentially allocate trade credit to vary. Our next hypothesis captures how a nation’s cultural environment affects credit-granting by SOEs.6

Prior research suggests that countries with collectivist national cultures are associated with governments committed to increased state control, greater intervention in the economy, and stronger emphasis on fulfilling social expectations (e.g., Boubakri, Cosset, & Saffar, 2017; Boubakri et al., 2016; Boubakri, Guedhami, Kwok, & Wang, 2019; House, Javidan, Hanges, & Dorfman, 2002). Because government motivations to intervene in economic activity should be stronger in countries with a more collectivist society, SOEs should grant larger amounts of trade credit in those countries. This leads to Hypothesis 3.2:

Hypothesis 3.2:

In nations with a more collectivist culture, there will be a stronger positive relation between state ownership and trade credit provision.

Social environment

The privatization literature (e.g., Boycko, Shleifer, & Vishny, 1996; Megginson & Netter, 2001; Shapiro & Willig, 1990; Shirley, 1999) identifies that the SOE’s adherence to social objectives contributes to diminished financial and operating performance (relative to that of privately owned firms). More recently, Grøgaard et al. (2019) insightfully demonstrate that commitment to social (non-economic) goals is a key area of differentiation between the performance of SOEs and POEs. It follows that the rigor in which social goals are pursued should be contingent on the proportion of state ownership. That is, firms with greater levels of state ownership should have stronger motivation to pursue social objectives and should be more devoted to the “double bottom line” (Inoue et al., 2013).

The pursuit of social objectives is also emblematic of the “patient” capital provided by the government as a shareholder (Inoue et al., 2013; Lazzarini & Musacchio, 2018; Redding, 2005). These authors specifically note that stability of employment is a social objective typically associated with “patient” capital. Therefore, “patient” providers of capital (e.g., the state) should be willing to put forth more effort to support employment stability, such as extending more trade credit during times of economic stress. However, as privatization reduces the level of state ownership, that “patience” may wear thin as the resultant shift towards private ownership decreases the firm’s propensity to liberally grant trade credit and increases its commitment to value maximization.

Furthermore, the need for the social engineering that is frequently attributed to SOEs may be intensified if a country faces more dire social and economic conditions. Lazzarini and Musacchio (2018), focusing on circumstances that may whet a government’s appetite for intervention, identify that periods of economic turmoil may spur governments to attach even greater emphasis to achieving social objectives (such as maintaining employment stability during periods of financial downturn). Thus, we follow Lazzarini and Musacchio (2018) and contend that, in countries plagued by high unemployment, SOEs should have stronger motivation to foster employment security by supporting the economy through the more liberal granting of trade credit. Hypothesis 3.3 is as follows:

Hypothesis 3.3:

In nations with greater social needs (such as high levels of unemployment), there will be a stronger positive relation between state ownership and trade credit provision.

Micro (Firm-Level) Boundary Conditions

We also recognize that micro (or firm-level) factors may affect the opportunities and motivations that shape the SOE’s credit-granting decisions, shedding additional light on variations in the relation between state ownership and trade credit provision.

Level of state ownership (majority vs. minority)

We build upon Musacchio, Lazzarini, and Aguilera’s (2015) work, which notes that different forms of state capitalism lead to different types of economic outcomes. Specifically, we capitalize on their more nuanced perspective to gauge how the provision of trade credit may vary according to the different typologies of state capitalism. We draw from Grøgaard et al. (2019) and Benito et al. (2016) as well. They find similarly that variance in performance can be traced to an SOE’s ownership type.

Following Benito et al. (2016), we categorize the type of state ownership based on whether the state is a majority investor (i.e., government owns more than 50% of the firm’s shares) or a minority investor (i.e., government is not the largest shareholder). As we discussed earlier, SOEs have both the opportunity (due to the financing advantages facilitated by soft-budget constraints) and the motivation (due to differences in goals, risk profiles, and public accountability) to grant more trade credit. Moreover, the level of state ownership calibrates the magnitude of the SOE’s opportunities and motivations for granting trade credit.

Regarding the motivations that underpin credit-granting decisions by SOEs, a reduction in state ownership should serve to relax the grip of the state’s “grabbing hands”. Specifically, Benito et al. (2016), Grøgaard et al. (2019), Inoue et al. (2013), and Lazzarini and Musacchio (2018) contend that a decrease in state ownership reduces the likelihood of government interference. This precipitates a shift away from non-economic goals (i.e., political and/or social objectives) and facilitates a heightened focus on profitability and other ambitions more consistent with private ownership. As a result, the motivations to more liberally extend trade credit in efforts to achieve political or social goals will be reduced.

The opportunities to extend trade credit should also change with changes in the level of state ownership. Benito et al. (2016) and Musacchio et al. (2015) note that a reduction in state ownership typically constricts the flow of government-sponsored financial support, thus diverting the tributary of the financing advantage. That is, as state ownership decreases, the soft budget constraint (which is the source of the financing advantage for SOEs) will begin to “harden”. This reduces the opportunities for more extensive granting of trade credit.

As a result, with larger degrees of state ownership, the credit-granting opportunities should be greater and the motivations should be stronger. Accordingly, Hypothesis 4.1 proposes the following relation between the extent of state ownership and the provision of trade credit.

Hypothesis 4.1:

SOEs with majority (minority) state ownership will grant higher (lower) amounts of trade credit.

Extent of internationalization

An SOE’s degree of internationalization is another firm-level factor to consider when evaluating the determinants of credit-granting. By definition, a firm experiencing increased internationalization should have a higher level of foreign sales and/or foreign ownership, both of which should reduce the SOE’s motivations to grant trade credit.

First, as foreign sales increase, the SOE’s non-economic motivations to extend trade credit should decrease. Sapienza (2004), Shleifer (1998), and Shleifer and Vishny (1994) document that governments use SOEs to pursue political and social goals (e.g., maximizing employment, endowing favored enterprises, channeling resources to constituents). Politicians engage in such machinations ostensibly to secure votes or, more broadly, foster goodwill amongst the citizenry. In this paper, we argue that one way SOEs attempt to fulfill these types of objectives is by providing liquidity through the more liberal granting of trade credit. However, granting trade credit to a foreign customer (i.e., foreign sales) would generate no political or social benefit in the home country of the SOE.7 Foreign customers do not vote in domestic elections; supporting employment in foreign countries does not provide social benefits in the SOE’s home country. Therefore, if the SOE grants more trade credit in an effort to fulfill social/political goals (and those goals are specific to the domestic market), SOEs with more international sales should offer less overall trade credit.

Second, relative to domestic investors, foreign shareholders should have different expectations regarding the firm’s performance. These different expectations of foreign owners should temper the SOE’s motivations to use credit-granting to engineer specific political or social outcomes. Foreign investors should be ambivalent to the SOE’s domestic objectives (i.e., political and social goals). Instead, foreign owners should be more motivated by profitability. Providing evidence consistent with an enhanced focus on profitability, D’Souza, Megginson, and Nash (2007), Brown, Earle, and Telegdy (2007), and Djankov and Murrell (2002) find that having greater foreign ownership contributed to stronger increases in the financial and operating performance of newly privatized firms. Therefore, by shifting focus from non-economic goals to profit maximization, foreign ownership should affect the SOE’s credit-granting decisions.

Thus, internationalization should weaken the SOE’s motivations to pursue political and/or social objectives (which, in turn, should weaken the motivations to extend trade credit). This leads to Hypothesis 4.2:

Hypothesis 4.2:

Increasing the extent of internationalization will have a negative impact on the relation between state ownership and trade credit provision.

SAMPLE, VARIABLES, AND DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS

Sample Selection

We obtain a sample of privatized firms from Chen et al. (2018), which is constructed based on data from Privatization Barometer, Thomson Reuters, SDC Platinum Global New Issues, and SDC Platinum Mergers and Acquisitions databases. Our data consist of 574 firms from 64 countries privatized during 1981–2014. This sample compares favorably with those used in recent studies of privatized firms, such as Borisova and Megginson (2011), with a sample of 60 firms from 14 countries, Boubakri et al. (2013), with 385 firms from 57 countries, and Boubakri et al. (2020), with 473 firms from 53 countries.

Because our ownership data track the change in government shareholdings after the first privatization, we are able to analyze the time-varying effect of state ownership on trade credit. Moreover, these data cover firms from countries with diverse institutional environments, which allow us to investigate the heterogeneous effects of state ownership on trade credit and to explore the effects of country-level boundary conditions.

We match the sample of NPFs with financial information from Compustat Global. Due to the nature of the banking business (i.e., accepting deposits, making loans), trade credit has a different connotation for firms in the financial services industry. Accordingly, we exclude firms with four-digit Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) codes between 6000 and 6999. We also omit observations with incomplete data for our key variables or with missing SIC codes. These filters yield a sample of 5503 firm-year observations.

Table 1 summarizes our sample distribution by industry, year, region, and country in Panels A, B, C, and D, respectively. Panel A shows the distribution across Fama–French’s (1997) 48 industries. Approximately 17% of our firms are utilities, 13% are in transportation, and 12% are in communication.8 Panel B presents the number of firm-year observations and the distribution of firms privatized from 1981 to 2014. We observe significant growth in privatizations throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Panel C reveals that the sample is widely distributed across regions, with approximately 64% of our observations located in Europe and Central Asia, 23% in East and South Asia and the Pacific, 10% in Latin America and the Caribbean, and 3% in Africa and the Middle East. Relatedly, Panel D shows that our sample consists of both developed and developing countries (exhibiting a wide heterogeneity of institutional environments). These data allow us to explore how country-level boundary conditions influence the effect of state ownership on trade credit provision.9

Table 1.

Distribution of the sample of newly privatized firms

| Industry | Obs. | Percentage | Firms | Percentage | Industry | Obs. | Percentage | Firms | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: By industry | |||||||||

| Aircraft | 79 | 1.44 | 8 | 1.39 | Healthcare | 1 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.17 |

| Apparel | 21 | 0.38 | 2 | 0.35 | Machinery | 147 | 2.67 | 14 | 2.44 |

| Automobiles and trucks | 114 | 2.07 | 10 | 1.74 | Measuring and control equipment | 22 | 0.40 | 2 | 0.35 |

| Beer and liquor | 66 | 1.20 | 8 | 1.39 | Non-metallic and industrial metal mining | 95 | 1.73 | 9 | 1.57 |

| Business service | 76 | 1.38 | 8 | 1.39 | Petroleum and natural gas | 405 | 7.36 | 40 | 6.97 |

| Business supplies | 36 | 0.65 | 3 | 0.52 | Pharmaceutical products | 69 | 1.25 | 6 | 1.05 |

| Candy and soda | 25 | 0.45 | 2 | 0.35 | Precious metals | 18 | 0.33 | 3 | 0.52 |

| Chemicals | 287 | 5.22 | 31 | 5.40 | Printing and publishing | 52 | 0.94 | 5 | 0.87 |

| Coal | 46 | 0.84 | 8 | 1.39 | Recreation | 15 | 0.27 | 1 | 0.17 |

| Communication | 672 | 12.21 | 66 | 11.50 | Restaurants, hotels, motels | 44 | 0.80 | 4 | 0.70 |

| Computers | 12 | 0.22 | 1 | 0.17 | Retail | 66 | 1.20 | 7 | 1.22 |

| Construction | 126 | 2.29 | 15 | 2.61 | Shipbuilding, railroad equipment | 46 | 0.84 | 5 | 0.87 |

| Construction materials | 247 | 4.49 | 26 | 4.53 | Shipping containers | 17 | 0.31 | 2 | 0.35 |

| Consumer goods | 62 | 1.13 | 6 | 1.05 | Steel works | 338 | 6.14 | 32 | 5.57 |

| Defense | 1 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.17 | Textiles | 48 | 0.87 | 5 | 0.87 |

| Electrical equipment | 63 | 1.14 | 5 | 0.87 | Tobacco products | 32 | 0.58 | 3 | 0.52 |

| Electronic equipment | 67 | 1.22 | 8 | 1.39 | Transportation | 706 | 12.83 | 75 | 13.07 |

| Entertainment | 9 | 0.16 | 1 | 0.17 | Utilities | 931 | 16.92 | 96 | 16.72 |

| Fabricated products | 44 | 0.80 | 3 | 0.52 | Wholesale | 79 | 1.44 | 13 | 2.26 |

| Food products | 159 | 2.89 | 20 | 3.48 | Other | 160 | 2.91 | 19 | 3.31 |

| Year | Obs. | Percentage | Firms | Percentage | Year | Obs. | Percentage | Firms | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel B: By privatization year | |||||||||

| 1981 | 10 | 0.18 | 1 | 0.17 | 1999 | 294 | 5.34 | 27 | 4.70 |

| 1983 | 6 | 0.11 | 1 | 0.17 | 2000 | 221 | 4.02 | 24 | 4.18 |

| 1984 | 5 | 0.09 | 1 | 0.17 | 2001 | 119 | 2.16 | 13 | 2.26 |

| 1985 | 21 | 0.38 | 2 | 0.35 | 2002 | 106 | 1.93 | 10 | 1.74 |

| 1986 | 44 | 0.80 | 4 | 0.70 | 2003 | 138 | 2.51 | 16 | 2.79 |

| 1987 | 103 | 1.87 | 7 | 1.22 | 2004 | 85 | 1.54 | 12 | 2.09 |

| 1988 | 94 | 1.71 | 8 | 1.39 | 2005 | 122 | 2.22 | 12 | 2.09 |

| 1989 | 172 | 3.13 | 12 | 2.09 | 2006 | 241 | 4.38 | 28 | 4.88 |

| 1990 | 148 | 2.69 | 15 | 2.61 | 2007 | 146 | 2.65 | 15 | 2.61 |

| 1991 | 386 | 7.01 | 32 | 5.57 | 2008 | 49 | 0.89 | 6 | 1.05 |

| 1992 | 429 | 7.80 | 46 | 8.01 | 2009 | 37 | 0.67 | 7 | 1.22 |

| 1993 | 337 | 6.12 | 35 | 6.10 | 2010 | 76 | 1.38 | 14 | 2.44 |

| 1994 | 420 | 7.63 | 42 | 7.32 | 2011 | 24 | 0.44 | 7 | 1.22 |

| 1995 | 362 | 6.58 | 38 | 6.62 | 2012 | 39 | 0.71 | 6 | 1.05 |

| 1996 | 328 | 5.96 | 33 | 5.75 | 2013 | 29 | 0.53 | 7 | 1.22 |

| 1997 | 504 | 9.16 | 49 | 8.54 | 2014 | 15 | 0.27 | 7 | 1.22 |

| 1998 | 393 | 7.14 | 37 | 6.45 | |||||

| Obs. | Percentage | Firms | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel C: By region (number of countries) | ||||

| Africa and the Middle East (9) | 180 | 3.27 | 21 | 3.66 |

| East and South Asia and the Pacific (12) | 1248 | 22.68 | 142 | 24.74 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean (8) | 571 | 10.38 | 61 | 10.63 |

| Europe and Central Asia (35) | 3504 | 63.67 | 350 | 60.98 |

| Country | Obs. | Percentage | Firms | Percentage | Country | Obs. | Percentage | Firms | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel D: By country | |||||||||

| Argentina | 110 | 2.00 | 8 | 1.39 | Lithuania | 45 | 0.82 | 6 | 1.05 |

| Australia | 29 | 0.53 | 3 | 0.52 | Malaysia | 146 | 2.65 | 16 | 2.79 |

| Austria | 119 | 2.16 | 11 | 1.92 | Mexico | 40 | 0.73 | 4 | 0.70 |

| Belgium | 39 | 0.71 | 4 | 0.70 | Morocco | 24 | 0.44 | 2 | 0.35 |

| Brazil | 293 | 5.32 | 33 | 5.75 | Netherlands | 18 | 0.33 | 3 | 0.52 |

| Bulgaria | 3 | 0.05 | 1 | 0.17 | New Zealand | 43 | 0.78 | 5 | 0.87 |

| Chile | 41 | 0.75 | 4 | 0.70 | Nigeria | 14 | 0.25 | 3 | 0.52 |

| China | 1019 | 18.52 | 102 | 17.77 | Norway | 28 | 0.51 | 4 | 0.70 |

| Colombia | 36 | 0.65 | 4 | 0.70 | Oman | 3 | 0.05 | 1 | 0.17 |

| Croatia | 46 | 0.84 | 4 | 0.70 | Pakistan | 175 | 3.18 | 21 | 3.66 |

| Czech Republic | 28 | 0.51 | 5 | 0.87 | Peru | 36 | 0.65 | 6 | 1.05 |

| Denmark | 31 | 0.56 | 2 | 0.35 | Philippines | 40 | 0.73 | 6 | 1.05 |

| Egypt | 28 | 0.51 | 4 | 0.70 | Poland | 326 | 5.92 | 41 | 7.14 |

| Finland | 148 | 2.69 | 12 | 2.09 | Portugal | 73 | 1.33 | 6 | 1.05 |

| France | 171 | 3.11 | 20 | 3.48 | Romania | 23 | 0.42 | 4 | 0.70 |

| Germany | 169 | 3.07 | 12 | 2.09 | Russia | 62 | 1.13 | 8 | 1.39 |

| Ghana | 2 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.17 | Saudi Arabia | 6 | 0.11 | 1 | 0.17 |

| Greece | 106 | 1.93 | 10 | 1.74 | Serbia | 3 | 0.05 | 1 | 0.17 |

| Hong Kong | 15 | 0.27 | 2 | 0.35 | Singapore | 67 | 1.22 | 6 | 1.05 |

| Hungary | 127 | 2.31 | 11 | 1.92 | Slovakia | 17 | 0.31 | 2 | 0.35 |

| India | 311 | 5.65 | 34 | 5.92 | South Africa | 24 | 0.44 | 2 | 0.35 |

| Indonesia | 151 | 2.74 | 11 | 1.92 | South Korea | 84 | 1.53 | 7 | 1.22 |

| Ireland | 47 | 0.85 | 3 | 0.52 | Spain | 135 | 2.45 | 12 | 2.09 |

| Israel | 40 | 0.73 | 3 | 0.52 | Sri Lanka | 135 | 2.45 | 17 | 2.96 |

| Italy | 195 | 3.54 | 21 | 3.66 | Sweden | 73 | 1.33 | 8 | 1.39 |

| Jamaica | 13 | 0.24 | 1 | 0.17 | Switzerland | 18 | 0.33 | 1 | 0.17 |

| Japan | 42 | 0.76 | 4 | 0.70 | Thailand | 55 | 1.00 | 7 | 1.22 |

| Jordan | 41 | 0.75 | 4 | 0.70 | Turkey | 157 | 2.85 | 12 | 2.09 |

| Kazakhstan | 18 | 0.33 | 2 | 0.35 | United Kingdom | 130 | 2.36 | 15 | 2.61 |

| Kenya | 23 | 0.42 | 2 | 0.35 | Venezuela | 2 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.17 |

| Kuwait | 3 | 0.05 | 1 | 0.17 | Vietnam | 2 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.17 |

| Latvia | 50 | 0.91 | 5 | 0.87 | Zimbabwe | 5 | 0.09 | 1 | 0.17 |

The table presents the distribution of the sample of privatized firms. The full sample contains 5503 firm-year observations for 574 firms privatized in 64 countries over the 1981–2014 period. Panel A reports the number of observations by industry (based on 48 industry groupings in Fama & French, 1997). Panel B reports the number of observations by privatization year. Panel C presents the number of observations by region (based on World Bank group classification). Panel D provides the sample distribution by country.

Variables

Trade credit

Following Petersen and Rajan (1997), we define trade credit (Trade Credit) as trade receivables scaled by total sales. We obtain trade credit data from Compustat Global, where trade receivables is the amount owed by customers for goods and services sold in the ordinary course of business.10,11 The “Appendix” provides definitions and data sources for all variables.

State ownership

Our primary measure of state ownership (State Ownership) is the percentage of shares held by the government. For robustness, we also use State Control, an indicator variable that equals 1 for firms in which the government retains control (i.e., owns more than 50% of the firm’s shares).

Variables used to test country-level boundary conditions hypotheses

We obtain measures of private credit (Private Credit) from World Development Indicators. This variable is defined as loans provided to the private sector by financial corporations divided by GDP. We measure Government Ownership of Banks at the country level using data from Barth, Caprio, and Levine (2013). This variable reflects the percentage of a banking system’s assets in banks that are 50% or more government-owned. While Private Credit is a measure of financing available to the private sector, Government Ownership of Banks is a proxy for credit to SOEs. We use these two measures to test Hypothesis 2.1.

To test Hypothesis 2.2, we measure the legal protection of creditors (Creditor Rights) with a dummy variable that indicates whether secured creditors are able to seize collateral after the reorganization petition is approved (i.e., “no automatic stay”). La Porta et al. (1998) assert that the right to repossess collateral may be the most important of the legal protections for creditors. They argue that creditors are paid because of the legal rights to claim collateral. Mann (2018) provides empirical support for this notion by verifying that an increase in creditors’ legal claims on collateral is associated with an increase in the use of debt. This is also confirmed by Costello (2019), who specifically evaluates the impact of creditor rights on trade credit provision. Costello (2019) and Longhofer and Santos (2003) verify the significance of this right by providing evidence that an increase in collateral protection is associated with an increase in the provision of trade credit.

Of the four legal protections of creditors (as listed by La Porta et al., 1998), the “no automatic stay” stipulation most directly relates to the rights to reclaim and liquidate collateral. Therefore, we expect the “no automatic stay” clause to have the most profound effect on the relation between state ownership and trade credit provision. We obtain this variable from Djankov et al. (2007).

When evaluating Hypothesis 2.3, we follow El Ghoul and Zheng (2016) and add a variable (Information Sharing) to indicate whether private credit registries are available in each country. We obtain this metric from Djankov et al. (2007).

We test Hypothesis 3.1 by including the political orientation variable Left, which indicates whether the ruling party’s economic orientation is communist, socialist, social democratic, or left-wing. This variable is from the Database of Political Institutions (2012). Furthermore, we use a measure of collectivism from Hofstede (1984) to examine the role of a nation’s cultural environment (Hypothesis 3.2). We obtain this measure by subtracting Hofstede’s individualism score from 100, so that higher values indicate a greater degree of collectivism. To measure a country’s social environment (Hypothesis 3.3), we use the unemployment rate (Unemployment (%)) obtained from EIU Country data.

Variables used to test firm-level boundary conditions hypotheses

We measure the level of state ownership with two indicator variables. We define State as a Majority Investor as 1 when a government holds more than 50% of shares in a privatized firm, and 0 otherwise. State as a Minority Investor is a dummy variable that equals 1 if any shareholder holds more shares than the government, and 0 otherwise. We use these two ownership variables to test Hypothesis 4.1.

To test Hypothesis 4.2, we consider two variables related to an SOE’s extent of internationalization. Cross-listing is a dummy variable indicating whether a firm is cross-listed in the U.S. equity market.12 We also define Foreign Sales as whether a firm has revenues from foreign sales. We obtain this metric from FactSet.

Control variables

Following prior literature (Giannetti et al., 2011; Love, Preve, & Sarria-Allende, 2007; Petersen & Rajan, 1997), we control for several firm- and country-level variables related to trade credit. At the firm level, we include firm size (Log(Sales)); natural logarithm of total sales in $U.S. millions; profit (Return on Sales); ratio of income before extraordinary items to total sales; cash holdings (Cash Holdings); ratio of cash and short-term investments to total assets; fixed assets (Fixed Assets); ratio of total property, plant, and equipment to total assets; sales growth (Sales Growth); growth rate of total sales; gross profit margin (Gross Profit Margin); ratio of total sales less cost of goods sold to total sales; and debt-equity ratio (D/E ratio); ratio of book value of debt to book value of equity. At the country level, we include the natural logarithm of GDP per capita in constant 2000 $U.S. (Log(GDP Per Capita)) and Private Credit. Both are from World Development Indicators. To alleviate simultaneity concerns, we lag all right-hand-side variables by one year. To reduce the influence of outliers, we winsorize all financial variables at the 1% and 99% percentiles.

Descriptive Statistics

Panel A of Table 2 presents summary statistics for the key variables. On average, the ratio of trade credit to sales (Trade Credit) is around 0.17, with a standard deviation of 0.15; it varies from 0.00 to 0.86. Residual state ownership (State Ownership) has a mean (median) of 0.27 (0.13), in line with a sharp post-privatization decline in state ownership (Boubakri, Cosset, & Guedhami, 2005).

Table 2.

Summary statistics and correlation matrix

| Variable | N | Min | Mean | Median | Max | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Summary statistics | ||||||

| Trade credit | 5503 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.86 | 0.15 |

| State ownership | 5503 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.13 | 1.00 | 0.29 |

| Log (sales) | 5503 | 0.11 | 7.05 | 7.05 | 12.83 | 2.01 |

| Return on sales | 5503 | − 0.67 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.53 | 0.15 |

| Cash holdings | 5503 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.54 | 0.11 |

| Fixed assets | 5503 | 0.01 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.91 | 0.23 |

| Sales growth | 5503 | − 0.92 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 1.51 | 0.28 |

| Gross profit margin | 5503 | − 0.02 | 0.43 | 0.37 | 1.00 | 0.28 |

| D/E ratio | 5503 | 0.00 | 0.41 | 0.30 | 2.45 | 0.43 |

| Log (GDP per capita) | 5503 | 6.59 | 9.13 | 9.15 | 11.41 | 1.20 |

| Private credit | 5503 | 8.60 | 76.98 | 75.70 | 233.00 | 42.84 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel B: Correlation matrix | ||||||||||

| 1. Trade credit | 1 | |||||||||

| 2. State ownership | 0.03 | 1 | ||||||||

| 3. Log (sales) | − 0.07 | 0.10 | 1 | |||||||

| 4. Return on sales | − 0.02 | 0.07 | − 0.02 | 1 | ||||||

| 5. Cash holdings | − 0.01 | 0.12 | − 0.08 | 0.22 | 1 | |||||

| 6. Fixed assets | − 0.28 | 0.06 | − 0.01 | 0.04 | − 0.40 | 1 | ||||

| 7. Sales growth | − 0.06 | 0.05 | − 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 1 | |||

| 8. Gross profit margin | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.33 | − 0.03 | 0.19 | − 0.03 | 1 | ||

| 9. D/E ratio | − 0.08 | − 0.06 | 0.11 | − 0.16 | − 0.27 | 0.23 | − 0.01 | 0.02 | 1 | |

| 10. Log (GDP per capita) | 0.05 | − 0.28 | 0.41 | − 0.05 | − 0.16 | − 0.07 | − 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 1 |

| 11. Private credit | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.26 | − 0.02 | 0.06 | − 0.10 | − 0.07 | − 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.31 |

The table presents descriptive statistics for the key variables in our analyses. The full sample contains 5503 firm-year observations for 574 firms privatized in 64 countries over the 1981–2014 period. We winsorize all financial variables at the 1% level in both tails of the distribution. The “Appendix” provides variable definitions and sources. Panel A reports summary statistics; panel B provides the pairwise correlations among the variables.

Panel B of Table 2 reports Pearson correlation coefficients between the firm- and country-level variables. We find that Trade Credit is positively correlated with State Ownership, Gross Profit Margin, Log(GDP Per Capita), and Private Credit, and negatively associated with Log(Sales), D/E Ratio, Fixed Assets, and Sales Growth.

RESULTS

Preliminary Evidence

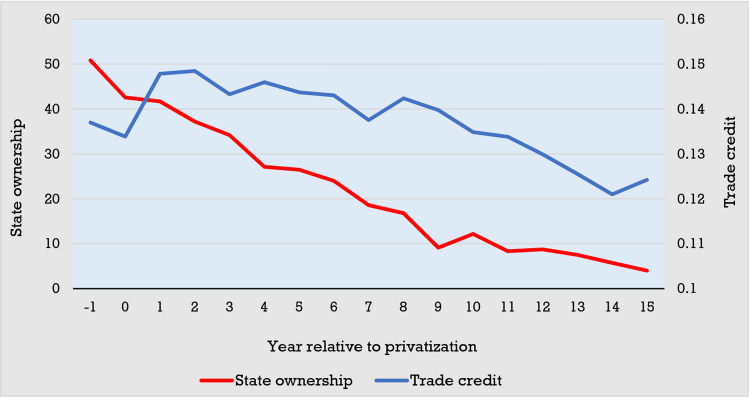

In a first attempt to understand how government ownership affects the extension of trade credit, we examine whether state ownership and trade credit provision evolve in systematic ways as the privatization process unfolds. Figure 1 plots the evolution of the mean levels of state ownership and trade credit provision from one year before the initial privatization (− 1) to 15 years (+ 15) afterwards.13 As government ownership steadily declines, trade credit provision by privatized firms also decreases over the period (− 1, + 15). Figure 1 therefore documents that NPFs tend to offer less trade credit as the state ownership share falls during privatization.14

Figure 1.

Evolution of state ownership and supply of trade credit. Figure plots the evolution (relative to privatization year) of state ownership and the supply of trade credit provided by NPFs. We define state ownership as the percentage of shares held by a government. We define trade credit as the ratio of trade receivables to total sales. Trade receivables equals amounts on open account (net of applicable reserves) owed by customers for goods and services sold in the ordinary course of business. The sample comprises 574 privatized firms from 64 countries over the 1981–2014 period.

Effect of State Ownership on Trade Credit

We next employ a multivariate analysis. Specifically, we regress Trade Credit on State Ownership, and the determinants of trade credit that we previously identified. We estimate the following regression model:

| 1 |

where i indexes firms, j indexes industries, c indexes countries, and t indexes years. FLV is a vector of firm-level controls and CLV is a vector of country-level controls. , , and are country-, industry-, and year-effects, respectively.

Table 3 reports regression results. To control for within-firm correlation, we base significance levels on robust standard errors adjusted for clustering at the firm level. In Model 1, the coefficient on State Ownership is positive and statistically significant [p value < 0.001, and 95% confidence interval (CI) between 0.031 and 0.106]. This indicates that firms provide less trade credit as state ownership decreases during privatization. This result is also economically significant: The estimated coefficient on State Ownership denotes that moving from the 25th (0.00) to the 75th (0.51) percentile results, on average, in a 20.7% increase in trade credit provision, holding all other variables at their mean values.15 Thus, in line with the preliminary results (see Figure 1), these findings support the financing advantage view of state ownership.

Table 3.

Testing Hypothesis 1: State Ownership and Trade Credit

| Variables | Basic model | Endogeneity of state ownership | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrumental variable regression 1st stage | Instrumental variable regression 2nd stage | Heckman 2nd stage | PSM | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| State ownership | 0.069 | 0.631 | 0.106 | 0.056 | |

| (0.019) | (0.277) | (0.024) | (0.024) | ||

| Deficits | − 0.008 | ||||

| (0.003) | |||||

| Log (sales) | − 0.009 | 0.038 | − 0.028 | − 0.009 | − 0.001 |

| (0.004) | (0.008) | (0.012) | (0.004) | (0.005) | |

| ROA | 0.025 | − 0.063 | 0.050 | 0.020 | 0.038 |

| (0.028) | (0.068) | (0.054) | (0.031) | (0.034) | |

| Cash holdings | − 0.126 | 0.063 | − 0.197 | − 0.121 | − 0.145 |

| (0.042) | (0.093) | (0.071) | (0.049) | (0.052) | |

| Fixed assets | − 0.144 | 0.014 | − 0.150 | − 0.125 | − 0.119 |

| (0.028) | (0.063) | (0.045) | (0.030) | (0.034) | |

| Sales growth | − 0.018 | − 0.009 | − 0.013 | − 0.016 | − 0.024 |

| (0.008) | (0.017) | (0.013) | (0.008) | (0.010) | |

| Gross profit margin | 0.045 | 0.092 | − 0.000 | 0.030 | 0.043 |

| (0.018) | (0.042) | (0.040) | (0.021) | (0.024) | |

| D/E ratio | 0.001 | − 0.072 | 0.046 | 0.003 | − 0.006 |

| (0.009) | (0.024) | (0.026) | (0.010) | (0.011) | |

| Log (GDP per capita) | 0.031 | − 0.119 | 0.075 | 0.051 | − 0.022 |

| (0.021) | (0.012) | (0.035) | (0.024) | (0.049) | |

| Private credit | 0.000 | 0.001 | − 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Lambda | 0.030 | ||||

| (0.008) | |||||

| Constant | − 0.051 | 1.213 | − 0.320 | − 0.221 | 0.401 |

| (0.185) | (0.170) | (0.287) | (0.215) | (0.425) | |

| Country fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 5503 | 4255 | 4255 | 4003 | 3152 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.387 | 0.271 | 0.648 | 0.430 | 0.420 |

The table shows the regression results relating state ownership to trade credit. The dependent variable is 100 times the ratio of trade receivables to total sales. Trade receivables equals amounts on open account (net of applicable reserves) owed by customers for goods and services sold in the ordinary course of business. We lag all independent variables by one year. The “Appendix” provides variable definitions and sources. The full sample contains 5503 firm-year observations from 574 firms privatized in 64 countries. We winsorize all financial variables at the 1% level in both tails of the distribution. Regressions include country dummy variables, industry dummy variables (based on 48 industry groupings in Fama & French, 1997), and year dummy variables. Robust standard errors in parentheses below each coefficient are clustered at the firm level.

Turning to the control variables, we find that the coefficient on Log(Sales) loads negatively (p value = 0.022) and is statistically significant. Thus, as observed by El Ghoul and Zheng (2016), smaller firms offer a higher proportion of sales on credit. Next, consistent with Giannetti et al. (2011), we identify that the coefficient on Fixed Assets is negative and significant (p value = 0.000). The coefficients on Cash Holdings and Sales Growth are also negative and statistically significant (p values of 0.003 and 0.020, respectively). This indicates that, when firms hold less internal cash or face a decline in sales, they offer more trade credit. El Ghoul and Zheng (2016) and Petersen and Rajan (1997) similarly recognize these characteristics and attribute these relations to financially struggling firms loosening credit standards and extending trade credit in an effort to stem decreasing sales. Finally, the coefficient on Gross Profit Margin is positive and significant (p value = 0.014), which suggests that firms with a larger profit margin offer more trade credit.16

One potential concern with the benchmark regression results in Model 1 is that the level of state ownership may not be exogenous. In a privatization context, Megginson and Netter (2001) note that sample selection bias can occur. For example, Bortolotti and Faccio (2009) provide evidence that governments are more likely to first privatize those firms that are more profitable and valuable. As such, poorly performing firms, which may tend to offer more trade credit to offset declining sales, are likely to have higher state ownership.17 Also, the relation between state ownership and trade credit could be driven by unobserved determinants of trade credit that are correlated with residual state ownership.

In Models 2 and 3, we address endogeneity concerns using two-stage instrumental variables (Borisova & Megginson, 2011; Boubakri et al., 2013; Guedhami, Pittman, & Saffar, 2009). We use a country’s government deficits (Deficits) as an instrument for state ownership. We argue that our instrument satisfies the relevance condition because governments with high deficits are more likely to sell their holdings of SOEs (Borisova & Megginson, 2011; Ramamurti, 1992). Furthermore, we contend that our instrument satisfies the exclusion restriction because Deficits is unlikely to directly affect trade credit provision, other than through state ownership.

In the first-stage regression (Model 2), we find that Deficits is negatively associated with residual state ownership (p value = 0.016). This is consistent with the idea that revenues from privatization could induce fiscally challenged governments to sell more state ownership. We also find that the Kleibergen and Paap (2006) rk LM statistic for the underidentification test is 5.287, with a p value of 0.022. This indicates that the instruments are relevant and correlated with the endogenous variable. The Kleibergen–Paap rk Wald F statistic for the weak identification test is 26.084, while Stock and Yogo’s (2005) critical value at 10% is 16.38, rejecting the null hypothesis that the instrumental variable is only weakly related to the endogenous variable.

Model 3 reports the results of the second-stage regression. We find that the coefficient on State Ownership enters positively and is statistically significant (p value = 0.023). Thus, our main results are statistically unchanged when we use instrumental variable regressions.18,19

Another concern is that residual government ownership may be influenced by firm characteristics, which in turn affect a firm’s trade credit policy. In Models 4 and 5, we address this issue by using a Heckman two-stage selection analysis and propensity score matching (PSM), respectively. Under the Heckman approach, we first use a probit model to predict whether governments retain control over privatized firms.20 We regress State Control on Deficits, the full set of control variables, and country, industry, and year fixed effects (as in Model 1 of Table 3). In the second-stage regression, we include the inverse Mills ratio (Lambda), which we estimate from the first-stage regression, as an additional control variable. The results in Model 4 continue to show that State Ownership is positively and significantly associated with Trade Credit (p value < 0.001). In addition, Lambda loads positively and is statistically significant (p value < 0.001), indicating some selection bias.

Next, we use PSM to randomize the sample selection procedure. Using observed firm- and country-level characteristics, we match state-controlled firms with non-state-controlled firms.21 Initially, we use the same probit model as in the first stage, under the Heckman two-stage selection approach. We then match firms with the closest propensity score. In the second stage (Model 5), we estimate the regression using the matched sample. The coefficient on State Ownership is positive and statistically significant (with p value < 0.001). These results are consistent with our main analysis, with the instrumental variables analysis, and with the Heckman two-stage selection analysis.

In summary, the results in Table 3 are consistent with the financing advantage theory (Hypothesis 1) of state ownership, indicating that firms are likely to provide more trade credit as government ownership increases. These findings continue to hold when we address endogeneity concerns.

Role of Country-Level Boundary Conditions on the Relation Between State Ownership and Trade Credit

We next consider how country-level boundary conditions may affect the relation between state ownership and trade credit provision.22 We first focus on the role of a nation’s level of financial market development. To gauge the strength of demand for alternative sources of funding (such as trade credit), we introduce several proxies for financial market development. In Model 1 of Table 4, we use Private Credit, which captures the ease of access to financing for all borrowers. We regress Trade Credit on State Ownership, its interaction with Private Credit, and the controls.

Table 4.

Testing macro-level boundary conditions on the relation between state ownership and trade credit: financial, legal, information, political, cultural, and social environments

| Hypothesis 2.1 Financial environment |

Hypothesis 2.2 Legal environment |

Hypothesis 2.3 Information environment |

Hypothesis 3.1 Political environment |

Hypothesis 3.2 Cultural environment |

Hypothesis 3.3 Social environment |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

| State ownership | 0.113 | 0.031 | 0.069 | 0.202 | − 0.015 | − 0.051 | 0.013 |

| (0.031) | (0.025) | (0.009) | (0.049) | (0.036) | (0.061) | (0.035) | |

| State ownership × private credit | − 0.001 | ||||||

| (0.000) | |||||||

| Government ownership of banks | − 0.063 | ||||||

| (0.029) | |||||||

| State ownership × government ownership of banks | 0.140 | ||||||

| (0.059) | |||||||

| Creditor rights | 0.004 | ||||||

| (0.005) | |||||||

| State ownership × creditor rights | − 0.042 | ||||||

| (0.015) | |||||||

| Information sharing | 0.064 | ||||||

| (0.022) | |||||||

| State ownership × information sharing | − 0.168 | ||||||

| (0.051) | |||||||

| Left | − 0.067 | ||||||

| (0.022) | |||||||

| State ownership × left | 0.142 | ||||||

| (0.060) | |||||||

| Collectivism | − 0.001 | ||||||

| (0.000) | |||||||

| State ownership × collectivism | 0.002 | ||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||

| Unemployment (%) | 0.002 | ||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||

| State ownership × unemployment (%) | 0.007 | ||||||

| (0.004) | |||||||

| Log (sales) | − 0.009 | − 0.007 | − 0.007 | − 0.007 | − 0.008 | − 0.005 | − 0.009 |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.001) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.004) | |

| ROA | 0.026 | 0.037 | 0.016 | 0.015 | 0.012 | 0.075 | 0.026 |

| (0.028) | (0.030) | (0.018) | (0.029) | (0.030) | (0.036) | (0.029) | |

| Cash holdings | − 0.126 | − 0.167 | − 0.149 | − 0.148 | − 0.157 | − 0.183 | − 0.123 |

| (0.042) | (0.042) | (0.020) | (0.041) | (0.041) | (0.055) | (0.044) | |

| Fixed assets | − 0.143 | − 0.133 | − 0.168 | − 0.161 | − 0.159 | − 0.183 | − 0.147 |

| (0.028) | (0.027) | (0.011) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.029) | (0.029) | |

| Sales growth | − 0.017 | − 0.018 | − 0.024 | − 0.020 | − 0.023 | − 0.029 | − 0.015 |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.007) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.009) | (0.008) | |

| Gross profit margin | 0.043 | 0.043 | 0.057 | 0.051 | 0.050 | 0.048 | 0.037 |

| (0.018) | (0.021) | (0.009) | (0.019) | (0.019) | (0.024) | (0.019) | |

| D/E ratio | 0.000 | − 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.019 | 0.001 |

| (0.009) | (0.010) | (0.005) | (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.014) | (0.009) | |

| Log (GDP per capita) | 0.032 | − 0.030 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 | − 0.002 | 0.035 |

| (0.021) | (0.040) | (0.002) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.009) | (0.021) | |

| Private credit | 0.000 | 0.000 | − 0.000 | 0.000 | − 0.000 | − 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Constant | − 0.063 | 0.523 | 0.088 | 0.019 | 0.120 | 0.453 | − 0.082 |

| (0.184) | (0.359) | (0.028) | (0.073) | (0.068) | (0.123) | (0.190) | |

| Country fixed effects | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 5503 | 3826 | 5503 | 3798 | 5488 | 3024 | 5150 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.389 | 0.420 | 0.308 | 0.319 | 0.316 | 0.335 | 0.387 |

The table shows the regression results considering the potential moderating role of macro-level boundary conditions on the effect of state ownership on trade credit. The dependent variable is 100 times the ratio of trade receivables to total sales. Trade receivables equals amounts on open account (net of applicable reserves) owed by customers for goods and services sold in the ordinary course of business. We lag all independent variables by one year. The “Appendix” provides variable definitions and sources. The full sample contains 5503 firm-year observations from 574 firms privatized in 64 countries. We winsorize all financial variables at the 1% level in both tails of the distribution. Regressions include country dummy variables, industry dummy variables (based on 48 industry groupings in Fama & French, 1997), and year dummy variables. Robust standard errors in parentheses below each coefficient are clustered at the firm level.